Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Coccidioides

View on Wikipedia

| Coccidioides | |

|---|---|

| |

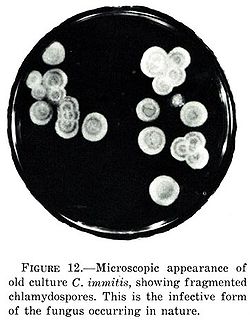

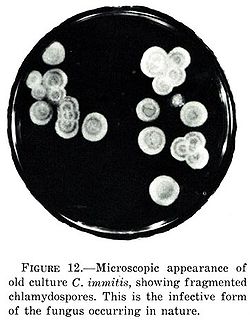

| Coccidioides immitis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Onygenales |

| Family: | Onygenaceae |

| Genus: | Coccidioides G.W.Stiles (1896)[1] |

| Type species | |

| Coccidioides immitis G.W.Stiles (1896)

| |

| Species | |

|

C. esteriformis | |

Coccidioides is a genus of dimorphic ascomycetes in the family Onygenaceae. Member species are the cause of coccidioidomycosis, also known as San Joaquin Valley fever, an infectious fungal disease largely confined to the Western Hemisphere and endemic in the Southwestern United States.[2] The host acquires the disease by respiratory inhalation of spores disseminated in their natural habitat. The causative agents of coccidioidomycosis are Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. Both C. immitis and C. posadasii are indistinguishable during laboratory testing and commonly referred in literature as Coccidioides.[3]

Clinical presentation

[edit]

Coccidioidomycosis is amazingly diverse in terms of its scope of clinical presentation, as well as clinical severity. About 60% of Coccidioides infections as determined by serologic conversion are asymptomatic. The most common clinical syndrome in the other 40% of infected patients is an acute respiratory illness characterized by fever, cough, and pleuritic pain. Skin manifestations, such as erythema nodosum, are also common with Coccidioides infection. Coccidioides infection can cause a severe and difficult-to-treat meningitis in AIDS and other immunocompromised patients, and occasionally in immunocompetent hosts. Infection can sometimes cause acute respiratory distress syndrome and fatal multilobar pneumonia. The risk of symptomatic infection increases with age.

Epidemiology

[edit]The primary coccidioidomycosis-endemic areas are located in Southern California and southern Arizona, and northern Mexico, in Sonora, Nuevo León, Coahuila, and Baja California, where it resides in soil.[4] Both C. immitis and C. posadasii were viewed as desert saprophytes, but recent genomic research revealed Coccidioides species to have evolved interacting with their animal hosts.[5]

Etymology

[edit]The soil fungus Coccidioides was discovered in 1892 by Alejandro Posadas, a medical student, in an Argentinian soldier with widespread disease. Biopsy specimens revealed organisms that resembled the protozoan Coccidia (from the Greek kokkis, "little berry"). In 1896, Gilchrist and Rixford named the organism Coccidioides ("resembling Coccidia") immitis (Latin for “harsh,” describing the clinical course). Ophüls and Moffitt proved that C. immitis was a fungus rather than a protozoan in 1900. In 2002, C. immitis was divided into a second species, C. posadasii, after Alejandro Posadas.[6]

References

[edit]This article cites public domain text from the CDC, as shown.

- ^ Rixford E, Gilchrist TC (1896). "Two cases of protozoan (coccidioidal) infection of the skin and other organs". Johns Hopkins Hospital Reports. 1: 209–268 (see p. 243).

- ^ "Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ^ Fauci, Anthony S. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2008.

- ^ Baptista-Rosas, Riquelme M., Hinojosa A. Ecological niche modeling of Coccidioides spp. in Western North American deserts. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2007, Vol. 1111, pp. 35–46.

- ^ Sharpton, T. J.; Stajich, J. E.; Rounsley, S. D.; et al. (October 2009). "Comparative Genomic Analyses of the Human Fungal Pathogens Coccidioides and Their Relatives". Genome Research. 19 (10): 1722–31. doi:10.1101/gr.087551.108. PMC 2765278. PMID 19717792. Archived from the original on 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ Anonymous (June 2015). "Etymologia: Coccidioides". Emerg Infect Dis. 21 (6): 1031. doi:10.3201/eid2106.ET2106. PMC 4451898.