Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

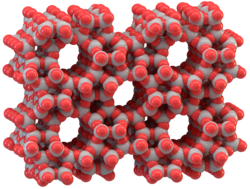

Silicate mineral

View on Wikipedia

Silicate minerals are rock-forming minerals made up of silicate groups. They are the largest and most important class of minerals and make up approximately 90 percent of Earth's crust.[1][2][3]

In mineralogy, the crystalline forms of silica (SiO2) are usually considered to be tectosilicates, and they are classified as such in the Dana system (75.1). However, the Nickel-Strunz system classifies them as oxide minerals (4.DA). Silica is found in nature as the mineral quartz and its polymorphs.

On Earth, a wide variety of silicate minerals occur in an even wider range of combinations as a result of the processes that have been forming and re-working the crust for billions of years. These processes include partial melting, crystallization, fractionation, metamorphism, weathering, and diagenesis.

Living organisms also contribute to this geologic cycle. For example, a type of plankton known as diatoms construct their exoskeletons ("frustules") from silica extracted from seawater. The frustules of dead diatoms are a major constituent of deep ocean sediment, and of diatomaceous earth.[citation needed]

General structure

[edit]A silicate mineral is generally an inorganic compound consisting of subunits with the formula [SiO2+n]2n−. Although depicted as such, the description of silicates as anions is a simplification. Balancing the charges of the silicate anions are metal cations, Mx+. Typical cations are Mg2+, Fe2+, and Na+. The Si-O-M linkage between the silicates and the metals are strong, polar-covalent bonds. Silicate anions ([SiO2+n]2n−) are invariably colorless, or when crushed to a fine powder, white. The colors of silicate minerals arise from the metal component, commonly iron.

In most silicate minerals, silicon is tetrahedral, being surrounded by four oxides. The coordination number of the oxides is variable except when it bridges two silicon centers, in which case the oxide has a coordination number of two.

Some silicon centers may be replaced by atoms of other elements, still bound to the four corner oxygen corners. If the substituted atom is not normally tetravalent, it usually contributes extra charge to the anion, which then requires extra cations. For example, in the mineral orthoclase [KAlSi

3O

8]

n, the anion is a tridimensional network of tetrahedra in which all oxygen corners are shared. If all tetrahedra had silicon centers, the anion would be just neutral silica [SiO

2]

n. Replacement of one in every four silicon atoms by an aluminum atom results in the anion [AlSi

3O−

8]

n, whose charge is neutralized by the potassium cations K+

.

Main groups

[edit]In mineralogy, silicate minerals are classified into seven major groups according to the structure of their silicate anion:[4][5]

| Major group | Structure | Chemical formula | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nesosilicates | isolated silicon tetrahedra | [SiO4]4− | olivine, garnet, zircon... |

| Sorosilicates | double tetrahedra | [Si2O7]6− | epidote, melilite group |

| Cyclosilicates | rings | [SinO3n]2n− | beryl group, tourmaline group |

| Inosilicates | single chain | [SinO3n]2n− | pyroxene group |

| Inosilicates | double chain | [Si4nO11n]6n− | amphibole group |

| Phyllosilicates | sheets | [Si2nO5n]2n− | micas and clays |

| Tectosilicates | 3D framework | [AlxSiyO(2x+2y)]x− | quartz, feldspars, zeolites |

Tectosilicates can only have additional cations if some of the silicon is replaced by an atom of lower valence such as aluminum. Al for Si substitution is common.

Nesosilicates or orthosilicates

[edit]

4. The grey ball represents the silicon atom, and the red balls are the oxygen atoms.

Nesosilicates (from Greek νῆσος nēsos 'island'), or orthosilicates, have the orthosilicate ion, present as isolated (insular) [SiO4]4− tetrahedra connected only by interstitial cations. The Nickel–Strunz classification is 09.A –examples include:

- Phenakite group

- Olivine group

- Forsterite – Mg2SiO4

- Fayalite – Fe2SiO4

- Tephroite – Mn2SiO4

- Garnet group

- Pyrope – Mg3Al2(SiO4)3

- Almandine – Fe3Al2(SiO4)3

- Spessartine – Mn3Al2(SiO4)3

- Grossular – Ca3Al2(SiO4)3

- Andradite – Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3

- Uvarovite – Ca3Cr2(SiO4)3

- Hydrogrossular – Ca

3Al

2Si

2O

8(SiO

4)

3−m(OH)

4m

- Zircon group

- Al2SiO5 group

- Andalusite – Al2SiO5

- Kyanite – Al2SiO5

- Sillimanite – Al2SiO5

- Dumortierite – Al

6.5–7BO

3(SiO

4)

3(O,OH)

3 - Topaz – Al2SiO4(F,OH)2

- Staurolite – Fe2Al9(SiO4)4(O,OH)2

- Humite group – (Mg,Fe)7(SiO4)3(F,OH)2

- Norbergite – Mg3(SiO4)(F,OH)2

- Chondrodite – Mg5(SiO4)2(F,OH)2

- Humite – Mg7(SiO4)3(F,OH)2

- Clinohumite – Mg9(SiO4)4(F,OH)2

- Datolite – CaBSiO4(OH)

- Titanite – CaTiSiO5

- Chloritoid – (Fe,Mg,Mn)2Al4Si2O10(OH)4

- Mullite (aka Porcelainite) – Al6Si2O13

Sorosilicates

[edit]

2O6−

7

Sorosilicates (from Greek σωρός sōros 'heap, mound') have isolated pyrosilicate anions Si

2O6−

7, consisting of double tetrahedra with a shared oxygen vertex—a silicon:oxygen ratio of 2:7. The Nickel–Strunz classification is 09.B. Examples include:

- Thortveitite – (Sc,Y)2(Si2O7)

- Hemimorphite (calamine) – Zn4(Si2O7)(OH)2·H2O

- Lawsonite – CaAl2(Si2O7)(OH)2·H2O

- Axinite – (Ca,Fe,Mn)3Al2(BO3)(Si4O12)(OH)

- Ilvaite – CaFeII2FeIIIO(Si2O7)(OH)

- Epidote group (has both (SiO4)4− and (Si2O7)6− groups}

- Epidote – Ca2(Al,Fe)3O(SiO4)(Si2O7)(OH)

- Zoisite – Ca2Al3O(SiO4)(Si2O7)(OH)

- Tanzanite – Ca2Al3O(SiO4)(Si2O7)(OH)

- Clinozoisite – Ca2Al3O(SiO4)(Si2O7)(OH)

- Allanite – Ca(Ce,La,Y,Ca)Al2(FeII,FeIII)O(SiO4)(Si2O7)(OH)

- Dollaseite-(Ce) – CaCeMg2AlSi3O11F(OH)

- Vesuvianite (idocrase) – Ca10(Mg,Fe)2Al4(SiO4)5(Si2O7)2(OH)4

Cyclosilicates

[edit]

Cyclosilicates (from Greek κύκλος kýklos 'circle'), or ring silicates, have three or more tetrahedra linked in a ring. The general formula is (SixO3x)2x−, where one or more silicon atoms can be replaced by other 4-coordinated atom(s). The silicon:oxygen ratio is 1:3. Double rings have the formula (Si2xO5x)2x− or a 2:5 ratio. The Nickel–Strunz classification is 09.C. Possible ring sizes include:

-

6 units [Si6O18], beryl (red: Si, blue: O)

-

3 units [Si3O9], benitoite

-

4 units [Si4O12], papagoite

-

9 units [Si9O27], eudialyte

-

12 units, double ring [Si12O30], milarite

Some example minerals are:

- 3-member single ring

- Benitoite – BaTi(Si3O9)

- 4-member single ring

- Papagoite – CaCuAlSi

2O

6(OH)

3.

- Papagoite – CaCuAlSi

- 6-member single ring

- Beryl – Be3Al2(Si6O18)

- Bazzite – Be3Sc2(Si6O18)

- Sugilite – KNa2(Fe,Mn,Al)2Li3Si12O30

- Tourmaline – (Na,Ca)(Al,Li,Mg)

3–(Al,Fe,Mn)

6(Si

6O

18)(BO

3)

3(OH)

4 - Pezzottaite – Cs(Be2Li)Al2Si6O18

- Osumilite – (K,Na)(Fe,Mg)2(Al,Fe)3(Si,Al)12O30

- Cordierite – (Mg,Fe)2Al4Si5O18

- Sekaninaite – (Fe+2,Mg)2Al4Si5O18

- 9-member single ring

- Eudialyte – Na

15Ca

6(Fe,Mn)

3Zr

3SiO(O,OH,H

2O)

3(Si

3O

9)

2(Si

9O

27)

2(OH,Cl)

2

- Eudialyte – Na

- 6-member double ring

- Milarite – K2Ca4Al2Be4(Si24O60)H2O

The ring in axinite contains two B and four Si tetrahedra and is highly distorted compared to the other 6-member ring cyclosilicates.

Inosilicates

[edit]Inosilicates (from Greek ἴς is [genitive: ἰνός inos] 'fibre'), or chain silicates, have interlocking chains of silicate tetrahedra with either SiO3, 1:3 ratio, for single chains or Si4O11, 4:11 ratio, for double chains. The Nickel–Strunz classification is 09.D – examples include:

Single chain inosilicates

[edit]- Pyroxene group

- Enstatite – orthoferrosilite series

- Enstatite – MgSiO3

- Ferrosilite – FeSiO3

- Pigeonite – Ca0.25(Mg,Fe)1.75Si2O6

- Diopside – hedenbergite series

- Diopside – CaMgSi2O6

- Hedenbergite – CaFeSi2O6

- Augite – (Ca,Na)(Mg,Fe,Al)(Si,Al)2O6

- Sodium pyroxene series

- Spodumene – LiAlSi2O6

- Pyroxferroite - (Fe,Ca)SiO3

- Enstatite – orthoferrosilite series

- Pyroxenoid group

- Wollastonite – CaSiO3

- Rhodonite – MnSiO3

- Pectolite – NaCa2(Si3O8)(OH)

Double chain inosilicates

[edit]- Amphibole group

- Anthophyllite – (Mg,Fe)7Si8O22(OH)2

- Cummingtonite series

- Cummingtonite – Fe2Mg5Si8O22(OH)2

- Grunerite – Fe7Si8O22(OH)2

- Tremolite series

- Tremolite – Ca2Mg5Si8O22(OH)2

- Actinolite – Ca2(Mg,Fe)5Si8O22(OH)2

- Hornblende – (Ca,Na)

2–3(Mg,Fe,Al)

5Si

6(Al,Si)

2O

22(OH)

2 - Sodium amphibole group

- Glaucophane – Na2Mg3Al2Si8O22(OH)2

- Riebeckite (asbestos) – Na2FeII3FeIII2Si8O22(OH)2

- Arfvedsonite – Na3(Fe,Mg)4FeSi8O22(OH)2

-

Inosilicate, pyroxene family, with 2-periodic single chain (Si2O6), diopside

-

Inosilicate, clinoamphibole, with 2-periodic double chains (Si4O11), tremolite

-

Inosilicate, unbranched 3-periodic single chain of wollastonite

-

Inosilicate with 5-periodic single chain, rhodonite

-

Inosilicate with cyclic branched 8-periodic chain, pellyite

Phyllosilicates

[edit]Phyllosilicates (from Greek φύλλον phýllon 'leaf'), or sheet silicates, form parallel sheets of silicate tetrahedra with Si2O5 or a 2:5 ratio. The Nickel–Strunz classification is 09.E. All phyllosilicate minerals are hydrated, with either water or hydroxyl groups attached. Many phyllosilicates are clay-forming and may be further classified as 1:1 clay minerals (one tetrahedral sheet and one octahedral sheet) and 2:1 clay minerals (one octahedral sheet between two tetrahedral sheets). Below is a list of the phyllosilicate mineral species that currently have articles on Wikipedia, with their chemical formulas and important varieties:

- Ajoite – (K,Na)Cu7AlSi9O24(OH)6·3H2O[6]

- Allophane – (Al2O3)(SiO2)1.3-2·2.5-3H2O[7]

- Apophyllite group[8]

- Fluorapophyllite-(K) – KCa4(Si8O22)F·8H2O

- Armstrongite – CaZr(Si6O15)·3H2O[9]

- Bannisterite – (Ca,K,Na)(Mn2+,Fe2+)10(Si,Al)16O38(OH)8·nH2O[10]

- Carletonite – KNa4Ca4Si8O18(CO3)4(OH,F)·H2O[11]

- Cavansite – Ca(VO)Si4O10·4H2O (dimorph of pentagonite)[12]

- Chapmanite – Fe3+2Sb3+(Si2O5)O3(OH)[13]

- Chlorite group[14] – (Al,Fe2+,Fe3+Li,Mg,Mn,Ni)5−6(Al,Fe3+,Si)4(O,OH)18 (2:1:1 clays)

- Chamosite – (Fe2+,Mg,Al,Fe3+)6(Si,Al)4O10(OH,O)8 (Fe endmember)

- Thuringite – (Fe,Fe,Mg,Al)6(Si,Al)4O10(O,OH)8 (Fe-rich variety of chamosite)[15]

- Clinochlore – Mg5Al(AlSi3O10)(OH)8 (Mg endmember)

- Seraphinite – variety of clinochlore with a radiating structure[16]

- Cookeite – (LiAl4◻)[AlSi3O10](OH)8

- Delessite – (Mg,Fe,Fe,Al)(Si,Al)4O10(O,OH)8[17]

- Sudoite – Mg2Al3(Si3Al)O10)(OH)8

- Chamosite – (Fe2+,Mg,Al,Fe3+)6(Si,Al)4O10(OH,O)8 (Fe endmember)

- Chrysocolla – Cu2−xAlx(H2−xSi2O5)(OH)4·nH2O, x < 1[18]

- Cymrite – BaAl2Si2(O,OH)8·H2O[19]

- Ekanite – Ca2ThSi8O20[20]

- Ganophyllite – (K,Na,Ca)2Mn8(Si,Al)12(O,OH)32·8H2O[21]

- Gyrolite – NaCa16Si23AlO60(OH)8·14H2O[22]

- Hisingerite – Fe3+2(Si2O5)(OH)4·2H2O[23]

- Imogolite – Al2SiO3(OH)4[24]

- Kampfite – Ba12(Si11Al5)O31(CO3)8Cl5[25]

- Kaolinite-Serpentine group[26]

- Greenalite – (Fe2+,Fe3+)2−3Si2O5(OH)4

- Kaolinite subgroup (1:1 clays)

- Dickite – Al2(Si2O5)(OH)4

- Kaolinite – Al2Si2O5(OH)4

- Halloysite – Al2Si2O5(OH)4

- Serpentine subgroup

- Amesite – Mg2Al(AlSiO5)(OH)4

- Antigorite – Mg3Si2O5(OH)4

- Caryopilite – Mn2+3Si2O5(OH)4

- Chrysotile – Mg3Si2O5(OH)4

- Cronstedtite – Fe2+2Fe3+((Si,Fe3+)2O5)(OH)4

- Fraipontite – (Zn,Al)3((Si,Al)2O5)(OH)4

- Lizardite – Mg3Si2O5(OH)4

- Népouite – Ni3Si2O5(OH)4

- Pecoraite – Ni3(Si2O5)(OH)4

- Kegelite – Pb8Al4(Si8O20)(SO4)2(CO3)4(OH)8[28]

- Kerolite – (Mg,Ni)3Si4O10(OH)2·nH2O[29]

- Macaulayite – (Fe,Al)24Si4O43(OH)2[30]

- Macdonaldite – BaCa4Si16O36(OH)2·10H2O[31]

- Magadiite – Na2Si14O29·11H2O[32]

- Mica group[33]

- Brittle mica group[34]

- Anandite – (Ba,K)(Fe2+,Mg)3((Si,Al,Fe)4O10)(S,OH)2

- Bityite – CaLiAl2(AlBeSi2O10)(OH)2

- Clintonite – CaAlMg2(SiAl3O10)(OH)2

- Margarite – CaAl2(Al2Si2)O10(OH)2

- Dioctahedral mica group

- Celadonite subgroup

- Aluminoceladonite – K(MgAl◻)(Si4O10)(OH)2

- Celadonite – K(MgFe3+◻)(Si4O10)(OH)2

- Glauconite – K0.60−0.85(Fe3+,Mg,Al)2(Si,Al)4O10](OH)2

- Muscovite – KAl2(AlSi3)O10(OH)2[35]

- Fuchsite – K(Al,Cr)3Si3O10(OH)2 (Cr replaces Al in muscovite)[36]

- Illite – K0.6−0.85(Al,Mg)2(Si,Al)4O10(OH)2 (K-deficient muscovite)[37] (2:1 clay)

- Mariposite – K(Al,Cr)2(Al,Si)4O10(OH)2 (Cr-bearing muscovite)[38]

- Phengite – KAl1.5(Mg,Fe)0.5(Al0.5Si3.5O10)(OH)2 (Fe/Mg-bearing muscovite)[39]

- Sericite – KAl2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2[40]

- Paragonite – NaAl2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2

- Brammallite – NaAl2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2 (Na-deficient variety of paragonite)[41]

- Roscoelite – K(V3+,Al)2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2

- Celadonite subgroup

- Trioctahedral mica group

- Aspidolite – NaMg3(AlSi3O10)(OH)2

- Biotite subgroup – K(Fe2+,Mg)2(Al,Fe3+,Mg,Ti)([Si,Al,Fe]2Si2O10)(OH,F)2

- Annite – KFe2+3(AlSi3O10)(OH)2 (Fe endmember)

- Manganophyllite – K(Fe,Mg,Mn)3AlSi3O10(OH)2 (Mn-rich variety of biotite)[42]

- Phlogopite – KMg3(AlSi3)O10(OH)2 (Mg endmember)

- Siderophyllite – KFe2+2Al(Al2Si2O10)(OH)2

- Ephesite – NaLiAl2(Al2Si2O10)(OH)2

- Hendricksite – KZn3(Si3Al)O10(OH)2

- Lepidolite (polylithionite-trilithionite series) – K(Li2,Li1.5Al1.5)AlSi3−4O10(F,OH)2

- Zinnwaldite series – KFe2+2Al(Al2Si2O10)(OH)2

- Brittle mica group[34]

- Nelenite – (Mn,Fe)16(Si12O30)(OH)14[As3+3O6(OH)3][43]

- Neptunite – KNa2Li(Fe2+)2Ti2[Si4O12]2[44]

- Okenite – Ca10Si18O46·18H2O[45]

- Palygorskite group[46] (2:1 clays)

- Palygorskite – ◻Al2Mg2◻2Si8O20(OH)2(H2O)4·4H2O

- Tuperssuatsiaite – Fe3+Fe3+2(Na◻)◻2Si8O20(OH)2(H2O)4·2H2O

- Pentagonite – Ca(VO)Si4O10·4H2O (dimorph of cavansite)[47]

- Pyrophyllite-Talc group[48]

- Minnesotaite – Fe2+3Si4O10(OH)2

- Pyrophyllite – Al2Si4O10(OH)2

- Talc – Mg3Si4O10(OH)2 (2:1 clay)

- Sanbornite – BaSi2O5[49]

- Searlesite – Na(H2BSi2O7)[50]

- Sepiolite – Mg4(Si6O15)(OH)2·6H2O[51] (2:1 clay)

- Falcondoite – (Ni,Mg)4Si6O15(OH)2·6H2O (Ni analogue of sepiolite)[52]

- Smectite group[53] (2:1 clays)

- Aliettite – Ca0.2Mg6((Si,Al)8O20)(OH)4·4H2O[54]

- Hectorite – Na0.3(Mg,Li)3(Si4O10)(F,OH)2

- Montmorillonite – (Na,Ca)0.33(Al,Mg)2(Si4O10)(OH)2·nH2O

- Nontronite – Na0.3Fe2((Si,Al)4O10)(OH)2·nH2O

- Pimelite – Ni3Si4O10(OH)2·4H2O

- Saliotite – (Li,Na)Al3(AlSi3O10)(OH)5

- Saponite – Ca0.25(Mg,Fe)3((Si,Al)4O10)(OH)2·nH2O

- Sauconite – Na0.3Zn3((Si,Al)4O10)(OH)2·4H2O

- Stevensite – (Ca,Na)xMg3−x(Si4O10)(OH)2

- Stilpnomelane group[55]

- Franklinphilite – (K,Na)4(Mn2+,Mg,Zn)48(Si,Al)72(O,OH)216·6H2O

- Stilpnomelane – (K,Ca,Na)(Fe,Mg,Al)8(Si,Al)12(O,OH)36·nH2O

- Tumchaite – Na2Zr(Si4O11)·2H2O[56]

- Ussingite – Na2AlSi3O8OH[57]

- Vermiculite – Mg0.7(Mg,Fe,Al)6(Si,Al)8O20(OH)4·8H2O[58] (2:1 clay)

- Zakharovite – Na4Mn5Si10O24(OH)6·6H2O[59]

- Zussmanite – K(Fe,Mg,Mn)13(Si,Al)18O42(OH)14[60]

-

Phyllosilicate, mica group, muscovite (red: Si, blue: O)

-

Phyllosilicate, single net of tetrahedra with 4-membered rings, apophyllite-(KF)-apophyllite-(KOH) series

-

Phyllosilicate, single tetrahedral nets of 6-membered rings, pyrosmalite-(Fe)-pyrosmalite-(Mn) series

-

Phyllosilicate, single tetrahedral nets of 6-membered rings, zeophyllite

-

Phyllosilicate, double nets with 4- and 6-membered rings, carletonite

Tectosilicates

[edit]

Tectosilicates, or "framework silicates," have a three-dimensional framework of silicate tetrahedra with SiO2 in a 1:2 ratio. This group comprises nearly 75% of the crust of the Earth.[61] Tectosilicates, with the exception of the quartz group, are aluminosilicates. The Nickel–Strunz classifications are 9.F (tectosilicates without zeolitic H2O), 9.G (tectosilicates with zeolitic H2O), and 4.DA (quartz/silica group). Below is a list of the tectosilicate mineral species that currently have articles on Wikipedia, with their chemical formulas and important varieties:

- Quartz group (silica) – SiO2

- Chalcedony – cryptocrystalline variety of silica composed mostly of quartz with some moganite

- Agate – banded variety of chalcedony

- Polymorphs of silica

- α-quartz – trigonal, "normal" quartz under 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F)

- β-quartz – hexagonal, high-temperature quartz

- Coesite – monoclinic

- Cristobalite – tetragonal

- Melanophlogite – cubic or tetragonal, rare

- Moganite – monoclinic

- Stishovite – tetragonal, extremely hard and dense

- Tridymite – orthorhombic

- Major varieties of quartz

- Amethyst – violet from Fe3+

- Citrine – yellow from Al color centers

- Prasiolite – green from Fe2+

- Smoky quartz – brown/gray from Al color centers

- Chalcedony – cryptocrystalline variety of silica composed mostly of quartz with some moganite

- Feldspar group[62]

- Alkali feldspar series (potassium feldspars or K-spar)

- Microcline – KAlSi3O8

- Amazonite – green variety of microcline

- Orthoclase – KAlSi3O8

- Moonstone – opalescent variety of orthoclase

- Anorthoclase – (Na,K)AlSi3O8

- Sanidine – KAlSi3O8

- Microcline – KAlSi3O8

- Plagioclase feldspar series

- Albite – NaAlSi3O8 (Na endmember)

- Oligoclase – (Na,Ca)Al(Si,Al)Si2O8 (Na:Ca 90:10 to 70:30)[63]

- Andesine – (Na,Ca)Al(Si,Al)Si2O8 (Na:Ca 50:50 to 70:30)[64]

- Labradorite – (Ca,Na)Al(Al,Si)Si2O8 (Na:Ca 30:70 to 50:50)[65]

- Bytownite – (Ca,Na)Al(Al,Si)Si2O8 (Na:Ca 10:90 to 30:70)[66]

- Anorthite – CaAl2Si2O8 (Ca endmember)

- Other feldspars

- Buddingtonite — NH4AlSi3O8

- Celsian – BaAl2Si2O8

- Hyalophane – (K,Ba)[Al(Si,Al)Si2O8][67]

- Rubicline – (RbAlSi3O8[68]

- Alkali feldspar series (potassium feldspars or K-spar)

- Feldspathoid group[69]

- Cancrinite subgroup

- Afghanite – (Na,K)22Ca10[Si24Al24O96](SO4)6Cl6

- Alloriite – (Na,Ca,K)26Ca4(Al6Si6O24)4(SO4)6Cl6

- Bystrite – (Na,K)7Ca(Al6Si6O24)(S5)Cl

- Cancrinite – (Na,Ca,◻)8(Al6Si6O24)(CO3,SO4)2·2H2O

- Farneseite – (Na,Ca,K)56(Al6Si6O24)7(SO4)12·6H2O

- Sacrofanite – (Na61K19Ca32)(Si84Al84O336)(SO4)26Cl2F6·2H2O

- Vishnevite – (Na,K)8(Al6Si6O24)(SO4,CO3)·2H2O

- Danalite – Be3Fe²⁺4(SiO4)3S[70]

- Kalsilite – KAlSiO4

- Leucite – K(AlSi2O6)

- Nepheline subgroup

- Davidsmithite – (Ca,◻)2Na6Al8Si8O32

- Nepheline – Na3K(Al4Si4O16)

- Sodalite subgroup

- Cancrinite subgroup

- Scapolite group[72]

- Zeolite group[73]

- Amicite – K2Na2Al4Si4O16·5H2O

- Analcime – Na(AlSi2O6)·H2O

- Brewsterite subgroup – (Ba,Sr,Ca)Al2Si6O16·5H2O

- Chabazite-Lévyne subgroup

- Clinoptilolite subgroup – (Na,Ca,K)3−6(Al6−7Si29−30O72)·20H2O

- Cowlesite – CaAl2Si3O10·6H2O

- Dachiardite-K – K4(Si20Al4O48)·13H2O

- Edingtonite – BaAl2Si3O10·4H2O

- Erionite subgroup – (Na1−2,K1−2,Ca1−2)2Al4Si14O36·15H2O

- Faujasite subgroup – (Na1−2,Ca1−2,Mg1−2)3.5[Al7Si17O48]·32H2O

- Ferrierite subgroup – [Mg2(K,Na)2Ca0.5](Si29Al7)O72·18H2O (Ferrierite-Mg)

- Garronite-Ca – Na2Ca5Al12Si20O64·27H2O

- Gismondine – CaAl2Si2O8·4H2O (Gismondine-Ca)

- Gmelinite subgroup – Na4(Si8Al4)O24·11H2O (Gmelinite-Na)

- Heulandite subgroup – (Na,Ca,K)5−6[Al8−9Si27−28O72]·nH2O

- Hsianghualite – Ca3Li2(Be3Si3O12)F2

- Laumontite – CaAl2Si4O12·4H2O

- Mordenite – (Na2,Ca,K2)4(Al8Si40)O96·28H2O

- Nabesite – Na2BeSi4O10·4H2O

- Natrolite subgroup

- Gonnardite – (Na,Ca)2(Si,Al)5O10·3H2O

- Mesolite – Na2Ca2Si9Al6O30·8H2O

- Natrolite – Na2Al2Si3O10·2H2O

- Scolecite – CaAl2Si3O10·3H2O

- Paulingite subgroup – (K2,Ca,Na2,Ba)5[Al10Si35O90]·45H2O (Paulingite-K)

- Phillipsite subgroup

- Harmotome – (Ba2(Si12Al4)O32·12H2O

- Phillipsite – (Ca3(Si10Al6)O32·12H2O (Phillipsite-Ca)

- Pollucite – (Cs,Na)2(Al2Si4O12)·2H2O

- Stilbite subgroup

- Barrerite – Na2(Si7Al2)O18·6H2O

- Stellerite – Ca4(Si28Al8)O72·28H2O

- Stilbite – (NaCa4,Na9)(Si27Al9)O72·28H2O

- Thomsonite subgroup – NaCa2Al5Si5O20·6H2O (Thomsonite-Ca)

- Wairakite – Ca(Al2Si4O12)·2H2O

- Yugawaralite – CaAl2Si6O16·4H2O

See also

[edit]- Classification of non-silicate minerals – List of IMA recognized minerals and groupings

- Classification of silicate minerals – List of IMA recognized minerals and groupings

- Silicate mineral paint – Paint coats with mineral binding agents

References

[edit]- ^ "Mineral - Silicates". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Deer, W.A.; Howie, R.A.; Zussman, J. (1992). An introduction to the rock-forming minerals (2nd ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-30094-0.

- ^ Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-47180580-7.

- ^ Deer, W.A.; Howie, R.A., & Zussman, J. (1992). An introduction to the rock forming minerals (2nd edition ed.). London: Longman ISBN 0-582-30094-0

- ^ Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis ||1985). Manual of Mineralogy, Wiley, (20th edition ed.). ISBN 0-471-80580-7

- ^ "Ajoite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Allophane". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Apophyllite Group". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Armstrongite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Bannisterite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Carletonite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Cavansite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Chapmanite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "Chlorite Group". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- ^ "Thuringite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Seraphinite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Delessite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "Chrysocolla". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ "Cymrite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "Ekanite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "Ganophyllite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "Gyrolite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "Hisingerite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "Imogolite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Kampfite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Kaolinite-Serpentine Group". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Bowenite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Kegelite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Kerolite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Macaulayite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Macdonaldite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Magadiite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Mica Group". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 February 2025.

- ^ "Brittle Mica". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 February 2025.

- ^ "Muscovite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 February 2025.

- ^ "Fuchsite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 February 2025.

- ^ "Illite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 February 2025.

- ^ "Mariposite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 February 2025.

- ^ "Phengite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ "Sericite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Brammallite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Manganophyllite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Nelenite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Neptunite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Okenite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Palygorskite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- ^ "Pentagonite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Pyrophyllite-Talc Group". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 26 June 2025.

- ^ "Sanbornite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Searlesite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Sepiolite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- ^ "Falcondoite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "Smectite Group". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Aliettite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Stilpnomelane Group". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "Tumchaite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Ussingite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Vermiculite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- ^ "Zakharovite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ "Zussmanite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ Deer, W.A.; Howie, R.A.; Wise, W.S.; Zussman, J. (2004). Rock-forming minerals. Volume 4B. Framework silicates: silica minerals. Feldspathoids and the zeolites (2nd ed.). London: Geological Society of London. p. 982 pp.

- ^ "Feldspar Group". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Oligoclase". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Andesine". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Labradorite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Bytownite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Hyalophane". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Rubicline". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Feldspathoid". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Danalite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Tugtupite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Scapolite". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Zeolite Group". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 22 February 2025.

External links

[edit]Silicate mineral

View on Grokipedia- Nesosilicates (island silicates) with isolated tetrahedra, e.g., olivine and garnet.

- Sorosilicates (double tetrahedra), e.g., epidote.

- Cyclosilicates (ring structures), e.g., beryl and tourmaline.

- Inosilicates (chain silicates), including single-chain pyroxenes and double-chain amphiboles.

- Phyllosilicates (sheet silicates), e.g., micas, chlorite, and clay minerals.

- Tectosilicates (framework silicates), e.g., quartz, feldspars, and zeolites.

This classification highlights the versatility of silicate bonding, which allows for the incorporation of elements like aluminum, iron, magnesium, and alkali metals, influencing mineral properties such as hardness, cleavage, and color. Geologically, silicates drive processes like weathering, volcanism, and plate tectonics, forming the foundation of the rock cycle and serving as key indicators of Earth's thermal and chemical history.[6][7][1][3]

![6 units [Si6O18], beryl (red: Si, blue: O)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5a/Beryll.ring.combined.png/120px-Beryll.ring.combined.png)

![3 units [Si3O9], benitoite](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Benitoid.2200.png/120px-Benitoid.2200.png)

![4 units [Si4O12], papagoite](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Papagoite.2200.png/120px-Papagoite.2200.png)

![9 units [Si9O27], eudialyte](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Eudialyte.2200.png/120px-Eudialyte.2200.png)

![12 units, double ring [Si12O30], milarite](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Milarite.png/120px-Milarite.png)