Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anatomical terms of location

View on Wikipedia

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anatomical terminology |

|---|

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position provides a definition of what is at the front ("anterior"), behind ("posterior") and so on. As part of defining and describing terms, the body is described through the use of anatomical planes and axes.

The meaning of terms that are used can change depending on whether a vertebrate is a biped or a quadruped, due to the difference in the neuraxis, or if an invertebrate is a non-bilaterian. A non-bilaterian has no anterior or posterior surface for example but can still have a descriptor used such as proximal or distal in relation to a body part that is nearest to, or furthest from its middle.

International organisations have determined vocabularies that are often used as standards for subdisciplines of anatomy. For example, Terminologia Anatomica, Terminologia Neuroanatomica, and Terminologia Embryologica for humans and Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria for animals. These allow parties that use anatomical terms, such as anatomists, veterinarians, and medical doctors, to have a standard set of terms to communicate clearly the position of a structure.

Introduction

[edit]

Standard anatomical terms of location have been developed, usually based on Latin and Greek words, to enable all biological and medical scientists, veterinarians, medical doctors and anatomists to precisely delineate and communicate information about animal bodies and their organs, even though the meaning of some of the terms often is context-sensitive.[1][2] Much of this information has been standardised in internationally agreed vocabularies for humans (Terminologia Anatomica, Terminologia Neuroanatomica, and Terminologia Embryologica),[3][4] with Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria and Nomina Embryologica Veterinaria used for animal anatomy.[5]

Different terms are used for those vertebrates that are bipedal and those that are quadrupedal.[1] The reasoning is that the neuraxis, and therefore the standard anatomical position is different between the two groups.[2] Unique terms are also used to describe invertebrates, because of their wider variety of shapes and symmetries.[6]

Standard anatomical position

[edit]

Because animals can change orientation with respect to their environment, and because appendages like limbs and tentacles can change position with respect to the main body, terms to describe position need to refer to an animal when it is in its standard anatomical position, even when its appendages are in another position. This helps to avoid confusion in terminology when referring to the same animal in different postures.[7] In humans, this refers to the body in a standing position with arms at the side and palms facing forward.[8][7] In quadrupeds this is an animal standing upright with all four feet on the ground and the head facing forward.[9] For a fish this is belly down with neutral appendages.[10]

Planes

[edit]

Anatomical terms describe structures with relation to three main anatomical planes.[8] Anatomical planes are useful in a number of fields including medical imaging, embryology, and the study of movement.[11]

The three main plane orientations are:

- The sagittal planes, also called the parasagittal planes or paramedian planes, are planes that divide the body into left and right.[1][12] The central one of these is the median plane, also called the midsagittal plane, which passes through the head, spinal cord, navel and, in many animals, the tail.[13]

- The coronal plane or frontal plane divides the body into front and back parts.[8] In quadrupeds this plane is termed the dorsal plane and divides the body into dorsal (towards the backbone) and ventral (towards the belly) parts.[14][6]

- The transverse plane, also called the axial plane or horizontal plane, is perpendicular to the other two planes.[8]

Sagittal planes and transverse planes are used as anatomical lines to delineate bodily regions. There are several transverse planes with clinical relevance in the division of the torso into sections. They include the transpyloric plane, the subcostal plane, and the transumbilical plane.[15]

Axes

[edit]

The three axes of a vertebrate, are formed in embryonic development before and during the gastrulation stage.[16] Distinct ends of the embryo are chosen, and the axis is named according to those directions. The three main axes of a bilaterally symmetrical animal that intersect at right angles, are the left-right, the craniocaudal, and the anteroposterior axes.[16][6]

- The left-right axis, also known as the horizontal or frontal axis[16]

- The craniocaudal axis, also known as the rostrocaudal, longitudinal or cephalocaudal[16]

- The anteroposterior axis, also known as the dorsoventral, or sagittal axis[17][18]

An organism that is round, or asymmetrical may have different axes.[6]

Main terms

[edit]

Superior and inferior

[edit]In the standard human anatomical position, superior (from Latin super 'above') or cranial, describes something that is nearer to the head, and inferior (from Latin inferus 'below') or caudal describes what is below, and nearer to the feet.[7] Examples are the superior mediastinum, and inferior mediastinum. Neuroanatomy examples are the superior colliculus, and the inferior colliculus.[12] In veterinary anatomy, the terms superior and inferior are not used except to describe the eye, eyelids, lips and inner ear, using instead dorsal and ventral.[1]

Anterior and posterior

[edit]Anterior (from Latin ante 'before') describes what is in front, and posterior (from Latin post 'after') describes what is to the back of something.[19] For example, for many fish the gill openings are posterior to the eyes and anterior to the tail. In veterinary anatomy, these terms are reserved for some structures of the head, instead using cranial and caudal throughout the rest of the body.[14]

Dorsal and ventral

[edit]These two terms, used in veterinary anatomy, are also used in human anatomy mostly in neuroanatomy, and embryology, to describe something at the back (dorsal, posterior) or front (ventral, anterior) of an organ, or organism.[19]

The dorsal (from Latin dorsum 'back') surface, (also dorsum) of an organism or organ, refers to the back, or upper side, such as in the human, the dorsum of the tongue, the dorsum of the hand, and the dorsum of the foot. If talking about the skull, the dorsal side is the top.[18][12]

The ventral (from Latin venter 'belly') surface refers to the front, or lower side, of an organism, or organ such as the undersurface of the tongue.[18]

In a fish, the dorsal fin is on the upper surface and its ventral fins (pelvic fins) are on the belly or undersurface.[20]

The terms are used in other contexts, for example in dorsal and ventral gun turrets on a bomber aircraft.

Medial and lateral

[edit]These terms describe how close something is to the median plane.[2][19] Lateral (from Latin lateralis 'to the side') describes something to the sides of an animal, as in "left lateral" and "right lateral". Medial (from Latin medius 'middle') describes structures close to the median plane, or closer to the median plane than another structure.[19] For example, in a human, the arms are lateral to the torso. The genitals are medial to the legs. Temporal has a similar meaning to lateral but is restricted to the head.

The terms "left" and "right", or sinistral and dextral, refer to the halves of a bilaterally symmetrical body divided by the median plane.

Terms derived from lateral include:

- Contralateral (from Latin contra 'against'): on the side opposite to another structure. For example, the right arm and leg are controlled by the left, contralateral, side of the brain.

- Ipsilateral (from Latin ipse 'same'): on the same side as another structure. For example, the left arm is ipsilateral to the left leg.[12]

- Bilateral (from Latin bis 'twice'): on both sides of the body.[12] For example, bilateral orchiectomy means removal of testes on both sides of the body.

- Unilateral (from Latin unus 'one') one-sided or single-sided: on one side of the body.[12] For example, unilateral deafness is hearing impairment in one ear.[21]

Varus (from Latin 'bow-legged') and valgus (from Latin 'knock-kneed' ) are terms used to describe angulation or bowing of a bone or joint within the coronal plane, where the distal portion deviates towards (varus) or away from (valgus) the midline.[22]

Proximal and distal

[edit]

The terms proximal (from Latin proximus 'nearest') and distal (from Latin distare 'to stand away from') are used to describe parts of a feature that are close to or distant from the main mass of the body, respectively.[23] Thus the upper arm in humans is proximal and the hand is distal. The main mass is taken as the center, the chest, or the heart.[24]

"Proximal and distal" are frequently used when describing appendages, such as fins, tentacles, and limbs. Although the direction indicated by "proximal" and "distal" is always respectively towards or away from the point of attachment, a given structure can be either proximal or distal in relation to another point of reference. Thus the elbow is distal to a wound on the upper arm, but proximal to a wound on the lower arm.[24]

This terminology is also employed in molecular biology and therefore by extension is also used in chemistry, specifically referring to the atomic loci of molecules from the overall moiety of a given compound.[25]

Rostral, cranial, and caudal

[edit]

Specific terms exist to describe how close or far something is to the head or tail of an animal. To describe how close to the head of an animal something is, three distinct terms are used:

- Rostral (from Latin rostrum 'beak, nose') describes something situated toward the oral or nasal region, or in the case of the brain, toward the tip of the frontal lobe.[12][19]

- Cranial (from Greek κρανίον 'skull') or cephalic (from Greek κεφαλή 'head') describes how close something is to the head of an organism.[12]

- Caudal (from Latin cauda 'tail') describes how close something is to the trailing end of an organism.[19]

These terms are generally preferred in veterinary medicine and not used as often in human medicine.[26][27] For example, in horses, the eyes are caudal to the nose and rostral to the back of the head.[1]

In humans, "cranial" and "cephalic" are used to refer to the skull, with "cranial" being used more commonly. The term "rostral" is rarely used in human gross anatomy and refers more to the front of the face than the superior aspect of the organism. But it is used in embryology, and neuroanatomy. Similarly, the term "caudal" is used more in embryology and neuroanatomy, and only occasionally in human gross anatomy.[2] The "rostrocaudal axis" refers to the curved line of the neuraxis from the forehead (rostral) towards the tail end (caudal).

Central and peripheral

[edit]Central and peripheral refer to the distance towards and away from the centre of something. That might be an organ, a region in the body, or an anatomical structure. For example, the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous systems.

Central (from Latin centralis) describes something at, or close to the centre.[28] For example, the great vessels run centrally through the body; many smaller vessels branch from these.

Peripheral (from Latin peripheria, originally from Ancient Greek) describes something that is situated nearer to the body's surface, such as a peripheral nerve.[29]

Superficial and deep

[edit]These terms refer to the distance of a structure from the surface.[2][30]

Deep (from Old English) describes something further away from the surface of the organism.[30] For example, the external oblique muscle of the abdomen is deep to the skin. "Deep" is one of the few anatomical terms of location derived from Old English rather than Latin – the anglicised Latin term would have been "profound" (from Latin profundus 'due to depth').[1]

Superficial (from Latin superficies 'surface') describes something near the outer surface of the organism.[1] For example, in skin, the epidermis is superficial to the subcutis.[30]

Combined terms

[edit]

Many anatomical terms can be combined, either to indicate a position in two axes simultaneously or to indicate the direction of a movement relative to the body. For example, anterolateral indicates a position that is both anterior and lateral to the body axis (such as the bulk of the pectoralis major muscle), or to a named organ such as the anterolateral tibial tubercle.[31] The term can also describe the direction and location of something that enters or courses through the body such as the anterolateral system in the spinal cord, and the anterolateral central arteries.[32] Another term anteromedial is used for example in the anteromedial central arteries.[33]

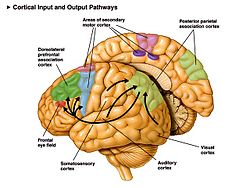

In the more internal brain and spinal cord of the central nervous system the terms dorsal and ventral and their combinations are often used in place of anterior and posterior. In these organs numerous references need to be used, and in the brain for example the prefrontal cortex has the divisions of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. And the dorsomedial region has subcompartments that make use of other terms such as the anterior cingulate cortex, and infralimbic cortex. Structures such as the anterior cingulate cortex may be divided anatomically based on cognitive (dorsal), and emotional (ventral) components.[34]

Proximodistal is the axis of an appendage such as an arm or a leg, taken from its tip at the distal part to where it joins the body at the proximal part.[17]

In radiology, various X-ray views uses terminology based on where the X-ray beam enters and leaves the body, including the front to back view (anteroposterior), the back to front view (posteroanterior), and the side view (lateral).[35] Combined terms were once generally hyphenated, but typically the hyphen is omitted.[36]

Modifiers

[edit]

Several terms are commonly seen and used as prefixes:[37]

- Sub- (from Latin sub 'preposition beneath, close to, nearly etc') is used to indicate something that is beneath, or something that is subordinate to or lesser than.[37] For example, subcutaneous means beneath the skin.

- Hypo- (from Ancient Greek ὑπό 'under') is used to indicate something that is beneath.[37] For example, the hypoglossal nerve supplies the muscles beneath the tongue.

- Infra- (from Latin infra 'under') is used to indicate something that is within or below. For example, the infraorbital nerve runs within the orbit.

- Inter- (from Latin inter 'between') is used to indicate something that is between.[37] For example, the intercostal muscles run between the ribs.

- Super- or Supra- (from Latin super, supra 'above, on top of') is used to indicate something that is above something else.[37] For example, the supraorbital ridges are above the eyes.

- Ab- (from Latin ab 'away'), and ad- (from Latin ad 'towards') are used to indicate that something is towards (ad-) or away from (ab-) something else.[37] For example abduction and adduction refer to muscular movement away from, and towards the midline of the body, respectively.

Other terms are used as suffixes, added to the end of words:

- -al (from Latin al 'pertaining to, of the') For example femoral neck.

- -ad (from Latin ad 'towards'), equivalent to '-ally', is a suffix createing the adverb form to indicate that something moves towards (-ad) something else.[38] For example, "distad" means "in the distal direction,"[39] as in "arterial blood flows distad/distally." Further examples may include cephalad (towards the cephalic end), orad, craniad, and proximad. The terms "proximally" and "distally" are in more common use in human and veterinary anatomic textbooks, while "proximad" and "distad," are used commonly in insect anatomy.[2][1][38]

Other terms and special cases

[edit]Anatomical landmarks

[edit]The location of anatomical structures can also be described in relation to different anatomical landmarks used in anatomy, surface anatomy, surgery, and radiology.[40]

Structures may be described as being at the level of a specific vertebra, depending on the section of the vertebral column the structure is at.[40] The position is often abbreviated. For example, structures at the level of the fourth cervical vertebra may be abbreviated as "C4", at the level of the fourth thoracic vertebra "T4", and at the level of the third lumbar vertebra "L3". Because the sacrum and coccyx are fused, they are not often used to provide the location.

References may also take origin from surface anatomy, made to landmarks that are on the skin or visible underneath.[40] For example, structures may be described relative to the anterior superior iliac spine, the medial malleolus or the medial epicondyle.

Anatomical lines are theoretical lines, using either horizontal transverse planes, or vertical sagittal planes, used to describe anatomical location. For examples, the mid-clavicular line is used as part of the cardiac examination to feel the apex beat of the heart, and the axillary lines are reference lines for the underarm region. Other types of lines in anatomy include the curved nuchal lines on the occipital bone, and the gluteal lines on the ilium.

Mouth and teeth

[edit]Special terms are used to describe the mouth and teeth.[2] Fields such as osteology, paleontology and dentistry apply special terms of location to describe the mouth and teeth. This is because although teeth may be aligned with their main axes within the jaw, some different relationships require special terminology as well; for example, teeth also can be rotated, and in such contexts terms like "anterior" or "lateral" become ambiguous.[41][42] For example, the terms "distal" and "proximal" (or "mesial") are used for surfaces of individual teeth relative to the midpoint of the dental arch, and "medial" and "lateral" are used in the standard sense relative to the median plane.[43] Terms used to describe structures include "buccal" (from Latin bucca 'cheek') and "palatal" (from Latin palatum 'palate') referring to structures close to the cheek and hard palate respectively.[43]

Hands and feet

[edit]

Several anatomical terms are particular to the hands and feet.[2] Additional terms may be used to avoid confusion when describing the surfaces of the hand and what is the "anterior" or "posterior" surface. The term "anterior", while anatomically correct, can be confusing when describing the palm of the hand; Similarly is "posterior", used to describe the back of the hand and arm. This confusion can arise because the forearm can pronate and supinate and flip the location of the hand. For improved clarity, the directional term palmar (from Latin palma 'palm of the hand') is commonly used to describe the front of the hand, and dorsal is the back of the hand. The palmar fascia is palmar to the tendons of muscles which flex the fingers, and the dorsal venous arch is so named because it is on the dorsal side of the foot.

In humans, volar can also be used synonymously with palmar to refer to the palm of the hand, and can also be used to refer to the sole of the foot.[44] But palmar is used exclusively for the palm of the hand, and plantar is used exclusively for the sole of the foot.[44][45]

Similarly, in the limbs for clarity, the sides are named after the bones. In the forearm, structures closer to the radius are radial, structures closer to the ulna are ulnar, and structures relating to both bones are referred to as radioulnar, such as the distal radioulnar joint.[46] Similarly, in the lower leg, structures near the tibia (shinbone) are tibial and structures near the fibula are fibular (or peroneal).

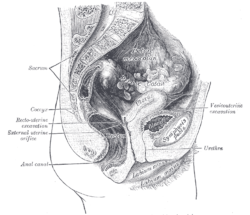

Rotational direction

[edit]Anteversion and retroversion are complementary terms describing an anatomical structure that is rotated forwards (towards the front of the body) or backwards (towards the back of the body), relative to some other position. They are particularly used to describe the curvature of the uterus.[47][48]

- Anteversion (from Latin anteversus) describes an anatomical structure being tilted further forward than normal, whether pathologically or incidentally.[47] For example, a person's uterus typically is anteverted, tilted slightly forward. A misaligned pelvis may be anteverted, that is to say tilted forward to some relevant degree.[49]

- Retroversion (from Latin retroversus) describes an anatomical structure tilted back away from something.[48] An example is a retroverted uterus.[48]

Other directional terms

[edit]Several other terms are also used to describe location. These terms are not used to form the fixed axes. Terms include:

- Axial (from Latin axis 'axle'): around the central axis of the organism or the extremity.[50] Two related terms, "abaxial" and "adaxial", refer to locations away from and toward the central axis of an organism, respectively[51]

- Luminal (from Latin lumen 'light, opening'): on the—hollow—inside of an organ's lumen (body cavity or tubular structure);[52][53] adluminal is towards, abluminal is away from the lumen.[54] Opposite to outermost (the adventitia, serosa, or the cavity's wall).[55]

- Terminal (from Latin terminus 'boundary or end') at the extremity of a usually projecting structure; forming the end of a structure such as an axon terminal.[56]

- Visceral (from Latin viscera 'internal organs'): associated with the innermost layer of an organ within the body. For example, the visceral pleura covering the lungs, contrasted with the parietal pleura lining the thoracic cavity.[57]

- Parietal (from Latin paries 'wall'): pertaining to the wall of a body cavity as the parietal pleura lining the thoracic cavity, contrasted with visceral pleura.[57]

- Aboral (away from oral) is used to denote a location in an organism that is further from the mouth.

Other animals

[edit]Different terms are used because of different body plans in animals, whether animals stand on two or four legs, and whether an animal is symmetrical or asymmetrical. For example, as humans are bilaterally symmetrical, anatomical descriptions usually use the same terms as those for other vertebrates.[13] However, the standard human anatomical position means that their anterior/posterior and ventral/dorsal directions are the same, so the inferior/superior directions are used due to longstanding tradition instead of cranial/caudal, which apply regardless of position, as in other species.[58] The term "rostral" used to refer to the beak or nose in some animals is used less frequently in humans, with the exception of parts of the brain;[19] while humans do not have a visible tail (the coccygeal vertebrae are present and commonly called the "tailbone") the term "caudal" that refers to the tail-end is also sometimes used in humans and animals without tails to refer to the hind part of the body.[19] Flounder and other flatfish which lie on the seabed on their left or right side are asymmetric, with both eyes on the 'up' side, making anatomical nomenclature a challenge.[59]

Invertebrates have a large variety of body shapes that can present a problem when trying to apply standard directional terms. Depending on the organism, some terms are taken by analogy from vertebrate anatomy, and appropriate novel terms are applied as needed. Some such borrowed terms are widely applicable in most invertebrates; for example proximal, meaning "near" refers to the part of an appendage nearest to where it joins the body, and distal, meaning "standing away from" is used for the part furthest from the point of attachment. In all cases, the usage of terms is dependent on the body plan of the organism.

-

Anatomical terms of location in a dog

-

Anatomical terms of location in a kangaroo

-

Anatomical terms of location in most fish

-

Anatomical terms of location in a horse

-

Flatfish are asymmetric, with both eyes lying on the same side of the head.

Non-bilaterian organisms

[edit]

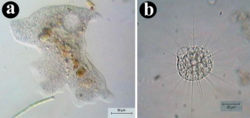

In non-bilaterian organisms with a changeable shape, such as amoeboid organisms, most directional terms are meaningless, since the shape of the organism is not constant and no distinct axes are fixed. Similarly, in radially symmetrical organisms, there is nothing to distinguish one line through the centre of the organism from any other. An indefinite number of triads of mutually perpendicular axes could be defined, but any such choice of axes would be useless, as nothing would distinguish a chosen triad from any others. In such organisms, only terms such as superficial and deep, or sometimes proximal and distal, are usefully descriptive.

Elongated organisms

[edit]

In organisms that maintain a constant shape and have one dimension longer than the other, at least two directional terms can be used. The long or longitudinal axis is defined by points at the opposite ends of the organism. Similarly, a perpendicular transverse axis can be defined by points on opposite sides of the organism. There is typically no basis for the definition of a third axis. Usually such organisms are planktonic (free-swimming) protists, and are nearly always viewed on microscope slides, where they appear essentially two-dimensional. In some cases a third axis can be defined, particularly where a non-terminal cytostome or other unique structure is present.[60]

Some elongated protists have distinctive ends of the body. In such organisms, the end with a mouth (or equivalent structure, such as the cytostome in Paramecium or Stentor), or the end that usually points in the direction of the organism's locomotion (such as the end with the flagellum in Euglena), is normally designated as the anterior end. The opposite end then becomes the posterior end.[60] Properly, this terminology would apply only to an organism that is always planktonic (not normally attached to a surface), although the term can also be applied to one that is sessile (normally attached to a surface).[61]

Organisms that are attached to a substrate, such as sponges and animal-like protists also have distinctive ends. The part of the organism attached to the substrate is usually referred to as the basal end (from Latin basis 'support/foundation'), whereas the end furthest from the attachment is referred to as the apical end (from Latin apex 'peak/tip').

Radially symmetrical organisms

[edit]Radially symmetrical organisms include those in the group Radiata – primarily Cnidarians (jellyfish, sea anemones and corals, and the comb jellies).[62] Adult echinoderms, such as starfish, sea urchins, sea cucumbers and others are also included, since they have a pentamerous symmetry having five discrete symmetric parts arranged around a central axis.[63] Echinoderm larvae are not included, since they are bilaterally symmetrical.[63]

Cnidarians have an incomplete digestive system, meaning that one end of the organism has a mouth, the oral end (from Latin ōrālis 'of the mouth'), and the opposite aboral end (from Latin ab- 'away from') has no opening from the gut (coelenteron).[62] They are radially symmetric around the oral-aboral axis.[62] Having only the single distinctive axis, "lateral", "dorsal", and "ventral" have no meaning, and all can be replaced by the generic term peripheral (from Ancient Greek περιφέρεια 'circumference'). Medial can be used, but in the case of radiates indicates the central point, rather than a central axis as in vertebrates. Thus, there are multiple possible radial axes and medio-peripheral (half-) axes.[64]

Comb jellies have a biradial symmetry about only two planes, a tentacular plane, and a pharyngeal plane.[65]

-

Aurelia aurita, another species of jellyfish, showing multiple radial and medio-peripheral axes

-

The sea star Porania pulvillus, aboral and oral surfaces

Spiders

[edit]Special terms are used for spiders. Two such terms are useful in describing views of the legs and pedipalps of spiders, and other arachnids. Prolateral refers to the surface of a leg that is closest to the anterior end of an arachnid's body. Retrolateral refers to the surface of a leg that is closest to the posterior end of an arachnid's body.[66] Most spiders have eight eyes in four pairs. All the eyes are on the carapace of the prosoma, and their sizes, shapes and locations are characteristic of various spider families and other taxa.[67] Usually, the eyes are arranged in two roughly parallel, horizontal and symmetrical rows of eyes.[67] Eyes are labelled according to their position as anterior and posterior lateral eyes (ALE) and (PLE); and anterior and posterior median eyes (AME) and (PME).[67]

-

Aspects of spider anatomy. This aspect shows the mainly prolateral surface of the anterior femora, plus the typical horizontal eye pattern of the Sparassidae.

-

Typical arrangement of eyes in the Lycosidae, with PME being the largest

-

In the Salticidae the AME are the largest.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Dyce, Keith M.; Sack, Wolfgang O.; Wensing, Cornelis Johannes Gerardus (2010). Textbook of veterinary anatomy (4th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-4160-6607-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Standring, Susan (2016). Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (41. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier. pp. xvi–xvii. ISBN 978-0-7020-5230-9.

- ^ "TE entry page" (PDF). IFAA. Retrieved 27 February 2025.

- ^ "International Federation of Associations of Anatomists". Dalhousie University. Retrieved 22 March 2025.

- ^ "Documents and publications". World Association of Veterinary Anatomists. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d Kardong, Kenneth V. (2019). Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution (Eighth, international student ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-260-09204-2.

- ^ a b c "1.4A: Anatomical Position". Medicine LibreTexts. 18 July 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Introduction". Collection at Bartleby.com. 20 October 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ Kumar, M.S.A. (2015). Clinically oriented anatomy of the dog & cat. Linus Learning. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-60797-552-6. Retrieved 2025-05-08.

- ^ Earls, James (2023). Functional Anatomy of Movement: An Illustrated Guide to Joint Movement, Soft Tissue Control, and Myofascial Anatomy-- For Yoga Teachers, Pilates Instructors & Movement & Manual Therapists. North Atlantic Books. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-62317-842-0. Retrieved 2025-05-08.

- ^ "1.4D: Body Planes and Sections". Medicine LibreTexts. 18 July 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F.; Agur, Anne M. R. (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia Baltimore New York London Buenos Aires Hong Kong Sydney Tokyo: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 5–8. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ a b Hyman, Libbie Henrietta (1979). Hyman's comparative vertebrate anatomy (3rd ed.). Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-226-87011-3.

- ^ a b Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria (6 ed.). World Association of Veterinary Anatomists. 2017. p. 9. Retrieved 2025-05-08.

- ^ "Regions and Planes of the Abdomen: Overview, Abdominal Skin, Superficial Fascia". 19 February 2025. Retrieved 10 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d Abas R, Masrudin SS, Harun AM, Omar NS (December 2022). "Gastrulation and Body Axes Formation: A Molecular Concept and Its Clinical Correlates". Malays J Med Sci. 29 (6): 6–14. doi:10.21315/mjms2022.29.6.2. PMC 9910376. PMID 36818899.

- ^ a b "Developmental Mechanism - Axes Formation - Embryology". embryology.med.unsw.edu.au. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ a b c "AmiGO 2: Term Details for "dorsal/ventral axis specification" (GO:0009950)". amigo.geneontology.org. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Purves, Dale; Augustine, George J.; Fitzpatrick, David; Katz, Lawrence C.; LaMantia, Anthony-Samuel; McNamara, James O.; Williams, S. Mark (2001). "Some Anatomical Terminology". Neuroscience. 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ "SCDNR - Fishing Information". www.dnr.sc.gov. Retrieved 27 February 2025.

- ^ Dodson, Kelley M; Georgolios, Alexandros; Barr, Noelle (2012). "Etiology of unilateral hearing loss in a national hereditary deafness repository". American Journal of Otolaryngology. 33 (5): 590–594. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2012.03.005. PMID 22534022.

- ^ Hacking, Craig (18 September 2014). "Valgus vs varus". Radiopedia. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ "Anatomical Terminology | SEER Training". training.seer.cancer.gov. Retrieved 10 March 2025.

- ^ a b "What do distal and proximal mean?". The Survival Doctor. 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2016-01-07.

- ^ Singh, S (8 March 2000). "Chemistry, design, and structure-activity relationship of cocaine antagonists". Chemical Reviews. 100 (3): 925–1024. doi:10.1021/cr9700538. PMID 11749256.

- ^ Hickman, C. P. Jr., Roberts, L. S. and Larson, A. Animal Diversity. McGraw-Hill 2003 ISBN 0-07-234903-4

- ^ Miller, S. A. General Zoology Laboratory Manual McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-252837-0 and ISBN 0-07-243559-3

- ^ "Definition of Central". www.merriam-webster.com. 23 March 2025. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "Peripheral". Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ a b c "1.4B: Directional Terms". Medicine LibreTexts. 18 July 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F.; Agur, Anne M. R. (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia Baltimore New York London Buenos Aires Hong Kong Sydney Tokyo: Wolters Kluwer. p. 679. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ "Anatonomina". terminologia-anatomica.org. Retrieved 2025-02-28.

- ^ "Anatonomina". terminologia-anatomica.org. Retrieved 2025-02-28.

- ^ Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI (June 2000). "Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 4 (6): 215–222. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01483-2. PMID 10827444. S2CID 16451230.

- ^ Hofer, Matthias (2006). The Chest X-ray: A Systematic Teaching Atlas. Thieme. p. 24. ISBN 978-3-13-144211-6.

- ^ "dorsolateral". Merriam-Webster. 29 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "medical terms". www.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 March 2025.

- ^ a b Gordh, Gordon; Headrick, David H (2011). A Dictionary of Entomology (2nd ed.). CABI. ISBN 978-1-84593-542-9.

- ^ "Medical Definition of Distad". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ a b c Butler, Paul; Mitchell, Adam W. M.; Ellis, Harold (1999-10-14). Applied Radiological Anatomy. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-48110-6.

- ^ Pieter A. Folkens (2000). Human Osteology. Gulf Professional Publishing. pp. 558–. ISBN 978-0-12-746612-5.

- ^ Smith, J. B.; Dodson, P. (2003). "A proposal for a standard terminology of anatomical notation and orientation in fossil vertebrate dentitions". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[1:APFAST]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 8134718.

- ^ a b Rajkumar, K.; Ramya, R. (2017). Textbook of Oral Anatomy, Physiology, Histology and Tooth Morphology. Wolters kluwer india Pvt Ltd. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-93-86691-16-3.

- ^ a b "Volar". Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ "Definition of Plantar". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Dyan V. Flores; Darwin Fernández Umpire; Kawan S. Rakhra; Zaid Jibri; Gonzalo A. Serrano Belmar (18 Nov 2022). "Distal Radioulnar Joint: Normal Anatomy, Imaging of Common Disorders, and Injury Classification". Radiographics. 43 (1) e220109. doi:10.1148/rg.220109. PMID 36399415. S2CID 253627145.

- ^ a b "Anteversion definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ a b c "Retroversion definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ Zhou, S; Zhao, Y; Sun, Z; Han, G; Xu, F; Qiu, W; Liu, T; Li, W (September 2024). "Impact of pelvic anteversion on spinopelvic alignment in an asymptomatic population: a dynamic perspective of standing and sitting". The Spine Journal. 24 (9): 1732–1739. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2024.04.001. PMID 38614156.

- ^ "Definition of Axial". www.merriam-webster.com. 15 March 2025. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ "Definition of Abaxial". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ William C. Shiel. "Medical Definition of Lumen". MedicieNet. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms "lumen"". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ ""abluminal"". Merriam-Webster.com Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ David King (2009). "Study Guide - Histology of the Gastrointestinal System". Southern Illinois University. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Definition of Terminal". www.merriam-webster.com. 15 March 2025.

- ^ a b "Pleura". 2 August 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2025.

- ^ Tucker, T. G. (1931). A Concise Etymological Dictionary of Latin. Halle (Saale): Max Niemeyer Verlag.

- ^ Schreiber, Alexander M. (15 February 2006). "Asymmetric craniofacial remodeling and lateralized behavior in larval flatfish". Journal of Experimental Biology. 209 (4): 610–621. doi:10.1242/jeb.02056.

- ^ a b Ruppert, EE; Fox, RS; Barnes, RD (2004). Invertebrate zoology: a functional evolutionary approach (7th ed.). Thomson, Belmont: Thomson-Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-03-025982-7.

- ^ Valentine, James W. (2004). On the Origin of Phyla. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-84548-7.

- ^ a b c Ruppert, EE; Fox, RS; Barnes, RD (2004). Invertebrate zoology: a functional evolutionary approach (7th ed.). Thomson, Belmont: Thomson-Brooks/Cole. p. 112. ISBN 0-03-025982-7.

- ^ a b Ruppert, EE; Fox, RS; Barnes, RD (2004). Invertebrate zoology: a functional evolutionary approach (7th ed.). Thomson, Belmont: Thomson-Brooks/Cole. pp. 873–875. ISBN 0-03-025982-7.

- ^ Oliveira, Otto Müller Patrão de. "Chave de identificação dos Ctenophora da costa brasileira". Biota Neotropica. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Ruppert, EE; Fox, RS; Barnes, RD (2004). Invertebrate zoology: a functional evolutionary approach (7th ed.). Thomson, Belmont: Thomson-Brooks/Cole. p. 184. ISBN 0-03-025982-7.

- ^ Kaston, B.J. (1972). How to Know the Spiders (3rd ed.). Dubuque, IA: W.C. Brown Co. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-697-04899-8. OCLC 668250654.

- ^ a b c Foelix, Rainer (2011). Biology of Spiders. Oxford University Press, US. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-19-973482-5.