Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Computer data storage

View on WikipediaIt has been suggested that Data at rest be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since March 2025. |

| Computer memory and data storage types |

|---|

| Volatile |

| Non-volatile |

Computer data storage or digital data storage is the retention of digital data via technology consisting of computer components and recording media. Digital data storage is a core function and fundamental component of computers.[1]: 15–16

Generally, the faster and volatile storage components are referred to as "memory", while slower persistent components are referred to as "storage". This distinction was extended in the Von Neumann architecture, where the central processing unit (CPU) consists of two main parts: The control unit and the arithmetic logic unit (ALU). The former controls the flow of data between the CPU and memory, while the latter performs arithmetic and logical operations on data. In practice, almost all computers use a memory hierarchy,[1]: 468–473 which puts memory close to the CPU and storage further away.

In modern computers, hard disk drives (HDDs) or solid-state drives (SSDs) are usually used as storage.

Data

[edit]A modern digital computer represents data using the binary numeral system. The memory cell is the fundamental building block of computer memory, storing stores one bit of binary information that can be set to store a 1, reset to store a 0, and accessed by reading the cell.[2][3]

Text, numbers, pictures, audio, and nearly any other form of information can be converted into a string of bits, or binary digits, each of which has a value of 0 or 1. The most common unit of storage is the byte, equal to 8 bits. Digital data comprises the binary representation of a piece of information, often being encoded by assigning a bit pattern to each character, digit, or multimedia object. Many standards exist for encoding (e.g. character encodings like ASCII, image encodings like JPEG, and video encodings like MPEG-4).

Encryption

[edit]For security reasons, certain types of data may be encrypted in storage to prevent the possibility of unauthorized information reconstruction from chunks of storage snapshots. Encryption in transit protects data as it is being transmitted.[4]

Compression

[edit]Data compression methods allow in many cases (such as a database) to represent a string of bits by a shorter bit string ("compress") and reconstruct the original string ("decompress") when needed. This utilizes substantially less storage (tens of percent) for many types of data at the cost of more computation (compress and decompress when needed). Analysis of the trade-off between storage cost saving and costs of related computations and possible delays in data availability is done before deciding whether to keep certain data compressed or not.

Vulnerability and reliability

[edit]Distinct types of data storage have different points of failure and various methods of predictive failure analysis. Vulnerabilities that can instantly lead to total loss are head crashing on mechanical hard drives and failure of electronic components on flash storage.

Redundancy

[edit]Redundancy allows the computer to detect errors in coded data (for example, a random bit flip due to random radiation) and correct them based on mathematical algorithms. The cyclic redundancy check (CRC) method is typically used in communications and storage for error detection. Redundancy solutions include storage replication, disk mirroring and RAID (Redundant Array of Independent Disks).

Error detection

[edit]

Impending failure on hard disk drives is estimable using S.M.A.R.T. diagnostic data that includes the hours of operation and the count of spin-ups, though its reliability is disputed.[5] The health of optical media can be determined by measuring correctable minor errors, of which high counts signify deteriorating and/or low-quality media. Too many consecutive minor errors can lead to data corruption. Not all vendors and models of optical drives support error scanning.[6]

Architecture

[edit]Without a significant amount of memory, a computer would only be able to perform fixed operations and immediately output the result, thus requiring hardware reconfiguration for a new program to be run. This is often used in devices such as desk calculators, digital signal processors, and other specialized devices. Von Neumann machines differ in having a memory in which operating instructions and data are stored,[1]: 20 such that they do not need to have their hardware reconfigured for each new program, but can simply be reprogrammed with new in-memory instructions. They also tend to be simpler to design, in that a relatively simple processor may keep state between successive computations to build up complex procedural results. Most modern computers are von Neumann machines.

Storage and memory

[edit]In contemporary usage, the term "storage" typically refers to a subset of computer data storage that comprises storage devices and their media not directly accessible by the CPU, that is, secondary or tertiary storage. Common forms of storage include hard disk drives, optical disc drives, and non-volatile devices (i.e. devices that retain their contents when the computer is powered down).[7] On the other hand, the term "memory" is used to refer to semiconductor read-write data storage, typically dynamic random-access memory (DRAM). Dynamic random-access memory is a form of volatile memory that also requires the stored information to be periodically reread and rewritten, or refreshed; static RAM (SRAM) is similar to DRAM, albeit it never needs to be refreshed as long as power is applied.

In contemporary usage, the memory hierarchy of primary storage and secondary storage in some uses refer to what was historically called, respectively, secondary storage and tertiary storage.[8]

Primary

[edit]

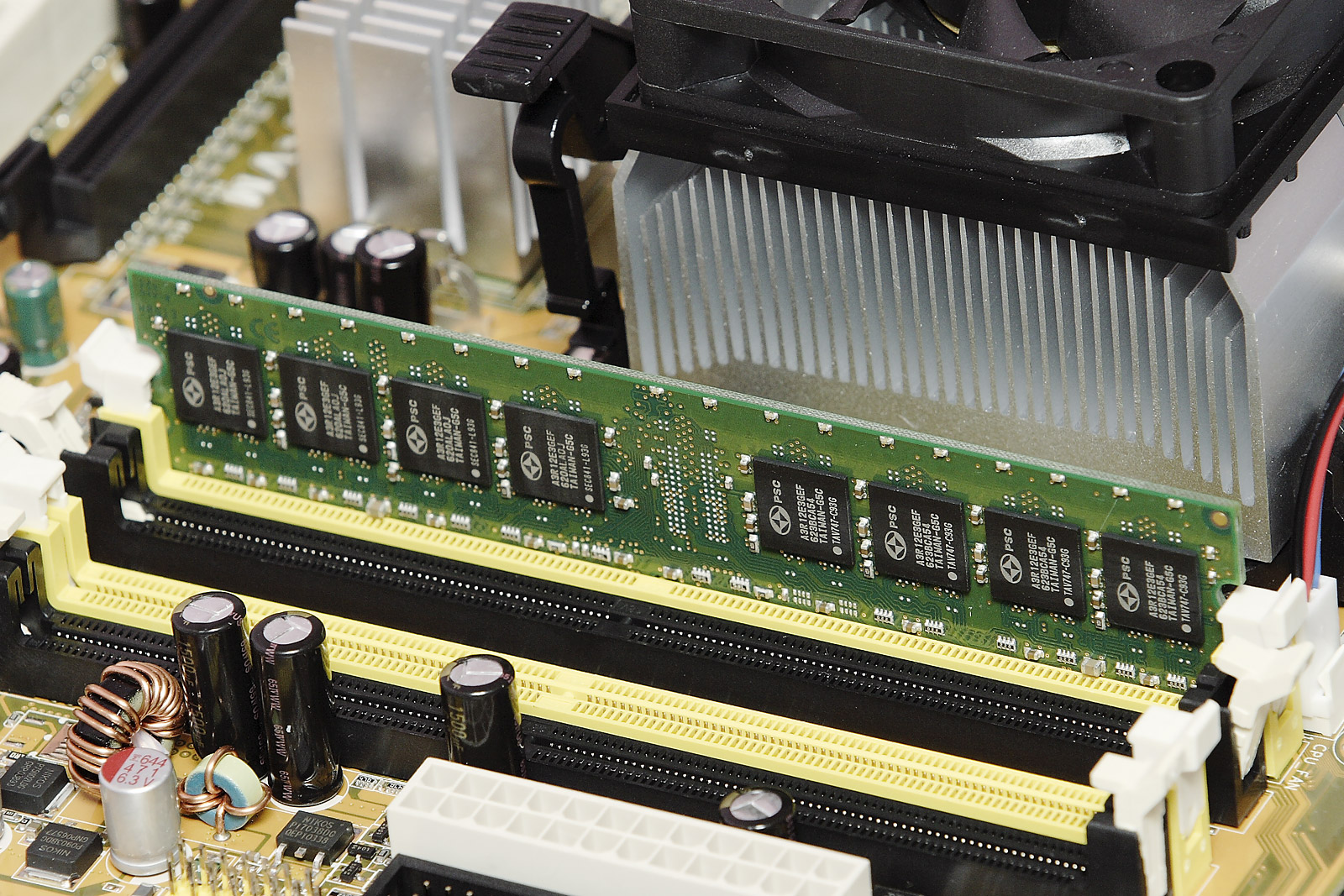

Primary storage (also known as main memory, internal memory, or prime memory), often referred to simply as memory, is storage directly accessible to the CPU. The CPU continuously reads instructions stored there and executes them as required. Any data actively operated on is also stored there in a uniform manner. Historically, early computers used delay lines, Williams tubes, or rotating magnetic drums as primary storage. By 1954, those unreliable methods were mostly replaced by magnetic-core memory. Core memory remained dominant until the 1970s, when advances in integrated circuit technology allowed semiconductor memory to become economically competitive.

This led to modern random-access memory, which is small-sized, light, and relatively expensive. RAM used for primary storage is volatile, meaning that it loses the information when not powered. Besides storing opened programs, it serves as disk cache and write buffer to improve both reading and writing performance. Operating systems borrow RAM capacity for caching so long as it's not needed by running software.[9] Spare memory can be utilized as RAM drive for temporary high-speed data storage. Besides main large-capacity RAM, there are two more sub-layers of primary storage:

- Processor registers are the fastest of all forms of data storage, being located inside the processor, with each register typically holding a word of data (often 32 or 64 bits). CPU instructions instruct the arithmetic logic unit to perform various calculations or other operations on this data.

- Processor cache is an intermediate stage between faster registers and slower main memory, being faster than main memory but with much less capacity. Multi-level hierarchical cache setup is also commonly used, such that primary cache is the smallest and fastest, while secondary cache is larger and slower.

Primary storage, including ROM, EEPROM, NOR flash, and RAM,[10] is usually byte-addressable. Such memory is directly or indirectly connected to the central processing unit via a memory bus, comprising an address bus and a data bus. The CPU firstly sends a number called the memory address through the address bus that indicates the desired location of data. Then it reads or writes the data in the memory cells using the data bus. Additionally, a memory management unit (MMU) is a small device between CPU and RAM recalculating the actual memory address. Memory management units allow for memory management; they may, for example, provide an abstraction of virtual memory or other tasks.

BIOS

[edit]Non-volatile primary storage contains a small startup program (BIOS) is used to bootstrap the computer, that is, to read a larger program from non-volatile secondary storage to RAM and start to execute it. A non-volatile technology used for this purpose is called read-only memory (ROM). Most types of "ROM" are not literally read only but are difficult and slow to write to. Some embedded systems run programs directly from ROM, because such programs are rarely changed. Standard computers largely do not store many programs in ROM, apart from firmware, and use large capacities of secondary storage.

Secondary

[edit]Secondary storage (also known as external memory or auxiliary storage) differs from primary storage in that it is not directly accessible by the CPU. Computers use input/output channels to access secondary storage and transfer the desired data to primary storage. Secondary storage is non-volatile, retaining data when its power is shut off. Modern computer systems typically have two orders of magnitude more secondary storage than primary storage because secondary storage is less expensive.

In modern computers, hard disk drives (HDDs) or solid-state drives (SSDs) are usually used as secondary storage. The access time per byte for HDDs or SSDs is typically measured in milliseconds, while the access time per byte for primary storage is measured in nanoseconds. Rotating optical storage devices, such as CD and DVD drives, have even longer access times. Other examples of secondary storage technologies include USB flash drives, floppy disks, magnetic tape, paper tape, punched cards, and RAM disks.

To reduce the seek time and rotational latency, secondary storage, including HDD, ODD and SSD, are transferred to and from disks in large contiguous blocks. Secondary storage is addressable by block; once the disk read/write head on HDDs reaches the proper placement and the data, subsequent data on the track are very fast to access. Another way to reduce the I/O bottleneck is to use multiple disks in parallel to increase the bandwidth between primary and secondary memory, for example, using RAID.[11]

Secondary storage is often formatted according to a file system format, which provides the abstraction necessary to organize data into files and directories, while also providing metadata describing the owner of a certain file, the access time, the access permissions, and other information. Most computer operating systems use the concept of virtual memory, allowing the utilization of more primary storage capacity than is physically available in the system. As the primary memory fills up, the system moves the least-used chunks (pages) to a swap file or page file on secondary storage, retrieving them later when needed.

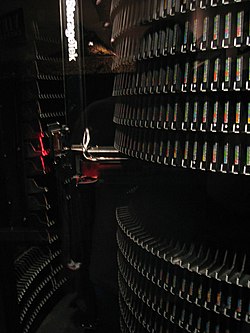

Tertiary

[edit]

Tertiary storage or tertiary memory typically involves a robotic arm which mounts and dismount removable mass storage media from a catalog database into a storage device according to the system's demands. It is primarily used for archiving rarely accessed information, since it is much slower than secondary storage (e.g. 5–60 seconds vs. 1–10 milliseconds). This is primarily useful for extraordinarily large data stores, accessed without human operators. Typical examples include tape libraries, optical jukeboxes, and massive arrays of idle disks (MAID). Tertiary storage is also known as nearline storage because it is "near to online".[12] Hierarchical storage management is an archiving strategy involving automatically migrating long-unused files from fast hard disk storage to libraries or jukeboxes.

Offline

[edit]Offline storage is computer data storage on a medium or a device that is not under the control of a processing unit.[13] The medium is recorded, usually in a secondary or tertiary storage device, and then physically removed or disconnected. Unlike tertiary storage, it cannot be accessed without human interaction. It is used to transfer information since the detached medium can easily be physically transported. In modern personal computers, most secondary and tertiary storage media are also used for offline storage.

Network connectivity

[edit]A secondary or tertiary storage may connect to a computer utilizing computer networks. This concept does not pertain to the primary storage.

- Direct-attached storage (DAS) is a traditional mass storage, that does not use any network.

- Network-attached storage (NAS) is mass storage attached to a computer which another computer can access at file level over a local area network, a private wide area network, or in the case of online file storage, over the Internet. NAS is commonly associated with the NFS and CIFS/SMB protocols.

- Storage area network (SAN) is a specialized network, that provides other computers with storage capacity. SAN is commonly associated with Fibre Channel networks.

Cloud

[edit]Cloud storage is based on highly virtualized infrastructure.[14] A subset of cloud computing, it has particular cloud-native interfaces, near-instant elasticity and scalability, multi-tenancy, and metered resources. Cloud storage services can be used from an off-premises service or deployed on-premises.[15]

Deployment models

[edit]Cloud deployment models define the interactions between cloud providers and customers.[16]

- Private clouds, for example, are used in cloud security to mitigate the increased attack surface area of outsourcing data storage.[17] A private cloud is cloud infrastructure operated solely for a single organization, whether managed internally or by a third party, or hosted internally or externally.[18]

- Hybrid cloud storage are another cloud security solution, involving storage infrastructure that uses a combination of on-premises storage resources with cloud storage. The on-premises storage is usually managed by the organization, while the public cloud storage provider is responsible for the management and security of the data stored in the cloud.[19][20] Using a hybrid model allows data to be ingested in an encrypted format where the key is held within the on-premise infrastructure and can limit access to the use of on-premise cloud storage gateways, which may have options to encrypt the data prior to transfer.[21]

- Cloud services are considered "public" when they are delivered over the public Internet.[22]

- A virtual private cloud (VPC) is a pool of shared resources within a public cloud that provides a certain level of isolation between the different users using the resources. VPCs achieve user isolation through the allocation of a private IP subnet and a virtual communication construct (such as a VLAN or a set of encrypted communication channels) between users as welll as the use of a virtual private network (VPN) per VPC user, securing, by means of authentication and encryption, the remote access of the organization to its VPC resources.[citation needed]

Types

[edit]There are three types of cloud storage:

- Object storage[23][24]

- File storage

- Block-level storage is a concept in cloud-hosted data persistence where cloud services emulate the behaviour of a traditional block device, such as a physical hard drive,[25] where storage is organised as blocks. Block-level storage differs from object stores or 'bucket stores' or to cloud databases. These operate at a higher level of abstraction and are able to work with entities such as files, documents, images, videos or database records.[26] At one time, block-level storage was provided by SAN, and NAS provided file-level storage.[27] With the shift from on-premises hosting to cloud services, this distinction has shifted.[28]

Characteristics

[edit]

Storage technologies at all levels of the storage hierarchy can be differentiated by evaluating certain core characteristics as well as measuring characteristics specific to a particular implementation. These core characteristics are:

- Volatility

- An uninterruptible power supply (UPS) can be used to give a computer a brief window of time to move information from primary volatile storage into non-volatile storage before the batteries are exhausted. Some systems, for example EMC Symmetrix, have integrated batteries that maintain volatile storage for several minutes.

- Mutability

- Storage can be classified into read/write, slow-write/fast-read (e.g. CD-RW, SSD), write-once/read-many or WORM (e.g. programmable read-only memory, CD-R), read-only storage (e.g. mask ROM ICs, CD-ROM).

- Accessibility

- Types of access include random access and sequential access. In random access, any location in storage can be accessed at any moment in approximately the same amount of time. In sequential access, the accessing of pieces of information will be in a serial order, one after the other; therefore the time to access a particular piece of information depends upon which piece of information was last accessed.

- Addressability

- Storage can be location accessible (i.e. selected with its numerical memory address), file addressable, or content-addressable.

- Capacity and density

- Performance

- Storage performance metrics include latency, throughput, granularity and reliability.

- Energy

- Low capacity solid-state drives have no moving parts and consume less power than hard disks.[31][32][33] Also, memory may use more power than hard disks.[33] Large caches, which are used to avoid hitting the memory wall, may also consume a large amount of power.

- Security[34]

| Characteristic | Hard disk drive | Optical disc | Flash memory | Random-access memory | Linear tape-open |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Magnetic disk | Laser beam | Semiconductor | Magnetic tape | |

| Volatility | No | No | No | Volatile | No |

| Random access | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Latency (access time) | ~15 ms (swift) | ~150 ms (moderate) | None (instant) | None (instant) | Lack of random access (very slow) |

| Controller | Internal | External | Internal | Internal | External |

| Failure with imminent data loss | Head crash | — | Circuitry | — | |

| Error detection | Diagnostic (S.M.A.R.T.) | Error rate measurement | Indicated by downward spikes in transfer rates | (Short-term storage) | Unknown |

| Price per space | Low | Low | High | Very high | Very low (but expensive drives) |

| Price per unit | Moderate | Low | Moderate | High | Moderate (but expensive drives) |

| Main application | Mid-term archival, routine backups, server, workstation storage expansion | Long-term archival, hard copy distribution | Portable electronics; operating system | Real-time | Long-term archival |

Media

[edit]Semiconductor

[edit]Semiconductor memory uses semiconductor-based integrated circuit (IC) chips to store information. Data are typically stored in metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) memory cells. A semiconductor memory chip may contain millions of memory cells, consisting of tiny MOS field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) and/or MOS capacitors. Both volatile and non-volatile forms of semiconductor memory exist, the former using standard MOSFETs and the latter using floating-gate MOSFETs.

In modern computers, primary storage almost exclusively consists of dynamic volatile semiconductor random-access memory (RAM), particularly dynamic random-access memory (DRAM). Since the turn of the century, a type of non-volatile floating-gate semiconductor memory known as flash memory has steadily gained share as off-line storage for home computers. Non-volatile semiconductor memory is also used for secondary storage in various advanced electronic devices and specialized computers that are designed for them.

As early as 2006, notebook and desktop computer manufacturers started using flash-based solid-state drives (SSDs) as default configuration options for the secondary storage either in addition to or instead of the more traditional HDD.[35][36][37][38][39]

Magnetic

[edit]Magnetic storage uses different patterns of magnetization on a magnetically coated surface to store information. Magnetic storage is non-volatile. The information is accessed using one or more read/write heads which may contain one or more recording transducers. A read/write head only covers a part of the surface so that the head or medium or both must be moved relative to another in order to access data. In modern computers, magnetic storage will take these forms:

- Magnetic disk;

- Floppy disk, used for off-line storage;

- Hard disk drive, used for secondary storage.

- Magnetic tape, used for tertiary and off-line storage;

- Carousel memory (magnetic rolls).

In early computers, magnetic storage was also used as:

- Microcode storage in transformer read-only storage;

- Primary storage in a form of magnetic memory, or core memory, core rope memory, thin-film memory and/or twistor memory;

- Magnetic-tape was often used for secondary storage;

- Tertiary (e.g. NCR CRAM) or off line storage in the form of magnetic cards.

Magnetic storage does not have a definite limit of rewriting cycles like flash storage and re-writeable optical media, as altering magnetic fields causes no physical wear. Rather, their life span is limited by mechanical parts.[40][41]

Optical

[edit]Optical storage, the typical optical disc, stores information in deformities on the surface of a circular disc and reads this information by illuminating the surface with a laser diode and observing the reflection. Optical disc storage is non-volatile. The deformities may be permanent (read only media), formed once (write once media) or reversible (recordable or read/write media). The following forms are in common use as of 2009[update]:[42]

- CD, CD-ROM, DVD, BD-ROM: Read only storage, used for mass distribution of digital information (music, video, computer programs);

- CD-R, DVD-R, DVD+R, BD-R: Write once storage, used for tertiary and off-line storage;

- CD-RW, DVD-RW, DVD+RW, DVD-RAM, BD-RE: Slow write, fast read storage, used for tertiary and off-line storage;

- Ultra Density Optical or UDO is similar in capacity to BD-R or BD-RE and is slow write, fast read storage used for tertiary and off-line storage.

Magneto-optical disc storage is optical disc storage where the magnetic state on a ferromagnetic surface stores information. The information is read optically and written by combining magnetic and optical methods. Magneto-optical disc storage is non-volatile, sequential access, slow write, fast read storage used for tertiary and off-line storage.

3D optical data storage has also been proposed.

Light induced magnetization melting in magnetic photoconductors has also been proposed for high-speed low-energy consumption magneto-optical storage.[43]

Paper

[edit]Paper data storage, typically in the form of paper tape or punched cards, has long been used to store information for automatic processing, particularly before general-purpose computers existed. Information was recorded by punching holes into the paper or cardboard medium and was read mechanically (or later optically) to determine whether a particular location on the medium was solid or contained a hole. Barcodes make it possible for objects that are sold or transported to have some computer-readable information securely attached.

Relatively small amounts of digital data (compared to other digital data storage) may be backed up on paper as a matrix barcode for very long-term storage, as the longevity of paper typically exceeds even magnetic data storage.[44][45]

Other

[edit]- Vacuum-tube memory:

- A Williams tube used a cathode-ray tube, and a Selectron tube used a large vacuum tube to store information.

- Electro-acoustic memory: Delay-line memory used sound waves in a substance such as mercury to store information.

- Optical tape is a medium for optical storage, generally consisting of a long and narrow strip of plastic, onto which patterns can be written and from which the patterns can be read back.

- Phase-change memory uses different mechanical phases of phase-change material to store information in an X–Y addressable matrix and reads the information by observing the varying electrical resistance of the material.

- Holographic data storage stores information optically inside crystals or photopolymers, for example, in HVDs (Holographic Versatile Discs). Holographic storage can utilize the whole volume of the storage medium, unlike optical disc storage, which is limited to a small number of surface layers.

- Magnetic photoconductors store magnetic information, which can be modified by low-light illumination.[43]

- Molecular memory stores information in polymers that can store electric charge.[46]

- DNA stores digital information in DNA nucleotides.[47][48][49][50]

See also

[edit]- Aperture (computer memory)

- Mass storage

- Memory leak

- Memory protection

- Page address register

- Stable storage

Secondary, tertiary and off-line storage topics

[edit]- Data deduplication

- Data proliferation

- Data storage tag used for capturing research data

- Disk utility

- File system

- Flash memory

- Geoplexing

- Information repository

- Noise-predictive maximum-likelihood detection

- Removable media

- Spindle

- Virtual tape library

- Wait state

- Write buffer

- Write protection

- Cold data

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022.

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Patterson, David A.; Hennessy, John L. (2005). Computer organization and design: The hardware/software interface (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. ISBN 1-55860-604-1. OCLC 56213091.

- ^ D. Tang, Denny; Lee, Yuan-Jen (2010). Magnetic memory: Fundamentals and technology. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1139484497. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ Fletcher, William (1980). An engineering approach to digital design. Prentice-Hall. p. 283. ISBN 0-13-277699-5.

- ^ "4 Ways: Transfer Files from One OneDrive Account to Another without Downloading". MultCloud. 2023. Archived from the original on 16 June 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ "What S.M.A.R.T. hard disk errors actually tell us". Backblaze. 6 October 2016.

- ^ "QPxTool - check the quality". qpxtool.sourceforge.io.

- ^ Storage as defined in Microsoft Computing Dictionary, 4th Ed. (c)1999 or in The Authoritative Dictionary of IEEE Standard Terms, 7th Ed., (c) 2000.

- ^ "Primary storage or storage hardware (shows usage of term "primary storage" meaning "hard disk storage")". searchstorage.techtarget.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "Documentation for /proc/sys/vm/ — The Linux Kernel documentation".

- ^ The Essentials of Computer Organization and Architecture. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7637-3769-6.

- ^ J. S. Vitter (2008). Algorithms and data structures for external memory (PDF). Series on foundations and trends in theoretical computer science. Hanover, MA: now Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60198-106-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2011.

- ^ Pearson, Tony (2010). "Correct use of the term nearline". IBM developer-works, inside system storage. Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ National Communications System (7 August 1996). Federal Standard 1037C – Telecommunications: Glossary of Telecommunication Terms (Technical report). General Services Administration. FS-1037C. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2007. See also article Federal standard 1037C.

- ^ "Disaster Recovery on AWS Cloud". 18 August 2023.

- ^ "On-premises private cloud storage description, characteristics, and options". Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ "ISO/IEC 22123-2:2023(E) - Information technology — Cloud computing — Part 2: Concepts". International Organization for Standardization. September 2023.

- ^ "The Attack Surface Problem". Sans.edu. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Mell, Peter; Timothy Grance (September 2011). The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing (Technical report). National Institute of Standards and Technology: U.S. Department of Commerce. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-145. Special publication 800-145.

- ^ Jones, Margaret (July 2019). "Hybrid Cloud Storage". SearchStorage. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Barrett, Mike (July 2014). "Definition: cloud storage gateway". SearchStorage. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Barrett, Mike (July 2014). "Definition: cloud storage gateway". SearchStorage. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Rouse, Margaret. "What is public cloud?". Definition from Whatis.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ Kolodner, Elliot K.; Tal, Sivan; Kyriazis, Dimosthenis; Naor, Dalit; Allalouf, Miriam; Bonelli, Lucia; Brand, Per; Eckert, Albert; Elmroth, Erik; Gogouvitis, Spyridon V.; Harnik, Danny; Hernandez, Francisco; Jaeger, Michael C.; Bayuh Lakew, Ewnetu; Manuel Lopez, Jose; Lorenz, Mirko; Messina, Alberto; Shulman-Peleg, Alexandra; Talyansky, Roman; Voulodimos, Athanasios; Wolfsthal, Yaron (2011). "A Cloud Environment for Data-intensive Storage Services". 2011 IEEE Third International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science. pp. 357–366. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.302.151. doi:10.1109/CloudCom.2011.55. ISBN 978-1-4673-0090-2. S2CID 96939.

- ^ S. Rhea, C. Wells, P. Eaton, D. Geels, B. Zhao, H. Weatherspoon, and J. Kubiatowicz, Maintenance-Free Global Data Storage. IEEE Internet Computing, Vol 5, No 5, September/October 2001, pp 40–49. [1] Archived 2012-03-29 at the Wayback Machine [2] Archived 2011-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wittig, Andreas; Wittig, Michael (2015). Amazon web services in action. Manning press. pp. 204–206. ISBN 978-1-61729-288-0.

- ^ Taneja, Arun. "How an object store differs from file and block storage". TechTarget.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "What is file level storage versus block level storage?". Stonefly. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012.

- ^ Wittig & Wittig (2015), p. 205.

- ^ Wittig & Wittig (2015), pp. 212–214.

- ^ Wittig & Wittig (2015), p. 212.

- ^ "Super Talent's 2.5" IDE flash hard drive". The tech report. 12 July 2006. p. 13. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "Power consumption – Tom's hardware : Conventional hard drive obsoletism? Samsung's 32 GB flash drive previewed". tomshardware.com. 20 September 2006. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ a b Aleksey Meyev (23 April 2008). "SSD, i-RAM and traditional hard disk drives". X-bit labs. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008.

- ^ Karen Scarfone; Murugiah Souppaya; Matt Sexton (November 2007). "Guide to storage encryption technologies for end user devices" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- ^ "New Samsung notebook replaces hard drive with flash". Extreme tech. 23 May 2006. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "Toshiba tosses hat into notebook flash storage ring". technewsworld.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "Mac Pro – Storage and RAID options for your Mac Pro". Apple. 27 July 2006. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "MacBook Air – The best of iPad meets the best of Mac". Apple. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "MacBook Air replaces the standard notebook hard disk for solid state flash storage". news.inventhelp.com. 15 November 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ "Comparing SSD and HDD endurance in the age of QLC SSDs" (PDF). Micron technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Comparing SSD and HDD - A comprehensive comparison of the storage drives". www.stellarinfo.co.in. 28 February 2025.

- ^ "The DVD FAQ - A comprehensive reference of DVD technologies". Archived from the original on 22 August 2009.

- ^ a b Náfrádi, Bálint (24 November 2016). "Optically switched magnetism in photovoltaic perovskite CH3NH3(Mn:Pb)I3". Nature Communications. 7 13406. arXiv:1611.08205. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713406N. doi:10.1038/ncomms13406. PMC 5123013. PMID 27882917.

- ^ "A paper-based backup solution (not as stupid as it sounds)". 14 August 2012.

- ^ Sterling, Bruce (16 August 2012). "PaperBack paper backup". Wired.

- ^ "New method of self-assembling nanoscale elements could transform data storage industry". sciencedaily.com. 1 March 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ Yong, Ed. "This speck of DNA contains a movie, a computer virus, and an Amazon gift card". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 3 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Researchers store computer operating system and short movie on DNA". phys.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "DNA could store all of the world's data in one room". Science Magazine. 2 March 2017. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Erlich, Yaniv; Zielinski, Dina (2 March 2017). "DNA Fountain enables a robust and efficient storage architecture". Science. 355 (6328): 950–954. Bibcode:2017Sci...355..950E. doi:10.1126/science.aaj2038. PMID 28254941. S2CID 13470340.

Further reading

[edit]- Goda, K.; Kitsuregawa, M. (2012). "The history of storage systems". Proceedings of the IEEE. 100: 1433–1440. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2012.2189787.

- Memory & storage, Computer history museum

Computer data storage

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Functionality

Computer data storage refers to the technology used for the recording (storing) and subsequent retrieval of digital information within computing devices, enabling the retention of data in forms such as electronic signals, magnetic patterns, or optical markings.[5] This process underpins the functionality of computers by allowing information to be preserved beyond immediate processing sessions, facilitating everything from simple data logging to complex computational tasks.[6] The concept of data storage has evolved significantly since its early mechanical forms. In the late 1880s, punched cards emerged as one of the first practical methods for storing and processing data, initially developed by Herman Hollerith for the 1890 U.S. Census to encode demographic information through punched holes that could be read by mechanical tabulating machines.[7] Over the 20th century, this gave way to electronic methods, transitioning from vacuum tube-based systems in the mid-1900s to contemporary solid-state and magnetic technologies that represent data more efficiently and at higher densities.[8] At its core, the storage process involves writing data by encoding information into binary bits—represented as 0s and 1s—onto a physical medium through hardware mechanisms, such as altering magnetic orientations or electrical charges.[9] Retrieval, or reading, reverses this by detecting those bit representations via specialized interfaces, like read/write heads or sensors, and converting them back into usable digital signals for the computer's processor.[10] This write-store-read cycle ensures data integrity and accessibility, forming the foundational operation for all storage systems. In computing, data storage plays a critical role in supporting program execution by holding instructions and operands that the central processing unit (CPU) fetches and processes sequentially.[11] It also enables data processing tasks, such as calculations or transformations, by providing persistent access to intermediate results, and ensures long-term preservation of files, databases, and archives even after power is removed.[12] A key distinction exists between storage and memory: while memory (often primary, like RAM) offers fast but volatile access to data during active computation—losing contents without power—storage provides non-volatile persistence for long-term retention, typically at the cost of slower access speeds.[13] This separation allows computing systems to balance immediate performance needs with durable data safeguarding.[14]Data Organization and Representation

At the most fundamental level, computer data storage represents information using binary digits, or bits, where each bit is either a 0 or a 1, serving as the smallest unit of data.[15] Groups of eight bits form a byte, which is the basic addressable unit in most computer systems and can represent 256 distinct values.[16] This binary foundation allows computers to store and manipulate all types of data, from numbers to text and multimedia, by interpreting bit patterns according to predefined conventions.[17] Characters are encoded into binary using standardized schemes to ensure consistent representation across systems. The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII), a 7-bit encoding that supports 128 characters primarily for English text, maps each character to a unique binary value, such as 01000001 for 'A'.[18] For broader international support, Unicode extends this capability with a 21-bit code space accommodating over 1.1 million characters, encoded in forms like UTF-8 (variable-length, 1-4 bytes per character for backward compatibility with ASCII) or UTF-16 (2-4 bytes using 16-bit units). These encodings preserve textual data integrity during storage and transmission by assigning fixed or variable binary sequences to symbols.[19] Data is organized into higher-level structures to facilitate efficient access and management. At the storage device level, data resides in sectors, the smallest physical read/write units typically 512 bytes or 4 KB in size, grouped into larger blocks for file system allocation.[20] Files represent logical collections of related data, such as documents or programs, stored as sequences of these blocks. File systems provide the organizational framework, mapping logical file structures to physical storage while handling metadata like file names, sizes, and permissions. For example, the File Allocation Table (FAT) system uses a table to track chains of clusters (groups of sectors) for simple, cross-platform compatibility.[21] NTFS, used in Windows, employs a master file table with extensible records for advanced features like security attributes and journaling. Similarly, ext4 in Linux divides the disk into block groups containing inodes (structures holding file metadata and block pointers) and data blocks, enabling extents for contiguous allocation to reduce fragmentation.[22] A key aspect of data organization is the distinction between logical and physical representations, achieved through abstraction layers in operating systems and file systems. Logical organization presents data as a hierarchical structure of files and directories, independent of the underlying hardware, allowing users and applications to interact without concern for physical details like disk geometry or sector layouts.[20] Physical organization, in contrast, deals with how bits are actually placed on media, such as track and cylinder arrangements on hard drives, but these details are hidden by the abstraction to enable portability across devices.[23] This separation ensures that changes to physical storage do not disrupt logical data access. To optimize storage efficiency and reliability, data organization incorporates compression and encoding techniques. Lossless compression methods, such as Huffman coding, assign shorter binary codes to more frequent symbols based on their probabilities, reducing file sizes without data loss; the original algorithm, developed in 1952, constructs optimal prefix codes for this purpose. Lossy compression, common for media like images and audio, discards less perceptible information to achieve higher ratios, as in JPEG standards, but is selective to maintain acceptable quality.[24] Error-correcting codes enhance organizational integrity by adding redundant bits; for instance, Hamming codes detect and correct single-bit errors in blocks using parity checks, as introduced in 1950 for reliable transmission and storage.[25] Redundancy at the organizational level, such as in Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks (RAID), distributes data across multiple drives with parity or mirroring to tolerate failures, treating the array as a single logical unit while providing fault tolerance.[26] Non-volatile storage preserves this organization during power loss, maintaining bit patterns and structures intact.[15]Storage Hierarchy

Primary Storage

Primary storage, also known as main memory or random access memory (RAM), serves as the computer's internal memory directly accessible by the central processing unit (CPU) for holding data and instructions temporarily during active processing and computation.[3] It enables the CPU to read and write data quickly without relying on slower external storage, facilitating efficient execution of programs in the von Neumann architecture, where both instructions and data are stored in the same addressable memory space.[27] The primary types of primary storage are static RAM (SRAM) and dynamic RAM (DRAM). SRAM uses a circuit of four to six transistors per bit to store data stably without periodic refreshing, offering high speed but at a higher cost and lower density, making it suitable for CPU caches.[28] In contrast, DRAM stores each bit in a capacitor that requires periodic refreshing to maintain charge, allowing for greater density and lower cost, which positions it as the dominant choice for main system memory.[29] Historically, primary storage evolved from vacuum tube-based memory in the 1940s, as seen in early computers like the ENIAC, which used thousands of tubes for temporary data retention but suffered from high power consumption and unreliability.[30] The shift to semiconductor memory began in the 1970s with the introduction of DRAM by Intel in 1970, enabling denser and more efficient storage.[31] Modern iterations culminated in DDR5 SDRAM, standardized by JEDEC in July 2020, which supports higher bandwidth and capacities through on-module voltage regulation.[32] Key characteristics of primary storage include access times in the range of 5-10 nanoseconds for typical DRAM implementations, allowing rapid CPU interactions, though capacities are generally limited to several gigabytes in consumer systems to balance cost and performance.[33] The CPU integrates with primary storage via the address bus, which specifies the memory location (unidirectional from CPU to memory), and the data bus, which bidirectionally transfers the actual data bits between the CPU and memory modules.[34] This direct connection positions primary storage as the fastest tier in the overall storage hierarchy, above secondary storage for persistent data.[35]Secondary Storage

Secondary storage refers to non-volatile memory devices that provide high-capacity, long-term data retention for computer systems, typically operating at speeds slower than primary storage but offering persistence even when power is removed. These devices store operating systems, applications, and user files, serving as the primary repository for data that requires infrequent but reliable access. Unlike primary storage, which is directly accessible by the CPU for immediate processing, secondary storage acts as an external medium, often magnetic or solid-state based, to hold semi-permanent or permanent data.[3][36] The most common examples of secondary storage include hard disk drives (HDDs), which use magnetic platters to store data through rotating disks and read/write heads, and solid-state drives (SSDs), which employ flash-based non-volatile memory for faster, more reliable operation without moving parts. HDDs remain prevalent for their cost-effectiveness in bulk storage, while SSDs have gained dominance in performance-critical scenarios due to their superior read/write speeds and durability. Access to secondary storage occurs at the block level, where data is organized into fixed-size blocks managed by storage controllers, enabling efficient input/output (I/O) operations via protocols like SCSI or ATA. To bridge the performance gap between secondary storage and the CPU, caching mechanisms temporarily store frequently accessed blocks in faster primary memory, reducing latency for repeated reads.[37][38][39][40] Historically, secondary storage evolved from the IBM 305 RAMAC system introduced in 1956, the first commercial computer with a random-access magnetic disk drive, which provided 5 MB of capacity on 50 spinning platters and revolutionized data accessibility for business applications. This milestone paved the way for modern developments, such as the adoption of NVMe (Non-Volatile Memory Express) interfaces for SSDs in the 2010s, starting with the specification's release in 2011, which optimized PCIe connections for low-latency, high-throughput access in enterprise environments. Today, secondary storage dominates data centers, where HDDs and SSDs handle vast datasets for cloud services and analytics; SSD shipments are projected to grow at a compound annual rate of 8.2% from 2024 to 2029, fueled by surging AI infrastructure demands that require rapid data retrieval and expanded capacity.[41][42][43]Tertiary Storage

Tertiary storage encompasses high-capacity archival systems designed for infrequently accessed data, such as backups and long-term retention, typically implemented as libraries using removable media like magnetic tapes or optical discs. These systems extend the storage hierarchy beyond primary and secondary levels by providing enormous capacities at low cost, often in the form of tape silos or automated libraries that house thousands of media cartridges. Unlike secondary storage, which emphasizes a balance of speed and capacity for active data, tertiary storage focuses on massive scale for cold data that is rarely retrieved, making it suitable for petabyte- to exabyte-scale repositories.[44][45][46] A key example of tertiary storage is magnetic tape technology, particularly the Linear Tape-Open (LTO) standard, which dominates enterprise archival applications. LTO-9 cartridges, released in 2021, provide 18 TB of native capacity, expandable to 45 TB with 2.5:1 compression, enabling efficient storage of large datasets on a single medium. As of November 2025, the LTO-10 specification provides 40 TB of native capacity per cartridge, expandable to 100 TB with 2.5:1 compression, supporting the growing demands of data-intensive environments like AI training archives and media preservation.[47][48] These tape systems are housed in silos that allow for bulk storage, with ongoing roadmap developments projecting even higher densities in future generations. Access to data in tertiary storage is primarily sequential, requiring media mounting via automated library mechanisms for retrieval, which introduces latency but suits infrequent operations. In enterprise settings, these systems are employed for compliance and regulatory data retention, where legal requirements mandate long-term preservation of records such as financial audits or healthcare logs without frequent access. Reliability in tertiary storage is enhanced by low bit error rates inherent to tape media, providing durable archiving options.[44][49][50] The chief advantage of tertiary storage lies in its exceptional cost-effectiveness per gigabyte, with LTO tape media priced at approximately $0.003 to $0.03 per GB for offline or cold storage, significantly undercutting disk-based solutions for large-scale retention. This economic model supports indefinite data holding at minimal ongoing expense, ideal for organizations managing exponential data growth while adhering to retention policies. In contrast to off-line storage, tertiary systems remain semi-online through library integration, facilitating managed access without physical disconnection.[51][52][53] Hierarchical storage management (HSM) software is integral to tertiary storage, automating the migration of inactive data from higher tiers to archival media based on predefined policies for access frequency and age. HSM optimizes resource utilization by transparently handling tiering, ensuring that cold data resides in low-cost tertiary storage while hot data stays on faster media, thereby reducing overall storage expenses and improving system performance. This policy-driven approach enables seamless data lifecycle management in distributed environments.[54][55]Off-line Storage

Off-line storage refers to data storage on media or devices that are physically disconnected from a computer or network, requiring manual intervention to access or transfer data. This approach ensures that the storage medium is not under the direct control of the system's processing unit, making it ideal for secure transport and long-term preservation.[56][57] Common examples include optical discs such as CDs and DVDs, which store data via laser-etched pits for read-only distribution, and removable flash-based devices like USB drives and external hard disk drives, which enable portable data transfer between systems. These media are frequently used for creating backups, distributing software or files, and archiving infrequently accessed information in environments where immediate availability is not required.[56][58] A primary security advantage of off-line storage is its air-gapped nature, which physically isolates data from network-connected threats, preventing unauthorized access, ransomware encryption, or manipulation by cybercriminals. This isolation is particularly valuable for protecting sensitive information, as the media cannot be reached through digital intrusions without physical handling.[59][60] Historically, off-line storage evolved from early magnetic tapes and punch cards in the mid-20th century to the introduction of floppy disks in the 1970s, which provided compact, removable media for personal computing. By the 1980s and 1990s, advancements led to higher-capacity options like ZIP drives and CDs, transitioning in the 2000s to modern encrypted USB drives and solid-state external disks that support secure, high-speed transfers.[61][62] Off-line storage remains essential for disaster recovery, allowing organizations to maintain recoverable copies of critical data in physically separate locations to mitigate risks from hardware failures, natural disasters, or site-wide outages. By 2025, hybrid solutions combining off-line media with cloud-based verification are emerging for edge cases, such as initial seeding of large datasets followed by periodic air-gapped checks to enhance resilience without full reliance on online access.[63][64][65]Characteristics of Storage

Volatility

In computer data storage, volatility refers to the property of a storage medium to retain or lose data in the absence of electrical power. Volatile storage loses all stored information when power is removed, as it relies on continuous energy to maintain data states, whereas non-volatile storage preserves data indefinitely without power supply. For example, dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), a common form of volatile storage, is used in system RAM, while hard disk drives (HDDs) and solid-state drives (SSDs) exemplify non-volatile storage for persistent data retention.[66][67] The physical basis for volatility in DRAM stems from its use of capacitors to store bits as electrical charges; without power, these capacitors discharge through leakage currents via the access transistor, leading to data loss within milliseconds to seconds depending on cell design and environmental factors. In contrast, non-volatile flash memory in SSDs employs a floating-gate transistor structure where electrons are trapped in an isolated oxide layer, enabling charge retention for years even without power due to the high energy barrier preventing leakage. This fundamental difference arises from the storage mechanisms: transient charge in DRAM versus stable electron tunneling in flash.[68][69][70][71] Volatility has significant implications for system design: volatile storage is ideal for temporary data processing during active computation, such as holding running programs and variables in main memory, due to its low latency for read/write operations. Non-volatile storage, however, ensures data persistence across power cycles, making it suitable for archiving operating systems, applications, and user files. In the storage hierarchy, all primary storage technologies, like RAM, are inherently volatile to support rapid access for the CPU, while secondary and tertiary storage, such as magnetic tapes or optical discs, are non-volatile to provide durable, long-term data preservation.[72][73] A key trade-off of volatility is that it enables higher performance through simpler, faster circuitry without the overhead of persistence mechanisms, but it demands regular backups to non-volatile media to mitigate the risk of total data loss upon power failure or system shutdown. This balance influences overall system reliability, as volatile components accelerate processing but require complementary non-volatile layers for fault tolerance.[74][75]Mutability

Mutability in computer data storage refers to the capability of a storage medium to allow data to be modified, overwritten, or erased after it has been initially written. This property contrasts with immutability, where data cannot be altered once stored. Storage media are broadly categorized into read/write (mutable) types, which permit repeated modifications, and write once, read many (WORM) types, which allow a single write operation followed by unlimited reads but no further changes.[76][77] Representative examples illustrate these categories. Read-only memory (ROM) exemplifies immutable storage, as its contents are fixed during manufacturing and cannot be altered by the user, ensuring reliable execution of firmware or boot code.[78] In contrast, hard disk drives (HDDs) represent fully mutable media, enabling frequent read and write operations to magnetic platters for dynamic data management in operating systems and applications.[79] Optical discs, such as CD-Rs, offer partial immutability: they function as WORM media after data is burned into the disc using a laser, preventing subsequent overwrites while allowing repeated reads.[80] While mutability supports flexible data handling, it introduces limitations, particularly in solid-state storage like NAND flash memory. Triple-level cell (TLC) NAND, common in consumer SSDs, endures approximately 1,000 to 3,000 program/erase (P/E) cycles per cell before reliability degrades due to physical wear from repeated writes.[81] Mutability facilitates dynamic data environments but increases risks of corruption from errors during modification; by 2025, mutable storage optimized for AI workloads, such as managed-retention memory, is emerging to balance endurance and performance for inference tasks.[82] Non-volatile media, which retain data without power, often incorporate mutability to enable such updates, distinguishing them from volatile counterparts.[83] Applications of mutability vary by use case. Immutable WORM storage is ideal for long-term archives, where data integrity must be preserved against alterations, as seen in archival systems like Deep Store.[83] Conversely, mutable storage underpins databases, allowing real-time updates to structured data in systems like Bigtable, which supports scalable modifications across distributed environments.[84]Accessibility

Accessibility in computer data storage refers to the ease and speed of locating and retrieving data from a storage medium, determining how efficiently systems can interact with stored information. This characteristic is fundamental to overall system performance, as it directly affects response times for data operations in computing environments. Storage devices primarily employ two access methods: random access and sequential access. Random access enables direct retrieval of data from any specified location without needing to process intervening data, allowing near-constant time access regardless of position; this is exemplified by solid-state drives (SSDs), where electronic addressing facilitates rapid location of blocks.[85] In contrast, sequential access involves reading or writing data in a linear, ordered fashion from start to end, which is characteristic of magnetic tapes and suits bulk sequential operations like backups but incurs high penalties for non-linear retrievals./Electronic%20Records/Electronic%20Records%20Management%20Guidelines/ermDM.pdf) Metrics for evaluating accessibility focus on latency and throughput. Latency, often quantified as seek time, measures the duration to position the access mechanism—such as a disk head or electronic pointer—at the target data, typically ranging from microseconds in primary storage to tens of milliseconds in secondary devices. Throughput, or transfer rate, assesses the volume of data moved per unit time after access is initiated, influencing sustained read/write efficiency.[86] Several factors modulate accessibility, including interface standards and architectural enhancements. Standards like Serial ATA (SATA) provide reliable connectivity for secondary storage but introduce overhead, resulting in higher latencies compared to Peripheral Component Interconnect Express (PCIe), which supports direct, high-speed paths and can achieve access latencies as low as 6.8 microseconds for PCIe-based SSDs—up to eight times faster than SATA equivalents. Caching layers further enhance accessibility by temporarily storing hot data in faster tiers, such as DRAM buffers within SSD controllers, thereby masking underlying medium latencies and improving hit rates for repeated accesses.[87][88] Across the storage hierarchy, accessibility varies markedly: primary storage like RAM delivers sub-microsecond access times, enabling near-instantaneous retrieval for active computations, whereas tertiary storage, such as robotic tape libraries, often demands minutes for operations involving cartridge mounting and seeking due to mechanical delays.[89][90] Historically, accessibility evolved from the magnetic drum memories of the 1950s, which provided random access to secondary storage with average seek times around 7.5 milliseconds, marking an advance over purely sequential media. Contemporary NVMe protocols over PCIe have propelled this forward, delivering sub-millisecond random read latencies on modern SSDs and supporting high input/output operations per second for data-intensive applications.[91]Addressability

Addressability in computer data storage refers to the capability of a storage system to uniquely identify and locate specific units of data through assigned addresses, enabling precise retrieval and manipulation. In primary storage such as random-access memory (RAM), systems are typically byte-addressable, meaning each byte—a sequence of 8 bits—can be directly accessed using a unique address, which has been the standard for virtually all computers since the 1970s.[92] This fine-grained access supports efficient operations at the byte level, though individual bits within a byte are not independently addressable in standard implementations. In contrast, secondary storage devices like hard disk drives (HDDs) and solid-state drives (SSDs) are block-addressable, where data is organized and accessed in larger fixed-size units known as blocks or sectors, typically 512 bytes or 4 kilobytes in size, to optimize mechanical or electronic constraints.[93] Key addressing mechanisms in storage systems include logical block addressing (LBA) for disks and virtual memory addressing for RAM. LBA abstracts the physical geometry of a disk by assigning sequential numbers to blocks starting from 0, allowing the operating system to treat the drive as a linear array of addressable units without concern for underlying cylinders, heads, or sectors—a shift from older cylinder-head-sector (CHS) methods to support larger capacities.[94] In virtual memory systems, addresses generated by programs are virtual and translated via hardware mechanisms like page tables into physical addresses in RAM, providing each process with the illusion of a dedicated, contiguous address space while managing fragmentation and sharing.[95] These approaches facilitate efficient indexing and mapping, with LBA playing a role in file systems by enabling block-level allocation for files.[96] The granularity of addressability varies across storage types, reflecting hardware design trade-offs between precision and efficiency. In RAM, the addressing unit is a byte, allowing operations down to this scale for most data types. In secondary storage, it coarsens to the block level to align with device read/write cycles, though higher-level abstractions like file systems address data at the file or record granularity for organized access. Modern disk interfaces employ 48-bit LBA to accommodate petabyte-scale drives up to 128 petabytes (or approximately 256 petabytes with 4 KB sectors), an advancement introduced in ATA-6 to extend beyond the 28-bit limit of 128 gigabytes.[97][98] Legacy systems faced address space exhaustion due to limited bit widths, such as 32-bit addressing capping virtual memory at 4 gigabytes, which became insufficient for growing applications and led to the widespread adoption of 64-bit architectures for vastly expanded spaces. Similarly, pre-48-bit LBA in disks restricted capacities, prompting transitions to extended addressing to prevent obsolescence as storage densities increased.[99][100]Capacity

Capacity in computer data storage refers to the total amount of data that a storage device or system can hold, measured in fundamental units that scale to represent increasingly large volumes. The basic unit is the bit, representing a single binary digit (0 or 1), while a byte consists of eight bits and serves as the standard unit for data size. Larger quantities use prefixes: kilobyte (KB) as 10^3 bytes in decimal notation commonly used by manufacturers, or 2^10 (1,024) bytes in binary notation preferred by operating systems; this extends to megabyte (MB, 10^6 or 2^20 bytes), gigabyte (GB, 10^9 or 2^30 bytes), terabyte (TB, 10^12 or 2^40 bytes), petabyte (PB, 10^15 or 2^50 bytes), exabyte (EB, 10^18 or 2^60 bytes), zettabyte (ZB, 10^21 or 2^70 bytes).[101][102] This distinction arises because storage vendors employ decimal prefixes for marketing capacities, leading to discrepancies where a labeled 1 TB drive provides approximately 931 GiB (2^30 bytes) when viewed in binary terms by software.[101] Storage capacity is typically specified as raw capacity, which denotes the total physical space available on the media before any formatting or overhead, versus formatted capacity, which subtracts space reserved for filesystem structures, error correction, and metadata, often reducing usable space by 10-20%.[103] For example, a drive with 1 TB raw capacity might yield around 900-950 GB of formatted capacity depending on the filesystem.[104] In the storage hierarchy, capacity generally increases from primary storage (smallest, e.g., kilobytes to gigabytes in RAM) to tertiary and off-line storage (largest, up to petabytes or more).[103] Key factors influencing capacity include data density, measured as bits stored per unit area (areal density) or volume, which has historically followed an analog to Moore's Law with areal density roughly doubling every two years in hard disk drives.[105] Innovations like helium-filled HDDs enhance this by reducing internal turbulence and friction, allowing more platters and up to 50% higher capacity compared to air-filled equivalents.[106] For solid-state drives, capacity scales through advancements in 3D NAND flash, where stacking more layers vertically increases volumetric density; by 2023, this enabled enterprise SSDs exceeding 30 TB via 200+ layer architectures.[107] Trends in storage capacity reflect exponential growth driven by these density improvements. Global data creation is projected to reach 175 zettabytes by 2025, fueled by IoT, cloud computing, and AI applications.[108] In 2023, hard disk drives achieved capacities over 30 TB per unit through technologies like heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR) and shingled magnetic recording (SMR), while SSDs continued scaling via multi-layer 3D NAND to meet demand for high-capacity, non-volatile storage.[109]Performance

Performance in computer data storage refers to the efficiency with which data can be read from or written to a storage device, primarily measured through key metrics such as input/output operations per second (IOPS), bandwidth, and latency. IOPS quantifies the number of read or write operations a storage system can handle in one second, particularly useful for random access workloads where small data blocks are frequently accessed. Bandwidth, expressed in megabytes per second (MB/s), indicates the rate of data transfer for larger sequential operations, such as copying files or streaming media. Latency measures the time delay between issuing a request and receiving the response, typically in microseconds (μs) for solid-state drives (SSDs) and milliseconds (ms) for hard disk drives (HDDs), directly impacting responsiveness in time-sensitive applications.[110][111] These metrics vary significantly between storage technologies, with SSDs outperforming HDDs due to the absence of mechanical components. For instance, modern NVMe SSDs using PCIe 5.0 interfaces can achieve over 2 million random 4K IOPS for reads and writes, while high-capacity enterprise HDDs are limited to around 100-1,000 random IOPS, constrained by mechanical seek times of 5-10 ms. Sequential bandwidth for PCIe 5.0 SSDs reaches up to 14,900 MB/s for reads, compared to 250-300 MB/s for HDDs. SSD latency averages 100 μs for random reads, enabling near-instantaneous access that aligns with random accessibility patterns in computing tasks.[112][113] Benchmarks like CrystalDiskMark evaluate these metrics by simulating real-world workloads, distinguishing between sequential and random operations. Sequential benchmarks test large block transfers (e.g., 1 MB or larger), where SSDs excel in throughput due to parallel NAND flash channels, often saturating interface limits like PCIe 5.0's theoretical ~15 GB/s per direction for x4 lanes. Random benchmarks, using 4K blocks, highlight IOPS and latency differences; SSDs maintain high performance across queue depths, while HDDs suffer from head movement delays, making random writes particularly slow at ~100 IOPS. Tools such as CrystalDiskMark provide standardized results, with SSDs showing 10-100x improvements over HDDs in mixed workloads.[114][115] Performance is influenced by hardware factors including controller design, which manages data mapping and error correction to maximize parallelism, and interface standards. The PCIe 5.0 specification, introduced in 2019 and widely adopted by 2025, doubles bandwidth over PCIe 4.0 to approximately 64 GB/s aggregate for x4 configurations, enabling SSDs to handle AI and high-performance computing demands. Advanced controllers in SSDs incorporate techniques like wear leveling to sustain peak IOPS over time.[116][117] Optimizations further enhance storage performance through software and hardware mechanisms. Caching stores frequently accessed data in faster memory tiers, such as DRAM or host RAM, reducing effective latency by avoiding repeated disk accesses. Prefetching anticipates data needs by loading subsequent blocks into cache during sequential reads, boosting throughput in predictable workloads like video editing. In modern systems, AI-driven predictive algorithms analyze access patterns to intelligently prefetch or cache data, improving IOPS by up to 50% in dynamic environments such as cloud databases. These techniques collectively mitigate bottlenecks, ensuring storage keeps pace with processor speeds.[118][119][120]| Metric | SSD (NVMe PCIe 5.0, 2025) | HDD (Enterprise, 2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Random 4K IOPS | Up to 2.6M (read/write) | 100-1,000 |

| Sequential Bandwidth (MB/s) | Up to 14,900 (read) | 250-300 |

| Latency (random read) | ~100 μs | 5-10 ms |