Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

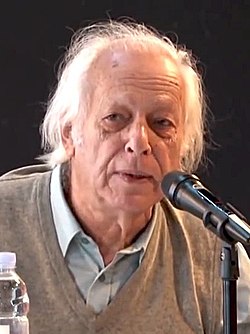

Samir Amin

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series about |

| Imperialism studies |

|---|

Samir Amin (Arabic: سمير أمين) (3 September 1931 – 12 August 2018) was an Egyptian-French Marxian economist,[1] political scientist and world-systems analyst. He is noted for his introduction of the term Eurocentrism in 1988[2] and considered a pioneer of dependency theory.[3]

Biography

[edit]Amin was born in Cairo, the son of a French mother and an Egyptian father (both medical doctors). He spent his childhood and youth in Port Said; there he attended a French high school, leaving in 1947 with a Baccalauréat.

It was at high school that Amin was first politicized when, during the Second World War, Egyptian students were split between communists and nationalists; Amin belonged to the former group. By then Amin had already adopted a resolute stance against fascism and Nazism. While the upheaval against British domination in Egypt informed his politics, he rejected the idea that the enemy of their enemy, Nazi Germany, was the Egyptians' friend.[4]

In 1947 Amin left for Paris where he obtained a second high school diploma with a specialization in elementary mathematics from the prestigious Lycée Henri IV. He gained a diploma in political science at Sciences Po (1952) before graduating in statistics at INSEE (1956) and also in economics (1957).

In his autobiography Itinéraire intellectuel (1990) he wrote that in order to spend a substantial amount of time in "militant action" he could devote only a minimum to preparing for his university exams. The intellectual and the political struggle remained inseparable for Amin all throughout his life. Rather than explaining the world and its atrocities he meant to highlight and to be part of struggles aimed at changing the world.[4]

After arriving in Paris, Amin joined the French Communist Party (PCF), but he later distanced himself from Soviet Marxism and associated himself for some time with Maoist circles. With other students he published a magazine entitled Étudiants Anticolonialistes. His ideas and political position were also strongly influenced by the 1955 Asian–African Bandung Conference and the nationalization of the Suez Canal. The latter even encouraged him to postpone his PhD thesis that was ready in June 1956 to take part in the political unrest.[4]

In 1957 he presented his thesis, supervised by François Perroux among others, originally titled The origins of underdevelopment – capitalist accumulation on a world scale but retitled The structural effects of the international integration of precapitalist economies. A theoretical study of the mechanism which creates so-called underdeveloped economies.

After finishing his thesis, Amin went back to Cairo, where he worked from 1957 to 1960 as a research officer for the government's "Institution for Economic Management" where he worked on ensuring the state's representation on the boards of directors of public sector companies while at the same time immersing himself in the very tense political climate linked to the nationalization of the Canal, the 1956 war and the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement. His participation in the Communist Party that was clandestine at the time made for very difficult working conditions.[4]

In 1960 Amin left for Paris where he worked for six months for the Department of Economic and Financial Studies - Service des Études Économiques et Financières (SEEF).

Subsequently, Amin left France, to become an adviser to the Ministry of Planning in Bamako (Mali) under the presidency of Modibo Keïta. He held that position from 1960 to 1963 working with prominent French economists such as Jean Bénard and Charles Bettelheim. With some scepticism Amin witnessed the growing emphasis on maximizing growth in order to "close the gap". Although he abandoned working as a 'bureaucrat' after he left Mali, Samir Amin continued to act as an adviser for several governments, such as China, Vietnam, Algeria, Venezuela, and Bolivia.[4]

In 1963 he was offered a fellowship at the UN's Institut Africain de Développement Économique et de Planification (IDEP) in Dakar. Within the IDEP Amin created several institutions that eventually became independent entities. Among them one that later became the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA), conceived on the model of the Latin American Council for Social Sciences (CLACSO).

Until 1970 he worked there as well as being a professor at the University of Poitiers, Dakar and Paris (of Paris VIII, Vincennes). In 1970 he became director of the IDEP, which he managed until 1980. In 1980 Amin left the IDEP and became a director of the Third World Forum in Dakar. In Amin's life and thinking the three activities have been closely connected: work in economic management, teaching/research, and the political struggle.[4]

"Samir Amin has been one of the most important and influential intellectuals of the Third World".[4] Amin's theoretical pioneering role has been often overlooked because his thesis of 1957 was not published until 1970 in extended book form under the title L'accumulation à l'échelle mondiale (Accumulation at the global level).[4]

Amin lived in Dakar until the end of July 2018. On July 31 he was, diagnosed with lung cancer, transferred to a hospital in Paris. Amin died on August 12 at the age of 86.

Political theory and strategy

[edit]Samir Amin is considered a pioneer of Dependency Theory and World System Theory, while he preferred to call himself part of the school of Global Historical Materialism, together with Paul A. Baran and Paul Sweezy.[3] His key idea, presented as early as 1957 in his Ph.D. dissertation, was that so-called 'under-developed' economies should not be considered as independent units but as building blocks of a capitalist world economy. In this world economy, the 'poor' nations form the 'periphery', forced to a permanent structural adjustment with respect to the reproduction dynamics of the 'centres' of the world economy, that is, of the advanced capitalist industrial countries. Around the same time and with similar basic assumptions the so-called desarrollismo (CEPAL, Raúl Prebisch) emerged in Latin America, which was developed further a decade later in the discussion on 'dependencia' – and even later appeared Wallerstein's 'world system analysis'. Samir Amin applied Marxism to a global level, using terms as 'law of worldwide value' and 'super-exploitation' to analyse the world-economy.[3][4] At the same time his critique extended also to Soviet Marxism and its development program of 'catching up and overtaking'.[4] Amin believed the countries of the 'periphery' would not be able to catch up in the context of a capitalist world-economy, because of the system's inherent polarization and certain monopolies held by the imperialist countries of the 'center'. Thus, he called for the 'periphery' to 'delink' from the world economy, creating 'autocentric' development and rejecting the 'Eurocentrism' inherent to Modernisation Theory.[3]

Global historical materialism

[edit]Resorting to the analyses of Karl Marx, Karl Polanyi, and Fernand Braudel, the central starting point of Samir Amin's theories is a fundamental critique of capitalism, at the centre of which is the conflict structure of the world system. Amin states three fundamental contradictions of capitalist ideology: 1. The requirements of profitability stand against the striving of the working people to determine their own fate (rights of workers as well as democracy were enforced against capitalist logic); 2. The short-term rational economic calculus stands against long-term safeguarding of the future (ecology debate); 3. The expansive dynamics of capitalism lead to polarizing spatial structures - the Center-Periphery Model.[5]

According to Amin, capitalism and its evolution can only be understood as a single integrated global system, composed of 'developed countries', which constitute the Center, and of 'underdeveloped countries', which are the Peripheries of the system. Development and underdevelopment consequently constitute both facets of the unique expansion of global capitalism. Underdeveloped countries should not be considered as 'lagging behind' because of the specific - social, cultural, or even geographic - characteristics of these so-called 'poor' countries. Underdevelopment is actually only the result of the forced permanent structural adjustment of these countries to the needs of the accumulation benefiting the system's Center countries.[4]

Amin identified himself as part of the school of global historical materialism, in contrast to the two other strands of dependency theory, the so-called dependencia and the World Systems Theory. The dependencia school was a Latin American school associated with e. g. Ruy Mauro Marini, Theotônio dos Santos, and Raúl Prebisch. Prominent figures of the World Systems Theory were Immanuel Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi.[3] While they use a widely similar scientific vocabulary, Amin rejected, for example, the notion of a semi-periphery and was against the theorization of capitalism as cyclical (as by Nikolai Kondratiev) or any kind of retrojection, thus holding a minority position among the World System theorists.[5]

For Amin, the school of global historical materialism was Marxism understood as a global system. Within this framework, the Marxist law of value is central (see 2.1.1).[3] Nevertheless, he insisted that the economic laws of capitalism, summed up by the law of value, are subordinate to the laws of historical materialism. In Amins understanding of these terms that is to say: economic science, while indispensable, cannot explain the full reality. Mainly because it cannot account either for the historical origins of the system itself, nor for outcomes of class struggle.[6]

History is not ruled by the infallible unfolding of the law of pure economy. It is created by the societal reactions to these tendencies that express themselves in these laws and that determine the social conditions in whose framework these laws operate. The 'anti-systemic' forces impact and also influence real history as does the pure logic of the capitalist accumulation. (Samir Amin)[4]

Law of worldwide value

[edit]Amin's theory of a global law of value describes a system of unequal exchange, in which the difference in the wages between labor forces in different nations is greater than the difference between their productivities. Amin talks of "imperial rents" accruing to the global corporations in the Center - elsewhere referred to as "global labor arbitrage".

Reasons are, according to Amin, that while free trade and relatively open borders allow multinationals to move to where they can find the cheapest labour, governments keep promoting the interests of 'their' corporations over those of other countries and restricting the mobility of labor.[6] Accordingly, the periphery is not really connected to global labour markets, accumulation there is stagnant, and wages stay low. In contrast, in the centres accumulation is cumulative and wages increase in accordance with rising productivity. This situation is perpetuated by the existence of a massive global reserve army located primarily in the periphery, while at the same time these countries are more structurally dependent, and their governments tend to oppress social movements which would win increased wages. This global dynamic Amin calls „development of underdevelopment".[7] The aforementioned existence of a lower rate of exploitation of labor in the North and a higher rate of exploitation of labor in the South is further thought to constitute one of the main obstacles to the unity of the international working class.[6]

According to Amin the "Global Law of Value" thus creates the "super-exploitation" of the periphery. Further, the core countries keep monopolies on technology, control of financial flows, military power, ideological and media production, and access to natural resources (see 2.1.2).[7]

Imperialism and monopoly capitalism

[edit]The system of worldwide value as described above means that there is one imperial world system, encompassing both the global North and the global South.[6] Amin further believed that capitalism and imperialism were linked at all stages of their development (as opposed to Lenin, who argued that imperialism was a specific stage in the development of capitalism).[4] Amin defined imperialism as: "precisely the amalgamation of the requirements and laws for the reproduction of capital; the social, national and international alliances that underlie them; and the political strategies employed by these alliances".[6]

According to Amin, capitalism and imperialism reach from the conquest of the Americas during the sixteenth century to today's phase of what he referred to as "monopoly capitalism". Further, the polarization between Center and Peripheries is a phenomenon inherent in historical capitalism. Resorting to Arrighi, Amin differentiates the following mechanism of polarization: 1. The capital flight takes place from the periphery to the centre; 2. Selective migration of workers is heading in the same direction; 3. Monopoly situation of the central companies in the global division of labour, in particular, the technology monopoly and the monopoly of global finances; 4. Control of centres on access to natural resources.[5] The forms of the Center-Peripheries polarization, as well as the forms of expression of imperialism, have changed over time - but always towards the aggravation of the polarization and not towards its mitigation.[4]

Historically, Amin differentiated three phases: Mercantilism (1500-1800), Expansion (1800-1880) and Monopoly Capitalism (1880-today). Amin adds that the current phase is dominated by generalized, financialized, and globalized oligopolies located primarily in the triad of USA, Europe, and Japan.[6] They practice a sort of collective imperialism by means of military, economic, and financial tools such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Trade Organization (WTO). The triad enjoys the monopoly of five advantages: weapons of mass destruction; mass communication systems; monetary and financial systems; technologies; and access to natural resources. It wishes to keep these at any cost and thus has engaged in the militarization of the world in order to avoid losing these monopolies.[4]

Amin further differentiated the existence of two historical phases of the development of monopoly capitalism: proper monopoly capitalism up to 1971, and oligopoly-finance capitalism after that. The Financialization and "deepened globalization" of the latter he considered a strategic response to Stagnation. Stagnation he considered as the rule and rapid economic growth as the exception under late capitalism. According to him, the rapid growth of 1945–1975 was mainly the product of historical conditions brought into being by the Second World War and could not last. The focus on Financialization, which emerged in the late 1970s, to him was a new more potent counter to stagnation "inseparable from the survival requirements of the system", but eventually leading to the financial crisis 2007-2008.[6]

According to Amin, as a result of imperialism and super-exploitation, political systems in the south are often distorted towards forms of autocratic rule. To maintain control over the periphery, the imperial powers promote backwards-looking social relations drawing on archaic elements. Amin argues for example that political Islam is chiefly a creature of imperialism. The introduction of democracy in the South, without altering the fundamental social relations or challenging imperialism, is nothing but a "fraud" and doubly so given the plutocratic content of the so-called successful democracies in the North.[6]

Delinking

[edit]Amin forcefully stated that the emancipation of the so-called 'underdeveloped' countries can neither happen while respecting the logic of the globalized capitalist system nor within this system. The South would not be able to catch up in such a capitalist context, because of the system's inherent polarization. This belief led Samir Amin to assign significant importance to the project adopted by the Asian–African countries at the Bandoeng (Indonesia) Conference in 1955.[4]

Amin called for each country to delink from the world economy meaning to subordinate global relations to domestic development priorities, creating 'autocentric' development (but not autarky).[3] Instead of defining value by dominant prices in the world – which result from productivity in the rich countries – Amin suggested that value in each country should be set so that agricultural and industrial workers are paid by their input into the society's net output. Thereby a National Law of Value should be defined without reference to the Global Law of Value of the capitalist system (e.g. food sovereignty instead of free trade, minimum wages instead of international competitiveness, full employment guaranteed by government). Amin suggested that national states redistribute resources between sectors, and centralize and distribute the surplus. Full employment should be guaranteed, and the exodus from rural to urban areas discouraged.[7]

After the decolonization on a state level, this should lead to economic liberation from neo-colonialism. However, Amin underlined that it is almost impossible to delink 100% and estimated a delinking of 70% already a significant achievement. Relatively stable countries with some military power have more leverage in this regard than small countries.[citation needed]

China's development for example is, according to Amin, determined 50% by its sovereign project and 50% by globalisation. When asked about Brazil and India, he estimated that their trajectories were driven by 20% sovereign project, and 80% globalisation, while South Africa was determined by 0% sovereign project and 100% globalisation.[3]

It was also clear to Amin that such decoupling also requires certain political prerequisites within a country. His country studies, initially limited to Africa, taught him that a national bourgeoisie geared towards a national project, neither existed nor was it emerging. Rather, he observed the emergence of a 'comprador bourgeoisie', who benefited from the integration of their respective countries into the asymmetrically structured capitalist world market. Regarding the project of an auto-centered new beginning (the decoupling) he hoped instead for social movements, which is why he was committed to numerous non-governmental organizations until the end.[4]

Eurocentrism

[edit]Amin proposed a history of civilization in which accidental advantages of the "West" led to the development of capitalism first in these societies. This then created a global rift, arising from the aggressive outward expansion of capitalism and colonialism.[6] Amin argues that it is a mistake to view Europe as a historical centre of the world. Only in the capitalist period has Europe been dominant.[citation needed]

For Amin, Eurocentrism is not only a worldview but a global project, homogenising the world on a European model under the pretext of 'catching-up'. In practice, however, capitalism does not homogenise but rather polarises the world. Eurocentrism is thus more of an ideal than a real possibility. It also creates problems in reinforcing racism and imperialism. Fascism remains a permanent risk, because to Amin it is an extreme version of Eurocentrism.[7]

Cambodia

[edit]Amin was long an influence on and supporter of the leaders of Cambodia's Khmer Rouge regime, becoming acquainted with the Khmer Rouge's future leaders in post-World War II Paris, where Pol Pot, Khieu Samphan, and other Cambodian students were studying. Khieu Samphan's doctoral thesis, which he finished in 1959, noted collaborations with Amin and claimed to apply Amin's theories to Cambodia.[8][9] In the late 1970s, Amin praised the Khmer Rouge as superior to Communist movements in China, Vietnam, or the Soviet Union, and recommended the Khmer Rouge model for Africa.[10]

Amin continued to actively praise the Khmer Rouge into the 1980s. At a 1981 talk in Tokyo, Amin praised Pol Pot's work as "one of the major successes of the struggle for socialism in our era" and as necessary against "expansionism" from the Soviet Union or from Vietnam.[11] Some scholars, such as Marxist anthropologist Kathleen Gough, have noted that Khmer Rouge activists in Paris in the 1950s already held ideas of eliminating counter-revolutionaries and organizing a party center whose decisions could not be questioned.[11] Despite contemporary reports of mass killings committed by the Khmer Rouge, Amin argued that "the cause of the most evil to the people of Kampuchea" lay elsewhere:

The humanitarian argument is in the final analysis the argument offered by all the colonialists... Isn't [the cause of evil] first of all the American imperialists and Lon Nol? Isn't it today the Vietnamese army and their project of colonizing Kampuchea?[12]

Views on world order

[edit]Samir Amin expressed view on world order and international relations: "Yes, I do want to see the construction of a multipolar world, and that obviously means the defeat of Washington's hegemonic project for military control of the planet."[13]

In 2006, he stated:

Here I would make the first priority the construction of a Paris – Berlin – Moscow political and strategic alliance, extended if possible to Beijing and Delhi … to build military strength at a level required by the challenge of the United States... [E]ven the United States pales beside their traditional capacities in the military arena. The American challenge, and Washington's criminal designs, make such a course necessary … The creation of a front against hegemonism is the number one priority today, as the creation of an anti-Nazi alliance was … yesterday … A rapprochement between the large portions of Eurasia (Europe, Russia, China and India) involving the rest of the Old World … is necessary and possible, and would put an end once and for all to Washington's plans to extend the Monroe Doctrine to the entire planet. We must head in this direction … above all with determination."[14]

He also stated:

The 'European project' is not going in the direction that is needed to bring Washington to its senses. Indeed, it remains a basically 'non-European' project, scarcely more than the European part of the American project … Russia, China and India are the three strategic opponents of Washington's project... But they appear to believe that they can maneuver and avoid directly clashing with the United States.[15]

Hence, Europe must end its "Atlanticist option" and take the course of the "Eurasian rapprochement" with Russia, China, India and the rest of Asia and Africa. This "Eurasian rapprochement" is necessary for the head-on collision with the United States.[16]

Views on political Islam

[edit]While his personal religious beliefs are unknown, Samir Amin was a harsh critic of political Islam and Islamism.

According to Samir Amin, political Islam leads its struggle on the terrain of culture, wherein "culture" is intended as "belongingness to one religion". Islamist militants are not actually interested in the discussion of dogmas which form religion, but on the contrary are concerned about the ritual assertion of membership in the community. Such a world view is therefore not only distressing, as it conceals an immense poverty of thought, but it also justifies imperialism's strategy of substituting a "conflict of cultures" for a conflict between the liberal, imperialist centres and the backward, dominated peripheries.

Amin argued that this importance attributed to culture allows political Islam to obscure from every sphere of life the realistic social dichotomy between the working classes and the global capitalist system which oppresses and exploits them.[17]

Besides, beyond being reactionary on definite matters (such as that regarding women) and being responsible for fanatical excesses against non-Muslim citizen (such as the Copts in Egypt), political Islam even defends the sacred character of property and legitimises inequality and all the prerequisites of capitalist reproduction.[18]

Hence, political Islam aligns itself in general with capitalism and imperialism, without providing the working classes with an effective and non-reactionary method of struggle against their exploitation.[19]

It is important to note, however, that Amin was careful to distinguish his analysis of political Islam from Islamophobia, thus remaining sensitive to the anti-Muslim attitudes that currently affect Western Society.[20]

Awards

[edit]- The Ibn Rushd Prize for Freedom of Thought for the year 2009 in Berlin.

Publications

[edit]- 1957, Les effets structurels de l'intégration internationale des économies précapitalistes. Une étude théorique du mécanisme qui an engendré les éonomies dites sous-développées (thesis)

- 1965, Trois expériences africaines de développement: le Mali, la Guinée et le Ghana

- 1966, L'économie du Maghreb, 2 vols.

- 1967, Le développement du capitalisme en Côte d'Ivoire

- 1969, Le monde des affaires sénégalais

- 1969, The Class struggle in Africa[21]

- 1970, Le Maghreb moderne (translation: The Maghreb in the Modern World)

- 1970, L'accumulation à l'échelle mondiale (translation: Accumulation on a world scale)

- 1970, with C. Coquery-Vidrovitch, Histoire économique du Congo 1880–1968

- 1971, L'Afrique de l'Ouest bloquée

- 1973, Le développement inégal (translation: Unequal development)

- 1973, L'échange inégal et la loi de la valeur

- 1973, 'Le developpement inegal. Essai sur les formations sociales du capitalisme peripherique' Paris: Editions de Minuit.

- 1974, Neocolonialism in West Africa[22]

- 1974, with K. Vergopoulos: La question paysanne et le capitalisme

- 1975, with A. Faire, M. Hussein and G. Massiah: La crise de l'impérialisme

- 1976, 'Unequal Development: An Essay on the Social Formations of Peripheral Capitalism' New York: Monthly Review Press.

- 1976, L'impérialisme et le développement inégal (translation: Imperialism and unequal development)

- 1976, La nation arabe (translation: The Arab Nation)

- 1977, The lessons of Cambodia

- 1977, La loi de la valeur et le matérialisme historique (translation: The law of value and historical materialism)

- 1979, Classe et nation dans l'histoire et la crise contemporaine (translation: Class and nation, historically and in the current crisis)

- 1980, L'économie arabe contemporaine (translation: The Arab economy today)

- 1981, L'avenir du Maoïsme (translation: The Future of Maoism)

- 1982, Irak et Syrie 1960–1980

- 1982, with G. Arrighi, A. G. Frank and I. Wallerstein): La crise, quelle crise? (translation: Crisis, what crisis?)

- 1984, 'Was kommt nach der Neuen Internationalen Wirtschaftsordnung? Die Zukunft der Weltwirtschaft' in 'Rote Markierungen International' (Fischer H. and Jankowitsch P. (Eds.)), pp. 89–110, Vienna: Europaverlag.

- 1984, Transforming the world-economy? : nine critical essays on the new international economic order.

- 1985, La déconnexion (translation: Delinking: towards a polycentric world)

- 1988, Impérialisme et sous-développement en Afrique (expanded edition of 1976)

- 1988, L'eurocentrisme (translation: Eurocentrism)

- 1988, with F. Yachir: La Méditerranée dans le système mondial

- 1989, La faillite du développement en Afrique et dans le tiers monde

- 1990, with Andre Gunder Frank, Giovanni Arrighi and Immanuel Wallerstein: Transforming the revolution: social movements and the world system

- 1990, Itinéraire intellectuel; regards sur le demi-siècle 1945-90 (translation: Re-reading the post-war period: an Intellectual Itinerary)

- 1991, L'Empire du chaos (translation: Empire of chaos)

- 1991, Les enjeux stratégiques en Méditerranée

- 1991, with G. Arrighi, A. G. Frank et I. Wallerstein): Le grand tumulte

- 1992, 'Empire of Chaos' New York: Monthly Review Press[23]

- 1994, L'Ethnie à l'assaut des nations

- 1995, La gestion capitaliste de la crise

- 1996, Les défis de la mondialisation

- 1997, 'Die Zukunft des Weltsystems. Herausforderungen der Globalisierung. Herausgegeben und aus dem Franzoesischen uebersetzt von Joachim Wilke' Hamburg: VSA.

- 1997, Critique de l'air du temps

- 1999, "Judaism, Christianity and Islam: An Introductory Approach to their Real or Supposed Specificities by a Non-Theologian" in "Global capitalism, liberation theology, and the social sciences: An analysis of the contradictions of modernity at the turn of the millennium" (Andreas Mueller, Arno Tausch and Paul Zulehner (Eds.)), Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, Commack, New York

- 1999, Spectres of capitalism: a critique of current intellectual fashions

- 2000, L'hégémonisme des États-Unis et l'effacement du projet européen

- 2002, Mondialisation, comprendre pour agir

- 2003, Obsolescent Capitalism

- 2004, The Liberal Virus: Permanent War and the Americanization of the World

- 2005, with Ali El Kenz, Europe and the Arab world; patterns and prospects for the new relationship

- 2006, Beyond US Hegemony: Assessing the Prospects for a Multipolar World

- 2007, 'A Life Looking Forward: Memoirs of an Independent Marxist'

- 2008, with James Membrez, The World We Wish to See: Revolutionary Objectives in the Twenty-First Century

- 2009, 'Aid for Development' in 'Aid to Africa: Redeemer or Coloniser?' Oxford: Pambazuka Press

- 2010, 'Eurocentrism - Modernity, Religion and Democracy: A Critique of Eurocentrism and Culturalism' 2nd edition, Oxford: Pambazuka Press [1] Archived 22 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- 2010, 'Ending the Crisis of Capitalism or Ending Capitalism?' Oxford: Pambazuka Press

- 2010, 'Global History - a View from the South' Oxford: Pambazuka Press

- 2011, 'Maldevelopment - Anatomy of a Global Failure' 2nd edition, Oxford: Pambazuka Press[24]

- 2011, 'Imperialism and Globalization' : Monthly Review Press[25]

- 2013, 'The Implosion of Contemporary Capitalism': Monthly Review Press[26]

- 2016, 'Russia and the Long Transition from Capitalism to Socialism': Monthly Review Press[27]

- 2017, October 1917 Revolution: A Century Later. Wakefield, Canada: Daraja Press.[28]

- 2018, 'Modern Imperialism, Monopoly Finance Capital, and Marx's Law of Value': Monthly Review Press[29]

- 2019, 'The Long Revolution of the Global South: Toward a New Anti-Imperialist International' - Memoirs (adapted translation of 'L'Éveil du Sud'): [30]

- 2019, 'Only People Make Their Own History: Writings on Capitalism, Imperialism, and Revolution'

References

[edit]- ^ "Samir Amin at 80". Red Pepper. Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ "A Brief Biography of Samir Amin". Monthly Review, Vol. 44, Issue 4, September 1992. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kvangraven, I. H. (2017). A Dependency Pioneer: Samir Amin. p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Brauch, Günter Hans (2014). Springer Briefs on Pioneers in Science and Practice: Volume 16: Samir Amin Pioneer of the Rise of the South. Springer Verlag. pp. vi, vii, xiii, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 143.

- ^ a b c Germ, Alfred (1997). Wilke, Joachim (ed.). Zum Weltsystemansatz von Samir Amin. Vol. Die Zukunft des Weltsystems: Herausforderungen der Globalisierung. Hamburg: VSA-Verlag.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Foster, John Bellamy (2011). "Samir Amin at 80: An Introduction and Tribute". Monthly Review. 63 (5): 1. doi:10.14452/MR-063-05-2011-09_1.

- ^ a b c d Robinson, A. (2011). "An A-Z of theory: Samir Amin Part 2". Ceasefire Magazine. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Khieu Samphan (September–November 1976). Underdevelopment in Cambodia. Berkeley, CA: Indochina Resource Center. pp. 51–52.

- ^ "Specters of Dependency: Hou Yuon and the Origins of Cambodia's Marxist Vision (1955–1975) | Cross-Currents". cross-currents.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Jackson, Karl (2014). Cambodia, 1975-1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press. p. 246. ISBN 9781400851706.

- ^ a b Gough, Kathleen (Spring 1986). "Roots of the Pol Pot Regime in Kampuchea". Contemporary Marxism (12/13).

- ^ Amin, Samir (1986). "The Struggle for National Independence and Socialism in Kampuchea". Contemporary Marxism (12/13).

- ^ Samir Amin, Beyond US Hegemony? Assessing the Prospects for a Multipolar World, (Beirut: World Book Publishing, 2006), p 17.

- ^ Beyond US Hegemony, p 17.

- ^ Beyond US Hegemony, p 148-149.

- ^ Beyond US Hegemony, p 148-149.

- ^ page 83, "The World We Wish To See; Revolutionary Objectives In The Twenty-First Century", Samir Amin and James Membrez, ISBN 1-58367-172-2, ISBN 978-1-58367-172-6, ISBN 978-1-58367-172-6, Publishing Date: Jul 2008, Publisher: Monthly Review Press

- ^ Amin, Samir (2010). The law of worldwide value. Samir Amin. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-234-1. OCLC 630467526.

- ^ page 84, "The World We Wish To See; Revolutionary Objectives In The Twenty-First Century", Samir Amin and James Membrez, ISBN 1-58367-172-2, ISBN 978-1-58367-172-6, ISBN 978-1-58367-172-6, Publishing Date: Jul 2008, Publisher: Monthly Review Press

- ^ "Comments on Tariq Amin-Khan's text by Samir Amin | Monthly Review". Monthly Review. 21 March 2009. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ WorldCat

- ^ Neocolonialism in West Africa

- ^ Empire of Chaos by Samir Amin

- ^ "Maldevelopment - Anatomy of a Global Failure. Samir Amin". Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Imperialism and Globalization

- ^ The Implosion of Contemporary Capitalism

- ^ Russia and the Long Transition from Capitalism to Socialism

- ^ Amin, Samir (2017). October 1917 Revolution: A Century Later. Wakefield, Canada: Daraja Press. ISBN 978-1-988832-05-0.

- ^ Modern Imperialism, Monopoly Finance Capital, and Marx's Law of Value

- ^ Long Revolution of the Global South

Further reading

[edit]- Aidan Forster-Carter: "The Empirical Samir Amin", in S. Amin: The Arab Economy Today, London, 1982, pp. 1–40

- Duru Tobi: "On Amin's Concepts - autocentric/ blocked development in Historical Perspectives", in: Economic Papers (Warsaw), No. 15, 1987, pp. 143–163

- Fouhad Nohra: Théories du capitalisme mondial. Paris, 1997

- Gerald M. Meier, Dudley Seers (eds.): Pioneers in Development. Oxford, 1984

- Kufakurinani, U.: Styve, M. D.; Kvangraven, I. H. (2019): Samir Amin and beyond, available at: https://africasacountry.com/2019/03/samir-amin-and-beyond [Accessed 05 Juni 2019]

- Senghaas, D. (2009): Zeitdiagnostik, von kreativer Utopie inspiriert: Laudatio auf Samir Amin aus Anlass der Verleihung des Ibn Rushd-Preises für Freies Denken am 4. Dezember 2009 in Berlin, available at: https://www.ibn-rushd.org/typo3/cms/de/awards/2009-samir-amin/laudatory-held-prof-dieter-senghaas/ [Accessed 4 Jun. 2019]

- Wilke, Joachim (2005): Samir Amins Projekt eines langen Weges zu einem globalen Sozialismus; in Vielfalt sozialistischen Denkens: Ausgabe 13, Berlin, Helle Panke e. V.

External links

[edit]- Empire of Chaos Challenged: An Interview with Samir Amin

- "Third World Forum: An Interview with Samir Amin," Z Magazine

- 2005 Interview with Samir Amin

- The New Challenge of the Peoples' Internationalism - Interview

- 2010 Interview with Samir Amin

- 2012 Interview with Samir Amin

- Revolutionary Change in Africa: An Interview with Samir Amin

- Samir Amin Articles at Monthly Review

- Samir Amin Articles at MR Online

- Samir Amin. New Empire? In Search of Alternatives to Global Hegemony of Capital. (Red TV)

- A review of Samir Amin's Re-reading the Postwar Period: An Intellectual Itinerary

- Revolution and the Third World: Exploring the Radical Ideas of Anti-Imperialist Economist Samir Amin by Ben Norton

- Samir Amin: a vital challenge to dispossession by Nick Dearden

- Samir Amin: Comrade in the Struggle by Immanuel Wallerstein

.jpg/250px-Samir_Amin_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)