Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wrist

View on WikipediaThis article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (June 2015) |

| Wrist | |

|---|---|

A human showing the wrist in the centre | |

The carpal bones, sometimes included in the definition of the wrist | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | articulatio radiocarpalis |

| MeSH | D014953 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.026 |

| TA2 | 147 |

| FMA | 24922 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In human anatomy, the wrist is variously defined as (1) the carpus or carpal bones, the complex of eight bones forming the proximal skeletal segment of the hand;[1][2] (2) the wrist joint or radiocarpal joint, the joint between the radius and the carpus[2] and; (3) the anatomical region surrounding the carpus including the distal parts of the bones of the forearm and the proximal parts of the metacarpus or five metacarpal bones and the series of joints between these bones, thus referred to as wrist joints.[3][4] This region also includes the carpal tunnel, the anatomical snuff box, bracelet lines, the flexor retinaculum, and the extensor retinaculum.

As a consequence of these various definitions, fractures to the carpal bones are referred to as carpal fractures, while fractures such as distal radius fracture are often considered fractures to the wrist.

Structure

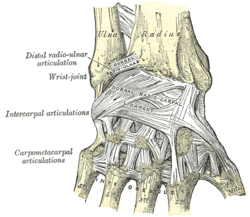

[edit]The distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) is a pivot joint located between the distal ends of the radius and ulna, which make up the forearm. Formed by the head of the ulna (the bony knob on the back of the wrist) and the ulnar notch of the radius, the DRUJ is separated from the radiocarpal (wrist) joint by an articular disk lying between the radius and the styloid process of the ulna. The capsule of the joint is lax and extends from the inferior sacciform recess to the ulnar shaft. The DRUJ works with the proximal radioulnar joint (at the elbow) for pronation and supination.[5]

The radiocarpal (wrist) joint is an ellipsoid joint formed by the radius and the articular disc proximally and the proximal row of carpal bones distally. The carpal bones on the ulnar side only make intermittent contact with the proximal side — the triquetrum only makes contact during ulnar abduction. The capsule, lax and un-branched, is thin on the dorsal side and can contain synovial folds. The capsule is continuous with the midcarpal joint and strengthened by numerous ligaments, including the palmar and dorsal radiocarpal ligaments, and the ulnar and radial collateral ligaments. [6]

The parts forming the radiocarpal joint are the lower end of the radius and under surface of the articular disk above; and the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetral bones below. The articular surface of the radius and the undersurface of the articular disk form together with a transversely elliptical concave surface, the receiving cavity. The superior articular surfaces of the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum form a smooth convex surface, the condyle, which is received into the concavity.[7]

Carpal bones of the hand:

- Proximal: A=Scaphoid, B=Lunate, C=Triquetrum, D=Pisiform

- Distal: E=Trapezium, F=Trapezoid, G=Capitate, H=Hamate

In the hand proper a total of 13 bones form part of the wrist: eight carpal bones—scaphoid, lunate, triquetral, pisiform, trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate— and five metacarpal bones—the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth metacarpal bones.[8]

The midcarpal joint is the S-shaped joint space separating the proximal and distal rows of carpal bones. The intercarpal joints, between the bones of each row, are strengthened by the radiate carpal and pisohamate ligaments and the palmar, interosseous, and dorsal intercarpal ligaments. Some degree of mobility is possible between the bones of the proximal row while the bones of the distal row are connected to each other and to the metacarpal bones —at the carpometacarpal joints— by strong ligaments —the pisometacarpal and palmar and dorsal carpometacarpal ligament— that makes a functional entity of these bones. Additionally, the joints between the bases of the metacarpal bones —the intermetacarpal articulations— are strengthened by dorsal, interosseous, and palmar intermetacarpal ligaments.[6]

The earliest carpal bones to ossify are capitate bone and hamate bone in the first six months of an infant life.[9]

Articulations

[edit]The radiocarpal, intercarpal, midcarpal, carpometacarpal, and intermetacarpal joints often intercommunicate through a common synovial cavity. [10]

Articular surfaces

[edit]It has two articular surfaces named, proximal and distal articular surfaces respectively. The proximal articular surface is made up of the lower end of the radius and a triangular articular disc of the inferior radio-ulnar joint. On the other hand, the distal articular surface is made up of proximal surfaces of the scaphoid, triquetral and lunate bones.[11]

Function

[edit]Movement

[edit]The extrinsic hand muscles are located in the forearm where their bellies form the proximal fleshy roundness. When contracted, most of the tendons of these muscles are prevented from standing up like taut bowstrings around the wrist by passing under the flexor retinaculum on the palmar side and the extensor retinaculum on the dorsal side. On the palmar side the carpal bones form the carpal tunnel,[12] through which some of the flexor tendons pass in tendon sheaths that enable them to slide back and forth through the narrow passageway (see carpal tunnel syndrome).[13]

Starting from the mid-position of the hand, the movements permitted in the wrist proper are (muscles in order of importance):[14][15]

- Marginal movements: radial deviation (abduction, movement towards the thumb) and ulnar deviation (adduction, movement towards the little finger). These movements take place about a dorsopalmar axis (back to front) at the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints passing through the capitate bone.

- Radial abduction (up to 20°):[16] extensor carpi radialis longus, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus, flexor carpi radialis, flexor pollicis longus

- Ulnar adduction (up to 30°):[16] extensor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi

- Movements in the plane of the hand: flexion (palmar flexion, tilting towards the palm) and extension (dorsiflexion, tilting towards the back of the hand). These movements take place through a transverse axis passing through the capitate bone. Palmar flexion is the most powerful of these movements because the flexors, especially the finger flexors, are considerably stronger than the extensors.

- Extension (up to 60°):[16] extensor digitorum, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor indicis, extensor pollicis longus, extensor digiti minimi, extensor carpi ulnaris

- Palmar flexion (up to 70°):[16] flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor digitorum profundus, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor pollicis longus, flexor carpi radialis, abductor pollicis longus

- Intermediate or combined movements

However, movements at the wrist can not be properly described without including movements in the distal radioulnar joint in which the rotary actions of supination and pronation occur and this joint is therefore normally regarded as part of the wrist.[17]

Clinical significance

[edit]

Wrist pain has a number of causes, including carpal tunnel syndrome,[16] ganglion cyst,[19] tendinitis,[20] and osteoarthritis. Tests such as Phalen's test involve palmarflexion at the wrist.

The hand may deviate at the wrist in some conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Ossification of the bones around the wrist is one indicator used in taking a bone age.

A wrist fracture typically refers to a distal radius fracture. It is more common in non-Hispanic women and is associated with factors such as alcohol consumption, smoking, high serum phosphate levels, osteoporosis, and obesity.[21]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The English word "wrist" is etymologically derived from the Proto-Germanic word wristiz from which are derived modern German Rist ("instep", "wrist") and modern Swedish vrist ("instep", "ankle"). The base writh- and its variants are associated with Old English words "wreath", "wrest", and "writhe". The wr- sound of this base seems originally to have been symbolic of the action of twisting.[22]

See also

[edit]- Brunelli procedure, related to instability in the wrist, caused by a torn scapholunate ligament.

- Knuckle-walking, a kind of quadrupedal locomotion involving wrist bone specialization

- Wristlocks use movement extremes of the wrist for martial applications.

- Glossary of bowling § Wrist, a measure of wrist position in bowling ball deliveries

Additional images

[edit]-

Wrist joint. Deep dissection. Posterior view.

-

Wrist joint. Deep dissection. Posterior view.

-

Wrist joint. Deep dissection. Anterior, palmar, view.

-

Wrist joint. Deep dissection. Anterior, palmar, view.

References

[edit]- ^ Behnke 2006, p. 76 "The wrist contains eight bones, roughly aligned in two rows, known as the carpal bones."

- ^ a b Moore KL, Agur AM (2006). Essential clinical anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 485. ISBN 0-7817-6274-X.

The wrist (carpus), the proximal segment of the hand, is a complex of eight carpal bones. The carpus articulates proximally with the forearm at the wrist joint and distally with the five metacarpals. The joints formed by the carpus include the wrist (the radiocarpal joint), intercarpal, carpometacarpal, and intermetacarpal joints. Augmenting movement at the wrist joint, the rows of carpals glide on each other [...]

- ^ Behnke 2006, p. 77 "With the large number of bones composing the wrist (ulna, radius, eight carpas, and five metacarpals), it makes sense that there are many, many joints that make up the structure known as the wrist."

- ^ Baratz M, Watson AD, Imbriglia JE (1999). Orthopaedic surgery: the essentials. Thieme. p. 391. ISBN 0-86577-779-9.

The wrist joint is composed of not only the radiocarpal and distal radioulnar joints but also the intercarpal articulations.

- ^ Platzer 2004, p. 122

- ^ a b Platzer 2004, p. 130

- ^ "Wrist Joint". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ Platzer 2004, pp. 126–129

- ^ Al-Khater KM, Hegazi TM, Al-Thani HF, Al-Muhanna HT, Al-Hamad BW, Alhuraysi SM, et al. (September 2020). "Time of appearance of ossification centers in carpal bones. A radiological retrospective study on Saudi children". Saudi Medical Journal. 41 (9): 938–946. doi:10.15537/smj.2020.9.25348. PMC 7557557. PMID 32893275.

- ^ Isenberg DA, Maddison P, Woo P (2004). Oxford textbook of rheumatology. Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-19-850948-0.

- ^ "Wrist Joint". Earth's Lab. 8 August 2018.

- ^ Rea P (2016-01-01). "Chapter 3 - Neck". In Rea P (ed.). Essential Clinically Applied Anatomy of the Peripheral Nervous System in the Head and Neck. Academic Press. pp. 131–183. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-803633-4.00003-x. ISBN 978-0-12-803633-4.

- ^ Saladin KS (2003). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 361, 365.

- ^ Platzer 2004, p. 132

- ^ Platzer 2004, p. 172

- ^ a b c d e Lalani I, Argoff CE (2008-01-01). "Chapter 10 - History and Physical Examination of the Pain Patient". In Benzon HT, Rathmell JP, Wu CL, Turk DC (eds.). Raj's Practical Management of Pain (Fourth ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby. pp. 177–188. doi:10.1016/B978-032304184-3.50013-3. ISBN 978-0-323-04184-3.

- ^ Kingston B (2000). Understanding joints: a practical guide to their structure and function. Nelson Thornes. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-7487-5399-0.

- ^ Döring AC, Overbeek CL, Teunis T, Becker SJ, Ring D (October 2016). "A Slightly Dorsally Tilted Lunate on MRI can be Considered Normal". The Archives of Bone and Joint Surgery. 4 (4): 348–352. PMC 5100451. PMID 27847848.

- ^ Stretanski MF (2020-01-01). "Chapter 32 - Hand and Wrist Ganglia". In Frontera WR, Silver JK, Rizzo TD (eds.). Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (Fourth ed.). Philadelphia: Content Repository Only!. pp. 169–173. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-54947-9.00032-8. ISBN 978-0-323-54947-9. S2CID 229189365.

- ^ Waldman SD (2014-01-01). "Chapter 58 - Flexor Carpi Radialis Tendinitis". In Waldman SD (ed.). Atlas of Uncommon Pain Syndromes (Third ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 172–174. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4557-0999-1.00058-7. ISBN 978-1-4557-0999-1.

- ^ Ye, Juncai; Li, Qiao; Nie, Jing (2022-04-25). "Prevalence, Characteristics, and Associated Risk Factors of Wrist Fractures in Americans Above 50: The Cross-Sectional NHANES Study". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 13 800129. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.800129. ISSN 1664-2392. PMC 9082306. PMID 35547001.

- ^ "Hand Etymology". American Society for Surgery of the Hand.

Sources

[edit]- Behnke RS (2006). Kinetic anatomy. Human Kinetics. ISBN 0-7360-5909-1.

- Platzer W (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

External links

[edit]Wrist

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Bones

The wrist's skeletal framework is primarily composed of eight carpal bones, arranged in two transverse rows that form a flexible yet stable link between the forearm and hand.[4] The proximal row, positioned closest to the forearm, consists of four bones from the radial (lateral) to ulnar (medial) side: the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform.[4] The distal row includes the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate, also oriented from radial to ulnar.[4] These bones exhibit distinct shapes adapted to their roles in load transmission and mobility: the scaphoid is boat-shaped and lies in the floor of the anatomical snuffbox; the lunate is crescent- or moon-shaped; the triquetrum is pyramidal with three facets; and the pisiform is a small, pea-shaped sesamoid bone embedded in the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon.[5] In the distal row, the trapezium has a saddle-shaped surface for thumb articulation; the trapezoid is wedge-shaped; the capitate, the largest carpal, features a rounded head; and the hamate possesses a hook-like process (hamulus) on its palmar surface.[5][4] The carpal bones articulate with one another via intercarpal joints, creating a series of synovial interfaces that allow gliding motions, and they connect proximally to the distal ends of the radius and ulna.[4] Specifically, the scaphoid and lunate articulate directly with the distal radius to form the radiocarpal joint, while the ulna does not directly contact the carpals; instead, stability on the ulnar side is maintained by the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC), a cartilaginous disc and ligamentous structure that cushions the ulnar head and binds it to the triquetrum and lunate.[4][6] The TFCC enhances wrist stability by distributing compressive forces and limiting excessive translation between the radius and ulna during forearm rotation.[6] Distally, the carpal bones transition to the hand via the five metacarpal bones, whose concave bases articulate with the distal row carpals to form carpometacarpal joints, providing a stable base for finger movements.[7] The overall arrangement of the carpals forms a concave arch on the palmar side, with the proximal and distal rows curving to create the carpal tunnel, an osteofibrous canal bounded by the carpal bones inferiorly and the flexor retinaculum superiorly, through which the median nerve and flexor tendons pass.[7]Joints

The wrist comprises several synovial joints that facilitate its complex mobility. The primary joints include the radiocarpal joint, an ellipsoid synovial joint formed by the articulation between the distal radius and the proximal row of carpal bones; the ulnocarpal joint, a plane synovial joint involving the ulna and the proximal carpals via the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC); the midcarpal joint, a double plane synovial joint between the proximal and distal rows of carpal bones; and the carpometacarpal joints, which consist of a saddle synovial joint at the thumb (first carpometacarpal) and plane synovial joints for the other four digits.[8][9][10][11] The articular surfaces of these joints exhibit specific morphologies to enable smooth interaction. In the radiocarpal joint, the concave distal radius articulates with the convex surfaces of the proximal carpal bones, while the ulnocarpal joint features relatively flat surfaces between the ulnar head, the TFCC disc, and the lunate and triquetrum. The midcarpal joint involves gliding between the convex distal aspects of the proximal carpals and the concave proximal aspects of the distal carpals, and the carpometacarpal joints display saddle-shaped (thumb) or plane configurations between distal carpals and metacarpal bases. Incongruencies in these surfaces, particularly at the radiocarpal and ulnocarpal interfaces, are compensated by the fibrocartilage of the TFCC, which provides a smooth, congruent articulating surface and load distribution.[8][9][12] Each wrist joint is enclosed by a capsule consisting of an outer fibrous layer for structural integrity and an inner synovial layer that secretes lubricating fluid. The capsules attach proximally to the radius and ulna and distally to the carpals, with volar (palmar) aspects being thicker and more reinforced for stability during load-bearing, while dorsal aspects are relatively thinner but contribute to overall containment. These capsules form continuous compartments around the synovial joints, preventing excessive translation.[13][2] Functionally, the wrist joints are divided into proximal and distal compartments to optimize motion distribution. The proximal compartment encompasses the radiocarpal and intercarpal joints, which primarily handle flexion-extension and deviation, while the distal compartment includes the midcarpal and carpometacarpal joints, facilitating finer adjustments and rotation. This division allows for coordinated, multi-planar movement across the wrist complex.[12][14]Ligaments and tendons

The wrist's stability and motion transmission rely on a network of ligaments and tendons that interconnect the carpal bones, radius, and ulna while facilitating the passage of muscle tendons from the forearm to the hand. Intrinsic ligaments connect adjacent carpal bones within the carpus, providing intercarpal stability, whereas extrinsic ligaments link the carpus to the forearm bones, offering broader joint reinforcement. Tendons of the flexor and extensor muscles traverse the wrist under specialized retinacula, which prevent tendon displacement and maintain mechanical efficiency during movement.[15][16] Intrinsic ligaments, situated entirely between carpal bones, are crucial for maintaining the alignment and stability of the proximal and distal carpal rows. The scapholunate ligament, a C-shaped structure connecting the scaphoid and lunate, features a thick dorsal component that acts as the primary stabilizer against shear forces, preventing scaphoid dissociation from the lunate. The lunotriquetral ligament, horseshoe-shaped and linking the lunate to the triquetrum, has its thickest palmar portion resisting rotational instability, thus preserving the integrity of the proximal carpal row during wrist motion. These ligaments collectively inhibit excessive intercarpal translation and rotation, ensuring coordinated carpal kinematics.[15][17][16] Extrinsic ligaments extend from the radius and ulna to the carpal bones, serving as key stabilizers of the radiocarpal and ulnocarpal joints. The radiocarpal ligaments include the palmar radioscaphocapitate ligament, which originates from the anterolateral radius and inserts into the capitate, forming a supportive sling for scaphoid rotation and overall wrist stability. Dorsal radiocarpal ligaments arise from the dorsal radius and insert into the triquetrum and lunate, countering volar translation. The ulnocarpal complex comprises the ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral ligaments, which originate from the volar radioulnar ligament and attach to the lunate and triquetrum, respectively, providing ulnar-sided support against varus forces. These extrinsic structures, particularly the radioscaphocapitate, are essential for preventing carpal subluxation and load distribution across the wrist.[15][18][16] Flexor tendons pass through the volar aspect of the wrist beneath the flexor retinaculum, also known as the transverse carpal ligament, which forms the roof of the carpal tunnel. This retinaculum, a fibrous band approximately 3 cm long and 2.5 cm wide, attaches laterally to the scaphoid tuberosity and trapezial ridge and medially to the pisiform and hamate hook, enclosing nine tendons—the four flexor digitorum superficialis, four flexor digitorum profundus, and one flexor pollicis longus—along with their synovial sheaths. These sheaths reduce friction during tendon gliding, while the retinaculum functions as a pulley to enhance flexor efficiency and prevent bowstringing, where tendons would otherwise displace volarly under tension.[19][20] Extensor tendons course dorsally through six discrete compartments formed by fibrous septa beneath the extensor retinaculum, a broad oblique ligamentous sheet that maintains dorsal alignment. The retinaculum attaches proximally to the distal radius near the styloid process and distally to the pisiform and triquetrum, without direct ulnar attachment to allow supination flexibility. The compartments house specific tendons: the first contains abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis; the second, extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis; the third, extensor pollicis longus; the fourth, extensor digitorum and indicis; the fifth, extensor digiti minimi; and the sixth, extensor carpi ulnaris. Each compartment is lined by a synovial sheath that lubricates tendon movement, with the retinaculum preventing bowstringing by holding tendons close to the bone axis during extension.[21][22][23]Muscles

The muscles acting on the wrist are divided into extrinsic and intrinsic groups, with the extrinsic muscles originating in the forearm and providing the primary force for wrist movements through long tendons, while the intrinsic muscles, located within the hand, offer finer control and supplementary stability.[24]Extrinsic Muscles

The extrinsic muscles are responsible for the major motions of wrist flexion, extension, radial deviation, and ulnar deviation. The forearm flexors include the flexor carpi radialis, which originates from the medial epicondyle of the humerus and inserts at the base of the second metacarpal, primarily acting to flex and abduct the wrist; the flexor carpi ulnaris, originating from the medial epicondyle and olecranon of the ulna and inserting into the pisiform, hook of the hamate, and base of the fifth metacarpal, which flexes and adducts the wrist; and the palmaris longus, originating from the medial epicondyle and inserting into the palmar aponeurosis and flexor retinaculum, aiding in wrist flexion.[24] The forearm extensors comprise the extensor carpi radialis longus, originating from the lateral supracondylar ridge of the humerus and inserting at the base of the second metacarpal, which extends and abducts the wrist; the extensor carpi radialis brevis, originating from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and inserting at the base of the third metacarpal, also extending and abducting the wrist; and the extensor carpi ulnaris, originating from the lateral epicondyle and posterior border of the ulna and inserting at the base of the fifth metacarpal, which extends and adducts the wrist.[24]| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Primary Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexor carpi radialis | Medial epicondyle of humerus | Base of 2nd metacarpal | Flexion and abduction of wrist |

| Flexor carpi ulnaris | Medial epicondyle, olecranon | Pisiform, hook of hamate, 5th metacarpal base | Flexion and adduction of wrist |

| Palmaris longus | Medial epicondyle of humerus | Palmar aponeurosis, flexor retinaculum | Flexion of wrist |

| Extensor carpi radialis longus | Lateral supracondylar ridge of humerus | Base of 2nd metacarpal | Extension and abduction of wrist |

| Extensor carpi radialis brevis | Lateral epicondyle of humerus | Base of 3rd metacarpal | Extension and abduction of wrist |

| Extensor carpi ulnaris | Lateral epicondyle, ulna | Base of 5th metacarpal | Extension and adduction of wrist |

Intrinsic Muscles

The intrinsic muscles of the hand, including the thenar and hypothenar groups, play a secondary role in wrist function by providing stability through their attachments to carpal bones and the flexor retinaculum. The thenar muscles at the base of the thumb—such as the abductor pollicis brevis (originating from the scaphoid and trapezium, inserting on the proximal phalanx of the thumb), opponens pollicis (originating from the trapezium, inserting on the first metacarpal), and flexor pollicis brevis (originating from the trapezium and flexor retinaculum, inserting on the proximal phalanx of the thumb)—contribute to wrist stability by anchoring thumb opposition and counterbalancing forces on the radial side of the wrist.[25] Similarly, the hypothenar muscles at the base of the little finger—abductor digiti minimi (originating from the pisiform, inserting on the proximal phalanx of the fifth digit), flexor digiti minimi brevis (originating from the hamate and flexor retinaculum, inserting on the proximal phalanx of the fifth digit), and opponens digiti minimi (originating from the flexor retinaculum, inserting on the fifth metacarpal)—enhance ulnar-side stability by supporting the pisiform and retinaculum during grip activities.[25]Synergistic Actions

The extrinsic forearm muscles enable wrist motion through their long tendons that cross the wrist joint, allowing coordinated flexion and extension while the radial and ulnar pairs oppose each other in deviation to maintain balanced movement.[24] These actions are supported by basic innervation from the median nerve (flexor carpi radialis and palmaris longus), ulnar nerve (flexor carpi ulnaris and hypothenar muscles), and radial nerve (extensors and some thenar components).[24][25]Comparative Anatomy

In humans, the wrist muscles are adapted for precision grip, featuring a more mobile thumb with enlarged intrinsic thenar muscles and enhanced extrinsic flexors like the flexor pollicis longus for fine manipulation and power grips during tool use.[26] In contrast, quadrupedal primates such as chimpanzees have wrist muscles optimized for locomotion, with restricted extension, smaller intrinsic muscles, and elongated curved fingers suited for hook grips in arboreal suspension rather than precise opposition.[26]Nerves and blood supply

The wrist is innervated primarily by the median, ulnar, and radial nerves, which provide both sensory and motor functions to the hand and forearm structures. The median nerve, formed by contributions from the lateral and medial cords of the brachial plexus (C5-T1 roots), enters the wrist through the carpal tunnel, a fibro-osseous passageway bounded by the carpal bones and flexor retinaculum.[27] Within the carpal tunnel, it lies superficial to the flexor tendons and gives off motor branches, including the recurrent motor branch, which innervates the thenar muscles such as the abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis (superficial head), and opponens pollicis.[27] Sensory branches emerge distal to the tunnel, supplying the palmar aspect of the thumb, index finger, middle finger, and radial half of the ring finger, while the palmar cutaneous branch arises proximal to the tunnel to innervate the proximal lateral palm.[27] The ulnar nerve (C8-T1 roots, with occasional C7 contribution), arising from the medial cord of the brachial plexus, courses along the medial forearm and enters the wrist through Guyon's canal, a fibro-osseous tunnel approximately 40-45 mm long, bounded by the pisiform bone medially, the hook of the hamate laterally, the volar carpal ligament superiorly, and the transverse carpal ligament and pisohamate ligament inferiorly.[28][29] In Guyon's canal, the ulnar nerve and artery travel together, and distal to the canal, the nerve bifurcates (in 66-86% of cases) into superficial (sensory) and deep (motor) branches; the superficial branch provides sensation to the palmar and dorsal aspects of the little finger and ulnar half of the ring finger, while the deep branch innervates the hypothenar muscles, interossei, adductor pollicis, and the third and fourth lumbricals.[28][29] The radial nerve (C5-T1 roots), originating from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, contributes minimally to wrist motor function but provides sensory innervation via its superficial branch. This branch emerges in the distal forearm, travels deep to the brachioradialis tendon, and crosses the anatomical snuffbox at the wrist, becoming subcutaneous to supply sensation to the dorsal aspect of the lateral three-and-a-half digits (proximal phalanges) and the dorsolateral wrist and hand.[30] It is purely sensory at this level and lacks motor branches to wrist intrinsics.[30] The arterial blood supply to the wrist and hand derives mainly from the radial and ulnar arteries, terminal branches of the brachial artery, forming interconnected palmar arches for redundancy. The radial artery passes laterally over the wrist through the anatomical snuffbox, giving off the superficial palmar branch that anastomoses with the ulnar artery to form the superficial palmar arch, which lies superficial to the long flexor tendons and deep to the palmar aponeurosis, supplying the palmar digital arteries to the fingers.[31][32] The deep palmar arch is primarily formed by the radial artery's continuation, joined by the deep branch of the ulnar artery after it traverses Guyon's canal, and lies deep to the flexor tendons, providing branches to the palmar metacarpal arteries that interconnect with the superficial arch.[31] Key anastomoses occur between the radial and ulnar systems at the wrist, including the dorsal carpal arch (formed by dorsal branches of both arteries) and palmar metacarpal connections, ensuring collateral circulation.[32] Venous drainage of the wrist follows the arterial pattern, with superficial veins forming the dorsal venous network over the wrist and hand, which drains laterally into the cephalic vein and medially into the basilic vein; these ascend the forearm to join the axillary vein.[32] Deep veins accompany the arteries, forming palmar venous arches that connect to the dorsal network.[31] Lymphatic drainage from the wrist and hand occurs via superficial and deep pathways to the cubital (epitrochlear or supratrochlear) nodes at the medial elbow, located 4-5 cm above the humeral epitrochlea in the superficial fascia.[33] Superficial lymphatics from the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the hand and wrist drain primarily to these 1-3 cubital nodes, which in turn connect to axillary nodes; deep lymphatics follow the neurovascular bundles along tendons and joints to the same cubital nodes before proceeding centrally.[33] The neurovascular bundles at the wrist are clinically significant due to their confined spaces, predisposing to compression; for instance, the median nerve in the carpal tunnel is vulnerable to pressure increases (e.g., 20-30 mmHg) from synovial swelling or repetitive flexion, potentially impairing blood flow and causing ischemia.[34] Similarly, the ulnar nerve in Guyon's canal can be compressed in three zones—proximal (mixed deficits), deep motor branch (motor only), or superficial sensory—often due to anatomical variations like aberrant muscles, leading to localized sensory or motor impairment.[29]Function

Movements

The wrist joint complex enables a variety of movements essential for hand function, primarily occurring at the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints. These include flexion, extension, radial deviation (abduction), ulnar deviation (adduction), and circumduction, which is a circular motion resulting from the sequential combination of these primary movements.[2][35] The normal range of wrist flexion is approximately 70-80 degrees, allowing the palm to move toward the anterior forearm, while extension reaches about 70 degrees, directing the back of the hand posteriorly. Radial deviation typically measures 20 degrees, moving the hand toward the thumb side, and ulnar deviation ranges from 30-40 degrees, shifting the hand toward the little finger side. These ranges can vary slightly based on individual anatomy and measurement techniques.[36][35][37] In addition to isolated movements, the wrist exhibits coupled motions that integrate flexion-extension with radial-ulnar deviation, such as the dart-thrower's motion. This functional plane extends from radial extension to ulnar flexion and is prominent in daily activities like throwing or pouring, optimizing stability and efficiency.[38][39] Flexion and extension primarily occur at the radiocarpal joint, which connects the radius to the proximal carpal row, while radial and ulnar deviation are predominantly facilitated by the midcarpal joint between the proximal and distal carpal rows.[40][39][35] Factors influencing the wrist's range of motion include age, with reductions observed in older adults due to tissue degeneration; sex, where females often exhibit greater flexibility; ligament laxity, which can increase mobility but risk instability; and measurement methods like goniometry, which standardize assessment using an inclinometer or protractor for precision.[41][42][43]Biomechanics

The biomechanics of the wrist involves efficient load transmission across its complex carpal architecture to support hand function while maintaining stability. In neutral position, approximately 80% of axial compressive forces are transmitted through the radiocarpal joint via the scaphoid and lunate to the distal carpal row, with the remaining 20% passing through the ulnocarpal joint primarily involving the triquetrum.[16] This distribution ensures balanced force handling during weight-bearing activities, but variations in ulnar variance significantly alter it; positive ulnar variance (ulna longer than radius) increases ulnar-sided loading to about 42%, while negative variance reduces it to roughly 3-5%, potentially leading to uneven stress on carpal structures. Wrist stability relies on a combination of ligamentous tension, muscular co-contraction, and joint surface congruence to resist shear and translational forces. Intrinsic ligaments, such as the scapholunate interosseous ligament, maintain alignment between the scaphoid and lunate under tension, preventing scapholunate dissociation that can result in dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) with scaphoid palmar flexion and lunate dorsal extension.[45] Extrinsic ligaments like the radioscaphocapitate further constrain excessive motion, while joint congruence from the ellipsoidal radial surfaces and reciprocal carpal shapes provides passive resistance to dislocation. Muscle co-contraction, particularly of radial wrist stabilizers such as the extensor carpi radialis longus and abductor pollicis longus, actively reduces scapholunate gapping and restores proximal row alignment in cases of ligament compromise, whereas ulnar deviators like the extensor carpi ulnaris may exacerbate instability if imbalanced.[46] Kinematic models describe wrist motion through instantaneous centers of rotation (ICRs), which shift dynamically to accommodate multiplanar movements. During flexion-extension, ICRs are located near the capitate head, allowing the proximal carpal row to act as an intercalated segment linking the radius and distal row in a coordinated arc of approximately 120-140 degrees.[47] The dart-thrower's arc, an oblique plane from radial extension to ulnar flexion spanning about 120 degrees, features relatively stationary proximal row motion with primary rotation at the midcarpal joint, enhancing stability for functional tasks like throwing or pouring.[38] In occupational settings, repetitive wrist tasks involving sustained force vectors—such as axial compression, radial/ulnar deviation, and palmar flexion—contribute to biomechanical overload and repetitive strain injuries. High-force gripping combined with awkward postures, as seen in assembly line work or tool use, amplifies shear stresses on the carpus, increasing risk of ligament attenuation and tendinopathy without adequate recovery periods.[48]Development

Embryonic formation

The development of the wrist begins with the formation of the upper limb bud around day 26 of human embryonic gestation, arising from mesenchymal cells in the lateral plate mesoderm that protrude and become encased by ectoderm.[49] This bud's proximal-distal axis is primarily directed by the apical ectodermal ridge (AER), a thickened ectodermal structure at the distal tip that secretes fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), such as FGF8 and FGF10, to promote outgrowth and maintain undifferentiated mesenchymal cells in the underlying progress zone.[49] Concurrently, the anterior-posterior axis is patterned by the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA), located in the posterior mesenchyme of the limb bud, which expresses Sonic hedgehog (Shh) to establish digit identity and radial-ulnar polarity, with disruptions leading to mirror-image duplications or deficiencies.[49] By weeks 4 to 6 of gestation, mesenchymal cells within the distal autopod region undergo condensation to form cartilaginous precursors of the carpal bones, marking the initial skeletal anlage of the wrist; this process is evident as early chondrified structures identifiable around 8 weeks gestational age.[49][50] These condensations, regulated by bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and the transcription factor SOX9, create the hyaline cartilage models that prefigure the eight carpal bones, with the hand plate emerging and a wrist constriction appearing to delineate the carpus from the forearm.[49] Genetic regulation of carpal patterning involves Hox genes from the HOXA and HOXD clusters, which are expressed in nested domains along the proximal-distal axis to specify skeletal elements, including the zeugopod-autopod transition critical for wrist formation; for instance, HOXD13 mutations can alter carpal morphology.[49] Wnt signaling pathways complement this by influencing dorso-ventral polarity and Shh expression in the ZPA, with Wnt7a from the dorsal ectoderm inducing LMX1 to dorsalize the limb and support proper carpal alignment.[49] Embryonic anomalies of the wrist, such as radial dysplasia, often originate from failures in mesenchymal segmentation or formation during these early limb bud stages, potentially due to disruptions in Shh signaling or mesodermal development, resulting in underdevelopment of the radius and radial carpal bones.[51]Ossification

The ossification of the carpal bones in the wrist follows a predictable postnatal sequence, beginning with the appearance of primary ossification centers shortly after birth and progressing through mineralization and eventual fusion with adjacent bones by late adolescence. The capitate and hamate are the first to ossify, typically between 1 and 3 months of age, followed by the triquetrum at 2 to 3 years, the lunate at 3 to 4 years, the trapezium and trapezoid at 4 to 5 years, the scaphoid at 4 to 6 years, and the pisiform at 8 to 12 years as a sesamoid bone.[52][53] Full skeletal maturity in the wrist is achieved with the fusion of these centers to the epiphyses of the radius and ulna, generally by 16 to 18 years in females and 18 to 20 years in males.[54] Sex differences influence this timeline, with females typically exhibiting ossification 1 to 2 years earlier than males across most carpal bones, a pattern attributed to hormonal influences on skeletal maturation.[55] Ethnic variations also contribute to timing differences; for instance, children of African descent often show advanced ossification compared to those of European or Asian descent, with bone age exceeding chronological age by several months in some populations.[56] A 2020 radiological study on Saudi children highlighted population-specific variability, noting earlier ossification of most carpal bones relative to Indian cohorts, underscoring the role of genetic and environmental factors in these discrepancies.[53] The Greulich-Pyle atlas, developed from radiographic standards of hand and wrist development, serves as a key tool for assessing bone age in clinical and forensic contexts, comparing patient radiographs to reference images to evaluate maturation against chronological age.[57] This method is widely used in endocrinology to diagnose growth disorders and in forensics for age estimation, providing a baseline for identifying deviations influenced by factors such as nutrition, which recent research indicates can accelerate or delay ossification timing by altering metabolic processes.[58] For example, nutritional deficiencies may retard carpal ossification, while adequate intake supports adherence to standard timelines.[58]Clinical significance

Injuries

The wrist is susceptible to a variety of traumatic injuries, primarily due to its role in weight-bearing and impact absorption during falls. Among these, fractures of the distal radius are the most common, accounting for approximately 20% of all skeletal fractures.[59] These fractures exhibit an overall incidence of 207.8 per 100,000 persons per year, with females experiencing a higher rate of 323.4 per 100,000 per year.[60] Colles' fractures, characterized by dorsal angulation and displacement of the distal fragment, typically result from a fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH) with the wrist in dorsiflexion, leading to tension on the volar aspect and compression dorsally.[61] In contrast, Smith's fractures involve volar displacement and angulation, often from a fall on a flexed wrist or direct volar impact, representing the reverse mechanism of Colles' fractures.[62] These injuries are particularly prevalent in postmenopausal women due to accelerated bone loss at the distal radius associated with menopause.[63] Scaphoid fractures, which comprise about 60-70% of carpal bone injuries, often occur from FOOSH or axial loading with wrist hyperextension and radial deviation, with an incidence of approximately 1.47 fractures per 100,000 persons in the United States.[64] A major concern with these fractures is the risk of avascular necrosis (AVN), stemming from the scaphoid's retrograde blood supply, which is particularly vulnerable in proximal pole fractures (up to 100% risk) and waist fractures (around 33% risk), with overall AVN rates of 5-10% following immobilization and higher for proximal lesions.[65][66] Ligamentous injuries frequently accompany high-energy trauma to the wrist. Scapholunate dissociation arises from axial loading and extension, such as in FOOSH, disrupting the scapholunate interosseous ligament and leading to carpal instability if untreated.[67] Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tears commonly result from falls on the outstretched or ulnarly deviated wrist, or rotational twists, causing ulnar-sided pain and potential instability.[68] Soft tissue traumas include tendon ruptures and contusions. The extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon is prone to rupture near Lister's tubercle, often as a delayed complication of distal radius fractures due to sharp bony edges or ischemia, though spontaneous cases can occur from severe sprains with hematoma formation.[69][70] Contusions to wrist soft tissues, such as from direct blows, result in localized swelling and ecchymosis, potentially impairing mobility without structural disruption.[71] Acute management of wrist injuries emphasizes prompt stabilization to prevent further damage. Immobilization with splints or casts is standard for fractures and sprains to maintain alignment, while initial imaging via X-rays assesses bony integrity in multiple views; MRI is indicated for suspected soft tissue or ligamentous involvement to evaluate tears or occult fractures.[72] Complications such as compartment syndrome, marked by disproportionate pain worsening with passive stretch, require urgent fasciotomy to avert irreversible muscle and nerve damage, occurring in up to 10% of severe forearm traumas.[73]Disorders

The wrist is susceptible to various non-traumatic pathological conditions that can impair function and cause chronic pain. Compressive neuropathies, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, involve entrapment of the median nerve within the carpal tunnel, leading to symptoms including numbness, tingling, and weakness in the thumb, index, middle, and part of the ring finger.[74] This condition arises from increased pressure on the nerve, often due to repetitive wrist motions, anatomical variations, or systemic factors like obesity and pregnancy.[75] Risk factors include female sex, women are three times more likely than men to develop the condition,[76] and occupations involving prolonged hand use.[77] Another compressive neuropathy, Guyon's canal syndrome, results from ulnar nerve compression in the ulnar tunnel at the wrist, causing pain, paresthesia, and motor deficits in the ring and little fingers, as well as intrinsic hand muscle weakness.[78] Common etiologies include space-occupying lesions like ganglia or repetitive pressure, with symptoms varying by the zone of compression within the canal.[79] Degenerative disorders frequently affect the wrist's joints, leading to cartilage breakdown and inflammation. Osteoarthritis of the wrist primarily involves the radiocarpal joint, manifesting as pain, stiffness, and reduced range of motion, and can develop as a primary condition or secondary to prior joint stress.[80] In primary forms, it results from age-related wear, while post-traumatic variants accelerate degeneration through altered joint mechanics.[81] Rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune inflammatory disease, commonly involves the wrist, affecting approximately 75% of patients,[82] causing synovitis, joint erosion, and deformities such as radial deviation or ulnar translocation of the carpus.[83] Early wrist involvement occurs in about 50% of cases within two years of diagnosis, contributing to functional impairment through capsular stretching and ligamentous laxity.[84] Other non-degenerative pathologies include ganglion cysts, which are benign, fluid-filled sacs arising from mucoid degeneration of the joint capsule or tendon sheath, most commonly on the dorsal wrist.[85] These cysts, comprising 60-70% of hand tumors, often present as painless masses but can cause discomfort or nerve compression if large.[86] De Quervain's tenosynovitis involves inflammation and thickening of the tendon sheaths enclosing the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons in the first dorsal compartment, resulting in radial wrist pain exacerbated by thumb motion.[87] This condition stems from repetitive thumb and wrist use, leading to stenosing tenosynovitis and potential myxoid degeneration.[88] Kienböck's disease represents avascular necrosis of the lunate bone, progressing through stages of sclerosis, fragmentation, and collapse, which causes dorsal wrist pain and limited extension.[89] The etiology involves disrupted blood supply to the lunate, often linked to negative ulnar variance, with the disease typically affecting young adults aged 20-40.[90] Congenital disorders like Madelung's deformity arise from abnormal development of the distal radial growth plate, leading to volar and ulnar tilting of the distal radius, prominence of the distal ulna, and carpal malalignment.[91] This condition, often associated with Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis due to SHOX gene mutations, results in progressive wrist deformity and pain during adolescence, with females more commonly affected.[92] The partial premature closure of the volar-ulnar physis disrupts normal radial growth, causing a characteristic "V-shaped" carpal arch and potential limitation in forearm rotation.[93]Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis of wrist conditions typically begins with a thorough physical examination to assess tenderness, swelling, range of motion, grip strength, and specific provocative tests tailored to suspected issues.[94] For instance, Phalen's test, which involves flexing the wrist for 60 seconds to reproduce symptoms of median nerve compression, is commonly used to evaluate carpal tunnel syndrome.[95] Additional nerve conduction studies and electromyography (EMG) may measure electrical activity in muscles and nerve impulses to confirm nerve involvement.[94] Imaging plays a central role in visualizing structural abnormalities. X-rays are the initial modality to detect fractures, dislocations, or signs of osteoarthritis, providing quick assessment of bone alignment.[94] For more detailed evaluation of soft tissues, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses radio waves and magnets to image ligaments, tendons, and cartilage, while ultrasound offers a noninvasive view of tendons, cysts, and dynamic structures.[94] Computed tomography (CT) scans provide high-resolution bone detail, particularly useful for complex fractures missed on X-rays.[94] In cases of persistent unexplained pain, wrist arthroscopy serves as a diagnostic tool, inserting a fiber-optic camera through small incisions to directly inspect the joint interior and potentially perform therapeutic interventions.[96] Treatment strategies for wrist conditions emphasize conservative measures initially, progressing to surgical options if symptoms persist or severity warrants. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen reduce pain and swelling, while splinting or casting immobilizes the wrist to promote healing in sprains or fractures.[94] Physical therapy incorporates ergonomic adjustments and modalities like ice application or corticosteroid injections for targeted inflammation relief.[94] For overuse injuries, rest and activity modification are foundational, often combined with ultrasound-guided therapies.[97] Surgical interventions address structural damage when conservative approaches fail. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) uses plates and screws to stabilize distal radius fractures, ensuring proper alignment for healing.[98] Carpal tunnel release involves cutting the transverse carpal ligament to decompress the median nerve, available via open or endoscopic techniques to minimize recovery time.[95] Ligament reconstruction or arthroscopic debridement repairs tears in the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) or removes loose bodies.[96] Rehabilitation focuses on restoring function post-injury or surgery through supervised exercises. Range-of-motion activities, such as wrist flexion and extension stretches held for five seconds, prevent stiffness, while progressive strengthening with therapy putty or resistance bands builds grip and forearm endurance.[99] These are typically initiated after immobilization, emphasizing gradual return to activities under professional guidance.[98] Recovery outcomes vary by condition severity and treatment modality, with most patients achieving significant improvement within weeks to months. For distal radius fractures, cast immobilization lasts about six weeks, followed by therapy, allowing light activities in 1-2 months and full recovery up to one year.[98] Mild sprains often resolve in 2-4 weeks with conservative care, though surgical cases like carpal tunnel release may yield relief within days but require 4-6 weeks for full hand use.[95] Persistent stiffness or ache can linger for months, underscoring the importance of adherence to rehabilitation protocols.[98]History

Etymology

The English word "wrist" derives from Old English wrist, referring to the joint connecting the hand to the forearm, which itself stems from Proto-Germanic *wristiz, a term denoting the back of the hand or instep.[100] This Proto-Germanic root traces back to the Proto-Indo-European *wris- or *wr̥stís, meaning "to turn" or "twist," an etymology that aptly reflects the wrist's rotational capabilities in human anatomy.[100] Cognates appear in related languages, such as Old Norse rist for instep and modern German Rist for wrist or ankle, illustrating the term's evolution within the Germanic family.[101] In medical and anatomical contexts, the term "carpus" has been influential, borrowed into Latin from Ancient Greek karpós (καρπός), originally meaning "wrist" and later extended metaphorically to "fruit" or "crop" due to its plucking action.[102] The Greek karpós for wrist likely shares a conceptual link with turning or twisting motions, paralleling the Indo-European roots of "wrist" through possible connections to verbs of rotation in Germanic languages.[102] This term entered English via Modern Latin carpus around the 1670s, becoming the standard for the wrist's bony structure in scientific nomenclature, as seen in "carpal bones."[102] Historically, the adoption of "carpus" in anatomical texts began prominently with Andreas Vesalius's De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543), where he employed it to describe the wrist joint and its ossa carpi, marking a shift toward precise Greco-Latin terminology in Renaissance anatomy.[103] Prior to this, English usage of "wrist" in medical writing was more vernacular, but Vesalius's work standardized "carpus" across Europe, influencing subsequent treatises on the upper limb.[104]Anatomical discoveries

The earliest known descriptions of wrist anatomy date to ancient Greece, where Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE) identified the wrist as comprising eight small bones, termed the carpal bones, and documented patterns of carpal dislocations resembling modern classifications, such as those involving the lunate or scaphoid.[105] In the 2nd century CE, Galen of Pergamon advanced understanding of wrist ligaments through dissections, primarily of animals, describing their role in stabilizing the joint and distinguishing between flexor and extensor tendons crossing the wrist, though his human applications were limited by reliance on non-human models.[106] During the Renaissance, Andreas Vesalius revolutionized wrist anatomy with his 1543 publication De Humani Corporis Fabrica, which included detailed woodcut illustrations of the eight carpal bones in multiple views, correcting over 200 errors in Galen's work, such as the precise arrangement of the proximal and distal rows and their articulations with the radius and ulna.[107] Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente, Vesalius's successor, contributed in the early 1600s through surgical texts like Operationes Chirurgicae (1619), where he detailed the synovial tendon sheaths enclosing flexor and extensor tendons at the wrist, emphasizing their role in reducing friction during motion.[108] In the 19th century, Abraham Colles provided a seminal description of distal radius fractures extending to the carpal joint in his 1814 paper "On the Fracture of the Carpal Extremity of the Radius," noting the characteristic dorsal displacement and its implications for wrist alignment, based on clinical observations without imaging.[109] Wilhelm Roux's developmental mechanics framework in the late 1800s influenced studies of carpal kinematics, proposing that joint form adapts to functional stresses, which informed early analyses of wrist motion patterns like radial-ulnar deviation.[110] The 20th century saw recognition of the scapholunate ligament's critical role in wrist stability, with Linscheid et al. (1972) classifying scapholunate dissociation as a primary cause of carpal instability, leading to dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) patterns observable on radiographs.[111] In the 2020s, advances in 3D computed tomography (CT) imaging have enhanced visualization of wrist biomechanics; for instance, a 2024 cadaveric study used dynamic 3D CT to quantify carpal bone translations post-scapholunate transection, revealing up to 2 mm proximal migration of the scaphoid under load.[112] Recent ossification research post-2020, such as a 2021 radiographic analysis, has refined timelines for carpal bone maturation, confirming capitate and hamate as the earliest to ossify (around 1–3 months postnatally) and linking accessory ossicles to 15–20% incidence in adults, aiding forensic and clinical assessments.[113]References

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1613214/

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/wrist

.jpeg/250px-Nadgarstek_(ubt).jpeg)

.jpeg)