Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Indirect fire

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

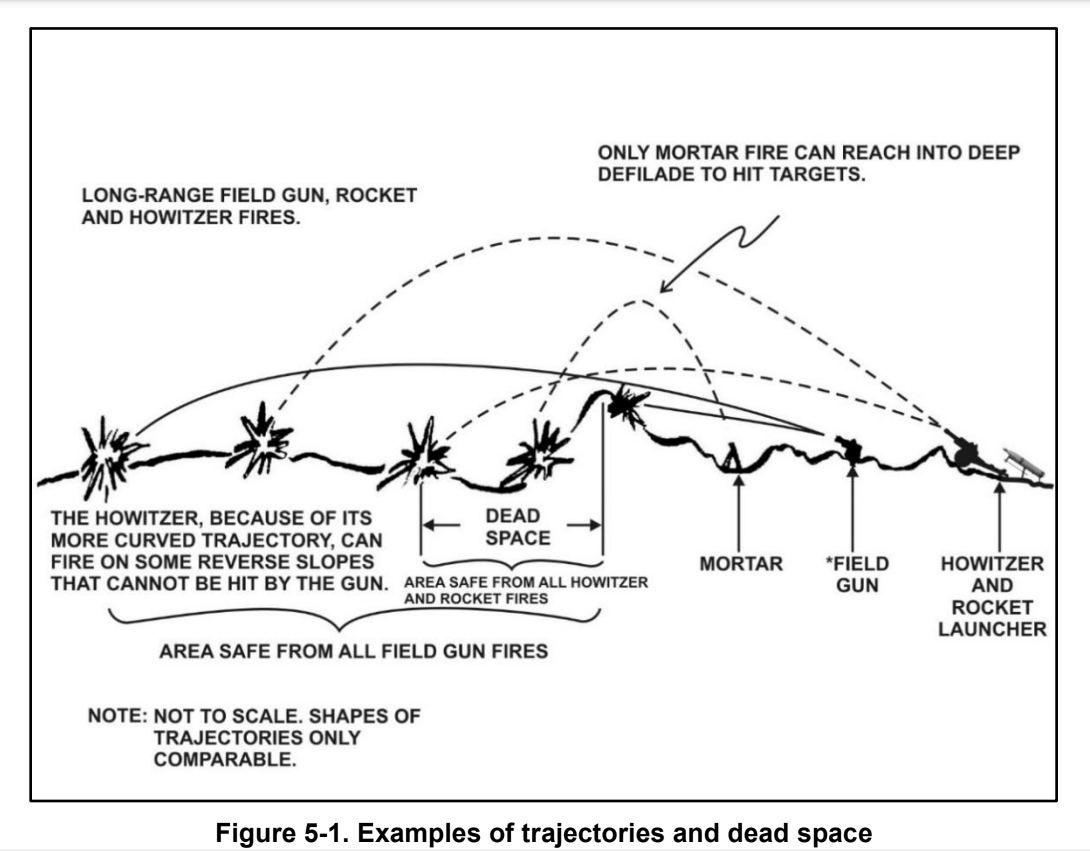

Indirect fire is aiming and firing a projectile without relying on a direct line of sight between the gun and its target, as in the case of direct fire. Aiming is performed by calculating azimuth and inclination, and may include correcting aim by observing the fall of shot and calculating new angles.

Description

[edit]Indirect fire is most commonly used by field artillery and mortars (although field artillery was originally and until after World War I a direct fire weapon, hence the bullet-shields fitted to the carriages of guns such as the famous M1897 75 mm). It is also used with missiles, howitzers, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, naval guns against shore targets, sometimes with machine guns, and has been used with tank and anti-tank guns and by anti-aircraft guns against surface targets.

There are two dimensions in aiming a weapon:

- In the horizontal plane (azimuth); and

- In the vertical plane (elevation), which is governed by the distance (range) to the target and the energy of the propelling charge.

The projectile trajectory is affected by atmospheric conditions, the velocity of the projectile, the difference in altitude between the firer and the target, and other factors. Direct fire sights may include mechanisms to compensate for some of these. Handguns and rifles, machine guns, anti-tank guns, tank main guns, many types of unguided rockets, and guns mounted in aircraft are examples of weapons primarily designed for direct fire.

NATO defines indirect fire as "Fire delivered at a target which cannot be seen by the aimer."[1] The implication is that azimuth and/or elevation 'aiming' is done using instrumental methods. Hence indirect fire means applying 'firing data' to azimuth and elevation sights and laying these sights. Longer range uses a higher trajectory, and in theory maximum range is achieved with an elevation angle of 45 degrees.[2][3][4]

It is reasonable to assume that original purpose of indirect fire was to enable fire from a 'covered position', one where gunners can not be seen and engaged by their enemies (that and as the range of artillery lengthened, it was impossible to see the target past all the intervening terrain). The concealment aspect remains important, but from World War I equally important was the capability to concentrate the fire of many artillery batteries at the same target or set of targets. This became increasingly important as the range of artillery increased, allowing each battery to have an ever-greater area of influence, but required command and control arrangements to enable concentration of fire. The physical laws of ballistics means that guns firing larger and heavier projectile can send them farther than smaller-calibre guns firing lighter shells. By the end of the 20th century, the typical maximum range for the most common guns was about 24 to 30 km, up from about 8 km in World War I.

During World War I, covered positions moved farther back and indirect fire evolved to allow any point within range to be attacked, firepower mobility, without moving the firers. If the target cannot be seen from the gun position, there has to be a means of identifying targets and correcting aim according to fall of shot. The position of some targets may be identified by a headquarters from various sources of information (spotters): observers on the ground, in aircraft, or in observation balloons. The development of electrical communication immensely simplified reporting, and enabled many widely dispersed firers to concentrate their fire on one target.

The trajectory of the projectile could not be altered once fired, until the introduction of smart munitions.

History

[edit]Indirect arrow fire by archers was commonly used by ancient armies. It was used during both battles and sieges.[5]

For several centuries Coehorn mortars were fired indirectly because their fixed elevation meant range was determined by the amount of propelling powder. It is also reasonable conjecture that if these mortars were used from inside fortifications their targets may have been invisible to them and therefore met the definition of indirect fire.[original research?]

It could also be argued[according to whom?] that Niccolò Tartaglia's invention of the gunner's quadrant (see clinometer) in the 16th century introduced indirect fire guns because it enabled gunlaying by instrument instead of line of sight.[6] This instrument was basically a carpenter's set square with a graduated arc and plumb-bob placed in the muzzle to measure an elevation. There are suggestions,[7] based on an account in Livre de Canonerie published in 1561 and reproduced in Revue d'Artillerie of March 1908, that indirect fire was used by the Burgundians in the 16th century. The Russians seem to have used something similar at Paltzig in 1759 where they fired over trees, and their instructions of the time indicate this was a normal practice.[8] These methods probably involved an aiming point positioned in line with the target.[citation needed] The earliest example of indirect fire adjusted by an observer seems to be during the defence of Hougoumont in the Battle of Waterloo where a battery of the Royal Horse Artillery fired an indirect Shrapnel barrage against advancing French troops using corrections given by the commander of an adjacent battery with a direct line of sight.[9]

Modern indirect fire dates from the late 19th century. In 1882 a Russian, Lt Col K. G. Guk, published Field Artillery Fire from Covered Positions that described a better method of indirect laying (instead of aiming points in line with the target). In essence, this was the geometry of using angles to aiming points that could be in any direction relative to the target. The problem was the lack of an azimuth instrument to enable it; clinometers for elevation already existed. The Germans solved this problem by inventing the lining-plane in about 1890. This was a gun-mounted rotatable open sight, mounted in alignment with the bore, and able to measure large angles from it. Similar designs, usually able to measure angles in a full circle, were widely adopted over the following decade. By the early 1900s the open sight was sometimes replaced by a telescope and the term goniometer had replaced "lining-plane" in English.

The first incontrovertible, documented use of indirect fire in war using Guk's methods, albeit without lining-plane sights, was on 26 October 1899 by British gunners during the Second Boer War.[10] Although both sides demonstrated early on in the conflict that they could use the technique effectively, in many subsequent battles, British commanders nonetheless ordered artillery to be "less timid" and to move forward to address troops' concerns about their guns abandoning them.[10] The British used improvised gun arcs with howitzers;[7] the sighting arrangements used by the Boers with their German and French guns is unclear.

The early goniometric devices suffered from the problem that the layer (gun aimer) had to move around to look through the sight. This was very unsatisfactory if the aiming point was not to the front, particularly on larger guns. The solution was a periscopic panoramic sight, with the eyepiece to the rear and the rotatable top of the sight above the height of the layer's head. The German Goertz 1906 design was selected by both the British and the Russians. The British adopted the name "Dial Sight" for this instrument; the US used "Panoramic Telescope"; the Russia used "Goertz panorama".

Elevations were measured by a clinometer, a device using a spirit level to measure a vertical angle from the horizontal plane. These could be separate instruments placed on a surface parallel to the axis of the bore or physically integrated into some form of sight mount. Some guns had clinometers graduated in distances instead of angles. Clinometers had several other names including "gunner's level", "range scale", "elevation drum" and "gunner’s quadrant" and several different configurations. Those graduated in ranges were specific to a type of gun.

These arrangements lasted for most of the 20th century until robust, reliable and cost-effectively accurate gyroscopes provided a means of pointing gun or launcher in any required azimuth and elevation, thereby enabling indirect fire without using external aiming points. These devices use gyros in all three axes to determine current elevation, azimuth and trunnion tilt.

Related issues

[edit]

Before a gun or launcher can be aimed, it must be oriented towards a known azimuth, or at least towards a target area. Initially, the angle between the aiming point and target area is deduced, or estimated, and set on the azimuth sight. Each gun is then laid on the aiming point, with this angle in order to keep them aimed roughly parallel to each other. However, for artillery another instrument, called either a director (United Kingdom) or aiming circle (United States), became widespread and eventually the primary method of orienting guns in most if not all armies. After being oriented and pointed in the required direction a gun recorded angles to one or more aiming points. Such early directors were the progenitors of the later general class of directors.

Indirect fire needs a command and control arrangement to allot guns to targets and direct their fire. The latter may involve ground or air observers or technical devices and systems. Observers report where shots fall so that aim may be corrected. In the First World War an important task for aircraft — both heavier-than-air or balloons — was artillery spotting. In naval use several ships may be shooting at the same target, making identifying the fall of shot from a particular ship difficult; different-coloured dyes for each ship were often used to help with spotting.[11]

Fire may be "adjusted" or "predicted". Adjusting (originally "ranging") means some form of observation is used to correct the fall of shot onto the target; this may be required for several possible reasons:

- geospatial relationship between gun and target is not accurately known;

- good quality data for prevailing conditions is unavailable; or

- the target is moving or expected to move.

Predicted fire, originally called "map shooting", was introduced in World War I. It means that firing data is calculated to include corrections for the current prevailing conditions. It requires the target location to be precisely known relative to the gun location.

Adjusted and predicted fire are not mutually exclusive, the former may use predicted data and the latter may need adjusting in some circumstances.

There are two approaches to the azimuth that orients the guns of a battery for indirect fire. Originally "zero", meaning 6400 mils, 360 degrees or their equivalent, was set at whatever the direction the oriented gun was pointed. Firing data was a deflection or switch from this zero.

The other method was to set the sight at the actual grid bearing in which the gun was oriented, and firing data was the actual bearing to the target. The latter reduces sources of mistakes and made it easier to check that the guns were correctly laid. By the late 1950s, most armies had adopted the bearing method, the notable exception being the United States.

See also

[edit]- Cannon-launched guided projectile – Precision-guided artillery munition

- Gun laying – Process of aiming an artillery piece or turret

- Prism paralleloscope

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ AAP-6 NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions

- ^ John Matsumura (2000). Lightning Over Water: Sharpening America's Light Forces for Rapid-Reaction Missions. Rand Corporation. p. 196. ISBN 0-8330-2845-6.

- ^ Michael Goodspeed (2002). When Reason Fails: Portraits of Armies at War: America, Britain, Israel and the Future. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 24. ISBN 0-275-97378-6.

- ^ Jeff Kinard (2007). Artillery: An Illustrated History of its Impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-85109-556-8.

- ^ Gabriel, Richard A. (2007). The Ancient World. Greenwood Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-313-33348-4.

- ^ Artillery: Its Origin, Heyday and Decline, Brigadier O. F. G. Hogg, 1970, C. Hurst and Company

- ^ a b The History of the Royal Artillery from the Indian Mutiny to the Great War, Vol II, 1899–1914, Major General Sir John Headlam, 1934

- ^ "Red God of War" Soviet Artillery and Rocket Forces, Chris Bellamy, 1986

- ^ Against All Odds!: Dramatic Last Stand Actions. Perret, Brian. Cassell 2000. ISBN 978-0-304-35456-6: discussed during the account of the Hougoumont action.

- ^ a b Frank W. Sweet (2000). The Evolution of Indirect Fire. Backintyme. pp. 28–33. ISBN 0-939479-20-6.

- ^ DiGiulian, Tony (2 March 2021). "Definitions and Information about Naval Guns - Ammunition Definitions - Splash Colors". NavWeaps.

References

[edit]- Chris Bellamy (1986). Red God of War" Soviet Artillery and Rocket Forces. Brassey's. ISBN 0-08-031200-4.