Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Faust, Part One

View on WikipediaThis article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (March 2010) |

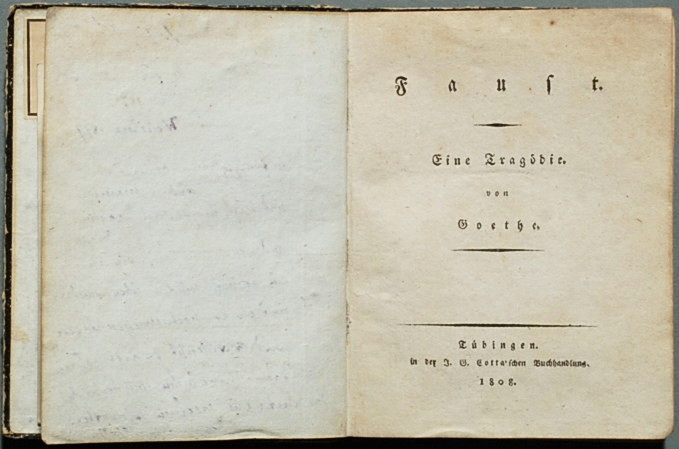

Faust: A Tragedy (German: Faust. Eine Tragödie, pronounced [faʊ̯st ˈaɪ̯nə tʁaˈɡøːdi̯ə] ⓘ, or Faust. Der Tragödie erster Teil [Faust. The tragedy's first part]) is the first part of the tragic play Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and is considered by many as the greatest work of German literature.[1] It was first published in 1808.

Key Information

Synopsis

[edit]The first part of Faust is not divided into acts, but is structured as a sequence of scenes in a variety of settings. After a dedicatory poem and a prelude in the theatre, the actual plot begins with a prologue in Heaven, where the Lord bets Mephistopheles, an agent of the Devil, that Mephistopheles cannot lead astray the Lord's favourite striving scholar, Dr. Faust. We then see Faust in his study, who, disappointed by the knowledge and results obtainable by science's natural means, attempts and fails to gain knowledge of nature and the universe by magical means. Dejected in this failure, Faust contemplates suicide, but is held back by the sounds of the beginning Easter celebrations. He joins his assistant Wagner for an Easter walk in the countryside, among the celebrating people, and is followed home by a poodle. Back in the study, the poodle transforms itself into Mephistopheles, who offers Faust a contract: he will do Faust's bidding on earth, and Faust will do the same for him in Hell (if, as Faust adds in an important side clause, Mephistopheles can get him to be satisfied and to want a moment to last forever). Faust signs in blood, and Mephistopheles first takes him to Auerbach's tavern in Leipzig, where the devil plays tricks on some drunken revellers. Having then been transformed into a young man by a witch, Faust encounters Margaret (Gretchen) and she excites his desires. Through a scheme involving jewellery and Gretchen's neighbour Marthe, Mephistopheles brings about Faust's and Gretchen's liaison.

After a period of separation, Faust seduces Gretchen, who accidentally kills her mother with a sleeping potion given to her by Faust. Gretchen discovers that she is pregnant, and her torment is further increased when Faust and Mephistopheles kill her enraged brother in a sword fight. Mephistopheles seeks to distract Faust by taking him to a Witches' Sabbath on Walpurgis Night, but Faust insists on rescuing Gretchen from the execution to which she was sentenced after drowning her newborn child while in a state of madness. In the dungeon, Faust vainly tries to persuade Gretchen to follow him to freedom. At the end of the drama, as Faust and Mephistopheles flee the dungeon, a voice from heaven announces Gretchen's salvation.

Prologues

[edit]Prologue in the Theatre

In the first prologue, three people (the theatre director, the poet and an actor) discuss the purpose of the theatre. The director approaches the theatre from a financial perspective, and is looking to make an income by pleasing the crowd; the actor seeks his own glory through fame as an actor; and the poet aspires to create a work of art with meaningful content. Many productions use the same actors later in the play to draw connections between characters: the director reappears as God, the actor as Mephistopheles, and the poet as Faust.[2]

Prologue in Heaven: The Wager

The play begins with the Prologue in Heaven. In an allusion to the story of Job, Mephistopheles wagers with God for the soul of Faust.

God has decided to "soon lead Faust to clarity", who previously only "served [Him] confusedly." However, to test Faust, he allows Mephistopheles to attempt to lead him astray. God declares that "man still must err, while he doth strive". It is shown that the outcome of the bet is certain, for "a good man, in his darkest impulses, remains aware of the right path", and Mephistopheles is permitted to lead Faust astray only so that he may learn from his misdeeds.

Faust's tragedy

[edit]Night

The play proper opens with a monologue by Faust, sitting in his study, contemplating all that he has studied throughout his life. Despite his wide studies, he is dissatisfied with his understanding of the workings of the world, and has determined only that he knows "nothing" after all. Science having failed him, Faust seeks knowledge in Nostradamus, in the "sign of the Macrocosmos", and from an Earth-spirit, still without achieving satisfaction.

As Faust reflects on the lessons of the Earth-spirit, he is interrupted by his famulus, Wagner. Wagner symbolizes the vain scientific type who understands only book-learning, and represents the educated bourgeoisie. His approach to learning is a bright, cold quest, in contrast to Faust, who is led by emotional longing to seek divine knowledge.

Dejected, Faust spies a phial of poison and contemplates suicide. However he is halted by the sound of church bells announcing Easter, which remind him not of Christian duty but of his happier childhood days.

Outside the town gate

Faust and Wagner take a walk into the town, where people are celebrating Easter. They hail Faust as he passes them because Faust's father, an alchemist himself, cured the plague. Faust is in a black mood. As they walk among the promenading villagers, Faust reveals to Wagner his inner conflict. Faust and Wagner see a poodle, who they do not know is Mephistopheles in disguise, which follows them into the town.

Study

Faust returns to his rooms, and the dog follows him. Faust translates the Gospel of John, which presents difficulties, as Faust cannot determine the sense of the first sentence (specifically, the word Logos (Ancient Greek: Λὀγος) – "In the beginning was the Logos, and the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God" – currently translated as The Word). Eventually, he settles upon translating it with a meaning Logos does not have, writing "In the beginning was the deed".

The words of the Bible agitate the dog, which shows itself as a monster. When Faust attempts to repel it with sorcery, the dog transforms into Mephistopheles, in the disguise of a travelling scholar. After being confronted by Faust as to his identity, Mephistopheles proposes to show Faust the pleasures of life. At first Faust refuses, but the devil draws him into a wager, saying that he will show Faust things he has never seen. They sign a pact agreeing that if Mephistopheles can give Faust a moment in which he no longer wishes to strive, but begs for that moment to continue, he can have Faust's soul:

Faust. Werd ich zum Augenblicke sagen: |

Faust. If the swift moment I entreat: |

Auerbach's Cellar in Leipzig

In this, and the rest of the drama, Mephistopheles leads Faust through the "small" and "great" worlds. Specifically, the "small world" is the topic of Faust I, while the "great world", escaping also the limitations of time, is reserved for Faust II.

These scenes confirm what was clear to Faust in his overestimation of his strength: he cannot lose the bet, because he will never be satisfied, and thus will never experience the "great moment" Mephistopheles has promised him. Mephistopheles appears unable to keep the pact, since he prefers not to fulfill Faust's wishes, but rather to separate him from his former existence. He never provides Faust what he wants, instead he attempts to infatuate Faust with superficial indulgences, and thus enmesh him in deep guilt.

In the scene in Auerbach's Cellar, Mephistopheles takes Faust to a tavern, where Faust is bored and disgusted by the drunken revelers. Mephistopheles realizes his first attempt to lead Faust to ruin is aborted, for Faust expects something different.

Gretchen's tragedy

[edit]Witch's Kitchen

Mephistopheles takes Faust to see a witch, who—with the aid of a magic potion brewed under the spell of the Hexen-Einmaleins (witch's algebra)—turns Faust into a handsome young man. In a magic mirror, Faust sees the image of a woman, presumably similar to the paintings of the nude Venus by Italian Renaissance masters like Titian or Giorgione, which awakens within him a strong erotic desire. In contrast to the scene in Auerbach's Cellar, where men behaved as animals, here the witch's animals behave as men.

Street

Faust spies Margarete, known as "Gretchen", on the street in her town, and demands Mephistopheles procure her for him. Mephistopheles foresees difficulty, due to Margarete's uncorrupted nature. He leaves jewellery in her cabinet, arousing her curiosity.

Evening

Margarete brings the jewellery to her mother, who is wary of its origin, and donates it to the Church, much to Mephistopheles's fury.

The Neighbour's House

Mephistopheles leaves another chest of jewellery in Gretchen's house. Gretchen innocently shows the jewellery to her neighbour Marthe. Marthe advises her to secretly wear the jewellery there, in her house. Mephistopheles brings Marthe the news that her long absent husband has died. After telling the story of his death to her, she asks him to bring another witness to his death in order to corroborate it. He obliges, having found a way for Faust to encounter Gretchen.

Garden

At the garden meeting, Marthe flirts with Mephistopheles, and he is at pains to reject her unconcealed advances. Gretchen confesses her love to Faust, but she knows instinctively that his companion (Mephistopheles) has improper motives.

Forest and Cave Faust's monologue is juxtaposed with Gretchen's soliloquy at the spinning wheel in the following scene. This monologue is connected thematically with Faust's opening monologue in his study; he directly addresses the Earth Spirit.

Gretchen's Chamber

Gretchen is at her spinning wheel, thinking of Faust. The text of this scene was notably put to music by Franz Schubert in the lied Gretchen am Spinnrade, Op. 2, D. 118 (1814).

Marthe's Garden

Gretchen presents Faust with the famous question "What is your way about religion, pray?"[4] She wants to admit Faust to her room, but fears her mother. Faust gives Gretchen a bottle containing a sleeping potion to give to her mother. Catastrophically, the potion turns out to be poisonous, and the tragedy takes its course.

"At the Well" and "By the City Wall"

In the following scenes, Gretchen has the first premonitions that she is pregnant as a result of Faust's seduction. Gretchen and Lieschen's discussion of an unmarried mother, in the scene at the Well, confirms the reader's suspicion of Gretchen's pregnancy. Her guilt is shown in the final lines of her speech: "Now I myself am bared to sin! / Yet all of it that drove me here, / God! Was so innocent, was so dear!"[5] In "By the City Wall", Gretchen kneels before the statue of the Virgin and prays for help. She uses the opening of the Stabat Mater, a Latin hymn from the thirteenth century thought to be authored by Jacopone da Todi.

Night: Street in Front of Gretchen's Door

Valentine, Gretchen's brother, is enraged by her liaison with Faust and challenges him to a duel. Guided by Mephistopheles, Faust defeats Valentine, who curses Gretchen just before he dies.

Cathedral

Gretchen seeks comfort in the church, but she is tormented by an Evil Spirit who whispers in her ear, reminding her of her guilt. This scene is generally considered to be one of the finest in the play.[citation needed] The Evil Spirit's tormenting accusations and warnings about Gretchen's eternal damnation at the Last Judgement, as well as Gretchen's attempts to resist them, are interwoven with verses of the hymn Dies irae (from the traditional Latin text of the Requiem Mass), which is being sung in the background by the cathedral choir. Gretchen ultimately falls into a faint.

Walpurgis Night and Walpurgis Night's Dream

A folk belief holds that during the Walpurgis Night (Walpurgisnacht) on the night of 30 April—the eve of the feast day of Saint Walpurga—witches gather on the Brocken mountain, the highest peak in the Harz Mountains, and hold revels with the Devil. The celebration is a Bacchanalia of the evil and demonic powers.

At this festival, Mephistopheles draws Faust from the plane of love to the sexual plane, to distract him from Gretchen's fate. Mephistopheles is costumed here as a Junker and with cloven hooves. Mephistopheles lures Faust into the arms of a naked young witch, but he is distracted by the sight of Medusa, who appears to him in "his lov'd one's image": a "lone child, pale and fair", resembling "sweet Gretchen".

"Dready Day. A Field" and "Night. Open Field"

The first of these two brief scenes is the only section in the published drama written in prose, and the other is in irregular unrhymed verse. Faust has apparently learned that Gretchen has drowned the newborn child in her despair, and has been condemned to death for infanticide. Now she awaits her execution. Faust feels culpable for her plight and reproaches Mephistopheles, who however insists that Faust himself plunged Gretchen into perdition: "Who was it that plunged her to her ruin? I or you?" However, Mephistopheles finally agrees to assist Faust in rescuing Gretchen from her cell.

Dungeon

Mephistopheles procures the key to the dungeon, and puts the guards to sleep, so that Faust may enter. Gretchen is no longer subject to the illusion of youth upon Faust, and initially does not recognize him. Faust attempts to persuade her to escape, but she refuses because she recognizes that Faust no longer loves her and only pities her. When she sees Mephistopheles, she is frightened and implores to heaven: "Judgment of God! To thee my soul I give!". Mephistopheles pushes Faust from the prison with the words: "She now is judged!" (Sie ist gerichtet!). Gretchen's salvation, however, is proven by voices from above: "Is saved!" (Ist gerettet!).

References

[edit]- ^ Portor, Laura Spencer (1917). The Greatest Books in the World: Interpretative Studies. Chautauqua, New York: Chautauqua Press. p. 82.

- ^ Williams, John R., Goethe's Faust, Allen & Unwin, 1987, p. 66. ISBN 9780048000439

- ^ Faust, Norton Critical Edition 1976, lines 1699–1706, translated by Walter Arndt OCLC 614612272 ISBN 9780393044249

- ^ Faust, Norton Critical Edition, line 3415

- ^ Faust, Norton Critical Edition, lines 3584–3586

External links

[edit] German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Faust – Der Tragödie erster Teil

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Faust – Der Tragödie erster Teil Works related to Faust (Goethe) at Wikisource

Works related to Faust (Goethe) at Wikisource

- Faust at Project Gutenberg

- Faust Parts I & II, complete translation, with line numbers and full stage directions