Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Commutative diagram

View on Wikipedia

In mathematics, and especially in category theory, a commutative diagram is a diagram such that all directed paths in the diagram with the same start and endpoints lead to the same result.[1] It is said that commutative diagrams play the role in category theory that equations play in algebra.[2]

Description

[edit]A commutative diagram often consists of three parts:

Arrow symbols

[edit]In algebra texts, the type of morphism can be denoted with different arrow usages:

- A monomorphism may be labeled with a [3] or a .[4]

- An epimorphism may be labeled with a .

- An isomorphism may be labeled with a .

- The dashed arrow typically represents the claim that the indicated morphism exists (whenever the rest of the diagram holds); the arrow may be optionally labeled as .

- If the morphism is in addition unique, then the dashed arrow may be labeled or .

- If the morphism acts between two arrows (such as in the case of higher category theory), it's called preferably a natural transformation and may be labelled as (as seen below in this article).

The meanings of different arrows are not entirely standardized: the arrows used for monomorphisms, epimorphisms, and isomorphisms are also used for injections, surjections, and bijections, as well as the cofibrations, fibrations, and weak equivalences in a model category.

Verifying commutativity

[edit]Commutativity makes sense for a polygon of any finite number of sides (including just 1 or 2), and a diagram is commutative if every polygonal subdiagram is commutative.

Note that a diagram may be non-commutative, i.e., the composition of different paths in the diagram may not give the same result.

Examples

[edit]Example 1

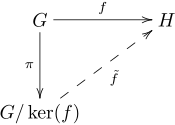

[edit]In the left diagram, which expresses the first isomorphism theorem, commutativity of the triangle means that . In the right diagram, commutativity of the square means .

|

|

Example 2

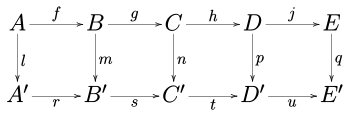

[edit]In order for the diagram below to commute, three equalities must be satisfied:

Here, since the first equality follows from the last two, it suffices to show that (2) and (3) are true in order for the diagram to commute. However, since equality (3) generally does not follow from the other two, it is generally not enough to have only equalities (1) and (2) if one were to show that the diagram commutes.

|

Diagram chasing

[edit]Diagram chasing (also called diagrammatic search) is a method of mathematical proof used especially in homological algebra, where one establishes a property of some morphism by tracing the elements of a commutative diagram. A proof by diagram chasing typically involves the formal use of the properties of the diagram, such as injective or surjective maps, or exact sequences.[5] A syllogism is constructed, for which the graphical display of the diagram is just a visual aid. It follows that one ends up "chasing" elements around the diagram, until the desired element or result is constructed or verified.

Examples of proofs by diagram chasing include those typically given for the five lemma, the snake lemma, the zig-zag lemma, and the nine lemma.

In higher category theory

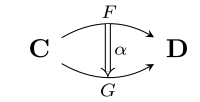

[edit]In higher category theory, one considers not only objects and arrows, but arrows between the arrows, arrows between arrows between arrows, and so on ad infinitum. For example, the category of small categories Cat is naturally a 2-category, with functors as its arrows and natural transformations as the arrows between functors. In this setting, commutative diagrams may include these higher arrows as well, which are often depicted in the following style: . For example, the following (somewhat trivial) diagram depicts two categories C and D, together with two functors F, G : C → D and a natural transformation α : F ⇒ G:

There are two kinds of composition in a 2-category (called vertical composition and horizontal composition), and they may also be depicted via pasting diagrams (see 2-category#Definitions for examples).

Diagrams as functors

[edit]A commutative diagram in a category C can be interpreted as a functor from an index category J to C; one calls the functor a diagram.

More formally, a commutative diagram is a visualization of a diagram indexed by a poset category. Such a diagram typically includes:

- a node for every object in the index category,

- an arrow for a generating set of morphisms (omitting identity maps and morphisms that can be expressed as compositions),

- the commutativity of the diagram (the equality of different compositions of maps between two objects), corresponding to the uniqueness of a map between two objects in a poset category.

Conversely, given a commutative diagram, it defines a poset category, where:

- the objects are the nodes,

- there is a morphism between any two objects if and only if there is a (directed) path between the nodes,

- with the relation that this morphism is unique (any composition of maps is defined by its domain and target: this is the commutativity axiom).

However, not every diagram commutes (the notion of diagram strictly generalizes commutative diagram). As a simple example, the diagram of a single object with an endomorphism (), or with two parallel arrows (, that is, , sometimes called the free quiver), as used in the definition of equalizer need not commute. Further, diagrams may be messy or impossible to draw, when the number of objects or morphisms is large (or even infinite).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Commutative Diagram". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- ^ Mazzola, Guerino; Milmeister, Gérard; Weissmann, Jody (2005). Comprehensive Mathematics for Computer Scientists 2. Springer. p. 140. doi:10.1007/b138337. ISBN 978-3-540-26937-3.

- ^ "Maths - Category Theory - Arrow - Martin Baker". www.euclideanspace.com. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- ^ Riehl, Emily (2016-11-17). "1". Category Theory in Context (PDF). Dover Publications. p. 11.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Diagram Chasing". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adámek, Jiří; Horst Herrlich; George E. Strecker (1990). Abstract and Concrete Categories (PDF). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60922-6. Now available as free on-line edition (4.2MB PDF).

- Barr, Michael; Wells, Charles (2002). Toposes, Triples and Theories (PDF). Springer. ISBN 0-387-96115-1. Revised and corrected free online version of Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften (278) Springer-Verlag, 1983).

External links

[edit]- Diagram Chasing at MathWorld

- WildCats is a category theory package for Mathematica. Manipulation and visualization of objects, morphisms, categories, functors, natural transformations.

Commutative diagram

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In category theory, a commutative diagram is a visual representation of objects and morphisms within a category such that the composition of morphisms along any two distinct paths connecting the same pair of objects yields the same resulting morphism. This ensures that the diagram encodes equalities of composite morphisms independently of the chosen path, providing a concise way to express structural relationships without explicit computation of each composition.[8] Such diagrams typically depict objects as vertices and morphisms as directed arrows between them. Commutativity implies path independence: for any two paths from an object to an object , the composite morphisms must be identical in the category. This property captures the essence of relational equalities in categorical structures, where the diagram serves as a shorthand for verifying that multiple ways of mapping between objects are consistent.[9] Formally, a commutative diagram is defined via a functor , where is a small index category (often a finite graph viewed as a free category) and is the ambient category. The diagram commutes if, for every pair of parallel arrows (morphisms with the same domain and codomain) in , their images under are equal in ; more generally, all composite morphisms along parallel paths in map to equal composites in . Equivalently, in the elementary sense, if consists of vertices and edges , then assigns objects of to vertices and morphisms of to edges (preserving sources and targets), and the diagram is commutative precisely when the composite for any two paths in from a vertex to a vertex .[9] The concept of commutative diagrams was popularized in the category theory literature of the 1940s and 1950s through the foundational works of Saunders Mac Lane and Samuel Eilenberg, with early documented uses appearing in the 1945 paper by Samuel Eilenberg and Saunders Mac Lane titled "A General Theory of Natural Equivalences," and further developed in Mac Lane's 1963 monograph "Homology".[10]Notation and Symbols

In commutative diagrams, morphisms between objects are typically represented by solid arrows, such as or , with labels indicating the specific map, for example, .[11] Dashed arrows, denoted by or similar, are conventionally used to indicate implied, hypothetical, or uniquely determined morphisms, often in the context of universal properties where existence is asserted but not explicitly constructed.[12] These arrows ensure visual distinction between given structure and derived elements, promoting clarity in diagram interpretation.[13] Common diagram shapes include squares, which depict two parallel pairs of morphisms whose compositions must equalize; triangles, representing triangular identities or cone structures; and polygons, such as pentagons or hexagons, for more intricate relations involving multiple paths.[11] These geometric configurations are arranged to visually encode the requirement that all paths between two objects yield the same composite morphism, with objects positioned at vertices and arrows along edges.[11] For rendering these diagrams, LaTeX-based tools like TikZ with its tikz-cd extension provide precise control over arrow styles, labels, and layouts, generating high-quality output suitable for mathematical publications.[12] Similarly, the xy-pic package specializes in category-theoretic diagrams, supporting complex arrow decorations and positional logic for automated alignment.[14] Graphviz offers an alternative for automated rendering of directed graphs, including commutative structures, through its DOT language, which excels in handling larger or algorithmic diagram generation.[15] A notable variation in notation involves double arrows, such as , to denote natural transformations between functors, briefly introducing a layer above ordinary morphisms without delving into higher categorical details.[11]Commutativity Verification

To verify the commutativity of a diagram in a category, one follows a systematic process that begins with identifying all directed paths between any pair of objects in the diagram. For each such pair, the composite morphisms along these paths must be computed and shown to be equal; for instance, in a triangular diagram with morphisms , , and , commutativity requires . This path-by-path equality check ensures that the diagram factors through a preorder where parallel paths are identified, as formalized in the elementary definition of a commutative diagram.[9] Algebraic verification often leverages properties inherent to categorical structures, such as functoriality, to establish equalities without explicit path computations. Functors preserve the commutativity of diagrams by mapping objects and morphisms while maintaining composition and identities, so if a diagram commutes in the source category, its image under a functor commutes in the target category; this is particularly useful for naturality squares of natural transformations, where commutativity follows directly from the definition. Associativity of composition further aids in rearranging paths to match known equalities, reducing the need for direct calculation in larger diagrams.[16] Common pitfalls in verification arise when the underlying structure lacks full categorical properties, such as in mere sets without specified composition, where paths may not yield well-defined composites, leading to non-commutativity unless additional relations are imposed. In diagrams with cycles, overlooking the requirement for identity morphisms along loops can cause inconsistencies, as compositions must return to the starting object unchanged. Similarly, fork structures (e.g., two morphisms from a common source) demand outright equality of the morphisms, not merely post-composition with a common target, to avoid subtle failures in preorder factorization. Detecting such issues involves checking for unresolved parallel paths or violations of preorder conditions.[9] For practical verification, especially in finite or concrete categories, matrix representations provide a computational approach: in finite-dimensional vector spaces, morphisms are represented as matrices, and commutativity reduces to equality of matrix products along paths, verifiable via linear algebra software. In formal settings, proof assistants like Coq enable rigorous checks through libraries that automate diagram chasing and commutativity proofs; for example, a Coq-based system uses tactics to synthesize and verify equalities in 1-categories by embedding diagrams as quivers and resolving the "commerge" problem for acyclic cases. These tools ensure decidability and reliability for complex verifications.[17]Examples

Basic Algebraic Examples

One foundational example of a commutative diagram arises in the context of group homomorphisms, particularly through short exact sequences. Consider the sequence , where is a normal subgroup of the group , is the inclusion map, is the canonical projection, and the maps are group homomorphisms. This diagram is commutative because the composition is the zero map, and exactness ensures with surjective.[18][19] In ring theory, a commutative square demonstrates the universal property of quotient rings. The canonical projection and the inclusion form two paths from ; for any ring homomorphism such that annihilates the image (as in the case where has characteristic dividing ), there exists a unique induced map making the square and commute, i.e., . While no nontrivial map exists for due to characteristic differences, the diagram illustrates the factoring property when applicable to other targets like finite fields.[20][21] For vector spaces, commutative diagrams often appear in the representation of linear maps under change of bases. Suppose and are finite-dimensional vector spaces over a field , with bases for and for , and a linear map . A change of basis in via invertible matrix yields a new basis, transforming to in the new coordinates, where is the change-of-basis matrix for . The square diagram , commutes, as the representations align under basis transformations preserving linearity.[22] A specific commutative triangle exemplifies the first isomorphism theorem for groups. For a group homomorphism with kernel , the diagram consists of the inclusion , the projection , and the induced isomorphism , such that and the triangle with commutes, establishing .[23]Topological and Geometric Examples

In topology, commutative diagrams arise naturally in the study of covering spaces and their relation to the fundamental group. Consider a covering space of a path-connected, locally path-connected space , with a subgroup corresponding to the covering via the Galois correspondence. The inclusion induces a commutative diagram where the projection commutes with the inclusion, reflecting how loops in the covering space project to loops in the base fixed by the monodromy action.[24] Deck transformations, which are automorphisms of the covering space commuting with the projection , further illustrate commutativity: for a deck transformation , the diagram and commutes, ensuring that preserves fibers and induces the identity on the base.[25] This structure underpins the isomorphism between the deck transformation group and the quotient , highlighting how topological coverings encode group actions via commuting projections.[24] Homotopy commutative squares extend this to higher-dimensional invariants, particularly in the context of homotopy groups. A homotopy commutative square consists of maps , , , and such that up to homotopy, meaning there exists a homotopy with and . In the definition of higher homotopy groups , such squares appear in the relative homotopy long exact sequence for a pair , where the boundary map is induced by a homotopy commutative diagram involving the inclusion and quotient , ensuring that spheres in the quotient lift appropriately up to homotopy.[24] For instance, in computing , the square relating the attaching map of cells in the CW-complex structure of the sphere commutes up to homotopy, confirming for the degree.[24] This homotopy commutativity captures the invariance of homotopy classes under continuous deformations, distinguishing topological from strict algebraic commutativity. In geometry, commutative diagrams manifest in pullbacks, such as the fiber product of manifolds. Given smooth maps and between smooth manifolds, the fiber product forms the vertex of a commutative square with projections and , satisfying .[26] If and are submersions, the fiber product inherits a smooth manifold structure, with the diagram's commutativity ensuring it is the categorical pullback in the category of smooth manifolds.[27] This construction is pivotal in fiber bundle theory, where pulling back a bundle along yields via the commutative square involving the bundle projection, preserving local triviality and transition functions.[26] An illustrative example from differential geometry involves connection forms on principal bundles and their curvature. For a principal -bundle with connection 1-form , the curvature 2-form satisfies the structure equation, which underlies commutativity in the diagram for horizontal lifts: the infinitesimal parallel transport along vector fields commutes with the right -action via the relation , ensuring is horizontal and -invariant. In the Maurer-Cartan form context, this commutativity via curvature equations measures the failure of flatness, as seen in the Bianchi identity , where the covariant derivative vanishes, forming a closed loop in the de Rham complex of Lie algebra-valued forms. Such diagrams connect local connection data to global topological invariants like Chern classes.[28]Techniques and Applications

Diagram Chasing

Diagram chasing is a proof technique in homological algebra that involves systematically tracing elements or morphisms through the paths of a commutative diagram to establish equalities, injectivity, surjectivity, or exactness. This method exploits the commutativity of the diagram and properties such as exactness of sequences, kernels, and cokernels to "chase" an element forward along one path and backward along another equivalent path, often revealing relationships between homology groups or modules.[29][30] A prominent example is the snake lemma, which derives a long exact sequence from a commutative diagram of two short exact sequences of abelian groups or modules. Consider the following commutative diagram with exact rows:0 → A ──→ B ──→ C ──→ 0

│ │ │

↓ ↓ ↓

0 → A'──→ B'──→ C'──→ 0

0 → A ──→ B ──→ C ──→ 0

│ │ │

↓ ↓ ↓

0 → A'──→ B'──→ C'──→ 0

A ──→ B ──→ C ──→ D ──→ E

│ │ │ │ │

A'──→ B'──→ C'──→ D'──→ E'

A ──→ B ──→ C ──→ D ──→ E

│ │ │ │ │

A'──→ B'──→ C'──→ D'──→ E'