Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Phase (matter)

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

| Part of a series on |

| Chemistry |

|---|

|

In the physical sciences, a phase is a region of material that is chemically uniform, physically distinct, and (often) mechanically separable. In a system consisting of ice and water in a glass jar, the ice cubes are one phase, the water is a second phase, and the humid air is a third phase over the ice and water. The glass of the jar is a different material, in its own separate phase. (See state of matter § Glass.)

More precisely, a phase is a region of space (a thermodynamic system), throughout which all physical properties of a material are essentially uniform.[1][2]: 86 [3]: 3 Examples of physical properties include density, index of refraction, magnetization and chemical composition.

The term phase is sometimes used as a synonym for state of matter, but there can be several immiscible phases of the same state of matter (as where oil and water separate into distinct phases, both in the liquid state).

Types of phases

[edit]

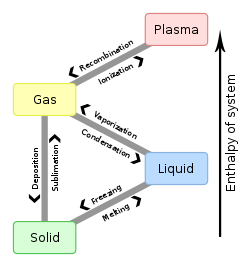

Distinct phases may be described as different states of matter such as gas, liquid, solid, plasma or Bose–Einstein condensate. Useful mesophases between solid and liquid form other states of matter.

Distinct phases may also exist within a given state of matter. As shown in the diagram for iron alloys, several phases exist for both the solid and liquid states. Phases may also be differentiated based on solubility as in polar (hydrophilic) or non-polar (hydrophobic). A mixture of water (a polar liquid) and oil (a non-polar liquid) will spontaneously separate into two phases. Water has a very low solubility (is insoluble) in oil, and oil has a low solubility in water. Solubility is the maximum amount of a solute that can dissolve in a solvent before the solute ceases to dissolve and remains in a separate phase. A mixture can separate into more than two liquid phases and the concept of phase separation extends to solids, i.e., solids can form solid solutions or crystallize into distinct crystal phases. Metal pairs that are mutually soluble can form alloys, whereas metal pairs that are mutually insoluble cannot.

As many as eight immiscible liquid phases have been observed.[a] Mutually immiscible liquid phases are formed from water (aqueous phase), hydrophobic organic solvents, perfluorocarbons (fluorous phase), silicones, several different metals, and also from molten phosphorus. Not all organic solvents are completely miscible, e.g. a mixture of ethylene glycol and toluene may separate into two distinct organic phases.[b]

Phases do not need to macroscopically separate spontaneously. Emulsions and colloids are examples of immiscible phase pair combinations that do not physically separate.

Phase equilibrium

[edit]Left to equilibration, many compositions will form a uniform single phase, but depending on the temperature and pressure even a single substance may separate into two or more distinct phases. Within each phase, the properties are uniform but between the two phases properties differ.

Water in a closed jar with an air space over it forms a two-phase system. Most of the water is in the liquid phase, where it is held by the mutual attraction of water molecules. Even at equilibrium molecules are constantly in motion and, once in a while, a molecule in the liquid phase gains enough kinetic energy to break away from the liquid phase and enter the gas phase. Likewise, every once in a while a vapor molecule collides with the liquid surface and condenses into the liquid. At equilibrium, evaporation and condensation processes exactly balance and there is no net change in the volume of either phase.

At room temperature and pressure, the water jar reaches equilibrium when the air over the water has a humidity of about 3%. This percentage increases as the temperature goes up. At 100 °C and atmospheric pressure, equilibrium is not reached until the air is 100% water. If the liquid is heated a little over 100 °C, the transition from liquid to gas will occur not only at the surface but throughout the liquid volume: the water boils.

Number of phases

[edit]

For a given composition, only certain phases are possible at a given temperature and pressure. The number and type of phases that will form is hard to predict and is usually determined by experiment. The results of such experiments can be plotted in phase diagrams.

The phase diagram shown here is for a single component system. In this simple system, phases that are possible, depend only on pressure and temperature. The markings show points where two or more phases can co-exist in equilibrium. At temperatures and pressures away from the markings, there will be only one phase at equilibrium.

In the diagram, the blue line marking the boundary between liquid and gas does not continue indefinitely, but terminates at a point called the critical point. As the temperature and pressure approach the critical point, the properties of the liquid and gas become progressively more similar. At the critical point, the liquid and gas become indistinguishable. Above the critical point, there are no longer separate liquid and gas phases: there is only a generic fluid phase referred to as a supercritical fluid. In water, the critical point occurs at around 647 K (374 °C or 705 °F) and 22.064 MPa.

An unusual feature of the water phase diagram is that the solid–liquid phase line (illustrated by the dotted green line) has a negative slope. For most substances, the slope is positive as exemplified by the dark green line. This unusual feature of water is related to ice having a lower density than liquid water. Increasing the pressure drives the water into the higher density phase, which causes melting.

Another interesting though not unusual feature of the phase diagram is the point where the solid–liquid phase line meets the liquid–gas phase line. The intersection is referred to as the triple point. At the triple point, all three phases can coexist.

Experimentally, phase lines are relatively easy to map due to the interdependence of temperature and pressure that develops when multiple phases form. Gibbs' phase rule suggests that different phases are completely determined by these variables. Consider a test apparatus consisting of a closed and well-insulated cylinder equipped with a piston. By controlling the temperature and the pressure, the system can be brought to any point on the phase diagram. From a point in the solid stability region (left side of the diagram), increasing the temperature of the system would bring it into the region where a liquid or a gas is the equilibrium phase (depending on the pressure). If the piston is slowly lowered, the system will trace a curve of increasing temperature and pressure within the gas region of the phase diagram. At the point where gas begins to condense to liquid, the direction of the temperature and pressure curve will abruptly change to trace along the phase line until all of the water has condensed.

Interfacial phenomena

[edit]Between two phases in equilibrium there is a narrow region where the properties are not that of either phase. Although this region may be very thin, it can have significant and easily observable effects, such as causing a liquid to exhibit surface tension. In mixtures, some components may preferentially move toward the interface. In terms of modeling, describing, or understanding the behavior of a particular system, it may be efficacious to treat the interfacial region as a separate phase.

Crystal phases

[edit]A single material may have several distinct solid states capable of forming separate phases. Water is a well-known example of such a material. For example, water ice is ordinarily found in the hexagonal form ice Ih, but can also exist as the cubic ice Ic, the rhombohedral ice II, and many other forms. Polymorphism is the ability of a solid to exist in more than one crystal form. For pure chemical elements, polymorphism is known as allotropy. For example, diamond, graphite, and fullerenes are different allotropes of carbon.

Phase transitions

[edit]When a substance undergoes a phase transition (changes from one state of matter to another) it usually either takes up or releases energy. For example, when water evaporates, the increase in kinetic energy as the evaporating molecules escape the attractive forces of the liquid is reflected in a decrease in temperature. The energy required to induce the phase transition is taken from the internal thermal energy of the water, which cools the liquid to a lower temperature; hence evaporation is useful for cooling. See Enthalpy of vaporization. The reverse process, condensation, releases heat. The heat energy, or enthalpy, associated with a solid to liquid transition is the enthalpy of fusion and that associated with a solid to gas transition is the enthalpy of sublimation.

Phases out of equilibrium

[edit]While phases of matter are traditionally defined for systems in thermal equilibrium, work on quantum many-body localized (MBL) systems has provided a framework for defining phases out of equilibrium. MBL phases never reach thermal equilibrium, and can allow for new forms of order disallowed in equilibrium via a phenomenon known as localization protected quantum order. The transitions between different MBL phases and between MBL and thermalizing phases are novel dynamical phase transitions whose properties are active areas of research.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]- ^ One such system is, from the top: mineral oil, silicone oil, water, aniline, perfluoro(dimethylcyclohexane), white phosphorus, gallium, and mercury. The system remains indefinitely separated at 45 °C, where gallium and phosphorus are in the molten state. From Reichardt, C. (2006). Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-3-527-60567-5.

- ^ This phenomenon can be used to help with catalyst recycling in Heck vinylation. See Bhanage, B.M.; et al. (1998). "Comparison of activity and selectivity of various metal-TPPTS complex catalysts in ethylene glycol — toluene biphasic Heck vinylation reactions of iodobenzene". Tetrahedron Letters. 39 (51): 9509–9512. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(98)02225-4.

References

[edit]- ^ Modell, Michael; Robert C. Reid (1974). Thermodynamics and Its Applications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-914861-3.

- ^ Enrico Fermi (2012). Thermodynamics. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-13485-7.

- ^ Clement John Adkins (1983). Equilibrium Thermodynamics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27456-2.