Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Conformity

View on WikipediaThis article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (May 2025) |

Conformity or conformism is the act of matching attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to group norms, politics or being like-minded.[1] Norms are implicit, specific rules, guidance shared by a group of individuals, that guide their interactions with others. People often choose to conform to society rather than to pursue personal desires – because it is often easier to follow the path others have made already, rather than forging a new one. Thus, conformity is sometimes a product of group communication.[2] This tendency to conform occurs in small groups and/or in society as a whole and may result from subtle unconscious influences (predisposed state of mind), or from direct and overt social pressure. Conformity can occur in the presence of others, or when an individual is alone. For example, people tend to follow social norms when eating or when watching television, even if alone.[3]

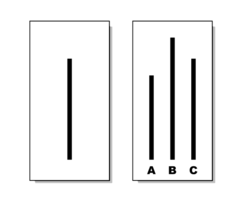

Solomon Asch, a social psychologist whose obedience research remains among the most influential in psychology, demonstrated the power of conformity through his experiment on line judgment. The Asch conformity experiment demonstrates how much influence conformity has on people. In a laboratory experiment, Asch asked 50 male students from Swarthmore College in the US to participate in a 'vision test'. Asch put a naive participant in a room with seven stooges in a line judgment task. When confronted with the line task, each stooge had already decided what response they would give. The real members of the experimental group sat in the last position, while the others were pre-arranged experimenters who gave apparently incorrect answers in unison; Asch recorded the last person's answer to analyze the influence of conformity. Surprisingly, about one third (32%) of the participants who were placed in this situation sided with the clearly incorrect majority on the critical trials. Over the 12 critical trials, about 75% of participants conformed at least once. Ash demonstrated in this experiment that people could produce obviously erroneous responses just to conform to a group of similar erroneous responders, this was called normative influence. After being interviewed, subjects acknowledged that they did not actually agree with the answers given by others. The majority of them, however, believed that groups are wiser or did not want to appear as mavericks and chose to repeat the same obvious misconception. There is another influence that is sometimes more subtle, called informational influence. This is when people turn to others for information to help them make decisions in new or ambiguous situations. Most of the time, people were simply conforming to social group norms that they were unaware of, whether consciously or unconsciously, especially through a mechanism called the Chameleon effect. This effect is when people unintentionally and automatically mimic others' gestures, posture, and speech style in order to produce rapport and create social interactions that run smoothly (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999[4]). It is clear from this that conformity has a powerful effect on human perception and behavior, even to the extent that it can be faked against a person's basic belief system.[5]

Changing one's behaviors to match the responses of others, which is conformity, can be conscious or not.[6] People have an intrinsic tendency to unconsciously imitate other's behaviors such as gesture, language, talking speed, and other actions of the people they interact with.[7] There are two other main reasons for conformity: informational influence and normative influence.[7] People display conformity in response to informational influence when they believe the group is better informed, or in response to normative influence when they are afraid of rejection.[8] When the advocated norm could be correct, the informational influence is more important than the normative influence, while otherwise the normative influence dominates.[9]

People often conform from a desire for security within a group, also known as normative influence[10]—typically a group of a similar age, culture, religion or educational status. This is often referred to as groupthink: a pattern of thought characterized by self-deception, forced manufacture of consent, and conformity to group values and ethics, which ignores realistic appraisal of other courses of action. Unwillingness to conform carries the risk of social rejection. Conformity is often associated in media with adolescence and youth culture, but strongly affects humans of all ages.[11]

Although peer pressure may manifest negatively, conformity can be regarded as either good or bad. Driving on the conventionally-approved side of the road may be seen as beneficial conformity.[12] With the appropriate environmental influence, conforming, in early childhood years, allows one to learn and thus, adopt the appropriate behaviors necessary to interact and develop "correctly" within one's society.[13] Conformity influences the formation and maintenance of social norms, and helps societies function smoothly and predictably via the self-elimination of behaviors seen as contrary to unwritten rules.[14] Conformity was found to impair group performance in a variable environment, but was not found to have a significant effect on performance in a stable environment.[15]

According to Herbert Kelman, there are three types of conformity: 1) compliance (which is public conformity, and it is motivated by the need for approval or the fear of disapproval; 2) identification (which is a deeper type of conformism than compliance); 3) internalization (which is to conform both publicly and privately).[16]

Major factors that influence the degree of conformity include culture, gender, age, size of the group, situational factors, and different stimuli. In some cases, minority influence, a special case of informational influence, can resist the pressure to conform and influence the majority to accept the minority's belief or behaviors.[8]

Definition and context

[edit]Definition

[edit]Conformity is the tendency to change our perceptions, opinions, or behaviors in ways that are consistent with group norms.[17] Norms are implicit, specific rules shared by a group of individuals on how they should behave.[18] People may be susceptible to conform to group norms because they want to gain acceptance from their group.[18]

Peer

[edit]Some adolescents gain acceptance and recognition from their peers by conformity. This peer moderated conformity increases from the transition of childhood to adolescence.[19] It follows a U-shaped age pattern wherein conformity increases through childhood, peaking at sixth and ninth grades and then declines.[20] Adolescents often follow the logic that "if everyone else is doing it, then it must be good and right".[21] However, it is found that they are more likely to conform if peer pressure involves neutral activities such as those in sports, entertainment, and prosocial behaviors rather than anti-social behaviors.[20] Researchers have found that peer conformity is strongest for individuals who reported strong identification with their friends or groups, making them more likely to adopt beliefs and behaviors accepted in such circles.[22][23]

There is also the factor that the mere presence of a person can influence whether one is conforming or not. Norman Triplett (1898) was the researcher that initially discovered the impact that mere presence has, especially among peers.[24] In other words, all people can affect society. We are influenced by people doing things beside us, whether this is in a competitive atmosphere or not. People tend to be influenced by those who are their own age especially. Co-actors that are similar to us tend to push us more than those who are not.

Social responses

[edit]According to Donelson Forsyth, after submitting to group pressures, individuals may find themselves facing one of several responses to conformity. These types of responses to conformity vary in their degree of public agreement versus private agreement.

When an individual finds themselves in a position where they publicly agree with the group's decision yet privately disagrees with the group's consensus, they are experiencing compliance or acquiescence. This is also referenced as apparent conformity. This type of conformity recognizes that behavior is not always consistent with our beliefs and attitudes, which mimics Leon Festinger's cognitive dissonance theory. In turn, conversion, otherwise known as private acceptance or "true conformity", involves both publicly and privately agreeing with the group's decision. In the case of private acceptance, the person conforms to the group by changing their beliefs and attitudes. Thus, this represents a true change of opinion to match the majority.[25]

Another type of social response, which does not involve conformity with the majority of the group, is called convergence. In this type of social response, the group member agrees with the group's decision from the outset and thus does not need to shift their opinion on the matter at hand.[26]

In addition, Forsyth shows that nonconformity can also fall into one of two response categories. Firstly, an individual who does not conform to the majority can display independence. Independence, or dissent, can be defined as the unwillingness to bend to group pressures. Thus, this individual stays true to his or her personal standards instead of the swaying toward group standards. Secondly, a nonconformist could be displaying anticonformity or counterconformity which involves the taking of opinions that are opposite to what the group believes. This type of nonconformity can be motivated by a need to rebel against the status quo instead of the need to be accurate in one's opinion.

To conclude, social responses to conformity can be seen to vary along a continuum from conversion to anticonformity. For example, a popular experiment in conformity research, known as the Asch situation or Asch conformity experiments, primarily includes compliance and independence. Also, other responses to conformity can be identified in groups such as juries, sports teams and work teams.[26]

Main experiments

[edit]Sherif's experiment (1935)

[edit]Muzafer Sherif was interested in knowing how many people would change their opinions to bring them in line with the opinion of a group. In his experiment, participants were placed in a dark room and asked to stare at a small dot of light 15 feet away. They were then asked to estimate the amount it moved. The trick was, there was no movement, it was caused by a visual illusion known as the autokinetic effect.[27] The participants stated estimates ranging from 1–10 inches. On the first day, each person perceived different amounts of movement, but from the second to the fourth day, the same estimate was agreed on and others conformed to it.[28] Over time, the personal estimates converged with the other group members' estimates once discussing their judgments aloud. Sherif suggested this was a simulation for how social norms develop in a society, providing a common frame of reference for people. His findings emphasize that people rely on others to interpret ambiguous stimuli and new situations.

Subsequent experiments were based on more realistic situations. In an eyewitness identification task, participants were shown a suspect individually and then in a lineup of other suspects. They were given one second to identify him, making it a difficult task. One group was told that their input was very important and would be used by the legal community. To the other it was simply an experiment. Being more motivated to get the right answer increased the tendency to conform. Those who wanted to be more accurate conformed 51% of the time as opposed to 35% in the other group.[29] Sherif's study provided a framework for subsequent studies of influence such as Solomon Asch's 1955 study.

Asch's experiment (1951)

[edit]

Solomon E. Asch conducted a modification of Sherif's study, assuming that when the situation was very clear, conformity would be drastically reduced. He exposed people in a group to a series of lines, and the participants were asked to match one line with a standard line. All participants except one were accomplices and gave the wrong answer in 12 of the 18 trials.[30]

The results showed a surprisingly high degree of conformity: 74% of the participants conformed on at least one trial. On average people conformed one third of the time.[30] A question is how the group would affect individuals in a situation where the correct answer is less obvious.[31]

After his first test, Asch wanted to investigate whether the size or unanimity of the majority had greater influence on test subjects. "Which aspect of the influence of a majority is more important – the size of the majority or its unanimity? The experiment was modified to examine this question. In one series the size of the opposition was varied from one to 15 persons."[32] The results clearly showed that as more people opposed the subject, the subject became more likely to conform. However, the increasing majority was only influential up to a point: from three or more opponents, there is more than 30% of conformity.[30]

Besides that, this experiment proved that conformity is powerful, but also fragile. It is powerful because just by having actors giving the wrong answer made the participant to also give the wrong answer, even though they knew it was not correct. It is also fragile, however, because in one of the variants for the experiment, one of the actors was supposed to give the correct answer, being an "ally" to the participant. With an ally, the participant was more likely to give the correct answer than he was before the ally. In addition, if the participant was able to write down the answer, instead of saying out loud, he was also more likely to put the correct answer. The reason for that is because he was not afraid of being different from the rest of the group since the answers were hidden.[33]

Milgram's shock experiment (1961)

[edit]This experiment was conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram in order to portray obedience to authority. They measured the willingness of participants (men aged 20 to 50 from a diverse range of occupations with different levels of education) to obey the instructions from an authority figure to supply fake electric shocks that would gradually increase to fatal levels. Regardless of these instructions going against their personal conscience, 65% of the participants shocked all the way to 450 volts, fully obeying the instruction, even if they did so reluctantly. Additionally, all participants shocked to at least 300 volts.[34]

In this experiment, the subjects did not have punishments or rewards if they chose to disobey or obey. All they might receive is disapproval or approval from the experimenter. Since this is the case they had no motives to sway them to perform the immoral orders or not. One of the most important factors of the experiment is the position of the authority figure relative to the subject (the shocker) along with the position of the learner (the one getting shocked). There is a reduction in conformity depending on if the authority figure or learner was in the same room as the subject. When the authority figure was in another room and only phoned to give their orders the obedience rate went down to 20.5%. When the learner was in the same room as the subject the obedience rate dropped to 40%.[35]

Stanford prison experiment (August 15–21, 1971)

[edit]This experiment, led by psychology professor Philip G. Zimbardo, recruited Stanford students using a local newspaper ad, who he checked to be both physically and mentally healthy.[36] Subjects were either assigned the role of a "prisoner" or "guard" at random over an extended period of time, within a pretend prison setting on the Stanford University Campus. The study was set to be over the course of two weeks but it was abruptly cut short because of the behaviors the subjects were exuding. It was terminated due to the "guards" taking on tyrannical and discriminatory characteristics while "prisoners" showed blatant signs of depression and distress.[37]

In essence, this study showed us a lot about conformity and power imbalance. For one, it demonstrates how situations determines the way our behavior is shaped and predominates over our personality, attitudes, and individual morals. Those chosen to be "guards" were not mean-spirited. But, the situation they were put in made them act accordingly to their role. Furthermore, this study elucidates the idea that humans conform to expected roles. Good people (i.e. the guards before the experiment) were transformed into perpetrators of evil. Healthy people (i.e. the prisoners before the experiment) were subject to pathological reactions. These aspects are also traceable to situational forces. This experiment also demonstrated the notion of the banality of evil which explains that evil is not something special or rare, but it is something that exists in all ordinary people.[citation needed]

Varieties

[edit]Harvard psychologist Herbert Kelman identified three major types of conformity.[16]

- Compliance is public conformity, while possibly keeping one's own original beliefs for yourself. Compliance is motivated by the need for approval and the fear of being rejected.

- Identification is conforming to someone who is liked and respected, such as a celebrity or a favorite uncle. This can be motivated by the attractiveness of the source,[16] and this is a deeper type of conformism than compliance.

- Internalization is accepting the belief or behavior and conforming both publicly and privately, if the source is credible. It is the deepest influence on people, and it will affect them for a long time.

Although Kelman's distinction has been influential, research in social psychology has focused primarily on two varieties of conformity. These are informational conformity, or informational social influence, and normative conformity, also called normative social influence. In Kelman's terminology, these correspond to internalization and compliance, respectively. There are naturally more than two or three variables in society influential on human psychology and conformity; the notion of "varieties" of conformity based upon "social influence" is ambiguous and indefinable in this context.

According to Deutsch and Gérard (1955), conformity results from a motivational conflict (between the fear of being socially rejected and the wish to say what we think is correct) that leads to normative influence, and a cognitive conflict (others create doubts in what we think) which leads to informational influence.[38]

Informational influence

[edit]Informational social influence occurs when one turns to the members of one's group to obtain and accept accurate information about reality.[39] A person is most likely to use informational social influence in certain situations: when a situation is ambiguous, people become uncertain about what to do and they are more likely to depend on others for the answer; and during a crisis when immediate action is necessary, in spite of panic. Looking to other people can help ease fears, but unfortunately, they are not always right. The more knowledgeable a person is, the more valuable they are as a resource. Thus, people often turn to experts for help. But once again people must be careful, as experts can make mistakes too. Informational social influence often results in internalization or private acceptance, where a person genuinely believes that the information is right.[28]

Normative influence

[edit]Normative social influence occurs when one conforms to be liked or accepted by the members of the group. This need of social approval and acceptance is part of our state of humans.[28] In addition to this, we know that when people do not conform with their group and therefore are deviants, they are less liked and even punished by the group.[40] Normative influence usually results in public compliance, doing or saying something without believing in it. The experiment of Asch in 1951 is one example of normative influence. Even though John Turner et al. argued that the post experimental interviews showed that the respondents were uncertain about the correct answers in some cases. The answers might have been evident to the experimenters, but the participants did not have the same experience. Subsequent studies pointed out the fact that the participants were not known to each other and therefore did not pose a threat against social rejection. See: Normative influence vs. referent informational influence

In a reinterpretation of the original data from these experiments Hodges and Geyer (2006)[41] found that Asch's subjects were not so conformist after all: The experiments provide powerful evidence for people's tendency to tell the truth even when others do not. They also provide compelling evidence of people's concern for others and their views. By closely examining the situation in which Asch's subjects find themselves they find that the situation places multiple demands on participants: They include truth (i.e., expressing one's own view accurately), trust (i.e., taking seriously the value of others' claims), and social solidarity (i.e., a commitment to integrate the views of self and others without deprecating). In addition to these epistemic values, there are multiple moral claims as well: These include the need for participants to care for the integrity and well-being of other participants, the experimenter, themselves, and the worth of scientific research.

Deutsch & Gérard (1955) designed different situations that variated from Asch' experiment and found that when participants were writing their answer privately, they gave the correct one.[38]

Normative influence, a function of social impact theory, has three components.[42] The number of people in the group has a surprising effect. As the number increases, each person has less of an impact. A group's strength is how important the group is to a person. Groups we value generally have more social influence. Immediacy is how close the group is in time and space when the influence is taking place. Psychologists have constructed a mathematical model using these three factors and are able to predict the amount of conformity that occurs with some degree of accuracy.[43]

Baron and his colleagues conducted a second eyewitness study that focused on normative influence. In this version, the task was easier. Each participant had five seconds to look at a slide instead of just one second. Once again, there were both high and low motives to be accurate, but the results were the reverse of the first study. The low motivation group conformed 33% of the time (similar to Asch's findings). The high motivation group conformed less at 16%. These results show that when accuracy is not very important, it is better to get the wrong answer than to risk social disapproval.

An experiment using procedures similar to Asch's found that there was significantly less conformity in six-person groups of friends as compared to six-person groups of strangers.[44] Because friends already know and accept each other, there may be less normative pressure to conform in some situations. Field studies on cigarette and alcohol abuse, however, generally demonstrate evidence of friends exerting normative social influence on each other.[45]

Minority influence

[edit]Although conformity generally leads individuals to think and act more like groups, individuals are occasionally able to reverse this tendency and change the people around them. This is known as minority influence, a special case of informational influence. Minority influence is most likely when people can make a clear and consistent case for their point of view. If the minority fluctuates and shows uncertainty, the chance of influence is small. However, a minority that makes a strong, convincing case increases the probability of changing the majority's beliefs and behaviors.[46] Minority members who are perceived as experts, are high in status, or have benefited the group in the past are also more likely to succeed.

Another form of minority influence can sometimes override conformity effects and lead to unhealthy group dynamics. A 2007 review of two dozen studies by the University of Washington found that a single "bad apple" (an inconsiderate or negligent group member) can substantially increase conflicts and reduce performance in work groups. Bad apples often create a negative emotional climate that interferes with healthy group functioning. They can be avoided by careful selection procedures and managed by reassigning them to positions that require less social interaction.[47]

Specific predictors

[edit]Culture

[edit]

Stanley Milgram found that individuals in Norway (from a collectivistic culture) exhibited a higher degree of conformity than individuals in France (from an individualistic culture).[48][clarification needed] Similarly, Berry studied two different populations: the Temne (collectivists) and the Inuit (individualists) and found that the Temne conformed more than the Inuit when exposed to a conformity task.[49]

Bond and Smith compared 134 studies in a meta-analysis and found that there is a positive correlation between a country's level of collectivistic values and conformity rates in the Asch paradigm.[50] Bond and Smith also reported that conformity has declined in the United States over time.

Influenced by the writings of late-19th- and early-20th-century Western travelers, scholars or diplomats who visited Japan, such as Basil Hall Chamberlain, George Trumbull Ladd and Percival Lowell, as well as by Ruth Benedict's influential book The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, many scholars of Japanese studies speculated that there would be a higher propensity to conform in Japanese culture than in American culture. However, this view was not formed on the basis of empirical evidence collected in a systematic way, but rather on the basis of anecdotes and casual observations, which are subject to a variety of cognitive biases. Modern scientific studies comparing conformity in Japan and the United States show that Americans conform in general as much as the Japanese and, in some situations, even more. Psychology professor Yohtaro Takano from the University of Tokyo, along with Eiko Osaka reviewed four behavioral studies and found that the rate of conformity errors that the Japanese subjects manifested in the Asch paradigm was similar with that manifested by Americans.[51] The study published in 1970 by Robert Frager from the University of California, Santa Cruz found that the percentage of conformity errors within the Asch paradigm was significantly lower in Japan than in the United States, especially in the prize condition. Another study published in 2008, which compared the level of conformity among Japanese in-groups (peers from the same college clubs) with that found among Americans found no substantial difference in the level of conformity manifested by the two nations, even in the case of in-groups.[52]

Gender

[edit]Societal norms often establish gender differences and researchers have reported differences in the way men and women conform to social influence.[53][54][55][56][57][58][59] For example, Alice Eagly and Linda Carli performed a meta-analysis of 148 studies of influenceability. They found that women are more persuadable and more conforming than men in group pressure situations that involve surveillance.[60] Eagly has proposed that this sex difference may be due to different sex roles in society.[61] Women are generally taught to be more agreeable whereas men are taught to be more independent.

The composition of the group plays a role in conformity as well. In a study by Reitan and Shaw, it was found that men and women conformed more when there were participants of both sexes involved versus participants of the same sex. Subjects in the groups with both sexes were more apprehensive when there was a discrepancy amongst group members, and thus the subjects reported that they doubted their own judgments.[54] Sistrunk and McDavid made the argument that women conformed more because of a methodological bias.[62] They argued that because stereotypes used in studies are generally male ones (sports, cars..) more than female ones (cooking, fashion..), women felt uncertain and conformed more, which was confirmed by their results.

Age

[edit]Research has noted age differences in conformity. For example, research with Australian children and adolescents ages 3 to 17 discovered that conformity decreases with age.[63] Another study examined individuals that were ranged from ages 18 to 91.[64] The results revealed a similar trend – older participants displayed less conformity when compared to younger participants.

In the same way that gender has been viewed as corresponding to status, age has also been argued to have status implications. Berger, Rosenholtz and Zelditch suggest that age as a status role can be observed among college students. Younger students, such as those in their first year in college, are treated as lower-status individuals and older college students are treated as higher-status individuals.[65] Therefore, given these status roles, it would be expected that younger individuals (low status) conform to the majority whereas older individuals (high status) would be expected not to conform.[66]

Researchers have also reported an interaction of gender and age on conformity.[67] Eagly and Chrvala examined the role of age (under 19 years vs. 19 years and older), gender and surveillance (anticipating responses to be shared with group members vs. not anticipating responses being shared) on conformity to group opinions. They discovered that among participants that were 19 years or older, females conformed to group opinions more so than males when under surveillance (i.e., anticipated that their responses would be shared with group members). However, there were no gender differences in conformity among participants who were under 19 years of age and in surveillance conditions. There were also no gender differences when participants were not under surveillance. In a subsequent research article, Eagly suggests that women are more likely to conform than men because of lower status roles of women in society. She suggests that more submissive roles (i.e., conforming) are expected of individuals that hold low status roles.[66] Still, Eagly and Chrvala's results do conflict with previous research which have found higher conformity levels among younger rather than older individuals.

Size of the group

[edit]Although conformity pressures generally increase as the size of the majority increases, Asch's experiment in 1951 stated that increasing the size of the group will have no additional impact beyond a majority of size three.[68] Brown and Byrne's 1997 study described a possible explanation that people may suspect collusion when the majority exceeds three or four.[68] Gerard's 1968 study reported a linear relationship between the group size and conformity when the group size ranges from two to seven people.[69] According to Latane's 1981 study, the number of the majority is one factor that influences the degree of conformity, and there are other factors like strength and immediacy.[70]

Moreover, a study suggests that the effects of group size depend on the type of social influence operating.[71] This means that in situations where the group is clearly wrong, conformity will be motivated by normative influence; the participants will conform in order to be accepted by the group. A participant may not feel much pressure to conform when the first person gives an incorrect response. However, conformity pressure will increase as each additional group member also gives the same incorrect response.[71]

Situational factors

[edit]Research has found different group and situation factors that affect conformity. Accountability increases conformity, if an individual is trying to be accepted by a group which has certain preferences, then individuals are more likely to conform to match the group.[72] Similarly, the attractiveness of group members increases conformity. If an individual wishes to be liked by the group, they are increasingly likely to conform.[73]

Accuracy also effects conformity, as the more accurate and reasonable the majority is in their decision than the more likely the individual will be to conform.[74] As mentioned earlier, size also effects individuals' likelihood to conform.[33] The larger the majority the more likely an individual will conform to that majority. Similarly, the less ambiguous the task or decision is, the more likely someone will conform to the group.[75] When tasks are ambiguous people are less pressured to conform. Task difficulty also increases conformity, but research has found that conformity increases when the task is difficult but also important.[29]

Research has also found that as individuals become more aware that they disagree with the majority they feel more pressure, and hence are more likely to conform to the decisions of the group.[76] Likewise, when responses must be made face-face, individuals increasingly conform, and therefore conformity increases as the anonymity of the response in a group decreases. Conformity also increases when individuals have committed themselves to the group making decisions.[77]

Conformity has also been shown to be linked to cohesiveness. Cohesiveness is how strongly members of a group are linked together, and conformity has been found to increase as group cohesiveness increases.[78] Similarly, conformity is also higher when individuals are committed and wish to stay in the group. Conformity is also higher when individuals are in situations involving existential thoughts that cause anxiety, in these situations individuals are more likely to conform to the majority's decisions.[79]

Different stimuli

[edit]In 1961 Stanley Milgram published a study in which he utilized Asch's conformity paradigm using audio tones instead of lines; he conducted his study in Norway and France.[48] He found substantially higher levels of conformity than Asch, with participants conforming 50% of the time in France and 62% of the time in Norway during critical trials. Milgram also conducted the same experiment once more, but told participants that the results of the study would be applied to the design of aircraft safety signals. His conformity estimates were 56% in Norway and 46% in France, suggesting that individuals conformed slightly less when the task was linked to an important issue. Stanley Milgram's study demonstrated that Asch's study could be replicated with other stimuli, and that in the case of tones, there was a high degree of conformity.[80]

Neural correlates

[edit]Evidence has been found for the involvement of the posterior medial frontal cortex (pMFC) in conformity,[81] an area associated with memory and decision-making. For example, Klucharev et al.[82] revealed in their study that by using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on the pMFC, participants reduced their tendency to conform to the group, suggesting a causal role for the brain region in social conformity.

Neuroscience has also shown how people quickly develop similar values for things. Opinions of others immediately change the brain's reward response in the ventral striatum to receiving or losing the object in question, in proportion to how susceptible the person is to social influence. Having similar opinions to others can also generate a reward response.[80]

The amygdala and hippocampus have also been found to be recruited when individuals participated in a social manipulation experiment involving long-term memory.[83] Several other areas have further been suggested to play a role in conformity, including the insula, the temporoparietal junction, the ventral striatum, and the anterior and posterior cingulate cortices.[84][85][86][87][88]

More recent work[89] stresses the role of orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) in conformity not only at the time of social influence,[90] but also later on, when participants are given an opportunity to conform by selecting an action. In particular, Charpentier et al. found that the OFC mirrors the exposure to social influence at a subsequent time point, when a decision is being made without the social influence being present. The tendency to conform has also been observed in the structure of the OFC, with a greater grey matter volume in high conformers.[91]

See also

[edit]- Authoritarian personality

- Bandwagon effect

- Behavioral contagion

- Convention (norm)

- Conventional wisdom

- Countersignaling

- Cultural assimilation

- Honne and tatemae

- Knowledge falsification

- Milieu control

- Preference falsification

- Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes

- Spiral of silence

- Social inertia

References

[edit]- ^ Cialdini, Robert B.; Goldstein, Noah J. (February 2004). "Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity". Annual Review of Psychology. 55 (1): 591–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015. PMID 14744228. S2CID 18269933.

- ^ Infante; et al. (2010). Contemporary Communication Theory. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7575-5989-1.

- ^ Robinson, Eric; Thomas, Jason; Aveyard, Paul; Higgs, Suzanne (March 2014). "What Everyone Else Is Eating: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Informational Eating Norms on Eating Behavior". Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 114 (3): 414–429. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2013.11.009. PMID 24388484.

- ^ Chartrand, Tanya L. (1999). "The chameleon effect: The perception–behavior link and social interaction". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 76 (6): 893–910. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.6.893. PMID 10402679.

- ^ Larsen, Knud S. (1990). "The Asch Conformity Experiment: Replication and Transhistorical Comparison". Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 5 (4): 163–168. ProQuest 1292260764.

- ^ Coultas, Julie C.; Van Leeuwen, Edwin J. C. (2015). "Conformity: Definitions, Types, and Evolutionary Grounding". Evolutionary Perspectives on Social Psychology. Evolutionary Psychology. pp. 189–202. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12697-5_15. ISBN 978-3-319-12696-8.

- ^ a b Burger, Jerry M. (2019). "Conformity and Obedience". Introduction to Psychology.

- ^ a b Kassin, Saul M.; Fein, Steven; Markus, Hazel Rose (2011). Social Psychology. Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-8400-3172-3.[page needed]

- ^ Campbell, Jennifer D.; Fairey, Patricia J. (September 1989). "Informational and normative routes to conformity: The effect of faction size as a function of norm extremity and attention to the stimulus". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 57 (3): 457–468. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.457.

- ^ Biswas-Diener, Robert; Diener, Ed (2015). Discover Psychology 2.0: A Brief Introductory Text. University of Utah. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-674-01382-7.

- ^ McLeod, Saul (2016). "What is Conformity?". Simply Psychology.

- ^ Aronson, Elliot; Wilson, Timothy D.; Akert, Robin M. (2007). Social Psychology. Pearson Education International. ISBN 978-0-13-233487-7.[page needed]

- ^ L. G. (March 1931). "Conformity". Peabody Journal of Education. 8 (5): 312. doi:10.1080/01619563109535026. JSTOR 1488401.

- ^ Kamijo, Yoshio; Kira, Yosuke; Nitta, Kohei (December 2020). "Even Bad Social Norms Promote Positive Interactions". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 8694. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.8694K. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65516-w. PMC 7251124. PMID 32457329.

- ^ Abofol, Taher; Erev, Ido; Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Raanan (2023-08-05). "Conformity and Group Performance". Human Nature. 34 (3): 381–399. doi:10.1007/s12110-023-09454-2. ISSN 1936-4776. PMC 10543786. PMID 37541988.

- ^ a b c Kelman, Herbert C. (March 1958). "Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1177/002200275800200106. S2CID 145642577.

- ^ Kassin, Saul; Fein, Steven; Markus, Hazel Rose (2016). Social Psychology. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-305-58022-0. OCLC 965802335.[page needed]

- ^ a b Smith, Joanne R.; Louis, Winnifred R. (2009). "Group Norms and the Attitude-Behaviour Relationship: Group norms and attitude-behaviour relations" (PDF). Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 3 (1): 19–35. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00161.x. hdl:10036/49274.

- ^ Brown, Bradford (1986). "Perceptions of peer pressure, peer conformity dispositions, and self-reported behavior among adolescents". Developmental Psychology. 22 (4): 521–530. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.4.521.

- ^ a b Watson, T. Stuart; Skinner, Christopher H. (2004). Encyclopedia of School Psychology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-306-48480-3.

- ^ Ashford, Jose B.; LeCroy, Craig Winston (2009). Human Behavior in the Social Environment: A Multidimensional Perspective. Cengage Learning. p. 450. ISBN 978-0-495-60169-2.

- ^ Graupensperger, Scott A.; Benson, Alex J.; Evans, M. Blair (June 2018). "Everyone Else Is Doing It: The Association Between Social Identity and Susceptibility to Peer Influence in NCAA Athletes". Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 40 (3): 117–127. doi:10.1123/jsep.2017-0339. PMC 6399013. PMID 30001165.

- ^ Hill, Jennifer Ann (2016). How Consumer Culture Controls Our Kids: Cashing in on Conformity. ABC-CLIO. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4408-3482-0.

- ^ Myers, David G.; Twenge, Jean M. (2019). "Social Facilitation: How are we influenced by the presence of others?". Social Psychology. McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-1-260-39711-6.

- ^ "Moscovici and Minority Influence". Simply Psychology. Retrieved 2022-03-13.

- ^ a b Forsyth, D. R. (2013). Group dynamics. New York: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-1-133-95653-2. [Chapter 7]

- ^ Forsyth, Donelson R. (2008). "Autokinetic Effect". International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. 1 (2).

- ^ a b c Hogg, M. A.; Vaughan, G. M. (2005). Social psychology. Harlow: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

- ^ a b Baron, Robert S.; Vandello, Joseph A.; Brunsman, Bethany (November 1996). "The forgotten variable in conformity research: Impact of task importance on social influence". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 71 (5): 915–927. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.5.915.

- ^ a b c Asch, S. E. (1955). "Opinions and Social Pressure". Scientific American. 193 (5): 31–35. Bibcode:1955SciAm.193e..31A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1155-31. S2CID 4172915.

- ^ Guimond, Serge (2010). Psychologie sociale: perspective multiculturelle. Editions Mardaga. pp. 19–28. ISBN 978-2-8047-0032-4.

- ^ Asch, S. E. (1952). Social Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hal.

- ^ a b Asch, A. E. (1951). "Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgment". Groups, Leadership and Men: Research in Human Relations. Carnegie Press. pp. 177–190. ISBN 978-0-608-11271-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Milgram Experiment: Summary, Results, Conclusion, & Ethics". www.simplypsychology.org. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ Badhwar, Neera K. (September 2009). "The Milgram Experiments, Learned Helplessness, and Character Traits". The Journal of Ethics. 13 (2–3): 257–289. doi:10.1007/s10892-009-9052-4. ISSN 1382-4554. S2CID 144654674.

- ^ "The Stanford Prison Experiment: 40 Years Later".

- ^ Zimbardo, Philip G. (1973). "On the ethics of intervention in human psychological research: With special reference to the Stanford prison experiment" (PDF). Cognition. 2 (2): 243–256. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(72)90014-5. PMID 11662069. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-05-20.

- ^ a b Deutsch, Morton; Gerard, Harold B. (November 1955). "A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 51 (3): 629–636. doi:10.1037/h0046408. PMID 13286010. S2CID 35785090.

- ^ Stangor, Charles; Jhangiani, Rajiv; Tarry, Hammond (2022). "The Many Varieties of Conformity". Principles of Social Psychology.

- ^ Schachter, S (1951). "Deviation, Rejection, and communication". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 46 (2): 190–208. doi:10.1037/h0062326. PMID 14841000.

- ^ Hodges, B. H.; Geyer, A. L. (2006). "A Nonconformist Account of the Asch Experiments: Values, Pragmatics, and Moral Dilemmas". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 10 (1): 2–19. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_1. PMID 16430326. S2CID 24608338.

- ^ Latané, Bibb (April 1981). "The psychology of social impact". American Psychologist. 36 (4): 343–356. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.36.4.343. S2CID 145324374.

- ^ Latané, Bibb; Bourgeois, Martin J. (2001). "Successfully simulating dynamic social impact: Three levels of prediction". In Forgas, Joseph P.; Williams, Kipling D. (eds.). Social Influence: Direct and Indirect Processes. Psychology Press. pp. 61–76. ISBN 978-1-84169-038-4.

- ^ McKelvey, Wendy; Kerr, Nancy H. (June 1988). "Differences in Conformity among Friends and Strangers". Psychological Reports. 62 (3): 759–762. doi:10.2466/pr0.1988.62.3.759. S2CID 145481141.

- ^ Urberg, Kathryn A.; Değirmencioğlu, Serdar M.; Pilgrim, Colleen (1997). "Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use". Developmental Psychology. 33 (5): 834–844. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.33.5.834. PMID 9300216.

- ^ Moscovici, S. N. (1974). "Minority influence". In Nemeth, Charlan (ed.). Social Psychology: Classic and Contemporary Integrations. Rand McNally. pp. 217–249. ISBN 978-0-528-62955-6.

- ^ Felps, Will; Mitchell, Terence R.; Byington, Eliza (2006). "How, When, and Why Bad Apples Spoil the Barrel: Negative Group Members and Dysfunctional Groups". Research in Organizational Behavior. 27: 175–222. doi:10.1016/S0191-3085(06)27005-9.

- ^ a b Milgram, Stanley (December 1961). "Nationality and Conformity". Scientific American. 205 (6): 45–51. Bibcode:1961SciAm.205f..45M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1261-45.

- ^ Berry, J. W. (1967). "Independence and conformity in subsistence-level societies". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 7 (4, Pt.1): 415–418. doi:10.1037/h0025231. PMID 6065870.

- ^ Bond, Rod; Smith, Peter B. (January 1996). "Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch's (1952b, 1956) line judgment task". Psychological Bulletin. 119 (1): 111–137. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.111. S2CID 17823166.

- ^ Takano, Yohtaro; Osaka, Eiko (December 1999). "An unsupported common view: Comparing Japan and the U.S. on individualism/collectivism". Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2 (3): 311–341. doi:10.1111/1467-839X.00043.

- ^ Takano, Yohtaro; Sogon, Shunya (May 2008). "Are Japanese More Collectivistic Than Americans?: Examining Conformity in In-Groups and the Reference-Group Effect". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 39 (3): 237–250. doi:10.1177/0022022107313902. S2CID 145125365.

- ^ Bond, Rod; Smith, Peter B. (January 1996). "Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch's (1952b, 1956) line judgment task". Psychological Bulletin. 119 (1): 111–137. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.111. S2CID 17823166. ProQuest 614318101.

- ^ a b Reitan, H; Shaw, M (1964). "Group Membership, Sex-Composition of the Group, and Conformity Behavior". The Journal of Social Psychology. 64: 45–51. doi:10.1080/00224545.1964.9919541. PMID 14217456.

- ^ Applezweig, M H; Moeller, G (1958). Conforming behavior and personality variables. New London: Connecticut College.

- ^ Beloff, H (1958). "Two forms of social conformity: Acquiescence and conventionality". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 56 (1): 99–104. doi:10.1037/h0046604. PMID 13501978.

- ^ Coleman, J; Blake, R R; Mouton, J S (1958). "Task difficulty and conformity pressures". The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 57 (1): 120–122. doi:10.1037/h0041274. PMID 13563057.

- ^ Cooper, H.M. (1979). "Statistically combining independent studies: A meta-analysis of sex differences in conformity research". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37: 131–146. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.1.131.

- ^ Eagly, A.H. (1978). "Sex differences in influenceability". Psychological Bulletin. 85: 86–116. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.85.1.86.

- ^ Eagly, A. H; Carli, L. L (1981). "Sex of researchers and sex-typed communications as determinants of sex differences in influenceability: A meta-analysis of social influence studies". Psychological Bulletin. 90 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.90.1.1.

- ^ Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ^ Sistrunk, F; McDavid, J. W (1971). "Sex variable in conforming behavior". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 17 (2): 200–207. doi:10.1037/h0030382.

- ^ Walker, Michael B.; Andrade, Maria G. (June 1996). "Conformity in the Asch Task as a Function of Age". The Journal of Social Psychology. 136 (3): 367–372. doi:10.1080/00224545.1996.9714014. PMID 8758616.

- ^ Pasupathi, Monisha (1999). "Age differences in response to conformity pressure for emotional and nonemotional material". Psychology and Aging. 14 (1): 170–174. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.14.1.170. PMID 10224640.

- ^ Berger, Joseph; Rosenholtz, Susan J.; Zelditch, Morris (August 1980). "Status Organizing Processes". Annual Review of Sociology. 6 (1): 479–508. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.06.080180.002403. hdl:1969.1/154809.

- ^ a b Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W. (1982). "Inferred sex differences in status as a determinant of gender stereotypes about social influence". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 43 (5): 915–928. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.43.5.915.

- ^ Eagly, Alice H.; Chrvala, Carole (September 1986). "Sex Differences in Conformity: Status and Gender Role Interpretations". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 10 (3): 203–220. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1986.tb00747.x. S2CID 146308947.

- ^ a b "Asch Conformity Experiment". Simply Psychology. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- ^ Sasaki, Shusaku (2017). "Group size and conformity in charitable giving: Evidence from a donation-based crowdfunding platform in Japan". ISER Discussion Papers. No. 1004. hdl:10419/197733 – via EconStor.

- ^ Latané, Bibb; Wolf, Sharon (September 1981). "The social impact of majorities and minorities". Psychological Review. 88 (5): 438–453. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.88.5.438. S2CID 145479428.

- ^ a b Campbell, J. D.; Fairey, P. J. (1989). "Informational and normative routes to conformity: The effect of faction size as a function of norm extremity and attention to the stimulus". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 57 (3): 457–468. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.457.

- ^ Quinn, Andrew; Schlenker, Barry R. (April 2002). "Can Accountability Produce Independence? Goals as Determinants of the Impact of Accountability on Conformity". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 28 (4): 472–483. doi:10.1177/0146167202287005. S2CID 145630626.

- ^ Kiesler, Charles A.; Corbin, Lee H. (1965). "Commitment, attraction, and conformity". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2 (6): 890–895. doi:10.1037/h0022730. PMID 5838495.

- ^ Forsyth, Donelson R. (2015). Group Dynamics. Cengage Learning. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-1-133-95653-2.

- ^ Spencer, Roger W.; Huston, John H. (December 1993). "Rational forecasts: On confirming ambiguity as the mother of conformity". Journal of Economic Psychology. 14 (4): 697–709. doi:10.1016/0167-4870(93)90017-f.

- ^ Clement, Russell W.; Sinha, Rashmi R.; Krueger, Joachim (April 1997). "A Computerized Demonstration of the False Consensus Effect". Teaching of Psychology. 24 (2): 131–135. doi:10.1207/s15328023top2402_12. S2CID 144175960.

- ^ Kiesler, Charles A.; Zanna, Mark; Desalvo, James (1966). "Deviation and conformity: Opinion change as a function of commitment, attraction, and presence of a deviate". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 3 (4): 458–467. doi:10.1037/h0023027. PMID 5909118.

- ^ Forsyth, Donelson R. (2015). Group Dynamics. Cengage Learning. pp. 116–142. ISBN 978-1-133-95653-2.

- ^ Renkema, Lennart J.; Stapel, Diederik A.; Van Yperen, Nico W. (June 2008). "Go with the flow: conforming to others in the face of existential threat". European Journal of Social Psychology. 38 (4): 747–756. doi:10.1002/ejsp.468. S2CID 145013998.

- ^ a b Campbell-Meiklejohn, Daniel K.; Bach, Dominik R.; Roepstorff, Andreas; Dolan, Raymond J.; Frith, Chris D. (July 2010). "How the Opinion of Others Affects Our Valuation of Objects". Current Biology. 20 (13): 1165–1170. Bibcode:2010CBio...20.1165C. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.055. PMC 2908235. PMID 20619815.

- ^ Izuma, K (2013). "The neural basis of social influence and attitude change". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 23 (3): 456–462. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2013.03.009. PMID 23608704. S2CID 12160803.

- ^ Klucharev, V.; Munneke, M. A.; Smidts, A.; Fernández, G. (2011). "Downregulation of the posterior medial frontal cortex prevents social conformity". The Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (33): 11934–11940. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1869-11.2011. PMC 6623179. PMID 21849554.

- ^ Edelson, M.; Sharot, T.; Dolan, R. J.; Dudai, Y. (2011). "Following the crowd: brain substrates of long-term memory conformity". Science. 333 (6038): 108–111. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..108E. doi:10.1126/science.1203557. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-A26C-F. PMC 3284232. PMID 21719681.

- ^ Stallen, M.; Smidts, A.; Sanfey, A. G. (2013). "Peer influence: neural mechanisms underlying in-group conformity". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 7: 50. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00050. PMC 3591747. PMID 23482688.

- ^ Falk, E. B.; Way, B. M.; Jasinska, A. J. (2012). "An imaging genetics approach to understanding social influence". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 6: 168. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2012.00168. PMC 3373206. PMID 22701416.

- ^ Berns, G. S.; Chappelow, J.; Zink, C. F.; Pagnoni, G.; Martin-Skurski, M. E.; Richards, J. (2005). "Neurobiological correlates of social conformity and independence during mental rotation". Biological Psychiatry. 58 (3): 245–253. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.012. PMID 15978553. S2CID 10355223.

- ^ Berns, G. S.; Capra, C. M.; Moore, S.; Noussair, C. (2010). "Neural mechanisms of the influence of popularity on adolescent ratings of music". NeuroImage. 49 (3): 2687–2696. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.070. PMC 2818406. PMID 19879365.

- ^ Burke, C. J.; Tobler, P. N.; Schultz, W.; Baddeley, M. (2010). "Striatal BOLD response reflects the impact of herd information on financial decisions". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 4: 48. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2010.00048. PMC 2892997. PMID 20589242.

- ^ Charpentier, C.; Moutsiana, C.; Garrett, N.; Sharot, T. (2014). "The Brain's Temporal Dynamics from a Collective Decision to Individual Action". Journal of Neuroscience. 34 (17): 5816–5823. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4107-13.2014. PMC 3996210. PMID 24760841.

- ^ Zaki, J.; Schirmer, J.; Mitchell, J. P. (2011). "Social influence modulates the neural computation of value". Psychological Science. 22 (7): 894–900. doi:10.1177/0956797611411057. PMID 21653908. S2CID 7422242.

- ^ Campbell-Meiklejohn, D. K.; Kanai, R.; Bahrami, B.; Bach, D. R.; Dolan, R. J.; Roepstorff, A.; Frith, C. D. (2012). "Structure of orbitofrontal cortex predicts social influence". Current Biology. 22 (4): R123 – R124. Bibcode:2012CBio...22.R123C. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.012. PMC 3315000. PMID 22361146.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Conformity at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Conformity at Wikiquote