Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Buteo

View on Wikipedia

| Buteo Temporal range: Oligocene – present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Common buzzard (Buteo buteo) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Subfamily: | Buteoninae |

| Genus: | Buteo Lacépède, 1799 |

| Type species | |

| Falco buteo Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Species | |

|

About 30, see text | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Asturina | |

Buteo is a genus of medium to fairly large, wide-ranging raptors with a robust body and broad wings. In the Old World, members of this genus are called "buzzards", but "hawk" is used in the New World (Etymology: Buteo is the Latin name of the common buzzard[1]). As both terms are ambiguous, buteo is sometimes used instead, for example, by the Peregrine Fund.[2]

Characteristics

[edit]Buteos are fairly large birds. Total length can vary from 30 to 75 cm (12 to 30 in) and wingspan can range from 67 to 170 cm (26 to 67 in). The lightest known species is the roadside hawk,[a] at an average of 269 g (9.5 oz) although the lesser known white-rumped and Ridgway's hawks are similarly small in average wingspan around 75 cm (30 in), and average length around 35 cm (14 in) in standard measurements. The largest species in length and wingspan is the upland buzzard, which averages around 65 cm (26 in) in length and 152 cm (60 in) in wingspan. The upland is rivaled in weight and outsized in foot measurements and bill size by the ferruginous hawk. In both of these largest buteos, adults typically weigh over 1,200 g (2.6 lb), and in mature females, can exceed a mass of 2,000 g (4.4 lb).[5][6][7][8] All buteos may be noted for their broad wings and sturdy builds. They frequently soar on thermals at midday over openings and are most frequently seen while doing this. The flight style varies based on the body type and wing shape and surface size. Some long-winged species, such as rough-legged buzzards and Swainson's hawks, have a floppy, buoyant flight style, while others, such as red-tailed hawks and rufous-tailed hawks, tend to be relatively shorter-winged, soaring more slowly and flying with more labored, deeper flaps.[5] Most small and some medium-sized species, such as, red-shouldered hawk, often fly with an alternation of soaring and flapping, thus may be reminiscent of an Accipiter hawk in flight, but are still relatively larger-winged, shorter-tailed, and soar more extensively in open areas than Accipiter species do.[5][9] Buteos inhabit a wide range of habitats across the world, but tend to prefer some access to both clearings, which provide ideal hunting grounds, and trees, which can provide nesting locations and security.[6][7]

Diet

[edit]All Buteo species are to some extent opportunistic when it comes to hunting, and prey on almost any type of small animal as it becomes available to them. However, most have a strong preference for small mammals, mostly rodents. Rodents of almost every family in the world are somewhere preyed upon by Buteo species.[5][6][7] Since many rodents are primarily nocturnal, most buteos mainly hunt rodents that may be partially active during the day, which can include squirrels and chipmunks, voles, and gerbils. More nocturnal varieties are hunted opportunistically and may be caught in the first or last few hours of light.[5][7] Other smallish mammals, such as shrews, moles, pikas, bats, and weasels, tend to be minor secondary prey, although can locally be significant for individual species.[5][7] Larger mammals, such as rabbits, hares, and marmots, including even adult specimens weighing as much as 2 to 3 kg (4.4 to 6.6 lb), may be hunted by the heaviest and strongest species, such as ferruginous,[7][10][11] red-tailed[12] and white-tailed hawks.[13] Birds are taken occasionally, as well. Small to mid-sized birds, i.e. passerines, woodpeckers, waterfowl, pigeons, and gamebirds, are most often taken. However, since the adults of most smaller birds can successfully outmaneuver and evade buteos in flight, much avian prey is taken in the nestling or fledgling stages or adult birds if they are previously injured.[5][7] An exception is the short-tailed hawk, which is a relatively small and agile species and is locally a small bird-hunting specialist.[14] The Hawaiian hawk, which evolved on an isolated group of islands with no terrestrial mammals, was also initially a bird specialist, although today it preys mainly on introduced rodents. Other prey may include snakes, lizards, frogs, salamanders, fish, and even various invertebrates, especially beetles. In several Buteo species found in more tropical regions, such as the grey-lined hawk, reptiles and amphibians may come to locally dominate the diet.[5] Swainson's hawk, despite its somewhat large size, is something of exceptional insect-feeding specialist and may rely almost fully on crickets and dragonflies when wintering in southern South America.[15][16] Carrion is eaten occasionally by most species, but is almost always secondary to live prey.[5] The importance of carrion in the Old World "buzzard" species is relatively higher since these often seem slower and less active predators than their equivalents in the Americas.[17][18][19] Most Buteo species seem to prefer to ambush prey by pouncing down to the ground directly from a perch. In a secondary approach, many spot prey from a great distance while soaring and circle down to the ground to snatch it.[5]

Reproduction

[edit]Buteos are typical accipitrids in most of their breeding behaviors. They all build their own nests, which are often constructed out of sticks and other materials they can carry. Nests are generally located in trees, which are generally selected based on large sizes and inaccessibility to climbing predators rather than by species. Most Buteos breed in stable pairs, which may mate for life or at least for several years even in migratory species in which pairs part ways during winter. Generally from 2 to 4 eggs are laid by the female and are mostly incubated by her, while the male mate provides food. Once the eggs hatch, the survival of the young is dependent upon how abundant appropriate food is and the security of the nesting location from potential nest predators and other (often human-induced) disturbances. As in many raptors, the nestlings hatch at intervals of a day or two and the older, strong siblings tend to have the best chances of survival, with the younger siblings often starving or being handled aggressively (and even killed) by their older siblings. The male generally does most of the hunting and the female broods, but the male may also do some brooding while the female hunts as well. Once the fledgling stage is reached, the female takes over much of the hunting. After a stage averaging a couple of weeks, the fledglings take the adults' increasing indifference to feeding them or occasional hostile behavior towards them as a cue to disperse on their own. Generally, young Buteos tend to disperse several miles away from their nesting grounds and wander for one to two years until they can court a mate and establish their own breeding range.[5][6][7]

Distribution

[edit]The Buteo hawks include many of the most widely distributed, most common, and best-known raptors in the world. Examples include the red-tailed hawk of North America and the common buzzard of Eurasia. Most Northern Hemisphere species are at least partially migratory. In North America, species such as broad-winged hawks and Swainson's hawks are known for their huge numbers (often called "kettles") while passing over major migratory flyways in the fall. Up to tens of thousands of these Buteos can be seen each day during the peak of their migration. Any of the prior mentioned common Buteo species may have total populations that exceed a million individuals.[5] On the other hand, the Socotra buzzard and Galapagos hawks are considered vulnerable to extinction per the IUCN. The Ridgway's hawk is even more direly threatened and is considered Critically Endangered. These insular forms are threatened primarily by habitat destruction, prey reductions and poisoning.[5][6] The latter reason is considered the main cause of a noted decline in the population of the more abundant Swainson's hawk, due to insecticides being used in southern South America, which the hawks ingest through crickets and then die from poisoning.[20]

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]The genus Buteo was erected by the French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède in 1799 by tautonymy with the specific name of the common buzzard Falco buteo which had been introduced by Carl Linnaeus in 1758.[21][22]

Extant species in taxonomic order

[edit]| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common buzzard | Buteo buteo (Linnaeus, 1758) Six subspecies

|

northwestern China (Tian Shan), far western Siberia and northwestern Mongolia.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Eastern buzzard | Buteo japonicus (Temminck & Schlegel, 1844) Four subspecies

|

East Asia and some parts of Russia and South Asi

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Himalayan buzzard | Buteo refectus Portenko, 1935 |

the Himalayas in Nepal, India and southern China.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Cape Verde buzzard

|

Buteo bannermani (Swann, 1919) |

Cape Verde

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

|

| Socotra buzzard | Buteo socotraensis Porter & Kirwan, 2010 |

Socotra, Yemen

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

VU |

| Red-tailed hawk | Buteo jamaicensis (Gmelin, 1788) Fourteen subspecies

|

Alaska and northern Canada to as far south as Panama and the West Indies.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Long-legged buzzard | Buteo rufinus (Cretzschmar, 1829) Two subspecies

|

Southeastern Europe down to East Africa to the northern part of the Indian subcontinent.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Rough-legged buzzard | Buteo lagopus (Pontoppidan, 1763) Four subspecies

|

Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America, Europe, and Russia

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Ferruginous hawk | Buteo regalis (Gray, 1844) |

North America

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Red-shouldered hawk | Buteo lineatus (Gmelin, 1788) |

eastern North America and along the coast of California and northern to northeastern-central Mexico.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Broad-winged hawk | Buteo platypterus (Vieillot, 1823) Six subspecies

|

eastern North America, as far west as British Columbia and Texas, Neotropics from Mexico south to southern Brazil

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Swainson's hawk | Buteo swainsoni Bonaparte, 1838 |

western North America, Chile, Argentina, Dominican Republic, and Trinidad and Tobago, and in Norway.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Ridgway's hawk | Buteo ridgwayi (Cory, 1883) |

Hispaniola

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

CR |

| Short-tailed hawk | Buteo brachyurus (Vieillot, 1816) Two subspecies

|

From southeastern Brazil and northern Argentina north through Central America to the mountains of the Mexico-Arizona border area, as well as in southern Florida, United States

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| White-throated hawk | Buteo albigula Philippi, 1899 |

South America

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Galapagos hawk | Buteo galapagoensis (Gould, 1837) |

Galápagos Islands

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

VU |

| Gray-lined hawk | Buteo nitidus Latham, 1790 Three subspecies

|

El Salvador to Argentina, as well as on the Caribbean island of Trinidad.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Gray hawk | Buteo plagiatus (Schlegel, 1862) |

from Costa Rica north into the southwestern United States

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Zone-tailed hawk | Buteo albonotatus (Kaup, 1847) |

southern Arizona, New Mexico, and western Texas almost throughout inland Mexico and the central portions of Central America down into eastern Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, southern Brazil, Paraguay, Bolivia, and northern Argentina.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Hawaiian hawk | Buteo solitarius (Peale, 1848) |

Hawaii | Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NT |

| Rufous-tailed hawk | Buteo ventralis Gould, 1837 |

Argentina, Chile

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

VU |

| Mountain buzzard | Buteo oreophilus Hartert and Neumann, 1914 |

East Africa | Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NT |

| Forest buzzard | Buteo trizonatus Rudebeck, 1957 |

South Africa, Lesotho and Eswatini | Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NT |

| Madagascar buzzard | Buteo brachypterus Hartlaub, 1860 |

Madagascar

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Upland buzzard | Buteo hemilasius Temminck & Schlegel, 1844 |

Central and East Asia | Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Red-necked buzzard | Buteo auguralis Salvadori, 1865 |

The Sahel and Central Africa | Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Jackal buzzard | Buteo rufofuscus (Forster, 1798) |

Southern Africa | Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC |

| Augur buzzard | Buteo augur (Rüppell, 1836) Two subspecies

|

from Ethiopia to southern Angola and central Namibia.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC

|

Fossil record

[edit]A number of fossil species have been discovered, mainly in North America. Some are placed here primarily based on considerations of biogeography, Buteo being somewhat hard to distinguish from Geranoaetus based on osteology alone:[51]

- †Buteo dondasi (Late Pliocene of Buenos Aires, Argentina)

- †Buteo fluviaticus (Brule Middle? Oligocene of Wealt County, US) – possibly same as B. grangeri

- †Buteo grangeri (Brule Middle? Oligocene of Washabaugh County, South Dakota, US)

- †Buteo antecursor (Brule Late? Oligocene)

- †?Buteo sp. (Brule Late Oligocene of Washington County, US)[52]

- †Buteo ales (Agate Fossil Beds Early Miocene of Sioux County, US) – formerly in Geranospiza or Geranoaetus

- †Buteo typhoius (Olcott Early ?- snake Creek Late Miocene of Sioux County, US)

- †Buteo pusillus (Middle Miocene of Grive-Saint-Alban, France)

- †Buteo sp. (Middle Miocene of Grive-Saint-Alban, France – Early Pleistocene of Bacton, England)[53]

- †Buteo contortus (snake Creek Late Miocene of Sioux County, US) – formerly in Geranoaetus

- †Buteo spassovi (Late Miocene of Chadžidimovo, Bulgaria)[54]

- †Buteo conterminus (snake Creek Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Sioux County, US) – formerly in Geranoaetus

- †Buteo sp. (Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina, US)

- †Buteo sanya (Late Pleistocene of Luobidang Cave, Hainan, China)

- †Buteo chimborazoensis (Late Pleistocene of Ecuador)[55]

- †Buteo sanfelipensis (Late Pleistocene, Cuba)

An unidentifiable accipitrid that occurred on Ibiza in the Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene may also have been a Buteo.[57] If this is so, the bird can be expected to aid in untangling the complicated evolutionary history of the common buzzard group.

The prehistoric species "Aquila" danana, Buteogallus fragilis (Fragile eagle), and Spizaetus grinnelli were at one time also placed in Buteo.[51]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 81. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Buteos at the Peregrine Fund". peregrinefund.org. Archived from the original on 2007-02-12.

- ^ Kaup, Johann Jakob (1844). Classification der Säugethiere und Vögel (in German). Darmstadt: Carl Wilhelm Leske. p. 120. Retrieved 28 December 2022 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2022). "Hoatzin, New World vultures, Secretarybird, raptors". IOC World Bird List Version 12.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D. (2001). Raptors of the World. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-8026-1.

- ^ a b c d e del Hoyo, J.; Elliot, A. & Sargatal, J. (editors). (1994). Handbook of the Birds of the World Volume 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-15-6

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World by Leslie Brown & Dean Amadon. The Wellfleet Press (1986), ISBN 978-1555214722.

- ^ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ Crossley, R., Liguori, J. & Sullivan, B. The Crossley ID Guide: Raptors. Princeton University Press (2013), ISBN 978-0691157405.

- ^ Smith, D. G. and J. R. Murphy. 1978. Biology of the Ferruginous Hawk in central Utah. Sociobiology 3:79-98.

- ^ Thurow, T. L., C. M. White, R. P. Howard, and J. F. Sullivan. 1980. Raptor ecology of Raft River valley, Idaho. EG&G Idaho, Inc. Idaho Falls.

- ^ Smith, D. G. and J. R. Murphy. 1973. Breeding ecology of raptors in the East Great Basin Desert of Utah. Brigham Young Univ. Sci. Bull., Biol. Ser. Vol. 18:1-76.

- ^ Kopeny, M. T. 1988a. White-tailed Hawk. Pages 97–104 in Southwest raptor management symposium and workshop. (Glinski, R. L. and et al., Eds.) Natl. Wildl. Fed. Washington, D.C.

- ^ Ogden, J. C. 1974. The Short-tailed Hawk in Florida. I. Migration, habitat, hunting techniques, and food habits. Auk 91:95-110.

- ^ Snyder, N. F. R. and J. W. Wiley. 1976. Sexual size dimorphism in hawks and owls of North America. Ornithol. Monogr. no. 20.

- ^ Jaramillo, A. P. 1993. Wintering Swainson's Hawks in Argentina: food and age segregation. Condor 95:475-479.

- ^ Tubbs, C.R. 1974. The buzzard. David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

- ^ Wu, Y.-Q., M. Ma, F. Xu, D. Ragyov, J. Shergalin, N.F. Lie, and A. Dixon. 2008. Breeding biology and diet of the Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufius) in the eastern Junggar Basin of northwestern China. Journal of Raptor Research 42:273-280.

- ^ Allan, D.G. 2005. Jackal Buzzard Buteo rufofuscus. P.A.R. Hockey, W.R.J. Dean, and P.G. Ryan (eds.). Pp. 526–527 in Roberts Birds of Southern Africa. VIIth ed. Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, South Africa.

- ^ Weidensaul, S. Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere With Migratory Birds. North Point Press (2000), ISBN 978-0865475915.

- ^ Lacépède, Bernard Germain de (1799). "Tableau des sous-classes, divisions, sous-division, ordres et genres des oiseux". Discours d'ouverture et de clôture du cours d'histoire naturelle (in French). Paris: Plassan. p. 4. Page numbering starts at one for each of the three sections.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 361.

- ^ Ferguson-Lees, J., & Christie, D. A. (2001). Raptors of the world. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Buteo buteo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T61695117A206634667. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T61695117A206634667.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Buteo japonicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T22732232A200958179. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22732232A200958179.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo refectus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22734099A95074452. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22734099A95074452.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2022). "Buteo socotraensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022 e.T22732235A216969152. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T22732235A216969152.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo jamaicensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22695933A93534834. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695933A93534834.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Buteo rufinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T22736562A202674118. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22736562A202674118.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Buteo lagopus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T22695973A202640529. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22695973A202640529.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo regalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22695970A93535999. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695970A93535999.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo lineatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22695883A93531542. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695883A93531542.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo platypterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22695891A93532112. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695891A93532112.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo swainsoni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22695903A93533217. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695903A93533217.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2020). "Buteo ridgwayi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T22695886A181707428. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22695886A181707428.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2020). "Buteo brachyurus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T22695897A169004381. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22695897A169004381.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Buteo albigula". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018 e.T22695900A131937573. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22695900A131937573.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Buteo galapagoensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T22695909A194428673. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22695909A194428673.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2020). "Buteo nitidus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T22727766A168803943. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22727766A168803943.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2020). "Buteo plagiatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T22727773A169002997. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22727773A169002997.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2020). "Buteo albonotatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T22695926A169006783. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22695926A169006783.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2023). "Buteo solitarius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2023 e.T22695929A225199006. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T22695929A225199006.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo ventralis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22695936A93535276. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695936A93535276.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2022). "Buteo oreophilus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022 e.T22728020A212860714. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T22728020A212860714.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Buteo trizonatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T22735392A206649395. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22735392A206649395.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo brachypterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22695957A93535514. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695957A93535514.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Buteo hemilasius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T22695967A202604414. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22695967A202604414.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Buteo auguralis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021 e.T22695978A202595837. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22695978A202595837.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo rufofuscus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22695987A93537350. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695987A93537350.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo augur". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22732019A95040751. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22732019A95040751.en. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ a b Wetmore (1933)

- ^ A complete left ulna similar to Buteo but of distinctly small size: Cracraft (1969)

- ^ Probably several species; similar to Common Buzzard in appearance and size: Ballmann (1969), Mlíkovský (2002)

- ^ Boev, Z., D. Kovachev. 1998. Buteo spassovi sp. n. - a Late Miocene Buzzard (Accipitridae, Aves) from SW Bulgaria. - Geologica Balcanica, 29 (1-2): 125–129.

- ^ Lo Coco, Gastón E.; Agnolín, Federico L.; Román Carrión, José Luis (2024-10-29). "New records of Pleistocene birds of prey from Ecuador". Journal of Ornithology. 166 (2): 495–509. Bibcode:2025JOrni.166..495L. doi:10.1007/s10336-024-02229-1. ISSN 2193-7206.

- ^ Brodkorb (1962), Mlíkovský (2002)

- ^ Alcover (1989)

Further reading

[edit]- "Raptors of the World" by Ferguson-Lees, Christie, Franklin, Mead & Burton. Houghton Mifflin (2001), ISBN 0-618-12762-3.

- Alcover, Josep Antoni (1989): Les Aus fòssils de la Cova de Ca Na Reia. Endins 14-15: 95-100. [In Catalan with English abstract]

- Ballmann, Peter (1969): Les Oiseaux miocènes de la Grive-Saint-Alban (Isère) [The Miocene birds of Grive-Saint-Alban (Isère)]. Geobios 2: 157–204. [French with English abstract] doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(69)80005-7 (HTML abstract)

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1964): Catalogue of Fossil Birds: Part 2 (Anseriformes through Galliformes). Bulletin of the Florida State Museum 8(3): 195–335. PDF or JPEG fulltext Archived 2008-02-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Cracraft, Joel (1969): Notes on fossil hawks (Accipitridae). Auk 86(2): 353–354. PDF fulltext

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002): Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe. Ninox Press, Prague. ISBN 80-901105-3-8

{{isbn}}: ignored ISBN errors (link) PDF fulltext - Wetmore, Alexander (1933): Status of the Genus Geranoaëtus. Auk 50(2): 212. DjVu fulltext PDF fulltext

Buteo

View on GrokipediaDescription

Physical Characteristics

Buteo species are medium to large raptors characterized by robust body builds, broad rounded wings adapted for efficient soaring, short tails, and strong legs armed with sharp talons for capturing prey.[1] These features provide a foundational morphology that distinguishes the genus within the Accipitridae family, with overall sizes varying significantly across species to reflect diverse ecological roles. For example, the smallest members, such as the roadside hawk (Buteo magnirostris), measure 33–41 cm in length with wingspans of approximately 70 cm, while larger species like the upland buzzard (Buteo hemilasius) reach 57–72 cm in length and wingspans of 143–161 cm.[4][5] Plumage in Buteo is highly variable, often featuring polymorphic forms that include light and dark morphs, which aid in camouflage within their environments. The red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) exemplifies this with its adults displaying a characteristic reddish-brown tail, contrasting with the mottled brown upperparts and pale underparts barred with darker streaks seen in the common buzzard (Buteo buteo).[6][7] Sexual dimorphism is subtle in coloration but pronounced in size, with females typically 10–20% larger than males, a pattern common across the genus to support differing reproductive demands.[8] The head features a hooked bill covered at the base by a yellow cere, paired with large, forward-facing eyes that enable keen binocular vision for spotting prey from afar.[1] Internally, Buteo possess skeletal adaptations such as a keeled sternum, which anchors robust flight muscles essential for sustained aerial activity. Specific variations highlight the genus's diversity; the ferruginous hawk (Buteo regalis) attains lengths up to 61 cm and wingspans nearing 150 cm, showcasing a pale morph with rusty shoulders and white underparts, while the zone-tailed hawk (Buteo albonotatus) exhibits predominantly black plumage accented by two narrow white bands on the tail, superficially mimicking the turkey vulture.[9][10] These traits collectively underscore the morphological versatility that enables Buteo to exploit a wide array of habitats through soaring adaptations.[1]Flight and Behavior

Buteo species are renowned for their soaring flight, leveraging broad, rounded wings to efficiently glide on thermal updrafts with only intermittent flapping for adjustments. This adaptation allows them to cover vast distances while conserving energy, as the robust build and short tails of these hawks facilitate stable, high-aspect-ratio gliding.[11][12] They are capable of reaching altitudes up to 2,000 meters above ground level during flight, particularly in thermal-rich environments, enabling extended aerial patrols over open landscapes.[13] Territorial behaviors in Buteo often involve dramatic aerial displays, such as the sky-dancing performed by males of the red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus), where individuals soar to great heights before executing undulating dives, steep plunges followed by wide spirals, and rapid ascents to advertise territory or attract mates. Perch-hunting from elevated sites, including treetops, utility poles, or high ground, is a common strategy across the genus, allowing these hawks to scan for movement over wide areas before launching short, direct attacks.[14][15] Vocalizations play a key role in communication, featuring piercing screams or mewing calls; for instance, the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) emits a hoarse "kee-eeeee-arr" lasting 2-3 seconds, often while soaring, to signal alarm or during courtship interactions.[16] Most Buteo exhibit a solitary social structure or form loose breeding pairs during the season, maintaining individual territories with minimal group interaction outside of mating. Exceptions include the Swainson's hawk (Buteo swainsoni), which demonstrates more social tendencies by aggregating into large migratory kettles comprising thousands of individuals that spiral upward on thermals. These hawks are strictly diurnal, with activity patterns spanning daylight hours and peaks often around midday when thermals are strongest, though some foraging may intensify at dawn or dusk in varied habitats. In the wild, Buteo typically achieve longevity of 10-20 years, influenced by predation, disease, and resource availability, while individuals in captivity can survive up to 30 years under protected conditions.[17][18][8]Ecology

Diet and Foraging

Buteo species are opportunistic carnivores whose diets consist primarily of small to medium-sized mammals, with rodents such as voles and mice forming a major component, often comprising 60–85% of prey occurrences in many populations.[19][20] Rabbits and hares can constitute up to 50% of the diet in grassland habitats for species like the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), while diets are supplemented by birds (up to 26% in the broad-winged hawk, Buteo platypterus), reptiles, amphibians, insects, and occasionally carrion.[21][22] Foraging strategies in Buteo emphasize energy-efficient ambush tactics, including perch hunting from elevated sites like trees or poles, where individuals scan for movement before stooping on prey at speeds up to 190 km/h (120 mph).[23] Low-level soaring over open ground allows for visual searches, and some species, such as the Swainson's hawk (Buteo swainsoni), engage in communal foraging in flocks of up to thousands, coordinating to exploit insect swarms or disturbed fields without true cooperative pursuit.[24] Their gape morphology enables swallowing smaller prey whole or tearing larger items into pieces with the bill and talons.[25] Dietary composition varies seasonally, particularly in northern species; for instance, the rough-legged hawk (Buteo lagopus) relies heavily on lemmings during arctic breeding seasons, where they can account for 80–85% of intake, shifting to similar microtine rodents in winter ranges.[26][27] Digestive adaptations support these habits, including a crop for temporary prey storage to allow intermittent feeding and uric acid excretion in feces, which conserves water in arid or cold environments.[28][29] As mid-level to apex predators, Buteo hawks regulate rodent populations in ecosystems, with species like the red-tailed hawk consuming an average of 135–145 g of prey daily, primarily small mammals, thereby aiding pest control in agricultural areas.[21][30]Reproduction and Life Cycle

Buteo species typically form monogamous pairs that defend territories either year-round or seasonally, depending on the species and local conditions.[1] Courtship rituals often include aerial chases and food passes between mates, reinforcing pair bonds and territorial claims.[31] Nests are constructed in trees or on cliffs using sticks and twigs, with the interior lined with softer materials such as bark, moss, or fresh greenery; these structures are frequently reused and refurbished annually by the same pair.[15][32] Clutch sizes generally range from 2 to 4 eggs, which are white or pale blue with reddish-brown spots or blotches.[33] Incubation lasts 28 to 35 days and is primarily performed by the female, who is fed by the male during this period; hatching is asynchronous, with eggs hatching 1 to 3 days apart.[34][35] This asynchrony can lead to siblicide, where stronger, earlier-hatching nestlings attack and sometimes kill weaker siblings, particularly in years of low prey abundance when food is limited.[36] Nestlings emerge covered in downy gray or white plumage for initial thermoregulation and camouflage within the nest.[37] They are brooded by the female for the first 2 to 3 weeks while the male provides most food, transitioning to self-feeding as feathers develop. Fledging occurs at 35 to 60 days post-hatching, varying by species and environmental factors; juveniles remain dependent on parents for 1 to 3 months after fledging, during which they learn hunting skills through observation and practice.[38][39] Juvenile plumage is mottled brown and buff for effective camouflage in varied habitats, aiding survival during this vulnerable phase.[7] Dispersal typically follows, with young traveling 100 to 500 km from natal sites to establish independence.[40] Sexual maturity is reached at 2 to 3 years of age, after which individuals may begin breeding.[41] Annual breeding success varies from 50% to 70%, strongly influenced by prey abundance, with higher rates in areas of plentiful small mammals or birds that support larger broods.[42] While most Buteo exhibit biparental care, some species like the Galápagos hawk (B. galapagoensis) demonstrate cooperative breeding, where groups including multiple males act as helpers to assist in territory defense and chick rearing.[43]Distribution and Habitat

Geographic Range

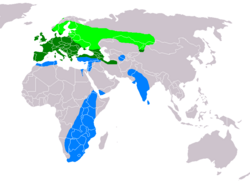

The genus Buteo exhibits a broad near-cosmopolitan distribution across the Americas, Eurasia, and Africa, encompassing diverse continental regions but notably absent from Australia, Antarctica, polar areas, and most oceanic islands.[1] Species occupy latitudes from the Arctic Circle southward to the tropics, with representatives in open woodlands, grasslands, and savannas throughout these continents, though they are generally excluded from dense, unbroken rainforests.[44] For instance, the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) is one of the most widespread, breeding from Alaska and northern Canada across much of North America to Panama and the northern edges of South America.[45] Migration plays a key role in the distribution of many Buteo species, with at least 10 exhibiting partial or complete migratory patterns driven by seasonal prey availability and weather.[46] The broad-winged hawk (Buteo platypterus), for example, is an obligate long-distance migrant, traveling approximately 7,000 km from breeding forests in eastern North America to wintering grounds in northern South America, often forming massive kettles of thousands of individuals during passage through Central America.[47] In contrast, tropical residents like the gray hawk (Buteo plagiatus) remain year-round in their range from southwestern United States through Mexico, Central America, and into northern South America as far as northern Argentina.[48] Historical range expansions, particularly following the last glacial maximum, have shaped northern distributions for several species. Phylogeographic studies indicate post-glacial recolonization of higher latitudes, with limited genetic differentiation suggesting rapid expansion; for example, the Swainson's hawk (Buteo swainsoni) shows no significant structure across its North American breeding range, consistent with recent northward spread.[49] Island endemism is rare but notable, as seen in the Hawaiian hawk (Buteo solitarius), which is confined to the Big Island of Hawai'i.[50] Overlap zones occur where closely related taxa meet, such as in Eurasia, where the common buzzard (Buteo buteo) subspecies—including the nominate buteo in western Europe and vulpinus (steppe buzzard) in central Asia—co-occur in eastern Europe and western Asia, facilitating gene flow between forms.Preferred Habitats

Species of the genus Buteo generally prefer open to semi-open habitats that provide ample perching opportunities for hunting and nesting sites, such as open woodlands, grasslands, savannas, and deserts with scattered trees or elevated structures.[1] They typically avoid dense, unbroken forests but frequently utilize forest edges where visibility and access to prey are enhanced.[51] These raptors occupy a broad elevational range, from sea level to over 4,000 m, adapting to varied topographies that support their soaring flight style.[52] Adaptations to specific environments are evident across the genus; for instance, the long-legged buzzard (Buteo rufinus) thrives in arid steppes and semi-deserts of the Middle East and Central Asia, where its long legs facilitate ground-level hunting in open, dry plains up to 3,500 m.[52] In contrast, the forest buzzard (Buteo trizonatus) is specialized for African woodlands, favoring native temperate forests and edges from sea level to 1,500 m, though it also occupies adjacent open areas for foraging.[53] The rough-legged hawk (Buteo lagopus) exemplifies tolerance for extreme climates, breeding in arctic tundra and subarctic open country during summer.[54] Microhabitat requirements include proximity to water sources for bathing and drinking, as well as varied terrain that generates thermal updrafts essential for efficient soaring and energy conservation during flight.[1] These features allow Buteo species to exploit diverse prey in expansive areas without excessive energy expenditure.[15] Many Buteo species demonstrate increasing use of human-modified landscapes, such as farmlands and urban edges, where artificial perches like utility poles and streetlights substitute for natural trees; the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), for example, readily nests in suburban and urban settings with suitable open hunting grounds.[55] However, habitat fragmentation from agricultural intensification can limit population viability by reducing connectivity between foraging and nesting sites.[56]Taxonomy and Systematics

Etymology and Classification History

The genus Buteo derives its name from the Latin buteo, referring to a type of hawk or falcon, particularly the common buzzard.[57] This name was established in 1799 by the French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède through tautonymy with the specific epithet of the common buzzard (Falco buteo), though the genus encompassed New World species from its inception, reflecting early recognition of their morphological similarities to Old World buzzards.[57] Initially classified within the broader order Falconiformes, which included diverse raptors, Buteo was formally placed in the family Accipitridae by Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1816, distinguishing it from the more agile Falconidae based on soaring flight and robust build.[58] Phylogenetic studies in the 2000s, utilizing mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences, confirmed the monophyly of Buteo within the subfamily Buteoninae of Accipitridae, with the genus forming a clade sister to Parabuteo, supporting its evolutionary cohesion among broad-winged hawks adapted to open habitats.[59] Earlier molecular analyses had suggested paraphyly due to divergent lineages like the roadside hawk, but subsequent revisions resolved this by elevating such taxa to separate genera, preserving Buteo's integrity.[60] Key taxonomic adjustments in the 2010s included the 2017 split of the roadside hawk from Buteo magnirostris to the monotypic genus Rupornis magnirostris, based on genetic divergence and morphological distinctions, as proposed by the South American Classification Committee.[61] Updates from authoritative checklists, such as eBird and the IOC World Bird List version 15.1 (February 2025), maintain 28 species in Buteo, with no major splits or lumps post-2023 beyond minor sequence reordering within species complexes like the common buzzard group.[62][63] These refinements underscore ongoing refinements in avian systematics driven by integrative taxonomy. The genus traces its origins to early accipitrids, with a major radiation during the Miocene epoch (approximately 23–5 million years ago), coinciding with the global expansion of C4 grasslands that favored soaring predators exploiting open landscapes for thermaling and prey detection.[64] Tentative Buteo-like fossils from the Oligocene exist, but the oldest confirmed Buteo fossils are from the Late Miocene of Italy, indicating a Neotropical cradle followed by dispersal.[65]Extant Species

The genus Buteo includes 28 extant species recognized by the International Ornithologists' Union (IOC) World Bird List version 15.1 (February 2025), divided into Old World buzzards and New World hawks, with taxonomic order reflecting phylogenetic relationships based on molecular and morphological data.[66] These species exhibit diverse plumage variations and adaptations, but all share broad wings suited for soaring. Hybrids occur in regions of sympatry, such as between B. jamaicensis and B. lineatus in North America.[67] No new species have been described in the genus between 2023 and 2025.[67] The following table lists all extant Buteo species in taxonomic order, with brief descriptions of unique traits, primary distribution, IUCN Red List status (as of 2025 assessments), and population estimates where available from authoritative sources.[68]| Scientific Name | Common Name | Unique Traits | Primary Distribution | IUCN Status (2025) | Population Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buteo bannermani | Cape Verde Buzzard | Dark morph predominant, isolated island form with limited variation | Cape Verde Islands (Africa) | LC | Not quantified; stable small population |

| Buteo buteo | Common Buzzard | Highly variable plumage (rufous, grey, or white forms), adaptable generalist | Eurasia, North Africa | LC | >1 million mature individuals globally |

| Buteo refectus | Himalayan Buzzard | Pale underparts, shorter tail than close relatives, high-altitude specialist | Central Asia (Himalayas) | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo hemilasius | Upland Buzzard | Large size, pale head and underwing coverts, nomadic in steppes | Central and East Asia | LC | Stable, widespread |

| Buteo japonicus | Eastern Buzzard | Dark morph common, distinct vocalizations from western congeners | East Asia, Japan | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo rufinus | Long-legged Buzzard | Long legs and tail, pale morph with dark carpal patches, arid habitat specialist | Eurasia, Middle East, North Africa | LC | Not quantified; stable |

| Buteo brachypterus | Madagascar Buzzard | Short wings relative to body, vocal mimicry of other raptors | Madagascar | NT | ~1,000 mature individuals; declining due to habitat loss |

| Buteo auguralis | Red-necked Buzzard | Chestnut nape and collar, perches conspicuously in savannas | Sub-Saharan Africa | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo augur | Augur Buzzard | Bicolored plumage (black upperparts, white underparts with black carpal patches) | Sub-Saharan Africa | LC | Stable |

| Buteo rufofuscus | Jackal Buzzard | Rufous tail and shoulders, often hovers while hunting | Southern Africa | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo oreophilus | Mountain Buzzard | Small size, spotted breast, forest-edge dweller | East Africa | LC | Small but stable |

| Buteo trizonatus | Forest Buzzard | Three dark breast bands, secretive in woodlands | Southern Africa | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo socotraensis | Socotra Buzzard | Pale morph dominant, endemic to arid islands | Socotra Archipelago (Yemen) | VU | <1,000 mature individuals; restricted range |

| Buteo nitidus | Grey-lined Hawk | Slender build, fine barring on flight feathers, canopy hunter | Central and South America | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo ridgwayi | Ridgway's Hawk | Dark hood, long tail, island specialist | Hispaniola (Caribbean) | CR | <400 mature individuals; increasing due to conservation as of 2025 |

| Buteo leucorrhous | White-rumped Hawk | White rump and underwing, tropical forest dweller | Central and South America | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo ventralis | Rufous-tailed Hawk | Bright rufous tail, white underparts with dark streaks | South America (Andes) | EN | <2,500 mature individuals; declining per 2025 update |

| Buteo albigula | White-throated Hawk | White throat and supercilium, montane forest form | Andes (South America) | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo polyosoma | Red-backed Hawk | Reddish back, variable morphs, high-elevation specialist | Andes (South America) | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo schistaceus | Variable Hawk | Highly polymorphic (dark, pale, intermediate), agile in mountains | Andes (South America) | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo poecilochrous | Puna Hawk | Spotted underparts, short tail, puna grassland adapter | Andes (South America) | LC | Not quantified |

| Buteo albonotatus | Zone-tailed Hawk | Black plumage with white wing bands mimicking turkey vultures for hunting advantage | Southwestern North America, South America | LC | Stable |

| Buteo lineatus | Red-shouldered Hawk | Rufous shoulder patches, banded tail, wetland preference | North and Central America | LC | >100,000 mature individuals |

| Buteo platypterus | Broad-winged Hawk | Compact body, broad wings for migration, flocks in thousands during fall | North and Central America | LC | Not quantified; migratory |

| Buteo brachyurus | Short-tailed Hawk | Two morphs (dark and light), short tail, soars high | Central and South America | LC | Stable |

| Buteo swainsoni | Swainson's Hawk | Long pointed wings, gregarious migrant, follows insect swarms | North and South America | LC | >100,000 mature individuals |

| Buteo jamaicensis | Red-tailed Hawk | Brick-red tail in adults, variable subspecies, urban adapter | North, Central, and South America | LC | >1 million mature individuals |

| Buteo regalis | Ferruginous Hawk | Pale morph with rusty legs and shoulders, grassland specialist | North America | NT | ~10,000-20,000 mature individuals; fluctuating |

| Buteo lagopus | Rough-legged Hawk | Feathered legs for cold climates, white tail with dark terminal band | Arctic North America, Eurasia | LC | Not quantified; migratory |

| Buteo solitarius | Hawaiian Hawk | Dark morph common, vocal during breeding, island endemic | Hawaii (USA) | NT | ~1,500-2,400 mature individuals; stable |

| Buteo galapagoensis | Galápagos Hawk | Variable morphs, inverted sexual size dimorphism, archipelago specialist | Galápagos Islands (Ecuador) | VU | ~500 mature individuals; inbreeding concerns |