Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

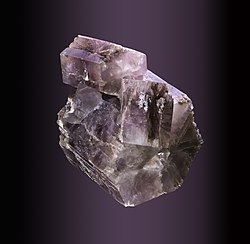

Crystal polymorphism

View on WikipediaIn crystallography, polymorphism is the phenomenon where a compound or element can crystallize into more than one crystal structure.

The preceding definition has evolved over many years and is still under discussion today.[1][2][3] Discussion of the defining characteristics of polymorphism involves distinguishing among types of transitions and structural changes occurring in polymorphism versus those in other phenomena.

Overview

[edit]Phase transitions (phase changes) that help describe polymorphism include polymorphic transitions as well as melting and vaporization transitions. According to IUPAC, a polymorphic transition is "A reversible transition of a solid crystalline phase at a certain temperature and pressure (the inversion point) to another phase of the same chemical composition with a different crystal structure."[4] Additionally, Walter McCrone described the phases in polymorphic matter as "different in crystal structure but identical in the liquid or vapor states." McCrone also defines a polymorph as "a crystalline phase of a given compound resulting from the possibility of at least two different arrangements of the molecules of that compound in the solid state."[5][6] These defining facts imply that polymorphism involves changes in physical properties but cannot include chemical change. Some early definitions do not make this distinction.

Eliminating chemical change from those changes permissible during a polymorphic transition delineates polymorphism. For example, isomerization can often lead to polymorphic transitions. However, tautomerism (dynamic isomerization) leads to chemical change, not polymorphism.[1] As well, allotropy of elements and polymorphism have been linked historically. However, allotropes of an element are not always polymorphs. A common example is the allotropes of carbon, which include graphite, diamond, and londsdaleite. While all three forms are allotropes, graphite is not a polymorph of diamond and londsdaleite. Isomerization and allotropy are only two of the phenomena linked to polymorphism. For additional information about identifying polymorphism and distinguishing it from other phenomena, see the review by Brog et al.[2]

It is also useful to note that materials with two polymorphic phases can be called dimorphic, those with three polymorphic phases, trimorphic, etc.[7]

Polymorphism is of practical relevance to pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, pigments, dyestuffs, foods, and explosives.

Detection

[edit]Experimental methods

[edit]Early records of the discovery of polymorphism credit Eilhard Mitscherlich and Jöns Jacob Berzelius for their studies of phosphates and arsenates in the early 1800s. The studies involved measuring the interfacial angles of the crystals to show that chemically identical salts could have two different forms. Mitscherlich originally called this discovery isomorphism.[8] The measurement of crystal density was also used by Wilhelm Ostwald and expressed in Ostwald's Ratio.[9]

The development of the microscope enhanced observations of polymorphism and aided Moritz Ludwig Frankenheim's studies in the 1830s. He was able to demonstrate methods to induce crystal phase changes and formally summarized his findings on the nature of polymorphism. Soon after, the more sophisticated polarized light microscope came into use, and it provided better visualization of crystalline phases allowing crystallographers to distinguish between different polymorphs. The hot stage was invented and fitted to a polarized light microscope by Otto Lehmann in about 1877. This invention helped crystallographers determine melting points and observe polymorphic transitions.[8]

While the use of hot stage microscopes continued throughout the 1900s, thermal methods also became commonly used to observe the heat flow that occurs during phase changes such as melting and polymorphic transitions. One such technique, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), continues to be used for determining the enthalpy of polymorphic transitions.[8]

In the 20th century, X-ray crystallography became commonly used for studying the crystal structure of polymorphs. Both single crystal x-ray diffraction and powder x-ray diffraction techniques are used to obtain measurements of the crystal unit cell. Each polymorph of a compound has a unique crystal structure. As a result, different polymorphs will produce different x-ray diffraction patterns.[8]

Vibrational spectroscopic methods came into use for investigating polymorphism in the second half of the twentieth century and have become more commonly used as optical, computer, and semiconductor technologies improved. These techniques include infrared (IR) spectroscopy, terahertz spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy. Mid-frequency IR and Raman spectroscopies are sensitive to changes in hydrogen bonding patterns. Such changes can subsequently be related to structural differences. Additionally, terahertz and low frequency Raman spectroscopies reveal vibrational modes resulting from intermolecular interactions in crystalline solids. Again, these vibrational modes are related to crystal structure and can be used to uncover differences in 3-dimensional structure among polymorphs.[10]

Computational methods

[edit]Computational chemistry may be used in combination with vibrational spectroscopy techniques to understand the origins of vibrations within crystals.[10] The combination of techniques provides detailed information about crystal structures, similar to what can be achieved with x-ray crystallography. In addition to using computational methods for enhancing the understanding of spectroscopic data, the latest development in identifying polymorphism in crystals is the field of crystal structure prediction. This technique uses computational chemistry to model the formation of crystals and predict the existence of specific polymorphs of a compound before they have been observed experimentally by scientists.[11][12]

Beyond the experimental possibilities, computational methods have been employed to study atomistic changes in crystal structures at varying temperatures and under different atmospheres. In the case of porous materials, the presence of guest molecules can induce guest-specific structural phases.[13]

Examples

[edit]Many compounds exhibit polymorphism. It has been claimed that "every compound has different polymorphic forms, and that, in general, the number of forms known for a given compound is proportional to the time and money spent in research on that compound."[14][5][15]

Organic compounds

[edit]Benzamide

[edit]The phenomenon was discovered in 1832 by Friedrich Wöhler and Justus von Liebig. They observed that the silky needles of freshly crystallized benzamide slowly converted to rhombic crystals.[16] Present-day analysis[17] identifies three polymorphs for benzamide: the least stable one, formed by flash cooling, is the orthorhombic form II. This type is followed by the monoclinic form III (observed by Wöhler/Liebig). The most stable form is monoclinic form I. The hydrogen bonding mechanisms are the same for all three phases; however, they differ strongly in their pi-pi interactions.

Maleic acid

[edit]In 2006 a new polymorph of maleic acid was discovered, 124 years after the first crystal form was studied. Maleic acid is manufactured on an industrial scale in the chemical industry. It forms salt found in medicine. The new crystal type is produced when a co-crystal of caffeine and maleic acid (2:1) is dissolved in chloroform and when the solvent is allowed to evaporate slowly. Whereas form I has monoclinic space group P21/c, the new form has space group Pc. Both polymorphs consist of sheets of molecules connected through hydrogen bonding of the carboxylic acid groups: in form I, the sheets alternate with respect of the net dipole moment, while in form II, the sheets are oriented in the same direction.[18]

1,3,5-Trinitrobenzene

[edit]After 125 years of study, 1,3,5-trinitrobenzene yielded a second polymorph. The usual form has the space group Pbca, but in 2004, a second polymorph was obtained in the space group Pca21 when the compound was crystallised in the presence of an additive, trisindane. This experiment shows that additives can induce the appearance of polymorphic forms.[19]

Other organic compounds

[edit]Acridine has been obtained as eight polymorphs[20] and aripiprazole has nine.[21] The record for the largest number of well-characterised polymorphs is held by a compound known as ROY.[22][23] Glycine crystallizes as both monoclinic and hexagonal crystals. Polymorphism in organic compounds is often the result of conformational polymorphism.[24]

Inorganic matter

[edit]Elements

[edit]Elements including metals may exhibit polymorphism. Allotropy is the term used when describing elements having different forms and is used commonly in the field of metallurgy. Some (but not all) allotropes are also polymorphs. For example, iron has three allotropes that are also polymorphs. Alpha-iron, which exists at room temperature, has a bcc form. Above 910 degrees gamma-iron exists, which has a fcc form. Above 1390 degrees delta-iron exists with a bcc form.[25]

Another metallic example is tin, which has two allotropes that are also polymorphs. At room temperature, beta-tin exists as a white tetragonal form. When cooled below 13.2 degrees, alpha-tin forms which is gray in color and has a cubic diamond form.[25]

A classic example of a nonmetal that exhibits polymorphism is carbon. Carbon has many allotropes, including graphite, diamond, and londsdaleite. However, these are not all polymorphs of each other. Graphite is not a polymorph of diamond and londsdaleite, since it is chemically distinct, having sp2 hybridized bonding. Diamond and londsdaleite are chemically identical, both having sp3 hybridized bonding, and they differ only in their crystal structures, making them polymorphs. Additionally, graphite has two polymorphs, a hexagonal (alpha) form and a rhombohedral (beta) form.[25]

Binary metal oxides

[edit]Polymorphism in binary metal oxides has attracted much attention because these materials are of significant economic value. One set of famous examples have the composition SiO2, which form many polymorphs. Important ones include: α-quartz, β-quartz, tridymite, cristobalite, moganite, coesite, and stishovite.[26] [27]

| Metal oxides | Phase | Conditions of P and T | Structure/Space Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| CrO2 | α phase | Ambient conditions | Cl2-type Orthorhombic |

| RT and 12±3 GPa | |||

| Cr2O3 | Corundum phase | Ambient conditions | Corundum-type Rhombohedral (R3c) |

| High pressure phase | RT and 35 GPa | Rh2O3-II type | |

| Fe2O3 | α phase | Ambient conditions | Corundum-type Rhombohedral (R3c) |

| β phase | Below 773 K | Body-centered cubic (Ia3) | |

| γ phase | Up to 933 K | Cubic spinel structure (Fd3m) | |

| ε phase | -- | Rhombic (Pna21) | |

| Bi2O3 | α phase | Ambient conditions | Monoclinic (P21/c) |

| β phase | 603-923 K and 1 atm | Tetragonal | |

| γ phase | 773-912 K or RT and 1 atm | Body-centered cubic | |

| δ phase | 912-1097 K and 1 atm | FCC (Fm3m) | |

| In2O3 | Bixbyite-type phase | Ambient conditions | Cubic (Ia3) |

| Corundum-type | 15-25 GPa at 1273 K | Corundum-type Hexagonal (R3c) | |

| Rh2O3(II)-type | 100 GPa and 1000 K | Orthorhombic | |

| Al2O3 | α phase | Ambient conditions | Corundum-type Trigonal (R3c) |

| γ phase | 773 K and 1 atm | Cubic (Fd3m) | |

| SnO2 | α phase | Ambient conditions | Rutile-type Tetragonal (P42/mnm) |

| CaCl2-type phase | 15 KBar at 1073 K | Orthorhombic, CaCl2-type (Pnnm) | |

| α-PbO2-type | Above 18 KBar | α-PbO2-type (Pbcn) | |

| TiO2 | Rutile | Equilibrium phase | Rutile-type Tetragonal |

| Anatase | Metastable phase (Not stable)[28] | Tetragonal (I41/amd) | |

| Brookite | Metastable phase (Not stable)[28] | Orthorhombic (Pcab) | |

| ZrO2 | Monoclinic phase | Ambient conditions | Monoclinic (P21/c) |

| Tetragonal phase | Above 1443 K | Tetragonal (P42/nmc) | |

| Fluorite-type phase | Above 2643 K | Cubic (Fm3m) | |

| MoO3 | α phase | 553-673 K & 1 atm | Orthorhombic (Pbnm) |

| β phase | 553-673 K & 1 atm | Monoclinic | |

| h phase | High-pressure and high-temperature phase | Hexagonal (P6a/m or P6a) | |

| MoO3-II | 60 kbar and 973 K | Monoclinic | |

| WO3 | ε phase | Up to 220 K | Monoclinic (Pc) |

| δ phase | 220-300 K | Triclinic (P1) | |

| γ phase | 300-623 K | Monoclinic (P21/n) | |

| β phase | 623-900 K | Orthorhombic (Pnma) | |

| α phase | Above 900 K | Tetragonal (P4/ncc) |

Other inorganic compounds

[edit]A classical example of polymorphism is the pair of minerals calcite, which is rhombohedral, and aragonite, which is orthorhombic. Both are forms of calcium carbonate.[25] A third form of calcium carbonate is vaterite, which is hexagonal and relatively unstable.[29]

β-HgS precipitates as a black solid when Hg(II) salts are treated with H2S. With gentle heating of the slurry, the black polymorph converts to the red form.[30]

Factors affecting polymorphism

[edit]According to Ostwald's rule, usually less stable polymorphs crystallize before the stable form. The concept hinges on the idea that unstable polymorphs more closely resemble the state in solution, and thus are kinetically advantaged. The founding case of fibrous vs rhombic benzamide illustrates the case. Another example is provided by two polymorphs of titanium dioxide.[28] Nevertheless, there are known systems, such as metacetamol, where only narrow cooling rate favors obtaining metastable form II.[31]

Polymorphs have disparate stabilities. Some convert rapidly at room (or any) temperature. Most polymorphs of organic molecules only differ by a few kJ/mol in lattice energy. Approximately 50% of known polymorph pairs differ by less than 2 kJ/mol and stability differences of more than 10 kJ/mol are rare.[32] Polymorph stability may change upon temperature[33][34][35] or pressure.[36][37] Importantly, structural and thermodynamic stability are different. Thermodynamic stability may be studied using experimental or computational methods.[38][39]

Polymorphism is affected by the details of crystallisation. The solvent in all respects affects the nature of the polymorph, including concentration, other components of the solvent, i.e., species that inhibiting or promote certain growth patterns.[40] A decisive factor is often the temperature of the solvent from which crystallisation is carried out.[41]

Metastable polymorphs are not always reproducibly obtained, leading to cases of "disappearing polymorphs", with usually negative implications on law and business.[14][11][42]

In pharmaceuticals

[edit]Approximately 37% or more of organic compounds exist as more than one polymorph.[43] The existence of polymorphs has legal implications as drugs receive regulatory approval and are granted patents for only a single polymorph. In a classic patent dispute, the GlaxoSmithKline defended its patent for the Type II polymorph of the active ingredient in Zantac against competitors while that of the Type I polymorph had already expired.[44] Polymorphism in drugs can also have direct medical implications since dissolution rates depend on the polymorph. The known cases up to 2015 are discussed in a review article by Bučar, Lancaster, and Bernstein.[11]

Dibenzoxazepines

[edit]Clozapine exists in 4 forms compared to 60 forms for olanzapine.[45]

Posaconazole

[edit]The original formulations licensed as Noxafil were formulated utilising form I of posaconazole. The discovery of polymorphs of posaconazole increased rapidly and resulted in much research in crystallography of posaconazole. A methanol solvate and a 1,4-dioxane co-crystal were added to the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD).[46]

Ritonavir

[edit]The antiviral drug ritonavir exists as two polymorphs, which differ greatly in efficacy. Such issues were solved by reformulating the medicine into gelcaps and tablets, rather than the original capsules.[47]

Aspirin

[edit]One polymorph ("Form I") of aspirin is common.[11] "Form II" was reported in 2005,[48][49] found after attempted co-crystallization of aspirin and levetiracetam from hot acetonitrile.

In form I, pairs of aspirin molecules form centrosymmetric dimers through the acetyl groups with the (acidic) methyl proton to carbonyl hydrogen bonds. In form II, each aspirin molecule forms the same hydrogen bonds, but with two neighbouring molecules instead of one. With respect to the hydrogen bonds formed by the carboxylic acid groups, both polymorphs form identical dimer structures. The aspirin polymorphs contain identical 2-dimensional sections and are therefore more precisely described as polytypes.[50]

Pure Form II aspirin could be prepared by seeding the batch with aspirin anhydrate in 15% weight.[11]

Paracetamol

[edit]Paracetamol powder has poor compression properties, which poses difficulty in making tablets. A second polymorph was found with more suitable compressive properties.[51]

Cortisone acetate

[edit]Cortisone acetate exists in at least five different polymorphs, four of which are unstable in water and change to a stable form.

Carbamazepine

[edit]Carbamazepine, estrogen, paroxetine,[52] and chloramphenicol also show polymorphism.

Pyrazinamide

[edit]Pyrazinamide has at least 4 polymorphs.[53] All of them transforms to stable α form at room temperature upon storage or mechanical treatment.[54] Recent studies prove that α form is thermodynamically stable at room temperature.[33][35]

Polytypism

[edit]Polytypes are a special case of polymorphs, where multiple close-packed crystal structures differ in one dimension only. Polytypes have identical close-packed planes, but differ in the stacking sequence in the third dimension perpendicular to these planes. Silicon carbide (SiC) has more than 170 known polytypes, although most are rare. All the polytypes of SiC have virtually the same density and Gibbs free energy. The most common SiC polytypes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Some polytypes of SiC.[55]

| Phase | Structure | Ramsdell notation | Stacking sequence | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-SiC | hexagonal | 2H | AB | wurtzite form |

| α-SiC | hexagonal | 4H | ABCB | |

| α-SiC | hexagonal | 6H | ABCACB | the most stable and common form |

| α-SiC | rhombohedral | 15R | ABCACBCABACABCB | |

| β-SiC | face-centered cubic | 3C | ABC | sphalerite or zinc blende form |

A second group of materials with different polytypes are the transition metal dichalcogenides, layered materials such as molybdenum disulfide (MoS2). For these materials the polytypes have more distinct effects on material properties, e.g. for MoS2, the 1T polytype is metallic in character, while the 2H form is more semiconducting.[56] Another example is tantalum disulfide, where the common 1T as well as 2H polytypes occur, but also more complex 'mixed coordination' types such as 4Hb and 6R, where the trigonal prismatic and the octahedral geometry layers are mixed.[57] Here, the 1T polytype exhibits a charge density wave, with distinct influence on the conductivity as a function of temperature, while the 2H polytype exhibits superconductivity.

ZnS and CdI2 are also polytypical.[58] It has been suggested that this type of polymorphism is due to kinetics where screw dislocations rapidly reproduce partly disordered sequences in a periodic fashion.

Theory

[edit]

In terms of thermodynamics, two types of polymorphic behaviour are recognized. For a monotropic system, plots of the free energies of the various polymorphs against temperature do not cross before all polymorphs melt. As a result, any transition from one polymorph to another below the melting point will be irreversible. For an enantiotropic system, a plot of the free energy against temperature shows a crossing point before the various melting points.[59] It may also be possible to convert interchangeably between the two polymorphs by heating or cooling, or through physical contact with a lower energy polymorph.

A simple model of polymorphism is to model the Gibbs free energy of a ball-shaped crystal as . Here, the first term is the surface energy, and the second term is the volume energy. Both parameters . The function rises to a maximum before dropping, crossing zero at . In order to crystallize, a ball of crystal much overcome the energetic barrier to the part of the energy landscape.[60]

Now, suppose there are two kinds of crystals, with different energies and , and if they have the same shape as in Figure 2, then the two curves intersect at some . Then the system has three phases:

- . Crystals tend to dissolve. Amorphous phase.

- . Crystals tend to grow as form 1.

- . Crystals tend to grow as form 2.

If the crystal is grown slowly, it could be kinetically stuck in form 1.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Bernstein, Joel (2002). Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals. New York, USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–27. ISBN 0198506058.

- ^ a b Brog, Jean-Pierre; Chanez, Claire-Lise; Crochet, Aurelien; Fromm, Katharina M. (2013). "Polymorphism, what it is and how to identify it: a systematic review". RSC Advances. 3 (38): 16905–31. Bibcode:2013RSCAd...316905B. doi:10.1039/c3ra41559g.

- ^ Cruz-Cabeza, Aurora J.; Reutzel-Edens, Susan M.; Bernstein, Joel (2015). "Facts and fictions about polymorphism". Chemical Society Reviews. 44 (23): 8619–8635. doi:10.1039/c5cs00227c. PMID 26400501 – via MEDLINE.

- ^ Gold, Victor, ed. (2019). "Polymorphic transition". IUPAC Gold Book. doi:10.1351/goldbook. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ a b McCrone, W. C. (1965). "Polymorphism". In Fox, D.; Labes, M.; Weissberger, A. (eds.). Physics and Chemistry of the Organic Solid State. Vol. 2. Wiley-Interscience. pp. 726–767.

- ^ Dunitz, Jack D.; Bernstein, Joel (1995-04-01). "Disappearing Polymorphs". Accounts of Chemical Research. 28 (4): 193–200. doi:10.1021/ar00052a005. ISSN 0001-4842.

- ^ "Definition of trimorphism - mindat.org glossary". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ a b c d Bernstein, Joel (2002). Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals. New York, USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 94–149. ISBN 0198506058.

- ^ Cardew, Peter T. (2023). "Ostwald Rule of Stages - Myth or Reality?". Crystal Growth & Design. 23 (6): 3958−3969. Bibcode:2023CrGrD..23.3958C. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.2c00141.

- ^ a b Parrott, Edward P.J.; Zeitler, J. Axel (2015). "Terahertz Time-Domain and Low-Frequency Raman Spectroscopy of Organic Materials". Applied Spectroscopy. 69 (1): 1–25. Bibcode:2015ApSpe..69....1P. doi:10.1366/14-07707. PMID 25506684. S2CID 7699996.

- ^ a b c d e Bučar, D.-K.; Lancaster, R. W.; Bernstein, J. (2015). "Disappearing Polymorphs Revisited". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 54 (24): 6972–6993. doi:10.1002/anie.201410356. PMC 4479028. PMID 26031248.

- ^ Bowskill, David H.; Sugden, Isaac J.; Konstantinopoulos, Stefanos; Adjiman, Claire S.; Pantelides, Constantinos C. (2021). "Crystal Structure Prediction Methods for Organic Molecules: State of the Art". Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 12: 593–623. doi:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-060718-030256. PMID 33770462. S2CID 232377397.

- ^ Stracke, K; Evans, JD (2025). "Investigating the Temperature-Induced Expansion of MIL-53 under Different Gas Environments Using Molecular Simulations". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 129 (6): 3226–3233. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.4c10584.

- ^ a b Crystal Engineering: The Design and Application of Functional Solids, Volume 539, Kenneth Richard Seddon, Michael Zaworotk 1999

- ^ Pharmaceutical Stress Testing: Predicting Drug Degradation, Second Edition Steven W. Baertschi, Karen M. Alsante, Robert A. Reed 2011 CRC Press

- ^ Wöhler, F.; Liebig, J.; Ann (1832). "Untersuchungen über das Radikal der Benzoesäure". Annalen der Pharmacie (in German). 3 (3). Wiley: 249–282. doi:10.1002/jlac.18320030302. hdl:2027/hvd.hxdg3f. ISSN 0365-5490.

- ^ Thun, Jürgen (2007). "Polymorphism in Benzamide: Solving a 175-Year-Old Riddle". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 46 (35): 6729–6731. doi:10.1002/anie.200701383. PMID 17665385.

- ^ Graeme M. Day; Andrew V. Trask; W. D. Samuel Motherwell; William Jones (2006). "Investigating the Latent Polymorphism of Maleic Acid". Chemical Communications. 1 (1): 54–56. doi:10.1039/b513442k. PMID 16353090.

- ^ Thallapally PK, Jetti RK, Katz AK (2004). "Polymorphism of 1,3,5-trinitrobenzene Induced by a Trisindane Additive". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 43 (9): 1149–1155. doi:10.1002/anie.200352253. PMID 14983460.

- ^ Schur, Einat; Bernstein, Joel; Price, Louise S.; Guo, Rui; Price, Sarah L.; Lapidus, Saul H.; Stephens, Peter W. (2019). "The (Current) Acridine Solid Form Landscape: Eight Polymorphs and a Hydrate" (PDF). Crystal Growth & Design. 19 (8): 4884–4893. Bibcode:2019CrGrD..19.4884S. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.9b00557. S2CID 198349955.

- ^ Serezhkin, Viktor N.; Savchenkov, Anton V. (2020). "Application of the Method of Molecular Voronoi–Dirichlet Polyhedra for Analysis of Noncovalent Interactions in Aripiprazole Polymorphs". Crystal Growth & Design. 20 (3): 1997–2003. Bibcode:2020CrGrD..20.1997S. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.9b01645. S2CID 213824513.

- ^ Krämer, Katrina (2020-07-29). "Red–orange–yellow reclaims polymorph record with help from molecular cousin". chemistryworld.com. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ Tyler, Andrew R.; Ragbirsingh, Ronnie; McMonagle, Charles J.; Waddell, Paul G.; Heaps, Sarah E.; Steed, Jonathan W.; Thaw, Paul; Hall, Michael J.; Probert, Michael R. (2020). "Encapsulated Nanodroplet Crystallization of Organic-Soluble Small Molecules". Chem. 6 (7): 1755–1765. Bibcode:2020Chem....6.1755T. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2020.04.009. PMC 7357602. PMID 32685768.

- ^ Cruz-Cabeza, Aurora J.; Bernstein, Joel (2014). "Conformational Polymorphism". Chemical Reviews. 114 (4): 2170–2191. doi:10.1021/cr400249d. PMID 24350653.

- ^ a b c d Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (Second ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- ^ "Definition of polymorphism - mindat.org glossary". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ "Polymorphism in nanocrystalline binary metal oxides", S. Sood, P.Gouma, Nanomaterials and Energy, 2(NME2), 1-15(2013).

- ^ a b c Anatase to Rutile Transformation(ART) summarized in the Journal of Materials Science 2011

- ^ Perić, J.; Vučak, M.; Krstulović, R.; Brečević, Lj.; Kralj, D. (1996). "Phase Transformation of Calcium Carbonate Polymorphs". Thermochimica Acta. 277 (1 May 1996): 175–86. Bibcode:1996TcAc..277..175P. doi:10.1016/0040-6031(95)02748-3 – via Science Direct.

- ^ Newell, Lyman C.; Maxson, R. N.; Filson, M. H. (1939). "Red Mercuric Sulfide". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 1. pp. 19–20. doi:10.1002/9780470132326.ch7. ISBN 9780470132326.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Drebushchak, V. A.; McGregor, L.; Rychkov, D. A. (February 2017). "Cooling rate "window" in the crystallization of metacetamol form II". Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. 127 (2): 1807–1814. doi:10.1007/s10973-016-5954-0. ISSN 1388-6150. S2CID 99391719.

- ^ Nyman, Jonas; Day, Graeme M. (2015). "Static and lattice vibrational energy differences between polymorphs". CrystEngComm. 17 (28): 5154–5165. doi:10.1039/C5CE00045A.

- ^ a b Dubok, Aleksandr S.; Rychkov, Denis A. (2023-04-04). "Relative Stability of Pyrazinamide Polymorphs Revisited: A Computational Study of Bending and Brittle Forms Phase Transitions in a Broad Temperature Range". Crystals. 13 (4): 617. Bibcode:2023Cryst..13..617D. doi:10.3390/cryst13040617. ISSN 2073-4352.

- ^ Borba, Ana; Albrecht, Merwe; Gómez-Zavaglia, Andrea; Suhm, Martin A.; Fausto, Rui (2010-01-14). "Low Temperature Infrared Spectroscopy Study of Pyrazinamide: From the Isolated Monomer to the Stable Low Temperature Crystalline Phase". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 114 (1): 151–161. Bibcode:2010JPCA..114..151B. doi:10.1021/jp907466h. hdl:11336/131247. ISSN 1089-5639. PMID 20055514.

- ^ a b Hoser, Anna Agnieszka; Rekis, Toms; Madsen, Anders Østergaard (2022-06-01). "Dynamics and disorder: on the stability of pyrazinamide polymorphs". Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science, Crystal Engineering and Materials. 78 (3): 416–424. Bibcode:2022AcCrB..78..416H. doi:10.1107/S2052520622004577. ISSN 2052-5206. PMC 9254588. PMID 35695115.

- ^ Smirnova, Valeriya Yu.; Iurchenkova, Anna A.; Rychkov, Denis A. (2022-08-17). "Computational Investigation of the Stability of Di-p-Tolyl Disulfide "Hidden" and "Conventional" Polymorphs at High Pressures". Crystals. 12 (8): 1157. Bibcode:2022Cryst..12.1157S. doi:10.3390/cryst12081157. ISSN 2073-4352.

- ^ Rychkov, Denis A.; Stare, Jernej; Boldyreva, Elena V. (2017). "Pressure-driven phase transition mechanisms revealed by quantum chemistry: l -serine polymorphs". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 19 (9): 6671–6676. Bibcode:2017PCCP...19.6671R. doi:10.1039/C6CP07721H. ISSN 1463-9076. PMID 28210731.

- ^ Rychkov, Denis A. (2020-01-31). "A Short Review of Current Computational Concepts for High-Pressure Phase Transition Studies in Molecular Crystals". Crystals. 10 (2): 81. Bibcode:2020Cryst..10...81R. doi:10.3390/cryst10020081. ISSN 2073-4352.

- ^ Fedorov, A. Yu.; Rychkov, D. A. (September 2020). "Comparison of Different Computational Approaches for Unveiling the High-Pressure Behavior of Organic Crystals at a Molecular Level. Case Study of Tolazamide Polymorphs". Journal of Structural Chemistry. 61 (9): 1356–1366. Bibcode:2020JStCh..61.1356F. doi:10.1134/S0022476620090024. ISSN 0022-4766. S2CID 222299340.

- ^ Rychkov, Denis A.; Arkhipov, Sergey G.; Boldyreva, Elena V. (2014-08-01). "Simple and efficient modifications of well known techniques for reliable growth of high-quality crystals of small bioorganic molecules". Journal of Applied Crystallography. 47 (4): 1435–1442. doi:10.1107/S1600576714011273. ISSN 1600-5767.

- ^ Buckley, Harold Eugene (1951). Crystal Growth. Wiley.

- ^ Surov, Artem O.; Vasilev, Nikita A.; Churakov, Andrei V.; Stroh, Julia; Emmerling, Franziska; Perlovich, German L. (2019). "Solid Forms of Ciprofloxacin Salicylate: Polymorphism, Formation Pathways and Thermodynamic Stability". Crystal Growth & Design. 19 (5): 2979–2990. Bibcode:2019CrGrD..19.2979S. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.9b00185. S2CID 132854494.

- ^ Shamshina, Julia L.; Rogers, Robin D. (2023). "Ionic Liquids: New Forms of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients with Unique, Tunable Properties". Chemical Reviews. 123 (20): 11894–11953. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00384. PMID 37797342.

- ^ "Accredited Degree Programmes" (PDF).

- ^ Bhardwaj, Rajni M. (2016), "Exploring the Physical Form Landscape of Clozapine, Amoxapine and Loxapine", Control and Prediction of Solid-State of Pharmaceuticals, Springer Theses, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 153–193, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-27555-0_7, ISBN 978-3-319-27554-3, retrieved 2023-12-20

- ^ McQuiston, Dylan K.; Mucalo, Michael R.; Saunders, Graham C. (2019-03-05). "The structure of posaconazole and its solvates with methanol, and dioxane and water: Difluorophenyl as a hydrogen bond donor". Journal of Molecular Structure. 1179: 477–486. Bibcode:2019JMoSt1179..477M. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.11.031. ISSN 0022-2860. S2CID 105578644.

- ^ Bauer J, et al. (2004). "Ritonavir: An Extraordinary Example of Conformational Polymorphism". Pharmaceutical Research. 18 (6): 859–866. doi:10.1023/A:1011052932607. PMID 11474792. S2CID 20923508.

- ^ Peddy Vishweshwar; Jennifer A. McMahon; Mark Oliveira; Matthew L. Peterson & Michael J. Zaworotko (2005). "The Predictably Elusive Form II of Aspirin". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (48): 16802–16803. Bibcode:2005JAChS.12716802V. doi:10.1021/ja056455b. PMID 16316223.

- ^ Andrew D. Bond; Roland Boese; Gautam R. Desiraju (2007). "On the Polymorphism of Aspirin: Crystalline Aspirin as Intergrowths of Two "Polymorphic" Domains". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 46 (4): 618–622. doi:10.1002/anie.200603373. PMID 17139692.

- ^ "Polytypism - Online Dictionary of Crystallography". reference.iucr.org.

- ^ Wang, In-Chun; Lee, Min-Jeong; Seo, Da-Young; Lee, Hea-Eun; Choi, Yongsun; Kim, Woo-Sik; Kim, Chang-Sam; Jeong, Myung-Yung; Choi, Guang Jin (14 June 2011). "Polymorph Transformation in Paracetamol Monitored by In-line NIR Spectroscopy During a Cooling Crystallization Process". AAPS PharmSciTech. 12 (2): 764–770. doi:10.1208/s12249-011-9642-x. PMC 3134639. PMID 21671200.

- ^ "Disappearing Polymorphs and Gastrointestinal Infringement". blakes.com. 20 July 2012. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012.

- ^ Castro, Ricardo A. E.; Maria, Teresa M. R.; Évora, António O. L.; Feiteira, Joana C.; Silva, M. Ramos; Beja, A. Matos; Canotilho, João; Eusébio, M. Ermelinda S. (2010-01-06). "A New Insight into Pyrazinamide Polymorphic Forms and their Thermodynamic Relationships". Crystal Growth & Design. 10 (1): 274–282. Bibcode:2010CrGrD..10..274C. doi:10.1021/cg900890n. ISSN 1528-7483.

- ^ Cherukuvada, Suryanarayan; Thakuria, Ranjit; Nangia, Ashwini (2010-09-01). "Pyrazinamide Polymorphs: Relative Stability and Vibrational Spectroscopy". Crystal Growth & Design. 10 (9): 3931–3941. Bibcode:2010CrGrD..10.3931C. doi:10.1021/cg1004424. ISSN 1528-7483.

- ^ "The basics of crystallography and diffraction", Christopher Hammond, Second edition, Oxford science publishers, IUCr, page 28 ISBN 0 19 8505531.

- ^ Li, Xiao; Zhu, Hongwei (2015-03-01). "Two-dimensional MoS2: Properties, preparation, and applications". Journal of Materiomics. 1 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.jmat.2015.03.003.

- ^ Wilson, J.A.; Di Salvo, F. J.; Mahajan, S. (October 1974). "Charge-density waves and superlattices in the metallic layered transition metal dichalcogenides". Advances in Physics. 50 (8): 1171–1248. doi:10.1080/00018730110102718. S2CID 218647397.

- ^ C.E. Ryan, R.C. Marshall, J.J. Hawley, I. Berman & D.P. Considine, "The Conversion of Cubic to Hexagonal Silicon Carbide as a Function of Temperature and Pressure," U.S. Air Force, Physical Sciences Research Papers, #336, Aug 1967, p 1-26.

- ^ Carletta, Andrea (2015). "Solid-State Investigation of Polymorphism and Tautomerism of Phenylthiazole-thione: A Combined Crystallographic, Calorimetric, and Theoretical Survey". Crystal Growth & Design. 15 (5): 2461–2473. Bibcode:2015CrGrD..15.2461C. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.5b00237.

- ^ Ward, Michael D. (February 2017). "Perils of Polymorphism: Size Matters". Israel Journal of Chemistry. 57 (1–2): 82–92. doi:10.1002/ijch.201600071. ISSN 0021-2148.