Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Acquis communautaire

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

The Community acquis[1] or acquis communautaire (/ˈækiː kəˈmjuːnətɛər/; French: [aˌki kɔmynoˈtɛːʁ]),[2] sometimes called the EU acquis, and often shortened to acquis,[2] is the accumulated legislation, legal acts and court decisions that constitute the body of European Union law. The term is French, "acquis" meaning "that which has been acquired or obtained", and “communautaire” meaning "of the community".[3]

Chapters

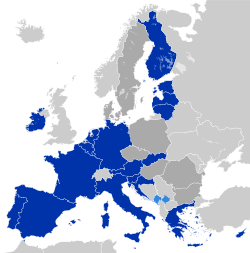

[edit]During the process of the enlargement of the European Union, the acquis was divided into 31 chapters for the purpose of negotiation between the EU and the candidate states for membership for the fifth enlargement (the ten that joined in 2004 plus Romania and Bulgaria which joined in 2007).[4] These chapters were:

- Free movement of goods

- Free movement of persons

- Freedom to provide services

- Free movement of capital

- Company law

- Competition policy

- Agriculture

- Fisheries

- Transport policy

- Taxation

- Economic and Monetary Union

- Statistics

- Social policy and employment

- Energy

- Industrial policy

- Small and medium-sized enterprises

- Science and research

- Education and training

- Telecommunication and information technologies

- Culture and audio-visual policy

- Regional policy and co-ordination of structural instruments

- Environment

- Consumers and health protection

- Cooperation in the field of Justice and Home Affairs

- Customs union

- External relations

- Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP)

- Financial control

- Financial and budgetary provisions

- Institutions

- Others

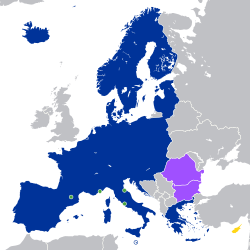

Beginning with the negotiations with Croatia (which joined in 2013), the acquis is split up into 35 chapters instead, with the purpose of better balancing between the chapters:[citation needed] (dividing the most difficult ones into separate chapters for easier negotiation, uniting some easier chapters, moving some policies between chapters, as well as renaming a few of them in the process)

- Free movement of goods

- Freedom of movement for workers

- Right of establishment and freedom to provide services

- Free movement of capital

- Public procurement

- Company law

- Intellectual property law

- Competition policy

- Financial services

- Information society and media

- Agriculture and rural development

- Food safety, veterinary and phytosanitary policy

- Fisheries

- Transport policy

- Energy

- Taxation

- Economic and monetary policy

- Statistics

- Social policy and employment (including anti-discrimination and equal opportunities for women and men)

- Enterprise and industrial policy

- Trans-European networks

- Regional policy and co-ordination of structural instruments

- Judiciary and fundamental rights

- Justice, freedom and security

- Science and research

- Education and culture

- Environment

- Consumer and health protection

- Customs union

- External relations

- Foreign, security and defence policy

- Financial control

- Financial and budgetary provisions

- Institutions

- Other issues

Correspondence between chapters of the 5th and the 6th Enlargement:[citation needed]

| 5th Enlargement | 6th Enlargement |

|---|---|

| 1. Free movement of goods | 1. Free movement of goods |

| 7. Intellectual property law | |

| 2. Free movement of persons | 2. Freedom of movement for workers |

| 3. Right of establishment and freedom to provide services | |

| 3. Freedom to provide services | |

| 9. Financial services | |

| 4. Free movement of capital | 4. Free movement of capital |

| 5. Company law | 6. Company law |

| 6. Competition policy | 8. Competition policy |

| 5. Public procurement | |

| 7. Agriculture | 11. Agriculture and rural development |

| 12. Food safety, veterinary and phytosanitary policy | |

| 8. Fisheries | 13. Fisheries |

| 9. Transport policy | 14. Transport policy |

| 21. Trans-European networks (one half of it) | |

| 10. Taxation | 16. Taxation |

| 11. Economic and Monetary Union | 17. Economic and monetary policy |

| 12. Statistics | 18. Statistics |

| 13. Social policy and employment | 19. Social policy and employment (including anti-discrimination and equal opportunities for women and men) |

| 14. Energy | 15. Energy |

| 21. Trans-European networks (one half of it) | |

| 15. Industrial policy | 20. Enterprise and industrial policy |

| 16. Small and medium-sized enterprises | |

| 17. Science and research | 25. Science and research |

| 18. Education and training | 26. Education and culture 10. Information society and media |

| 19. Telecommunication and information technologies | |

| 20. Culture and audio-visual policy | |

| 21. Regional policy and co-ordination of structural instruments | 22. Regional policy and co-ordination of structural instruments |

| 22. Environment | 27. Environment |

| 23. Consumer and health protection | 28. Consumer and health protection |

| 24. Cooperation in the field of Justice and Home Affairs | 23. Judiciary and fundamental rights |

| 24. Justice, freedom and security | |

| 25. Customs union | 29. Customs union |

| 26. External relations | 30. External relations |

| 27. Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) | 31. Foreign, security and defence policy |

| 28. Financial control | 32. Financial control |

| 29. Financial and budgetary provisions | 33. Financial and budgetary provisions |

| 30. Institutions | 34. Institutions |

| 31. Others | 35. Other issues |

Such negotiations usually involved agreeing transitional periods before new member states needed to implement the laws of the European Union fully and before they and their citizens acquired full rights under the acquis.

Terminology

[edit]The term acquis is also used to describe laws adopted under the Schengen Agreement, prior to its integration into the European Union legal order by the Treaty of Amsterdam, in which case one speaks of the Schengen acquis.[2][5][6] In relation to consumer law and consumer protection, the phrase "consumer acquis" is also used.[7]

The term acquis has been borrowed by the World Trade Organization Appellate Body, in the case Japan – Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages, to refer to the accumulation of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and WTO law ("acquis gattien"), though this usage is not well established.[citation needed]

It has been used to describe the achievements of the Council of Europe (an international organisation unconnected with the European Union):[8]

The Council of Europe's acquis in standard setting activities in the fields of democracy, the rule of law and fundamental human rights and freedoms should be considered as milestones towards the European political project, and the European Court of Human Rights should be recognised as the pre-eminent judicial pillar of any future architecture.

It has also been applied to the body of "principles, norms and commitments" of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE):[9]

Another question under debate has been how the Partners and others could implement the OSCE acquis, in other words its principles, norms, and commitments on a voluntary basis.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) introduced the concept of the OECD Acquis in its "Strategy for enlargement and outreach", May 2004.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "EuroVoc: Community acquis". Eurovoc.europa.eu. 11 July 2024. Archived from the original on 18 July 2024. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Collins English Dictionary. "acquis communautaire". Collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ Rudolf, Uwe Jens; Berg, Warren G. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Malta. Scarecrow Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780810873902.

- ^ "Chapters of the acquis - European Commission". neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu. 6 June 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Acquis - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ "Acquis Communautaire / Community Acquis – westernbalkans-infohub.eu". 31 January 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Jansen, N. and Zimmermann, R. (2018), Commentaries on European Contract Laws, Preface, Oxford: Oxford University Press, accessed on 8 August 2025

- ^ Section 12, Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe Resolution 1290

- ^ Intervention by Ambassador Aleksi Härkönen, Permanent Representative of Finland to the OSCE Archived 16 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine, Annual Security Review Conference.

- ^ "ANNEX 1: THE CONCEPT OF THE OECD "ACQUIS": A NOTE BY THE DIRECTORATE FOR LEGAL AFFAIRS" (PDF). Oecd.org. p. 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

External links

[edit]- EUR-Lex: European Union Law.

- JRC-Acquis, Aligned multilingual parallel corpus: 23,000 Acquis-related texts per language, available in 22 languages. Total size: 1 Billion words.

- Translation Memory of the EU-Acquis: Up to 1 Million translation units each, for 231 language pairs.

Acquis communautaire

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Conceptual Foundations

Etymology and Historical Origins

The term acquis communautaire originates from French, with acquis denoting "that which has been acquired" or "accumulated achievements," and communautaire referring to matters pertaining to a community, collectively signifying the body of law and practices attained by the European Community.[5] This linguistic formulation reflects the term's 20th-century coinage within the institutional lexicon of European integration, emphasizing an evolving corpus rather than a static code.[6] The underlying principle of the acquis traces to the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) via the Treaty of Rome, signed on 25 March 1957 and entering into force on 1 January 1958, which stipulated that future members must adhere to existing treaties, decisions, and acts adopted by EEC institutions without renegotiation.[3] This foundational requirement ensured continuity and irreversibility in integration, predating the term's formal usage by embedding the notion of an inviolable legal heritage in Article 237 of the Treaty, which governed accessions. The concept crystallized in practice during the 1960s amid stalled enlargement efforts, particularly following the UK's initial application in 1961 and the subsequent vetoes by France in 1963 and 1967, where discussions highlighted the non-negotiable nature of accumulated Community obligations.[6] The phrase acquis communautaire itself emerged prominently in the late 1960s during preparations for the EEC's first enlargement, specifically in accession negotiations with Denmark, Ireland, Norway, and the United Kingdom from 1969 to 1972, culminating in the 1973 accessions of Denmark, Ireland, and the UK (after Norway's referendum rejection).[3] European Commission documents from this period invoked the term to encapsulate the totality of treaties, legislation, jurisprudence, and international commitments that candidates were obligated to adopt, marking its transition from informal principle to codified expectation in enlargement policy. This usage underscored the acquis as a dynamic yet protected framework, resistant to dilution, and set precedents for subsequent expansions, such as Greece in 1981 and Iberian states in 1986.[6]Core Legal Definition and Scope

The acquis communautaire, commonly referred to as the acquis, constitutes the entirety of the European Union's legal order, encompassing the common rights and obligations binding upon all member states and integrated into their domestic legal systems.[1] This body of law derives its authority from the EU treaties and evolves dynamically through ongoing legislative, judicial, and interpretive developments, ensuring uniformity across the Union.[7] Unlike a static codex, the acquis is not enshrined in a single consolidated document but represents the accumulated patrimony of EU governance since the founding treaties.[3] In scope, the acquis extends to primary sources such as the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which establish the foundational principles and institutional framework.[8] It further includes secondary legislation—comprising regulations with direct effect, directives requiring transposition into national law, and decisions addressed to specific entities—as well as the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), which interprets and enforces these instruments.[3] International agreements concluded by the EU, general principles of law (such as proportionality and subsidiarity), and even non-binding elements like declarations and resolutions contribute to its breadth when they acquire legal force through practice or judicial recognition.[2] The acquis's scope is comprehensive and indivisible, obligating member states to accept it in full without opt-outs beyond those explicitly negotiated in treaties, as affirmed in provisions like Article 49 TEU, which conditions membership on respect for the Union's legal patrimony.[9] For enlargement, this entails alignment across approximately 35 policy chapters, covering areas from the internal market and competition to justice, foreign policy, and environmental standards, with an estimated volume exceeding 100,000 pages of legislative text as of the early 2000s, continually expanding.[10] This holistic application underscores the acquis's role in supranational integration, where national sovereignty yields to collective obligations for the maintenance of the single European market and policy coherence.[11]Distinction from National Law

The acquis communautaire, comprising the accumulated body of European Union (EU) law, differs fundamentally from national law in its supranational character and the principle of its primacy over conflicting domestic provisions. This principle dictates that, in areas of EU competence, national courts and authorities must prioritize EU law, setting aside any incompatible national legislation without requiring prior legislative amendment or annulment by national bodies.[12] The primacy ensures uniformity across member states, preventing fragmentation that would undermine the EU's legal order, and applies regardless of the timing or hierarchy of national laws.[13] The doctrine originated in the Court of Justice of the European Union's (CJEU) judgment in Costa v ENEL on 15 July 1964 (Case 6/64), where an Italian citizen challenged the nationalization of electricity under a law conflicting with prior Treaty of Rome obligations. The CJEU ruled that the treaty had instituted a "new legal order" for the benefit of the Community, in which member states irrevocably transferred sovereignty, rendering subsequent national measures incapable of overriding earlier EU commitments.[14] This judge-made principle, absent from the original treaties, was later affirmed in Declaration No 17 annexed to the Treaty of Lisbon (2009), which references CJEU case law as the basis for EU law's precedence under specified conditions.[12] In practice, this distinction obliges member states to interpret national law compatibly with the acquis where possible and to disapply it otherwise, as reinforced in subsequent rulings like Simmenthal (1978), extending primacy to all sources of EU law against any national norm.[13] For candidate countries, accepting the acquis during accession—without opt-outs beyond negotiated transitional arrangements—entails subordinating national legal systems to this hierarchy upon membership, ensuring no persistent derogations that could erode EU primacy.[15] While some national constitutional courts, such as Germany's Federal Constitutional Court, have occasionally asserted limits tied to ultra vires acts or identity cores, the CJEU maintains that such reservations cannot negate the acquis's binding supremacy in integrated fields.[16]Components and Structure

Primary Sources: Treaties and Founding Documents

The primary sources of the acquis communautaire comprise the founding and amending treaties that establish the constitutional framework of the European Union, serving as the bedrock of its primary law. These treaties outline the objectives, institutions, decision-making processes, and principles governing the EU, requiring full acceptance by member states without derogation except as explicitly permitted.[17] [18] The inaugural treaty was the Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), signed on 18 April 1951 in Paris by Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, and entering into force on 23 July 1952. This 100-article agreement created a supranational authority to manage a common market for coal and steel, aiming to foster economic expansion, employment growth, and modernization while preventing conflict through resource pooling. The ECSC Treaty expired on 23 July 2002, with its functions integrated into the broader EU framework, but its principles remain embedded in the acquis.[19] [20] Subsequent foundational documents include the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC) and the Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), both signed on 25 March 1957 in Rome and entering into force on 1 January 1958. The EEC Treaty laid the groundwork for a customs union and common market, emphasizing free movement of goods, persons, services, and capital, while the Euratom Treaty focused on coordinated nuclear research and development among the same six states. These Rome Treaties expanded supranational integration beyond heavy industry.[21] [17] Later amendments consolidated and evolved this primary law. The Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty), signed on 7 February 1992 and effective from 1 November 1993, introduced the three-pillar structure, European citizenship, and the euro currency framework. Further modifications via the Treaty of Amsterdam (1997, effective 1999), Treaty of Nice (2001, effective 2003), and Treaty of Lisbon (2007, effective 1 December 2009) reformed institutions, enhanced qualified majority voting, and streamlined the legal order into the current Treaty on European Union (TEU) and Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), alongside the enduring Euratom Treaty. Accession treaties for new members incorporate these consolidated texts, ensuring the acquis's uniformity.[21] [22]Secondary Sources: Legislation and Regulations

Secondary legislation constitutes the primary operational component of the acquis communautaire, comprising binding acts adopted by EU institutions under powers delegated by the treaties, as outlined in Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). These acts—regulations, directives, and decisions—implement and flesh out the general principles established in primary law, covering policy areas from the internal market to environmental protection and justice.[23] Unlike treaties, secondary legislation is dynamic and voluminous, with over 20,000 regulations and directives in force as of 2023, subject to ongoing revision and repeal to reflect evolving priorities.[2] Regulations are legislative acts of general application, fully binding on all Member States in their entirety and directly applicable without requiring national transposition, ensuring uniform implementation across the EU. For instance, Regulation (EU) No 2016/679, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), entered into force on May 25, 2018, and applies directly to data controllers and processors EU-wide, exemplifying how regulations enforce harmonized standards in the acquis. Adopted typically via the ordinary legislative procedure involving the European Parliament and Council on Commission proposals, regulations dominate areas needing consistency, such as competition policy and trade.[24] Directives, by contrast, bind Member States to achieve specified results while affording discretion over the form and methods of implementation, facilitating approximation of national laws to EU objectives without full uniformity. Under Article 288 TFEU, directives must be transposed into domestic legislation within set deadlines, as seen in Directive 2008/50/EC on ambient air quality, adopted June 21, 2008, which requires Member States to set national emission limits but permits variation in enforcement mechanisms. This instrument is prevalent in harmonization chapters of the acquis, such as consumer protection and social policy, where diverse national contexts demand flexibility; non-transposition can trigger infringement proceedings by the Commission.[24] Decisions serve as individualized binding measures addressed to specific recipients—Member States, EU institutions, or private entities—lacking the general scope of regulations or directives but integral to targeted enforcement within the acquis. For example, Commission Decision 2010/15/EU of December 8, 2009, authorized state aid in specific cases, directly obligating the addressee without broader applicability. In accession contexts, candidate states must align with the corpus of such decisions relevant to their negotiations, particularly in areas like state aid control and fisheries quotas. Collectively, these instruments form the enforceable core of the acquis, screened during enlargement via 35 policy chapters, where full adoption is mandatory barring negotiated transitional arrangements justified by administrative capacity.[24][25]Supplementary Elements: Case Law and Soft Law

The case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) constitutes a supplementary element of the acquis communautaire, providing authoritative interpretations of primary and secondary EU law that bind member states and institutions.[2] This jurisprudence derives general principles from the treaties, such as direct effect established in Van Gend en Loos v Netherlands Inland Revenue Administration (Case 26/62, 1963), which affirmed that certain EU provisions confer rights enforceable by individuals in national courts, and supremacy articulated in Costa v ENEL (Case 6/64, 1964), prioritizing EU law over conflicting national measures.[15] In the context of EU enlargement, candidate states must align with this body of precedents, as the acquis encompasses unwritten law shaped by CJEU rulings that evolve through ongoing adjudication.[2] CJEU decisions expand the effective scope of the acquis by clarifying ambiguities in legislation; for instance, in Coman and Others v Inspectoratul General pentru Imigrări (Case C-673/16, 2018), the Court extended free movement rights under Directive 2004/38/EC to same-sex spouses, interpreting "spouse" inclusively despite varying national definitions, thereby integrating such rulings into the cumulative obligations of the acquis.[26] These judgments ensure uniform application across the Union but have drawn scrutiny for potentially overriding national constitutional traditions without explicit treaty basis, as evidenced in debates over the Court's expansive role in areas like criminal law interpretation.[27] Soft law instruments form another supplementary layer of the acquis, comprising non-binding measures such as Commission guidelines, recommendations, and communications that guide the interpretation and practical implementation of binding law without formal legal force.[2] Adopted since the 1960s, these tools—exemplified by early Commission notices on competition policy—influence member state behavior by expressing EU principles, fostering compliance through legitimate expectations, and serving as interpretive aids in CJEU proceedings.[28] In enlargement processes, soft law elements, including subsidy guidelines and policy frameworks, must be respected by candidates, as they embed evolving standards into the acquis despite lacking enforceability akin to regulations or directives.[29] Though not directly enforceable, soft law acquires practical effects by shaping national legislation, informing CJEU assessments of proportionality, and integrating into the acquis as part of the Union's policy objectives, particularly in dynamic fields like return migration where swift adoption circumvents lengthy legislative delays.[30] Critics note that over-reliance on such instruments can blur accountability, as unelected Commission officials exert influence without parliamentary oversight, yet empirical data from accession negotiations shows their role in harmonizing practices across diverse legal traditions.[31]Role in EU Integration and Enlargement

Application in Accession Negotiations

In the accession negotiations for European Union membership, the acquis communautaire forms the foundational structure, divided into 35 policy chapters that candidate countries must progressively align with through transposition, implementation, and enforcement.[25] These chapters cover areas such as free movement of goods (Chapter 1), judiciary and fundamental rights (Chapter 23), and financial and budgetary provisions (Chapter 33), ensuring comprehensive coverage of EU law, principles, and practices.[25] Negotiations typically commence after the European Council adopts a negotiating framework, following a Commission's opinion on the candidate's application, with unanimous approval from all member states required to open talks.[32] The process begins with an analytical screening phase for each chapter, during which the Commission explains relevant acquis elements and the candidate assesses its national laws for compatibility, often identifying gaps in administrative capacity or legislative alignment.[33] Provisional closure of a chapter occurs only when the candidate demonstrates sufficient progress in meeting commitments, including benchmarks for ongoing reforms, and the EU verifies effective implementation rather than mere adoption.[32] This chapter-based approach, formalized since the 1990s enlargements, enforces the Copenhagen criteria's requirement that candidates possess the "ability to take on the obligations of membership," interpreted as full and irreversible compliance with the acquis by the accession date, subject to limited transitional arrangements negotiated case-by-case.[34][35] Recent adaptations, such as the 2022 revised enlargement methodology for Western Balkan candidates, introduce six thematic clusters grouping chapters (e.g., fundamentals cluster including rule of law) to prioritize early progress in core areas like democracy and economic governance before advancing to others.[36] This clustering aims to address implementation deficits observed in prior accessions, such as incomplete judicial reforms in Romania and Bulgaria post-2007, by linking cluster openings and closures to verifiable outcomes.[32] For instance, negotiations with Ukraine and Moldova, opened on June 25, 2024, apply this framework amid geopolitical pressures, requiring accelerated alignment despite ongoing conflicts.[37] Overall, the acquis's application tests not just legal transposition but institutional readiness, with the Commission monitoring via annual progress reports to mitigate risks of post-accession backsliding.[25]Adoption Requirements for Candidate States

Candidate states seeking European Union membership are required to adopt the entire acquis communautaire, comprising the accumulated body of EU law, principles, and obligations, as a fundamental precondition for accession.[7] This adoption entails not only formal acceptance but also transposition into national legislation, effective implementation, and enforcement through adequate administrative and judicial capacities.[38] Failure to demonstrate credible progress in these areas can halt negotiations or lead to their reversal under the revised enlargement methodology introduced in 2020.[39] The adoption process is embedded within accession negotiations, governed by Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union, which stipulates that candidates must respect EU values and align with membership obligations.[34] Central to this are the Copenhagen criteria established in 1993, requiring stability of democratic institutions, a functioning market economy capable of withstanding competitive pressures, and the ability to assume the obligations of membership—including full adherence to the acquis.[7] Candidates prepare National Programmes for the Adoption of the Acquis (NPAA) to outline timelines and strategies for alignment, supported by pre-accession financial instruments such as the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA).[7] Negotiations proceed through an analytical screening of the candidate's legislation against the acquis, divided into 35 chapters corresponding to policy fields like free movement of goods, judiciary and fundamental rights, and competition policy.[38] Under the 2020 methodology, chapters are grouped into six thematic clusters, with priority on "fundamentals" (clusters covering rule of law, Chapters 23 and 24), emphasizing early progress and interim benchmarks before advancing.[39] Each chapter opens only after the candidate meets specific benchmarks, submits negotiating positions, and receives EU common positions; closure requires unanimous satisfaction from EU member states, verified by the European Commission's assessments of legislative alignment and practical implementation.[38] Adoption extends beyond legal transposition to building institutional frameworks for ongoing compliance, as the acquis evolves post-accession.[7] Candidates must demonstrate irreversible reforms, particularly in sensitive areas like anti-corruption and judicial independence, with the EU retaining the right to suspend negotiations if backsliding occurs, enhancing conditionality and dynamism in the process.[39] Successful closure of all chapters culminates in an accession treaty, but provisional closure does not imply permanent acceptance, as the EU verifies final alignment before signature.[38]Transitional Periods and Exceptions

Transitional periods in the context of the acquis communautaire refer to time-limited derogations negotiated during EU accession processes, permitting new member states delayed or phased implementation of specific acquis elements to accommodate economic, administrative, or social adjustment challenges. These arrangements are enshrined in accession treaties and apply asymmetrically, often protecting existing member states' interests while allowing candidates gradual alignment. For instance, the 2003 Act of Accession for the 2004 enlargement (covering Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia) incorporated transitional measures across 31 negotiation chapters, including up to seven years for full free movement of workers, during which pre-2004 members could impose labor market restrictions on nationals from new states.[40][41] Such periods have been common in enlargements to mitigate disruptions, particularly in sensitive sectors like agriculture and fisheries. In the 1986 accession of Spain and Portugal, transitional arrangements spanned up to ten years for agricultural market organization and industrial restructuring, enabling gradual integration of these economies into the Common Agricultural Policy without immediate fiscal strain on the EU budget.[42] Similarly, the 2004 enlargement featured phased direct payments to farmers in new states, reaching full parity by 2013, alongside temporary limits on land acquisition by non-nationals to safeguard rural economies.[43] These measures underscore the pragmatic balancing in enlargement, where full acquis adoption remains the endpoint, but short-term flexibility facilitates political consensus among member states. Exceptions, rarer than transitional periods, involve permanent or semi-permanent derogations from acquis provisions, typically justified by unique national circumstances and subject to strict EU oversight. The 2003 Accession Treaty granted Bulgaria and Romania—joining in 2007—extended safeguards, including cooperation mechanisms for judicial reform and anti-corruption until 2009, with potential prolongation if compliance lagged.[44] In taxation, new members have secured temporary deviations from VAT and excise rules to align fiscal systems, as outlined in accession protocols, though direct taxation largely escapes harmonization due to subsidiarity principles.[45] Critics, including some economists, argue these arrangements can entrench disparities or delay benefits like labor mobility, yet empirical data from post-2004 migration flows indicate net economic gains for host states despite initial restrictions.[46] Overall, transitional periods and exceptions remain bounded by the Copenhagen criteria, ensuring eventual conformity without undermining the acquis's uniformity.Historical Evolution

Early Development (1950s–1980s)

The acquis communautaire, the accumulated body of European Community law, originated with the Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), signed on 18 April 1951 and entering into force on 23 July 1952 among Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.[47] This treaty created the first supranational legal framework, including High Authority decisions, Council recommendations, and provisions for joint management of coal and steel production to foster economic interdependence and avert conflict.[47] It established core principles such as supranational decision-making and enforcement mechanisms, forming the initial nucleus of Community law that later applicants would need to adopt.[2] The Treaties of Rome, signed on 25 March 1957 and effective from 1 January 1958, significantly expanded the acquis by instituting the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom).[47] The EEC Treaty laid foundational rules for a common market, mandating free movement of goods, persons, services, and capital; establishing the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) through regulations adopted in 1962; and introducing competition rules under Articles 85–94 (now 101–109 TFEU).[47] Secondary legislation proliferated in the 1960s, with the Council issuing directives and regulations on harmonization, while the European Court of Justice's rulings, such as Van Gend en Loos (1963), affirmed direct effect and supremacy of Community law, embedding these doctrines into the acquis.[2] The 1965 Merger Treaty unified the executives of the ECSC, EEC, and Euratom, streamlining institutional law and facilitating further normative growth.[47] The concept of the acquis as an immutable heritage requiring full acceptance by acceding states crystallized during preparations for the first enlargement. In its 1972 opinion on Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom's applications, the European Commission delineated the acquis as encompassing treaties, legislation, Court jurisprudence, and principles of direct applicability, insisting on no fundamental renegotiation.[2] These countries joined on 1 January 1973, expanding membership to nine and testing the acquis's application, with over 1,500 pieces of secondary law in force by then, primarily in agriculture, trade, and competition.[2] Greece's accession in 1981 reinforced this, as the Commission's 1979 opinion extended the acquis to include democratic stability and human rights criteria, amid transitional arrangements for its economy.[2] By the mid-1980s, the acquis had ballooned through directives on environmental and social policies, setting precedents for future harmonization without altering core commitments.[2]Post-Cold War Enlargements (1990s–2000s)

The dissolution of communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 prompted the European Union to initiate association agreements, known as Europe Agreements, with countries including Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, laying groundwork for future accession while requiring progressive alignment with the acquis communautaire.[43] These agreements, signed between 1991 and 1996, mandated the gradual adoption of EU norms in trade, competition, and intellectual property to foster market economies capable of withstanding competitive pressures.[43] The Copenhagen European Council in June 1993 formalized accession criteria, emphasizing that candidate states must possess stable institutions guaranteeing democracy, a functioning market economy, and the capacity to adopt and implement the acquis communautaire in full.[7] This "acquis criterion" encompassed the entire body of EU law, including treaties, regulations, directives, and jurisprudence, estimated at over 80,000 pages by the late 1990s, necessitating comprehensive transposition into national legal systems.[48] To support this process, the EU launched the PHARE program in 1989, providing technical assistance and funding—totaling around €15 billion by 2004—for institution-building and legal harmonization in candidate states.[49] Accession negotiations for Central and Eastern European candidates opened in March 1998, structured around 31 chapters covering policy areas such as internal market, agriculture, and justice, with each requiring screening of national laws against acquis standards and commitments to full implementation upon entry.[50] By 2002, negotiations concluded with 10 countries—Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia—agreeing to adopt the acquis subject to transitional periods in sensitive sectors like free movement of persons (up to seven years) and agricultural subsidies to mitigate fiscal strains on EU budgets.[48] These enlargements, effective May 1, 2004, for the 10 states and January 1, 2007, for Bulgaria and Romania, doubled the EU's population to nearly 500 million while imposing safeguard clauses allowing temporary derogations if implementation faltered.[51] Candidate states faced significant hurdles in acquis adoption, including underdeveloped administrative capacities, entrenched corruption, and the need for over 100,000 legislative acts in some cases, often leading to uneven enforcement despite formal transposition.[52] For instance, environmental and competition chapters proved particularly demanding, requiring costly infrastructure investments and antitrust reforms amid economic transitions from central planning.[53] The EU monitored progress through regular reports, imposing conditionality that delayed closure of chapters until benchmarks were met, though critics noted that political momentum for enlargement sometimes prioritized speed over depth of reform.[54]Contemporary Challenges (2010s–Present)

In the 2010s, EU enlargement efforts faced significant stagnation, particularly in the Western Balkans, where candidate countries struggled to implement the acquis communautaire amid stalled political and economic reforms. Croatia's accession in 2013 marked the last successful enlargement, but subsequent processes for Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia encountered obstacles including weak rule of law, corruption, and ethnic tensions, leading to minimal progress in closing negotiating chapters.[55] Internal EU divisions exacerbated these issues, as evidenced by France's veto in October 2019 against opening accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia, citing deficiencies in the EU's absorption capacity and the need for internal reforms before further expansion.[56] The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 prompted accelerated accession bids from Ukraine and Moldova, granted candidate status in June 2022, yet these highlighted acute challenges in aligning with the acquis under wartime conditions. Ukraine's application emphasized geopolitical urgency, but experts note substantial gaps in adopting over 35 chapters of the acquis, particularly in judiciary reform, anti-corruption measures, and economic alignment, compounded by the destruction of infrastructure and displacement of millions.[57] Similarly, enlargement to conflict-affected states raises fiscal and security risks for the EU, including potential net budgetary costs exceeding €100 billion annually for Ukraine alone due to reconstruction needs and agricultural competition impacts on existing members.[58] Parallel internal challenges emerged from non-compliance with acquis elements by existing members Hungary and Poland, prompting the EU to introduce rule of law conditionality in December 2020 via Regulation (EU) 2020/2092, allowing suspension of funds for breaches affecting the EU budget, such as judicial independence violations. The European Commission triggered the mechanism against Hungary in April 2022 and Poland in 2022, citing systemic rule of law deficiencies that undermined effective management of EU funds, including over €6 billion suspended from Hungary by December 2022.[59] Hungary and Poland contested the regulation before the Court of Justice of the EU, arguing it violated competences and Treaty principles, but the Court dismissed their actions on February 16, 2022, affirming its alignment with EU law to protect financial interests.[60] This enforcement tool underscores the acquis's vulnerability to backsliding post-accession, as both countries faced over 100 infringement proceedings related to judicial reforms conflicting with acquis Chapter 23 on judiciary and fundamental rights.[61] These developments reveal broader tensions in the acquis framework, including the need for stricter pre-accession enforcement and adaptations to new policy areas like digital regulation and climate goals under the European Green Deal, where candidates face high implementation costs relative to GDP—estimated at 1-2% annually for Western Balkan states.[44] EU leaders have responded with proposals for "gradual integration" models, allowing partial acquis adoption before full membership to mitigate risks, though consensus remains elusive amid member state divergences on enlargement pace.[62]Criticisms and Sovereignty Implications

Eurosceptic Critiques on National Autonomy

Eurosceptics argue that the acquis communautaire compels member states to surrender substantial elements of national sovereignty, as it requires the wholesale adoption of over 35 chapters encompassing approximately 100,000 pages of binding regulations, directives, and jurisprudence that evolve without national veto power.[63] This body of law, enforced through the principle of direct effect and primacy—affirmed by the European Court of Justice in the 1964 Costa v ENEL ruling—overrides conflicting domestic legislation, rendering national parliaments effectively powerless to repeal or diverge from EU-derived rules in covered domains such as trade, agriculture, and environmental policy.[64] Critics maintain this creates a one-way ratchet of integration, where states pool authority in Brussels but retain no equivalent mechanism to reclaim it, leading to policy lock-in that prioritizes supranational uniformity over national democratic preferences.[65] In the context of Brexit, proponents of withdrawal, including figures associated with the Vote Leave campaign, highlighted the acquis as a core impediment to British autonomy, asserting that subjection to its regulatory framework—spanning immigration controls, fishing rights, and financial services—prevented the UK from forging independent global trade deals or tailoring laws to domestic needs.[66] The 2016 referendum, which passed with 51.9% support for leaving on June 23, was framed as a restoration of parliamentary sovereignty, with post-exit divergence from the acquis (such as the 2021 repeal of certain EU-derived VAT rules) cited as evidence of regained control, though implementation has involved transitional alignments under the 2020 Trade and Cooperation Agreement.[67] Eurosceptics contend that without exit, the acquis's dynamic expansion—adding thousands of new measures annually via qualified majority voting—would perpetuate this erosion, as national opt-outs remain rare and temporary.[68] Central and Eastern European leaders, such as Hungary's Viktor Orbán, have voiced parallel concerns, portraying the acquis as an instrument for ideological overreach that undermines constitutional sovereignty in non-economic spheres like judicial independence and family policy.[63] Orbán's government, facing EU infringement proceedings since 2018 over media and judiciary reforms deemed incompatible with acquis-derived rule-of-law standards, argues that enforcement via funding conditionality (e.g., the 2022 withholding of €22 billion from Hungary) exemplifies federalist encroachment, prioritizing Brussels' interpretive monopoly over national self-determination.[69] Similarly, Poland's former Law and Justice administration criticized the acquis for imposing uniform standards that conflict with cultural specifics, as seen in 2021 clashes over judicial appointments, where Warsaw asserted primacy of its 1997 Constitution.[63] These critiques underscore a broader Eurosceptic narrative that the acquis, while ostensibly market-oriented, facilitates creeping competence expansion into sovereignty-sensitive areas, with limited empirical recourse for dissenting states beyond litigation or fiscal penalties.[70]Economic and Administrative Burdens

The adoption of the acquis communautaire entails substantial economic costs for candidate states, primarily through mandatory investments in infrastructure, environmental protection, and regulatory upgrades to align with EU standards. For instance, in Central and Eastern European countries during the 2004 enlargement, compliance with environmental directives required expenditures equivalent to 1-2% of annual GDP in the initial years, focusing on wastewater treatment, air quality controls, and waste management facilities.[53] Similarly, for Western Balkan candidates, full alignment is projected to demand billions in investments, with EU pre-accession funds like the €6 billion Reform and Growth Facility (2024-2027) covering only a fraction, leaving national budgets to absorb the majority through public spending or private sector outlays.[71] These costs arise from the need to retrofit industries and agriculture to meet competition policy, phytosanitary rules, and single market norms, often straining fiscal resources in economies with lower per capita incomes.[72] Regulatory compliance under the acquis imposes ongoing economic burdens on businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which dominate employment in many candidate and new member states. EU rules on product standards, labor protections, and sustainability reporting elevate operational costs, with surveys indicating that over 60% of EU companies, including those in post-accession states, view such regulations as barriers to investment and growth.[73] In new members like those from the 2004 cohort, the transposition of directives has led to higher administrative overheads for SMEs, reducing competitiveness against more established EU firms and contributing to slower productivity gains in regulated sectors.[74] Critics, including analyses from libertarian-leaning think tanks, argue that this regulatory framework curtails economic flexibility, locking countries into a "regulatory state" model that hampers innovation and favors larger incumbents over dynamic small-scale operators.[74] Administrative burdens compound these challenges, necessitating extensive institutional reforms to enforce the acquis, such as establishing independent regulatory agencies, judiciary enhancements, and civil service training programs. Candidate states must allocate resources to build administrative capacity, often diverting funds from core services; for example, alignment in areas like state aid control and public procurement requires specialized expertise that many lack, leading to prolonged transitional periods and enforcement gaps.[75] In the Western Balkans, ongoing efforts to streamline processes highlight persistent overload, with EU reports noting deficiencies in regulatory impact assessments that exacerbate burdens on public administrations and private compliance.[76] Eurosceptic perspectives emphasize that these demands erode national policy autonomy, imposing a uniform bureaucratic layer ill-suited to diverse economic contexts and fostering dependency on EU technical assistance rather than organic development.[77] While EU financial instruments mitigate some upfront costs, empirical assessments indicate that candidate countries shoulder the bulk of adaptation expenses, with net transfers representing less than 1% of GDP annually and insufficient to offset macro-financial strains from lost policy levers.[72] This has fueled debates on whether the acquis' rigidity undermines long-term growth potential, as evidenced by persistent SME complaints in new members about disproportionate compliance loads relative to benefits.[78]Democratic Deficit and Uniformity Impositions

The obligation imposed on candidate states to fully adopt the acquis communautaire—encompassing over 100,000 pages of EU legislation, regulations, and case law as of the early 2000s—without the option for substantive negotiation or derogation in core areas has drawn criticism for amplifying the EU's democratic deficit.[79] This take-it-or-leave-it approach requires national parliaments to transpose supranational rules into domestic law, often bypassing rigorous debate, as evidenced in the 2004 enlargement where Central and Eastern European legislatures used accelerated procedures to meet accession deadlines, limiting public and legislative input.[80] Critics argue this process transfers legislative authority from elected national bodies to unelected EU institutions like the Commission, which proposes much of the acquis, thereby diluting direct democratic accountability at the member-state level.[81] Uniformity impositions inherent in the acquis further exacerbate sovereignty concerns by mandating policy harmonization across disparate national contexts, such as uniform environmental standards or competition rules that may impose disproportionate burdens on smaller or less developed economies. For instance, during the 2004–2007 enlargements, new members from Central and Eastern Europe adopted the acquis as "empty shells," with formal compliance coexisting alongside informal practices due to inadequate adaptation, leading to implementation gaps and subsequent EU infringement proceedings against 10 of the 12 new states by 2010.[82] Eurosceptic analysts, including those from think tanks skeptical of over-centralization, contend that this enforced convergence prioritizes supranational coherence over national priorities, fostering resentment as voters perceive a loss of control over laws affecting daily governance, such as agricultural subsidies or labor regulations tailored to larger Western economies.[83] Empirical data underscores these tensions: post-accession surveys in Eastern member states revealed declining trust in EU institutions, correlating with perceptions of imposed uniformity, as national electorates lacked veto power over acquis updates post-membership, with qualified majority voting in the Council overriding individual objections in over 80 policy areas by 2020.[84] While pro-integration sources, often from EU-funded bodies, frame the acquis as essential for market functionality, independent assessments highlight causal links between rapid, unadapted adoption and populist backlashes, as seen in Hungary and Poland where resistance to uniformity framed EU rules as external diktats undermining sovereign decision-making.[85] This dynamic illustrates a broader critique that the acquis entrenches a technocratic model, where uniformity serves elite consensus but erodes the causal chain from voter preferences to policy outcomes.[70]Broader Impacts and Reception

Effects on Policy Harmonization

The acquis communautaire serves as the foundational mechanism for policy harmonization within the European Union by mandating that member states transpose EU directives into national law and directly apply regulations, ensuring a uniform baseline across diverse jurisdictions. This process, embedded in the EU's legal order since the Treaty of Rome in 1957, compels alignment in key policy domains such as the internal market, competition rules, and consumer protection, reducing discrepancies that could distort trade or investment. For instance, directives on product safety and liability, such as Directive 85/374 on liability for defective products, achieve complete harmonization of laws, regulations, and administrative provisions to facilitate cross-border commerce while upholding fundamental legal principles.[86] In practice, this harmonization manifests through systematic transposition efforts, where national legislatures adapt domestic frameworks to over 14,000 legal acts comprising the acquis as of 2002, a volume that has since expanded significantly with annual adoption of hundreds of new acts. Examples include the environmental acquis, which required Central and Eastern European candidate countries during the 2004 and 2007 enlargements to overhaul legislation, bridging substantial gaps in areas like pollution control and waste management to meet EU standards. Similarly, in copyright policy, eight directives enacted between 1991 and 2019 standardized exceptions, limitations, and enforcement across member states, enabling a cohesive digital single market but imposing transposition costs estimated in the billions of euros for compliance infrastructure.[87][88][89] The effects extend to fiscal and commercial policies, such as value-added tax (VAT) harmonization under the acquis, which sets minimum rates and administrative uniformity to prevent distortions in the single market, as evidenced by the 2006 VAT Directive updating prior frameworks. While this fosters predictability and economic integration—evidenced by the elimination of internal tariffs and mutual recognition principles—it also constrains national policy experimentation, as member states must maintain equivalence with evolving acquis elements, including judgments from the Court of Justice of the EU. Empirical assessments indicate that such convergence has streamlined regulatory compliance for businesses operating EU-wide, yet it correlates with increased administrative burdens, with transposition delays reported in up to 20% of directives annually in some periods.[90][91][89]| Policy Area | Key Harmonization Mechanism | Notable Example |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Market | Directives for mutual recognition | Directive 2001/29 on copyright in information society[89] |

| Environment | Acquis alignment in enlargements | Adoption of 300+ environmental directives by 2004 candidates[88] |

| Fiscal Policy | Minimum standards via directives | VAT Directive 2006/112/EC setting 15% minimum rate[90] |