Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

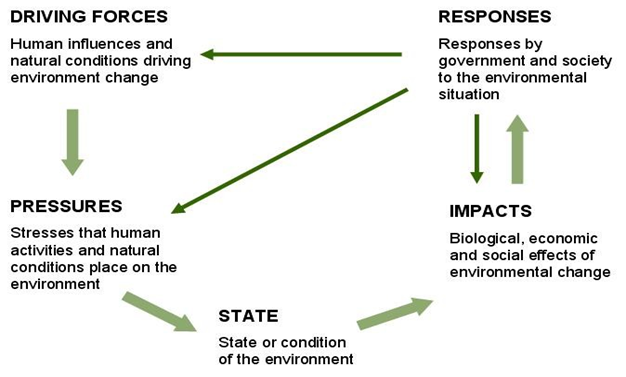

DPSIR

View on WikipediaDPSIR (drivers, pressures, state, impact, and response model of intervention) is a causal framework used to describe the interactions between society and the environment.[1] It seeks to analyze and assess environmental problems by bringing together various scientific disciplines, environmental managers, and stakeholders, and solve them by incorporating sustainable development. First, the indicators are categorized into "drivers" which put "pressures" in the "state" of the system, which in turn results in certain "impacts" that will lead to various "responses" to maintain or recover the system under consideration.[2] It is followed by the organization of available data, and suggestion of procedures to collect missing data for future analysis.[3] Since its formulation in the late 1990s, it has been widely adopted by international organizations for ecosystem-based study in various fields like biodiversity, soil erosion, and groundwater depletion and contamination. In recent times, the framework has been used in combination with other analytical methods and models, to compensate for its shortcomings. It is employed to evaluate environmental changes in ecosystems, identify the social and economic pressures on a system, predict potential challenges and improve management practices.[4] The flexibility and general applicability of the framework make it a resilient tool that can be applied in social, economic, and institutional domains as well.[3]

History

[edit]The Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response framework was developed by the European Environment Agency (EEA) in 1999. It was built upon several existing environmental reporting frameworks, like the Pressure-State-Response (PSR) framework developed by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1993, which itself was an extension of Rapport and Friend's Stress-Response (SR) framework (1979). The PSR framework simplified environmental problems and solutions into variables that stress the cause-effect relationship between human activities that exert pressure on the environment, the state of the environment, and society's response to the condition. Since it focused on anthropocentric pressures and responses, it did not effectively factor natural variability into the pressure category. This led to the development of the expanded Driving Force-State-Response (DSR) framework, by the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) in 1997. A primary modification was the expansion of the concept of "pressure" to include social, political, economic, demographic, and natural system pressures. However, by replacing "pressure" with "driving force", the model failed to account for the underlying reasons for the pressure, much like its antecedent. It also did not address the motivations behind responses to changes in the state of the environment. The refined DPSIR model sought to address these shortcomings of its predecessors by addressing root causes of the human activities that impact the environment, by incorporating natural variability as a pressure on the current state and addressing responses to the impact of changes in state on human well-being. Unlike PSR and DSR, DPSIR is not a model, but a means of classifying and disseminating information related to environmental challenges.[5] Since its conception, it has evolved into modified frameworks like Driver-Pressure-Chemical State-Ecological State-Response (DPCER),[6] Driver-Pressure-State-Welfare-Response (DPSWR),[7] and Driver-Pressure-State-Ecosystem-Response (DPSER).[8][9]

The DPSIR Framework

[edit]Driver (Driving Force)

[edit]Driver refers to the social, demographic, and economic developments which influence the human activities that have a direct impact on the environment.[3] They can further be subdivided into primary and secondary driving forces. Primary driving forces refer to technological and societal actors that motivate human activities like population growth and distribution of wealth. The developments induced by these drivers give rise to secondary driving forces, which are human activities triggering "pressures" and "impacts", like land-use changes, urban expansion and industrial developments. Drivers can also be identified as underlying or immediate, physical or socio-economic, and natural or anthropogenic, based on the scope and sector in which they are being used.[1]

Pressure

[edit]Pressure represents the consequence of the driving force, which in turn affects the state of the environment. They are usually depicted as unwanted and negative, based on the concept that any change in the environment caused by human activities is damaging and degrading.[3] Pressures can have effects on the short run (e.g.: deforestation), or the long run (e.g.: climate change), which if known with sufficient certainty, can be expressed as a probability. They can be both human-induced, like emissions, fuel extraction, and solid waste generation, and natural processes, like solar radiation and volcanic eruptions.[1] Pressures can also be sub-categorized as endogenic managed pressures, when they stem from within the system and can be controlled (e.g.: land claim, power generation), and as exogenic unmanaged pressures, when they stem from outside the system and cannot be controlled (e.g.: climate change, geomorphic activities).[9]

State

[edit]State describes the physical, chemical and biological condition of the environment or observable temporal changes in the system. It may refer to natural systems (e.g.: atmospheric CO2 concentrations, temperature), socio-economic systems (e.g.: living conditions of humans, economic situations of an industry), or a combination of both (e.g.: number of tourists, size of current population).[3] It includes a wide range of features, like physico-chemical characteristics of ecosystems, quantity and quality of resources or "carrying capacity", management of fragile species and ecosystems, living conditions for humans, and exposure or the effects of pressures on humans. It is not intended to just be static, but to reflect current trends as well, like increasing eutrophication and change in biodiversity.[9]

Impact

[edit]Impact refers to how changes in the state of the system affect human well-being. It is often measured in terms of damages to the environment or human health, like migration, poverty, and increased vulnerability to diseases,[3] but can also be identified and quantified without any positive or negative connotation, by simply indicating a change in the environmental parameters.[9] Impact can be ecologic (e.g.: reduction of wetlands, biodiversity loss), socio-economic (e.g.: reduced tourism), or a combination of both.[3] Its definition may vary depending on the discipline and methodology applied. For instance, it refers to the effect on living beings and non-living domains of ecosystems in biosciences (e.g.: modifications in the chemical composition of air or water), whereas it is associated with the effects on human systems related to changes in the environmental functions in socio-economic sciences (e.g.: physical and mental health).[9]

Response

[edit]Response refers to actions taken to correct the problems of the previous stages, by adjusting the drivers, reducing the pressure on the system, bringing the system back to its initial state, and mitigating the impacts. It can be associated uniquely with policy action, or to different levels of the society, including groups and/or individuals from the private, government or non-governmental sectors. Responses are mostly designed and/or implemented as political actions of protection, mitigation, conservation, or promotion. A mix of effective top-down political action and bottom-up social awareness can also be developed as responses, such as eco-communities or improved waste recycling rates.[9]

Criticisms and Limitations

[edit]Despite the adaptability of the framework, it has faced several criticisms. One of the main goals of the framework is to provide environmental managers, scientists of various disciplines, and stakeholders with a common forum and language to identify, analyze and assess environmental problems and consequences.[3] However, several notable authors have mentioned that it lacks a well-defined set of categories, which undermines the comparability between studies, even if they are similar.[10] For instance, climate change can be considered as a natural driver, but is primarily caused by greenhouse gases (GSG) produced by human activities, which may be categorized under "pressure". A wastewater treatment plant is considered a response while dealing with water pollution, but a pressure when effluent runoff leading to eutrophication is taken into account. This ambivalence of variables associated with the framework has been criticized as a lack of good communication between researchers and between stakeholders and policymakers.[11] Another criticism is the misguiding simplicity of the framework, which ignores the complex synergy between the categories. For instance, an impact can be caused by various different state conditions and responses to other impacts, which is not addressed by DPSIR.[1][9] Some authors also argue that the framework is flawed as it does not clearly illustrate the cause-effect linkage for environmental problems.[12] The reasons behind these contextual differences seem to be differences in opinions, characteristics of specific case studies, misunderstanding of the concepts and inadequate knowledge of the system under consideration.[11]

DPSIR was initially proposed as a conceptual framework rather than a practical guidance, by global organizations. This means that at a local level, analyses using the framework can cause some significant problems. DPSIR does not encourage the examination of locally specific attributes for individual decisions, which when aggregated, could have potentially large impacts on sustainability. For instance, a farmer who chooses a particular way of livelihood may not create any consequential alterations on the system, but the aggregation of farmers making similar choices will have a measurable and tangible effect. Any efforts to evaluate sustainability without considering local knowledge could lead to misrepresentations of local situations, misunderstandings of what works in particular areas and even project failure.[11]

While there is no explicit hierarchy of authority in the DPSIR framework, the power difference between "developers" and the "developing" could be perceived as the contributor to the lack of focus on local, informal responses at the scale of drivers and pressures, thus compromising the validity of any analysis conducted using it. The "developers" refer to the Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), State mechanisms and other international organizations with the privilege to access various resources and power to use knowledge to change the world, and the "developing" refers to local communities. According to this criticism, the latter is less capable of responding to environmental problems than the former. This undermines valuable indigenous knowledge about various components of the framework in a particular region, since the inclusion of the knowledge is almost exclusively left at the discretion of the "developers".[11]

Another limitation of the framework is the exclusion of social and economic developments on the environment, particularly for future scenarios. Furthermore, DPSIR does not explicitly prioritize responses and fails to determine the effectiveness of each response individually, when working with complex systems. This has been one of the most criticized drawbacks of the framework, since it fails to capture the dynamic nature of real-world problems, which cannot be expressed by simple causal relations.[4]

Applications

[edit]Despite its criticisms, DPSIR continues to be widely used to frame and assess environmental problems to identify appropriate responses. Its main objective is to support sustainable management of natural resources. DPSIR structures indicators related to the environmental problem addressed with reference to the political objectives and focuses on supposed causal relationships effectively, such that it appeals to policy actors. Some examples include the assessment of the pressure of alien species,[13] evaluation of impacts of developmental activities on the coastal environment and society,[14] identification of economic elements affecting global wildfire activities,[15] and cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and gross domestic product (GDP) correction.[16]

To compensate for its shortcomings, DPSIR is also used in conjunction with several analytical methods and models. It has been used in conjunction with Multiple-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) for desertification risk management,[17] with Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to study urban green electricity power,[18] and with Tobit model to assess freshwater ecosystems.[19] The framework itself has also been modified to assess specific systems, like DPSWR, which focuses on the impacts on human welfare alone, by shifting ecological impact to the state category.[10] Another approach is a differential DPSIR (ΔDPSIR), which evaluates the changes in drivers, pressures and state after implementing a management response, making it valuable both as a scientific output and a system management tool.[20] The flexibility offered by the framework makes it an effective tool with numerous applications, provided the system is properly studied and understood by the stakeholders.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Maxim, Laura; Spangenberg, Joachim H.; O'Connor, Martin (November 2009). "An analysis of risks for biodiversity under the DPSIR framework". Ecological Economics. 69 (1): 12–23. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.03.017.

- ^ Ness, Barry; Anderberg, Stefan; Olsson, Lennart (2010-05-01). "Structuring problems in sustainability science: The multi-level DPSIR framework". Geoforum. 41 (3): 479–488. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.12.005. ISSN 0016-7185.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Martins, Joana H.; Camanho, Ana S.; Gaspar, Miguel B. (December 2012). "A review of the application of driving forces – Pressure – State – Impact – Response framework to fisheries management". Ocean & Coastal Management. 69: 273–281. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.07.029.

- ^ a b Malmir, Mahsa; Javadi, Saman; Moridi, Ali; Neshat, Aminreza; Razdar, Babak (July 2021). "A new combined framework for sustainable development using the DPSIR approach and numerical modeling". Geoscience Frontiers. 12 (4) 101169. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2021.101169. S2CID 233543312.

- ^ Bowen, Robert E.; Riley, Cory (2003-01-01). "Socio-economic indicators and integrated coastal management". Ocean & Coastal Management. The Role of Indicators in Integrated Coastal Management. 46 (3): 299–312. doi:10.1016/S0964-5691(03)00008-5. ISSN 0964-5691.

- ^ Rekolainen, Seppo; Kämäri, Juha; Hiltunen, Marjukka; Saloranta, Tuomo M. (December 2003). "A conceptual framework for identifying the need and role of models in the implementation of the water framework directive". International Journal of River Basin Management. 1 (4): 347–352. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.122.5939. doi:10.1080/15715124.2003.9635217. ISSN 1571-5124. S2CID 989048.

- ^ O'Higgins, Tim; Farmer, Andrew; Daskalov, Georgi; Knudsen, Stale; Mee, Laurence (2014-09-26). "Achieving good environmental status in the Black Sea: scale mismatches in environmental management". Ecology and Society. 19 (3). doi:10.5751/ES-06707-190354. hdl:10468/2417. ISSN 1708-3087.

- ^ Kelble, Christopher R.; Loomis, Dave K.; Lovelace, Susan; Nuttle, William K.; Ortner, Peter B.; Fletcher, Pamela; Cook, Geoffrey S.; Lorenz, Jerry J.; Boyer, Joseph N. (2013-08-12). "The EBM-DPSER Conceptual Model: Integrating Ecosystem Services into the DPSIR Framework". PLOS ONE. 8 (8) e70766. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...870766K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070766. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3741316. PMID 23951002.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gari, Sirak Robele; Newton, Alice; Icely, John D. (January 2015). "A review of the application and evolution of the DPSIR framework with an emphasis on coastal social-ecological systems". Ocean & Coastal Management. 103: 63–77. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.11.013.

- ^ a b Cooper, Philip (October 2013). "Socio-ecological accounting: DPSWR, a modified DPSIR framework, and its application to marine ecosystems" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 94: 106–115. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.07.010. ISSN 0921-8009. S2CID 153432235.

- ^ a b c d Carr, Edward R.; Wingard, Philip M.; Yorty, Sara C.; Thompson, Mary C.; Jensen, Natalie K.; Roberson, Justin (December 2007). "Applying DPSIR to sustainable development". International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology. 14 (6): 543–555. doi:10.1080/13504500709469753. ISSN 1350-4509. S2CID 16526139.

- ^ Rekolainen, Seppo; Kämäri, Juha; Hiltunen, Marjukka; Saloranta, Tuomo M. (December 2003). "A conceptual framework for identifying the need and role of models in the implementation of the water framework directive". International Journal of River Basin Management. 1 (4): 347–352. doi:10.1080/15715124.2003.9635217. ISSN 1571-5124. S2CID 989048.

- ^ Dai, Xiao Peng; Li, Dong Hui (September 2013). "Research on Risk Assessment of Alien Species Based on Group AHP". Advanced Materials Research. 765–767: 3094–3098. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.765-767.3094. ISSN 1662-8985. S2CID 136828520.

- ^ Lin, Tao; Xue, Xiong-Zhi; Lu, Chang-Yi (2007-03-16). "Analysis of Coastal Wetland Changes Using the "DPSIR" Model: A Case Study in Xiamen, China". Coastal Management. 35 (2–3): 289–303. doi:10.1080/08920750601169592. ISSN 0892-0753. S2CID 86862004.

- ^ Kim, Yeon-Su; Rodrigues, Marcos; Robinne, François-Nicolas (October 2021). "Economic drivers of global fire activity: A critical review using the DPSIR framework". Forest Policy and Economics. 131 102563. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102563.

- ^ Bidone, E. D.; Lacerda, L. D. (2004-03-01). "The use of DPSIR framework to evaluate sustainability in coastal areas. Case study: Guanabara Bay basin, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil" (PDF). Regional Environmental Change. 4 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1007/s10113-003-0059-2. ISSN 1436-378X. S2CID 153371987.

- ^ Akbari, Morteza; Memarian, Hadi; Neamatollahi, Ehsan; Jafari Shalamzari, Masoud; Alizadeh Noughani, Mohammad; Zakeri, Dawood (2021-02-01). "Prioritizing policies and strategies for desertification risk management using MCDM–DPSIR approach in northeastern Iran". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 23 (2): 2503–2523. doi:10.1007/s10668-020-00684-3. ISSN 1573-2975. S2CID 213169550.

- ^ Cheng, Chao; Zhou, Yu-Hui; Yue, Kai-Wei; Yang, Jian; He, Zhan-Yong; Liang, Na (2011). "Study of SEA Indicators System of Urban Green Electricity Power Based on Fuzzy AHP and DPSIR Model". Energy Procedia. 12: 155–162. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2011.10.022.

- ^ Kosamu, Ishmael Bobby Mphangwe; Makwinja, Rodgers; Kaonga, Chikumbusko Chiziwa; Mengistou, Seyoum; Kaunda, Emmanuel; Alamirew, Tena; Njaya, Friday (January 2022). "Application of DPSIR and Tobit Models in Assessing Freshwater Ecosystems: The Case of Lake Malombe, Malawi". Water. 14 (4): 619. doi:10.3390/w14040619. ISSN 2073-4441.

- ^ Nobre, Ana M. (2009-07-01). "An Ecological and Economic Assessment Methodology for Coastal Ecosystem Management". Environmental Management. 44 (1): 185–204. Bibcode:2009EnMan..44..185N. doi:10.1007/s00267-009-9291-y. ISSN 1432-1009. PMID 19471999. S2CID 39378116.

External links

[edit]DPSIR

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Evolution

Precursor Frameworks

The Stress-Response (SR) framework emerged in 1979, developed by statisticians Tony Friend and David Rapport at Statistics Canada as a foundational approach to environmental statistics.[4] It conceptualized environmental degradation through "stresses"—human-induced alterations to ecosystems—and "responses," encompassing both ecological feedbacks and human interventions like policy measures.[5] This model emphasized causality between anthropogenic stressors and environmental changes, providing an early structure for tracking ecosystem health in regions like the Laurentian Great Lakes basin, but it lacked explicit integration of socioeconomic drivers or welfare impacts.[6] Building directly on the SR model, the Pressure-State-Response (PSR) framework was formalized by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in the early 1990s, specifically through its 1993 Core Set of Indicators for Environmental Performance Reviews.179/en/pdf) PSR refined the causal chain by distinguishing "pressures" (direct human activities such as emissions or resource extraction) from the "state" of the environment (measurable conditions like air quality or biodiversity levels), with "responses" capturing policy and societal actions to mitigate pressures.[7] Adopted for international environmental reporting, PSR enabled structured indicator sets for performance assessments across OECD member countries, addressing limitations in SR by incorporating quantifiable pressures but still omitting upstream socioeconomic forces and downstream human-centric consequences.[8] These frameworks laid the groundwork for DPSIR by establishing a linear causal paradigm for human-environment interactions, influencing subsequent adaptations in global environmental agencies. The transition from SR to PSR highlighted the need for policy-relevant indicators, while both underscored empirical causality over normative assumptions, prioritizing data on observable pressures and states derived from national statistics and monitoring programs.[3]Development of DPSIR

The DPSIR framework emerged in the late 1990s through the efforts of the European Environment Agency (EEA) to enhance environmental reporting and policy analysis across Europe. Building directly on the OECD's Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model, the EEA introduced "Drivers" to capture underlying socio-economic forces initiating environmental changes and "Impacts" to explicitly link environmental degradation to effects on human health, ecosystems, and welfare. This expansion aimed to provide a more complete causal chain for structuring indicators and assessing policy effectiveness in reports like the EEA's State of the Environment assessments. The framework was first systematically outlined in the EEA's 1999 technical report, Environmental Indicators: Typology and Overview, which proposed DPSIR as a typology for classifying environmental data to support decision-making. This document emphasized DPSIR's role in integrating diverse indicators—ranging from economic drivers like population growth and consumption patterns to responsive measures such as regulations and technological innovations—into a unified analytical structure. The development process involved collaboration among EEA experts, drawing on pilot applications in sectoral reports, such as transport and environment linkages, to refine the model's applicability for multi-scale environmental problems.[9] Subsequent refinements in the early 2000s focused on operationalizing DPSIR for practical use, including its adaptation for integrated environmental assessments and indicator sets under the European Union's environmental action programs. For instance, the EEA's 2003 report on Europe's environment incorporated DPSIR to evaluate progress toward sustainable development goals, highlighting its utility in identifying feedback loops between human activities and ecological states. Despite its institutional origins within the EEA, the framework's development reflected broader international influences, including input from OECD and UNEP indicator systems, though EEA documentation underscores its tailored evolution for European policy contexts.[3]Key Milestones and Institutional Adoption

The Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model, a precursor to DPSIR, was formalized by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1993 to structure environmental reporting by linking human activities to ecological conditions and policy responses.[1] This framework built on earlier stress-response approaches dating to 1979, emphasizing causal chains in environmental degradation.[3] The DPSIR framework emerged in 1999 when the European Environment Agency (EEA) expanded PSR by explicitly adding "Drivers" (societal forces like economic activities) and "Impacts" (effects on human welfare and ecosystems), creating a more comprehensive causal model for policy analysis and indicator development.[1] [10] This adaptation was detailed in EEA's early reporting mechanisms, such as those introduced in Europe's Environment assessments around 1998–1999, where DPSIR criteria guided indicator selection for integrated environmental evaluation.[11] A subsequent milestone occurred in 2012 with the United Nations Environment Programme's (UNEP) adoption of DPSIR in its Mediterranean Marine and Coastal Environment report, applying it to regional assessments of pollution and biodiversity loss.[1] Institutionally, DPSIR gained traction through the EEA, which integrated it as a core tool for annual environmental signaling and thematic reports starting in the late 1990s, influencing EU-wide policy under directives like the Water Framework Directive.[12] [13] The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) incorporated a PSR/DPSIR variant in 1994 for risk assessments, while UNEP and the EU's marine projects (e.g., DEVOTES and ELME in the 2000s–2010s) extended its use to global and coastal management, with over 152 peer-reviewed studies and 27 funded projects documenting applications by 2016.[1] This adoption reflects DPSIR's role in bridging science and decision-making, though critiques note its linear assumptions limit handling of complex feedbacks in adaptive governance.[1]Core Components of the Framework

Drivers

In the DPSIR framework, drivers, also termed driving forces, constitute the foundational social, economic, demographic, technological, and cultural processes that propel human activities and generate pressures on environmental systems. These elements initiate the causal chain by reflecting broader societal dynamics, such as the pursuit of economic growth or fulfillment of basic needs, which indirectly influence natural resources and ecosystems.[13][14] Drivers are often categorized into primary and secondary types. Primary drivers encompass inherent societal imperatives like the demand for food, shelter, water, employment, and wealth accumulation, alongside macro-level factors including population expansion and technological progress. Secondary drivers emerge as derivatives, such as heightened requirements for transportation, recreation, or housing, which stem from primary forces and manifest in specific sectoral activities. For example, population growth in Europe has driven increased urbanization rates, with urban population rising from 68.6% in 1990 to 75.3% in 2020, amplifying land use demands.[15][16] Empirical applications highlight drivers like economic development and lifestyle shifts. In agricultural contexts, rising global food demand, projected to increase by 50% by 2050 due to population growth to 9.7 billion, serves as a key driver leading to intensified farming practices. Similarly, in energy sectors, gross domestic product (GDP) growth correlates with higher consumption; European final energy use rose alongside GDP expansion post-2008 recovery, underscoring economic drivers' role. These are quantified through indicators such as GDP per capita, which in the EU averaged €35,000 in 2022, and consumption patterns tracked via material footprint metrics.[17][9] The analysis of drivers emphasizes their dynamic nature, influenced by policy, innovation, and global events. For instance, technological advancements in renewable energy have begun mitigating traditional fossil fuel dependency drivers, though challenges persist from emerging economies' industrialization. This component's focus on root causes enables targeted responses, distinguishing transient pressures from enduring systemic forces.[18]Pressures

Pressures in the DPSIR framework denote the direct biophysical stresses imposed on environmental systems by human activities, serving as the intermediary link between broader driving forces—such as economic sectors or consumption patterns—and observable changes in environmental conditions. These pressures manifest as tangible outputs from societal actions, including pollutant emissions, resource depletion, and physical alterations to ecosystems, which collectively strain natural capacities without immediate feedback loops to drivers. The concept originated in adaptations of earlier models by organizations like the OECD and was formalized by the European Environment Agency (EEA) in the mid-1990s to facilitate structured environmental assessments.[19][15] Common categories of pressures include atmospheric, aquatic, and terrestrial stressors. Atmospheric pressures encompass greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., 36.8 billion metric tons of CO2-equivalent globally in 2022 from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes) and air pollutants like nitrogen oxides from transportation. Aquatic pressures involve nutrient loading from agriculture, with Europe's rivers receiving over 1.5 million tons of nitrogen annually via runoff, alongside wastewater discharges contributing to eutrophication. Terrestrial pressures feature land conversion for agriculture and urban expansion, which fragmented 75% of global temperate forests by 2000, alongside resource extraction such as 92 billion tons of biomass, fossil fuels, and metal ores harvested worldwide in 2017.[20][21][22] Indicators for monitoring pressures emphasize measurable proxies to quantify these stresses, enabling causal tracing to drivers. Examples include energy intensity metrics (e.g., kilograms of oil equivalent per unit of GDP), waste generation rates (e.g., 2.01 billion tons of municipal solid waste globally in 2016), and fishery extraction volumes (e.g., 96 million tons of wild-caught fish annually as of recent FAO data). These indicators, often derived from national statistics and satellite monitoring, highlight pressures' scalability across local to global levels, though data gaps persist in underreported sectors like informal mining. The EEA's typology classifies pressure indicators as those capturing "emissions, waste, and resource use," underscoring their role in predicting state degradation without conflating them with socioeconomic drivers.[19][23][24]State

The State component of the DPSIR framework refers to the observable condition of the environment, capturing its physical, chemical, biological, and sometimes socio-economic attributes as altered by human-induced pressures. This stage quantifies how environmental systems have changed, providing a baseline for evaluating degradation or improvement through measurable indicators such as pollutant concentrations, habitat extent, species populations, and ecosystem functionality.[25][26] State indicators serve as diagnostic tools to link pressures to tangible environmental outcomes, often derived from empirical monitoring data to assess compliance with regulatory thresholds. For instance, in aquatic ecosystems, state is commonly measured by parameters like dissolved oxygen levels (typically below 5 mg/L indicating hypoxia), nutrient concentrations (e.g., nitrate exceeding 50 mg/L in groundwater), and biological metrics such as the Ecological Quality Ratio under the EU Water Framework Directive, which scored only 40% of European surface waters as achieving good status in 2018 assessments.[18][1] In terrestrial contexts, state encompasses soil organic carbon content (global averages declining by 0.6% annually in croplands from 1960-2010) and vegetation cover indices from satellite data like NDVI, reflecting pressures from land conversion.[27] The measurement of state relies on standardized protocols to ensure comparability, such as those from the European Environment Agency's indicator database, which tracks air quality via annual mean PM2.5 concentrations (EU average 12.7 μg/m³ in 2022, exceeding WHO guidelines of 5 μg/m³). Challenges in state assessment include data gaps in under-monitored regions and the lag between pressures and detectable changes, necessitating long-term series for causal inference; for example, ocean acidification state, measured by pH declines of 0.1 units since pre-industrial times, stems from cumulative CO2 absorption but requires decadal observations for precision.[11][28] These indicators inform whether environmental states cross tipping points, such as biodiversity loss rates exceeding natural background by 100-1000 times in recent decades per IPBES assessments integrated into DPSIR analyses.[29]Impacts

In the DPSIR framework, impacts represent the direct and indirect consequences of alterations in the environmental state on human health, ecosystems, biodiversity, welfare, and economic productivity.[13] These effects arise from the degradation or transformation of environmental conditions driven by upstream pressures, such as pollution-induced respiratory illnesses from elevated particulate matter levels or habitat fragmentation leading to species population declines.[23] For instance, in assessments of air quality, impacts include an estimated 400,000 premature deaths annually in Europe attributable to fine particulate matter exposure exceeding WHO guidelines, as quantified through exposure-response functions in epidemiological studies.[19] Impacts are typically evaluated using indicators that capture both biophysical and socioeconomic dimensions, such as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost due to environmental hazards or monetary valuations of ecosystem service losses from biodiversity decline.[30] In marine contexts, state changes like ocean acidification from CO2 absorption result in impacts including reduced shellfish calcification rates, which disrupt fisheries yielding economic losses exceeding €1 billion yearly in affected regions, based on bioeconomic models integrating calcification data and market values.[1] Similarly, land-use pressures altering soil state can manifest as impacts on agricultural yields, with erosion reducing global crop productivity by up to 0.3% annually, compounded by nutrient depletion effects documented in long-term field trials.[31] Quantifying impacts requires causal attribution, often challenged by confounding factors like synergistic stressors, yet frameworks employ integrated modeling to link state metrics (e.g., water quality indices) to endpoint outcomes, such as eutrophication-driven algal blooms correlating with fish kill events and tourism revenue drops of 20-50% in coastal areas.[28] Peer-reviewed applications highlight human-centered impacts, including livelihood disruptions from resource scarcity, where, for example, mangrove degradation has led to heightened vulnerability for 15 million coastal dwellers through lost storm protection services valued at $500-1,000 per hectare annually.[32] Ecosystem-focused impacts emphasize functional losses, like diminished pollination services from pollinator declines, reducing fruit set by 3-5% in crops and incurring global costs of $235-577 billion yearly, derived from yield gap analyses.[33] The framework underscores that impacts are not merely endpoints but feedback triggers for responses, with empirical evidence from case studies showing delayed realizations, such as climate-induced state shifts manifesting in biodiversity impacts decades after initial pressures, necessitating time-lagged indicators for accurate assessment.[28] In river basin evaluations, impacts from hydrological alterations include reduced water availability affecting 2.4 billion people globally, with socioeconomic costs including GDP losses of 0.5-1% in water-stressed economies, supported by integrated hydrological-economic simulations.[34] Overall, impacts in DPSIR facilitate prioritization of interventions by revealing the human and ecological toll of unmitigated state changes, grounded in verifiable indicator sets from agencies like the EEA.[24]Responses

In the DPSIR framework, responses denote the deliberate actions, policies, and societal measures implemented to counteract environmental degradation, targeting upstream elements like drivers or pressures, or downstream aspects such as state changes and impacts. These interventions form a feedback mechanism, enabling policymakers to adapt strategies based on observed outcomes, with the goal of restoring or enhancing environmental quality. Developed as part of the European Environment Agency's (EEA) integrated reporting approach, responses emphasize proactive governance, including regulatory enforcement, economic incentives, and technological innovations.[13][35] Responses can be categorized into institutional, technical, and behavioral types. Institutional responses involve legal and policy frameworks, such as emission standards under the European Union's Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC), which mandate member states to achieve good ecological status in water bodies by reducing pollution pressures. Technical responses encompass innovations like wastewater treatment upgrades or renewable energy adoption to alleviate resource depletion. Behavioral responses promote shifts in consumption patterns, often through public education or market-based tools like carbon pricing, as seen in the EU Emissions Trading System established in 2005, which has reduced greenhouse gas emissions by incentivizing lower-carbon production.[15] The effectiveness of responses is evaluated via dedicated indicators, which track implementation and outcomes rather than mere intent. EEA response indicators include metrics on policy adoption rates, such as the proportion of industrial facilities complying with integrated pollution prevention and control directives, or investment levels in sustainable infrastructure, reported annually since the framework's formalization in 1999. These indicators facilitate iterative assessment, revealing gaps like delayed response to emerging pressures from urbanization, where only 25% of EU urban areas met air quality standards in 2022 despite targeted measures. Empirical evidence from applications, such as river basin management under the DPSIR model, shows that combined responses—e.g., regulatory caps and restoration projects—have improved water quality states in 40% of monitored European catchments since 2010.[35][36] Challenges in response formulation arise from causal complexities, where single interventions may insufficiently address interconnected drivers; for instance, agricultural subsidy reforms in the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (updated 2023) aim to curb fertilizer pressures but require complementary monitoring to avoid unintended impacts on food security. Nonetheless, the framework's strength lies in its promotion of evidence-based responses, prioritizing those with verifiable causal links to improved states, as demonstrated in EEA assessments linking policy responses to a 15% decline in acid rain impacts across Europe from 1990 to 2020.[9][15]Extensions and Comparative Analysis

Temporal and Modified Versions

In 2022, researchers proposed the temporal DPSIR (tDPSIR) framework as an adaptation of the original model to explicitly account for time-dependent dynamics, including lags between stages such as the delay from pressures to observable state changes or from responses to mitigated impacts.[28] This modification addresses the static limitations of standard DPSIR by incorporating interval durations and simplified time-dependent modeling, enabling quantification of temporal mismatches in environmental processes, such as prolonged accumulation of pollutants before impacts manifest.[37] For example, tDPSIR was applied to analyze marine pollution from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles, revealing governance lags of years between waste generation (drivers/pressures) and effective cleanup responses, which informed recommendations for databases tracking time delays in policy implementation.[38] Other temporal extensions emphasize dynamic evolution in DPSIR applications, integrating time-series data to evaluate changing ecological security patterns. In assessments of regional sustainability, such as in China's Shaanxi Province from 2005 to 2019, DPSIR models incorporated temporal indicators to track shifts in urban states and impacts, highlighting accelerating pressures from economic drivers over decades.[39] Similarly, spatial-temporal DPSIR variants have modeled coordinated development dynamics, using subsystem interactions to predict future states based on historical trends, as in ecological carrying capacity studies from 2005 to 2018, where response efficacy was found to lag state degradation by 5–10 years on average.[40] Modified versions beyond temporal focus include the DPSWR framework (Drivers-Pressures-State-Welfare-Responses), introduced in 2013 to replace impacts with welfare metrics for clearer linkage to human well-being outcomes in socio-ecological accounting.[41] This adaptation improves indicator alignment by emphasizing welfare changes over vague impact definitions, facilitating integrated assessments of environmental pressures on social systems. Additional variants extend DPSIR with iterative loops and uncertainty elements for policy design, incorporating risk assessments to handle non-linear feedbacks, as proposed in 2022 analyses of sustainable development where traditional linear causality was deemed insufficient for adaptive management.[42] These modifications, while enhancing flexibility, require empirical validation of added parameters to avoid overcomplication, with applications showing improved problem-structuring in coastal and urban contexts from 2015 onward.[43]Comparisons with PSR and DSR Frameworks

The Pressure-State-Response (PSR) framework, developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in the early 1990s, structures environmental analysis around human-induced pressures—such as pollution emissions or resource extraction—that alter the state of environmental systems, prompting policy or societal responses aimed at mitigation.[8] This model emphasizes causality from direct anthropogenic stresses to observable environmental conditions and reactive measures, but it conflates underlying socio-economic drivers with immediate pressures, limiting its ability to trace root causes.[44] The Driver-State-Response (DSR) framework, advanced by the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) in the mid-1990s, modifies PSR by prioritizing "driving forces"—broad socio-economic factors like population growth, economic activity, or technological change—as the initiators of environmental state alterations, followed by responses. Unlike PSR, DSR distinguishes ultimate drivers from their effects on state, enhancing focus on preventive interventions, yet it omits explicit links to ecological or human impacts, potentially underrepresenting consequences beyond state changes. In contrast, the DPSIR framework, formalized by the European Environment Agency (EEA) in 1999, builds on both PSR and DSR by inserting "pressures" (specific outputs like waste or habitat loss) between drivers and state, and adding "impacts" (effects on biodiversity, health, or welfare) between state and responses, forming a fuller causal chain with feedback loops.[1] This structure addresses PSR's merger of drivers and pressures by separating root socio-economic forces from proximate stressors, while extending DSR's driver focus with impacts to better illuminate human-environment interdependencies and inform targeted policies.[45] DPSIR's inclusion of impacts facilitates evaluation of state changes' real-world ramifications, which PSR and DSR largely imply but do not isolate, making it more adaptive for complex, dynamic systems like climate policy or biodiversity loss.[3]| Framework | Key Components | Primary Strengths | Limitations Relative to DPSIR |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSR | Pressures → State → Responses | Simple causality for indicator development; links direct human actions to policy needs.[44] | Lacks distinction between root drivers and pressures; no explicit impacts, reducing feedback clarity.[46] |

| DSR | Drivers → State → Responses | Emphasizes socio-economic origins over mere pressures; aids sustainable development reporting. | Omits pressures as intermediaries and impacts, potentially overlooking intermediate mechanisms and outcomes. |

| DPSIR | Drivers → Pressures → State → Impacts → Responses | Comprehensive causal mapping with feedbacks; better for interdisciplinary policy analysis.[1] | More complex, requiring detailed data across chains, which can challenge application in data-scarce contexts.[47] |