Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cape Coloureds

View on Wikipedia

Cape Coloureds (Afrikaans: Kaapse Kleurlinge) are a South African group of Coloured people who are from the Cape region in South Africa which consists of the Western Cape, Northern Cape and the Eastern Cape. Their ancestry comes from the interracial mixing between the European, the indigenous Khoi and San, the Xhosa plus other Bantu people, indentured labourers imported from the British Raj, slaves imported from the Dutch East Indies, immigrants from the Levant or Yemen (or a combination of all).[3] Eventually, all these ethnic and racial groups intermixed with each other, forming a group of mixed-race people that became known as the "Cape Coloureds".

Key Information

Demographics

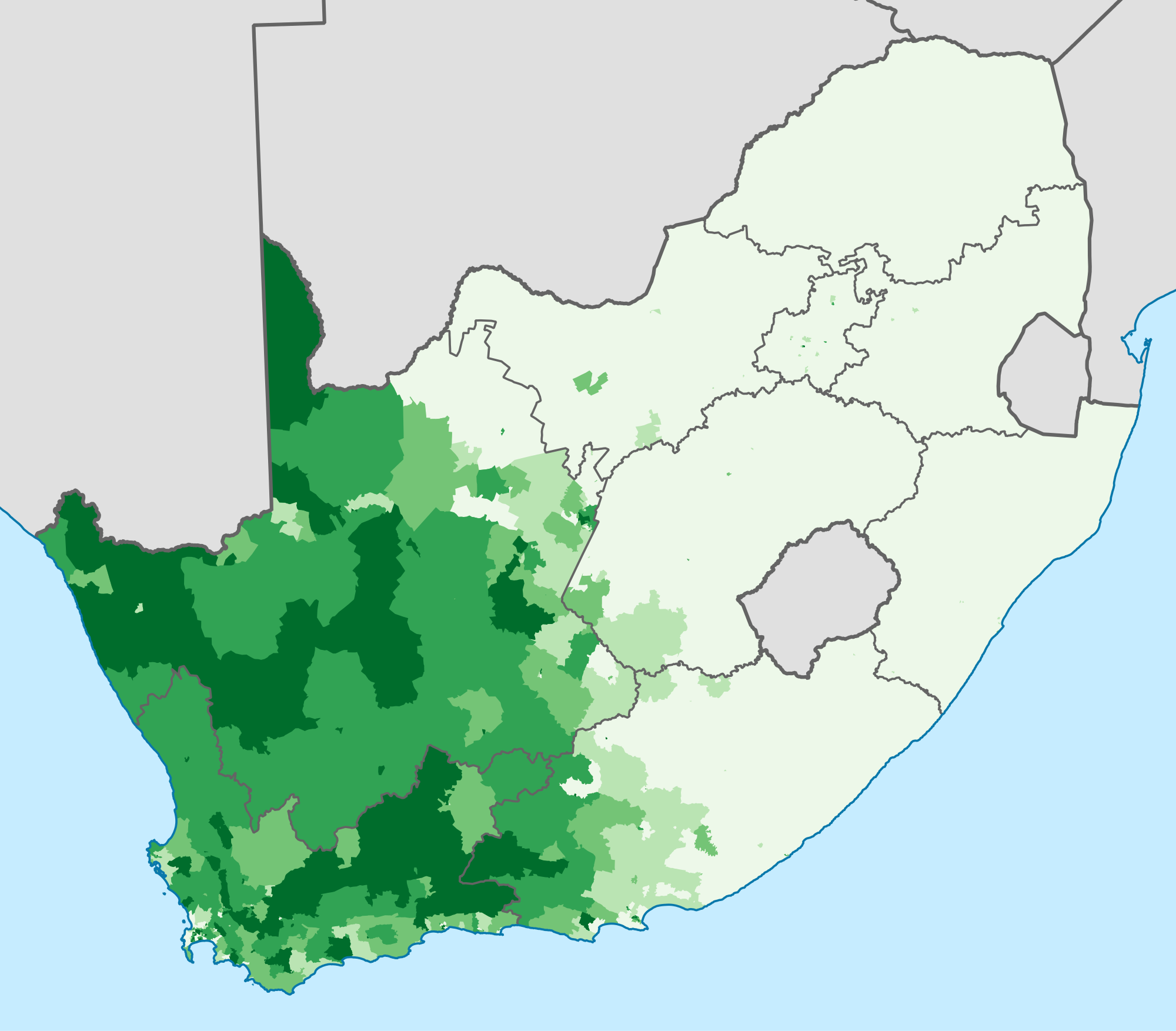

[edit]Although Coloureds represent only 8.15% of people within South Africa, they make up 42.1% of the population in the Western Cape, representing a plurality of the population of the province.[4] (according to the 2022 South African census)

They are generally bilingual, speaking Afrikaans and English, though some speak only one of these. Some Cape Coloureds may code switch,[5] speaking a patois of Afrikaans and English called Afrikaaps, also known as Cape Slang (Capy) or Kombuis Afrikaans, meaning Kitchen Afrikaans. Cape Coloureds were classified under apartheid as a subset of the larger Coloured race group.

Recent studies of Cape Coloureds using genetic testing have found ancestry to vary by region. Khoe-San ancestry is higher in inland regions and towards the north into the present-day Northern Cape.[7][8] Although it is prevalent throughout the Cape, the partial Bantu-speaking ancestry (most predominantly Xhosa) increases going eastwards into present-day Eastern Cape. The European-related ancestry is highest along the coast. In Cape Town and the rest of the Western Cape province, the partial Asian ancestry is high and diverse due to the arrival of Asian and African slaves that mixed with Europeans (colonists, immigrants, tourists) and existing mixed race (Khoisan-European) which formed the modern-day Cape Coloureds and Cape Malay due to the creolisation of all those populations.[9][10][11][12][13] At least 4 genetic studies indicate that the average Cape Coloured has an ancestry consisting of the following, with large variation between individuals:[14][15][7]

- Khoisan-speaking Africans: ~25.3%

- Bantu-speaking Africans: ~15.5%

- Ethnic groups in Europe: ~39.3%

- Asian peoples: ~19.9%

Below are the approximate ranges for each ancestral component based on genetic studies and historical accounts:[16]

- African Ancestry: Range: ~ 30-68%

- European Ancestry: Range: ~ 20-70%

- Asian Ancestry: Range: ~ 20-40%

- Middle Eastern Ancestry: Range: ~ 5-15%

Please note that this is not an exhaustive list, and individual results may vary. The ancestry of Cape Coloureds can be diverse and complex.

The genetic reference cluster term "Khoisan" itself refers to a colonially admixed population cluster, hence the concatenation, and is not a straightforward reference to ancient African pastoralist and hunter ancestry, which is often demarcated by the L0 haplogroup ancestry common in the general South African native population, which is also integral part of other aboriginal genetic reference cluster terms like "South-East African Bantu".[17]

Religion

[edit]A separate Dutch Reformed Church, the Dutch Reformed Mission Church (DRMC), was formed in 1881 to serve the Cape Coloured Calvinist population separately from the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa (NGK). It was merged in 1994 with the Dutch Reformed Church in Africa (DRCA, formed 1963) to form the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa.[citation needed]

Success in the spread of Catholicism among Afrikaans speakers, including Coloured communities, remained minimal until the death throes of Apartheid during the mid to late 1980s. As Catholic texts began to be translated into Afrikaans, sympathetic Dutch Reformed pastors, who were defying the traditional anti-Catholicism of their Church, assisted in correcting linguistic errors. By 1996, the majority of Afrikaans-speaking Catholics came from the Coloured community, with a smaller number of Afrikaner converts, most of whom were from professional backgrounds.[18]

Sunni Islam remains in practice among Cape Malays, who were generally regarded as a separate ethnoreligious group under apartheid.

Origin and history

[edit]The first and the largest phase of interracial marriages/miscegenation in South Africa happened in the Dutch Cape Colony and the rest of the Cape Colony which began from the 17th century, shortly after the arrival of Dutch settlers, who were led by Jan van Riebeeck, through the Dutch East India Company (also known as the 'VOC').[19] When the Dutch settled in the Cape in 1652, they met the Khoi Khoi who were the natives of the area.[20] After settling in the Cape, the Dutch established farms that required intensive labour, therefore, they enforced slavery in the Cape. Some of the Khoi Khoi became labourers for the Dutch farmers in the Cape. Despite this, there was resistance by the Khoi Khoi, which led to the Khoikhoi-Dutch Wars.[21]

As a result, the Dutch imported slaves from other parts of the world, especially the Malay people from present-day Indonesia and the Bantu people from various parts of Southern Africa.[22] Slaves were also imported from Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh (also known as 'Bengal'), Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Madagascar, Mauritius and the rest of Africa.[23][24] Because of this, the Cape had the most diverse slave population in the world.[25] The slaves were almost invariably given Christian names but their places of origin were indicated in the records of sales and other documents, so that it is possible to estimate the ratio of slaves from different regions.[26] Usually, slaves were given their masters' surnames, surnames that referred to the characters in the bible (e.g. Adams, Jephta, Thomas, Esau, Solomons, Jacobs, Matthews, Peters, Daniels), surnames that reflected the month when they arrived in the Cape (e.g. September, March/Maart, January/Januarie, April), surnames that referred to Greek and Roman mythology (e.g. Cupido, Adonis, Titus, Hannibal) or surnames that referred to the geographical location where they came from (e.g. 'Afrika' from different parts of mainland Africa, 'Balie' from Bali in Indonesia and 'Malgas' which referred to the Malagasy people from Madagascar).[27][28][29] These slaves were, however, dispersed and lost their cultural identity over the course of time.[30]

Even in the early years of colonialism, the area that became known as 'Cape Town', received international interest because it was the perfect halfway point for the trade route between Europe and Asia, which made Cape Town a vital trading station.[31] This is the main reason why the Cape was colonised by the Dutch so that the VOC could control and benefit from the Cape-Sea Route. This is also the main reason why the Dutch Cape Colony (especially in Cape Town) became a melting pot of people who came from different parts of the world and this melting pot still exists.[32] The majority of the early Europeans who settled in the Cape were men because they were mostly traders, sailors, soldiers, explorers, farmers and politicians who hardly brought their families with them; therefore, they created new families in the Cape.[33]

Because most of the Dutch settlers in the Cape were men, many of them married and fathered the first group of mixed-race children with the local Khoi Khoi women.[34] Soon after the arrival of slaves, the Dutch men also married and fathered mixed-race children with the Malay from Indonesia, the Southern African Bantu, Indians and other enslaved ethnic groups in the Cape.[35] To a certain extent, the slaves in the Cape also had interracial unions with each other and mixed-race children were also conceived from these unions as well because the slaves were of different races (African and Asian).[36] Some of these slaves also intermixed with the local Khoi Khoi workers and another breed of children were born with diverse heritage.[36] Unlike the One-drop rule in the US, the Dutch settlers in the Cape did not view mixed-race children as "white enough to be white", "black enough to be black" nor "Asian enough to be Asian", therefore, mixed race children from all these interracial unions in the Cape grew up, came together and married amongst themselves, forming their own creole community that would later be known as the "Cape Coloured" (a term that was given by the Apartheid regime during the 20th century).[37]

The first interracial marriage in the Cape was between Krotoa (a Khoi Khoi woman who was a servant, a translator and a crucial negotiator between the Dutch and the Khoi Khoi. Her Dutch name was "Eva Van Meerhof") and Peter Havgard (a Danish surgeon whom the Dutch renamed as "Pieter Van Meerhof").[38] Having conceived 3 mixed-race children, Krotoa was also known as the mother that gave birth to the Coloured community in South Africa.[39]

Eventually, more Dutch people settled in the Cape until the Cape fell under British rule in the early 19th century.[31] Amongst them were the Van Wijk family (whose descendants became 'Van Wyk') who arrived in the Cape in 1686 and the Erasmus family that arrived in 1689.[40][41][42] The arrival of more Dutch people in the Cape led to the recruitment of more Khoi Khoi labourers and the importation of more slaves from different parts of Asia and Africa.[43] From the mid-17th century until the 19th century and the 20th century, all the Dutch surnames in the Cape region and the rest of South Africa evolved into Afrikaans surnames which are the most common surnames amongst White South Africans and Coloured South Africans e.g. Van Niekerk, Strydom (from 'Strijdom'), De Waal, Pietersen, Van Rooyen, Van Tonder, Hanekom, Steenhuisen, De Jongh (from De Jong), Van Wyk, Van Der Walt, Van Der Merwe, Koekemoer, Meintjies, Beukes, Van Der Bijl, Uys, Oosthuizen, Theunissen, Pieterse, Willemse, Nieuwoudt.

The Huguenots (also known as 'French Huguenots') were French Protestants who escaped banishment and persecution of Protestants in France. Many of them emigrated to the Dutch Cape Colony to seek refuge among the existing Dutch community during the late 1600s and early 1700s.[44][45] Despite being refugees, they played a huge role on the history of the current Afrikaans-speaking community, the Cape region as a whole and the rest of South Africa. Coming from a country that has a rich history of wine production, these French refugees pioneered the vineyards of the Cape Winelands, turning it into one of the biggest wine producers in the world.[46][47] The town of Franschhoek (which means "French corner" in Dutch and Afrikaans) in the current Western Cape, was named as a refuge where many Huguenots were allocated by the VOC. Many Huguenots were also allocated to Stellenbosch, Paarl and the rest of the Cape Winelands because this was the perfect environment (in terms of climate and fertile land) for them to plant their vineyards and produce wine.[48]

Although many Huguenots, who arrived in the Cape, were already married, their children and descendants were soon absorbed into Cape society and after few generations, they spoke Dutch, not French.[49] Just like many White-Afrikaans speakers, many Coloured-Afrikaans speakers (especially those from the current Western Cape, Eastern Cape and the Northern Cape) also have some ancestry from France due to the Huguenots who integrated with the Dutch and other ethnic groups in the Cape region.[50] White-Afrikaans speakers and Coloured-Afrikaans speakers who specifically originate from the sub-region of the Cape Winelands (especially from the Franschhoek area, the Stellenbosch area and the Paarl area) may have more French ancestry because this is where most Huguenots in the Cape Colony where allocated for the purpose of wine-making.[51] Through the impact of the Huguenots in the Cape, French names became popular within the Afrikaans-speaking community (both White and Coloured) e.g. Jacques, Cheryl, Elaine, André, Michelle, Louis, Chantel/Chantelle, Leon, François, Jaden, Rozanne, Leroy, Monique, René, Lionel.[52][50] Due to integration with the Dutch and other ethnic groups in the Cape, many Afrikaans surnames are of French origin e.g. Delport, Nel, Du Preez, Le Roux, De Villiers, Joubert, Marais, Du Plessis, Visagie, Pienaar, De Klerk(from 'Le Clerc'), Fourie, Theron, Cronje, Viljoen (from 'Villion'), Du Toit, Reyneke, Malan, Naude, Terblanche, De Lille, Fouche, Minnaar, Blignaut, Retief, Boshoff, Rossouw, Olivier and Cilliers.[53]

During the 1600s and the 1700s, Germany was the Netherlands' biggest trading partner in Europe and due to good relations, more than 100 000 Germans were recruited by the VOC making Germans the largest foreign Europeans in the Dutch empire.[54] Throughout Dutch rule, the VOC sent nearly 15 000 Germans to the Dutch Cape Colony to work as officials, sailors, administrators and soldiers.[54] Just like the French Huguenots, the Germans in the Dutch Cape Colony were also assimilated into the existing Dutch community and also learnt Dutch which replaced German.[55] Eventually, Germans in the Cape became farmers, teachers, traders and ministers.[54] Almost all Germans who settled in the Cape throughout Dutch rule were men and therefore, almost all German men in the Cape married women outside their culture (including African and Asian women).[56][54] Due to integration with the Dutch and other ethnic groups in the Cape, there are many Afrikaans surnames of German origin e.g. Klaasen, Ackerman, Vosloo, Hertzog, Botha, Grobler, Hartzenberg, Pretorius, Booysen, Steenkamp, Kruger (from 'Krüger'), Louw, Venter, Cloete, Schoeman, Mulder, Kriel, Meyer, Breytenbach, Engelbrecht, Potgieter, Muller, Maritz, Liebenberg, Hoffman, Fleischman, Weimers, and Schuster.[57][58]

Another group of Europeans who settled in the Dutch Cape Colony came from Northern Europe (also known as 'Scandinavia'). In fact, they were amongst the earliest Europeans who settled in the Cape Colony, along with the Dutch and the Germans. Most Scandinavians in the Cape were VOC workers while others were independent traders who also needed the Cape as a halfway point to Asia and vice versa.[59] The Scandinavians in the Cape mostly came from Sweden and Denmark while a few came from Norway and Finland.[60] As the VOC struggled to find Dutch volunteers to become workers, it turned to the Scandinavians. Scandinavians in the Cape were mostly missionaries, soldiers, administrators, traders, teachers, nurses, doctors and public servants.[60] One of the earliest Scandinavians to settle in the Cape was the Danish husband of Krotoa, Peter Havgard, whose Dutch name was 'Pieter Van Meerhof'.[60] One of the most prominent Scandinavians in the Cape was the Swedish explorer and VOC official, Olof Bergh (whose wife, Anna De Konnning, was mixed-race).[60] Just like many White-Afrikaans speakers, many Cape Coloureds also have some ancestry from Northern Europe (especially Sweden and Denmark) because of these Scandinavians who integrated with the Dutch and other ethnic groups in the Cape region.[60] The common Afrikaans surname 'Trichardt'/'Triegaardt' originates from the Swedish surname 'Trädgård'.[60] Other surnames of Scandinavian origin became part of the Afrikaans-speaking community e.g. Zeederberg, Knoetze, Blomerus, Wentzel, Lindeque/Lindeques (from the Swedish surname 'Lindequast').[60]

Some of the Portuguese people also settled in the Cape and they were also integrated into the Cape society, which is how the Portuguese surname 'Ferreira' ended up being an Afrikaans surname as well.[61] Overtime, the white community of the Cape evolved into an ethnic group of White South Africans who are now known as Boers/Afrikaners.

With the arrival of more Europeans (as mentioned above), more African and Asian slaves and the recruitment of more Khoi Khoi labourers in the Cape Colony, there were more interracial unions with more mixed-race children who were absorbed into the Cape Coloured community.[62][63][64] The recruitment of Khoi Khoi labourers and the importation of African and Asian slaves continued until the Cape fell under British rule in the early 1800s and eventually, these slaves and labourers were absorbed into the Cape Coloured community.[22][65]

The most notorious ethnic group of Asian slaves in the Cape were the Malays who came from Indonesia while some also came from Malaysia.[66] Indonesian slaves were also made up of other tribes (such as the Javanese people from the island of Java and the Balinese people from the island of Bali).[67] Because Indonesia and Malaysia are both predominantly Muslim states, the slaves who were taken from these countries were the ones who introduced Islam into the Dutch Cape Colony, and Islam became the second-largest religion amongst Cape Coloureds, after Christianity.[68] Like the Christians, these Muslims also spread Islam through missionary work, hence it became the second-largest religion amongst Cape Coloureds.[69] Indonesian Muslims were also known as 'Mardyckers' or 'Mardijkers'.[70] However, many Indonesians were also non-Muslims, therefore, they also converted to Christianity. Many Indonesians were also sent to the Dutch Cape Colony as exiled prisoners who ended up as slaves as a punishment for rebelling against Dutch rule in Indonesia (which was then called the Dutch East Indies).[71] These Malays and other Indonesians had the largest non-European influence in the Cape Colony under Dutch rule.[72] The main reason behind this influence was that, unlike other enslaved ethnic groups in the Cape, Malay slaves and other Indonesian slaves were also royals, clerks, former politicians and former religious leaders who were initially brought as exiled prisoners; therefore, they used their influence and power to become prominent figures amongst the oppressed and enslaved people of the Cape.[72] These exiled prisoners include Tuan Guru (an exiled Indonesian prince who founded the first mosque in South Africa, which is located in the Bo-kaap, Cape Town) and Sheikh Yusuf (an Indonesian Muslim who was exiled to the Cape. The town of Macassar near Cape Town was named after his hometown, Makassar in Indonesia).[72] Through the influence of these Indonesians, Islam also became a refuge for other slaves and for Khoi Khoi labourers.[73]

Although the majority of Malays (together with other Indonesian slaves and Malaysian slaves) in the Cape were interracially mixed into the Cape Coloured community, a small minority of them preserved their own community in order to keep their culture and influence alive, therefore, they became known as the 'Cape Malays' (also known as the 'Cape Muslims').[74] Because of their influence, other Muslims in the Cape were eventually absorbed into the Cape Malay community (especially Indian slaves, East African slaves and the latter immigrants and indentured labourers from the Middle East, North Africa, Turkey, India, Indonesia and Zanzibar who settled when the Cape Colony was under British rule, during the 1800s and the early 1900s), therefore the Cape Malays were also creolised.[69] To a smaller extent, even Khoi Khoi people, Coloured/mixed-race people and White people who converted to Islam and followed Malay traditions were also assimilated into the Cape Malay community.[75][76] Due to many similarities between the Cape Coloureds and the Cape Malays, the two communities became intertwined, especially in Cape Town, which is the heart of the Cape Malay community in South Africa.[72] With the expansion of the Cape Colony, the spreading of Islam and other factors, many Cape Malays migrated to different parts of the Cape region; with some going as far as Port Elizabeth to the East while others went as far as Kimberly to the North.[77][78][79][80] Some Cape Malays even went beyond the Cape region and migrated into the interior of South Africa, especially after the discovery of gold in Johannesburg in 1886.[77][81] However, during Apartheid, the Cape Malays were classified as a sub-group of 'Coloureds' due to similar ancestry with the Cape Coloureds and because the Population Registration Act, 1950 grouped South Africa's population into four races: Black, White, Coloured and Indian.[82] Therefore, many Cape Malays were forced to live in Coloured communities under the Group Areas Act during Apartheid.[77]

Before the arrival of the Malays, the first Asian slaves brought to the Cape were Indians, followed by Sri Lankans and Bangladeshis (also known as 'Bengali'). Due to its spices and other goods, India was a vital trading-partner for the Netherlands, and hence for the Dutch East India Company. Within the same era that the Cape was colonised, the Dutch also colonised parts of India, Sri Lanka and Bengal.[83] From the beginning of slavery until the Cape fell under British rule in the early 19th centrury, many Indians, Sri Lankans and Bangladeshis were brought to the Cape as slaves. These South Asian slaves were mostly farmworkers, carpenters, craftsmen, domestic workers and cooks. One of the earliest and most prominent Indian slaves in the Cape was Angela Van Bengale (who hailed from the region of Bengal), who had a marriage and relationships with different white men and conceived 10 mixed-race children. At one stage, Indians formed the largest group of Asian slaves until their numbers dropped during the 18th century due to the restricted importation of Asian slaves.[84] Due to large-scale miscegenation, the majority of Indian slaves, Sri Lankan slaves and Bangladeshi slaves in the Cape were interracially mixed into the Cape Coloured community, while the minority of these South Asian slaves (who were Muslims) were assimilated into the Cape Malay community.[85][86] These Indians also influenced Cape Malay cuisine (with dishes such as butter chicken, roti, samosas, chicken ahni, biryani, fish curry, chicken curry, other curries, and the use of many spices), which, in turn, influenced the traditional dishes of the Cape Coloured community especially in the current Western Cape.[87]

The predominant African slaves in the Cape were the Southern African Bantu (who mostly came from the areas of present-day Mozambique and Angola) and the Malagasy people from Madagascar.[88] African slaves were also imported from Central Africa, West Africa, East Africa and Mauritius.[89] The very first slave ship to arrive in the Cape was the Amersfoort, which carried slaves from Angola.[90] The second large group of slaves also came from West Africa.[90] In fact, African slaves formed the majority of the slave population in the Dutch Cape Colony.[91][24] The slaves from Mozambique and its surroundings were locally known as 'Masbiekers', which was a Cape Dutch term that referred to Mozambicans.[24] To a certain extent, even slaves from East Africa were also known as 'Masbiekers' because most of them sailed passed the Island of Mozambique before they arrived in the Cape. The Masbiekers Valley in Swellendam (also known as 'Masbiekers Kloof') was named as a refuge for the freed Masbieker slaves who had nowhere to go after slavery was abolished.[92] The Bantu slaves (from different parts of Southern Africa, Central Africa and East Africa) also introduced the Ngoma drum, which became an instrument used during the Kaapse Klopse.[93][94] The word 'Ngoma' refers to a drum in most Bantu languages while it also refers to a song in some Bantu languages. Due to the Dutch influence and the massive creolisation, the word 'Ngoma' was creolised into 'Gomma' and it evolved into the term 'Ghoema'.[94] Due to the large-scale miscegenation, the majority of African slaves in the Cape were interracially mixed into the Cape Coloured community.[24] African slaves who were Muslims (especially from East Africa, West Africa and Madagascar) were also assimilated into the Cape Malay community.[69]

During the 17th century (in this case, from 1652 to 1700), the Dutch Cape Colony consisted only of present-day Cape Town with its surrounding areas (such as Paarl, Stellenbosch, Franschhoek etc.).[95] From the 18th century until the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, the territory of the Cape expanded gradually to the north and east.[96] The expansion of the Dutch Cape Colony was mainly caused by the dry and infertile nature of its immediate interior, therefore farmers needed fertile land because farms could only be settled where there were springs to provide permanent water.[96] However, the expansion was also influenced by emigration of the Trekboers (who left the Dutch Cape Colony and migrated into the Karoo) during the 18th century and by British rule during the 19th century.[97] By the 1750s, the territory of the Dutch Cape Colony had reached present-day Swellendam and by the end of the Dutch rule (after British annexation in 1814), the territory of the Cape had already reached certain parts of present-day Eastern Cape and the Northern Cape, leading to the arrival of Afrikaners/Boers with their multiracial slaves in different parts of the Cape.[98] When the Cape fell under British rule during the 19th century, it continued to expand until it reached the border with other colonies and with the Boer republics. With the gradual expansion of the Cape, the migration of the trekboer, the migration of Afrikaners/Boers with their multiracial slaves and the additional arrival of various European nationalities (such as the British, Irish etc.), there were more interracial unions throughout the Cape: this time between the white and the Khoisans in present-day Northern Cape, and between the white and the Xhosa in present-day Eastern Cape, with more mixed race children being conceived, who also became part of the Cape Coloureds.[99]

Miscegenation in the eastern part of the Cape (which is now the 'Eastern Cape') dates to the late 1600s which began as a result of the shipwrecks.[100] The Wild Coast Region of the Eastern Cape (which stretches from the provincial border with Natal to East London and Port Alfred) is named after its wilderness and the stormy seas that caused thousands of shipwrecks, especially during the 1700s.[101] Survivors of the shipwrecks (most of whom were Europeans while some were Asians) settled on the Wild Coast. Having no means to reach their intended destination, most survivors remained permanently in the Eastern Cape and mixed with the Xhosa.[102][103] Within the same period, many escaped slaves from the Dutch Cape Colony (also known as 'Maroons') fled to the East where they sought refuge and then they were soon followed by the Trekboers who were on their way to the Karoo, while some of them also settled in the Eastern Cape where they mixed with the Xhosa and the Khoi Khoi. The most notorious Trekboer to do so was Coenraad De Buys, who fathered many mixed race children with his many African wives (who were Khoi Khoi and Xhosa) and one of them was Chief Ngqika's mother, Yese, wife of Mlawu kaRarabe.[104] During the last years of Dutch rule, the territory of the Dutch Cape Colony had reached the Western portion of the Eastern Cape, especially in the Graaff-Reinet region which led to the arrival of Boers/Afrikaners with their multiracial slaves.[105][106] Miscegenation in the Eastern Cape continued during the 1800s until the early 1900s with the arrival of British, Irish and German settlers, many of whom had mixed with different ethnicities and eventually multiracial people in the Eastern Cape also became part of the Cape Coloured.[99]

In the Northern region of the Cape (which is now the 'Northern Cape'), miscegenation began in the 1700s, shortly after the arrival of the Trekboers that left the Dutch Cape Colony (fleeing from autocratic rule) and many settled in the Karoo while some settled in Namaqualand.[107] Some Trekboers even went as far as the Orange River and beyond to the Southern part of the Kalahari and in all these areas, they met the Khoisans (the San and the Khoi Khoi).[108] To survive in this hot and dry region, the Trekboers adopted the nomadic lifestyle of the Khoisans and some even mixed with the Khoisans.[109][110] During the last years of Dutch rule, the territory of the Dutch Cape Colony had reached the Southern portion of the Northern Cape, leading to the arrival of Boers/Afrikaners with their multiracial slaves.[96] In the early 1800s, the Griqua people left the Dutch Cape Colony and half of them migrated to the North of the Karoo where they established a Griqua state called 'Griqualand West'.[111] Then the Basters, Oorlams and some Cape Coloureds migrated to the North as well and some of them even went as far as present-day Namibia.[112] In the latter half of the 1800s, large sums of diamond, Uranium, Copper and Iron ore were discovered in the Northern Cape which attracted many Europeans, many of whom mixed with the San, Khoi khoi, Tswana in the North-East and the Xhosa in the South-East and then multiracial people in the Northern Cape also became part of the Cape Coloured.[113][114][112]

After British annexation in 1814, slavery was abolished in the Cape in 1834, which lead to the Great Trek when the Boers left the Cape as Voortrekkers and migrated into the interior of South Africa to form the Boer republics.[115] Most of the freed slaves (who became Cape Coloureds) remained behind. Many freed slaves moved to an area in Cape Town that became known as District Six. Throughout the 1800s (especially after the abolishment of slavery in 1834) and the early 1900s, the Cape received an influx of refugees, immigrants and indentured labourers from: Britain, Ireland, Germany, Lithuania, St Helena, China, Indonesia, the Philippines, India, Middle East, West Africa, North Africa and East Africa(majority of all these groups were absorbed into the Cape Coloured community).[116][117][118]

In the 1800s, the Philippines, at the time a Spanish colony, experienced a harsh rebellion against Spanish colonial rule, so many Filipinos fled to different parts of the world. In the late 1830s, the first Filipinos to arrive in the Cape settled in Kalk Bay, Cape Town where they fished for a living and then Kalk Bay became their new home.[119] When word reached the Philippines, many more Filipinos flocked to Kalk Bay, and they were soon scattered throughout Cape Town and other parts of the region that is now the Western Cape, where most of them were eventually absorbed into the Cape Coloured community.[120] As a result, many Cape Coloureds can trace some of their roots to the Philippines due to the Filipinos of Kalk Bay.[116] Many Filipinos who settled in the Cape were also mixed with some Spanish ancestry as a result of the Spaniards who mixed with the indigenous people of the Philippines while some were simply Spanish Filipinos of Spanish descent, therefore, some Cape Coloureds can also trace some of their roots to Spain due to the Filipinos of Kalk Bay.[116] Within the Cape Coloured community, surnames from the Filipinos of Kalk Bay (which are mostly Spanish surnames that the Filipinos got from the Spaniards) are Gomez, Pascal, Torrez, De La Cruz, Fernandez, Florez(also spelt as 'Floris'), Manuel, and Garcia.[116]

In 1888, Oromo slave children from Ethiopia (who were headed for Arabia) were rescued and freed by British troops.[121] In 1890, the British troops brought these freed Oromo slaves to Lovedale Mission in present-day Eastern Cape where many of them became part of the Cape Coloured.[121] The late Dr Neville Alexander's grandmother, Bisho Jarsa, was a freed Oromo slave from Ethiopia.[122]

By the turn of the 20th century, District six became more established and cosmopolitan. Although its population was predominantly Cape Coloured, District Six (just like many places in the Cape) was diverse with different ethnicities, races and nationalities living there (this includes Blacks, Whites, Jews, Cape Malays and Asian immigrants such as the Indians, Chinese, Japanese etc.)[123] Many of these groups were absorbed into the Cape coloured community.[124] The whole Cape Colony (including the Eastern Cape and the Northern Cape) also attracted many European immigrants of various nationalities (including Scandinavians, Portuguese, Greeks, Italians etc.), many of whom married into the Cape Coloured community while some mixed with other ethnic groups, whose children were absorbed into the Cape Coloured community, further diversifying the ancestry of Cape Coloureds.[35][125][126]

During the 20th century (under British rule from 1910 to 1948 and Apartheid regime from 1948 to 1994), many Khoisans living in the Cape Province were assimilated into the Cape Coloured community, especially in the North of the Cape (now the 'Northern Cape').[127] As a result, many Cape Coloureds, especially from the Northern Cape, share close ties with the San and the Khoi Khoi, especially those living in the Namaqualand region, around the Orange river and the Kalahari region.[128]

As a result, the Cape Coloureds ended up having the most diverse ancestry in the world, with a blend of many different cultures.[129]

Cape Coloureds in the media

[edit]

A group of Cape Coloureds were interviewed in the documentary series Ross Kemp on Gangs. One of the gang members who participated in the interview mentioned that black South Africans have been the main beneficiaries of South African social promotion initiatives while the Cape Coloureds have been further marginalised.[citation needed]

The 2009 film I'm Not Black, I'm Coloured – Identity Crisis at the Cape of Good Hope (Monde World Films, US release) is one of the first historical documentary films to explore the legacy of Apartheid through the viewpoint of the Cape Coloured community, including interviews with elders, pastors, members of Parliament, students and everyday people struggling to find their identity in the new South Africa. The film's 2016 sequel Word of Honour: Reclaiming Mandela's Promise (Monde World Films, US release) [130]

Various books have covered the subject matter of Coloured identity and heritage.[who?]

Patric Tariq Mellet, heritage activist and author of 'The Camissa Embrace' and co-creator of The Camissa Museum, has composed a vast online blog archive ('Camissa People') of heritage information concerning Coloured ancestry tracing to the Indigenous San and Khoe and Malagasy, East African, Indonesian, Indian, Bengal and Sri Lankan slaves.[citation needed]

Terminology

[edit]The term "coloureds" is currently treated as a neutral description in Southern Africa, classifying people of mixed race ancestry. "Coloured" may be seen as offensive in some other western countries, such as Britain and the United States of America.[131]

The most used racial slurs against Cape Coloureds are Hottentot or hotnot and Kaffir. The term "hotnot" is a derogatory term used to refer to Khoisan people and coloureds in South Africa. The term originated from the Dutch language, where "Hottentot" was used to describe a language spoken by the Khoisan people. It later came to be used as a derogatory term for the people themselves, based on European perceptions of their physical appearance and culture. The term is often used to demean and dehumanize Khoisan and coloured people, perpetuating harmful stereotypes and discrimination against them.[132] The term "Kaffir" is a racial slur used to refer to coloured people and black people in South Africa. It originated from Arabic and was used to refer to non-Muslims. Later, it was used by European-descended South Africans to refer to black and coloured people during the apartheid era, and the term became associated with racism and oppression. While it is still used against Coloured people, it is not as prevalent as it is against black people.[133][134]

People

[edit]Politicians

[edit]- Midi Achmat, South African writer and LGBT rights activist

- Zackie Achmat, South African HIV/AIDS activist and filmmaker

- Neville Alexander, Political activist, educationalist and lecturer.

- Allan Boesak, Political activist and cleric.

- Patricia de Lille, former PAC, then Independent Democrats leader, then Democratic Alliance mayor of Cape Town, now leader of Good Party

- Tony Ehrenreich, South African trade unionist.

- Zainunnisa Gool, South African Political activist and representative on the Cape Town City Council.

- Alex La Guma, South African novelist and leader of the South African Coloured People's Organisation.

- Trevor Manuel, former Finance Minister, currently Head of the National Planning Commission of South Africa.

- Peter Marais, former Unicity Mayor of Cape Town and Former Premier of the Western Cape

- Gerald Morkel, former mayor of Cape Town

- Dan Plato, Western Cape Community Safety Minister.

- Dulcie September, political activist.

- Adam Small, political activist, poet and writer.

- Percy Sonn, former president of the International Cricket Council.

- Simon van der Stel, last commander and first Governor of the Dutch Cape Colony.

Artists and writers

[edit]- Peter Abrahams, writer

- Tyrone Appollis, academic

- Willie Bester

- Dennis Brutus, journalist, poet, activist

- Peter Clarke

- Phillippa Yaa de Villiers, writer and performance artist

- Garth Erasmus, artist

- Diana Ferrus, poet, writer and performance artist

- Oliver Hermanus, writer, director

- Rozena Maart, writer

- Mustafa Maluka

- Dr. Don Mattera

- James Matthews, writer

- Selwyn Milborrow, poet, writer, journalist

- Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh

- Arthur Nortje, poet

- Robin Rhode

- Richard Moore Rive, writer

- Tracey Rose

- Adam Small, writer

- Zoë Wicomb, writer

- Athol Williams, poet, writer, scholar, social philosopher

Actors and actresses

[edit]- Quanita Adams, actress

- Natalie Becker, actress

- Lesley-Ann Brandt, actress

- Meryl Cassie, actress

- Vincent Ebrahim, actor

- Vinette Ebrahim, actress

- Kim Engelbrecht, actress

- Jarrid Geduld, actor

- Shannon Kook, actor

- Kandyse McClure, actress

- Shamilla Miller, actress

- Blossom Tainton-Lindquist

Beauty queens

[edit]- Tansey Coetzee, Miss South Africa 2007

- Tamaryn Green, Miss South Africa 2018

- Pearl Jansen, Miss World 1st runner up 1970, competed as Miss Africa South due to Apartheid

- Amy Kleinhans, former Miss South Africa 1992 and first non-white Miss South Africa.

- Liesl Laurie, Miss South Africa 2015

- Jo-Ann Strauss, Miss South Africa 2000, media personality and business woman.

Musicians

[edit]- AKA, hip-hop recording artist

- Fallon Bowman, South African-born guitarist, singer, and actor.

- Jonathan Butler, jazz musician.

- Blondie Chaplin, singer and guitarist for the Beach Boys.

- Paxton Fielies, singer

- Jean Grae, hip-hop artist.

- Paul Hanmer, pianist and composer

- Abdullah Ibrahim, jazz pianist

- Robbie Jansen, musician

- Trevor Jones, South African-born film composer.

- Taliep Petersen, musician and director

- YoungstaCPT, rapper

Others

[edit]- Marc Lottering, comedian

- Jenny Powell, television presenter.

Athletics

[edit]- Shaun Abrahams, 800m runner

- Cornel Fredericks, track-and-field sprinter

- Paul Gorries, Sprinter

- Leigh Julius, 2004–08 Olympian

- Geraldine Pillay, 2004 Olympian, Commonwealth medallist

- Wayde van Niekerk, track-and-field sprinter, Olympic and World Champion, and World Record Holder

Cricket

[edit]- Paul Adams

- Vincent Barnes

- Loots Bosman

- Henry Davids

- Basil D'Oliveira

- Damian D'Oliveira

- JP Duminy

- Herschelle Gibbs

- Beuran Hendricks

- Reeza Hendricks

- Omar Henry

- Garnett Kruger

- Charl Langeveldt

- Wayne Parnell

- Alviro Petersen

- Robin Peterson

- Keegan Petersen

- Vernon Philander

- Dane Piedt

- Ashwell Prince

- Roger Telemachus

- Clyde Fortuin

- Ottniel Baartman

Field hockey

[edit]Football

[edit]- Keegan Allan

- Kurt Abrahams

- Cole Alexander

- Oswin Appollis

- Andre Arendse

- Tyren Arendse

- Wayne Arendse

- Bradley August

- Brendan Augustine

- Emile Baron

- Shaun Bartlett

- Tyrique Bartlett

- David Booysen

- Mario Booysen

- Ethan Brooks

- Delron Buckley

- Brent Carelse

- Daylon Claasen

- Rivaldo Coetzee

- Keanu Cupido

- Clayton Daniels

- Lance Davids

- Rushine De Reuck

- Keagan Dolly

- Kermit Erasmus

- Jody February

- Taariq Fielies

- Quinton Fortune

- Lyle Foster

- Bevan Fransman

- Stanton Fredericks

- Reeve Frosler

- Ruzaigh Gamildien

- Morgan Gould

- Victor Gomes, referee

- Travis Graham

- Ashraf Hendricks

- Rowan Human

- Rudi Isaacs

- Willem Jackson

- Moeneeb Josephs

- David Kannemeyer

- Ricardo Katza

- Daine Klate

- Lyle Lakay

- Lee Langeveldt

- Clinton Larsen

- Luke Le Roux

- Stanton Lewis

- Benni McCarthy, South Africa national team's all-time top scorer with 31 goals

- Fabian McCarthy

- Leroy Maluka

- Grant Margeman

- Bryce Moon

- Nasief Morris

- Tashreeq Morris

- James Musa

- Andile Ncobo, referee

- Morne Nel

- Andras Nemeth

- Reagan Noble

- Brad Norman

- Riyaad Norodien

- Bernard Parker

- Genino Palace

- Peter Petersen

- Brandon Peterson

- Steven Pienaar

- Reyaad Pieterse

- Wayne Roberts

- Frank Schoeman

- Ebrahim Seedat

- Brandon Silent

- Elrio van Heerden

- Dino Visser

- Shu-Aib Walters

- Mark Williams, scored both goals to win the 1996 African Cup of Nations final

- Ronwen Williams

- Robyn Johannes

Rugby

[edit]- Gio Aplon

- Nizaam Carr

- Kurt Coleman, Western Province and Stormers player

- Bolla Conradie

- Juan de Jongh

- Peter de Villiers

- Justin Geduld, Sprinbok 7's

- Bryan Habana

- Cornal Hendricks

- Adrian Jacobs

- Conrad Jantjes

- Elton Jantjies

- Herschel Jantjies

- Ricky Januarie

- Ashley Johnson

- Cheslin Kolbe, Western Province and Stormers player

- Dillyn Leyds, Western Province and Stormers player

- Lionel Mapoe

- Breyton Paulse

- Earl Rose

- Tian Schoeman

- Errol Tobias

- Jaco van Tonder

- Ashwin Willemse

- Chester Williams

Others

[edit]- Christopher Gabriel – basketball player

- Raven Klaasen – tennis player

- Devon Petersen – darts player

- Kenny Solomon – South Africa's first chess grandmaster

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Census 2022: Statistical Release" (PDF). statssa.gov.za. 10 October 2023. p. 6. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "The Coloureds of Southern Africa". MixedFolks.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- ^ Khan, Razib (16 June 2011). "The Cape Coloureds are a mix of everything". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "STATISTICAL RELEASE P0301.4 Census 2022" (PDF). census.statssa.gov.za.

- ^ Stell, Gerald (2010). "Ethnicity in linguistic variation". Pragmatics. 20 (3): 425–447. doi:10.1075/prag.20.3.06ste. ISSN 1018-2101.

- ^ Calafell, Francesc; Daya, Michelle; van der Merwe, Lize; Galal, Ushma; Möller, Marlo; Salie, Muneeb; Chimusa, Emile R.; Galanter, Joshua M.; van Helden, Paul D.; Henn, Brenna M.; Gignoux, Chris R.; Hoal, Eileen (2013). "A Panel of Ancestry Informative Markers for the Complex Five-Way Admixed South African Coloured Population". PLOS ONE. 8 (12) e82224. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...882224D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082224. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3869660. PMID 24376522.

- ^ a b Lankheet, Imke; Hammarén, Rickard; Caballero, Lucía Ximena Alva; Larena, Maximilian; Malmström, Helena; Jolly, Cecile; Soodyall, Himla; Jongh, Michael de; Schlebusch, Carina (22 July 2025). "Wide-scale Geographical Analysis of Genetic Ancestry in the South African Coloured Population". BMC Biology. 23 (1) 219. doi:10.1186/s12915-025-02317-5. PMC 12281806. PMID 40696318.

- ^ Petersen, Desiree C.; Libiger, Ondrej; Tindall, Elizabeth A.; Hardie, Rae-Anne; Hannick, Linda I.; Glashoff, Richard H.; Mukerji, Mitali; Indian Genome Variation Consortium; Fernandez, Pedro; Haacke, Wilfrid; Schork, Nicholas J.; Hayes, Vanessa M. (14 March 2013). Williams, Scott M. (ed.). "Complex Patterns of Genomic Admixture within Southern Africa". PLOS Genetics. 9 (3) e1003309. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003309. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 3597481. PMID 23516368.

- ^ "AncestrySupport".

- ^ "Books: Author highlights Asian slavery at Cape of Good Hope".

- ^ "Anna van Bengale - Camissa Museum".

- ^ "2: African & Asian Enslaved Peoples - Camissa Museum".

- ^ Dhupelia-Mesthrie, Uma (2009). "The Passenger Indian as Worker: Indian Immigrants in Cape Town in the Early Twentieth Century". African Studies. p. 111.

- ^ Carter, R. Colin; Yang, Zikun; Akkaya-Hocagil, Tugba; Jacobson, Sandra W.; Jacobson, Joseph L.; Dodge, Neil C.; Hoyme, H. Eugene; Zeisel, Steven H.; Meintjes, Ernesta M. (1 April 2024). "Genetic admixture predictors of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) in the South African Cape Coloured population". medRxiv 10.1101/2024.03.31.24305130.

- ^ Pfennig, Aaron; Petersen, Lindsay N; Kachambwa, Paidamoyo; Lachance, Joseph (6 April 2023). Eyre-Walker, Adam (ed.). "Evolutionary Genetics and Admixture in African Populations". Genome Biology and Evolution. 15 (4) evad054. doi:10.1093/gbe/evad054. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 10118306. PMID 36987563.

- ^ "Who are the Cape Coloureds of South Africa?". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ^ Barbieri, Chiara; Vicente, Mário; Rocha, Jorge; Mpoloka, Sununguko W.; Stoneking, Mark; Pakendorf, Brigitte (7 February 2013). "Ancient Substructure in Early mtDNA Lineages of Southern Africa". American Journal of Human Genetics. 92 (2): 285–292. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.12.010. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 3567273. PMID 23332919.

- ^ Afrikaans-Speaking Catholics in the Rainbow Republic, Catholic World News, 14 November 1996.

- ^ "Cape Melting Pot the Role and Status of the Mixed Population at the Cape 1652-1795".

- ^ "Who are the Cape Coloureds of South Africa?".

- ^ "How Indigenous South Africans Resisted the First European Intruders". 24 October 2023.

- ^ a b "The Early Cape Slave Trade | South African History Online".

- ^ Groenewald, Gerald (2010). "Slaves and Free Blacks in VOC Cape Town, 1652–1795". History Compass. 8 (9): 964–983. doi:10.1111/J.1478-0542.2010.00724.X.

- ^ a b c d Skies, Infinite (10 March 2019). "CAMISSA HERITAGE - Origin and History of South African Cape Coloured People".

- ^ Groenewald, Gerald (2010). "Slaves and Free Blacks in VOC Cape Town, 1652–1795". History Compass. 8 (9): 964–983. doi:10.1111/J.1478-0542.2010.00724.X.

- ^ "The First Slaves at the Cape | South African History Online".

- ^ Groenewald, Gerald (2010). "Slaves and Free Blacks in VOC Cape Town, 1652–1795". History Compass. 8 (9): 964–983. doi:10.1111/J.1478-0542.2010.00724.X.

- ^ "The slave experience – Slavery in South Africa".

- ^ "I'm Not Black, I'm Coloured - South Africa (2009)". YouTube. 6 April 2024.

- ^ "History of slavery and early colonisation in South Africa | South African History Online".

- ^ a b "The Arrival of the Dutch: VOC, Cape Colony, and Early Settlers". History Rise. 27 February 2025.

- ^ "Cape Melting Pot the Role and Status of the Mixed Population at the Cape 1652-1795".

- ^ "Cape Melting Pot the Role and Status of the Mixed Population at the Cape 1652-1795".

- ^ "Cape Melting Pot the Role and Status of the Mixed Population at the Cape 1652-1795".

- ^ a b https://study.com/academy/lesson/cape-coloureds-origins-culture.html?msockid=31e14f9a4e30671f2e725b284f306666 [bare URL]

- ^ a b "History of Camissa People". 21 June 2019.

- ^ "The Coloured Communities of Southern Africa, a story".

- ^ "Krotoa (Eva) | South African History Online".

- ^ "Love in the time of imperialism: Krotoa 'Eva' van Meerhof | University of Cape Town".

- ^ "The Dutch Settlement | South African History Online".

- ^ https://www.candlewoodsvenue.co.za/images/CandlewoodsHistory.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Van Wyk Family: History of the van Wyk Family Name". 24 April 2007.

- ^ Worden, Nigel; Malan, Antonia (19 January 2017). "17 Constructing and Contesting Histories of Slavery at the Cape, South Africa".

- ^ "The Huguenot History".

- ^ https://huguenotsociety.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/HUGUENOT_SOCIETY-SA_History.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "The French Huguenots - Franschhoek, South Africa".

- ^ "Ranked: World's Biggest Wine Producers by Country". 18 August 2023.

- ^ De Bruin, Karen (2021). "From Viticulture to Commemoration: French Huguenot Memory in the Cape Colony (1688-1824)". Journal of the Western Society for French History.

- ^ "The first large group of French Huguenots arrive at the Cape | South African History Online".

- ^ a b Romero, Patricia (1 January 2004). "Encounter at the Cape: French Huguenots, the Khoi and Other People of Color". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. doi:10.1353/CCH.2004.0038.

- ^ https://huguenotsociety.org.za/

- ^ "Top 1,000 French Names (Male and Female)". Listophile. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "Huguenot surnames which exist in South Africa".

- ^ a b c d Olga Witmer (15 September 2020). "Germans, the Dutch East India Company, and Early Colonial South Africa". German Historical Institute London Blog. doi:10.58079/P1PG.

- ^ https://www.cdbooks-r-us.com/supportdocs/personaliapreface.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "German Immigrants to the Cape Colony under the Dutch 1652-1806".

- ^ "German influence on Boer-Afrikaner people". 17 November 2013.

- ^ "The meaning and history of the last name Grobler". 31 July 2024.

- ^ Winquist, Alan (January 1978). "Scandinavians and South Africa". Ayres Special Collection.

- ^ a b c d e f g https://pillars.taylor.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=ayres-collection-books

- ^ "The Ferreira Family in SA".

- ^ "The Cape Coloureds are a mix of everything".

- ^ "German Immigrants to the Cape Colony under the Dutch 1652-1806".

- ^ "The Huguenots in South Africa".

- ^ "Khoikhoi -Dutch relations - Aboriginal Khoikhoi Servants and Their Masters in Colonial Swellendam, - Studocu".

- ^ "South Africa's Forgotten Minority: The Cape Malays - Henri Steenkamp". 10 February 2017.

- ^ "CAMISSA HERITAGE: Indigenes, Slaves, Indentured Labour and Migrants of Colour at the Cape of Good Hope". 17 January 2018.

- ^ "History of Muslims in South Africa: 1700 - 1799 by Ebrahim Mahomed Mahida | South African History Online".

- ^ a b c https://naqshbandi.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/PAGES-FROM-CAPE-MUSLIM-HISTORY-V3.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Choudhury, Manilata (2014). "The Mardijkers of Batavia: Construction of a Colonial Identity (1619-1650)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 75: 901–910. JSTOR 44158475.

- ^ "The Cape Malay | South African History Online".

- ^ a b c d "The Cape Malay".

- ^ https://repository.up.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/32132c3b-2dca-4cc1-ab53-bb4f64d5c0ec/content

- ^ "The Preservation of Cape Malay Culture in Cape Town — plak.co.za". 27 March 2025.

- ^ https://taalmuseum.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Cape-Malay-a-South-African-Muslim-identity-borne-out-of-colonialism-aug-2021.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Da Costa, Yusuf (1992). "Assimilatory processes amongst the Cape Muslims in South Africa during the 19th century". South African Journal of Sociology. 23: 5–11. doi:10.1080/02580144.1992.10520103.

- ^ a b c "Conflict of Identities: The Case of South Africa's Cape Malays".

- ^ "Port Elizabeth of Yore: The Malays Create a Niche". 17 March 2017.

- ^ "History of Muslims in South Africa: 1652 - 1699 by Ebrahim Mahomed Mahida | South African History Online".

- ^ https://www.spu.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/03MalayCamp/AfricanaLibrary/03Newspaper_Documents/n.d.-Historical-view-of-the-Malay-Camp-p1-6.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Research Portal".

- ^ Vahed, Goolam (2004). "The Quest for 'Malay' identity in Apartheid South Africa". Alternation. 11. hdl:10520/AJA10231757_695.

- ^ "Indian Slaves in South Africa: Notes for monograph, 26 June 1995 | South African History Online".

- ^ "Indian Slaves in South Africa: Notes for monograph, 26 June 1995 | South African History Online".

- ^ https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-1541

- ^ "Indian Slaves in South Africa: Notes for monograph, 26 June 1995 | South African History Online".

- ^ "Cape Malay Cuisine".

- ^ "Slave Routes to the Cape – Slavery in South Africa".

- ^ "2: African & Asian Enslaved Peoples - Camissa Museum".

- ^ a b "Slave Routes to Cape Town – Slavery in South Africa".

- ^ "2: African & Asian Enslaved Peoples - Camissa Museum".

- ^ "History of Masbiekers Valley". Masbiekers Valley Project. 20 January 2019.

- ^ "The Cultural Significance of South African Ghoema Music: History, Instruments, and Social Role". 26 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Lydia Williams (Masbiekers) - Camissa Museum".

- ^ Guelke, Leonard (1985). "The Making of Two Frontier Communities: Cape Colony in the Eighteenth Century". Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques. 12 (3): 419–448. JSTOR 23232400.

- ^ a b c "The Cape Northern Frontier | South African History Online".

- ^ https://open.uct.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/6237124e-c438-4a5f-9990-3c611efae274/content [bare URL]

- ^ "Political changes from 1750 to 1820 | South African History Online".

- ^ a b "Southern Africa - European and African interaction in the 19th century | Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "Cape Identity". 19 May 2013.

- ^ "Ships wrecked | Wild Coast".

- ^ "Bessie, the white queen of the Mpondo of the Eastern Cape". 18 August 2022.

- ^ "Abelungu - A Xhosa clan that raised a shipwrecked white child into a Xhosa leader".

- ^ "De Buys Genealogy: Who was Coenraad de Buys?". 3 February 2011.

- ^ "Political changes from 1750 to 1820 | South African History Online".

- ^ "Graaff-Reinet | South African History Online".

- ^ "Trekboers of the Richtersveld".

- ^ "The Forgotten Highway – Ancestral Journeys – First with the News". 4 October 2024.

- ^ "Trekboers: Chapter 1 of 'The Great Trek'". www.ourcivilisation.com. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "South Africa - Emergence of a Settler Society". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "Griqualand West | South African History Online".

- ^ a b "5: Maroons, Orlam & Drosters - Camissa Museum".

- ^ "Republic of Griqualand West or the Digger's Republic | South African History Online".

- ^ Cairncross, Bruce (July 2004). "History of the Okiep copper district, Namaqualand, Northern Cape Province, South Africa". Mineralogical Record. 35 (4): 289–317.

- ^ "Slavery is abolished at the Cape | South African History Online".

- ^ a b c d Skies, Infinite (10 March 2019). "CAMISSA HERITAGE - Origin and History of South African Cape Coloured People".

- ^ "Lithuanian footsteps in South Africa". Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357167610_History_of_the_German_Settlers_in_the_Eastern_Cape [bare URL]

- ^ "History of Filipino community recognized in Kalk Bay! | the Heritage Portal".

- ^ https://www.kbha.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Bulletin-Number-1.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b Morton, Fred (9 May 2019). Leshilo, Thabo (ed.). "The story of Oromo slaves bound for Arabia who were brought to South Africa". doi:10.64628/AAJ.ts9kw33ck.

- ^ "Dr. Neville Edward Alexander | South African History Online".

- ^ "Why Cape Town's District Six – devastated so many years ago – is still vital". 14 February 2021.

- ^ "District Six: Exploring the Rich History of Cape Town's Iconic Neighbourhood". 12 April 2023.

- ^ "Italians in South Africa 1800 - Italy in Cape Town". 12 November 2022.

- ^ Chrysopoulos, Philip (8 June 2023). "The Turbulent Story of Greeks in South Africa". GreekReporter.com. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "Khoisan Identity | South African History Online". sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "NCESC". Discovering Employment Paths and Travel Experiences. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "Genome-wide analysis of the South African Coloured population in the Western Cape". ResearchGate. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ Szafraniec, Gina (3 April 2011). "Millions Will Watch". The Bloomington Crow. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "Is the word 'coloured' offensive?". BBC News. 9 November 2006. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed (17 November 2005). Not White Enough, Not Black Enough: Racial Identity in the South African Coloured Community. Ohio University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-89680-442-5.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed, editor. Burdened by Race: Coloured Identities in Southern Africa. UCT Press, 2013, pp. 69, 124, 203 ISBN 978-1-92051-660-4 https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/id/c0a95c41-a983-49fc-ac1f-7720d607340d/628130.pdf.

- ^ Mathabane, M. (1986). Kaffir Boy: The True Story of a Black Youth's Coming of Age in Apartheid South Africa. Simon & Schuster. (Chapter 2)

External links

[edit]- Adhikari, Mohamed (2005). Not White Enough, Not Black Enough: Racial Identity in the South African Coloured Community. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-442-5.

- Boggenpoel, Jesmane (2018). My Blood Divides and Unites: Race, Identity, Reconciliation. Porcupine Press. ISBN 978-1-928455-28-8.

- Richards, Ruben Robert (2018). Bastaards Or Humans: The Unspoken Heritage of Coloured People. Indaba. ISBN 978-1-947599-06-2.

- Van Wyk, Chris (2006). Shirley, Goodness & Mercy: A Childhood in Africa. Picador. ISBN 978-0-330-44483-5.

Cape Coloureds

View on GrokipediaTerminology and Identity

Etymology and Historical Usage

The term "Coloured," as applied to people of mixed ancestry in South Africa, derives from the English adjective denoting individuals with darker skin tones, adapted in the colonial context to specifically reference those of blended European, Khoisan, African slave, and Asian descent in the Cape region.[5] Its earliest documented use in this sense appears in 1829, during the British colonial period following the emancipation of Khoisan and slaves between 1828 and 1834, when it began distinguishing such populations from both Europeans and indigenous "natives."[5][6] By the late 19th century, "Coloured" emerged as a self-descriptor among freed slaves and their descendants in Cape Town, particularly between 1875 and 1910, amid economic shifts like the 1867-1886 diamond and gold discoveries that heightened competition with incoming African laborers and prompted assertions of a distinct urban identity tied to Christianity, wage labor, and partial legal privileges under British rule.[6] The 1891 Cape Colony census formally employed "coloured" for non-Europeans of mixed race, refining it to "mixed race" by 1904, reflecting its consolidation as a socio-legal category amid growing segregationist policies.[6] In the Cape context, "Cape Coloured" specifically denoted this localized group, contrasting with inland subgroups like Griquas, and emphasized creole cultural elements over pure indigenous or slave origins. Under the Union of South Africa from 1910 and later apartheid, the term rigidified through legislation, including the 1923 Natives (Urban Areas) Act and the 1950 Population Registration Act, which classified "Coloured" as a hereditary racial group based on appearance, descent, and social habits, excluding those deemed assimilable into whiteness.[5] This usage, while initially pragmatic for freed populations seeking separation from African "natives" to access voting rights and urban opportunities in the Cape, evolved into a tool of state-imposed hierarchy, prompting post-1970s critiques often marked by inverted commas to signal rejection of artificial ethnic engineering.[5][6]Modern Identity Debates and Nationalism

In post-apartheid South Africa, Cape Coloured communities have engaged in ongoing debates over the retention or rejection of the "Coloured" label, often viewing it as a remnant of apartheid-era racial classification that obscures diverse ancestries including Khoisan, European, and Bantu elements. Some individuals and activists reject the term outright, arguing it perpetuates a derogatory colonial construct and advocate instead for self-identification as Black, Khoisan, or simply South African to align with non-racial ideals or indigenous roots, influenced by Black Consciousness movements.[7][8] However, empirical studies indicate that a majority in regions like the Western Cape continue to embrace "Coloured" as a marker of distinct cultural hybridity, particularly tied to Afrikaans language, Christian affiliations, and unique social histories that differentiate them from both White and Black African groups.[9][10] These identity tensions have manifested in assertions of separateness from broader "Black" categories, with many Cape Coloureds resisting assimilation into BEE (Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment) frameworks that prioritize Bantu-descended Africans, citing feelings of marginalization in post-1994 policies and cultural erasure. Surveys and qualitative research from the Western and Northern Cape reveal widespread reluctance to adopt apartheid-rejected labels under a unified "Black" banner, driven by historical privileges under segregation that positioned Coloureds above Blacks but below Whites, fostering a persistent "in-between" consciousness.[7] Politically, this has fueled debates over representation, as seen in 2020 public controversies questioning Coloured cultural validity, which elicited strong defenses of community-specific traditions like Cape Malay influences and Kaapse Klopse minstrel troupes. Coloured nationalism has gained traction as a response, exemplified by the entry of explicitly Coloured-focused parties into national politics following the 2024 elections, including the National Coloured Congress (NCC), which prioritizes issues like gang violence in Coloured-majority townships and equitable resource allocation in the Western Cape. The Patriotic Alliance (PA), while broader, has amplified Coloured-specific grievances in Parliament, advocating for recognition of distinct ethnic needs amid perceptions of ANC-led governance favoring Black African constituencies.[12] Critics, including some academics and commentators, warn that such nationalism risks exacerbating divisions in a rainbow nation framework, potentially undermining coalition-building, though proponents argue it counters systemic underrepresentation, as Coloureds comprise about 8.8% of the population yet hold limited proportional influence in national structures.[13] This movement reflects causal pressures from post-apartheid economic disparities, where Coloured unemployment rates in the Western Cape hovered around 25% in 2023, higher than White but comparable to Black rates, prompting demands for targeted interventions without subsuming into pan-Black narratives.[12]Demographics

Population and Geographic Distribution

The Coloured population of South Africa, predominantly Cape Coloureds, totaled approximately 5.1 million individuals as of the 2022 census, representing 8.2% of the national population of 62 million.[3] [14] This figure reflects a modest increase from the 4.6 million recorded in the 2011 census, driven by natural growth despite lower fertility rates compared to the Black African majority.[14] Cape Coloureds are overwhelmingly concentrated in the Western Cape province, where they comprise about 42% of the 7.4 million residents, equating to roughly 3.1 million people.[14] [15] Within the City of Cape Town metropolitan area, which houses over half of the province's population, Coloureds form 35% of the approximately 4.8 million inhabitants, with significant communities in suburbs and townships such as Mitchells Plain, Athlone, and Bishop Lavis.[15] They also constitute a substantial portion—around 48%—of the Northern Cape's smaller population of 1.3 million, particularly in urban centers like Kimberley.[14] Smaller but notable presences exist in the Eastern Cape's eastern districts and urban Gauteng, where migration has led to communities in Johannesburg and Pretoria.[16] Outside South Africa, a diaspora of Cape Coloured descendants exists in Namibia, where they number around 40,000 and are known as Basters or Rehoboth Basters in specific settlements, though this group maintains distinct cultural ties.[17] Overall, over 85% of South Africa's Coloured population resides in the Western Cape, underscoring their historical roots in the Cape region from colonial settlement patterns.[17] Urbanization remains high, with most Cape Coloureds living in cities and peri-urban areas rather than rural locales.[18]Genetic Ancestry and Admixture Studies

The Cape Coloured population, also known as the South African Coloured (SAC) group, displays one of the highest levels of genetic admixture globally, stemming from intermixing between indigenous Khoisan foragers and herders, European settlers primarily from the Netherlands and France, Bantu-speaking African populations, and enslaved individuals from South and Southeast Asia, Madagascar, East Africa, and West Africa during the colonial era.[2] Genome-wide analyses using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data and tools like ADMIXTURE and STRUCTURE have quantified these contributions, revealing no single dominant ancestry but rather a mosaic shaped by historical migrations, slavery, and settlement patterns from the 17th century onward.[1][19] Early comprehensive genotyping of 959 Western Cape individuals in 2010 estimated average ancestry as 32–43% Khoisan, 20–36% Bantu-speaking African, 21–28% European, and 9–11% Asian, with linkage disequilibrium patterns indicating admixture events predating the 19th century.[1] A 2013 study employing proxy ancestry selection on 764 SAC genomes refined this to approximately 31% Khoisan (proxied by ‡Khomani San), 33% Bantu (proxied by isiXhosa), 16% European, 12% South Asian (Gujarati), and 8% East Asian (Chinese), highlighting methodological improvements in handling complex multi-way admixture over prior ranges of 23–65% African and 7–10% Asian reported in smaller datasets.[19] A 2025 genome-wide study of over 1,000 SAC individuals across 22 locations provided the most spatially resolved estimates, averaging 33.4% Khoe-San (range 12.0–69.0%), 22.5% Bantu/West African (7.6–39.5%), 21.7% European (9.2–40.5%), 12.1% South Asian (9.0–19.9% with minimal East Asian), 5.8% Malagasy, and under 3% East African (0.1–2.9%), with Khoisan predominant in 14 sites.[2] Regional gradients show elevated Khoisan inland and eastward, higher Bantu/West African in the east, and increased European and Asian components along the western coast, such as in Cape Town, reflecting localized slave imports and settler influences.[2] Admixture timing, inferred from haplotype lengths, aligns with Dutch colonial expansion (1650s–1700s) for European input and earlier Khoisan-Bantu contacts, while sex-biased patterns—male-skewed European and East African, female-skewed Khoisan—mirror historical asymmetries in colonial unions and enslavement.[2]| Ancestral Component | Average Proportion | Range Across Individuals/Sites |

|---|---|---|

| Khoe-San | 33.4% | 12.0–69.0% |

| Bantu/West African | 22.5% | 7.6–39.5% |

| European | 21.7% | 9.2–40.5% |

| South Asian | 12.1% | 9.0–19.9% |

| Malagasy | 5.8% | Not specified |

| East African | <3% | 0.1–2.9% |

Religious Composition

The Coloured population in South Africa is predominantly Christian, with Islam representing a significant minority affiliation primarily linked to historical Malay slave descendants. According to the 2022 national census conducted by Statistics South Africa, 91.7% of Coloured individuals reported Christianity as their religion, 6.9% identified as Muslim, 0.5% reported no religious affiliation, 0.4% adhered to other beliefs, 0.3% followed Traditional African religions, and 0.1% identified with Hinduism.[4] These figures reflect self-reported data from a population of approximately 5.3 million Coloured people, who constitute about 8.2% of South Africa's total populace.[4]| Religious Affiliation | Percentage (2022 Census) |

|---|---|

| Christianity | 91.7% |

| Islam | 6.9% |

| No religion | 0.5% |

| Other | 0.4% |

| Traditional African religions | 0.3% |

| Hinduism | 0.1% |

Historical Origins

Pre-Colonial Foundations and Early Settlement (Pre-1652 to 1700)

The Cape region prior to 1652 was inhabited by Khoisan peoples, comprising Khoikhoi pastoralists and San hunter-gatherers. Khoikhoi clans, such as the Goringhaiqua and Gorachouqua, practiced transhumant herding of sheep, goats, and cattle, establishing seasonal camps near water sources and engaging in limited trade with European ships that had visited Table Bay since the late 15th century.[22] These groups numbered in the thousands around the peninsula, with social structures organized around kinship and livestock ownership, which symbolized wealth and status.[23] San populations, often displaced or incorporated into Khoikhoi societies, relied on foraging and rock art traditions that evidenced their long presence in southern Africa dating back tens of thousands of years.[24] On April 6, 1652, Jan van Riebeeck arrived with three ships under the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to establish a refreshment station at Table Bay, aiming to supply passing vessels with fresh water, vegetables, and meat for the Asia trade route. Initial contacts with Khoikhoi leaders, including Autshumao, involved bartering copper, tobacco, and bread for cattle and sheep, establishing temporary economic interdependence.[25] However, as settlers expanded gardens and claimed land, tensions arose over resources, culminating in the First Khoikhoi-Dutch War (1659–1660), where Khoikhoi raided farms in response to encroachments.[26] Interpersonal relations between European men and Khoikhoi women began almost immediately, driven by the scarcity of European women among the roughly 100 initial settlers and cultural practices of concubinage. These unions produced the earliest mixed-ancestry offspring, laying the genetic foundation for the Cape Coloured population through Khoisan-European admixture estimated at 30–50% Khoisan in later studies tracing to this period.[27] Krotoa, a niece of Autshumao from the Goringhaiqua clan, exemplified this dynamic; taken into the Van Riebeeck household around 1652 at age 10–12, she learned Dutch, served as interpreter in trade negotiations, converted to Christianity in 1662 (baptized as Eva), and married VOC surgeon Pieter van Meerhof in 1664, bearing two children before his death in 1668.[28] Her role bridged communities but ended in exile and death in 1674, highlighting the precarious integration of early mixed individuals.[29] By 1700, the settlement population had grown to about 1,500 Europeans, with free burghers farming beyond the initial fort, while ongoing skirmishes like the Second Khoikhoi-Dutch War (1673–1677) reduced Khoikhoi autonomy and increased dependency through labor incorporation and intermarriage. Imported slaves from Southeast Asia and Madagascar from 1658 onward added layers of admixture, but the predominant early foundation remained Khoisan-European unions amid VOC-controlled expansion.[26] This era's demographic shifts, substantiated by historical records and subsequent genetic analyses, established the mixed heritage central to Cape Coloured origins without formalized racial categories until later.[25]Expansion of Admixture and Community Formation (1700-1900)

During the 18th century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) imported tens of thousands of slaves to the Cape Colony to support agricultural expansion and urban labor needs, with primary sources including Madagascar (about 25% of imports), Southeast Asia (Indonesia and Malaysia, around 26%), and East Africa (Mozambique region, approximately 25%).[30] By the 1710s, the slave population consistently exceeded the number of free European burghers, reaching roughly 6,700 slaves against 5,500 Europeans by 1754, while the Khoisan population had declined sharply due to smallpox epidemics and incorporation into servile labor systems.[26] This demographic shift facilitated broader admixture, as European male settlers, often in imbalanced sex ratios favoring men, formed unions—typically non-marital—with Khoisan women and imported female slaves, producing offspring of mixed European, Khoisan, and non-local African or Asian ancestry.[31] Such unions were driven by practical necessities and social norms in a frontier society, where formal marriages across racial lines were rare but concubinage and extramarital relations were common among VOC officials and farmers; children from these relationships were often acknowledged by fathers and manumitted, swelling the "free black" or "bastard" class of artisans, laborers, and smallholders concentrated in Cape Town and surrounding districts.[32] Manumission remained infrequent, averaging about 14 slaves freed annually in the 18th century, typically requiring payment of fees equivalent to the slave's value (often 100-200 rixdollars) and proof of self-support to avoid becoming a public burden.[33] By the late 1700s, this free mixed-ancestry group numbered in the thousands, forming autonomous communities with skills in trades like carpentry and masonry, distinct from both indentured Khoisan remnants and enslaved populations.[34] Under British administration after 1806, the slave trade ended in 1807, shifting reliance to locally born slaves and accelerating community consolidation through ongoing intermixing and the 1834 emancipation, which freed approximately 35,000-40,000 slaves but imposed a four-year apprenticeship period binding many to former owners.[35] Former slaves, predominantly of mixed descent by this era due to generational admixture, integrated into the emerging Coloured population, which grew to comprise about 40-50% non-European ancestry in urban centers by mid-century, supported by networks of mutual aid and occupations in fishing, portering, and domestic service.[36] By 1904, census records showed the Coloured population exceeding 100,000 in the Cape Colony, solidified as a creolized ethnic group with shared Afrikaans-based dialect, Christian or Muslim affiliations, and socioeconomic niches between white settlers and Bantu-speaking arrivals from the east.[31] This formation reflected causal dynamics of labor importation, demographic imbalances, and selective manumission rather than deliberate policy, yielding a population genetically averaging 30-40% European, 20-30% Khoisan, and the balance from slave ancestries by genetic reconstructions of historical patterns.[37]Classification and Marginalization Under Segregation (1900-1948)