Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to List of cave monasteries.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of cave monasteries

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

A cave monastery is a monastery built in caves, with possible outside facilities. The 3rd-century monk St. Anthony the Great, known as the founder of Christian monasticism, lived in a cave.

- Albania

- Qafthanë Cave Church, cave church near Urakë

- St. Mary's Church, cave church in Maligrad, an island in the Prespa lake

- Armenia

- Geghard cave monastery/fortress

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bulgaria

- Aladzha Monastery

- Albotin Monastery

- Basarbovo Monastery

- Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo

- Cave monasteries of Krepcha

- Monasteries of Provadia

- Cave monasteries on the Plateau of Shumen

- Cave monasteries of Tervel

- Egypt

- St. Simon the Tanner Monastery

- Ethiopia

- France

- Georgia

- David Gareja monastery complex

- Vanis Kvabebi cave monastery/fortress, Javakheti Plateau

- Vardzia cave city and monastery

- Greece

- various cave hermitages at Meteora

- various cave hermitages at Mount Athos

- caves at Karoulia

- Monastery of Saint Mark, Petroussa

- Hungary

- Gellért Hill Cave chapels and monastery, Budapest

- Iraq

- Rabban Hormizd Monastery, Alqosh

- Mar Qayuma Monastery, Dooreh

- Israel

- Qumran Caves, once inhabited by the Essenes

- Montenegro

- North Macedonia

- Romania

- Russia

- Serbia

- Blagoveštenje

- Crna Reka

- Gornjak

- Kađenica

- Churches of Kovilje Monastery

- Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, also known as the Cave Church, 14th-century church in Lukovo

- Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, in Rsovci, where was painted a unique fresco of bald Jesus

- Hermitage of St. Peter Koriški

- Savina

- Thailand

- Wat Tham Khan, Sakon Nakhon province

- Tiger Cave Temple (Wat Tam Sua), Krabi

- Turkey

- Cappadocia cave monasteries

- Cave monastery of İnceğiz

- Church of Saint Peter

- Ukraine

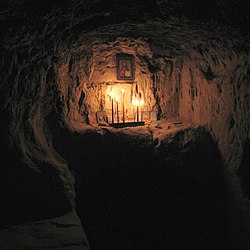

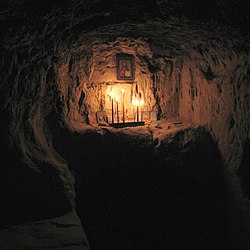

A cell in the caves of the Kytaiv Monastery - Bakhchysarai Cave Monastery in Crimea

- Chelter-Koba in Crimea

- Chylter-Marmara in Crimea

- Inkerman Cave Monastery in Crimea

- Assumption Cave Monastery in Zymne, Volyn Oblast

- Bakota Cave Monastery in Bakota, Khmelnytskyi Oblast

- Kachi-Kalon in Crimea

- Kyiv Pechersk Lavra (Near and Far Caves) in Kyiv

- Kytaiv Monastery in Kyiv

- Shuldan in Crimea

- Sviatohirsk Lavra in Sviatohirsk, Donetsk Oblast

- Yeletskyi Monastery (Saint Anthony's Caves) in Chernihiv

In Bulgaria

[edit]Northeast Bulgaria

[edit]- Rock monasteries near Ruse

- Basarbovo Monastery

- Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo

- Great Nisovo Rock Monastery (Голям Нисовски скален манастир), near Nisovo village

- Tabachka Cave Church, near Tabachka village

- Rock monasteries near Cherven village

- Malkiya Rai Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Малкия Рай“)

- Koshuta Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Кошута“)

- Golemiya Rai Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Големия рай“)

- Moskov Dol Rock Church (Скална църква „Москов Дол“)

- Krepcha Rock Monastery (Крепченски скален манастир), near Krepcha village

- Rock monasteries near Tervel

- Rock monasteries near Balik and Onogur villages

- Asar Evleri Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Асар евлери“)

- Gyaur Evleri Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Гяур евлери“)

- Sandakli Maara Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Сандъкли маара“)

- Tarapanata Rock Monastery (Скална обител „Тарапаната“)

- Valchanova Staya Rock Hermitage (Скален скит „Вълчанова стая“), near Brestnitsa village

- Rock monasteries near Balik and Onogur villages

- Varbino Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Върбино“), near Varbino village

- Haidushki Kashti Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Хайдушки къщи“), near Kolobar village

Provadiya river valley

[edit]Rock monasteries situated in and around the Provadiya river valley:

- Rock monasteries on the Shumen Plateau

- Osmar monasteries, near Osmar village

- Trinity (Troitsa) monasteries, near Troitsa village

- Hankrumovski Monastery, near Han Krum (Hankrum) village

- Divdyadovski Monastery, near Divdiyadovo village

- a 14th-century rock-hewn church on the northwestern edge of Shumen city

- Rock monasteries near Nevsha

- Gyurebahcha Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Гюребахча“)

- Petricha Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Петрича“), near Razdelna, Varna Province

- Kisheshlika Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Кишешлика“), near Avren, Varna Province

- Rock monasteries around Provadia

- Shashkanite Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Шашкъните“)

- Chukara Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Чукара“)

- Holy Archangel Gabriel Rock Chapel (Скален параклис „Св. Архангел Гавраил“)

- Sara Kaya Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Саръ кая“)

- Kara Cave Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Кара пещера“), just north of Manastir village

- Rock monasteries near Petrov Dol village

- St. George Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Свети Георги“)

- Golyamata / Big Rock Monastery (Seven Chambers / Hodaviah) (Скален манастир „Голямата канара“)

- Gradishte Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Градище“)

- Tapanite Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Тъпаните“), near Blaskovo village

- Rojak rock monasteries: Dzheneviz Kanara Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Дженевиз канара“) or Golyamata Kanara Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Голямата канара“), near Rojak village

- Aladzha Monastery near Varna

Others

[edit]- St. Stefan Rock Monastery (Скален манастир „Св. Стефан“), Nikopol

- Rock hermitages near the Krushuna Falls south of Krushuna village

- St. Nicholas Rock Monastery (Gligora) (Скален манастир „Свети Никола“ (Глигора)), near Karlukovo village

- St. Ivan Pusti Monastery (Манастир „Свети Иван Пусти”), near Bistrets, Vratsa Province

- Albotin Monastery, northwestern Bulgaria

See also

[edit]Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cave monasteries.

References

[edit]- ^ Abbey of Saint-Roman Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- "Mysteries of caves in the Chernihiv area", and article in Dzerkalo Tyzhnia, (the Mirror Weekly), January, 2004, available online in Russian and in Ukrainian

List of cave monasteries

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

A cave monastery is a monastic establishment or religious complex constructed within natural caves or excavated from rock faces, serving as secluded retreats for ascetics, monks, and religious communities dedicated to prayer, contemplation, and spiritual discipline across various traditions, including Christianity and Buddhism. These sites often incorporate rock-cut churches, tombs, living quarters, and artistic elements, providing protection from external threats while fostering cultural and scholarly activities. Notable examples include the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra in Ukraine, the oldest monastic complex of Kievan Rus' founded around 1051 CE by monk Anthony, featuring an extensive underground cave network used for burials and worship that evolved into a major center of Eastern Orthodox Christianity and printing.[1] In Armenia, the Monastery of Geghard, established in the 4th century CE following the Christianization of the region, exemplifies medieval rock-cut architecture with carved churches, a scriptorium, and tombs, named after the relic of the Holy Lance preserved there for centuries.[2] Buddhist cave monasteries, such as China's Mogao Caves near Dunhuang, developed from the 4th to 14th centuries CE along the Silk Road as vibrant hubs of artistic exchange, containing over 490 decorated caves with murals and sculptures that connected South Asian and East Asian traditions.[3] In Turkey's Cappadocia region, Byzantine-era cave monasteries carved into soft volcanic tuff from the 4th to 11th centuries CE formed hidden networks of hundreds of churches and monastic dwellings, reflecting eremitic and communal monasticism amid iconoclastic periods and invasions.[4]

Cave monasteries emerged prominently in the early centuries of organized monasticism, tracing roots to eremitic practices in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, such as those inspired by St. Anthony the Great in Egypt's desert caves, which influenced the spread of Christian asceticism to regions like the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond.[5] In Eastern Christianity, they proliferated in areas vulnerable to persecution, such as the Balkans and Anatolia, where rock formations allowed for defensible, self-sustaining communities; for instance, Bulgaria's Aladzha Monastery, dating to the 12th-14th centuries, combined cave cells with above-ground structures for a mixed monastic life. In Asia, Buddhist examples like India's Ellora Caves, excavated between the 6th and 10th centuries CE, integrated Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain rock-cut monasteries, showcasing architectural innovation and interfaith coexistence.[6] These complexes often served multifaceted roles, functioning as educational centers, artistic workshops, and pilgrimage destinations, with many now recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites for their preserved frescoes, sculptures, and historical testimony to religious endurance.[2]

The following list enumerates notable cave monasteries worldwide, organized by region and tradition, highlighting their locations, founding periods, and key features to illustrate the global diversity and enduring legacy of this architectural and spiritual form.

The Cave of the Apocalypse on the island of Patmos holds profound religious significance as the traditional site where the Apostle John the Theologian experienced divine visions and dictated the Book of Revelation around 95 AD. This early Christian hermitage, located midway between the ports of Skála and the settlement of Chorá, features small chapels and oratories developed around the natural fissure where John is said to have rested his head. The site integrates seamlessly with the surrounding karst terrain, symbolizing the island's enduring role as a center of Orthodox pilgrimage.[42]

Adjacent to the cave, the Holy Monastery of St. John the Theologian was established in 1088 by the monk Christodoulos under the patronage of Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, incorporating the sacred cavern into its fortified layout. The 11th-century core structures, including the Katholikón church and refectory, evolved over centuries into a castle-like ensemble that protected both monks and refugees during Ottoman rule. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1999 for its architectural and spiritual authenticity, the monastery exemplifies Greek Orthodox continuity in cave-based devotion.[42] North Macedonia

No specific cave monasteries are prominently documented in North Macedonia beyond broader rock-cut church traditions in sites like Zrze and Lesnovo.[43] Romania

The Ostrov Monastery, situated in the Danube cliffs near Călărași, traces its origins to a 10th-century cave church dedicated to St. Andrew the Apostle, who according to tradition preached in the region and used the site as a hermitage. Carved into the sheer bluffs overlooking the Danube, the rock-hewn chapel features ancient frescoes and serves as a focal point for pilgrimage, embodying early Christian evangelization north of the river. The complex expanded in later centuries but retains its core cave structure as a testament to Dobrogea's monastic heritage.[44]

Further north, the Skete of the Cave near Slătiioara, established in the 19th century as a hermitage within the Neamț Mountains, utilizes natural caverns for ascetic cells and prayer spaces, continuing Romania's tradition of sylvan reclusion. Founded by monks seeking solitude, the skete's cave elements support hesychast practices, with paths leading to secluded grottos used for contemplation and small-scale liturgy.[45] Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Zavala Monastery near Mostar integrates cave features into its 13th-century cliffside complex, with the northern wall of the church embedded directly into a karst cave on Ostrog Hill's slope. First documented in 1514 via a founder's seal, the site functioned as a Serbian Orthodox stronghold, its natural cave providing defensive shelter and symbolic depth for monastic life amid regional conflicts. The monastery's architecture merges Byzantine influences with local geology, hosting relics and serving as a pilgrimage hub in Herzegovina's Popovo Field.[46] Albania

In central Albania near Urakë, the Qafthanë Cave Church represents a medieval rock-hewn chapel, carved into a hillside as a secluded worship space during the Byzantine era. Designated a Cultural Monument of Albania, the site features simple excavated interiors suited for early Christian rites, underscoring the persistence of cave veneration in the region's Orthodox communities despite historical upheavals.

Near Shijak, the St. Nicholas Cave Church dates to early Christian times, functioning as a hermitage chapel with rock-cut niches for icons and altars. This modest site, tied to 6th-century monastic migrations, exemplifies Albania's underdocumented cave traditions, offering a quiet testament to pre-Ottoman piety in coastal cliffs. Italy

The Grottaferrata Abbey near Rome, founded in 1004 by St. Nilus of Rossano, derives its name from an ancient "crypta ferrata"—a Roman-era funerary cave sealed with iron grates—incorporating minor cave cells into its Basilian layout. As Italy's sole surviving Italo-Greek monastery, the 11th-century complex preserves Byzantine liturgical practices, with the original cave elements symbolizing the abbey's eremitic roots amid the Alban Hills.[47]

Europe

Bulgaria

Bulgaria is renowned for its extensive network of cave monasteries, primarily rock-hewn complexes dating from the 10th to 14th centuries during the Second Bulgarian Empire, reflecting the influence of early Christian Orthodox hermetic traditions. These sites, often carved into limestone cliffs along river valleys, served as retreats for monks and include churches, cells, and chapels, with many now preserved as cultural heritage despite being largely abandoned. Over 40 such documented sites exist across the country, concentrated in the northeast and along river gorges, emphasizing Bulgaria's role in medieval monastic architecture.[7] In the northeast Bulgaria cluster, near the Danube and Rusenski Lom River, several prominent examples stand out. The Basarbovo Monastery, located near Ruse, was founded in the 12th century and remains the only active cave monastery in Bulgaria today, featuring cave cells, a rock-hewn church dedicated to St. Dimitar Basarbovski, and a healing spring associated with the saint's relics.[8] Nearby, the Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979, comprise a complex of over 40 medieval churches, chapels, and cells excavated into the cliffs, renowned for their well-preserved 13th- and 14th-century frescoes depicting biblical scenes and hesychast monastic life.[9] The Great Nisovo Rock Monastery, situated near Nisovo village along the Malki Lom River, is a medieval rock-cut ensemble with multiple cells and a church, accessible via a steep staircase and offering insights into the region's hermit communities.[10] The Provadiya River Valley cluster, in the eastern Black Sea region, hosts multi-level cave complexes tied to 10th-12th century monastic activity. Aladzha Monastery, near Varna and the Golden Sands resort, is a standout example with its three-story structure including a church, refectory, and hermit cells carved into the karst cliffs, inhabited by monks from the 13th to 14th centuries before abandonment in the 17th century.[11] The Osmar Monasteries, a series of 14th-century cave hermitages near Osmar village in Shumen Province, feature rock-hewn churches and cells along steep slopes, part of the broader Shumen Plateau network and symbolizing the spiritual ascent of medieval Bulgarian monasticism.[12] Further south, the Trinity (Troitsa) Monasteries near Troitsa village include rock-hewn churches from the medieval period, integrated into natural caves and linked to the Orthodox tradition of hesychasm.[13] Other notable sites are scattered across northwestern and central Bulgaria. The Albotin Monastery, in the Vidin region near the village of Gradets, dates to the 11th century and includes a cave necropolis, rock church, and cells, once a refuge for Bogomil heretics and now a site for unique Easter rituals honoring the dead.[14] St. Stefan Rock Monastery, near Nikopol in the Plavala locality, is a 14th-century complex carved into limestone, comprising a church with ancient inscriptions and surrounding cells, declared a historical monument in 1976.[15] The Tabachka Cave Church, near Tabachka village, adapts prehistoric cave formations for monastic use, featuring early Christian adaptations visible in its rock interior.[16] Finally, the Krepcha Rock Monastery near Krepcha in Targovishte Province, founded around the 10th century during Tsar Simeon the Great's reign, preserves some of the earliest known Cyrillic inscriptions from 921 AD, alongside frescoes and cells in its cliffside setting.[17]Ukraine

Ukraine's cave monasteries, known as lavras, represent a distinctive tradition of large monastic communities centered around extensive underground tunnel networks carved into soft rock formations such as chalk and limestone. These sites, emerging during the Kievan Rus' period, served as centers for ascetic living, prayer, and relic veneration, embodying the spiritual legacy of early Christian hermits who sought isolation in natural caves. The lavra model emphasized communal yet secluded monastic life, with tunnels housing cells, chapels, and burial sites for saints whose incorrupt remains became objects of pilgrimage.[18] The Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra in Kyiv, founded in 1051 by St. Anthony of the Caves and expanded under Theodosius of the Caves, stands as the cradle of East Slavic monasticism and the archetype of the Ukrainian lavra.[19] This UNESCO World Heritage Site features two primary cave systems—the Far Caves and the Near Caves—comprising over 1 kilometer of narrow tunnels (approximately 1-1.5 meters wide and 2-2.5 meters high) that include monk cells, underground churches, and reliquaries containing the mummified remains of more than 70 saints, such as St. Theodosius and St. Varlaam.[18][20] The complex's historical role in Kievan Rus' included fostering Orthodox scholarship, iconography, and resistance to invasions, with its caves symbolizing the enduring ascetic ideal.[21] The Sviatohirsk Lavra, located near Sviatohirsk in the Donetsk region, originated in the 16th century as a cave monastery hewn into chalk hills overlooking the Seversky Donets River, with the first written reference dating to 1526.[22] Its underground features encompass hermitages, churches, and tunnels used for seclusion and worship, forming one of Ukraine's three recognized lavras alongside Kyiv-Pechersk and Pochaiv.[23] The site has endured multiple conflicts, including severe damage during the 2022 Russian invasion that rendered parts unusable, and further shelling on August 15, 2025, which damaged additional structures including the cave complex. Restoration efforts as of November 2025 have focused on preserving the core cave structures amid ongoing challenges, maintaining its spiritual significance.[24][25] In the disputed Crimean region, the Bakhchysarai Cave Monastery (also known as the Assumption or Uspensky Monastery) dates to the 15th century, when monks from Kyiv-Pechersk reportedly established a multi-level complex carved into cliff walls in the Mariam-Dere gorge.[26] The site includes the Assumption Church and interconnected caves serving as cells and chapels, reflecting Byzantine influences in its rock-hewn architecture and icon veneration traditions.[27] Similarly, the Inkerman Cave Monastery near Sevastopol evolved from an 8th-century Byzantine foundation, with expansions continuing through the 19th century, featuring multiple terraced levels in limestone cliffs that house eight chapels, an inn, and tunnels linked to the relics of St. Clement of Rome.[28][29] These Crimean sites underscore the spread of lavra-style monasticism southward, adapting to rugged terrains while maintaining underground ascetic practices.[30]Russia

Cave monasteries in Russia form a significant part of the Eastern Orthodox monastic tradition, sharing roots with Ukraine's ancient lavras through the heritage of Kievan Rus', where hermits first carved cells into rock for ascetic isolation.[31] These sites often emerged in remote landscapes to facilitate solitude and spiritual contemplation, with many dating to the medieval period and enduring through centuries of political upheaval. The 17th-century Old Believer schism, triggered by liturgical reforms under Patriarch Nikon, intensified this trend, as dissenters sought hidden refuges in forests, mountains, and caves to preserve pre-reform rituals away from persecution.[32] Approximately 10-15 such cave complexes exist across Russia, concentrated in northern and border regions, emphasizing seclusion amid challenging terrains like chalk cliffs and dense woodlands.[33] In disputed border regions like Crimea, the Chelter-Koba Monastery near Bakhchysarai features medieval rock-cut cells and a church hewn into cliffs, dating to the 8th-15th centuries and founded by icon-venerating monks escaping Byzantine iconoclasm; the complex includes over 20 caves for living quarters, refectory, and worship, exemplifying early Orthodox adaptation to karst landscapes.[34] Nearby, Chufut-Kale, a cave city near Bakhchysarai, incorporated monastic adaptations from the 5th to 19th centuries, with hermits using natural and excavated cavities for ascetic retreats alongside its fortress structures, blending defensive and spiritual functions in the Crimean Mountains. These sites highlight Russia's cave monasteries as enduring symbols of resilience, tied to the Orthodox pursuit of isolation and faith preservation.Georgia

Georgia's cave monasteries represent a unique fusion of early Christian monasticism and defensive rock-cut architecture, developed in the Caucasus region's arid and volcanic landscapes from the 6th century onward. These complexes, often spanning multiple levels and incorporating churches, living quarters, and halls, served as spiritual retreats, fortresses, and cultural centers during Georgia's medieval Golden Age, reflecting the country's early adoption of Christianity in the 4th century. Prominent examples like Vardzia, David Gareja, and Uplistsikhe highlight this tradition, blending pagan rock-hewn origins with Christian adaptations and featuring ongoing restorations since the post-Soviet era to preserve their frescoes and structures.[35][36][37] Vardzia, located near Aspindza in the Samtskhe-Javakheti region on the left bank of the Mtkvari River, is a 12th-century cave city-monastery complex carved into the slopes of Erusheti Mountain in volcanic rock. Founded during the reign of Queen Tamar as a defensive stronghold against invasions, it originally comprised 641 separate chambers spread across 13 terraced levels, including monk cells, churches, halls, and a throne room, forming a self-contained monastic fortress. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage tentative site since 2007, Vardzia exemplifies medieval Georgian engineering and was partially excavated and restored during the Soviet era, with a small community of monks residing there today to maintain its cultural heritage.[35][38][39][40] The David Gareja Monastery complex, situated in the semi-desert Iori Plateau near the Azerbaijan border in eastern Georgia, dates to the 6th century and consists of 19 interconnected rock-cut monasteries founded by St. David Garejeli, one of the Thirteen Assyrian Fathers who introduced monasticism to the region. Key components include the central Lavra of St. David and the nearby Udabno Monastery, featuring cave churches adorned with well-preserved frescoes from the 8th to 13th centuries depicting biblical scenes, Georgian kings, and the life of St. David. Also on UNESCO's tentative list since 2007, the site endured Mongol invasions and Soviet-era neglect but has seen partial restorations since Georgia's independence in 1991, with active monk communities in several monasteries aiding preservation efforts.[36][41] Uplistsikhe, a rock-hewn town near Gori on the Mtkvari River, originated in the 6th century BC as a pagan political and religious center but was adapted into a Christian cave monastery complex between the 4th and 11th centuries following Georgia's conversion to Christianity. Spanning over 40,000 square meters across three levels with dwellings, halls, and tunnels, it includes a 9th-10th century stone basilica at its summit, marking the site's transition from pagan temple functions—such as sacrifice altars—to Christian worship amid coexisting traditions. This blend of pre-Christian and medieval Christian rock architecture underscores Uplistsikhe's role as a fortified monastic site, with archaeological efforts continuing to highlight its historical layers.[37]Other European countries

Cave monasteries in other European countries, spanning the Balkans, Greece, and select Western locales, embody the adaptation of early Christian eremitic traditions to rugged landscapes, often featuring rock-cut chapels, hermit cells, and cliffside integrations rather than expansive complexes. These sites, predominantly from the early medieval era, served as secluded retreats for monks and sites of pilgrimage, reflecting influences from Byzantine and Orthodox practices while remaining smaller in scale compared to the grand lavras of Eastern Europe. Approximately 20 such locations are documented across these regions, emphasizing their role in preserving ascetic spirituality amid diverse geopolitical shifts. GreeceThe Cave of the Apocalypse on the island of Patmos holds profound religious significance as the traditional site where the Apostle John the Theologian experienced divine visions and dictated the Book of Revelation around 95 AD. This early Christian hermitage, located midway between the ports of Skála and the settlement of Chorá, features small chapels and oratories developed around the natural fissure where John is said to have rested his head. The site integrates seamlessly with the surrounding karst terrain, symbolizing the island's enduring role as a center of Orthodox pilgrimage.[42]

Adjacent to the cave, the Holy Monastery of St. John the Theologian was established in 1088 by the monk Christodoulos under the patronage of Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, incorporating the sacred cavern into its fortified layout. The 11th-century core structures, including the Katholikón church and refectory, evolved over centuries into a castle-like ensemble that protected both monks and refugees during Ottoman rule. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1999 for its architectural and spiritual authenticity, the monastery exemplifies Greek Orthodox continuity in cave-based devotion.[42] North Macedonia

No specific cave monasteries are prominently documented in North Macedonia beyond broader rock-cut church traditions in sites like Zrze and Lesnovo.[43] Romania

The Ostrov Monastery, situated in the Danube cliffs near Călărași, traces its origins to a 10th-century cave church dedicated to St. Andrew the Apostle, who according to tradition preached in the region and used the site as a hermitage. Carved into the sheer bluffs overlooking the Danube, the rock-hewn chapel features ancient frescoes and serves as a focal point for pilgrimage, embodying early Christian evangelization north of the river. The complex expanded in later centuries but retains its core cave structure as a testament to Dobrogea's monastic heritage.[44]

Further north, the Skete of the Cave near Slătiioara, established in the 19th century as a hermitage within the Neamț Mountains, utilizes natural caverns for ascetic cells and prayer spaces, continuing Romania's tradition of sylvan reclusion. Founded by monks seeking solitude, the skete's cave elements support hesychast practices, with paths leading to secluded grottos used for contemplation and small-scale liturgy.[45] Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Zavala Monastery near Mostar integrates cave features into its 13th-century cliffside complex, with the northern wall of the church embedded directly into a karst cave on Ostrog Hill's slope. First documented in 1514 via a founder's seal, the site functioned as a Serbian Orthodox stronghold, its natural cave providing defensive shelter and symbolic depth for monastic life amid regional conflicts. The monastery's architecture merges Byzantine influences with local geology, hosting relics and serving as a pilgrimage hub in Herzegovina's Popovo Field.[46] Albania

In central Albania near Urakë, the Qafthanë Cave Church represents a medieval rock-hewn chapel, carved into a hillside as a secluded worship space during the Byzantine era. Designated a Cultural Monument of Albania, the site features simple excavated interiors suited for early Christian rites, underscoring the persistence of cave veneration in the region's Orthodox communities despite historical upheavals.

Near Shijak, the St. Nicholas Cave Church dates to early Christian times, functioning as a hermitage chapel with rock-cut niches for icons and altars. This modest site, tied to 6th-century monastic migrations, exemplifies Albania's underdocumented cave traditions, offering a quiet testament to pre-Ottoman piety in coastal cliffs. Italy

The Grottaferrata Abbey near Rome, founded in 1004 by St. Nilus of Rossano, derives its name from an ancient "crypta ferrata"—a Roman-era funerary cave sealed with iron grates—incorporating minor cave cells into its Basilian layout. As Italy's sole surviving Italo-Greek monastery, the 11th-century complex preserves Byzantine liturgical practices, with the original cave elements symbolizing the abbey's eremitic roots amid the Alban Hills.[47]