Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chalkidiki

View on Wikipedia

Chalkidiki (/kælˈkɪdɪki/; Greek: Χαλκιδική, romanized: Chalkidikḗ [xalciðiˈci], alternatively Halkidiki), also known as Chalcidice, is a peninsula and regional unit of Greece, part of the region of Central Macedonia, in the geographic region of Macedonia in Northern Greece. The autonomous Mount Athos region constitutes the easternmost part of the peninsula, but not of the regional unit.

Key Information

The capital of Chalkidiki is the town of Polygyros, located in the centre of the peninsula, while the largest town is Nea Moudania. Chalkidiki is a popular summer tourist destination.

Name

[edit]Chalkidiki also spelled Halkidiki (/kælˈkɪdɪki/) or Chalcidice (/kælˈsɪdɪsi/) is named after the ancient Greek city-state of Chalcis in Euboea, which colonised the area in the 8th century BC.

Geography

[edit]

Chalkidiki consists of a large peninsula in the northwestern Aegean Sea, resembling a hand with three 'fingers' (though in Greek these peninsulas are often referred to as 'legs'). From west to east, these are Kassandra (highest peak 345 m), Sithonia (highest peak Mt Itamos 817 m), and Mount Athos, a special polity within Greece known for its monasteries and its highest peak reaching 2,033 metres above sea level. These 'fingers' are separated by two gulfs, the Toronean Gulf and the Singitic Gulf.

Chalkidiki borders on the regional unit of Thessaloniki to the north, and is bounded by the Thermaic Gulf on the west, and the Strymonian Gulf and Ierissos Gulf on the east (which are separated by the Brostomnitsa peninsula).

The Cholomontas mountains lie in the north-central part of Chalkidiki, with the highest peak reaching 1,165 metres above sea level. Chalkidiki has a few rivers running from Mt Cholomontas south to the sea, these include the Havrias, Vatonias (Olynthios) and Psychros rivers. Chalkidiki also has a few islands including the inhabited Ammouliani and Diaporos both in the Singitic Gulf.

Its largest towns are Nea Moudania (Νέα Μουδανιά), Nea Kallikrateia (Νέα Καλλικράτεια) and the capital town of Polygyros (Πολύγυρος).

There are several summer resorts on the beaches of all three fingers where other minor towns and villages are located, such as at Yerakini (Gerakina Beach) and Psakoudia in central Chalkidiki, Kallithea, Chanioti and Pefkochori in the Kassandra peninsula, Nikiti and Neos Marmaras (Porto Carras) in the Sithonia peninsula, and Ouranoupolis at Mount Athos. A popular village in winter is Arnaia for its architecture and mountain scenery.

Climate

[edit]The climate of Chalkidiki is mainly Mediterranean (Koppen: Csa) with cool, wet winters and hot, relatively dry summers. Snowfalls are possible but not long-lasting during the winter months, while occasional thunderstorms may occur during the summer. Few areas such as Neos Marmaras have a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSh).[2][3]

| Climate data for Neos Marmaras 6 m a.s.l. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.7 (69.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

32.4 (90.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

39.9 (103.8) |

41.6 (106.9) |

37.0 (98.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

41.6 (106.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

29.3 (84.7) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.4 (90.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.4 (48.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.4 (59.7) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

18.2 (64.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.2 (24.4) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.2 (39.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 62.4 (2.46) |

28.9 (1.14) |

50.1 (1.97) |

27.4 (1.08) |

21.7 (0.85) |

33.9 (1.33) |

28.0 (1.10) |

11.6 (0.46) |

29.5 (1.16) |

36.8 (1.45) |

41.8 (1.65) |

60.3 (2.37) |

432.4 (17.02) |

| Source: National Observatory of Athens (Feb 2014 – Jul 2024),[4] Neos Marmaras N.O.A station [3] and World Meteorological Organization[5] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]

The first Greek settlers in this area came from Chalcis and Eretria, ancient ionian cities in Euboea, around the 8th century BC who founded cities such as Mende,[6] Toroni and Scione.[7] A second wave came from Andros in the 6th century BC[8] who founded cities such as Akanthos.[9] The ancient city of Stageira was the birthplace of the great philosopher Aristotle. Chalkidiki was an important theatre of war during the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. Later, the Greek colonies of the peninsula were conquered by Philip II of Macedon and Chalkidiki became part of Macedonia (ancient kingdom). After the end of the wars between the Macedonians and the Romans, the region became part of the Roman Empire, along with the rest of Greece. At the end of the Roman Republic (in 43 BC) a Roman colony was settled in Cassandreia, which was later (in 30 BC) resettled by Augustus.[10]

During the following centuries, Chalkidiki was part of the Byzantine Empire (East Roman Empire). On a chrysobull of Emperor Basil I, dated 885, the Holy Mountain (Mount Athos) was proclaimed a place of monks, and no laymen or farmers or cattle-breeders were allowed to be settled there. With the support of Nikephoros II Phokas, the Great Lavra monastery was founded soon afterwards. Athos with its monasteries has been self-governing ever since. Today, over 2,000 monks from Greece and many other Orthodox Christian countries, such as Romania, Moldova, Georgia, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Russia, live an ascetic life in Athos, isolated from the rest of the world.

After a short period of domination by the Latin Kingdom of Thessalonica, the area became again Byzantine until its conquest by the Ottomans in 1430. During the Ottoman period, the peninsula was important for its gold mining. In 1821, the Greek War of Independence started and the Greeks of Chalkidiki revolted under the command of Emmanouel Pappas, a member of Filiki Eteria, and other local fighters. The revolt was progressing slowly and unsystematically. The insurrection was confined to the peninsulas of Mount Athos and Kassandra. One of the main goals was to restrain and detain the coming of the Ottoman army from Istanbul, until the revolution in the south (mainly Peloponnese) became stable. Finally, the revolt resulted in a decisive Ottoman victory at Kassandra. The survivors, among them Papas, were rescued by the Psarian fleet, which took them mainly to Skiathos, Skopelos and Skyros. The Ottomans proceeded in retaliation and many villages were burnt.

Finally, the peninsula was incorporated into the Greek Kingdom in 1912 after the Balkan Wars. Many Greek refugees from East Thrace and Anatolia (modern Turkey) were settled in parts of Chalkidiki after the 1922 Greco-Turkish war, adding to the indigenous Greek population.

In the 1980s, a tourism boom came to Chalkidiki and took over agriculture as the primary industry.[11] In June 2003, at the holiday resort of Porto Carras located in Neos Marmaras, Sithonia, leaders of the European Union presented the first draft of the European Constitution (see History of the European Constitution for developments after this point).

Ancient sites

[edit]

- Acanthus (near Ierissos)

- Acrothoi

- Aege

- Alapta

- Aphytis (Afytos)

- Apollonia (near Polygyros)

- Cleonae (Chalcidice)

- Galepsus

- Mekyberna

- Mende

- Neapolis, Chalcidice

- Olophyxus

- Olynthus

- Palaiochori "Neposi" castle

- Polichrono

- Potidaea

- Scione

- Scolus

- Sermylia (Ormylia)

- Stageira

- Spartolus

- Thyssus

- Torone

- Treasury of the Acanthians

- Xerxes Canal

Archaeology

[edit]In June 2022, archaeologists announced the discovery of a poorly preserved single-edged sabre among the ruins of a monastery on the coast of Chalcidice. Alongside the curved sword, excavators revealed evidence of a fire, a large cache of 14th-century glazed pottery vessels, as well as other weapons, including axes and arrowheads.[12]

Economy

[edit]Agriculture

[edit]The peninsula is notable for its olive oil and its green olives production. Also various types of honey and wine are produced.

Tourism

[edit]Chalkidiki has been a popular summer tourist destination since the late 1950s when people from Thessaloniki started spending their summer holidays in the coastal villages. In the beginning tourists rented rooms in the houses of locals. By the 1960s, tourists from Austria and Germany started to visit Chalkidiki more frequently. Since the start of the big tourist boom in the 1970s, the whole region has been captured by tourism.[13] In the region there is a golf course, with plans for four others in the future.

Mining

[edit]Gold was mined in the region during antiquity by Philip II of Macedon and the next rulers. Since 2013, a revival of mining for gold and other minerals has occurred, and a number of concessions have been granted to Eldorado Gold of Canada. Critics claim that mining adversely affects tourism and the environment.[14] Plus, the movement took panhellenic and international affection in the name of "Chalkidiki SOS" with major strikes and protests at European capitals during the years.[15]

Administration

[edit]The Chalkidiki regional unit is subdivided into five municipalities (numbered as in the infobox map):[16]

- Aristotelis (2)

- Kassandra (4)

- Nea Propontida (3)

- Polygyros (1)

- Sithonia (5)

Prefecture

[edit]As a part of Greece's 2011 local government reform, the Chalkidiki regional unit (περιφερειακή ενότητα, perifereiakí enótita) was created out of the former Chalkidiki prefecture (νομός, nomós); the regional unit has the same territory as the former prefecture. As part of the reforms, Chalkidiki's five municipalities (δήμοι, dhími) were created by combining former municipalities, which were in turn demoted to municipal units (δημοτικές ενότητες, dhimotikés enótites), according to the table below.[16]

| Municipalities | Municipal Units[a] | Seat |

|---|---|---|

| Aristotelis | Arnaia | Ierissos |

| Panagia | ||

| Stagira-Akanthos | ||

| Kassandra | Kassandra | Kassandreia |

| Pallini | ||

| Nea Propontida | Kallikrateia | Nea Moudania |

| Moudania | ||

| Triglia | ||

| Polygyros | Polygyros | Polygyros |

| Anthemountas | ||

| Zervochoria | ||

| Ormylia | ||

| Sithonia | Sithonia | Nikiti |

| Toroni |

Provinces

[edit]Before the abolishment of the provinces of Greece in 2006, the Chalkidiki prefecture was subdivided into the following provinces:[17]

| Province | Seat |

|---|---|

| Arnaia Province | Arnaia |

| Chalkidiki Province | Polygyros |

Population

[edit]The autonomous monastic state of Mount Athos which is often considered to be geographically part of Chalkidiki recorded an additional 1,746 people in the 2021 census. The population is mostly Orthodox Christian monks.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1991[18] | 85,471 | — |

| 2001[18] | 96,849 | +13.3% |

| 2011[18] | 105,908 | +9.4% |

| 2021[1] | 102,085 | −3.6% |

Television

[edit]- TV Halkidiki – Nea Moudania

- Super TV – Nea Moudania

Transport

[edit]- Motorways:

- A24 motorway connects Thessaloniki and "Macedonia" Airport with Nea Moudania and Kallithea in Kassandra.

- Chalkidiki has no railroads or airports.

- A bus system, KTEL, serves major towns.

In September 2018 it was announced that Line 2 of the Thessaloniki Metro could be extended in the future in order to serve commuters to and from some areas of Chalkidiki.[19]

Notable inhabitants

[edit]

- Paeonius of Mende (late 5th century BC), sculptor

- Philippus of Mende, Plato's student, astronomer

- Nicomachus, Aristotle's father

- Aristobulus of Cassandreia (375–301 BC), historian, architect

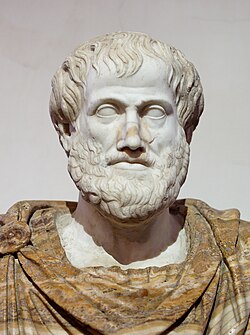

- Aristotle (384 BC in Stageira–322 BC), philosopher

- Andronicus of Olynthus (c. 370 BC), Phrourarchus of Tyre, appointed by Antigonus

- Callisthenes (360–328 BC), historian

- Crates of Olynthus, Alexander's hydraulic engineer

- Bubalus of Cassandreia (304 BC), keles (horse) competing in the flat race of the Lykaia[20]

- Poseidippus of Cassandreia (c. 310–240 BC), comic poet

- Erginus (son of Simylus) from Cassandreia, citharede winner in Soteria c. 260 BC[21]

- Konstantinos Doumbiotis (1793-1848), revolutionary of the Greek War of Independence

- Stamatios Kapsas, revolutionary of the Greek War of Independence

- Xenophon Paionidis (1863–1933), architect

- Manolis Mitsias, singer

- Sokratis Malamas (1957 in Sykia), singer

- Paola Foka (1982 Sykia), singer[22]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Prior to the implementation of the Kallikratis Plan these municipal units were municipalities.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Αποτελέσματα Απογραφής Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2021, Μόνιμος Πληθυσμός κατά οικισμό" [Results of the 2021 Population - Housing Census, Permanent population by settlement] (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 29 March 2024.

- ^ Petrou, Alec Moustris, John. "meteo.gr – Προγνώσεις καιρού για όλη την Ελλάδα". meteo.gr – Προγνώσεις καιρού για όλη την Ελλάδα (in Greek). Retrieved 23 January 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Latest Conditions in Neos Marmaras". penteli.meteo.gr. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ "N.O.A Monthly Bulletins".|source 2=

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization". Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Thucydides, Book 4, 123

- ^ N. G. L. Hammond, A History of Macedonia, Vol. 1: Historical Geography and Prehistory (Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 426.

- ^ The Cyclades: Discovering the Greek Islands of the Aegean By John Freely p. 82

- ^ Thucydides, Book 4, p. 84

- ^ [1] Archived 24 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine D. C. Samsaris,The Roman Colony of Cassandreia in Macedonia (Colonia Iulia Augusta Cassandrensis) (in Greek), Dodona 16(1), 1987, 353–437

- ^ "THE HISTORY OF KASSANDRA, HALKIDIKI!!". Transfer Thessaloniki. 18 March 2018. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Tom Metcalfe (7 June 2022). "Rusty saber, possibly wielded by medieval Turkish pirates, unearthed in Greece". livescience.com. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Deltsou, Eleftheria (2007). "Second homes and tourism in a Greek village". Ethnologia Europaea: Journal of European Ethnology. 37 (1–2): 124.

- ^ Suzanne Daley (13 January 2013). "Greece Sees Gold Boom, but at a Price". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "Σκουριές: Ένταση στην πορεία κατά της εξόρυξης χρυσού".

- ^ a b "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- ^ "Detailed census results 1991" (PDF). (39 MB) (in Greek and French)

- ^ a b c "Απογραφές πληθυσμού 1991,2001,2011 σύμφωνα με την κωδικοποίηση της Απογραφής 2011" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "ΑΤΤΙΚΟ ΜΕΤΡΟ: "Το Μέτρο στη πόλη μας" με το πρώτο του βαγόνι. Συμμετοχή της Αττικό Μετρό Α.Ε. στην 83η Δ.Ε.Θ." [Attiko Metro: "The Metro in our city" with the first carriage. The participation of Attiko Metro S.A. at the 83rd Thessaloniki International Fair]. www.ametro.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ Arkadia – Lykaion – Epigraphical Database

- ^ Phocis – Delphi – Epigraphical Database

- ^ "Xronia Polla Paola Foka, Who Turns 38 Today". Greek City Times. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

External links

[edit] Media related to Chalkidiki at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chalkidiki at Wikimedia Commons

Chalkidiki

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name origins and variations

The name Chalkidiki (Greek: Χαλκιδική) originates from the ancient Chalcidians (Χαλκιδεῖς), a group of Greek colonists primarily from the city of Chalcis (modern Chalkida) on the island of Euboea, who established numerous settlements across the peninsula during the 8th and 7th centuries BCE as part of the broader Archaic period colonization of the northern Aegean.[8] [9] These settlers, often referred to as the "Chalcidian tribe" or "Chalcidians in Thrace," formed a network of city-states that gave the region its collective identity, with the name reflecting the ethnic and political dominance of these Euboean migrants over indigenous Thracian populations.[8] The term itself may imply "land of the Chalcidians" or adherence to Chalcidian customs, as suggested by interpretations linking it to the practices imported from their homeland.[10] While the root chalkos (χαλκός, meaning "copper" or "bronze" in ancient Greek) underlies the name of Chalcis—possibly alluding to bronze-working traditions there—the application to Chalkidiki stems directly from the colonists' ethnic designation rather than local metallurgy, as no significant copper deposits or mining evidence exist in the peninsula to support an independent mineral-based etymology.[11] Ancient sources, such as Herodotus, describe the inhabitants as a "Chalcidian genos" (tribe or race) of Greek origin, distinguishing them from Thracians and emphasizing their role in shaping the region's Hellenic character from the 6th century BCE onward.[8] Historical variations include the ancient form Chalkidikē (Χαλκιδική), used in classical texts to denote the peninsula and its peoples, often Latinized as Chalcidice in Roman and medieval scholarship to evoke the tripartite geography and colonial heritage.[12] In modern usage, transliterations diverge: the standard Greek Chalkidikí predominates in official contexts, while anglicized forms like Halkidiki (reflecting phonetic shifts) or the classical Chalcidice appear in English-language historical and touristic references, with Chalcidice preserving the "ch" aspirate closer to ancient pronunciation.[11] These variants emerged from evolving orthographic conventions, with Halkidiki gaining traction in mid-20th-century international media but criticized by some philologists for diluting the original kh sound (χ).[11] No pre-Greek or Thracian substrate names for the peninsula are attested, underscoring the enduring impact of Chalcidian nomenclature.[8]Geography

Physical landscape and peninsulas

Chalkidiki occupies a total land area of 2,886 square kilometers in northern Greece, forming a large peninsula that juts into the northwestern Aegean Sea and is divided into three smaller peninsulas extending southward like fingers: Kassandra to the west, Sithonia in the center, and Athos (Akti) to the east. The region's physical landscape combines rugged mountainous interiors with rolling hills, dense forests, and over 500 kilometers of indented coastline featuring numerous bays and beaches. This topography arises from tectonic uplift and erosion processes shaping the Macedonian geological block, resulting in varied elevations from sea level to peaks exceeding 2,000 meters.[13][6] The central upland is anchored by Mount Holomontas (also Cholomon), a range stretching southwest-northeast from near Polygyros to Arnaia, with its highest peak at 1,165 meters northeast of the regional capital. Covered in mixed deciduous and coniferous forests including oak, chestnut, fir, and broadleaf species, Holomontas supports diverse flora and provides watershed drainage to surrounding valleys and coastal plains. These forests, interspersed with meadows, contribute to the area's biodiversity and moderate local microclimates through evapotranspiration and soil stabilization.[14][15][16] Kassandra Peninsula, approximately 60 kilometers long and up to 20 kilometers wide at its base, features gentler terrain with maximum elevations around 345 meters, dominated by low hills and fertile plains suitable for agriculture amid olive groves and vineyards. Sithonia, similarly elongated but narrower, rises to more pronounced relief with Mount Itamos at 817 meters, its central spine fostering steeper slopes, deeper valleys, and forested highlands that transition to pine-clad shores. Athos Peninsula culminates in the prominent Mount Athos peak at 2,033 meters, the highest point visible across much of Chalkidiki, its steep, rocky flanks and autonomous monastic terrain preserving ancient erosional features and limited arable land.[13][17][18]Climate patterns

Chalkidiki features a hot-summer Mediterranean climate classified as Csa under the Köppen-Geiger system, with pronounced seasonal contrasts driven by its coastal position and topographic diversity. Summers from June to August are hot and arid, with average high temperatures reaching 30°C in July and minimal precipitation, typically 1–2 rainy days per month and negligible rainfall totals. Winters from December to February are mild but wetter, featuring average highs of 11–12°C, lows around 6°C in January, and 9–12 rainy days monthly, accounting for the bulk of the region's approximately 566 mm annual precipitation. Spring and autumn serve as transitional periods, with rising or falling temperatures and moderate rainfall.[20] Sunshine duration peaks in summer at 12–13 hours daily, dropping to 4–5 hours in winter, supporting extended daylight for tourism but also heightening fire risk during dry spells. Sea surface temperatures align with air patterns, warming to 24–25°C in July–August for ideal swimming conditions and cooling to 15–16°C in winter. Annual average temperatures hover around 17°C, reflecting the moderating influence of the Aegean and Thermaic Gulfs.[20][21] Regional variations arise from the peninsula's tripartite structure and elevation gradients. Coastal zones on Kassandra and Sithonia peninsulas maintain milder conditions year-round due to maritime influences, while inland areas and the Holomontas Mountains in northern Chalkidiki experience cooler winters with occasional snowfalls and frost, potentially dropping below 0°C at higher altitudes. Mount Athos, the easternmost prong, deviates slightly from the standard Mediterranean regime of the western peninsulas, with potentially increased humidity and precipitation influenced by its forested slopes and exposure to northerly winds. These patterns underscore the role of orographic effects and sea breezes in local microclimates.[22][23][24]Biodiversity and protected regions

Chalkidiki's biodiversity is characterized by a mix of Mediterranean and sub-Mediterranean ecosystems, supporting diverse flora and fauna across its forested mountains, wetlands, and coastal zones. The peninsula hosts extensive oak and beech forests at lower elevations, transitioning to fir and pine stands higher up, with broad-leaved species predominant in areas like the Taxiarchis forest.[25] Fauna includes mammals such as deer, wild boars, hares, wolves, foxes, martens, and badgers, alongside reptiles, amphibians, birds, and marine species in coastal habitats.[26] The region's varied terrain contributes to habitats for endemic and rare species, with the Halkidiki peninsula recognized as rich in protected plants, animals, and ecosystems.[27] Mount Athos, the easternmost peninsula, stands out for its exceptional biodiversity, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988 for both cultural and natural values. It features at least 35 endemic plant species, primarily in alpine zones, with forests of black pine (Pinus nigra), oak, and cedar, alongside sub-alpine and semi-desert vegetation.[4] [28] The area serves as a biodiversity hotspot in the South Balkans, with monastic conservation practices aiding preservation.[29] Much of Chalkidiki's natural landscape falls under the EU Natura 2000 network, encompassing 12 protected sites focused on natural beauty and biodiversity conservation. Key wetlands include the Agios Mamas Lagoon, a Special Protection Area (code GR1270004) supporting unique aquatic and avian species, and Mavrobara Lake, declared a protected natural monument in 1997 and home to rare Emydidae turtles.[30] [25] [31] These designations prioritize habitat protection amid tourism and development pressures, with Mount Athos functioning as a de facto nature reserve due to restricted access and traditional land management.[32]History

Prehistoric settlements and ancient Greek era

The Petralona Cave in Chalkidiki preserves evidence of early hominid occupation dating back over one million years, including traces of controlled fire use around 1,000,000 years ago.[33] Discovered in 1959 near the village of Petralona, the cave spans approximately 10,400 square meters and contains stalactites, stalagmites, and fossils from 22 animal species such as prehistoric bears and lions.[34] In 1960, excavators uncovered a fossilized archaic human skull, initially dated to 700,000 years old and classified as Archanthropus europaeus petraloniensis, suggesting one of Europe's earliest hominid remains.[35] Subsequent analyses have revised the skull's age to about 300,000 years, identifying it as neither Homo sapiens nor Neanderthal but possibly an early Homo heidelbergensis or related form, challenging timelines of human migration into Europe.[36] Archaeological evidence indicates sporadic Paleolithic activity across Chalkidiki, though systematic settlements appear limited until later periods; the region's karstic landscape likely facilitated cave-based habitation by mobile hunter-gatherers.[37] Chalkidiki, anciently termed Chalcidice, saw Greek colonization from the 8th century BC onward, with settlers from Euboea (Chalcis and Eretria), Corinth, and Andros establishing poleis amid indigenous Thracian tribes like the Sithonians. Key foundations included Potidaea around 600 BC by Corinthians on the Pallene isthmus, leveraging its strategic harbor for trade and defense. Stagira, colonized circa 655 BC by Andrians on the eastern coast, prospered as an independent city until the Persian Wars and later became renowned as the birthplace of philosopher Aristotle in 384 BC.[38] Olynthus, originally inhabited by Bottiaeans, emerged as a Greek center in the 5th century BC, situated on hills overlooking the Torone Gulf.[39] In 432 BC, amid tensions with Athens, Chalcidian cities formed a league under Olynthus' leadership, rebelling against Athenian tribute demands; this sparked the Battle of Potidaea, where Corinthian and Potidaean forces clashed with Athenians, escalating into the Peloponnesian War.[39] During Xerxes' invasion in 480 BC, many Chalcidian poleis submitted to Persia, facilitating the Persian advance through Thrace.[40] The league expanded in the 4th century BC but faced Macedonian pressure; Philip II conquered Potidaea in 356 BC and razed Olynthus in 348 BC after diplomatic failures, incorporating Chalcidice into Macedon.[41] Aristotle, after tutoring Alexander the Great, reportedly influenced the rebuilding of Stagira, underscoring the region's ties to Macedonian intellectual and political spheres.[42]Byzantine, Ottoman, and early modern periods

Following the Fourth Crusade, Chalkidiki fell briefly under Latin rule as part of the Kingdom of Thessalonica from 1204 until its reconquest by the Byzantine Empire under Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1261, restoring imperial administration centered on Thessaloniki.[43] The region's strategic proximity to the capital and its monastic centers, particularly Mount Athos, enhanced its significance within the empire's ecclesiastical and economic framework from the 9th to 15th centuries.[44] Mount Athos emerged as a pivotal spiritual hub during this era, with organized monasticism solidifying in the 10th century under imperial patronage. Emperor Basil I issued a decree in 883 prohibiting women from the peninsula, while John I Tzimiskes granted the first constitutional charter in 972, regulating the community and confirming land grants to monasteries like the Great Lavra, founded in 963 by Athanasius the Athonite.[4] [45] Byzantine emperors in the 10th and 11th centuries provided sustained financial and territorial support, enabling rapid expansion to over 180 monastic establishments by the 12th century and fostering intellectual centers that preserved Greek Orthodox traditions.[46] The 14th-century hesychast controversy, championed by Gregory Palamas against rationalist critics, further elevated Athos as a defender of mystical theology, influencing broader Byzantine religious debates.[47] Beyond Athos, Byzantine-era structures like the 14th-century tower at Zografou Monastery and various churches dotted the peninsula, reflecting defensive and devotional architecture amid Slavic incursions and imperial oversight.[48] The Ottoman conquest of Chalkidiki occurred in stages, beginning with Sultan Murad I's victory at the Battle of Chortiatis in 1384, followed by a brief Byzantine recovery until reconquest in 1423 and the definitive fall of Thessaloniki in 1430 under Murad II.[49] [50] Sultans promptly affirmed Mount Athos's privileges through firmans, granting autonomy, tax exemptions on monastic lands, and protection from non-Orthodox settlement, allowing the community to function as a semi-independent entity and cultural bastion under Ottoman suzerainty.[51] This status, renewed by subsequent rulers including Mehmed II after 1453, preserved Byzantine administrative and spiritual continuity despite periodic impositions like the devshirme tribute until its abolition in the 17th century.[52] During the Ottoman centuries, encompassing the early modern period for the region, Chalkidiki's economy centered on agriculture, olive oil production, and mining—especially gold and silver—which intensified environmental pressures such as deforestation for smelting and agricultural expansion.[53] Monasteries, including those on Athos, played a key role in sustaining Greek Orthodox identity, education, and manuscript preservation amid Islamization policies elsewhere, though the peninsula saw demographic shifts with some conversions and migrations.[54] In 1821, amid the Greek War of Independence, local revolutionaries under leaders like Emmanouil Pappas, backed by Athonite monks, launched uprisings across Kassandra and Sithonia peninsulas starting in May, capturing Polygyros and staging guerrilla actions; however, Ottoman forces under Yusuf Pasha suppressed the revolt by autumn, executing leaders and razing villages in reprisal.[55] These events underscored persistent resistance but delayed integration into independent Greece until the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 transferred the territory definitively.[7]20th-century events and post-independence developments

Chalkidiki was incorporated into the Kingdom of Greece following the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, marking the end of Ottoman control over the peninsula.[56][43] Prior to this, in the early 1900s, local inhabitants actively participated in the Macedonian Struggle, a guerrilla campaign against Ottoman forces to secure Greek influence in Macedonia, with fighters from Chalkidiki villages joining efforts led by figures such as Pavlos Melas.[7][57] During World War II, Chalkidiki came under Axis occupation in April 1941 after German forces invaded Greece, with Thessaloniki and the peninsula falling under Nazi control shortly thereafter; German troops were stationed on Mount Athos by mid-1941, enforcing restrictions on monastic communities while the broader region endured requisitions, forced labor, and resistance activities.[58] The occupation ended in October 1944 as Allied advances and Greek resistance liberated northern Greece, though the area subsequently faced disruptions from the Greek Civil War (1946–1949), during which communist guerrillas operated in rural Macedonian regions including parts of Chalkidiki.[59] Post-war reconstruction emphasized economic diversification, with agriculture and forestry remaining staples until the mid-20th century tourism surge; by the 1970s, following the fall of the military junta in 1974, the Greek government secured World Bank funding for large-scale resort developments in Chalkidiki, particularly on the Kassandra peninsula, spurring infrastructure growth and transforming the region into a major Mediterranean destination reliant on seasonal visitors.[60] This shift accelerated in the late 20th century through EU-supported initiatives like LEADER programs, which promoted rural tourism in inland areas while preserving traditional villages amid rapid coastal commercialization.[61]Archaeology

Major excavation sites

Ancient Olynthus, located east of the modern village of Olynthos, represents one of the most extensively excavated classical Greek cities in Chalkidiki, with systematic digs conducted by the American School of Classical Studies from 1928 to 1938 under David M. Robinson.[62] These excavations uncovered over 100 houses arranged in an orthogonal grid plan, advanced for the 5th-4th centuries BCE, along with well-preserved pebble mosaics depicting mythological scenes, such as the abduction of Europa, dating to around 400-350 BCE.[63] The site, originally settled by Bottiaean tribes and refounded by Chalkidian Greeks in the 7th century BCE, peaked as a major urban center before its destruction by Philip II of Macedon in 348 BCE, yielding artifacts now housed primarily in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki.[64] Petralona Cave, situated in the foothills of Mount Katsika near the village of Petralona, is a key Paleolithic site discovered accidentally in 1959 by locals and systematically excavated starting in 1968 by anthropologist Aris Poulianos.[65] Excavations have revealed over 160,000 animal fossils, stone tools, and hearths indicating human presence from at least 700,000 years ago, with the partial cranium of Homo heidelbergensis (Petralona skull), unearthed in 1960, dated through thermoluminescence and uranium-series methods to approximately 200,000-160,000 years BCE, though dating remains subject to ongoing debate among paleoanthropologists.[66] The cave's stratigraphy also includes evidence of continuous occupation through the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, with finds displayed in an adjacent museum established in 1977.[33] Ancient Stagira, perched on a promontory near modern Olympiada, has been excavated since the 20th century, revealing fortifications, temples, and residential areas of a city founded around 655 BCE by Andrian colonists.[38] The site, best known as the birthplace of philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE), includes a 4th-century BCE acropolis wall circuit exceeding 2 kilometers in length, sanctuaries dedicated to Zeus and Athena, and a theater, with digs by Greek authorities uncovering pottery and inscriptions linking it to Macedonian influence after Philip II's annexation in 379 BCE.[63] Restoration efforts since the 1990s have emphasized its role in classical urbanism and defense.[42] The archaeological site of Potidaea, at the isthmus of the Kassandra peninsula near Nea Potidaea, features remains of a Corinthian colony established circa 600 BCE, with excavations exposing the Hellenistic diateichisma—a 3.5-kilometer fortification wall constructed by Cassander around 316 BCE to control peninsula access, complete with towers and gates.[67] Earlier classical layers include temple foundations and harbor structures tied to the city's role in the Peloponnesian War, where it rebelled against Athenian control in 432 BCE, leading to a prolonged siege until its surrender in 430 BCE.[68] Limited systematic digs, supplemented by surface surveys, highlight its strategic canal linking the Thermaic Gulf to the Toronean Gulf, operational from antiquity.[64]Key discoveries and their implications

The Petralona Cave in Chalkidiki yielded a hominin cranium in 1960, recently dated via U-series methods to a minimum age of 286,000 years, placing it among the oldest known Eurasian hominin fossils.[69] This specimen exhibits primitive traits distinct from both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, suggesting affiliation with an early, non-Neanderthal Homo lineage that persisted in Europe.[70] Accompanying stone tools from the cave, dated to approximately 700,000 years ago, indicate Acheulean technology use by pre-Neanderthal populations, extending the timeline of hominin presence in southeastern Europe and challenging models of a singular African exodus for modern humans.[71] Excavations at Olynthus, the ancient capital of the Chalcidian League, uncovered a grid-planned urban layout from the 5th-4th centuries BCE, including over 100 houses with pebble mosaics, cisterns, and infrastructure reflecting Hippodamian principles adapted to Macedonian contexts.[63] Finds from Late Neolithic layers (5300-4500 BCE) include pottery and structures, evidencing early sedentary communities in northern Greece, while classical artifacts illuminate daily life, trade, and the city's destruction by Philip II in 348 BCE.[64] These discoveries underscore Chalkidiki's role as a hub of Greek city-state federation and cultural exchange, providing material evidence for Demosthenes' orations against Macedonian expansion. At Stageira, birthplace of Aristotle in 384 BCE, archaeological work has revealed classical fortifications, an acropolis, and Byzantine overlays on a site founded around 655 BCE by Andrian colonists.[72] Though artifact yields are modest compared to Olynthus, the site's preservation of urban defenses and public spaces highlights northern Greek resilience against Persian and internal conflicts, with implications for understanding philosophical centers in peripheral poleis.[73] Collectively, these findings affirm Chalkidiki's stratigraphic depth, from Paleolithic migrations to classical urbanization, informing debates on hominin dispersal routes and the socio-political dynamics preceding Alexander's empire, though debates persist on Petralona's exact taxonomic placement due to morphological ambiguities.[36]Administration and governance

Regional divisions and local government

Chalkidiki forms a regional unit (perifereiakí enótita) within the Region of Central Macedonia, a second-level administrative division established by the Kallikratis Programme enacted on 1 January 2011, which consolidated Greece's local government by merging 1,033 municipalities and communities into 325 larger units and eliminating the intermediate prefectural tier.[74] This reform aimed to enhance administrative efficiency and fiscal management amid economic pressures, reducing fragmentation while devolving powers to municipalities for services like infrastructure, social welfare, and environmental protection.[75] The Chalkidiki regional unit encompasses five municipalities: Aristotelis (seat: Stagira-Arnaia), Kassandra (seat: Kassandra), Nea Propontida (seat: Nea Moudania), Polygyros (seat: Polygyros), and Sithonia (seat: Nikiti).[3] Polygyros serves as the administrative capital of the regional unit, hosting key offices for coordination with the regional authority.[76] These municipalities cover the peninsula's three prongs—Kassandra, Sithonia, and the mainland extensions—excluding the autonomous monastic community of Mount Athos, which maintains distinct governance.[3] Local government operates primarily through these elected municipalities, each led by a mayor and a council of 13 to 49 members depending on population, elected every five years via proportional representation with a reinforced majority for the leading list.[75] The most recent municipal elections occurred on 8 October 2023, determining leadership until 2028.[74] Municipalities exercise autonomy in budgeting, taxation (primarily local fees), and policy execution, supervised by the Ministry of Interior, while regional units facilitate inter-municipal coordination without independent elected bodies, falling under the elected governor of Central Macedonia.[75] This structure emphasizes decentralized service delivery, with Chalkidiki's municipalities focusing on tourism regulation, coastal management, and rural development.[3]| Municipality | Seat | Key Areas Covered |

|---|---|---|

| Aristotelis | Stagira-Arnaia | Eastern Chalkidiki, near Athos |

| Kassandra | Kassandra | Western peninsula (Pallene) |

| Nea Propontida | Nea Moudania | Northern coastal and inland |

| Polygyros | Polygyros | Central inland and administrative |

| Sithonia | Nikiti | Middle peninsula (Longos) |

Mount Athos autonomous status

Mount Athos possesses a unique autonomous status within the Hellenic Republic, functioning as a self-governing monastic polity under Greek sovereignty. This arrangement, rooted in historical privileges dating to the Byzantine era, is constitutionally enshrined in Article 105 of the Greek Constitution, which stipulates that Mount Athos shall be divided among its twenty Holy Monasteries for governance purposes, with the validity of state-granted privileges preserved and the administrative regime linked to the Ecumenical Patriarchate maintained.[77][78] The peninsula's autonomy encompasses internal monastic affairs, including the regulation of religious life, property management, and community decisions, while external matters such as defense, foreign relations, and fiscal oversight remain under Greek state authority.[79] The legal framework was formalized post-Greek independence through a 1924 Charter drafted by a committee of prominent Athonite monks, which outlined administrative structures and privileges, followed by Greek Law 530 of 1926 that codified the status and affirmed national sovereignty over the territory.[79] Governance is exercised by the Holy Community of Mount Athos (Iera Koinotita Agiou Orous), a representative body comprising abbots or delegates from the twenty monasteries, operating through key institutions: the Protos (the senior monk serving as spiritual leader), the Quadriennial Holy Epistasia (an executive council elected every four years to handle daily administration from the capital at Karyes), the Hieromonastic Synaxis (a legislative assembly of monastic superiors), and the Pentad (a judicial body for internal disputes).[80][81] The Greek state interfaces via a Civil Governor, appointed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and residing in Karyes, who supervises secular functions like customs, police, and infrastructure without interfering in monastic autonomy.[81] This special status extends to exemptions from certain national laws, such as those on gender equality and EU acquis in areas like agriculture and fisheries, justified by the community's exclusively male monastic character and avaton rule prohibiting female entry, a tradition upheld since at least the 11th century and protected constitutionally to preserve spiritual integrity.[82] Mount Athos's integration into the European Union follows Protocol 10 annexed to the 1992 Treaty on European Union, recognizing its distinct regime while ensuring fundamental rights alignment, though it opts out of the eurozone and Schengen Area implementation.[83] As of 2025, the administration reflects rotational leadership among monasteries, with the Monastery of Great Lavra assuming the Epistasia presidency in June following elections.[84]Economy

Agriculture and primary production

Chalkidiki's agriculture centers on olive cultivation, which dominates primary production due to the region's Mediterranean climate and extensive groves spanning approximately 225,000 square meters of dedicated land. The Chalkidiki olive variety, prized for its large size and green table olives, accounts for nearly 50% of Greece's national table olive output, with annual production fluctuating between 80,000 and 120,000 metric tons in favorable years. [85] Approximately 92% of these olives are exported, primarily to markets in Europe and beyond, generating significant revenue while the remainder supports local processing into olive oil at around 7,000 tons annually. [86] This focus on table olives, rather than oil extraction for export, stems from the cultivar's fleshy characteristics, which yield higher flesh-to-pit ratios but command premium prices due to labor-intensive harvesting and processing.[87] Fruit orchards contribute substantially to the local economy, particularly in inland and foothill areas like Polygyros and Portaria, where apricots, peaches, cherries, and strawberries thrive on well-drained soils. Apricots from Portaria are especially renowned for fresh consumption, preserves, and marmalades, reflecting the region's microclimates that support diverse pomology.[88] Vegetable production, including tomatoes and peppers, occurs on smaller scales in fertile plains near Nea Moudania, supplementing household and local markets amid tourism-driven demand. Beekeeping leverages Chalkidiki's flora, including thyme meadows and pine forests in Cholomontas, yielding high-quality honeys such as thyme and pine varieties, though exact production volumes remain modest compared to olives and integrated into broader Macedonian apiculture trends.[89] Livestock rearing, primarily sheep and goats for dairy and meat, is limited by terrain but supports cheese production like sagánaki precursors, with pastoral activities concentrated in upland villages. Fisheries along the peninsula's extensive coastline provide supplementary primary output, focusing on Aegean species like sea bream, though volumes are dwarfed by agronomic sectors and subject to EU quotas. Climate variability, including mild winters reducing fruit set, poses risks to olive and fruit yields, as evidenced by suboptimal harvests in recent years.[90] Overall, while agriculture employs a shrinking share of the workforce amid urbanization, it sustains rural viability and underpins PDO-protected products like Agourelio Chalkidikis olives.[91]Mining operations and resource extraction

The Kassandra Mines district in northeastern Chalkidiki has hosted mining activities for metallic ores since antiquity, with archaeological evidence indicating gold and silver extraction dating back to the 6th century BC, yielding an estimated 33 million tons of gold over millennia.[92] In the modern era, operations focus on polymetallic deposits containing gold, copper, lead, zinc, and associated minerals such as pyrite, chalcopyrite, sphalerite, and argentite, with ore grades varying by deposit but including high gold concentrations in certain zones.[93] Hellas Gold S.A., a subsidiary of Eldorado Gold Corporation, manages the primary metallic mining operations under EU environmental and safety regulations, including the Olympias underground mine and the developing Skouries open-pit project.[94] [95] The Olympias mine, reactivated in 2011 after historical intermittent use, achieved commercial production in December 2017, extracting refractory gold ore alongside lead and zinc concentrates through underground methods and processing via flotation and bio-oxidation.[96] As of 2023, mineral reserves at Olympias supported ongoing extraction scheduled for progressive depletion.[96] The Skouries project targets a high-grade copper-gold porphyry deposit, with Phase 2 construction 78% complete as of December 31, 2025 (overall progress 90% including Phase 1); first copper-gold concentrate production is expected toward the end of Q1 2026, followed by commercial operations in mid-2026, with permitting proceeding without noted issues in recent disclosures.[97] This will yield an average of 140,000 ounces of gold and significant copper annually over an initial 20-year mine life.[98] [99] Detailed engineering and procurement for Skouries were substantially complete by late 2024, with phase 2 advancements including infrastructure for concentrate export.[100] Industrial mineral extraction includes magnesite mining by Grecian Magnesite, with operations tracing to 1914 and formalized in 1959, involving open-pit methods followed by enrichment processes to separate magnesite from associated minerals.[101] Greece's magnesite production, partly from Chalkidiki sources, positions it as a regional leader, though specific local output figures remain integrated into national aggregates.[102] Additional by-product recovery, such as antimony at Olympias separation facilities, supports value extraction from polymetallic tailings.[103]Tourism, real estate, and service sectors

Tourism constitutes the dominant economic driver in Chalkidiki, particularly along the Kassandra and Sithonia peninsulas, where sandy beaches, pine forests, and luxury resorts attract seasonal visitors. In 2024, Halkidiki recorded strong inbound demand, with Google searches rising 10.5% over 2023 levels and domestic Greek visitors comprising nearly 20% of total arrivals, followed by the United Kingdom at 16.3% and Germany at 10.3%.[104] British pre-bookings for 2024 surged 18% year-over-year, reflecting robust recovery and expansion beyond pre-pandemic figures, as evidenced by airline data showing 24% growth compared to 2019.[105] The sector's seasonality confines peak activity to summer months, contributing to employment volatility, with a 2025 survey indicating nearly 40% of tourism businesses still facing acute staff shortages despite overall economic strengthening in late summer.[106] High-end developments, such as the Sani Resort and Porto Carras complex, underscore Chalkidiki's shift toward upscale, all-inclusive offerings, which saw a 444% national increase in bookings for Greece in 2024, amplifying local revenue through extended stays and premium services.[107] This growth aligns with national trends, where tourism directly contributed €30.2 billion or 13% to Greece's GDP in 2024, with Chalkidiki benefiting from its proximity to Thessaloniki and appeal to regional drive-in tourists from neighboring countries.[108] Real estate in Chalkidiki has experienced accelerated demand fueled by tourism infrastructure and foreign investment, particularly for vacation homes and short-term rentals. Property prices are projected to rise 5-10% in 2025, moderated by adjustments to the Golden Visa program's €800,000 threshold for high-demand areas since August 2024, yet sustained by ongoing interest in coastal villas and apartments.[109] Foreign direct investment in Greek real estate hit a record 54.2% of total FDI in 2024, with Chalkidiki's market buoyed by tourism-driven appreciation and a surge in transactions near Thessaloniki.[110] This influx has spurred secondary market growth at 6% annually, though overbuilding concerns in late 2025 highlight risks of supply exceeding stabilized demand.[111] The service sector, encompassing hospitality, dining, and ancillary tourism operations, mirrors national patterns where services account for over 80% of economic activity, but in Chalkidiki, it is overwhelmingly tourism-dependent, generating seasonal jobs in hotels and eateries while limiting year-round stability. Challenges include labor gaps and infrastructure strain from visitor influxes, yet the region's economic resilience is evident in late-2025 assessments of positive turnover amid pre-booking surges exceeding 100% for some accommodations.[112] Overall, these sectors interlink causally, with tourism inflows directly bolstering real estate values and service employment, though vulnerability to external shocks like geopolitical tensions persists.Environmental controversies

Gold mining disputes and ecological claims

The Skouries mining project, located in the Aristotelis municipality of Chalkidiki, involves the extraction of gold and copper from a porphyry deposit estimated to contain approximately 4.2 million ounces of recoverable gold equivalent. Operated by Eldorado Gold through its subsidiary Hellas Gold, the project received initial environmental permits from the Greek Ministry of Environment in 2011, prompting widespread local opposition over potential ecological harm. Critics, including environmental groups and residents, have argued that the open-pit mining would lead to significant deforestation, with the revised environmental impact assessment expanding the affected land area to over 1,788 acres, including ancient forests in a protected Natura 2000 site.[113][114][92] Ecological concerns center on risks to water resources and biodiversity, with opponents citing potential contamination from tailings and processing waste, including heavy metals like arsenic and sulfur compounds released during pressure oxidation of sulfide ores. Existing operations at nearby Eldorado sites, such as Olympias, have been linked to documented effluent pollution affecting local streams, raising fears of similar outcomes at Skouries despite the company's adoption of filtered dry-stack tailings to reduce water usage by up to 40% and minimize seepage. Independent analyses have questioned the adequacy of the environmental impact assessments, alleging underestimation of hydrological impacts on the Strymon River basin and threats to endemic species in the region's wetlands and forests. Eldorado maintains that comprehensive monitoring systems, including real-time sensors for air, water, and soil quality, ensure compliance with EU standards, and that the project avoids cyanide heap leaching in favor of enclosed flotation and autoclave processes.[115][116][117][98] Disputes escalated in 2012 with mass protests in Ierissos and surrounding villages, where up to 3,000 demonstrators rallied against the project, leading to clashes with police and allegations of excessive force, including beatings and arbitrary arrests. A notable incident occurred on February 17, 2013, when arson damaged equipment at the site, resulting in trials of 21 local activists charged with terrorism-related offenses, though convictions were later appealed amid claims of political persecution. The SYRIZA government, upon taking power in 2015, suspended permits citing environmental flaws, prompting Eldorado to win international arbitration awards totaling over €100 million against Greece for delays, but construction resumed after a revised plan was approved in 2021 under the New Democracy administration.[118][119][120] As of December 31, 2025, Phase 2 construction at Skouries is 78% complete, with first copper-gold concentrate production expected towards the end of Q1 2026 and commercial production in mid-2026, potentially boosting Eldorado's annual production to 665,000 ounces by 2027. Proponents highlight economic benefits, including 2,000 construction jobs and long-term royalties to the Greek state exceeding €1 billion, arguing that modern safeguards outweigh risks in a region historically mined since antiquity. Skeptics, however, contend that short-term gains cannot justify irreversible biodiversity loss, with ongoing legal challenges in Greek courts questioning permit validity based on EU environmental directives.[121][122][123][97]Overdevelopment from tourism and infrastructure

The expansion of tourism infrastructure in Chalkidiki, including hotels, resorts, and related facilities, has accelerated since the early 2000s, contributing to economic growth but raising alarms over saturation. In 2024, tourism demand in the region increased by 10.5% from key markets compared to the previous year, sustaining high occupancy rates amid a broader national hotel capacity buildup. However, a September 2025 survey of local business owners revealed that 72% considered construction activity excessive, with 70% warning of risks to the area's appeal from overbuilding.[124][111] This development has intensified pressure on natural resources, particularly water supplies, amid seasonal influxes of millions of visitors. Summer 2025 saw widespread water shortages and intermittent outages across Chalkidiki's municipalities, attributed to overwhelmed reservoirs strained by tourism demands, agricultural use, and prolonged droughts with minimal rainfall over prior winters. Power blackouts became routine, alongside failures in sewage treatment networks, as infrastructure lagged behind visitor volumes exceeding local capacity.[125][126] Local authorities have responded with emergency measures, such as commissioning water distribution studies in Kassandra municipality in July 2025, while calling for a comprehensive regional "master plan" to address long-term sufficiency. Allegations of corruption in urban planning have compounded issues, with a December 2024 probe uncovering bribes for illegal building permits in Sithonia, including unauthorized expansions that bypass environmental safeguards. These practices have fueled resident complaints about habitat fragmentation and visual degradation of coastal landscapes, though quantitative data on deforestation or biodiversity loss specific to tourism remains limited.[127][128][129] Despite economic benefits—such as revenue gains of up to 37% for some hospitality operators in 2024—sustained overdevelopment threatens ecological balance and infrastructure resilience, prompting debates on zoning reforms to cap expansions in vulnerable zones.[104]Demographics

Population statistics and trends

The Chalkidiki regional unit recorded a population of 102,084 in the 2021 Population-Housing Census conducted by the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT). This figure excludes the autonomous monastic community of Mount Athos, which maintains a separate population of approximately 2,000 residents, primarily monks. The regional unit spans 2,924 square kilometers, resulting in a population density of 34.91 inhabitants per square kilometer. From 2011 to 2021, Chalkidiki's population declined at an average annual rate of 0.35%, reflecting broader demographic pressures in Greece such as low birth rates, emigration during the economic crisis, and an aging population. This marked a reversal from earlier growth, driven by internal migration toward coastal areas for tourism-related opportunities, though net losses have persisted amid national trends of population contraction.[130] Preliminary estimates for 2024 indicate a further slight decrease to around 101,736 residents.[131]Ethnic composition and migration patterns

The population of Chalkidiki regional unit is predominantly ethnic Greek, reflecting the broader homogeneity of Greece where ethnic Greeks form over 93% of the national total. In the 2021 census data for the unit, approximately 89,805 residents were classified under Greek origin by place of birth or nationality, out of a total population of around 100,000, indicating a strong continuity of indigenous Greek settlement dating back to antiquity and reinforced through historical assimilations.[132] Small indigenous minorities, such as Vlachs or residual Slavic-speaking groups from Ottoman-era migrations in the Macedonian region, have largely integrated linguistically and culturally into the Greek majority over centuries, with no significant self-identified non-Greek ethnic enclaves documented in recent empirical surveys.[133] Following the 1923 Greco-Turkish population exchange, thousands of ethnic Greek refugees from Anatolia and East Thrace were resettled in Chalkidiki, significantly augmenting the local Greek population and contributing to demographic stability amid post-war recoveries. This influx, estimated in the tens of thousands regionally, integrated rapidly and shaped village-level communities, particularly in coastal and inland areas.[134] Modern ethnic diversity stems primarily from post-1990s economic immigration, with non-Greek residents numbering about 12,000 in the unit, including 1,355 from EU countries, 10,063 from other European nations (predominantly Balkan states like Albania and Bulgaria), and 712 from Asia, often comprising temporary or low-skilled workers. Migration patterns in Chalkidiki feature net inflows driven by economic opportunities in tourism and agriculture, contrasting with Greece's national emigration trends during the 2010s debt crisis. Seasonal labor migration from neighboring Balkan countries has increased since the 1990s, with immigrants filling roles in hospitality and farming, leading to higher migrant proportions in rural and remote municipalities compared to urban centers like Polygyros.[135] Nationally, 2023 data show positive net migration of 16,355 persons, supporting modest population growth in peripheral regions like Chalkidiki, where the 2021 census recorded an addition of over 1,700 residents amid tourism-driven settlement. Internal Greek migration from mainland areas has also contributed, though outflows of younger demographics to Thessaloniki persist due to limited year-round employment.[136][137]Culture and society

Mount Athos religious traditions

Mount Athos, an autonomous monastic republic on the easternmost prong of the Chalkidiki peninsula, preserves ancient Eastern Orthodox traditions centered on asceticism and unceasing prayer. The community comprises 20 sovereign monasteries, established progressively from the 10th century onward, housing approximately 2,000 monks from diverse Orthodox nations who dedicate their lives to spiritual discipline, communal worship, and manual labor in accordance with the typikon, or rule, derived from Byzantine precedents.[4][138] These institutions operate primarily under the cenobitic system, where monks share property communally under an elected abbot, emphasizing obedience, poverty, and chastity, though affiliated sketes—clusters of hermitages—may follow idiorrhythmic practices allowing greater personal autonomy in ascetic pursuits while maintaining shared liturgical and economic structures.[139][140] Central to Athonite spirituality is hesychasm, a contemplative tradition revived in the 14th century by figures like Gregory Palamas, which seeks inner stillness (hesychia) through repetitive invocation of the Jesus Prayer—"Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner"—combined with controlled breathing and physical posture to achieve direct experience of divine light. This practice, rooted in earlier desert monasticism but formalized on Athos amid theological controversies resolved at councils in 1341, 1347, and 1351, distinguishes Athonite life by prioritizing solitude, vigilance against passions, and theosis, or deification, over external works alone. Monks engage in continuous prayer cycles, including the Divine Office with up to eight daily services, extending to 15 hours uninterrupted on major feasts, alongside scriptural study and icon veneration that reinforce doctrinal purity against historical challenges like iconoclasm.[141][142] A defining tradition is the avaton, a canonical prohibition barring women from the peninsula, codified in Byzantine imperial chrysobulls from 1045 and reaffirmed in Mount Athos's 1926 constitutional charter under Greek sovereignty, extending even to female animals except cats for pest control. Attributed to a legendary apparition of the Virgin Mary claiming Athos as her garden, the rule enforces spiritual focus by eliminating distractions, with violations historically punishable by excommunication or expulsion, though modern enforcement relies on self-policing and limited pilgrim access via diamonitirion permits. Daily monastic routines integrate this isolation with rigorous fasting—abstaining from meat, dairy, and oil on approximately 200 days annually, per Orthodox kalends—vegetarian meals limited to one or two per day after vespers, and labor in pursuits like beekeeping, viticulture, and manuscript preservation to sustain self-sufficiency and humility.[143][144][145]Notable inhabitants and local customs

Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher known as the Stagirite, was born in 384 BC in Stagira, an ancient city located in the northern part of Chalkidiki near modern Stavros.[146] His father Nicomachus served as physician to King Amyntas of Macedon, influencing Aristotle's early exposure to empirical observation and biology. Stagira's ruins, excavated since the 19th century, include fortifications and remnants attesting to its role as a Chalcidian colony founded around the 7th century BC.[147] Local customs in Chalkidiki preserve Byzantine and Ottoman-era traditions, often tied to Orthodox Christian feasts and agrarian cycles. New Year's Eve features the vassilopita, a coin-embedded pie or bread varying by village—such as rice pie in Nikiti or tsigiropita in Galatista—symbolizing prosperity when the coin is found.[148] In Polygyros, youths dressed as shepherds perform door-to-door carols on the same eve, echoing pastoral heritage.[148] Easter observances highlight communal rituals, including the burning of a Judas effigy at midnight on Holy Saturday in villages like Gomati, Hanioti, and Neos Marmaras to symbolize purification.[148] Arnea hosts multi-day events: traditional costumes and red-dyed eggs on the first day, a kantari weighing contest with prizes on the second, and the koutsamos procession with uniformed men, horses, and egg-shooting at Prophet Elias church on the third.[148] Sykia features horse racing on Easter's third day following a beachside liturgy, blending faith and equestrian skill.[148] Summer customs include klidona on the eve of the feast of Ai-Giannis (June 24), where unmarried women divine future spouses using "silent water" and personal items thrown into a fire, accompanied by purification leaps over bonfires in village squares.[148] Historical commemorations, such as Of Khar’ kou t’ aloni feasts in Palaiochori and Ierissos, revive events from the region's Ottoman resistance, featuring ceremonies and local cuisine.[148] These practices, rooted in pre-industrial village life, persist amid tourism, maintaining ties to Chalkidiki's rural identity through music on instruments like the laouto and dishes such as souvlaki.[149]Media and cultural institutions

Local media in Chalkidiki serve the region's residents and seasonal tourists, focusing on news, tourism updates, and local events, often overlapping with broader Central Macedonia coverage from Thessaloniki. Key radio stations include Radio Halkidiki 98.8 FM, which broadcasts pop music and local programming from the peninsula,[150] and Laikos Xalkidikis 97.3 FM, specializing in folk genres.[151] Additional outlets such as Kosmoradio Chalkidikis 95.1 FM and Radio Star operate from Nea Moudania, providing music and talk formats.[152] Television channels like TV Chalkidiki, based in Nea Moudania, deliver regional news and entertainment via terrestrial broadcasts.[153] Local newspapers, including Chalkidiki Kathimerini Efimerida, cover daily developments such as tourism and environmental issues, with print and online editions.[154] Typos Chalkidikis also reports on cultural and political matters.[155] Cultural institutions in Chalkidiki emphasize the area's archaeological, Byzantine, and ethnographic heritage, with museums concentrated in central and eastern municipalities. The Anthropological Museum of Petralona displays prehistoric artifacts and fossils from the nearby cave system, highlighting early human presence in the region.[156] The Archaeological Museum of Polygyros houses exhibits from ancient Olynthos and other sites, including pottery and inscriptions from the Classical period.[157] Folklore museums preserve rural traditions: the Folklore Museum of Arnea features weaving tools and household items from Ottoman-era villages,[158] while the Folklore Museum of Athitos showcases agricultural implements and costumes.[158] The Fisheries Museum in Nea Gonia documents maritime history with boat models and tools.[158] Theaters are modest and seasonal, often open-air venues hosting summer performances; the Garden Theater in Kassandra accommodates cultural events and concerts amid gardens.[159] Cultural centers, such as the Cultural Center of Ierissos, promote Athonian influences through exhibitions and events on monastic art and local crafts.[160] Libraries and community halls in Polygyros and Arnea support reading programs and folk events, though they remain smaller-scale compared to national institutions.[161] These facilities collectively safeguard Chalkidiki's diverse historical layers, from prehistoric settlements to Byzantine legacies, amid tourism pressures.Infrastructure

Transportation systems

Chalkidiki lacks its own international airport, with most visitors accessing the region via Thessaloniki Airport (SKG), approximately 70-100 km from key destinations depending on the location. From the airport, options include KTEL buses to the Thessaloniki KTEL Chalkidikis station followed by onward regional buses, rental cars, or private transfers, with bus journeys to central Chalkidiki areas taking 1-3 hours.[162] [163] The primary road network consists of national highways and provincial roads connecting Thessaloniki to Chalkidiki's three peninsulas (Kassandra, Sithonia, and Athos), with the main route being the Thessaloniki-Nea Moudania highway (EO62). Local roads link villages, beaches, and Mount Athos, though narrower paths in remote areas like Sithonia can be winding and seasonal. Public bus services, operated by KTEL Chalkidikis, provide intercity and intraregional connectivity, departing frequently from Thessaloniki's KTEL station to hubs like Nea Moudania, Polygyros, and Neos Marmaras, with daily routes to most villages and beaches. Fares are economical, starting around €5-€15 one-way, and schedules run year-round but intensify in summer.[164] [165] [166] Maritime transport is limited to small ports serving local needs and restricted access. Key facilities include Tripiti port for ferries to Ammouliani island (20-minute crossings, multiple daily in season), and Ouranoupoli and Ierissos for caiques to Mount Athos monasteries (diamonitirion permits required for non-Orthodox males). No major inter-island or international ferry lines operate directly from Chalkidiki; larger ports in Thessaloniki or Kavala handle broader Aegean connections. Taxis and ride-sharing supplement buses, but car rentals dominate for flexibility given sparse intrapeninsular public options.[167] [168]Energy developments and utilities

Chalkidiki's electricity supply is managed through Greece's national grid, primarily operated by the Public Power Corporation (PPC), with distribution handled by the Independent Power Transmission Operator (ADMIE). The region experiences periodic power outages, particularly during peak summer tourism seasons, due to high demand overwhelming infrastructure, as reported in August 2025 when blackouts affected both locals and visitors amid water shortages and network strain.[125][126] Recent energy developments emphasize renewable integration and storage to address intermittency and grid stability. The Themelio Battery Energy Storage System (BESS), a 49 MW/127 MWh facility near Polygyros, began construction in April 2025 and achieved completion by October 2025, with full commercial operations slated for December 2025; developed by Principia, it represents one of Greece's earliest large-scale BESS projects under a Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme to support renewable curtailment mitigation.[169][170][171] Wind power is advancing with the 56 MW Chalkidiki wind farm, commissioned by developer Alterric using nine Nordex N175/6.X turbines—the first such deployment in Greece—following a turbine order in December 2024 for installation in the regional unit. Solar photovoltaic projects include the Polygyros solar farm under construction and a broader Chalkidiki solar farm in pre-construction as of May 2025, contributing to Greece's regional push toward 1.8 GW licensed PV capacity in Macedonia and Central Greece.[172][173][174][175] On Mount Athos, an autonomous monastic republic within Chalkidiki, the Vatopedi Monastery installed Greece's largest grid-forming BESS at 3 MW in July 2025, entering trial operations to enhance energy independence amid the area's isolation from the mainland grid. These initiatives align with national targets for renewables to exceed 61% of electricity consumption by 2030, though local implementation faces challenges from terrain and tourism pressures.[176]References

- https://en.climate-data.org/europe/[greece](/page/Greece)/chalkidiki-10374/