Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dodecagon

View on Wikipedia| Regular dodecagon | |

|---|---|

A regular dodecagon | |

| Type | Regular polygon |

| Edges and vertices | 12 |

| Schläfli symbol | {12}, t{6}, tt{3} |

| Coxeter–Dynkin diagrams | |

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (D12), order 2×12 |

| Internal angle (degrees) | 150° |

| Properties | Convex, cyclic, equilateral, isogonal, isotoxal |

| Dual polygon | Self |

In geometry, a dodecagon, or 12-gon, is any twelve-sided polygon.

Regular dodecagon

[edit]

A regular dodecagon is a figure with sides of the same length and internal angles of the same size. It has twelve lines of reflective symmetry and rotational symmetry of order 12. A regular dodecagon is represented by the Schläfli symbol {12} and can be constructed as a truncated hexagon, t{6}, or a twice-truncated triangle, tt{3}. The internal angle at each vertex of a regular dodecagon is 150°.

Area

[edit]The area of a regular dodecagon of side length a is given by:

And in terms of the apothem r (see also inscribed figure), the area is:

In terms of the circumradius R, the area is:[1]

The span S of the dodecagon is the distance between two parallel sides and is equal to twice the apothem. A simple formula for area (given side length and span) is:

This can be verified with the trigonometric relationship:

Perimeter

[edit]The perimeter of a regular dodecagon in terms of circumradius is:[2]

The perimeter in terms of apothem is:

This coefficient is double the coefficient found in the apothem equation for area.[3]

Dodecagon construction

[edit]As 12 = 22 × 3, regular dodecagon is constructible using compass-and-straightedge construction:

at a given side length, animation. (The construction is very similar to that of octagon at a given side length.)

Dissection

[edit]| 12-cube | 60 rhomb dissection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

Coxeter states that every zonogon (a 2m-gon whose opposite sides are parallel and of equal length) can be dissected into m(m-1)/2 parallelograms.[4] In particular this is true for regular polygons with evenly many sides, in which case the parallelograms are all rhombi. For the regular dodecagon, m=6, and it can be divided into 15: 3 squares, 6 wide 30° rhombs and 6 narrow 15° rhombs. This decomposition is based on a Petrie polygon projection of a 6-cube, with 15 of 240 faces. The sequence OEIS sequence A006245 defines the number of solutions as 908, including up to 12-fold rotations and chiral forms in reflection.

6-cube |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the ways the mathematical manipulative pattern blocks are used is in creating a number of different dodecagons.[5] They are related to the rhombic dissections, with 3 60° rhombi merged into hexagons, half-hexagon trapezoids, or divided into 2 equilateral triangles.

|

|

Socolar tiling |

Pattern blocks |

Symmetry

[edit]

The regular dodecagon has Dih12 symmetry, order 24. There are 15 distinct subgroup dihedral and cyclic symmetries. Each subgroup symmetry allows one or more degrees of freedom for irregular forms. Only the g12 subgroup has no degrees of freedom but can be seen as directed edges.

| Example dodecagons by symmetry | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

r24 | ||||||

d12 |

g12 |

p12 |

i8 | |||

d6 |

g6 |

p6 |

d4 |

g4 |

p4 | |

g3 |

d2 |

g2 |

p2 | |||

a1 | ||||||

Occurrence

[edit]Tiling

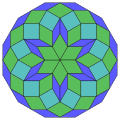

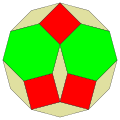

[edit]A regular dodecagon can fill a plane vertex with other regular polygons in 4 ways:

|

|

|

|

| 3.12.12 | 4.6.12 | 3.3.4.12 | 3.4.3.12 |

|---|

Here are 3 example periodic plane tilings that use regular dodecagons, defined by their vertex configuration:

| 1-uniform | 2-uniform | |

|---|---|---|

3.12.12 |

4.6.12 |

3.12.12; 3.4.3.12 |

Skew dodecagon

[edit]

A skew dodecagon is a skew polygon with 12 vertices and edges but not existing on the same plane. The interior of such a dodecagon is not generally defined. A skew zig-zag dodecagon has vertices alternating between two parallel planes.

A regular skew dodecagon is vertex-transitive with equal edge lengths. In 3-dimensions it will be a zig-zag skew dodecagon and can be seen in the vertices and side edges of a hexagonal antiprism with the same D5d, [2+,10] symmetry, order 20. The dodecagrammic antiprism, s{2,24/5} and dodecagrammic crossed-antiprism, s{2,24/7} also have regular skew dodecagons.

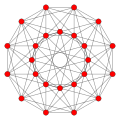

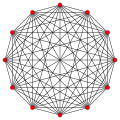

Petrie polygons

[edit]The regular dodecagon is the Petrie polygon for many higher-dimensional polytopes, seen as orthogonal projections in Coxeter planes. Examples in 4 dimensions are the 24-cell, snub 24-cell, 6-6 duoprism, 6-6 duopyramid. In 6 dimensions 6-cube, 6-orthoplex, 221, 122. It is also the Petrie polygon for the grand 120-cell and great stellated 120-cell.

| Regular skew dodecagons in higher dimensions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E6 | F4 | 2G2 (4D) | |||

221 |

122 |

24-cell |

Snub 24-cell |

6-6 duopyramid |

{6}×{6} |

| A11 | D7 | B6 | 4A2 | ||

11-simplex |

(411) |

141 |

6-orthoplex |

6-cube |

{3}×{3}×{3}×{3} |

Related figures

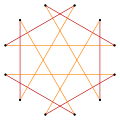

[edit]A dodecagram is a 12-sided star polygon, represented by symbol {12/n}. There is one regular star polygon: {12/5}, using the same vertices, but connecting every fifth point. There are also three compounds: {12/2} is reduced to 2{6} as two hexagons, and {12/3} is reduced to 3{4} as three squares, {12/4} is reduced to 4{3} as four triangles, and {12/6} is reduced to 6{2} as six degenerate digons.

| Stars and compounds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Form | Polygon | Compounds | Star polygon | Compound | ||

| Image |  {12/1} = {12} |

{12/2} or 2{6} |

{12/3} or 3{4} |

{12/4} or 4{3} |

{12/5} |

{12/6} or 6{2} |

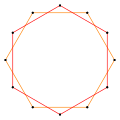

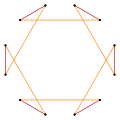

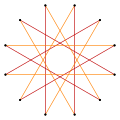

Deeper truncations of the regular dodecagon and dodecagrams can produce isogonal (vertex-transitive) intermediate star polygon forms with equal spaced vertices and two edge lengths. A truncated hexagon is a dodecagon, t{6}={12}. A quasitruncated hexagon, inverted as {6/5}, is a dodecagram: t{6/5}={12/5}.[7]

| Vertex-transitive truncations of the hexagon | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quasiregular | Isogonal | Quasiregular | |

t{6}={12} |

|

|

t{6/5}={12/5} |

Examples in use

[edit]In block capitals, the letters E, H and X (and I in a slab serif font) have dodecagonal outlines. A cross is a dodecagon, as is the logo for the Chevrolet automobile division.

The regular dodecagon features prominently in many buildings. The Torre del Oro is a dodecagonal military watchtower in Seville, southern Spain, built by the Almohad dynasty. The early thirteenth century Vera Cruz church in Segovia, Spain is dodecagonal. Another example is the Porta di Venere (Venus' Gate), in Spello, Italy, built in the 1st century BC has two dodecagonal towers, called "Propertius' Towers".

Regular dodecagonal coins include:

- British threepenny bit from 1937 to 1971, when it ceased to be legal tender.

- British One Pound Coin, introduced in 2017.

- Australian 50-cent coin

- Fijian 50 cents

- Tongan 50-seniti, since 1974

- Solomon Islands 50 cents

- Croatian 25 kuna

- Romanian 5000 lei, 2001–2005

- Canadian penny, 1982–1996

- South Vietnamese 20 đồng, 1968–1975

- Zambian 50 ngwee, 1969–1992

- Malawian 50 tambala, 1986–1995

- Mexican 20 centavos, 1992-2009

- Israeli 5 new shekel

See also

[edit]- Dodecagonal number

- Dodecahedron – any polyhedron with 12 faces.

- Dodecagram

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Wolfram Demonstrations Project". demonstrations.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2025-02-04.

- ^ Willis, Clarence Addison (1922). Plane Geometry: Experiment, Classification, Discovery, Application ... B. Blakiston's Son & Company. p. 249.

- ^ Playfair, John (1814). Elements of Geometry. Bell & Bradfute. p. 243.

- ^ Coxeter, Mathematical recreations and Essays, Thirteenth edition, p.141

- ^ "Doin' Da' Dodeca'" on mathforum.org

- ^ John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, (2008) The Symmetries of Things, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 20, Generalized Schaefli symbols, Types of symmetry of a polygon pp. 275–278)

- ^ The Lighter Side of Mathematics: Proceedings of the Eugène Strens Memorial Conference on Recreational Mathematics and its History, (1994), Metamorphoses of polygons, Branko Grünbaum

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Dodecagon". MathWorld.

- Kürschak's Tile and Theorem

- Definition and properties of a dodecagon With interactive animation

- The regular dodecagon in the classroom, using pattern blocks

Dodecagon

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A dodecagon is any polygon with twelve sides and twelve vertices in the Euclidean plane.[1] As a general -gon where , it forms a closed figure bounded by straight line segments connecting the vertices in a cyclic order.[6] The sum of the interior angles of a dodecagon is , derived from dividing the polygon into triangles and summing their angles.[6] The sum of its exterior angles, one at each vertex, totals regardless of the specific shape, as they complete a full rotation around the figure.[6] Dodecagons are classified as convex if all interior angles are less than and no sides bend inward, or concave if at least one interior angle exceeds .[6] They may also be simple, with non-intersecting sides, or self-intersecting, where sides cross to form a more complex star-like shape.[6] The regular dodecagon, featuring equal sides and angles, represents a symmetric case explored further in subsequent sections. The dodecagon first appeared in ancient Greek geometry as part of broader studies on regular polygons, including constructions derived from bisecting arcs of inscribed hexagons.[7]Etymology

The term "dodecagon" derives from Ancient Greek δώδεκα (dṓdeka), meaning "twelve," combined with γωνία (gonía), meaning "angle" or "corner."[8] This etymological structure parallels the naming convention for other polygons, such as "hexagon" from ἕξ (héx, "six") and γωνία, or "decagon" from δέκα (déka, "ten") and γωνία.[9] The word entered English in the mid-17th century, with the first known usage recorded around 1658, borrowed ultimately from the Greek δωδεκάγωνον (dōdekágōnon).[9] It appears to have been introduced via French dodécagone, which itself dates to the 17th century as a direct adaptation of the Greek compound.[10] An alternative English term, "duodecagon," reflects Latin influence through duodecim ("twelve") prefixed to the Greek-derived "-gon," though it remains rare and largely archaic in mathematical contexts today. Over time, the nomenclature for polygons like the dodecagon standardized in mathematical literature, transitioning from descriptive phrases in classical texts—such as Archimedes' discussions of 12-sided inscribed figures in his approximation of π—to the consistent use of Greek-rooted terms in modern geometry since the Renaissance.Regular Dodecagon

Construction

A regular dodecagon is constructible using a compass and straightedge because 12 = 2² × 3, where 3 is a distinct Fermat prime; this factorization ensures that the central angle of 30° (or 2π/12 radians) can be obtained through a finite sequence of quadratic field extensions starting from the rationals.[11] The Euler totient function φ(12) = 4, which is a power of 2, further confirms that the minimal polynomial for cos(2π/12) has degree 2, making it solvable by radicals via compass and straightedge operations.[11] The primary method inscribes the dodecagon in a circle by first constructing a regular hexagon to divide the circle into six 60° arcs and then bisecting each arc to obtain the 30° increments.[12] This approach leverages the ease of hexagon construction and standard bisection techniques. To perform the construction:- Draw a circle centered at O with arbitrary radius r. Select a point A on the circumference and draw a second circle centered at A with radius r; it intersects the original circle at two points—choose one as B to start. Repeat by centering the compass at B with radius r to find C, then at C for D, at D for E, and at E for F; F will connect back near A, completing the six vertices A, B, C, D, E, F of the inscribed regular hexagon at 60° intervals.[12]

- For each adjacent pair of hexagon vertices, such as A and B, construct the midpoint M of chord AB: Set the compass to a radius greater than half AB, draw an arc above AB from A and another from B; these arcs intersect at a point P. Repeat below AB to find Q. Draw the straight line through P and Q; its intersection with AB is M.[12]

- Draw the line from O through M, extending it to intersect the original circle again at point G (the midpoint of the 60° arc AB). Repeat this bisection process for all six hexagon sides to obtain the remaining six points. The 12 points (hexagon vertices plus arc midpoints) are equally spaced at 30° intervals.[12]

- Connect the 12 points in angular order around the circle using the straightedge to form the regular dodecagon.[12]

Dimensions and Formulas

A regular dodecagon has an interior angle of exactly 150 degrees, calculated as for .[16] The perimeter of a regular dodecagon with side length is simply .[16] The area in terms of the side length is derived from the general formula for a regular -gon, , yielding for . Since , this simplifies to .[16][17] Alternatively, the area in terms of the circumradius (the radius of the circumscribed circle) is , obtained from with .[16] The side length in terms of the circumradius is given by , where , so .[16][17] The central angle between adjacent vertices is 30 degrees, as .[16]Symmetry

The regular dodecagon exhibits the full symmetry of the dihedral group , which has 24 elements consisting of 12 rotational symmetries and 12 reflectional symmetries. This group captures all isometries that map the figure onto itself, preserving its regular structure.[18] The rotational symmetries are generated by rotations about the center by angles that are integer multiples of , yielding elements of orders 1 (identity), 2 (), 3 (), 4 (), 6 (), and 12 (full ). These rotations form a cyclic subgroup of order 12, acting transitively on the vertices and edges.[18] The 12 reflectional symmetries occur across axes passing through the center: six axes connect pairs of opposite vertices, and the remaining six connect the midpoints of pairs of opposite sides. This arrangement arises because the dodecagon has an even number of sides, dividing the reflection axes evenly between vertex and edge types.[19] The fundamental domain under the action of comprises of the dodecagon, representing the smallest region that, when acted upon by the full group, covers the entire figure without overlap. The regular dodecagon is isogonal, meaning its symmetry group acts transitively on both vertices and edges, resulting in uniform vertex and edge configurations; its isogonal conjugate coincides with itself due to its self-dual nature under the Schläfli symbol {12}.[20][3]Advanced Geometric Properties

Dissection

A regular dodecagon can be divided into 12 congruent isosceles triangles by drawing radii from the center to each of the 12 vertices; each triangle has a central apex angle of 30° and two equal base angles of 75°.[21] This partitioning highlights the dodecagon's rotational symmetry and serves as a foundational method for deriving its area as 12 times the area of one such triangle. Albrecht Dürer provided compass and straightedge constructions for regular polygons from the triangle to the 16-gon in his 1525 treatise Underweysung der Messung mit dem Zirckel und Richtscheyt, intended for practical measurement in art and architecture.[22] One notable dissection rearranges the dodecagon into two congruent equilateral triangles, as shown in Freese's construction, which involves strategic cuts along diagonals and sides to form pieces that assemble into the target shape without overlap or gap.[23] For dissections into squares, Harry Lindgren's 1951 method achieves a minimal rearrangement into a single square using 6 pieces, though alternative configurations exist with 8 pieces, such as Freese's variant; these typically begin with cuts from vertices to intersection points on shorter diagonals, followed by subdividing peripheral regions to enable reassembly.[24][25] In Kürschák's tiling, a regular dodecagon inscribed in a unit circle is tiled by 12 equilateral triangles and 24 isosceles triangles with angles 15°-15°-150°, often achieved by combining pairs of isosceles triangles into rhombi on a grid; this relates the dodecagon's area to that of a circumscribing square.[26] Computational approaches to polygonal dissections draw from extensions of Hilbert's third problem in two dimensions, leveraging the Bolyai-Gerwien theorem to guarantee finite-piece rearrangements between equal-area polygons like the dodecagon and simpler shapes; algorithms optimize cut patterns by triangulating boundaries and matching edge lengths iteratively.[27] These methods preserve area throughout the process.Diagonals and Apothem

In a regular dodecagon with side length , the total number of diagonals is 54, determined by the formula where .[16] These diagonals connect non-adjacent vertices and fall into five distinct length classes based on the number of vertices skipped (from 1 to 5), corresponding to central angles of 60°, 90°, 120°, 150°, and 180°. The lengths are given by the general formula for the -th diagonal for , where yields the shortest diagonal and the longest (the diameter).[16] The exact lengths, simplified using trigonometric identities, are as follows:| Span | Description | Length Expression |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Shortest diagonal | |

| 3 | Second shortest | |

| 4 | Third | |

| 5 | Second longest | |

| 6 | Longest (diameter) |