Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

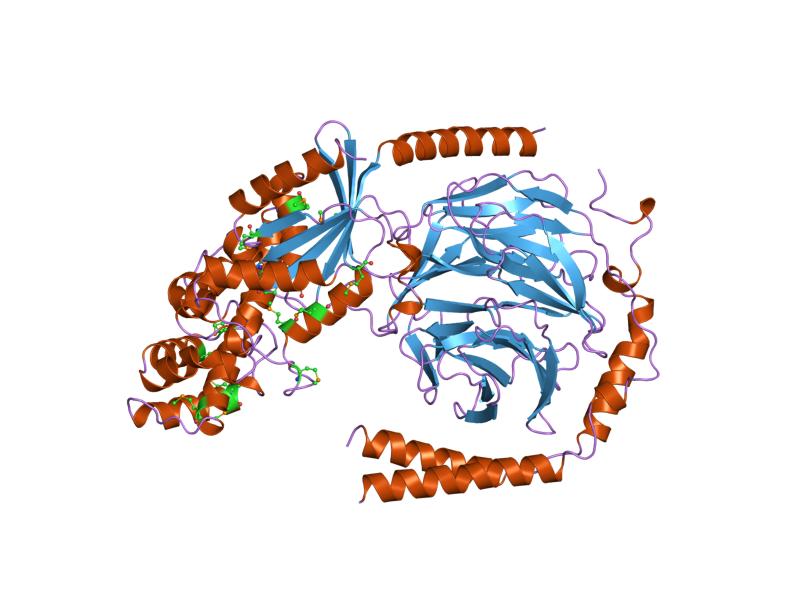

G alpha subunit

View on Wikipedia| G-alpha | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

heterotrimeric complex of a gt-alpha/gi-alpha chimera and the gt-beta-gamma subunits | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | G-alpha | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00503 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0023 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001019 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1gia / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| CDD | cd00066 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

G alpha subunits are one of the three types of subunit of guanine nucleotide binding proteins, which are membrane-associated, heterotrimeric G proteins.[1]

Background

[edit]G proteins and their receptors (GPCRs) form one of the most prevalent signaling systems in mammalian cells, regulating systems as diverse as sensory perception, cell growth and hormonal regulation.[2] At the cell surface, the binding of ligands such as hormones and neurotransmitters to a GPCR activates the receptor by causing a conformational change, which in turn activates the bound G protein on the intracellular-side of the membrane. The activated receptor promotes the exchange of bound GDP for GTP on the G protein alpha subunit. GTP binding changes the conformation of switch regions within the alpha subunit, which allows the bound trimeric G protein (inactive) to be released from the receptor, and to dissociate into active alpha subunit (GTP-bound) and beta/gamma dimer. The alpha subunit and the beta/gamma dimer go on to activate distinct downstream effectors, such as adenylyl cyclase, phosphodiesterases, phospholipase C, and ion channels. These effectors in turn regulate the intracellular concentrations of secondary messengers, such as cAMP, diacylglycerol, sodium or calcium cations, which ultimately lead to a physiological response, usually via the downstream regulation of gene transcription. The cycle is completed by the hydrolysis of alpha subunit-bound GTP to GDP, resulting in the re-association of the alpha and beta/gamma subunits and their binding to the receptor, which terminates the signal.[3] The length of the G protein signal is controlled by the duration of the GTP-bound alpha subunit, which can be regulated by RGS (regulator of G protein signalling) proteins or by covalent modifications.[4]

Forms of subunit

[edit]There are several isoforms of each subunit, many of which have splice variants, which together can make up hundreds of combinations of G proteins. The specific combination of subunits in heterotrimeric G proteins affects not only which receptor it can bind to, but also which downstream target is affected, providing the means to target specific physiological processes in response to specific external stimuli.[5][6] G proteins carry lipid modifications on one or more of their subunits to target them to the plasma membrane and to contribute to protein interactions.

This family consists of the G protein alpha subunit, which acts as a weak GTPase. G protein classes are defined based on the sequence and function of their alpha subunits, which in mammals fall into several sub-types: G(S)alpha, G(Q)alpha, G(I)alpha, transducin and G(12)alpha; there are also fungal and plant classes of alpha subunits.[citation needed] The alpha subunit consists of two domains: a GTP-binding domain and a helical insertion domain (InterPro: IPR011025). The GTP-binding domain is homologous to Ras-like small GTPases, and includes switch regions I and II, which change conformation during activation. The switch regions are loops of alpha-helices with conformations sensitive to guanine nucleotides. The helical insertion domain is inserted into the GTP-binding domain before switch region I and is unique to heterotrimeric G proteins. This helical insertion domain functions to sequester the guanine nucleotide at the interface with the GTP-binding domain and must be displaced to enable nucleotide dissociation.

References

[edit]- ^ Preininger AM, Hamm HE (February 2004). "G protein signaling: insights from new structures". Sci. STKE. 2004 (218): re3. doi:10.1126/stke.2182004re3. PMID 14762218. S2CID 36008459.

- ^ Roberts DJ, Waelbroeck M (September 2004). "G protein activation by G protein coupled receptors: ternary complex formation or catalyzed reaction?". Biochem. Pharmacol. 68 (5): 799–806. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.044. PMID 15294442.

- ^ Svoboda P, Teisinger J, Novotný J, Bourová L, Drmota T, Hejnová L, Moravcová Z, Lisý V, Rudajev V, Stöhr J, Vokurková A, Svandová I, Durchánková D (2004). "Biochemistry of transmembrane signaling mediated by trimeric G proteins". Physiol Res. 53 Suppl 1: S141–52. PMID 15119945.

- ^ Chen CA, Manning DR (March 2001). "Regulation of G proteins by covalent modification". Oncogene. 20 (13): 1643–52. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204185. PMID 11313912.

- ^ Hildebrandt JD (August 1997). "Role of subunit diversity in signaling by heterotrimeric G proteins". Biochem. Pharmacol. 54 (3): 325–39. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(97)00269-4. PMID 9278091.

- ^ Albert PR, Robillard L (May 2002). "G protein specificity: traffic direction required". Cell. Signal. 14 (5): 407–18. doi:10.1016/S0898-6568(01)00259-5. PMID 11882385.