Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Emulator

View on Wikipedia

[1]In computing, an emulator is hardware or software that enables one computer system (called the host) to behave like another computer system (called the guest). An emulator typically enables the host system to run software or use peripheral devices designed for the guest system. Emulation refers to the ability of a computer program in an electronic device to emulate (or imitate) another program or device.

Many printers, for example, are designed to emulate HP LaserJet printers because a significant amount of software is written specifically for HP models. If a non-HP printer emulates an HP printer, any software designed for an actual HP printer will also function on the non-HP device, producing equivalent print results. Since at least the 1990s, many video game enthusiasts and hobbyists have used emulators to play classic arcade games from the 1980s using the games' original 1980s machine code and data, which is interpreted by a current-era system, and to emulate old video game consoles (see video game console emulator).

A hardware emulator is an emulator which takes the form of a hardware device. Examples include the DOS-compatible card installed in some 1990s-era Macintosh computers, such as the Centris 610 or Performa 630, that allowed them to run personal computer (PC) software programs and field-programmable gate array-based hardware emulators. The Church–Turing thesis implies that theoretically, any operating environment can be emulated within any other environment, assuming memory limitations are ignored. However, in practice, it can be quite difficult, particularly when the exact behavior of the system to be emulated is not documented and has to be deduced through reverse engineering. It also says nothing about timing constraints; if the emulator does not perform as quickly as it did using the original hardware, the software inside the emulation may run much more slowly (possibly triggering timer interrupts that alter behavior).

"Can a Commodore 64 emulate MS-DOS?" Yes, it's possible for a [Commodore] 64 to emulate an IBM PC [which uses MS-DOS], in the same sense that it's possible to bail out Lake Michigan with a teaspoon.

— Letter to Compute! and editorial answer, April 1988 [2]

Types

[edit]

Most emulators just emulate a hardware architecture—if operating system firmware or software is required for the desired software, it must be provided as well (and may itself be emulated). Both the OS and the software will then be interpreted by the emulator, rather than being run by native hardware. Apart from this interpreter for the emulated binary machine's language, some other hardware (such as input or output devices) must be provided in virtual form as well; for example, if writing to a specific memory location should influence what is displayed on the screen, then this would need to be emulated. While emulation could, if taken to the extreme, go down to the atomic level, basing its output on a simulation of the actual circuitry from a virtual power source, this would be a highly unusual solution. Emulators typically stop at a simulation of the documented hardware specifications and digital logic. Sufficient emulation of some hardware platforms requires extreme accuracy, down to the level of individual clock cycles, undocumented features, unpredictable analog elements, and implementation bugs. This is particularly the case with classic home computers such as the Commodore 64, whose software often depends on highly sophisticated low-level programming tricks invented by game programmers and the "demoscene".

In contrast, some other platforms have had very little use of direct hardware addressing, such as an emulator for the PlayStation 4.[citation needed] In these cases, a simple compatibility layer may suffice. This translates system calls for the foreign system into system calls for the host system e.g., the Linux compatibility layer used on *BSD to run closed source Linux native software on FreeBSD and NetBSD.[3] For example, while the Nintendo 64 graphic processor was fully programmable, most games used one of a few pre-made programs, which were mostly self-contained and communicated with the game via FIFO; therefore, many emulators do not emulate the graphic processor at all, but simply interpret the commands received from the CPU as the original program would. Developers of software for embedded systems or video game consoles often design their software on especially accurate emulators called simulators before trying it on the real hardware. This is so that software can be produced and tested before the final hardware exists in large quantities, so that it can be tested without taking the time to copy the program to be debugged at a low level and without introducing the side effects of a debugger. In many cases, the simulator is actually produced by the company providing the hardware, which theoretically increases its accuracy. Math co-processor emulators allow programs compiled with math instructions to run on machines that do not have the co-processor installed, but the extra work done by the CPU may slow the system down. If a math coprocessor is not installed or present on the CPU, when the CPU executes any co-processor instruction it will make a determined interrupt (coprocessor not available), calling the math emulator routines. When the instruction is successfully emulated, the program continues executing.

Logic simulators

[edit]Logic simulation is the use of a computer program to simulate the operation of a digital circuit such as a processor.[1] This is done after a digital circuit has been designed in logic equations, but before the circuit is fabricated in hardware.

Functional emulators

[edit]Functional simulation is the use of a computer program to simulate the execution of a second computer program written in symbolic assembly language or compiler language, rather than in binary machine code. By using a functional simulator, programmers can execute and trace selected sections of source code to search for programming errors (bugs), without generating binary code. This is distinct from simulating execution of binary code, which is software emulation. The first functional simulator was written by Autonetics about 1960[citation needed] for testing assembly language programs for later execution in military computer D-17B. This made it possible for flight programs to be written, executed, and tested before D-17B computer hardware had been built. Autonetics also programmed a functional simulator for testing flight programs for later execution in the military computer D-37C.

Video game console emulators

[edit]Video game console emulators are programs that allow a personal computer or video game console to emulate another video game console. They are most often used to play older 1980s to 2000s-era video games on modern personal computers and more contemporary video game consoles. They are also used to translate games into other languages, to modify existing games, and in the development process of "home brew" DIY demos and in the creation of new games for older systems. The Internet has helped in the spread of console emulators, as most - if not all - would be unavailable for sale in retail outlets. Examples of console emulators that have been released in the last few decades are: RPCS3, Dolphin, Cemu, PCSX2, PPSSPP, ZSNES, Citra, ePSXe, Project64, Visual Boy Advance, Nestopia, and Yuzu.

Due to their popularity, emulators have been impersonated by malware. Most of these emulators are for video game consoles like the Xbox 360, Xbox One, Nintendo 3DS, etc. Generally such emulators make currently impossible claims such as being able to run Xbox One and Xbox 360 games in a single program.[4]

Legal issues

[edit]As computers and global computer networks continued to advance and emulator developers grew more skilled in their work, the length of time between the commercial release of a console and its successful emulation began to shrink. Fifth generation consoles such as Nintendo 64, PlayStation and sixth generation handhelds, such as the Game Boy Advance, saw significant progress toward emulation during their production. This led to an effort by console manufacturers to stop unofficial emulation, but consistent failures such as Sega v. Accolade 977 F.2d 1510 (9th Cir. 1992), Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc. v. Connectix Corporation 203 F.3d 596 (2000), and Sony Computer Entertainment America v. Bleem 214 F.3d 1022 (2000),[5] have had the opposite effect. According to all legal precedents, emulation is legal within the United States. However, unauthorized distribution of copyrighted code remains illegal, according to both country-specific copyright and international copyright law under the Berne Convention.[6][better source needed] Under United States law, obtaining a dumped copy of the original machine's BIOS is legal under the ruling Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc. v. Nintendo of America, Inc., 964 F.2d 965 (9th Cir. 1992) as fair use as long as the user obtained a legally purchased copy of the machine. To mitigate this however, several emulators for platforms such as Game Boy Advance are capable of running without a BIOS file, using high-level emulation to simulate BIOS subroutines at a slight cost in emulation accuracy.[7][8][9]

Terminal

[edit]Terminal emulators are software programs that provide modern computers and devices interactive access to applications running on mainframe computer operating systems or other host systems such as HP-UX or OpenVMS. Terminals such as the IBM 3270 or VT100 and many others are no longer produced as physical devices. Instead, software running on modern operating systems simulates a "dumb" terminal and is able to render the graphical and text elements of the host application, send keystrokes and process commands using the appropriate terminal protocol. Some terminal emulation applications include Attachmate Reflection, IBM Personal Communications, and Micro Focus Rumba.

Other types

[edit]Other types of emulators include:

- Hardware emulator: the process of imitating the behavior of one or more pieces of hardware (typically a system under design) with another piece of hardware, typically a special purpose emulation system

- In-circuit emulator: the use of a hardware device to debug the software of an embedded system

- Floating-point emulator: Some floating-point hardware only supports the simplest operations: addition, subtraction, and multiplication. In systems without any floating-point hardware, the CPU emulates it using a series of simpler fixed-point arithmetic operations that run on the integer arithmetic logic unit.

- Instruction set simulator in a high-level programming language: Mimics the behavior of a mainframe or microprocessor by "reading" instructions and maintaining internal variables which represent the processor's registers.

- Network emulation: a technique for testing the performance of real applications over a virtual network. This is different from network simulation where virtual models of traffic, network models, channels, and protocols are applied.

- Server emulator: Multiplayer video games often rely on an online game server, which may or may not be available for on-premises installation. A server emulator is an unofficial on-premises server that imitates the behavior of the official online server, even though its internal working might be different.

- Semulation: the process of controlling an emulation through a simulator

Structure and organization

[edit]This article's section named "Structure and organization" needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

Typically, an emulator is divided into modules that correspond roughly to the emulated computer's subsystems. Most often, an emulator will be composed of the following modules:

- a CPU emulator or CPU simulator (the two terms are mostly interchangeable in this case), unless the target being emulated has the same CPU architecture as the host, in which case a virtual machine layer may be used instead

- a memory subsystem module

- various input/output (I/O) device emulators

Buses are often not emulated, either for reasons of performance or simplicity, and virtual peripherals communicate directly with the CPU or the memory subsystem.

Memory subsystem

[edit]It is possible for the memory subsystem emulation to be reduced to simply an array of elements each sized like an emulated word; however, this model fails very quickly as soon as any location in the computer's logical memory does not match physical memory. This clearly is the case whenever the emulated hardware allows for advanced memory management (in which case, the MMU logic can be embedded in the memory emulator, made a module of its own, or sometimes integrated into the CPU simulator). Even if the emulated computer does not feature an MMU, though, there are usually other factors that break the equivalence between logical and physical memory: many (if not most) architectures offer memory-mapped I/O; even those that do not often have a block of logical memory mapped to ROM, which means that the memory-array module must be discarded if the read-only nature of ROM is to be emulated. Features such as bank switching or segmentation may also complicate memory emulation. As a result, most emulators implement at least two procedures for writing to and reading from logical memory, and it is these procedures' duty to map every access to the correct location of the correct object.

On a base-limit addressing system where memory from address 0 to address ROMSIZE-1 is read-only memory, while the rest is RAM, something along the line of the following procedures would be typical:

void WriteMemory(word Address, word Value) {

word RealAddress;

RealAddress = Address + BaseRegister;

if ((RealAddress < LimitRegister) &&

(RealAddress > ROMSIZE)) {

Memory[RealAddress] = Value;

} else {

RaiseInterrupt(INT_SEGFAULT);

}

}

word ReadMemory(word Address) {

word RealAddress;

RealAddress=Address+BaseRegister;

if (RealAddress < LimitRegister) {

return Memory[RealAddress];

} else {

RaiseInterrupt(INT_SEGFAULT);

return NULL;

}

}

CPU simulator

[edit]The CPU simulator is often the most complicated part of an emulator. Many emulators are written using "pre-packaged" CPU simulators, in order to concentrate on good and efficient emulation of a specific machine. The simplest form of a CPU simulator is an interpreter, which is a computer program that follows the execution flow of the emulated program code and, for every machine code instruction encountered, executes operations on the host processor that are semantically equivalent to the original instructions. This is made possible by assigning a variable to each register and flag of the simulated CPU. The logic of the simulated CPU can then more or less be directly translated into software algorithms, creating a software re-implementation that basically mirrors the original hardware implementation.

The following example illustrates how CPU simulation can be accomplished by an interpreter. In this case, interrupts are checked-for before every instruction executed, though this behavior is rare in real emulators for performance reasons (it is generally faster to use a subroutine to do the work of an interrupt).

void Execute(void) {

if (Interrupt != INT_NONE) {

SuperUser = TRUE;

WriteMemory(++StackPointer, ProgramCounter);

ProgramCounter = InterruptPointer;

}

switch (ReadMemory(ProgramCounter++)) {

/*

* Handling of every valid instruction

* goes here...

*/

default:

Interrupt = INT_ILLEGAL;

}

}

Interpreters are very popular as computer simulators, as they are much simpler to implement than more time-efficient alternative solutions, and their speed is more than adequate for emulating computers of more than roughly a decade ago on modern machines. However, the speed penalty inherent in interpretation can be a problem when emulating computers whose processor speed is on the same order of magnitude as the host machine[dubious – discuss]. Until not many years ago, emulation in such situations was considered completely impractical by many[dubious – discuss].

What allowed breaking through this restriction were the advances in dynamic recompilation techniques[dubious – discuss]. Simple a priori translation of emulated program code into code runnable on the host architecture is usually impossible because of several reasons:

- code may be modified while in RAM, even if it is modified only by the emulated operating system when loading the code (for example from disk)

- there may not be a way to reliably distinguish data (which should not be translated) from executable code.

Various forms of dynamic recompilation, including the popular Just In Time compiler (JIT) technique, try to circumvent these problems by waiting until the processor control flow jumps into a location containing untranslated code, and only then ("just in time") translates a block of the code into host code that can be executed. The translated code is kept in a code cache[dubious – discuss], and the original code is not lost or affected; this way, even data segments can be (meaninglessly) translated by the recompiler, resulting in no more than a waste of translation time. Speed may not be desirable as some older games were not designed with the speed of faster computers in mind. A game designed for a 30 MHz PC with a level timer of 300 game seconds might only give the player 30 seconds on a 300 MHz PC. Other programs, such as some DOS programs, may not even run on faster computers. Particularly when emulating computers which were "closed-box", in which changes to the core of the system were not typical, software may use techniques that depend on specific characteristics of the computer it ran on (e.g. its CPU's speed) and thus precise control of the speed of emulation is important for such applications to be properly emulated.

Input/output (I/O)

[edit]Most emulators do not, as mentioned earlier, emulate the main system bus; each I/O device is thus often treated as a special case, and no consistent interface for virtual peripherals is provided. This can result in a performance advantage, since each I/O module can be tailored to the characteristics of the emulated device; designs based on a standard, unified I/O API can, however, rival such simpler models, if well thought-out, and they have the additional advantage of "automatically" providing a plug-in service through which third-party virtual devices can be used within the emulator. A unified I/O API may not necessarily mirror the structure of the real hardware bus: bus design is limited by several electric constraints and a need for hardware concurrency management that can mostly be ignored in a software implementation.

Even in emulators that treat each device as a special case, there is usually a common basic infrastructure for:

- managing interrupts, by means of a procedure that sets flags readable by the CPU simulator whenever an interrupt is raised, allowing the virtual CPU to "poll for (virtual) interrupts"

- writing to and reading from physical memory, by means of two procedures similar to the ones dealing with logical memory (although, contrary to the latter, the former can often be left out, and direct references to the memory array be employed instead)

Applications

[edit]In preservation

[edit]Emulation is one strategy in pursuit of digital preservation and combating obsolescence. Emulation focuses on recreating an original computer environment, which can be time-consuming and difficult to achieve, but valuable because of its ability to maintain a closer connection to the authenticity of the digital object, operating system, or even gaming platform.[10] Emulation addresses the original hardware and software environment of the digital object, and recreates it on a current machine.[11] The emulator allows the user to have access to any kind of application or operating system on a current platform, while the software runs as it did in its original environment.[12] Jeffery Rothenberg, an early proponent of emulation as a digital preservation strategy states, "the ideal approach would provide a single extensible, long-term solution that can be designed once and for all and applied uniformly, automatically, and in organized synchrony (for example, at every refresh cycle) to all types of documents and media".[13] He further states that this should not only apply to out of date systems, but also be upwardly mobile to future unknown systems.[14] Practically speaking, when a certain application is released in a new version, rather than address compatibility issues and migration for every digital object created in the previous version of that application, one could create an emulator for the application, allowing access to all of said digital objects.

In new media art

[edit]Because of its primary use of digital formats, new media art relies heavily on emulation as a preservation strategy. Artists such as Cory Arcangel specialize in resurrecting obsolete technologies in their artwork and recognize the importance of a decentralized and deinstitutionalized process for the preservation of digital culture. In many cases, the goal of emulation in new media art is to preserve a digital medium so that it can be saved indefinitely and reproduced without error, so that there is no reliance on hardware that ages and becomes obsolete. The paradox is that the emulation and the emulator have to be made to work on future computers.[15]

In future systems design

[edit]Emulation techniques are commonly used during the design and development of new systems. It eases the development process by providing the ability to detect, recreate and repair flaws in the design even before the system is actually built.[16] It is particularly useful in the design of multi-core systems, where concurrency errors can be very difficult to detect and correct without the controlled environment provided by virtual hardware.[17] This also allows the software development to take place before the hardware is ready,[18] thus helping to validate design decisions and give a little more control.

Comparison with simulation

[edit]The word "emulator" was coined in 1963 at IBM[19] during development of the NPL (IBM System/360) product line, using a "new combination of software, microcode, and hardware".[20] They discovered that simulation using additional instructions implemented in microcode and hardware, instead of software simulation using only standard instructions, to execute programs written for earlier IBM computers dramatically increased simulation speed. Earlier, IBM provided simulators for, e.g., the 650 on the 705.[21] In addition to simulators, IBM had compatibility features on the 709 and 7090,[22] for which it provided the IBM 709 computer with a program to run legacy programs written for the IBM 704 on the 709 and later on the IBM 7090. This program used the instructions added by the compatibility feature[23] to trap instructions requiring special handling; all other 704 instructions ran the same on a 7090. The compatibility feature on the 1410[24] only required setting a console toggle switch, not a support program.

In 1963, when microcode was first used to speed up this simulation process, IBM engineers coined the term "emulator" to describe the concept. In the 2000s, it has become common to use the word "emulate" in the context of software. However, before 1980, "emulation" referred only to emulation with a hardware or microcode assist, while "simulation" referred to pure software emulation.[25] For example, a computer specially built for running programs designed for another architecture is an emulator. In contrast, a simulator could be a program which runs on a PC, so that old Atari games can be simulated on it. Purists continue to insist on this distinction, but currently the term "emulation" often means the complete imitation of a machine executing binary code while "simulation" often refers to computer simulation, where a computer program is used to simulate an abstract model. Computer simulation is used in virtually every scientific and engineering domain and Computer Science is no exception, with several projects simulating abstract models of computer systems, such as network simulation, which both practically and semantically differs from network emulation.[26]

Comparison with hardware virtualization

[edit]Hardware virtualization is the virtualization of computers as complete hardware platforms, certain logical abstractions of their components, or only the functionality required to run various operating systems. Virtualization hides the physical characteristics of a computing platform from the users, presenting instead an abstract computing platform.[27][28] At its origins, the software that controlled virtualization was called a "control program", but the terms "hypervisor" or "virtual machine monitor" became preferred over time.[29] Each hypervisor can manage or run multiple virtual machines.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Electronic design automation : synthesis, verification, and test. Laung-Terng Wang, Yao-Wen Chang, Kwang-Ting Cheng. Amsterdam: Morgan Kaufmann/Elsevier. 2009. ISBN 978-0-08-092200-3. OCLC 433173319.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Warick, Mike (April 1988). "MS-DOS Emulation For The 64". Compute!. p. 43. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Linux emulation removed from OpenBSD at version 6.0 https://www.openbsd.org/60.html

- ^ "The Emulation Imitation". Malwarebytes Labs. 17 October 2014. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- ^ "Sony Computer Entertainment America v. Bleem, 214 F. 3d 1022". 9th Circuit 2000. Google Scholar. Court of Appeals (published 4 May 2000). 14 February 2000. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ see Midway Manufacturing Co. v. Artic International, Inc., 574 F.Supp. 999, aff'd, 704 F.2d 1009 (9th Cir 1982) (holding the computer ROM of Pac Man to be a sufficient fixation for purposes of copyright law even though the game changes each time played.) and Article 2 of the Berne Convention

- ^ nba-emu/NanoBoyAdvance, NanoBoyAdvance, 2025-03-12, retrieved 2025-03-13

- ^ mgba-emu/mgba, mGBA, 2025-03-13, retrieved 2025-03-13

- ^ Sky (2025-03-12), skylersaleh/SkyEmu, retrieved 2025-03-13

- ^ "What is emulation?". Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Archived from the original on 2015-09-13. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ van der Hoeven, Jeffrey, Bram Lohman, and Remco Verdegem. "Emulation for Digital Preservation in Practice: The Results." The International Journal of Digital Curation 2.2 (2007): 123–132.

- ^ Muira, Gregory. " Pushing the Boundaries of Traditional Heritage Policy: maintaining long-term access to multimedia content." IFLA Journal 33 (2007): 323-326.

- ^ Rothenberg, Jeffrey (1998). ""Criteria for an Ideal Solution." Avoiding Technological Quicksand: Finding a Viable Technical Foundation for Digital Preservation". Council on Library and Information Resources. Washington, DC. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ Rothenberg, Jeffrey. "The Emulation Solution." Avoiding Technological Quicksand: Finding a Viable Technical Foundation for Digital Preservation. Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources, 1998. Council on Library and Information Resources. 2008. 28 Mar. 2008 https://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/rothenberg/contents.html

- ^ "Echoes of Art: Emulation as preservation strategy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-27. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ Peter Magnusson (2004). "Full System Simulation: Software Development's Missing Link".

- ^ "Debugging and Full System Simulation".

- ^ Vania Joloboff (2009). "Full System Simulation of Embedded Systems" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-09. Retrieved 2012-04-22.

- ^ Pugh, Emerson W. (1995). Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology. MIT. p. 274. ISBN 0-262-16147-8.

- ^ Pugh, Emerson W.; et al. (1991). IBM's 360 and Early 370 Systems. MIT. ISBN 0-262-16123-0. pages 160-161

- ^ Simulation of the IBM 650 on the IBM 705

- ^ "IBM Archives: 7090 Data Processing System (continued)". www-03.ibm.com. 23 January 2003. Archived from the original on March 13, 2005.

- ^ "System Compatibility Operations". Reference Manual IBM 7090 Data Processing System (PDF). March 1962. pp. 65–66. A22-6528-4.

- ^ "System Compatibility Operations". IBM 1410 Principles of Operation (PDF). March 1962. pp. 56–57, 98–100. A22-0526-3.

- ^ Tucker, S. G (1965). "Emulation of large systems". Communications of the ACM. 8 (12): 753–61. doi:10.1145/365691.365931. S2CID 15375675.

- ^ "Network simulation or emulation?". Network World. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Turban, E; King, D.; Lee, J.; Viehland, D. (2008). "19". Electronic Commerce A Managerial Perspective (PDF) (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-21. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ^ "Virtualization in education" (PDF). IBM. October 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Creasy, R.J. (1981). "The Origin of the VM/370 Time-sharing System" (PDF). IBM. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

External links

[edit]Emulator

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins in Computing (1960s–1980s)

The origins of computer emulation trace to the mid-1960s, when hardware manufacturers confronted the challenge of incompatible legacy systems during architectural shifts. IBM's System/360 family, announced on April 7, 1964, addressed this by integrating dedicated emulators—implemented via special hardware and microcode—that enabled execution of programs originally written for disparate predecessors, including the IBM 1401 accounting machines, 1410 and 7010 systems, and scientific 7090 computers.[9] These emulators operated at speeds close to native performance on compatible models, prioritizing seamless migration for enterprise customers reliant on existing software investments rather than full rewrites.[9] This engineering choice stemmed from the economic imperative of unifying IBM's fragmented product lines, which had evolved without standardization since the 1950s, thus averting customer lock-in risks amid rapid technological turnover. Emulation's role expanded in the 1970s as mainframe users grappled with escalating operational costs and the need to sustain aging infrastructure. The IBM System/370, introduced in 1970 as a direct evolutionary successor to the System/360, maintained architectural compatibility but spurred ancillary emulation efforts to port workloads onto smaller, less expensive peripherals or minicomputer hosts, circumventing the expense of full-scale hardware upgrades.[10] Hardware obsolescence accelerated this trend, as components from 1960s-era systems became scarce and unreliable, rendering physical preservation impractical; emulation thus emerged as a pragmatic intermediary, replicating instruction sets and peripherals in software to extend the viability of critical business applications without disrupting data processing pipelines.[11] By decade's end, such techniques underscored emulation's causal utility in mitigating the sunk costs of proprietary architectures, fostering incremental modernization over abrupt overhauls. Into the 1980s, emulation principles began influencing smaller-scale replications amid the proliferation of personal and dedicated systems, though initial applications remained tethered to professional computing needs. Early forays replicated mainframe peripherals and simple dedicated hardware on emerging microcomputers, driven by similar obsolescence pressures as arcade and specialized machines faced decommissioning; this laid groundwork for cost-effective simulation before recreational emulation gained traction.[12] Overall, these decades established emulation not as a novelty but as an essential response to the inexorable decay of bespoke hardware, prioritizing fidelity to original behaviors for sustained operational continuity.[13]Emergence of PC and Console Emulation (1990s)

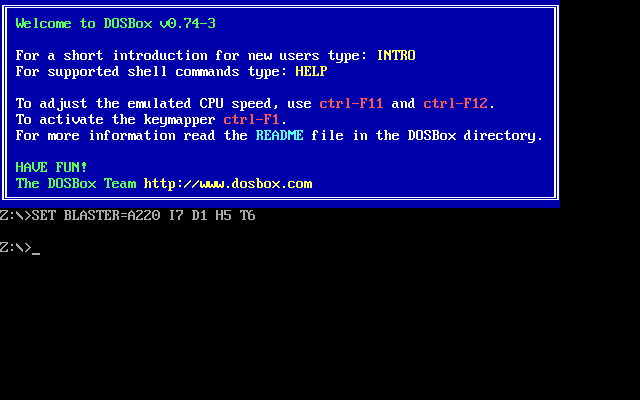

In the mid-1990s, emulation of personal computers and video game consoles experienced rapid growth, driven by substantial increases in CPU performance that enabled real-time execution of emulated code from earlier 8-bit and 16-bit architectures.[14] Personal computers equipped with processors like the Intel Pentium, which by 1995 offered clock speeds exceeding 100 MHz, provided the computational overhead necessary to interpret and replicate the simpler instruction sets and timings of legacy systems without prohibitive slowdowns.[15] Concurrently, the burgeoning internet facilitated the sharing of emulator executables, disassembled code, and game ROM files via bulletin board systems (BBS) and early websites, accelerating dissemination among hobbyists worldwide.[16] Early efforts included cross-platform emulation such as ReadySoft's A-Max II, released in 1990, which allowed Amiga computers to run Macintosh software by incorporating genuine Apple ROMs and emulating compatible hardware behaviors.[17] On personal computers, the Unix Amiga Emulator (UAE) emerged around 1995, providing one of the first software-based replications of Commodore Amiga hardware for Unix-like systems, relying on dynamic recompilation to achieve playable speeds.[18] Console emulation followed closely, with the first notable Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) emulator for PCs, NESticle, debuting on April 3, 1997, as a freeware DOS and Windows application capable of running many commercial titles at full speed on mid-range hardware.[19] Arcade emulation also advanced with the initial release of Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator (MAME) on February 5, 1997, targeting preservation of coin-operated machines through hardware-level simulation.[15] Hobbyist developers, often working independently or in nascent online communities, drove these projects via reverse engineering techniques like disassembly of ROM dumps and logic analysis of hardware signals, compensating for the absence of official technical documentation from manufacturers.[19] This grassroots approach democratized access to obsolete software libraries, circumventing hardware degradation and vendor discontinuation of support, thereby enabling broader archival and playback of titles that might otherwise have been lost to physical media failures or proprietary lock-in.[20] ![E-UAE running Amiga software on Linux][float-right] The proliferation of such tools underscored emulation's role in countering the ephemerality of early digital media, as enthusiasts shared findings on forums and early web ports, fostering iterative improvements in accuracy and compatibility without commercial incentives.[16]Maturation and Mainstream Adoption (2000s–Present)

During the 2000s, emulation matured through expanded support in projects like MAME, which grew from emulating a single arcade game in 1997 to hundreds of systems by the decade's end, prioritizing accurate hardware replication to preserve decaying arcade boards and cabinets.[15][21] This shift aligned with increasing hardware scarcity, as original components failed without manufacturer support, positioning MAME as a archival tool rather than mere gameplay facilitator.[22] Concurrently, NES emulators such as FCEUX—forked and unified in 2006 from earlier FCE Ultra variants—gained traction in modding and speedrunning communities, offering cycle-accurate simulation for tool-assisted speedruns (TAS) that demanded precise frame-by-frame control and input rerecording.[23][24] From 2013 onward, institutional adoption accelerated with the Internet Archive's launch of in-browser emulation via the Emularity framework, enabling direct execution of preserved microcomputer and console software without local installation or ROM dumps.[25] This system, built on JavaScript ports of emulators like MAME and DOSBox, handled millions of user sessions by 2018, expanding to include early Macintosh models and Flash-based games by the early 2020s, thereby democratizing access to obsolete formats amid vanishing physical media.[26][27][28] In the 2020s, emulation's focus sharpened on high-accuracy drivers for obscure systems, such as rare arcade variants and lesser-known consoles, through iterative MAME updates that documented undumped hardware behaviors without revolutionary core technique shifts.[22] These efforts countered hardware obsolescence, where failing components like electrolytic capacitors in 1980s boards rendered originals unplayable, sustaining analytical access for researchers and enthusiasts while metrics from archives indicate sustained high usage for preservation rather than casual play.[27]Types and Classifications

Emulation Fidelity Levels

Emulation fidelity refers to the degree to which an emulator replicates the original hardware's behavior, ranging from high-level approximations that prioritize performance over precision to low-level simulations achieving bit-exact or cycle-exact reproduction. High-level emulation (HLE) abstracts complex hardware components, emulating their functional outputs without simulating internal states or precise timings, which enables faster execution but risks incompatibilities with software reliant on undocumented behaviors.[29][30] In contrast, low-level emulation (LLE), particularly cycle-accurate variants, models hardware interactions at the granularity of individual clock cycles, ensuring causal fidelity by replicating the sequence and duration of operations as they occur on the target system.[31][32] Cycle-accurate emulation demands simulating every machine cycle, including inter-component timings and state updates, to verifiably reproduce phenomena such as glitches, race conditions, and timing-dependent audio or video artifacts that arise from the original hardware's causal dynamics.[33][34] This level of fidelity is essential for applications requiring exact behavioral matching, as higher abstractions often fail to capture emergent effects unexplainable without precise cycle modeling, such as legacy software bugs triggered by subtle hardware interactions.[33][34] To balance fidelity with real-time performance on modern processors, emulators employ varying execution models, including interpreters that decode and execute each instruction sequentially for maximal control over timing, albeit at significant speed costs, versus just-in-time (JIT) compilation or dynamic recompilation, which translate guest code blocks to host-native instructions for acceleration but introduce trade-offs in maintaining cycle precision, particularly for interrupt handling and state synchronization.[35][36] Interpreters facilitate straightforward cycle-accurate stepping by avoiding optimization assumptions that could alter causal sequences, while JIT approaches optimize for throughput, potentially requiring fallback mechanisms to preserve accuracy during timing-critical operations.[35][37]Target System Categories

Emulators are classified by the specific hardware architectures or systems they replicate, with categories reflecting the diversity of target platforms from specialized consumer devices to foundational computing components and communication protocols. This taxonomy emphasizes the hardware scope, such as whether emulation targets a complete machine with peripherals or isolated elements like processors. Video game console emulators constitute the most prominent category, driven by widespread interest in preserving and accessing legacy titles on modern hardware.[38][39] Video game console emulators replicate dedicated gaming hardware, such as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) or Sony PlayStation, enabling execution of ROM image files derived from original cartridges or discs. Their dominance arises from the relatively constrained and well-documented architectures of these systems, which often feature fixed instruction sets and minimal peripheral variation compared to general-purpose computers, simplifying the emulation process. Examples include Mesen for the NES, which supports cycle-accurate replication of the system's PPU and APU, and PCSX2 for the PlayStation 2, handling its Emotion Engine CPU and Graphics Synthesizer. Community-driven development has resulted in hundreds of such projects, far outnumbering those for other targets, as evidenced by repositories like GitHub's emulation topic, where console-focused tools garner the majority of stars and forks.[40][3] CPU-specific emulators, in contrast, target individual processor architectures for instruction set architecture (ISA) translation, without necessarily simulating surrounding hardware like memory controllers or I/O devices. These differ from full-system emulators, which integrate CPU emulation with peripherals for complete machine behavior; for instance, a CPU-only emulator might translate MIPS instructions to x86 on a host, suitable for software porting, whereas full-system variants like QEMU in user-mode emulate the CPU alongside virtualized peripherals when configured for system-mode operation. Examples include Unicorn Engine, which provides lightweight CPU emulation for multiple ISAs including ARM and x86, focusing on dynamic binary analysis rather than holistic hardware replication. This category supports cross-architecture development but lacks the comprehensive peripheral modeling required for running unmodified firmware.[3][40] Terminal emulators replicate the interface and protocol behaviors of legacy text-based terminals, such as VT100 or xterm standards, prioritizing display rendering, keyboard input mapping, and escape sequence handling over precise hardware timing. Unlike gaming emulators, they operate with lower sensitivity to clock cycles, as their primary function is protocol fidelity for command-line interactions rather than real-time synchronization with custom chips. Common implementations include GNOME Terminal and Alacritty, which simulate terminal capabilities within graphical environments to connect to remote shells or local processes.[40] Network emulators simulate communication protocols and link characteristics, such as latency, packet loss, and bandwidth constraints, to test applications under varied conditions without physical infrastructure. They focus on behavioral replication of network elements like routers or end-hosts, often intercepting traffic between real devices, and exhibit reduced emphasis on microsecond-level timing compared to console emulation's frame-rate demands. Examples include the Common Open Research Emulator (CORE), which integrates with Linux kernels to emulate topologies supporting protocols like TCP/IP, and tools like NetEm for Linux-based delay and jitter imposition. These are prevalent in development and quality assurance, where protocol accuracy trumps cycle-exact hardware simulation.[39][41]Specialized Emulators

Specialized emulators target niche domains such as mobile application development, hardware design verification, and distributed system testing, enabling simulation of specific hardware-software interactions without dedicated physical infrastructure. These tools prioritize functional equivalence over broad-spectrum compatibility, often integrating with development environments to facilitate iterative testing and validation. By emulating targeted behaviors—such as sensor inputs in mobile devices or gate-level logic in integrated circuits—they support causal analysis of system dynamics, allowing developers to isolate variables and predict outcomes prior to fabrication or deployment.[42][43] Mobile device emulators, integral to app testing workflows, replicate smartphone and tablet environments to evaluate software performance across virtual hardware configurations. The Android Emulator, bundled with Android Studio since its initial release in 2007 and updated as of September 19, 2024, simulates diverse device profiles including varying screen sizes, CPU architectures, and Android API levels, enabling developers to test applications without procuring multiple physical units.[42] The Android Emulator also supports text input using the host computer's physical keyboard. This is enabled via the 'Keyboard: Enable Keyboard Input' option in the advanced settings during AVD creation or editing, which allows keystrokes from the host keyboard to be sent to the emulated device. This functionality can be combined with hardware profiles that include the 'Input: Has Hardware Keyboard' setting to suppress the on-screen keyboard when a physical keyboard is modeled on the virtual device.[44] Unlike consumer-oriented Android emulators such as BlueStacks, it provides superior privacy and security by avoiding data collection, advertisements, and malware risks; lacks monetization features like in-app purchases or bundled software; offers flexibility to select system images without Google Play Services for maximal privacy or include them for compatibility; and is freely available without commercial incentives.[42] Similarly, Apple's iOS Simulator, embedded in Xcode since version 4.0 in 2011, emulates iOS and iPadOS interfaces on macOS hosts, supporting rapid iteration for UI/UX validation and basic functionality checks, though it abstracts certain hardware features like GPU acceleration for efficiency.[45] These emulators reduce dependency on costly device farms, with empirical usage in CI/CD pipelines demonstrating iteration cycles shortened by up to 50% in controlled development scenarios, as hardware abstraction minimizes procurement and maintenance overhead.[46] In hardware design, FPGA-based emulators address verification challenges for very-large-scale integration (VLSI) and system-on-chip (SoC) prototypes, mapping register-transfer level (RTL) designs onto reconfigurable logic arrays to execute at speeds approaching real-time operation. Cadence Palladium platforms, introduced in the early 2000s and refined for multi-billion-gate capacities, facilitate hardware-software co-verification by interfacing emulated designs with live software stacks, detecting concurrency bugs and timing violations that simulation alone often misses.[43] Synopsys ZeBu systems, similarly FPGA-centric, support in-circuit emulation for advanced nodes, achieving clock rates in the MHz range for complex ASICs and enabling early power estimation through toggling analysis.[47] Such tools causally lower prototyping expenses by deferring tape-out until post-emulation fixes, with industry reports indicating emulation-driven verification cuts physical silicon respins—each costing millions—by validating designs at 10-100x simulation throughput, thereby compressing design timelines from months to weeks.[48][49] Network emulators for distributed systems simulate interconnected nodes and protocols to test scalability and fault tolerance in virtual topologies, executing unmodified application code atop abstracted link layers. Shadow, an open-source discrete-event emulator released in 2013, runs real Linux binaries across emulated wide-area networks, modeling latency, bandwidth constraints, and packet loss to replicate production-like behaviors for applications like peer-to-peer protocols or cloud services.[50] Tools like Kathará, leveraging container orchestration since 2019, emulate multi-host environments via Docker or Kubernetes clusters, supporting protocol stack verification without custom hardware.[51] These platforms enable causal probing of emergent properties in large-scale deployments, such as congestion cascades, reducing the need for expensive testbeds; for instance, emulation facilitates 1000+ node scenarios on commodity servers, accelerating debugging cycles compared to physical clusters that demand synchronized hardware synchronization.[52]Technical Foundations

Core Emulation Techniques

Core emulation techniques center on methods for executing guest system instructions on a host processor, addressing the fundamental challenge of binary incompatibility between architectures. The simplest approach is interpretation, where the emulator fetches an instruction from emulated memory, decodes its opcode to determine the operation, and emulates the effect directly on the host.[53] This per-instruction overhead—arising from repeated fetch-decode cycles—results in significant slowdowns, often by factors of 10 to 1000 relative to native execution, as each guest opcode requires host-side simulation without precompilation.[54] Interpretation's advantages lie in its straightforward implementation and low memory footprint, making it suitable for initial prototyping or systems with irregular instruction flows, though it incurs high computational cost due to the causal bottleneck of decoding every instruction dynamically.[55] To mitigate interpretation's inefficiencies, binary translation recompiles blocks of guest code into host-native equivalents, either statically (ahead-of-time) or dynamically (just-in-time, or JIT). Static translation precompiles entire binaries, optimizing for known code paths but requiring upfront analysis and struggling with self-modifying code common in legacy software.[56] Dynamic binary translation, as implemented in emulators like QEMU, translates and caches code on-the-fly, enabling optimizations such as dead code elimination and register allocation tailored to the host architecture.[57] This yields substantial speedups: JIT-based systems can outperform pure interpretation by 10-100 times on x86 hosts for compute-intensive workloads, as translation amortizes overhead across instruction blocks and leverages host hardware accelerations unavailable in interpretive loops.[58] Empirical benchmarks confirm dynamic translators like QEMU achieve near-native performance for translated kernels, with overheads reduced to under 5% in optimized cases through techniques like trace linking.[55] Hybrid methods further refine efficiency, particularly for systems blending computation and I/O. Threaded interpretation replaces traditional decode-dispatch loops with indirect jumps to threaded code pointers, eliminating redundant opcode fetches and improving branch prediction on modern CPUs, which can yield 20-50% faster dispatch than switch-based interpreters.[59] Co-interpreters extend this by pairing a lightweight host interpreter with guest-specific handlers, offloading I/O-heavy operations to native code while interpreting control flows, thus balancing accuracy and speed in peripherals-dominated emulation.[60] These techniques underpin causal realism in emulation by preserving instruction semantics while minimizing host-side artifacts, though trade-offs persist: translation excels in CPU-bound scenarios but demands complex exception handling to maintain fidelity.[61]System Components and Implementation

The central component of a software emulator is the CPU simulator, which replicates the target processor's architecture by implementing instruction fetch, decode, and execute cycles, often using interpretive or just-in-time compilation methods to translate guest instructions into host machine code.[62] This module maintains the processor's state, including registers, flags, and program counter, while synchronizing with other subsystems to mimic timing-dependent behaviors like interrupts.[63] The memory subsystem emulates the target system's address space through mapping mechanisms that decode reads and writes, handling features such as paging, bank switching, and memory-mapped I/O regions to ensure accurate data access patterns.[64] Bus contention and arbitration are modeled to simulate delays from shared access among components, preventing idealized data flow that would alter software timing.[65] Input/output handling involves simulating peripherals through device models or state machines interfaced via emulated buses, where events like controller inputs or disk accesses are processed asynchronously using queues to manage interrupt priorities and response latencies.[66] This approach allows modular integration of diverse hardware, such as timers or network adapters, by defining protocol-compliant interactions without direct hardware access.[67] Graphics and sound subsystems are typically emulated by interpreting target-specific rendering commands and audio generation logic, then outputting via host APIs like OpenGL for visuals or OpenAL for audio to leverage modern hardware acceleration.[63] Fidelity trade-offs arise in synchronizing emulated frame buffers or waveform synthesis with host rendering pipelines, potentially introducing latency mismatches that affect real-time applications.[68] Modular designs facilitate scalability by isolating these components, enabling developers to swap implementations for different targets or hosts while preserving core emulation logic.[64]Accuracy, Performance, and Challenges

Accuracy Metrics and Trade-offs

Accuracy in emulation is assessed through metrics such as bit-exact output matching, where the emulator produces identical binary data streams to original hardware under controlled inputs; timing precision, which measures adherence to the exact clock cycles and latencies of hardware components; and regression testing, involving comparisons against real hardware behaviors using test ROMs or suites to verify replication of edge cases.[69][33] These criteria enable quantifiable evaluation, distinguishing cycle-accurate emulation—simulating machine cycles with precise timing—from higher-level approximations that abstract hardware for speed but risk behavioral divergences.[32] Trade-offs between accuracy and performance arise from the computational intensity of granular simulation: doubling emulation accuracy typically doubles execution time, as each layer of fidelity requires modeling additional hardware interactions without shortcuts, potentially halving effective performance on equivalent hardware for preservation-grade emulators.[34] While approximations prioritize playability by emulating functional outcomes rather than internal states, leading to faster operation, they introduce unverifiable assumptions about hardware that can alter software-dependent results; cycle-accurate approaches, though resource-heavy, allow direct verification against originals, countering the notion that performance gains inherently undermine faithfulness by ensuring causal chains of hardware events remain intact.[33] Empirical validation highlights these distinctions, as in NES emulation where cycle-accurate implementations reproduce bus conflicts—simultaneous read/write accesses on the same address lines causing data corruption or delays—that manifest as glitches in games like certain unlicensed cartridges or homebrew tests, behaviors absent or inconsistently handled in less precise emulators relying on abstracted bus models.[70] Such inaccuracies propagate causally: minor timing deviations can cascade into erroneous AI decisions, physics interactions, or rendering artifacts in software exploiting undocumented hardware quirks, underscoring that approximations, despite speed advantages, may fabricate non-original outcomes rather than merely accelerating truthful ones.[69] For critical uses like archival verification, these metrics confirm that accuracy's costs yield reproducible fidelity, not mere slowdown.[34]Optimization Methods

Optimization in emulation prioritizes exploiting host system capabilities, such as multi-core processors and vector units, to accelerate execution while preserving the exact semantics of the emulated hardware. These methods avoid altering the guest system's behavior, instead focusing on efficient translation and parallel execution of independent components. Dynamic recompilation and caching mechanisms form the core of CPU emulation speedup, enabling near-native performance for complex instruction sets. Just-in-time (JIT) compilation, often implemented as dynamic recompilation, translates blocks of emulated instructions into host-native code at runtime rather than interpreting them cycle-by-cycle. This approach caches recompiled code for "hot" paths—frequently executed sequences—reducing overhead from repeated translation and enabling sustained high performance. In the PCSX2 PlayStation 2 emulator, the dynamic recompiler emits and stores translated x86 instruction blocks for reuse, dramatically outperforming pure interpretation by executing guest code as optimized native routines. Similarly, Dolphin emulator's JIT compiler converts PowerPC instructions from GameCube and Wii systems into host code, with cache management adjustable via source modifications for larger code buffers on high-memory systems. Parallelization leverages multi-core host CPUs by isolating emulation of loosely coupled subsystems into separate threads, such as decoupling CPU core simulation from graphics rendering or audio synthesis. This allows concurrent processing where dependencies permit, synchronized via timestamps or locks to maintain causal ordering without fidelity loss. For example, in a Super Nintendo emulator, rendering pipelines can be multithreaded to distribute pixel processing across cores, improving throughput on systems with multiple threads while the main emulation loop handles CPU and timing. Audio subsystems, often independent of frame updates, run in dedicated threads to generate samples asynchronously, preventing bottlenecks in real-time output. Vectorization employs SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) extensions in modern CPUs to perform bulk operations efficiently, particularly in graphics emulation where repetitive tasks like texture filtering or vertex transformations benefit from parallel data handling. Host instructions such as SSE or AVX process multiple pixels or vectors simultaneously, accelerating emulated GPU workloads without emulating the guest's scalar operations differently. These optimizations collectively enable full-speed emulation; for instance, 1990s consoles like the Super Nintendo achieve 60 FPS on 2020s-era hardware using emulators like those in EmuDeck setups, running without speed hacks or accuracy trade-offs on standard multi-core PCs.Persistent Technical Hurdles

Accurate emulation of hardware timing demands cycle-precise synchronization across all emulated components, such as CPUs, peripherals, and buses, to replicate the original system's clock-driven behaviors; however, host platforms with disparate clock rates introduce unavoidable overhead, as the emulator must insert delays, busy-wait, or context-switch frequently to avoid desynchronizing events like interrupts or DMA transfers. This process exacerbates race conditions inherent in hardware, where outcomes depend on microsecond-level ordering of concurrent accesses—simulating these requires enforcing host-level barriers that serialize execution and prevent the host's native speed advantages from fully materializing, often resulting in emulation speeds far below real-time even on high-end hardware.[33][71] Undocumented hardware behaviors pose ongoing barriers, as many legacy systems rely on proprietary or unpublicized features—like atypical opcode effects, glitch-prone signal timings, or peripheral side-effects—that are absent from official datasheets and must be inferred via reverse engineering techniques such as logic analysis or real-hardware disassembly. These elements, often critical for software compatibility, demand iterative validation against physical prototypes, yet incomplete replication persists due to the black-box nature of such discovery, leading to edge-case failures in emulated environments that do not manifest on authentic hardware.[72][73] Scaling emulation to multi-core or networked legacy architectures amplifies serialization bottlenecks on single-host setups, where simulating parallel processor interactions, shared memory coherency protocols, or distributed latencies forces sequential processing of interdependent events despite the host's multi-threading capabilities. For instance, emulating bus contention or packet routing in systems like early multi-processor workstations requires modeling non-deterministic ordering that resists efficient parallelization, constraining overall throughput and fidelity as system complexity increases.[74][75] Fundamentally, software-based hardware emulation incurs interpretive overhead that grows supralinearly with target intricacy, as each emulated instruction or state transition demands host resources without the specialized circuits of the original—empirical benchmarks show orders-of-magnitude efficiency losses, limiting bit-perfect replication to simpler systems while complex ones approach host computational ceilings due to the absence of isomorphic acceleration.[76][77]Applications

Preservation and Archiving

Emulation facilitates the long-term access to obsolete software by replicating the behavior of legacy hardware and operating environments on contemporary systems, thereby mitigating the risks posed by physical media degradation such as disc rot, battery leakage in cartridges, and hardware obsolescence.[13][20] This approach preserves the original digital artifacts in their native formats without necessitating repeated reads from deteriorating storage media, which can accelerate failure in magnetic tapes, optical discs, or volatile memory backups.[20] Institutions like the Internet Archive have leveraged emulation to maintain playable archives of software, including over 250,000 emulated executions across platforms such as MS-DOS and early consoles, enabling users to interact with titles otherwise inaccessible due to failed original hardware.[27] For video games, emulation sustains functionality for the majority of archived titles where physical cartridges exhibit failure rates exceeding 20-30% from component decay, such as capacitor leaks or ROM corrosion, contrasting with the near-100% uptime achievable on maintained emulator implementations for compatible software.[78] This capability counters the abandonment of unprofitable legacy titles by publishers, who re-release only about 13% of pre-2010 games commercially, ensuring empirical continuity of software histories that would otherwise vanish through entropy and disuse.[78][13] However, emulation's preservation efficacy depends on proactive maintenance of emulator codebases, as unupdated implementations risk "software rot" through accumulated bugs, deprecated dependencies, or incompatibility with evolving host operating systems, potentially rendering preserved environments inoperable over decades without sustained development.[20] Over-reliance on emulation without parallel strategies, such as migration to standardized formats, can propagate these vulnerabilities, underscoring the need for verifiable accuracy testing and community-driven updates to avert cascading failures in archival access.[79]Development and Testing

Emulators play a critical role in firmware development by simulating legacy hardware interfaces, allowing developers to test compatibility and functionality for new systems without access to rare or obsolete physical components. This approach is particularly valuable in hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing, where firmware interacts with emulated real-world conditions to validate behavior under controlled scenarios.[80][81] In electronic design automation (EDA), FPGA-based hardware emulators enable pre-silicon verification of application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), bridging the gap between simulation and physical prototyping. Systems like Siemens' Veloce CS integrate emulation with prototyping to handle designs up to billions of gates, providing faster validation cycles than pure software simulation by leveraging reconfigurable hardware for real-time execution.[82] This acceleration supports iterative debugging and reduces time-to-market for complex chips, with emulation offering performance gains through modular, scalable deployments.[83] For cross-platform quality assurance (QA), emulators replicate diverse hardware environments, enabling comprehensive testing without maintaining extensive physical labs, which lowers expenses on device procurement and logistics. In mobile and embedded software development, this facilitates early defect detection across configurations, avoiding the higher costs of real-device fleets that can exceed emulation setups by factors tied to hardware depreciation and scalability limits.[84][85] Despite these advantages, emulation's fidelity issues, such as incomplete peripheral models for sensors or interfaces, can produce false positives where software passes in simulation but fails on actual hardware due to unmodeled interactions or timing discrepancies. These gaps necessitate hybrid approaches combining emulation with real-device validation to mitigate risks in critical systems.[86][87]Consumer Entertainment

Emulators facilitate consumer entertainment primarily through retro gaming, allowing users to execute dumped ROM images of legacy video games on contemporary personal computers and mobile devices, bypassing the need for aging or scarce original hardware. This practice surged in popularity during the 2010s with open-source projects like RetroArch, which integrates multiple emulator cores and supports enhancements for modern displays. The global retro video game market, encompassing emulation-driven play, reached an estimated $2.5 billion in annual value by 2025, reflecting sustained consumer interest in nostalgic titles from the 1980s and 1990s.[88] Users commonly apply graphical post-processing techniques, such as shaders for pixel art upscaling and CRT scanline simulation, to mitigate visual artifacts when rendering low-resolution games on high-definition screens. These enhancements, available in emulators like those within RetroArch, enable integer scaling to 4K resolutions and anti-aliasing, improving accessibility and aesthetic appeal without requiring physical cartridge restoration or specialized CRT televisions. For instance, interpolation shaders smooth 2D sprites while preserving retro fidelity, allowing gameplay at frame rates and input latencies comparable to or exceeding original systems.[89][90] Empirical assessments suggest that consumer emulation for nostalgia does not materially erode modern game sales, as retro play correlates with increased purchases of re-releases and merchandise rather than substitution. Legal analyses, including court evaluations of emulator impacts, have noted the unlikelihood of negative effects on primary market revenues, attributing sustained retro hardware and software demand to complementary collector behaviors despite decades of emulation availability.[8] Criticisms center on emulation's role in enabling unauthorized ROM acquisition and distribution via torrent sites and forums, which circumvents copyright protections even if emulator software itself remains legal. While dumping ROMs from owned physical media constitutes a permissible personal backup under certain jurisdictions, widespread consumer practices deviate from this, fostering piracy ecosystems that publishers like Nintendo actively litigate against through takedown actions. Proponents counter that self-dumping mitigates infringement risks, though enforcement challenges persist due to the decentralized nature of user-generated dumps.[91][7][92]Research and Innovation

Emulation facilitates reverse engineering of legacy firmware in security research, allowing analysts to identify vulnerabilities without physical hardware. For instance, firmware re-hosting techniques enable the execution of extracted binaries in emulated environments to detect flaws such as buffer overflows or authentication bypasses in outdated embedded systems.[93] Tools like QEMU and Unicorn Engine support this by simulating processor architectures and peripherals, overcoming challenges in binary translation and device modeling.[93] In a 2023 analysis of D-Link routers, researchers emulated firmware to achieve debuggable interfaces, exposing hardware-specific exploits that physical disassembly alone could not reveal.[94] In historical computing studies, emulation supports reproducible experiments on extinct architectures, such as 1970s minicomputers or early microprocessors no longer manufacturable. By replicating instruction sets and memory models, projects emulate systems like the PDP-11 to execute original software, enabling verification of historical algorithms or protocol behaviors under controlled conditions.[20] This approach has been applied in academic frameworks for testing emulation services, where virtualized environments process legacy datasets to study computational evolution without risking artifact degradation.[95] Such methods ensure empirical fidelity to original timings and outputs, aiding causal analysis of software-hardware interactions in pre-1980s systems. Emulated environments contribute to AI research by generating synthetic datasets for training reinforcement learning models, particularly in simulated legacy games or control systems. For example, Atari console emulators provide deterministic state transitions for policy optimization, allowing scalable experiments on decision-making under uncertainty.[96] However, accuracy gaps—such as approximations in cycle timing or peripheral emulation—can introduce discrepancies, hindering precise causal inference in behavioral studies of timing-sensitive processes like network protocols or real-time firmware responses.[93] These limitations necessitate validation against hardware traces, as interpretive emulation may alter emergent behaviors critical for inferring original causal chains.[97]Legal and Ethical Dimensions

Copyright Infringement and IP Protection

Emulator software developed through clean-room reverse engineering, which avoids direct copying of proprietary code, does not inherently infringe copyright, as established by the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court's 2000 ruling in Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc. v. Connectix Corp., where intermediate copying during development of a PlayStation emulator was deemed fair use due to its transformative nature and lack of market harm to Sony's console sales.[98] This precedent affirms that emulation as a functional replication of hardware behavior respects intellectual property boundaries when no protected elements are appropriated.[99] In contrast, the unauthorized distribution or acquisition of ROM files—digital copies of game software—or BIOS firmware constitutes direct copyright infringement, as these are protected works whose replication and sharing exceed personal backups from lawfully owned media. BIOS files, as copyrighted console firmware, may be legally dumped from personally owned hardware for personal, archival backups, though copying between emulation devices exists in a legal gray area and may violate copyright laws, with users advised to proceed at their own discretion.[100][101][7] Intellectual property holders like Nintendo have pursued legal action against emulator projects involving circumvention tools rather than the emulation cores themselves; for instance, in February 2024, Nintendo sued Yuzu's developers, Tropic Haze LLC, alleging facilitation of piracy through the distribution of encryption keys that bypassed Switch console protections, resulting in a $2.4 million settlement, permanent injunction, and project shutdown by March 2024.[102][103] A parallel voluntary cessation occurred with Ryujinx, another Switch emulator, amid similar pressures, underscoring enforcement against tools enabling illegal decryption over the legality of compatibility software.[104] Such actions prioritize protecting proprietary encryption under laws like the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which prohibits trafficking in circumvention devices, thereby safeguarding revenue streams from licensed content distribution.[105] While IP owners assert that emulation enables widespread piracy eroding sales, empirical evidence establishing a direct causal link remains absent; legal analyses, including those from the Connectix case, have noted the unlikelihood of significant market displacement, with emulation often serving owned or preserved copies rather than substituting purchases.[8] Creating personal dumps from owned hardware for archival purposes aligns with property rights without distribution, paralleling software backup exceptions, though mass sharing of such files violates exclusivity.[7] Excessive reliance on anti-circumvention claims can stifle innovation, as clean-room methods—validated in precedents like Sega Enterprises Ltd. v. Accolade, Inc. (1992)—enable competitive interoperability without appropriating source code, potentially fostering backward compatibility markets that benefit consumers and original creators through renewed interest.[106]Reverse Engineering and Fair Use Debates

Reverse engineering of proprietary hardware and software interfaces constitutes a core practice in emulator development to achieve functional compatibility, often defended as fair use under U.S. copyright law when aimed at interoperability rather than direct replication of expressive elements. In the landmark case Sega Enterprises Ltd. v. Accolade, Inc. (977 F.2d 1510, 9th Cir. 1992), the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Accolade's disassembly of Sega Genesis ROMs to identify undocumented compatibility requirements for independent game cartridges qualified as fair use, emphasizing the pro-competitive benefits of such analysis without substantial market harm to Sega's works.[107] This precedent established that intermediate copying during disassembly for non-expressive functional insights does not infringe copyright, provided the resulting work copies only necessary interface specifications.[108] The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) of 1998 introduced tensions by prohibiting circumvention of technological protection measures (TPMs) encircling copyrighted works, potentially complicating reverse engineering even for legitimate purposes like emulation. Section 1201(f) carves out a narrow exemption permitting circumvention solely for achieving interoperability with independently created software, but only after failed good-faith efforts to obtain interface information and without impairing TPM effectiveness against infringement.[109] Triennial rulemaking by the Librarian of Congress has granted broader exemptions since 2003 for preservation of obsolete software formats by qualified institutions, allowing circumvention to enable archival access without commercial exploitation, though these do not explicitly cover non-institutional emulator development.[110] Emulator communities rely on reverse engineering to uncover undocumented hardware behaviors and timing idiosyncrasies critical for cycle-accurate simulation, enabling faithful reproduction of original system performance without appropriating proprietary code. Such efforts typically involve clean-room implementation, where observed functional specifications inform original code written from scratch, avoiding verbatim copying.[8] Critics, including some intellectual property holders, contend that reverse engineering for emulators inherently facilitates piracy by providing a platform for unauthorized game ROMs, potentially undermining original sales.[111] This view overlooks the standard emulator model requiring users to supply legally obtained ROMs dumped from owned media, which imposes ownership verification and limits widespread infringement absent separate ROM distribution; empirical patterns show emulators persisting alongside legal ROM acquisition methods like official re-releases, without causal evidence of net revenue displacement attributable to the emulator itself rather than independent piracy channels.[8][108]Litigation and Industry Actions

In March 2024, Nintendo settled a lawsuit against Tropic Haze LLC, developers of the Yuzu Nintendo Switch emulator, for $2.4 million in damages; the agreement required the permanent cessation of Yuzu's development, distribution, and source code availability.[112] The suit alleged that Yuzu facilitated widespread piracy by enabling early access to circumvention tools and unauthorized game copies, though Nintendo's claims centered on violations of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) rather than emulation software alone.[102] In October 2024, the Ryujinx Switch emulator team announced a voluntary shutdown following direct pressure from Nintendo of America on its lead developer, halting all further work without a formal lawsuit or settlement.[113] Nintendo's intellectual property counsel stated in January 2025 that emulation is not inherently illegal, provided it avoids facilitating piracy or circumventing technological protections; however, emulators cross into illegality when they incorporate or promote unauthorized code extraction or distribution.[114] This stance aligns with industry patterns where prosecutions target "reach" applications—emulators bundled with or linking to illegal ROMs—rather than standalone software lacking such features, with historical data showing minimal successful actions against pure emulators lacking piracy tools.[104] Earlier precedents include Atari's 1980s suits against third-party developers like Activision for reverse-engineering hardware to create compatible games, which courts treated as trade secret misappropriation rather than outright emulation bans; these cases established limits on disassembly for compatibility but did not directly prosecute software emulators, which were nascent at the time.[115] In modern esports, organizers such as Riot Games have banned emulators in titles like Wild Rift since August 2025 to preserve competitive fairness, citing advantages from keyboard/mouse inputs and macro automation unavailable on native mobile hardware.[116] Such enforcement actions have demonstrably deterred emulator development, as evidenced by the exodus of talent from projects like Yuzu and Ryujinx, thereby hindering archival efforts for aging software that borders on public domain status due to expired licensing or hardware obsolescence.[117]Comparisons with Analogous Technologies

Versus Simulation