Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fort Vasai

View on Wikipedia

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (February 2008) |

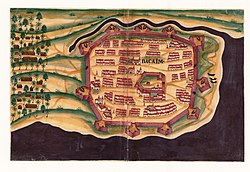

Fort Vasai (Vasai killa in Marathi, Fort Vasai in English) is a ruined fort in the town of Vasai (Bassein), Konkan Division, Maharashtra, India. The structure was formally christened as the Fort of St. Sebastian in the Indo-Portuguese era. The fort is a monument of national importance and is protected by the Archaeological Survey of India.[1]

Key Information

The fort and the town are accessible via the Vasai Railway Station which itself is in the city of Vasai-Virar, and lies to the immediate north of the city of Mumbai (Bombay). The Naigaon Railway Station is on the Western Railway line (formerly the Bombay-Baroda railway) in the direction of the Virar railway station.

History

[edit]

Pre-Portuguese Era

[edit]The Greek merchant Cosma Indicopleustes is known to have visited the areas around Vasai in the 6th century, and the Chinese traveller Xuanzang in June or July 640. According to historian José Gerson da Cunha, during this time, Vasai and its surrounding areas appeared to have been ruled by the Chalukya dynasty of Karnataka.[2] Until the 11th century, several Arabian geographers had mentioned references to towns nearby, like Thane and Nala Sopara, but no references had been made to Vasai.[3] Vasai was later ruled by the Silhara dynasty of Konkan and eventually passed to the Yadava dynasty. It was the head of district under the Yadavas (1184–1318). Later, being conquered by the Gujarat Sultanate,[4] a few years later Barbosa (1514) described it under the name Baxay (pronounced Basai) as a town with a good seaport belonging to the king of Gujarat.[5]

Portuguese Era

[edit]The Portuguese Armadas first reached the west coast of India after the discovery of the Cape route by Vasco da Gama; he landed at Calicut in 1498. For several years after their arrival, they had been consolidating their power in north and south Konkan, in and around present-day Bombay and Goa. They had established their capital at Velha Goa, captured from the Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur in 1510. According to historian Manuel de Faria e Sousa, the coast of Bassein (Vasai) was first visited by them in 1509, when Francisco de Almeida, on his way to Dio, captured a ship off Bombay Harbour, with 24 citizens of the Sultan of Guzerat aboard it.

In 1530, Portuguese captain António da Silvera burnt the city of Vasai and continued the burning and looting up to nearby Bombaim, when the King of Thana surrendered the islands of Mahim, and Bombaim. Subsequently, the towns of Thana, Bandora, Mahim and Bombay were brought under Portuguese control.[6][unreliable source?] In 1531, António de Saldanha while returning from Gujarat to Goa, set fire to Baçaim again — to punish the Sultanate of Gujarat's King Bahadur Shah for not ceding Diu.

In 1533, Diogo (Heytor) de Sylveira, burnt the entire sea coast from Bandora, Thana, Baçaim, to Surat. Diogo de Sylveira returned to Goa with 4000 slaves and spoils.[7][unreliable source?] For the Portuguese, Diu was an important island to protect their trade, which they had to capture. While devising the means to capture Diu, the Portuguese governor of India Nuno da Cunha found out that the governor of Diu was Malik Ayaz whose son Malik Tokan was fortifying Baçaim with 14,000 men.

Nuno da Cunha saw this fortification as a threat. He assembled a fleet of 150 ships with 4000 men and sailed to Baçaim. Upon seeing such a formidable naval power, Malik Tokan made overtures of peace to Nuno da Cunha. The peace overtures were rejected. Malik Tokan had no option but to fight the Portuguese. The Portuguese landed north of the Baçaim and invaded the fortification. Even though the Portuguese were numerically insignificant, they fought with skill and valor killing off most of the enemy soldiers while losing only a handful of their own.[8][unreliable source?]

On 23 December 1534, the Sultan of Gujarat Bahadur Shah signed a treaty with the Portuguese and ceded Baçaim with its dependencies of Salsette, Bombaim (Bombay), Parel, Vadala, Siao (Sion), Vorli (Worli), Mazagao (Mazgaon), Thana, Bandra, Mahim, and Caranja (Uran).[9][unreliable source?] In 1536, Nuno da Cunha appointed his brother-in-law Garcia de Sá as the first Captain/Governor of Baçaim. The first cornerstone for the Fort was laid by António Galvão. In 1548, the Governorship of Baçaim was passed on to Jorge Cabral.[8]

Treaty of Vasai (1534)

[edit]The Treaty of Vasai (1534) was signed by Sultan Bahadur of Gujarat and the Kingdom of Portugal on 23 December 1534, while on board the galleon São Mateus. Based on the terms of the agreement, the Portuguese Empire gained control of the city of Vasai (Bassein), as well as its territories, islands, and seas. The Bombay islands under Portuguese control include Colaba, Old Woman's Island, Mumbai (Bombay), Mazagaon, Worli, Matunga, Mahim. Salsette, Diu, Trombay and Chaul were other territories controlled and settled by the Portuguese.

At the time, the cession of Mumbai (Bombay) was of minor importance, but retroactively it gained a place on the world map when the place passed from the Portuguese to the East India Company in 1661, as part of the dowry of Catherine Braganza. It became a major trade center, the treaty's most important long-term result.

Vasai (Bassein) became the northern territory's headquarters after the 16th-century treaty with Bahadur Shah of Gujarat. In the Portuguese era, the fort was styled as the Northern Court (Corte da Norte), second only to the Portuguese viceroy of the East in the city of Velha Goa. For over 150 years, the Portuguese presence made the surrounding area a vibrant and opulent city.[10][11] The Bassein and its surroundings were the largest Portuguese territory, including places such as Chaul-Revdanda, Caranja, the Bombay Archipelago, Bandra Island, Juhu Island, Salsette Island including the city of Thane, Dharavi Island, the Bassein archipelago, Daman and Diu.

Construction of the fortress

[edit]In the second half of the 16th century, the Portuguese built a new fortress enclosing a whole town within the fort walls. The fort included 10 bastions, of these nine, were named Cavalheiro, Nossa Senhora dos Remédios, Reis Magos Santiago, São Gonçalo, Madre de Deus, São João, Elefante, São Pedro, São Paulo and São Sebastião, São Sebastião was also called "Porta Pia" or the pious door of Baçaim. It was through this bastion that the Marathas would enter to defeat the Portuguese. There were two medieval gateways, one on the seaside called Porta do Mar with massive teak gates cased with iron spikes and the other one called Porta da Terra. There were ninety pieces of artillery, 27 of which were made of bronze, and seventy mortars, 7 of these mortars were made of bronze. The port was defended by 21 gunboats each carrying 16 to 18 guns. This fort stands today with the outer shell and ruins of churches.[12][unreliable source?] In 1548, St. Francisco Xavier stopped in Baçaim, and a portion of the Baçaim population was converted to Christianity. In Salsette Island, the Portuguese built 9 churches: Nirmal (1557), Remedi (1557), Sandor (1566), Agashi (1568), Nandakhal (1573), Papdi (1574), Pali (1595), Manickpur (1606), Mercês (1606). All these beautiful churches are still used by the Christian community of Vasai. In 1573 alone 1600 people were baptized.[7]

17th Century

[edit]

As Baçaim prospered under the Portuguese, it came to be known as "a Corte do Norte" or "Court of the North", it became a resort to "hidalgos" or noblemen and richest merchants of Portuguese India. Baçaim became so famous that a great Portuguese man would be called "Fidalgo ou Cavalheiro de Baçaim" or "Nobleman of Bassein".[13] Baçaim during the Portuguese period was known for the refinement and wealth and splendor of its buildings, palaces and for the beauty of its churches. The Bassein fort which now lies in ruins was the administrative center and court of the northern province, and was subordinate only to Velha Goa in the south, the capital of the East Indies or the eastern faction of the Portuguese empire. The northern province consisted of a territory that extended as far as 100 kilometers along the coast, in between Damaon (Daman) and Chaul (Colaba district), and in some places extended 30-50 kilometers inland. It was the most productive Indian area under Portuguese rule. [citation needed]

In 1618, Baçaim suffered from a succession of disasters. First, it was struck by a plague then on 15 May, the city was struck by a deadly cyclone. It caused considerable damage to the boats and houses, and thousands of coconut trees were uprooted and flattened, monsoon winds had pushed brackish seawater inland. Many churches and convents of the Franciscans and Augustinians were affected by the disaster. The roofs of three of the largest churches in Bassein city including the seminary and the chapel of the Jesuits were ripped off, making the structure almost beyond repair. This storm was followed by so complete a failure of rain which resulted in famine-like conditions. In a few months, the situation grew so precarious that parents were openly selling their children to Muslim brokers into slavery rather than starving them to death. The practice was stopped by the Jesuits, partly by saving from their own scanty allowances and partly by donations from the rich.[14] In 1634, Baçaim's population numbered about 400 Portuguese families, 200 Indian Christian families and 1800 slaves (Indians and Africans). In 1674, Bassein had 2 colleges, 4 convents, and 6 churches.[15]

In 1674, 600 Arab pirates from Muscat landed at Baçaim. The fort garrison remained within the fort walls. The pirates plundered all the churches outside of the fort walls and spared no violence and cruelty towards the people of Baçaim.[16][unreliable source?] In 1674, More Pundit stationed himself in Kalyan, and forced the Portuguese to pay him one-fourth of Baçaim's revenues. Two years later, Shivaji advanced near Saiwan.[17] As the Portuguese power waned towards the end of the 17th century, Baçaim suffered considerably. The importance of Baçaim was reduced by the transfer of neighboring Bombaim island to the British in 1665. The East India Company had been coveting the relatively safe Bombay Harbour for many years, even before their trading post was affected by the Sack of Surat. Bombaim was finally acquired by them through the royal dowry of Catherine Braganza, before that they had ventured to seize it by force in 1626 and had urged the directors of the East India Company to purchase it in 1652.[18][unreliable source?]

Their colonization efforts gradually divided the lands into estates or fiefs, which were granted as rewards to deserving individuals or to religious orders on a system known as foramen to whereby the grantees were bound to furnish military aid to the king of Portugal or where military service was not deemed necessary, to pay a certain rent.[19] Portuguese administration saw frequent transfers of officers and the practice of allowing the great nobles to remain at court and administer their provinces.

The Portuguese trade monopoly with Europe could henceforth last only so long as no European rival came upon the scene.[20]

The community known as the "Bombay East Indians" were called Norteiros (Northern men) after the Court of the North, based in the fort.

Maratha Era

[edit]

In the 18th century, the Bassein Fort was taken over by the Maratha Empire under Peshwa Baji Rao's brother Chimaji Appa and fell in 1739 after the Battle of Vasai.

British Era

[edit]Treaty of Vasai (1802)

[edit]The Treaty of Vasai (1802) was a pact signed on 31 December 1802 between the British East India Company and Baji Rao II, the Maratha Peshwa of Pune in India after the Battle of Pune. The treaty was a decisive step in the dissolution of the Maratha Empire.

Present

[edit]The fort is a major tourist attraction in the region. The ramparts overlook what is alternatively called the Vasai Creek and the Bhayandar Creek and are almost complete, though overgrown by vegetation. Several watch-towers still stand, with safe staircases leading up. The Buildings inside the fort are in ruins, although there are enough standing walls to give a good idea of the floor plans of these structures. Some have well-preserved facades. In particular, many of the arches have weathered the years remarkably well. They are usually decorated with carved stones, some weathered beyond recognition, others still displaying sharp chisel marks.

Three chapels inside the fort are still recognisable. They have facades typical of 17th-century Churches. The southernmost of these has a well-preserved barrel-vaulted ceiling. Besides all the structures, tourists often also observe the nature that has taken over much of the fort. Butterflies, birds, plants and reptiles can all be observed.

The fort is also a popular shooting location for Bollywood movies and songs. The Bollywood hit songs Kambakkht Ishq from Pyaar Tune Kya Kiya, Poster Lagwa Do from Luka Chuppi are Bollywood songs short at the fort. Movies such as Josh starring Shah Rukh Khan, and Love Ke Liye Kuch Bhi Karega have a number of scenes from the fort. Other films shot here include Khamoshi: The Musical and Ram Gopal Verma's Aag. The fort was also one of the shooting locations for the international hit song Hymn for the Weekend by British band Coldplay. The fort showcased at the start and in between is the Vasai Fort.[21][22] The video features Beyoncé and Indian actress Sonam Kapoor.[23] The video has over 960 million views on YouTube as of July 2018, becoming the second most-viewed music video for Coldplay (after "Something Just like This").

The Archaeological Survey of India has started restoration work of the fort, although the quality of the work has been severely criticised by "conservation activists".[citation needed]

Inscriptions at Fort Baçaim

[edit]Excluding the gravestones at the Jesuit College, there are about 2 inscriptions at the fort •Inscription 1. this inscription is located on the ramparts of the fort

this inscription talks about the first Captain i.e, Garcia de Sá on the order of the Governor General Nuno Da Cunha to build this fort.

•Inscription 2.

This inscription could be like a guide to those 'houses' as the first line of the inscription says, 'ES AS CASAS SE' which means 'these are the houses....' but still not much information is available on it.

Accessibility

[edit]

To visit the Vasai Fort,[24] take a Western Railways train bound to Virar from Churchgate in Mumbai and alight at the Vasai Road Railway Station. If you are departing from the Central Railway or Central Railway Harbour Line, then you have to switch to the Western Railway line at either Dadar, Bandra or Andheri. Another railway line connects the Central and the Western Railways lines from Vasai Road Railway Station to Diva, a stop just beyond Thane city on the Central Railway line, and long-distance passenger trains travelling this route also carry commuters between the two lines. There is a railway station named Kopar between Diva and Dombivli. Passengers travelling from Thane or Kalyan can alight at Kopar and walk up the staircase and to Platform No. 3 where they can catch the Diva to Vasai train. The Vasai Road station is only an hour by train from Kopar station. Currently, there are 5 trains daily which goes to Vasai Road from Dombivli, Diva and Panvel and 5 trains from Vasai Road to Diva and Panvel. There is a State Road Transport Bus Terminus & Station adjacent and to the immediate west of the Vasai Road Railway Station in Manickpur-Navghar. The destination for buses going to the Vasai Fort is "Killa Bunder" or "Fort Jetty/Quay". There are buses every half-hour. Tickets cost ₹15 per person and you can alight at the last stop and walk around. Auto rickshaws are also available, which can be hired from the western entrance to the railway station but cost more per head and are regarded as unsafe in that they are usually congested. Auto rickshaws are also available, which can be hired from the main road outside the station but it is ₹ 40 per person.[25]

Gallery

[edit]Some fauna and flora inside the fort:

-

Baobab tree at the seaside entrance

-

Baby caterpillars feeding on leaves

-

Some wildflowers

-

Spider from the family Araneidae feasting on a butterfly

-

African Hoopoe

-

Agamid Lizard

See also

[edit]- Military history of Bassein

- Treaty of Bassein (1534)

- Treaty of Bassein (1802)

- Portuguese India

- Chimaji Appa

- Battles involving the Maratha Empire

- List of Maratha dynasties and states

- Marathi People

- Maratha Army

- Maratha Navy

- Maratha titles

- Military history of India

- List of forts in Maharashtra

- List of forts in India

- List of Jesuit sites

References

[edit]- ^ Monument #110, Mumbai Circle, ASI: http://asi.nic.in/asi_monu_alphalist_maharashtra_mumbai.asp

- ^ Da Cunha 1999, p. 129

- ^ Da Cunha 1999, p. 130

- ^ Da Cunha 1999, p. 131

- ^ "Chapter 19: Places". Thane District Gazetteer. 20 December 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Ramerini, Marco (9 February 2014). "The Portuguese in Bassein (Baçaim, Vasai): the ruins of a Portuguese town in India". Colonialvoyage.com. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Vasai Fort - Bassein Fort – Solotravellers". Thesolotravellers.in. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ a b "History of Vasai - 2984 Words". Studymode.com. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Nuno da Cunha & Treaty of Bassein - General Knowledge Today". Gktoday.in.

- ^ "Vasai Fort". Maharashtra Tourism. Archived from the original on 17 September 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Vasai Fort". Maharashtra Tourism. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Travel India". Travelindiapro.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Asiatic Society of Bombay (3 March 1875). "Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay". Asiatic Society of Bombay – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Places of Interest : Bassein". Gazetteers.mahaeashtra.gov.in. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Greater Bombay District : Ancient History". Cultural.maharashtra.gov.in. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "The English in Western India - Piracy". Scribd.com.

- ^ Campbell, James MacNabb; Enthoven, R. E. (Reginald Edward) (3 March 1883). "Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency". Bombay : Gov. Central Press – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Did You Know Mumbai Was Given As Dowry To The British By The Portuguese?". Scoopwhoop.com. 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Full text of "Imperial Gazetteer of India Provincial Series Bombay Presidency Vol-i"". Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "portugal no mundo". Portugalweb.net.

- ^ Mor, Ben (29 January 2016). "Ben Mor on Instagram". Instagram. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Black Dog Films on Instagram". Instagram. Black Dog Films. 29 January 2016. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Lohana, Avinash (28 January 2016). "Sonam and Beyonce feature in new 'Coldplay' single". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Vasai Fort - How to go & history of Vasai Fort". YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Vasai Fort - How to go, places to visit, things to do". Time to Travel. 1 January 2010. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

External links

[edit]- History of Vasai

- Mumbai - The Cosmopolitan City Archived 14 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Mumbai Customs - History

Bibliography

[edit]- Da Cunha, J. Gerson (1993). Notes on the History and Antiquities of Chaul and Bassein. Asian Educational Services.

- Rossa, Walter (2012). "Vasai Fort: Historical Background and Urbanism". Heritage of Portuguese Influence. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Mendiratta, Sidh Losa (2012). "St. Sebastian Fort: Military Architecture". Heritage of Portuguese Influence. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Mendiratta, Sidh Losa (2012). "Dispositivos do Sistema Defensivo da Província do Norte do Estado da Índia (1521-1739)". PhD Thesis, Coimbra University.

Fort Vasai

View on GrokipediaLocation and Strategic Importance

Geographical Position

Fort Vasai is located in Vasai taluka, Palghar district, Maharashtra, India, approximately 50 kilometers north of Mumbai on the western coastline of the [Arabian Sea](/page/Arabian Sea).[1] The site occupies a strategic coastal position surrounded by seawater on three sides, with a moat protecting the landward approach.[1][4] Its geographical coordinates are approximately 19°19′50″N 72°48′52″E.[4] The fort lies near the mouth of the Vasai Creek, which connects to the [Arabian Sea](/page/Arabian Sea), contributing to its historical defensibility.[4]Defensive Layout and Natural Advantages

Fort Vasai's natural defenses derived primarily from its coastal position, where the Arabian Sea encircled three sides of the 110-acre site, restricting landward access to a single vulnerable front.[1] This configuration, augmented by the adjacent Vasai Creek, formed effective water barriers that impeded large-scale assaults and facilitated monitoring of maritime approaches via watchtowers offering panoramic views.[5][1] The terrain's isolation by water also constrained enemy logistics during sieges, as observed in historical conflicts where supply routes were severed.[5] Complementing these geographical advantages, the Portuguese engineered a robust defensive layout featuring a 4.5-kilometer perimeter wall constructed from stone, designed to enclose the entire complex and withstand prolonged attacks.[4][1] Eleven bastions punctuated the walls, positioned to provide overlapping fields of fire and enfilade coverage against advancing forces, with key structures such as the towers of San Sebastian and Remedios oriented toward northern threats.[4][5] A seawater-filled moat fortified the landward side, channeling tidal flows to maintain a persistent obstacle that integrated with the surrounding aquatic features.[4] The main gate, facing the creek, incorporated additional ramparts that remained largely intact, underscoring the system's emphasis on layered, impenetrable barriers.[5][1]