Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mendelevium

View on Wikipedia| Mendelevium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass number | [258] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mendelevium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 101 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | f-block groups (no number) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | f-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 5f13 7s2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 31, 8, 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid (predicted) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1100 K (800 °C, 1500 °F) (predicted) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 10.3(7) g/cm3 (predicted)[1][a] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | common: +3 +2[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | synthetic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) (predicted)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-11-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

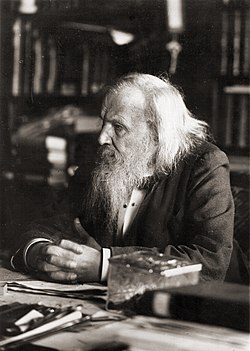

| Naming | after Dmitri Mendeleev | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (1955) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of mendelevium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mendelevium is a synthetic chemical element; it has symbol Md (formerly Mv) and atomic number 101. A metallic radioactive transuranium element in the actinide series, it is the first element by atomic number that currently cannot be produced in macroscopic quantities by neutron bombardment of lighter elements. It is the thirteenth actinide, the ninth transuranic element, and the first transfermium; it is named after Dmitri Mendeleev, the father of the periodic table.

Like all the transfermiums, it can only be produced in particle accelerators by bombarding lighter elements with charged particles. The element was first produced in 1955 by bombarding einsteinium with alpha particles, the method still used today. Using commonly-available microgram quantities of einsteinium-253, over a million mendelevium atoms may be made each hour. The chemistry of mendelevium is typical for the late actinides, with a dominant +3 oxidation state but also a +2 oxidation state accessible in solution. All known isotopes of mendelevium have short half-lives; there are currently no uses for it outside basic scientific research, and only small amounts are produced.

Discovery

[edit]

Mendelevium was the ninth transuranic element to be synthesized. It was first synthesized by Albert Ghiorso, Glenn T. Seaborg, Gregory Robert Choppin, Bernard G. Harvey, and team leader Stanley G. Thompson in early 1955 at the University of California, Berkeley. The team produced 256Md (half-life 77.7 minutes[4]) when they bombarded an 253Es target consisting of only a billion (109) einsteinium atoms with alpha particles (helium nuclei) in the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory's 60-inch cyclotron, thus increasing the target's atomic number by two. 256Md thus became the first isotope of any element to be synthesized one atom at a time. In total, seventeen mendelevium atoms were detected.[5] This discovery was part of a program, begun in 1952, that irradiated plutonium with neutrons to transmute it into heavier actinides.[6] This method was necessary because of a lack of known beta decaying isotopes of fermium that might allow production by neutron capture; it is now known that such production is impossible at any possible reactor flux due to the very short half-life to spontaneous fission of 258Fm[4] and subsequent isotopes, which still do not beta decay - the fermium gap that, as far as we know, sets a hard limit to the success of neutron capture processes.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

To predict if the production of mendelevium would be possible, the team made use of a rough calculation. The number of atoms that would be produced would be approximately equal to the product of the number of atoms of target material, the target's cross section, the ion beam intensity, and the time of bombardment; this last factor was related to the half-life of the product when bombarding for a time on the order of its half-life. This gave one atom per experiment. Thus under optimum conditions, the preparation of only one atom of element 101 per experiment could be expected. This calculation demonstrated that it was feasible to go ahead with the experiment.[5] The target material, einsteinium-253, could be produced readily from irradiating plutonium: one year of irradiation would give a billion atoms, and its three-week half-life meant that the element 101 experiments could be conducted in one week after the produced einsteinium was separated and purified to make the target. However, it was necessary to upgrade the cyclotron to obtain the needed intensity of 1014 alpha particles per second; Seaborg applied for the necessary funds.[6]

While Seaborg applied for funding, Harvey worked on the einsteinium target, while Thomson and Choppin focused on methods for chemical isolation. Choppin suggested using α-hydroxyisobutyric acid to separate the mendelevium atoms from those of the lighter actinides.[6] The initial separation was done by a recoil technique suggested by Albert Ghiorso: the einsteinium was placed on the opposite side of the target from the beam, so that the momentum of the recoiling mendelevium atoms would allow them to leave the target and be caught on a gold catcher foil behind it. This recoil target was made by an electroplating technique, developed by Alfred Chetham-Strode. This technique gave a very high yield, which was absolutely necessary when working with such a rare and valuable product as the einsteinium target material.[5] The recoil target consisted of 109 atoms of 253Es which were deposited electrolytically on a thin gold foil. It was bombarded by 41 MeV alpha particles in the Berkeley cyclotron with a very high beam density of 6×1013 particles per second over an area of 0.05 cm2. The target was cooled by water or liquid helium, and the foil could be replaced.[5][7]

Initial experiments were carried out in September 1954. No alpha decay was seen from mendelevium atoms; thus, Ghiorso suggested that the mendelevium had all decayed by electron capture to fermium-256, correctly believed to decay primarily by fission, and that the experiment should be repeated, this time searching for those spontaneous fission events. This version of the experiment was performed in February 1955.[6]

On the day of discovery, 19 February, alpha irradiation of the einsteinium target occurred in three three-hour sessions. The cyclotron was in the University of California campus, while the Radiation Laboratory was on the next hill. To deal with this situation, a complex procedure was used: Ghiorso took the catcher foils (there were three targets and three foils) from the cyclotron to Harvey, who would use aqua regia to dissolve it and pass it through an anion-exchange resin column to separate the transuranium elements from the gold and other products.[6][8] The resultant drops entered a test tube, which Choppin and Ghiorso took in a car to get to the Radiation Laboratory as soon as possible. Thompson and Choppin used a cation-exchange resin column and the α-hydroxyisobutyric acid. The solution drops were collected on platinum disks and dried under heat lamps. The three disks were expected to contain, respectively, the fermium, no new elements, and the mendelevium. Finally, they were placed in their own counters, which were connected to recorders such that spontaneous fission events would be recorded as huge deflections in a graph showing the number and time of the decays. There thus was no direct detection, but by observation of spontaneous fission events arising from its electron-capture daughter 256Fm. The first one was identified with a "hooray" followed by a "double hooray" and a "triple hooray". The fourth one eventually officially proved the chemical identification of the 101st element, mendelevium. In total, five decays were reported up until 4 a.m. Seaborg was notified and the team left to sleep.[6] Additional analysis and further experimentation showed the produced mendelevium isotope to have the expected mass of 256 and decay by electron capture to fermium-256 (half-life 157.6 minutes), the source of the observed fission.[4]

We thought it fitting that there be an element named for the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, who had developed the periodic table. In nearly all our experiments discovering transuranium elements, we'd depended on his method of predicting chemical properties based on the element's position in the table. But in the middle of the Cold War, naming an element for a Russian was a somewhat bold gesture that did not sit well with some American critics.[9]

— Glenn T. Seaborg

Being the first of the second hundred of the chemical elements, it was decided that the element would be named "mendelevium" after the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, father of the periodic table. Because this discovery came during the Cold War, Seaborg had to request permission from the government of the United States to propose that the element be named for a Russian, but it was granted.[6] The name "mendelevium" was accepted by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in 1955 with symbol "Mv",[10] which was changed to "Md" in the next IUPAC General Assembly (Paris, 1957).[11]

Characteristics

[edit]Physical

[edit]

In the periodic table, mendelevium is located to the right of the actinide fermium, to the left of the actinide nobelium, and below the lanthanide thulium. Mendelevium metal has not yet been prepared in bulk quantities, and bulk preparation is currently impossible.[13] Nevertheless, a number of predictions and some preliminary experimental results have been done regarding its properties.[13]

The lanthanides and actinides, in the metallic state, can exist as either divalent (such as europium and ytterbium) or trivalent (most other lanthanides) metals. The former have fns2 configurations, whereas the latter have fn−1d1s2 configurations. In 1975, Johansson and Rosengren examined the measured and predicted values for the cohesive energies (enthalpies of crystallization) of the metallic lanthanides and actinides, both as divalent and trivalent metals.[14][15] The conclusion was that the increased binding energy of the [Rn]5f126d17s2 configuration over the [Rn]5f137s2 configuration for mendelevium was not enough to compensate for the energy needed to promote one 5f electron to 6d, as is true also for the very late actinides: thus einsteinium, fermium, mendelevium, and nobelium were expected to be divalent metals.[14] The increasing predominance of the divalent state well before the actinide series concludes is attributed to the relativistic stabilization of the 5f electrons, which increases with increasing atomic number.[16] Thermochromatographic studies with trace quantities of mendelevium by Zvara and Hübener from 1976 to 1982 confirmed this prediction.[13] In 1990, Haire and Gibson estimated mendelevium metal to have an enthalpy of sublimation between 134 and 142 kJ/mol.[13] Divalent mendelevium metal should have a metallic radius of around 194±10 pm.[13] Like the other divalent late actinides (except the once again trivalent lawrencium), metallic mendelevium should assume a face-centered cubic crystal structure.[1] Mendelevium's melting point has been estimated at 800 °C, the same value as that predicted for the neighbouring element nobelium.[17] Its density is predicted to be around 10.3±0.7 g/cm3.[1]

Chemical

[edit]The chemistry of mendelevium is known largely in solution (as available quantities do not allow the creation of pure compounds), in which it can take on the +3 or +2 oxidation states. The +1 state has also been reported, but has not yet been confirmed.[18]

Before mendelevium's discovery, Seaborg and Katz predicted that it should be predominantly trivalent in aqueous solution and hence should behave similarly to other tripositive lanthanides and actinides. After the synthesis of mendelevium in 1955, these predictions were confirmed, first in the observation at its discovery that it eluted just after fermium in the trivalent actinide elution sequence from a cation-exchange column of resin, and later the 1967 observation that mendelevium could form insoluble hydroxides and fluorides that coprecipitated with trivalent lanthanide salts.[18] Cation-exchange and solvent extraction studies led to the conclusion that mendelevium was a trivalent actinide with an ionic radius somewhat smaller than that of the previous actinide, fermium.[18] Mendelevium can form coordination complexes with 1,2-cyclohexanedinitrilotetraacetic acid (DCTA).[18]

In reducing conditions, mendelevium(III) can be easily reduced to mendelevium(II), which is stable in aqueous solution.[18] The standard reduction potential of the E°(Md3+→Md2+) couple was variously estimated in 1967 as −0.10 V or −0.20 V:[18] later 2013 experiments established the value as −0.16±0.05 V.[19] In comparison, E°(Md3+→Md0) should be around −1.74 V, and E°(Md2+→Md0) should be around −2.5 V.[18] Mendelevium(II)'s elution behavior has been compared with that of strontium(II) and europium(II).[18]

In 1973, mendelevium(I) was reported to have been produced by Russian scientists, who obtained it by reducing higher oxidation states of mendelevium with samarium(II). It was found to be stable in neutral water–ethanol solution and be homologous to caesium(I). However, later experiments found no evidence for mendelevium(I) and found that mendelevium behaved like divalent elements when reduced, not like the monovalent alkali metals.[18] Nevertheless, the Russian team conducted further studies on the thermodynamics of cocrystallizing mendelevium with alkali metal chlorides, and concluded that mendelevium(I) had formed and could form mixed crystals with divalent elements, thus cocrystallizing with them. The status of the +1 oxidation state is still tentative.[18]

The electrode potential E°(Md4+→Md3+) was predicted in 1975 to be +5.4 V; 1967 experiments with the strong oxidizing agent sodium bismuthate were unable to oxidize mendelevium(III) to mendelevium(IV).[18]

Atomic

[edit]A mendelevium atom has 101 electrons. They are expected to be arranged in the configuration [Rn]5f137s2 (ground state term symbol 2F7/2), although experimental verification of this electron configuration had not yet been made as of 2006. The fifteen electrons in the 5f and 7s subshells are valence electrons.[20] In forming compounds, three valence electrons may be lost, leaving behind a [Rn]5f12 core: this conforms to the trend set by the other actinides with their [Rn] 5fn electron configurations in the tripositive state. The first ionization potential of mendelevium was measured to be at most (6.58 ± 0.07) eV in 1974, based on the assumption that the 7s electrons would ionise before the 5f ones;[21] this value has not yet been refined further due to the lack to larger samples of mendelevium.[22] The ionic radius of hexacoordinate Md3+ had been preliminarily estimated in 1978 to be around 91.2 pm;[18] 1988 calculations based on the logarithmic trend between distribution coefficients and ionic radius produced a value of 89.6 pm, as well as an enthalpy of hydration of −3654±12 kJ/mol.[18] Md2+ should have an ionic radius of 115 pm and hydration enthalpy −1413 kJ/mol; Md+ should have ionic radius 117 pm.[18]

Isotopes

[edit]Seventeen isotopes of mendelevium are known, with mass numbers from 244 to 260; all are radioactive.[23] The longest-lived isotope is 258Md with a half-life of 51.6 days.[4] Nevertheless, the shorter-lived 256Md (half-life 77.7 minutes) is more often used in chemical experiments because it can be produced in larger quantities from einsteinium,[23] as 258Md would require 255Es, of which significant quantities are available only as a minor component of an isotopic mixture.

The half-lives of mendelevium isotopes mostly increase smoothly (apart from odd/even effects) toward higher mass, up to 258Md, then decrease (as indicated by what experimental data is available) as spontaneous fission becomes the dominant decay mode;[23] the second longest-living isotope is 260Md, the heaviest known, with a half-life of 27.8 days.[4] Mendelevium is the last element that has any known isotope with a half-life longer than a day.[4]

Mendelevium-256, the currently most important isotope of mendelevium, decays about 90% through electron capture and 10% through alpha decay.[23] It is most easily detected through the spontaneous fission of its electron capture daughter fermium-256, but in the presence of other nuclides that undergo spontaneous fission, alpha decays at the characteristic energies for mendelevium-256 (7.205 and 7.139 MeV) can provide more useful identification.[24]

Production and isolation

[edit]The lightest isotopes (244Md to 247Md) are mostly produced through bombardment of bismuth targets with argon ions, while slightly heavier ones (248Md to 253Md) are produced by bombarding plutonium and americium targets with ions of carbon and nitrogen. The most important and most stable isotopes are in the range from 254Md to 258Md and are produced through bombardment of einsteinium with alpha particles: einsteinium-253, −254, and −255 can all be used. 259Md is produced as a daughter of 259No, and 260Md can be produced in a transfer reaction between einsteinium-254 and oxygen-18.[23] Typically, the most commonly used isotope 256Md is produced by bombarding either einsteinium-253 or −254 with alpha particles: einsteinium-254 is preferred when available because it has a longer half-life and therefore can be used as a target for longer.[23] Using available microgram quantities of einsteinium, femtogram quantities of mendelevium-256 may be produced.[23]

The recoil momentum of the produced mendelevium-256 atoms is used to bring them physically far away from the einsteinium target from which they are produced, bringing them onto a thin foil of metal (usually beryllium, aluminium, platinum, or gold) just behind the target in a vacuum.[24] This eliminates the need for immediate chemical separation, which is both costly and prevents reusing of the expensive einsteinium target.[24] The mendelevium atoms are then trapped in a gas atmosphere (frequently helium), and a gas jet from a small opening in the reaction chamber carries the mendelevium along.[24] Using a long capillary tube, and including potassium chloride aerosols in the helium gas, the mendelevium atoms can be transported over tens of meters to be chemically analysed and have their quantity determined.[8][24] The mendelevium can then be separated from the foil material and other fission products by applying acid to the foil and then coprecipitating the mendelevium with lanthanum fluoride, then using a cation-exchange resin column with a 10% ethanol solution saturated with hydrochloric acid, acting as an eluant. However, if the foil is made of gold and thin enough, it is enough to simply dissolve the gold in aqua regia before separating the trivalent actinides from the gold using anion-exchange chromatography, the eluant being 6 M hydrochloric acid.[24]

Mendelevium can finally be separated from the other trivalent actinides using selective elution from a cation-exchange resin column, the eluant being ammonia α-HIB.< Using the gas-jet method often renders the first two steps unnecessary.[24]

Another possible way to separate the trivalent actinides is via solvent extraction chromatography using bis-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid (abbreviated as HDEHP) as the stationary organic phase and nitric acid as the mobile aqueous phase. The actinide elution sequence is reversed from that of the cation-exchange resin column, so that the heavier actinides elute later. The mendelevium separated by this method has the advantage of being free of organic complexing agent compared to the resin column; the disadvantage is that mendelevium then elutes very late in the elution sequence, after fermium.[8][24]

Another method to isolate mendelevium exploits the distinct elution properties of Md2+ from those of Es3+ and Fm3+. The initial steps are the same as above, and employs HDEHP for extraction chromatography, but coprecipitates the mendelevium with terbium fluoride instead of lanthanum fluoride. Then, 50 mg of chromium is added to the mendelevium to reduce it to the +2 state in 0.1 M hydrochloric acid with zinc or mercury.[24] The solvent extraction then proceeds, and while the trivalent and tetravalent lanthanides and actinides remain on the column, mendelevium(II) does not and stays in the hydrochloric acid. It is then reoxidized to the +3 state using hydrogen peroxide and then isolated by selective elution with 2 M hydrochloric acid (to remove impurities, including chromium) and finally 6 M hydrochloric acid (to remove the mendelevium).[24] It is also possible to use a column of cationite and zinc amalgam, using 1 M hydrochloric acid as an eluant, to effect the reduction.[24] Thermochromatographic chemical isolation could be achieved using the volatile mendelevium hexafluoroacetylacetonate: the analogous fermium compound is known and similar.[24]

Toxicity

[edit]Though few people come in contact with mendelevium, the International Commission on Radiological Protection has set annual exposure limits for the most stable isotope. For mendelevium-258, the ingestion limit was set at 9×105 becquerels (1 Bq = 1 decay per second). Given the half-life of this isotope, this is only 2.48 ng (nanograms). The inhalation limit is at 6000 Bq or 16.5 pg (picogram).[25]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The density is calculated from the predicted metallic radius (Silva 2006, p. 1635) and the predicted close-packed crystal structure (Fournier 1976).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Fournier, Jean-Marc (1976). "Bonding and the electronic structure of the actinide metals". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 37 (2): 235–244. Bibcode:1976JPCS...37..235F. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(76)90167-0.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 28. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Sato, Tetsuya K.; Asai, Masato; Borschevsky, Anastasia; Beerwerth, Randolf; Kaneya, Yusuke; Makii, Hiroyuki; Mitsukai, Akina; Nagame, Yuichiro; Osa, Akihiko; Toyoshima, Atsushi; Tsukada, Kazuki; Sakama, Minoru; Takeda, Shinsaku; Ooe, Kazuhiro; Sato, Daisuke; Shigekawa, Yudai; Ichikawa, Shin-ichi; Düllmann, Christoph E.; Grund, Jessica; Renisch, Dennis; Kratz, Jens V.; Schädel, Matthias; Eliav, Ephraim; Kaldor, Uzi; Fritzsche, Stephan; Stora, Thierry (25 October 2018). "First Ionization Potentials of Fm, Md, No, and Lr: Verification of Filling-Up of 5f Electrons and Confirmation of the Actinide Series". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 140 (44): 14609–14613. doi:10.1021/jacs.8b09068.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3) 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ a b c d Ghiorso, A.; Harvey, B.; Choppin, G.; Thompson, S.; Seaborg, Glenn T. (1955). New Element Mendelevium, Atomic Number 101. Vol. 98. pp. 1518–1519. Bibcode:1955PhRv...98.1518G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.98.1518. ISBN 9789810214401.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help);|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Choppin, Gregory R. (2003). "Mendelevium". Chemical and Engineering News. 81 (36).

- ^ Hofmann, Sigurd (2002). On beyond uranium: journey to the end of the periodic table. CRC Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-0-415-28496-7.

- ^ a b c Hall, Nina (2000). The new chemistry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-521-45224-3.

- ^ 101. Mendelevium – Elementymology & Elements Multidict. Peter van der Krogt.

- ^ Chemistry, International Union of Pure and Applied (1955). Comptes rendus de la confèrence IUPAC.

- ^ Chemistry, International Union of Pure and Applied (1957). Comptes rendus de la confèrence IUPAC.

- ^ Haire, Richard G. (2006). "Einsteinium". In Morss, Lester R.; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (PDF). Vol. 3 (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. pp. 1577–1620. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3598-5_12. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-17. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- ^ a b c d e Silva, pp. 1634–5

- ^ a b Silva, pp. 1626–8

- ^ Johansson, Börje; Rosengren, Anders (1975). "Generalized phase diagram for the rare-earth elements: Calculations and correlations of bulk properties". Physical Review B. 11 (8): 2836–2857. Bibcode:1975PhRvB..11.2836J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.11.2836.

- ^ Hulet, E. K. (1980). "Chapter 12. Chemistry of the Heaviest Actinides: Fermium, Mendelevium, Nobelium, and Lawrencium". In Edelstein, Norman M. (ed.). Lanthanide and Actinide Chemistry and Spectroscopy. ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 131. pp. 239–263. doi:10.1021/bk-1980-0131.ch012. ISBN 9780841205680.

- ^ Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 4.121 – 4.123. ISBN 978-1439855119.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Silva, pp. 1635–6

- ^ Toyoshima, Atsushi; Li, Zijie; Asai, Masato; Sato, Nozomi; Sato, Tetsuya K.; Kikuchi, Takahiro; Kaneya, Yusuke; Kitatsuji, Yoshihiro; Tsukada, Kazuaki; Nagame, Yuichiro; Schädel, Matthias; Ooe, Kazuhiro; Kasamatsu, Yoshitaka; Shinohara, Atsushi; Haba, Hiromitsu; Even, Julia (11 October 2013). "Measurement of the Md3+/Md2+ Reduction Potential Studied with Flow Electrolytic Chromatography". Inorganic Chemistry. 52 (21): 12311–3. doi:10.1021/ic401571h. PMID 24116851.

- ^ Silva, pp. 1633–4

- ^ Martin, W. C.; Hagan, Lucy; Reader, Joseph; Sugan, Jack (1974). "Ground Levels and Ionization Potentials for Lanthanide and Actinide Atoms and Ions" (PDF). J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 3 (3): 771–9. Bibcode:1974JPCRD...3..771M. doi:10.1063/1.3253147. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-11. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

- ^ David R. Lide (ed), CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 84th Edition. CRC Press. Boca Raton, Florida, 2003; Section 10, Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics; Ionization Potentials of Atoms and Atomic Ions

- ^ a b c d e f g Silva, pp. 1630–1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Silva, pp. 1631–3

- ^ Koch, Lothar (2000). "Transuranium Elements". Transuranium Elements, in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_167. ISBN 978-3527306732.

Bibliography

[edit]- Silva, Robert J. (2006). "Fermium, Mendelevium, Nobelium, and Lawrencium" (PDF). In Morss, Lester R.; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements. Vol. 3 (3rd ed.). Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 1621–1651. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3598-5_13. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-17.

Further reading

[edit]- Hoffman, D.C., Ghiorso, A., Seaborg, G. T. The transuranium people: the inside story, (2000), 201–229

- Morss, L. R., Edelstein, N. M., Fuger, J., The chemistry of the actinide and transactinide element, 3, (2006), 1630–1636

- A Guide to the Elements – Revised Edition, Albert Stwertka, (Oxford University Press; 1998) ISBN 0-19-508083-1

External links

[edit]- Los Alamos National Laboratory – Mendelevium

- It's Elemental – Mendelevium

- Mendelevium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- Environmental Chemistry – Md info

Mendelevium

View on GrokipediaHistory

Discovery

In the years following World War II, scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (then known as the Radiation Laboratory) made significant strides in synthesizing transuranic elements beyond uranium, leveraging particle accelerators and nuclear reactors to probe the limits of the periodic table. This effort built directly on the 1952 discoveries of einsteinium (element 99) and fermium (element 100), which were identified in debris from the Ivy Mike thermonuclear test and processed at Berkeley, providing the first microgram quantities of heavy target materials necessary for further transmutations.[3][2] The breakthrough for element 101 came through a targeted experiment led by Albert Ghiorso and Glenn T. Seaborg, with key contributions from Bernard G. Harvey, Gregory R. Choppin, and Stanley G. Thompson. Using the laboratory's 60-inch cyclotron, the team bombarded a thin layer of einsteinium-253 (containing about 10^9 atoms deposited on a gold foil) with alpha particles (helium-4 ions accelerated to 42 MeV). This (α, n) reaction aimed to produce mendelevium-256, with the recoiling product atoms collected on a catcher foil positioned behind the target to facilitate rapid chemical separation. Over multiple short irradiation runs conducted in early 1955, the experiment yielded only 17 atoms of the new element in total across eight separate trials.[1][2] Confirmation of element 101's synthesis relied on ion-exchange chromatography for chemical identification, where the collected atoms were eluted in the expected position for eka-thulium (the predicted analog in the actinide series) using a cation resin column. The definitive proof came from observing the spontaneous fission decay of the daughter product fermium-256, which has a half-life of approximately 2.6 hours, distinguishing it from other possible contaminants. No direct observation of mendelevium's own alpha decay was possible due to the minuscule quantity, but the genetic linkage via electron capture from Md-256 to Fm-256 verified the atomic number 101.[2][5] The synthesis occurred on February 19, 1955, marking the first time a new element was identified strictly through chemical means on an atom-by-atom basis, without reliance on isotopic mass separation. The discovery was publicly announced later that year and formally reported in a seminal paper, advancing the understanding of actinide chemistry and the actinide concept proposed by Seaborg.[3]Naming

Mendelevium was named in honor of the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, who developed the periodic table of elements in 1869 and made key predictions about the properties of undiscovered elements, including those in the actinide series.[6] The discovery team at the University of California, Berkeley, led by Albert Ghiorso, Bernard G. Harvey, Gregory R. Choppin, Stanley G. Thompson, and Glenn T. Seaborg, proposed the name "mendelevium" with symbol "Md" in their 1955 publication announcing the element's synthesis, recognizing Mendeleev's theoretical contributions to understanding heavy element behavior.[5] The proposal occurred amid Cold War tensions, where heavy element research was sensitive due to its links to nuclear weapons programs; nonetheless, Seaborg secured U.S. government approval for naming the element after a Russian scientist, a bold gesture at the time. Initially kept somewhat confidential, the name was formally proposed to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in 1955. There were no competing name proposals, and the secrecy surrounding early details was later declassified without significant controversy.[7][8] IUPAC officially accepted the name "mendelevium" and symbol "Md" in 1955, confirming the usage from the discovery publication. This naming marked a notable recognition of chemical theory over experimental physics, as mendelevium was among the first transuranic elements explicitly honoring a chemist for foundational periodic law work, shifting emphasis in the actinide series.[6]Production

Synthesis

Mendelevium atoms are produced exclusively in laboratory settings through heavy-ion bombardment techniques employing particle accelerators, as the element does not occur naturally. The primary synthesis method relies on the fusion-evaporation reaction where an einsteinium target is bombarded with alpha particles (helium-4 nuclei), exemplified by the reaction .[9] This approach was pioneered in 1955, marking the first identification of mendelevium on an atom-by-atom basis. Einsteinium targets, typically prepared as thin foils containing microgram quantities of isotopes like , are used to minimize energy loss of the incident beam while maximizing interaction probability. Alpha particle beams with energies in the range of 40-80 MeV are directed at these targets to provide sufficient kinetic energy to surmount the Coulomb barrier and initiate the nuclear reaction.[10] Production occurs at specialized facilities, including the 88-Inch Cyclotron at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which delivers intense heavy-ion beams for transactinide synthesis, and heavy-ion accelerators at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Germany.[11] These cyclotrons evolved from the 60-inch model used in the initial 1955 experiment to modern superconducting variants, enabling higher beam intensities and improved isotope yields.[12] Due to the minuscule reaction cross-sections and the scarcity of target material, yields remain extremely low, often limited to a few atoms per experiment or several per day under optimal conditions. For instance, early productions yielded around 17 atoms over multiple irradiation runs, while contemporary efforts at the 88-Inch Cyclotron have generated as few as 10 atoms of specific isotopes over weeks of operation.[11] Alternative synthesis routes for heavier mendelevium isotopes include multi-nucleon transfer reactions, such as those involving targets bombarded with oxygen-16 or neon-22 ions at energies around 100 MeV, where nucleons are exchanged between projectile and target to form neutron-richer products. Neutron capture on fermium targets in high-flux neutron environments, followed by beta decay chains, can also contribute to the production of heavier isotopes, though this method is less commonly employed for mendelevium due to competing fission processes.[13]Isolation

The isolation of mendelevium from the products of nuclear reactions primarily relies on ion-exchange chromatography, employing cation-exchange resins such as Dowex-50 and an eluent of ammonium α-hydroxyisobutyrate to separate the trivalent Md^{3+} ions from co-produced lanthanides and lighter actinides. This method exploits differences in distribution coefficients, where the adsorption strength decreases across the actinide series, allowing selective elution based on ionic radius and complexation tendencies.[10] In typical separations, mendelevium elutes immediately following fermium when using 0.3–0.5 M α-hydroxyisobutyrate at elevated temperatures (around 80–90°C) to enhance resolution, with a separation factor relative to curium of approximately 0.05.[14][15] The process begins with the raw mixture from alpha-particle bombardment of einsteinium targets, which is dissolved and loaded onto the resin column for rapid elution to accommodate the short half-life of key isotopes like ^{256}Md (t_{1/2} = 77 min).[10] Detection during elution occurs on-line through α-particle counting of the characteristic 7.1–7.2 MeV emissions from ^{256}Md decay or by monitoring spontaneous fission events from its daughter ^{256}Fm, with fractions collected on metal foils or disks for further analysis.[10] Due to mendelevium's high reactivity, all handling is conducted in inert atmospheres or vacuum to minimize oxidation or hydrolysis. The ultra-low yields—often limited to single atoms or tens per experiment—pose significant challenges, requiring highly efficient, rapid techniques to isolate and study the element before decay; early manual column operations have largely been replaced by automated flow-based systems for improved speed and reproducibility.[10] Purity is verified by the clean elution profile and confirmatory tests such as solvent extraction or coprecipitation, with occasional use of gas-phase chromatography to separate any volatile contaminants or recoil-implanted species.[10][16]Properties

Physical properties

Mendelevium is anticipated to exhibit a silvery-white metallic luster, akin to other elements in the actinide series, though this remains unconfirmed due to the absence of bulk samples; only trace quantities, typically a few atoms, have been produced.[17] The estimated density of mendelevium at room temperature is 10.3 g/cm³, derived from extrapolations accounting for the lanthanide contraction and trends in atomic volumes across the actinides; this prediction aligns with the influence of its atomic radius on packing efficiency.[18] Mendelevium is predicted to be a solid at standard temperature and pressure, with a melting point of approximately 827 °C based on bonding models and comparisons to neighboring actinides.[2] In the solid state, mendelevium is expected to display paramagnetic behavior, consistent with its odd number of electrons in the 5f subshell. Gas-phase studies, including thermochromatographic experiments on trace amounts, provide data on its low volatility, supporting predictions of limited vapor pressure at elevated temperatures.[10] The standard enthalpy of sublimation for mendelevium is estimated at 134–142 kJ/mol, drawn from thermodynamic modeling of superheavy actinides.[19]Chemical properties

Mendelevium primarily exhibits a +3 oxidation state, forming the Md ion, which is characteristic of late actinides and aligns with its position in the periodic table. This trivalent state dominates its aqueous chemistry, with an ionic radius estimated at approximately 0.89 Å for coordination number 6, slightly smaller than that of fermium due to lanthanide contraction trends extended into the actinides. A stable +2 oxidation state (Md) is also accessible in solution, marking mendelevium as the first actinide to demonstrate divalency under these conditions, with a reduction potential for the Md/Md couple of about -0.16 V versus the standard hydrogen electrode. No +4 oxidation state has been observed, despite attempts using strong oxidants like sodium bismuthate.[10][20][21] In terms of reactivity, mendelevium behaves as a typical trivalent actinide, readily forming compounds such as the halides MdCl and MdF, as well as the sesquioxide MdO. These are inferred from elution behaviors and chromatographic studies rather than bulk isolation, given the element's production in trace amounts. Mendelevium can be extracted from hydrochloric acid solutions into tri-n-butyl phosphate, indicating the formation of chloride complexes that facilitate separation from other actinides like fermium, with distribution ratios supporting higher separation factors in HCl compared to nitric acid systems. Its reactivity in aqueous media mirrors that of lanthanides like ytterbium and europium, particularly in the +2 state, where it shows increased volatility and amalgam formation with mercury.[10][22][2] Mendelevium forms coordination complexes with ligands such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), consistent with its trivalent ionic character, and these complexes exhibit stability similar to those of preceding actinides. Elution studies using cation-exchange resins with α-hydroxyisobutyric acid or citrate buffers place mendelevium after nobelium in chromatographic sequences, confirming its expected periodic trend position. Relativistic effects play a minor role in its overall chemistry, primarily through 5f electron contraction that slightly reduces the Md ion size and influences redox potentials, though these impacts are less pronounced than in heavier transactinides.[10][23] Experimental investigations of mendelevium's chemical properties rely on single-atom techniques due to its short-lived isotopes, such as Md (half-life 77.7 minutes). On-line isothermal gas-phase chromatography has been used to study fluoride and chloride complexes, revealing adsorption enthalpies that align with trivalent actinide trends and aid in distinguishing oxidation states. Flow electrolytic chromatography further enables redox studies, confirming the accessibility of the +2 state via reduction in acidic media. These methods underscore mendelevium's position as a bridge between typical actinide behavior and emerging relativistic influences in superheavy elements.[10][21]Atomic properties

Mendelevium has atomic number 101 and no stable isotopes, resulting in a conventional standard atomic weight of .[24] The ground-state electron configuration of the neutral mendelevium atom is [Rn] , corresponding to the term symbol .[9][25] This configuration places mendelevium as the third-to-last element in the actinide series, with its $5f$ subshell nearly filled, influencing its atomic and ionic behavior in line with f-block trends. The first ionization energy of mendelevium is estimated at 635 kJ/mol (equivalent to 6.58 eV), determined through semiempirical methods and interpolation from experimental values of neighboring actinides.[9][25] This value reflects the increasing ionization energies across the actinide series due to enhanced effective nuclear charge and lanthanide/actinide contraction, which progressively stabilizes the $5f$ electrons. The ionic radius of the Md ion, the predominant oxidation state, is extrapolated to approximately 0.89 Å for coordination number 6, based on linear trends in the actinide contraction observed for earlier elements like holmium and fermium. This size positions Md comparably to lighter lanthanide ions, underscoring the similarity in ionic dimensions between late actinides and lanthanides. Mendelevium in the +3 oxidation state is expected to exhibit paramagnetic behavior arising from four unpaired $5f^{3+} configuration, consistent with Hund's rule maximization of spin in the partially filled $5f subshell.[26] This paramagnetism aligns with magnetic susceptibility trends in tripositive actinide ions, where unpaired electrons dominate the response.Isotopes

Mendelevium has 17 known isotopes, with mass numbers ranging from 244 to 260, all of which are radioactive and have no stable forms. These isotopes are produced in heavy-ion fusion-evaporation reactions and exhibit half-lives spanning from milliseconds to over a month, primarily decaying via alpha emission, electron capture (EC), or spontaneous fission (SF). The most stable isotope is ^{258}Md, with a half-life of 51.5 ± 0.3 days, decaying almost exclusively by alpha emission to ^{254}Fm. The lightest known isotope, ^{244}Md, was discovered in 2020 at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory using the 88-Inch Cyclotron, produced via the reaction ^{209}Bi(^{40}Ar,5n) at a beam energy of 233 MeV. This isotope has a half-life of 380 ± 60 ms and decays predominantly by alpha emission (86 ± 5%) to excited states in ^{240}Bk, with a minor branch (14 ± 5%) via electron capture to ^{244}Es; an isomeric state ^{244m}Md with a half-life of 5 ± 2 ms has also been observed. This discovery filled a significant gap in the chart of nuclides for neutron-deficient actinides and provided the first direct observation of the alpha decay of ^{236}Bk. No isotopes lighter than ^{244}Md have been observed to date. Heavier isotopes up to ^{260}Md have been synthesized, primarily through bombardments involving californium or einsteinium targets, but no mendelevium isotopes beyond mass 260 are known.[27] The decay properties of mendelevium isotopes reflect trends typical of transfermium elements, with half-lives generally increasing with mass number up to ^{258}Md before decreasing due to increasing fission probabilities. Neutron-rich isotopes are often produced via multi-neutron evaporation channels, while lighter ones arise from reactions with higher neutron evaporation. For example, ^{256}Md, commonly used in early chemical studies of the element, has a half-life of 77.7 ± 1.8 minutes and decays 90.8% by EC to ^{256}Fm, 9.2% by alpha emission to ^{252}Es, and less than 3% by SF. Isotopes with odd mass numbers, such as ^{257}Md (half-life 5.52 ± 0.05 hours, primarily EC and alpha decay), exhibit enhanced stability relative to their even-mass neighbors, attributed to nuclear shell effects stabilizing the odd-neutron configuration, particularly the 5f^{13} subshell. The following table summarizes the ground-state properties of known mendelevium isotopes, based on evaluated nuclear data (isomeric states omitted for brevity; branching ratios approximate where dominant modes are indicated).| Mass Number | Half-Life | Primary Decay Mode(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 244 | 380(60) ms | α (86%), EC (14%) |

| 245 | 0.90(25) ms | α, SF |

| 246 | 0.9(2) s | α, SF, EC |

| 247 | 1.2(1) s | α (>99.9%), SF (<0.1%) |

| 248 | 7(3) s | EC (80%), α (20%) |

| 249 | 21.7(20) s | α (>60%), EC (<40%) |

| 250 | 52(6) s | EC (93%), α (7%) |

| 251 | 4.0(5) min | EC (≥90%), α (≤10%) |

| 252 | 2.3(8) min | EC (100%) |

| 253 | 6(1) min | EC (99.3%), α (0.7%) |

| 254 | 10(3) min | EC (100%) |

| 255 | 27(2) min | EC (93%), α (7%) |

| 256 | 77.7(18) min | EC (90.8%), α (9.2%), SF (<3%) |

| 257 | 5.52(5) h | EC (85%), α (15%), SF (<1%) |

| 258 | 51.50(29) d | α (100%), SF (≤0.003%) |

| 259 | 1.60(6) h | SF (100%), α (<1.3%) |

| 260 | 31.8(5) d | SF (≤25%), α (≤23%), EC (≤10%), β⁻ |