Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Superfluid helium-4

View on WikipediaSuperfluid helium-4 (helium II or He-II) is the superfluid form of helium-4, the most common isotope of the element helium. The substance, which resembles other liquids such as helium I (conventional, non-superfluid liquid helium), flows without friction past any surface, which allows it to continue to circulate over obstructions and through pores in containers which hold it, subject only to its own inertia.[1]

The formation of the superfluid is a manifestation of the formation of a Bose–Einstein condensate of helium atoms. This condensation occurs in liquid helium-4 at a far higher temperature (2.17 K) than it does in helium-3 (2.5 mK) because each atom of helium-4 is a boson particle, by virtue of its zero spin. Helium-3, however, is a fermion particle, which can form bosons only by pairing with itself at much lower temperatures, in a weaker process that is similar to the electron pairing in superconductivity.[2]

History

[edit]Known as a major facet in the study of quantum hydrodynamics and macroscopic quantum phenomena, the superfluidity effect was discovered by Pyotr Kapitsa[3] and John F. Allen, and Don Misener[4] in 1937. Onnes possibly observed the superfluid phase transition on August 2, 1911, the same day that he observed superconductivity in mercury.[5] It has since been described through phenomenological and microscopic theories.

In the 1950s, Hall and Vinen performed experiments establishing the existence of quantized vortex lines in superfluid helium.[6] In the 1960s, Rayfield and Reif established the existence of quantized vortex rings.[7] Packard has observed the intersection of vortex lines with the free surface of the fluid,[8] and Avenel and Varoquaux have studied the Josephson effect in superfluid helium-4.[9] In 2006, a group at the University of Maryland visualized quantized vortices by using small tracer particles of solid hydrogen.[10]

In the early 2000s, physicists created a Fermionic condensate from pairs of ultra-cold fermionic atoms. Under certain conditions, fermion pairs form diatomic molecules and undergo Bose–Einstein condensation. At the other limit, the fermions (most notably superconducting electrons) form Cooper pairs which also exhibit superfluidity. This work with ultra-cold atomic gases has allowed scientists to study the region in between these two extremes, known as the BEC-BCS crossover.

Supersolids may also have been discovered in 2004 by physicists at Penn State University. When helium-4 is cooled below about 200 mK under high pressures, a fraction (≈1%) of the solid appears to become superfluid.[11][12] By quench cooling or lengthening the annealing time, thus increasing or decreasing the defect density respectively, it was shown, via torsional oscillator experiment, that the supersolid fraction could be made to range from 20% to completely non-existent. This suggested that the supersolid nature of helium-4 is not intrinsic to helium-4 but a property of helium-4 and disorder.[13][14] Some emerging theories posit that the supersolid signal observed in helium-4 was actually an observation of either a superglass state[15] or intrinsically superfluid grain boundaries in the helium-4 crystal.[16]

Applications

[edit]Recently[timeframe?] in the field of chemistry, superfluid helium-4 has been successfully used in spectroscopic techniques as a quantum solvent. Referred to as superfluid helium droplet spectroscopy (SHeDS), it is of great interest in studies of gas molecules, as a single molecule solvated in a superfluid medium allows a molecule to have effective rotational freedom, allowing it to behave similarly to how it would in the "gas" phase. Droplets of superfluid helium also have a characteristic temperature of about 0.4 K which cools the solvated molecule(s) to its ground or nearly ground rovibronic state.

Superfluids are also used in high-precision devices such as gyroscopes, which allow the measurement of some theoretically predicted gravitational effects (for an example, see Gravity Probe B).

The Infrared Astronomical Satellite IRAS, launched in January 1983 to gather infrared data was cooled by 73 kilograms of superfluid helium, maintaining a temperature of 1.6 K (−271.55 °C). When used in conjunction with helium-3, temperatures as low as 40 mK are routinely achieved in extreme low temperature experiments. The helium-3, in liquid state at 3.2 K, can be evaporated into the superfluid helium-4, where it acts as a gas due to the latter's properties as a Bose–Einstein condensate. This evaporation pulls energy from the overall system, which can be pumped out in a way completely analogous to normal refrigeration techniques. (See dilution refrigerator)

Superfluid-helium technology is used to extend the temperature range of cryocoolers to lower temperatures. So far, the limit is 1.19 K, but there is a potential to reach 0.7 K.[17]

Properties

[edit]Superfluids, such as helium-4 below the lambda point (known, for simplicity, as helium II), exhibit many unusual properties. A superfluid acts as if it were a mixture of a normal component, with all the properties of a normal fluid, and a superfluid component. The superfluid component has zero viscosity and zero entropy. Application of heat to a spot in superfluid helium results in a flow of the normal component which takes care of the heat transport at relatively high velocity (up to 20 cm/s) which leads to a very high effective thermal conductivity.

Film flow

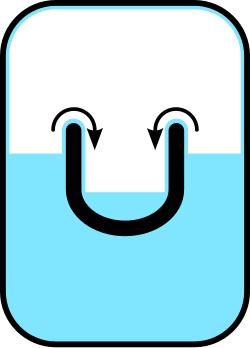

[edit]Many ordinary liquids, like alcohol or petroleum, creep up solid walls, driven by their surface tension. Liquid helium also has this property, but, in the case of He-II, the flow of the liquid in the layer is not restricted by its viscosity but by a critical velocity which is about 20 cm/s. This is a fairly high velocity so superfluid helium can flow relatively easily up the wall of containers, over the top, and down to the same level as the surface of the liquid inside the container, in a siphon effect. It was, however, observed, that the flow through nanoporous membrane becomes restricted if the pore diameter is less than 0.7 nm (i.e. roughly three times the classical diameter of helium atom), suggesting the unusual hydrodynamic properties of He arise at larger scale than in the classical liquid helium.[18]

Rotation

[edit]Another fundamental property becomes visible if a superfluid is placed in a rotating container. Instead of rotating uniformly with the container, the rotating state consists of quantized vortices. That is, when the container is rotated at speeds below the first critical angular velocity, the liquid remains perfectly stationary. Once the first critical angular velocity is reached, the superfluid will form a vortex. The vortex strength is quantized, that is, a superfluid can only spin at certain "allowed" values. Rotation in a normal fluid, like water, is not quantized. If the rotation speed is increased more and more quantized vortices will be formed which arrange in nice patterns similar to the Abrikosov lattice in a superconductor.

Comparison with helium-3

[edit]Although the phenomenologies of the superfluid states of helium-4 and helium-3 are very similar, the microscopic details of the transitions are very different. Helium-4 atoms are bosons, and their superfluidity can be understood in terms of the Bose–Einstein statistics that they obey. Specifically, the superfluidity of helium-4 can be regarded as a consequence of Bose–Einstein condensation in an interacting system. On the other hand, helium-3 atoms are fermions, and the superfluid transition in this system is described by a generalization of the BCS theory of superconductivity. In it, Cooper pairing takes place between atoms rather than electrons, and the attractive interaction between them is mediated by spin fluctuations rather than phonons. (See fermion condensate.) A unified description of superconductivity and superfluidity is possible in terms of gauge symmetry breaking.

Macroscopic theory

[edit]Thermodynamics

[edit]

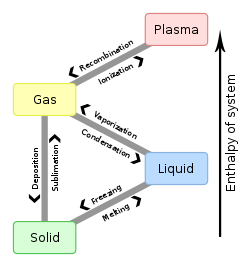

Figure 1 is the phase diagram of 4He.[19] It is a pressure-temperature (p-T) diagram indicating the solid and liquid regions separated by the melting curve (between the liquid and solid state) and the liquid and gas region, separated by the vapor-pressure line. This latter ends in the critical point where the difference between gas and liquid disappears. The diagram shows the remarkable property that 4He is liquid even at absolute zero. 4He is only solid at pressures above 25 bar.

Figure 1 also shows the λ-line. This is the line that separates two fluid regions in the phase diagram indicated by He-I and He-II. In the He-I region the helium behaves like a normal fluid; in the He-II region the helium is superfluid.

The name lambda-line comes from the specific heat – temperature plot which has the shape of the Greek letter λ.[20][21] See figure 2, which shows a peak at 2.172 K, the so-called λ-point of 4He.

Below the lambda line the liquid can be described by the so-called two-fluid model. It behaves as if it consists of two components: a normal component, which behaves like a normal fluid, and a superfluid component with zero viscosity and zero entropy. The ratios of the respective densities ρn/ρ and ρs/ρ, with ρn (ρs) the density of the normal (superfluid) component, and ρ (the total density), depends on temperature and is represented in figure 3.[22] By lowering the temperature, the fraction of the superfluid density increases from zero at Tλ to one at zero kelvins. Below 1 K the helium is almost completely superfluid.

It is possible to create density waves of the normal component (and hence of the superfluid component since ρn + ρs = constant) which are similar to ordinary sound waves. This effect is called second sound. Due to the temperature dependence of ρn (figure 3) these waves in ρn are also temperature waves.

Superfluid hydrodynamics

[edit]The equation of motion for the superfluid component, in a somewhat simplified form,[23] is given by Newton's law

The mass is the molar mass of 4He, and is the velocity of the superfluid component. The time derivative is the so-called hydrodynamic derivative, i.e. the rate of increase of the velocity when moving with the fluid. In the case of superfluid 4He in the gravitational field the force is given by[24][25]

In this expression is the molar chemical potential, the gravitational acceleration, and the vertical coordinate. Thus we get the equation which states that the thermodynamics of a certain constant will be amplified by the force of the natural gravitational acceleration

| 1 |

Eq. (1) only holds if is below a certain critical value, which usually is determined by the diameter of the flow channel.[26][27]

In classical mechanics the force is often the gradient of a potential energy. Eq. (1) shows that, in the case of the superfluid component, the force contains a term due to the gradient of the chemical potential. This is the origin of the remarkable properties of He-II such as the fountain effect.

Fountain pressure

[edit]In order to rewrite Eq.(1) in more familiar form we use the general formula

| 2 |

Here is the molar entropy and the molar volume. With Eq.(2) can be found by a line integration in the – plane. First, we integrate from the origin to , so at . Next, we integrate from to , so with constant pressure (see figure 6). In the first integral and in the second . With Eq.(2) we obtain

| 3 |

We are interested only in cases where is small so that is practically constant. So

| 4 |

where is the molar volume of the liquid at and . The other term in Eq.(3) is also written as a product of and a quantity which has the dimension of pressure

| 5 |

The pressure is called the fountain pressure. It can be calculated from the entropy of 4He which, in turn, can be calculated from the heat capacity. For the fountain pressure is equal to 0.692 bar. With a density of liquid helium of 125 kg/m3 and g = 9.8 m/s2 this corresponds with a liquid-helium column of 56-meter height. So, in many experiments, the fountain pressure has a bigger effect on the motion of the superfluid helium than gravity.

With Eqs.(4) and (5), Eq.(3) obtains the form

| 6 |

Substitution of Eq.(6) in (1) gives

| 7 |

with the density of liquid 4He at zero pressure and temperature.

Eq.(7) shows that the superfluid component is accelerated by gradients in the pressure and in the gravitational field, as usual, but also by a gradient in the fountain pressure.

So far Eq.(5) has only mathematical meaning, but in special experimental arrangements can show up as a real pressure. Figure 7 shows two vessels both containing He-II. The left vessel is supposed to be at zero kelvins () and zero pressure (). The vessels are connected by a so-called superleak. This is a tube, filled with a very fine powder, so the flow of the normal component is blocked. However, the superfluid component can flow through this superleak without any problem (below a critical velocity of about 20 cm/s). In the steady state so Eq.(7) implies

| 8 |

where the indexes and apply to the left and right side of the superleak respectively. In this particular case , , and (since ). Consequently,

This means that the pressure in the right vessel is equal to the fountain pressure at .

In an experiment, arranged as in figure 8, a fountain can be created. The fountain effect is used to drive the circulation of 3He in dilution refrigerators.[28][29]

Heat transport

[edit]Figure 9 depicts a heat-conduction experiment between two temperatures and connected by a tube filled with He-II. When heat is applied to the hot end a pressure builds up at the hot end according to Eq.(7). This pressure drives the normal component from the hot end to the cold end according to

| 9 |

Here is the viscosity of the normal component,[30] some geometrical factor, and the volume flow. The normal flow is balanced by a flow of the superfluid component from the cold to the hot end. At the end sections a normal to superfluid conversion takes place and vice versa. So, heat is transported, not by heat conduction, but by convection. This kind of heat transport is very effective, so the thermal conductivity of He-II is very much better than the best materials. The situation is comparable with heat pipes where heat is transported via gas–liquid conversion. The high thermal conductivity of He-II is applied for stabilizing superconducting magnets such as in the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

Microscopic theory

[edit]Landau two-fluid approach

[edit]L. D. Landau's phenomenological and semi-microscopic theory of superfluidity of helium-4 earned him the Nobel Prize in physics, in 1962. Assuming that sound waves are the most important excitations in helium-4 at low temperatures, he showed that helium-4 flowing past a wall would not spontaneously create excitations if the flow velocity was less than the sound velocity. In this model, the sound velocity is the "critical velocity" above which superfluidity is destroyed. (Helium-4 actually has a lower flow velocity than the sound velocity, but this model is useful to illustrate the concept.) Landau also showed that the sound wave and other excitations could equilibrate with one another and flow separately from the rest of the helium-4, which is known as the "condensate".

From the momentum and flow velocity of the excitations he could then define a "normal fluid" density, which is zero at zero temperature and increases with temperature. At the so-called Lambda temperature, where the normal fluid density equals the total density, the helium-4 is no longer superfluid.

To explain the early specific heat data on superfluid helium-4, Landau posited the existence of a type of excitation he called a "roton", but as better data became available, he considered that the "roton" was the same as a high momentum version of sound.

The Landau theory does not elaborate on the microscopic structure of the superfluid component of liquid helium.[31] The first attempts to create a microscopic theory of the superfluid component itself were done by London[32] and subsequently, Tisza.[33][34] Other microscopical models have been proposed by different authors. Their main objective is to derive the form of the inter-particle potential between helium atoms in superfluid state from first principles of quantum mechanics. To date, a number of models of this kind have been proposed, including: models with vortex rings, hard-sphere models, and Gaussian cluster theories.

Vortex ring model

[edit]Landau thought that vorticity entered superfluid helium-4 by vortex sheets, but such sheets have since been shown to be unstable. Lars Onsager and, later independently, Feynman showed that vorticity enters by quantized vortex lines. They also developed the idea of quantum vortex rings. Arie Bijl in the 1940s,[35] and Richard Feynman around 1955,[36] developed microscopic theories for the roton, which was shortly observed with inelastic neutron experiments by Palevsky. Later on, Feynman admitted that his model gives only qualitative agreement with experiment.[37][38]

Hard-sphere models

[edit]The models are based on the simplified form of the inter-particle potential between helium-4 atoms in the superfluid phase. Namely, the potential is assumed to be of the hard-sphere type.[39][40][41] In these models the famous Landau (roton) spectrum of excitations is qualitatively reproduced.

Gaussian cluster approach

[edit]This is a two-scale approach which describes the superfluid component of liquid helium-4. It consists of two nested models linked via parametric space. The short-wavelength part describes the interior structure of the fluid element using a non-perturbative approach based on the logarithmic Schrödinger equation; it suggests the Gaussian-like behaviour of the element's interior density and interparticle interaction potential. The long-wavelength part is the quantum many-body theory of such elements which deals with their dynamics and interactions.[42] The approach provides a unified description of the phonon, maxon and roton excitations, and has noteworthy agreement with experiment: with one essential parameter to fit one reproduces at high accuracy the Landau roton spectrum, sound velocity and structure factor of superfluid helium-4.[43] This model utilizes the general theory of quantum Bose liquids with logarithmic nonlinearities[44] which is based on introducing a dissipative-type contribution to energy related to the quantum Everett–Hirschman entropy function.[45][46]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Superfluidity". Encyclopedia of Condensed Matter Physics. Elsevier. 2005. pp. 128–133.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1996 - Advanced Information". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Kapitza, P. (1938). "Viscosity of Liquid Helium Below the λ-Point". Nature. 141 (3558): 74. Bibcode:1938Natur.141...74K. doi:10.1038/141074a0. S2CID 3997900.

- ^ Allen, J. F.; Misener, A. D. (1938). "Flow of Liquid Helium II". Nature. 142 (3597): 643. Bibcode:1938Natur.142..643A. doi:10.1038/142643a0. S2CID 4135906.

- ^ van Delft, Dirk; Kes, Peter (September 1, 2010). "The discovery of superconductivity". Physics Today. 63 (9): 38–43. Bibcode:2010PhT....63i..38V. doi:10.1063/1.3490499. ISSN 0031-9228.

- ^ Hall, H. E.; Vinen, W. F. (1956). "The Rotation of Liquid Helium II. II. The Theory of Mutual Friction in Uniformly Rotating Helium II". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 238 (1213): 215. Bibcode:1956RSPSA.238..215H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1956.0215. S2CID 120738827.

- ^ Rayfield, G.; Reif, F. (1964). "Quantized Vortex Rings in Superfluid Helium". Physical Review. 136 (5A) A1194. Bibcode:1964PhRv..136.1194R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.136.A1194.

- ^ Packard, Richard E. (1982). "Vortex photography in liquid helium" (PDF). Physica B. 109–110: 1474–1484. Bibcode:1982PhyBC.109.1474P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.210.8701. doi:10.1016/0378-4363(82)90510-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ Avenel, O.; Varoquaux, E. (1985). "Observation of Singly Quantized Dissipation Events Obeying the Josephson Frequency Relation in the Critical Flow of Superfluid ^{4}He through an Aperture". Physical Review Letters. 55 (24): 2704–2707. Bibcode:1985PhRvL..55.2704A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.2704. PMID 10032216.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bewley, Gregory P.; Lathrop, Daniel P.; Sreenivasan, Katepalli R. (2006). "Superfluid helium: Visualization of quantized vortices" (PDF). Nature. 441 (7093): 588. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..588B. doi:10.1038/441588a. PMID 16738652. S2CID 4429923.

- ^ E. Kim and M. H. W. Chan (2004). "Probable Observation of a Supersolid Helium Phase". Nature. 427 (6971): 225–227. Bibcode:2004Natur.427..225K. doi:10.1038/nature02220. PMID 14724632. S2CID 3112651.

- ^ Moses Chan's Research Group. "Supersolid Archived 2013-04-08 at the Wayback Machine." Penn State University, 2004.

- ^ Sophie, A; Rittner C (2006). "Observation of Classical Rotational Inertia and Nonclassical Supersolid Signals in Solid 4 He below 250 mK". Phys. Rev. Lett. 97 (16) 165301. arXiv:cond-mat/0604528. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..97p5301R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.165301. PMID 17155406. S2CID 45453420.

- ^ Sophie, A; Rittner C (2007). "Disorder and the Supersolid State of Solid 4 He". Phys. Rev. Lett. 98 (17) 175302. arXiv:cond-mat/0702665. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98q5302R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.175302. S2CID 119469548.

- ^ Boninsegni, M; Prokofev (2006). "Superglass Phase of 4 He". Phys. Rev. Lett. 96 (13) 135301. arXiv:cond-mat/0603003. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..96m5301W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.135301. PMID 16711998. S2CID 41657202.

- ^ Pollet, L; Boninsegni M (2007). "Superfuididty of Grain Boundaries in Solid 4 He". Phys. Rev. Lett. 98 (13) 135301. arXiv:cond-mat/0702159. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98m5301P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.135301. PMID 17501209. S2CID 20038102.

- ^ Tanaeva, I. A. (2004). "Superfluid Vortex Cooler". AIP Conference Proceedings (PDF). Vol. 710. pp. 034911–1/8. doi:10.1063/1.1774894. S2CID 109758743.

- ^ Ohba, Tomonori (2016). "Limited Quantum Helium Transportation through Nano-channels by Quantum Fluctuation". Scientific Reports. 6 28992. Bibcode:2016NatSR...628992O. doi:10.1038/srep28992. PMC 4929499. PMID 27363671.

- ^ Swenson, C. (1950). "The Liquid-Solid Transformation in Helium near Absolute Zero". Physical Review. 79 (4): 626. Bibcode:1950PhRv...79..626S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.79.626.

- ^ Keesom, W.H.; Keesom, A.P. (1935). "New measurements on the specific heat of liquid helium". Physica. 2 (1): 557. Bibcode:1935Phy.....2..557K. doi:10.1016/S0031-8914(35)90128-8.

- ^ Buckingham, M.J.; Fairbank, W.M. (1961). "Chapter III The Nature of the λ-Transition in Liquid Helium". The nature of the λ-transition in liquid helium. Progress in Low Temperature Physics. Vol. 3. p. 80. doi:10.1016/S0079-6417(08)60134-1. ISBN 978-0-444-53309-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ E.L. Andronikashvili Zh. Éksp. Teor. Fiz, Vol.16 p.780 (1946), Vol.18 p. 424 (1948)

- ^ S. J. Putterman (1974), Superfluid Hydrodynamics (Amsterdam: North-Holland) ISBN 0-444-10681-2.

- ^ Landau, L. D. (1941), "The theory of superfluidity of helium II", Journal of Physics, Vol. 5, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, p. 71.

- ^ Khalatnikov, I. M. (1965), An introduction to the theory of superfluidity (New York: W. A. Benjamin), ISBN 0-7382-0300-9.

- ^ Van Alphen, W. M.; Van Haasteren, G. J.; De Bruyn Ouboter, R.; Taconis, K. W. (1966). "The dependence of the critical velocity of the superfluid on channel diameter and film thickness". Physics Letters. 20 (5): 474. Bibcode:1966PhL....20..474V. doi:10.1016/0031-9163(66)90958-9.

- ^ De Waele, A. Th. A. M.; Kuerten, J. G. M. (1992). "Chapter 3: Thermodynamics and Hydrodynamics of 3He–4He Mixtures". Thermodynamics and hydrodynamics of 3He–4He mixtures. Progress in Low Temperature Physics. Vol. 13. p. 167. doi:10.1016/S0079-6417(08)60052-9. ISBN 978-0-444-89109-9.

- ^ Staas, F. A.; Severijns, A. P.; Van Der Waerden, H. C.bM. (1975). "A dilution refrigerator with superfluid injection". Physics Letters A. 53 (4): 327. Bibcode:1975PhLA...53..327S. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(75)90087-0.

- ^ Castelijns, C.; Kuerten, J.; De Waele, A.; Gijsman, H. (1985). "3He flow in dilute 3He-4He mixtures at temperatures between 10 and 150 mK". Physical Review B. 32 (5): 2870–2886. Bibcode:1985PhRvB..32.2870C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.32.2870. PMID 9937394.

- ^ Zeegers, J. C. H. Critical velocities and mutual friction in 3He-4He mixtures at low temperatures below 100 mK, thesis, Appendix A, Eindhoven University of Technology, 1991.

- ^ Alonso, J. L.; Ares, F.; Brun, J. L. (October 5, 2018). "Unraveling the Landau's consistence criterion and the meaning of interpenetration in the "Two-Fluid" Model". The European Physical Journal B. 91 (10): 226. arXiv:1806.11034. Bibcode:2018EPJB...91..226A. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2018-90105-x. ISSN 1434-6028. S2CID 53464405.

- ^ F. London (1938). "The λ-Phenomenon of Liquid Helium and the Bose-Einstein Degeneracy". Nature. 141 (3571): 643–644. Bibcode:1938Natur.141..643L. doi:10.1038/141643a0. S2CID 4143290.

- ^ L. Tisza (1938). "Transport Phenomena in Helium II". Nature. 141 (3577): 913. Bibcode:1938Natur.141..913T. doi:10.1038/141913a0. S2CID 4116542.

- ^ L. Tisza (1947). "The Theory of Liquid Helium". Phys. Rev. 72 (9): 838–854. Bibcode:1947PhRv...72..838T. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.72.838.

- ^ Bijl, A; de Boer, J; Michels, A (1941). "Properties of liquid helium II". Physica. 8 (7): 655–675. Bibcode:1941Phy.....8..655B. doi:10.1016/S0031-8914(41)90422-6.

- ^ Braun, L. M., ed. (2000). Selected papers of Richard Feynman with commentary. World Scientific Series in 20th century Physics. Vol. 27. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-4131-5. Section IV (pages 313 to 414) deals with liquid helium.

- ^ R. P. Feynman (1954). "Atomic Theory of the Two-Fluid Model of Liquid Helium" (PDF). Phys. Rev. 94 (2): 262. Bibcode:1954PhRv...94..262F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.94.262.

- ^ R. P. Feynman & M. Cohen (1956). "Energy Spectrum of the Excitations in Liquid Helium" (PDF). Phys. Rev. 102 (5): 1189–1204. Bibcode:1956PhRv..102.1189F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.102.1189.

- ^ T. D. Lee; K. Huang & C. N. Yang (1957). "Eigenvalues and Eigenfunctions of a Bose System of Hard Spheres and Its Low-Temperature Properties". Phys. Rev. 106 (6): 1135–1145. Bibcode:1957PhRv..106.1135L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.106.1135.

- ^ L. Liu; L. S. Liu & K. W. Wong (1964). "Hard-Sphere Approach to the Excitation Spectrum in Liquid Helium II". Phys. Rev. 135 (5A): A1166 – A1172. Bibcode:1964PhRv..135.1166L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.135.A1166.

- ^ A. P. Ivashin & Y. M. Poluektov (2011). "Short-wave excitations in non-local Gross-Pitaevskii model". Cent. Eur. J. Phys. 9 (3): 857–864. arXiv:1004.0442. Bibcode:2011CEJPh...9..857I. doi:10.2478/s11534-010-0124-7. S2CID 118633189.

- ^ Santos, L.; Shlyapnikov, G. V.; Lewenstein, M. (2003). "Roton-Maxon Spectrum and Stability of Trapped Dipolar Bose-Einstein Condensates". Physical Review Letters. 90 (25) 250403. arXiv:cond-mat/0301474. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90y0403S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.250403. PMID 12857119. S2CID 25309672.

- ^ K. G. Zloshchastiev (2012). "Volume element structure and roton-maxon-phonon excitations in superfluid helium beyond the Gross-Pitaevskii approximation". Eur. Phys. J. B. 85 (8) 273. arXiv:1204.4652. Bibcode:2012EPJB...85..273Z. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2012-30344-3. S2CID 118545094.

- ^ A. V. Avdeenkov & K. G. Zloshchastiev (2011). "Quantum Bose liquids with logarithmic nonlinearity: Self-sustainability and emergence of spatial extent". J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 44 (19) 195303. arXiv:1108.0847. Bibcode:2011JPhB...44s5303A. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/44/19/195303. S2CID 119248001.

- ^ Hugh Everett, III. The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics: the theory of the universal wave function. Everett's Dissertation

- ^ I.I. Hirschman, Jr., A note on entropy. American Journal of Mathematics (1957) pp. 152–156

Further reading

[edit]- Antony M. Guénault: Basic superfluids. Taylor & Francis, London 2003, ISBN 0-7484-0891-6

- D.R. Tilley and J. Tilley, Superfluidity and Superconductivity, (IOP Publishing Ltd., Bristol, 1990)

- Department of Energy Office of Science: Superfluidity

- Hagen Kleinert, Gauge Fields in Condensed Matter, Vol. I, "SUPERFLOW AND VORTEX LINES", pp. 1–742, World Scientific (Singapore, 1989); Paperback ISBN 9971-5-0210-0 (also available online Archived May 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine)

- James F. Annett: Superconductivity, superfluids, and condensates. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford 2005, ISBN 978-0-19-850756-7

- Leggett, A. (1999). "Superfluidity". Reviews of Modern Physics. 71 (2): S318 – S323. Bibcode:1999RvMPS..71..318L. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.71.S318.

- London, F. Superfluids (Wiley, New York, 1950)

- Philippe Lebrun & Laurent Tavian: The technology of superfluid helium

External links

[edit]- Helium-4 Interactive Properties

- http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2005/matter.html

- Liquid Helium II, Superfluid: demonstrations of Lambda point transition/viscosity paradox /two fluid model/fountain effect/creeping film/ second sound.

- Physics Today February 2001

- Rousseau, V. G. (2014). "Superfluid density in continuous and discrete spaces: Avoiding misconceptions". Physical Review B. 90 (13) 134503. arXiv:1403.5472. Bibcode:2014PhRvB..90m4503R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.90.134503. S2CID 118518974.

- superfluid hydrodynamics Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Superfluid phases of helium

- The Hindu article on superfluid states

- Video including superfluid helium's strange behavior

Superfluid helium-4

View on GrokipediaDiscovery and History

Early Experiments and Discovery

In 1927, W. H. Keesom and M. Wolfke at Leiden University conducted calorimetric measurements on liquid helium-4 and observed a sharp anomaly in its specific heat, manifesting as a pronounced maximum at approximately 2.18 K.[11] This unexpected feature indicated a phase transition, later termed the λ-transition due to the Greek letter's resemblance to the curve's shape, though its physical origin remained unexplained at the time.[1] Early data placed the transition temperature near 2.17 K under saturated vapor pressure conditions.[11] Subsequent refinements in the late 1920s and early 1930s confirmed the transition at a more precise value of 2.172 K, with no associated latent heat, distinguishing it from typical first-order phase changes.[1] Keesom designated the high-temperature phase above this λ-point as helium-I (He-I), exhibiting normal liquid behavior, and the low-temperature phase below it as helium-II (He-II).[1] These phases highlighted intriguing thermal anomalies, including unusually high thermal conductivity in He-II, but the full implications awaited further hydrodynamic studies.[11] The defining property of superfluidity in helium-4 emerged from viscosity measurements in 1937–1938. Independently, Pyotr Kapitza in Moscow and John F. Allen and Don Misener in Cambridge demonstrated that He-II flows through narrow channels with negligible resistance, implying zero viscosity below the λ-point.[1] Kapitza's setup involved forcing liquid helium through a capillary tube of about 0.2 mm diameter, where the flow rate increased dramatically below 2.17 K without proportional pressure drop, suggesting frictionless motion. Similarly, Allen and Misener used fine glass capillaries to observe persistent flow rates exceeding normal fluid limits by orders of magnitude in He-II, confirming the superfluid nature. These experiments, published concurrently in January 1938, marked the empirical discovery of superfluidity as a macroscopic quantum phenomenon.[1]Key Milestones and Theoretical Developments

In 1938, J. F. Allen and H. Jones observed the fountain effect in superfluid helium-4, where a temperature difference across a narrow capillary connecting two reservoirs causes helium to flow from the colder to the warmer side against a pressure gradient, demonstrating the thermomechanical coupling inherent to superfluidity. This phenomenon provided early experimental evidence of the distinct transport properties below the lambda point, with the pressure difference ΔP related to the temperature difference ΔT by ΔP = ρ S ΔT, where ρ is the total density and S the entropy per unit mass. Concurrently in 1938, Fritz London proposed that superfluidity arises from Bose-Einstein condensation of helium-4 atoms, offering a quantum mechanical interpretation.[1] During the late 1930s and 1940s, experiments by Bernard V. Rollin and others revealed the formation of thin superfluid films that creep along surfaces, known as Rollin films, with a typical thickness of approximately 100 nm and flow speeds around 20 cm/s, illustrating the zero-viscosity flow even in confined geometries.[12] These observations confirmed the superfluid's ability to transfer mass without resistance over solid boundaries, a key manifestation of its macroscopic quantum behavior, and were quantified through measurements of film transfer rates under gravitational potentials.[13] In 1938, László Tisza proposed the two-fluid model, which Lev Landau refined in 1941 by introducing a microscopic interpretation based on elementary excitations, positing that superfluid helium-4 below the lambda temperature consists of an inviscid superfluid component with density ρ_s and a viscous normal fluid component with density ρ_n, where the total density ρ = ρ_s + ρ_n, explaining phenomena like the temperature-dependent viscosity and heat transport.[14] This phenomenological framework successfully accounted for the observed fountain effect and film flow by treating the superfluid as carrying no entropy while the normal fluid behaves like a classical gas of excitations, and it predicted the existence of second sound as a temperature wave.[14] In 1955, Richard Feynman proposed the concept of quantized vortices to describe rotational motion in superfluid helium-4, arguing that circulation around a vortex line must be quantized in units of , where is Planck's constant and is the mass of a helium-4 atom, leading to stable, singly quantized vortex cores with a healing length on the order of angstroms.[15] This theoretical insight explained the irrotational nature of superfluid flow and the formation of vortex tangles in rotating containers, later confirmed experimentally through observations of vortex arrays.[15] The 1996 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to David M. Lee, Douglas D. Osheroff, and Robert C. Richardson for their discovery of superfluidity in helium-3 at millikelvin temperatures, building on the foundational understanding of helium-4 superfluidity that informed their low-temperature techniques and highlighted the broader quantum fluid paradigm.[16]Recent Advances (Post-2000)

In 2004, physicists Eun-Seong Kim and Moses H. W. Chan reported experimental evidence for a supersolid phase in solid helium-4 using torsional oscillator measurements, where a portion of the solid appeared to decouple and flow without viscosity below 200 mK. This announcement sparked intense interest, as it suggested a novel quantum state combining solid order with superfluidity. However, subsequent experiments in the 2010s, including refined torsional oscillator studies by Chan's own group, attributed the original signals to elastic anomalies and disorder in the solid rather than true supersolidity, though related phenomena like non-classical rotational inertia persisted in impure samples. Advances in visualizing vortex dynamics emerged in the mid-2000s and evolved through the 2020s, enabling direct observation of quantized vortices in superfluid helium-4. In 2006, researchers introduced a technique using micron-sized solid hydrogen particles as tracers, illuminated by lasers to image vortex cores in three dimensions and reveal their reconnection during quantum turbulence. This approach was refined in the 2010s and 2020s with fluorescent nanoparticles, such as semiconductor quantum dots dispersed in the superfluid, which scatter light to track vortex motion at high resolution without significantly perturbing the flow, thus providing unprecedented insights into turbulent vortex tangles.[17] Measurement techniques for superfluid flows also advanced significantly in the 2010s and 2020s through molecular tagging velocimetry (MTV), which labels helium molecules with laser-induced excitations and tracks their displacement to map velocity fields. This non-intrusive method, adapted for cryogenic conditions, has quantified counterflow velocities and normal fluid components in helium-4 pipes, overcoming challenges like low signal-to-noise ratios in dilute excitations.[18] Theoretical modeling progressed with the development of geometric one-fluid formulations in 2025, deriving Hamiltonian-based equations for superfluid helium-4 that unify mass density and clebsch potentials in a single framework, facilitating simulations of quantum turbulence without explicit two-fluid separation.[19] Recent experimental breakthroughs from 2020 to 2025 include the magnetic levitation of millimeter-scale superfluid helium-4 drops in high vacuum at 330 mK, where the drops maintain coherence and exhibit optical whispering gallery modes, opening avenues for studying isolated quantum hydrodynamics.[20] In 2020, ultrafast reactions in superfluid helium nanodroplets were probed using extreme ultraviolet (XUV) laser pulses, revealing femtosecond-scale bubble formation and energy dissipation triggered by resonant excitations.[21] That same year, a universal law governing quantum vortex dynamics was identified, showing that reconnecting vortices in superfluid helium separate at speeds exceeding their approach velocities, a principle derived from high-fidelity simulations applicable to broader quantum fluid systems.[22]Physical Properties

Basic Characteristics and Phase Transition

Superfluid helium-4, denoted as ^4He, consists of bosonic atoms with zero spin, enabling the formation of a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) below the lambda point temperature T_λ = 2.1768 K at saturated vapor pressure.[23][24] This phase transition marks the onset of superfluidity, where the liquid helium, known as He-II, exhibits quantum mechanical behavior on a macroscopic scale, contrasting with the normal fluid phase He-I above T_λ. The BEC arises as a significant fraction of the atoms occupy the ground state, leading to coherent quantum effects that underpin the superfluid properties.[25] In the superfluid phase (He-II), the fluid demonstrates zero viscosity (η_s = 0), allowing it to flow without energy dissipation through narrow channels, as first observed in capillary experiments. Additionally, He-II possesses effectively infinite thermal conductivity (κ → ∞), enabling rapid heat transport without temperature gradients via counterflow of normal and superfluid components, a stark difference from the finite conductivity in He-I. These properties highlight the dissipationless nature of the superfluid state, where entropy is carried exclusively by the normal fluid component. The lambda transition is characterized by a sharp anomaly in the specific heat, which diverges logarithmically near T_λ, well-described by the power-law form C ~ |T - T_λ|^α with the critical exponent α ≈ -0.0127, as determined from high-precision measurements and confirmed by renormalization group theory for the 3D XY universality class. Near the transition, the superfluid density ρ_s(T) emerges and vanishes as ρ_s(T) ∝ (T_λ - T)^{2/3}, reflecting the critical slowing down of order parameter fluctuations.[26] The isotope effect explains why superfluidity in ^4He occurs at significantly higher temperatures than in ^3He, primarily due to the bosonic statistics of ^4He allowing direct BEC, whereas the lighter mass and fermionic nature of ^3He require Cooper pairing at millikelvin temperatures, with the mass difference influencing the de Broglie wavelength and effective interaction scales.[27] This distinction underscores the role of quantum statistics in determining the phase diagram of helium isotopes.Film Flow and Creeping

In superfluid helium-4, a thin layer known as the Rollin film forms on solid surfaces, typically with a thickness of 10-30 nm, enabling frictionless flow along walls without viscous drag.[28] This phenomenon was first described by Bernard V. Rollin in 1936, who observed the film creeping over container edges, such as in siphoning experiments where liquid helium-4 flows uphill against gravity from a beaker.[29] The film's superfluid component moves via potential flow driven by chemical potential gradients, achieving creeping speeds up to 20 cm/s while exhibiting no Poiseuille-type dissipation characteristic of normal fluids.[30] The flow in these films remains dissipationless until reaching a critical velocity of approximately 10-20 cm/s, beyond which superfluidity breaks down due to the nucleation of quantized vortices at surface edges or irregularities.[31] Vortex formation dissipates energy through the creation of excitations, limiting the sustainable flow rate and leading to a transition to normal fluid behavior. This critical velocity scales with film thickness and temperature, decreasing as the layer thins or warms, consistent with observations in narrow capillaries and surface coatings.[32] Experimental studies of Rollin films have extended to investigations of supersolid phases, where thin helium-4 layers adsorbed on substrates like graphite exhibit both spatial order and superfluid flow, providing a platform to probe quantum phases beyond bulk superfluidity.[33] These films maintain superfluid properties below the bulk λ-transition temperature of 2.17 K, with flow persistence observed in setups mimicking early 1930s demonstrations but refined for modern precision measurements.[34]Rotation and Quantized Vortices

When a superfluid helium-4 sample is subjected to rotation, the superfluid component cannot mimic classical rigid-body rotation due to its irrotational nature, instead developing an array of discrete quantized vortices to accommodate the imposed angular momentum. The circulation of the superfluid velocity around any closed path enclosing a vortex is quantized according to , where is an integer, m²/s is the quantum of circulation ( is Planck's constant and is the mass of a helium-4 atom), first predicted independently by Onsager in 1949 and Feynman in 1955.[35][36] This quantization arises from the single-valuedness of the superfluid wavefunction, leading to singly charged () vortex lines as the stable configuration, with higher windings unstable. Each vortex line features a hollow core where the superfluid density vanishes, with a diameter on the order of 1 Å, set by the healing length m near , over which the order parameter recovers its bulk value.[37][38] In a rotating container, such as a cylindrical bucket spun at angular velocity , these vortex lines arrange into a regular lattice to minimize energy, analogous to the Abrikosov vortex lattice in type-II superconductors. The equilibrium vortex density follows the Feynman-Onsager relation , ensuring the average superfluid vorticity matches , with the lattice typically forming a triangular (Abrikosov) structure for uniform rotation.[39] This configuration has been directly visualized in experiments using tracer particles or optical methods, confirming the predicted density and hexagonal ordering for rotation rates up to several rad/s.[39][40] Isolated quantized vortices can also manifest as rings, observed in superfluid helium-4 through techniques like particle imaging or ion trapping, where they propagate via self-induction at speeds on the order of 1 cm/s, depending on ring radius and temperature.[41] These vortex rings expand or contract under mutual interactions but maintain quantized circulation, providing a basic unit for understanding more complex vortex dynamics, including their role in initiating quantum turbulence.[41]Quantum Turbulence

Quantum turbulence in superfluid helium-4 refers to a disordered, tangle-like configuration of quantized vortex lines that arises in the superfluid component under conditions of high relative velocity between the superfluid and normal fluid components, or through mechanical agitation, leading to chaotic reconnection dynamics.[42] The mean intervortex spacing in this tangle is characterized by , where is the quantum of circulation ( is Planck's constant and the helium-4 mass) and the energy dissipation rate per unit mass.[42] This state is distinct from ordered vortex arrays and manifests primarily at temperatures below the lambda point, with negligible normal fluid influence below K.[43] Quantum turbulence is generated experimentally through methods such as towing a grid through stationary superfluid helium-4 or inducing thermal counterflow in narrow channels, where the relative velocity exceeds a critical threshold, producing a dense vortex tangle.[44] These techniques, pioneered in the mid-20th century, allow controlled studies of tangle evolution, with counterflow being particularly effective for achieving steady-state turbulence at low temperatures. Observations confirm that such tangles form rapidly and persist until dissipation mechanisms dominate.[42] The temporal evolution of the vortex line density (total length of vortex lines per unit volume) in quantum turbulence is described by the phenomenological Vinen equation: where is the superfluid velocity relative to the normal fluid, and , , are temperature-dependent coefficients accounting for vortex growth, decay, and reconnection processes, respectively. This equation, originally derived from mutual friction considerations in counterflow, captures the balance between production and annihilation of vortex length, leading to stationary states where .[44] Extensions of this model incorporate finite-temperature effects but retain its core form for low-temperature regimes.[42] At large scales, quantum turbulence exhibits intermittency and scaling behaviors analogous to classical turbulence, with the energy spectrum following a Kolmogorov-like form for wavenumbers corresponding to lengths much larger than the intervortex spacing.[44] This quasiclassical regime arises from the collective motion of many quantized vortices, mimicking continuous vorticity distributions.[42] At small scales, below , quantum effects impose a cutoff, transitioning to phonon-dominated dissipation without the viscous cascade of classical fluids.[43] Visualization of quantum turbulence has advanced significantly, particularly in the 2020s, using particle tracking velocimetry (PTV) with micron-sized solid hydrogen or deuterium tracers that adhere to vortex lines, enabling direct imaging of tangle dynamics via high-speed cameras.[45] Complementary techniques include second sound attenuation, where temperature oscillations probe vortex-induced damping, providing quantitative maps of with sub-millimeter resolution in counterflow setups.[42] These methods have revealed reconnection events and large-scale flow structures, confirming the hybrid classical-quantum nature of the turbulence.[45]Confinement Effects

Confinement of superfluid helium-4 in nanoscale pores, channels, or planar geometries significantly modifies its quantum properties due to enhanced boundary effects and finite-size scaling. In porous media such as silica gels or MCM-41 with pore diameters below 100 nm, the superfluid transition temperature is suppressed compared to the bulk value of 2.17 K, primarily because boundary conditions restrict phase coherence and correlation lengths.[46] This suppression becomes pronounced in narrower pores, where the transition can shift continuously toward lower temperatures or even approach zero in highly restricted one-dimensional (1D) geometries. The superfluid density in these confined systems follows finite-size scaling behavior, expressed as , where is the confinement length (e.g., pore diameter) and .[46] This scaling arises from the divergence of the correlation length being cut off by the finite geometry, leading to reduced superfluid fraction near the transition; experimental measurements in aerogels and Vycor pores confirm this form, though deviations occur in strong 3D-to-2D crossovers due to connectivity effects.[46] In disordered porous media like aerogels, the roton spectrum of helium-4 excitations undergoes notable shifts, with the minimum energy increasing relative to the bulk value of approximately 8.6 K. This hardening of the roton gap, observed via inelastic neutron scattering, results from scattering off the porous matrix, which broadens and raises the dispersion minimum by about 0.5 K in typical silica aerogels at low filling fractions. In contrast, two-dimensional (2D) confinement, such as in thin films or slit-like channels, leads to gapless phonon-like modes dominating the low-energy spectrum, as the roton minimum is absent in strict 2D superfluids.[47] Planar geometries induce a dimensional crossover from 3D to 2D superfluidity as the layer thickness decreases below roughly 10 atomic layers, replacing the bulk -transition with a lower-temperature Kosterlitz-Thouless (KT) transition driven by vortex unbinding. Heat capacity and superfluid response measurements in confined films show this KT transition occurring around 0.3–0.5 K for thicknesses of 2–3 monolayers, with the superfluid stiffness jumping discontinuously at . Recent experiments in the 2020s have explored extreme confinements, such as helium-4 in carbon nanotubes, where enhanced zero-point energy in tubes with diameters below 7 Å prevents complete filling and quenches superfluid flow, with radial zero-point energies exceeding 80 K.[48] In argon-plated MCM-41 pores (effective diameter ~2 nm), pre-deposition of a single argon layer creates a quasi-1D core liquid exhibiting Luttinger liquid behavior with a superfluid transition suppressed above 4 K and fermion-like correlations (Luttinger parameter ).[49] These setups reveal persistent 1D quantum hydrodynamics, with linear dispersion persisting to higher temperatures than in bulk.Comparison with Helium-3

Superfluid helium-4 (^4He) and superfluid helium-3 (^3He) exhibit fundamentally different behaviors due to the quantum statistics of their constituent atoms: ^4He atoms are composite bosons with total spin 0, enabling direct Bose-Einstein condensation, whereas ^3He atoms are fermions with spin 1/2, requiring the formation of Cooper pairs to achieve superfluidity.[16] This distinction arises from the even number of fermions (protons and neutrons) in ^4He nuclei versus the odd number in ^3He, leading to bosonic and fermionic statistics, respectively.[50] The superfluid transition in ^4He occurs at the lambda point of approximately 2.17 K via Bose-Einstein condensation of the bosonic atoms into a single quantum state, akin to an s-wave symmetric ground state without pairing.[16] In contrast, ^3He achieves superfluidity only at much lower temperatures, around 2.5 mK (depending on pressure), through p-wave pairing of fermionic atoms into bosonic Cooper pairs, analogous to BCS superconductivity but with anisotropic orbital momentum.[16] The vastly lower transition temperature for ^3He reflects the Pauli exclusion principle, which prevents direct condensation and necessitates thermal energies below the pairing energy scale (~k_B T_c ~ 10^{-7} eV) to form pairs.[16] At absolute zero, the superfluid density fraction ρ_s/ρ approaches 1 in both isotopes, indicating a fully superfluid state with no normal fluid component. However, the temperature dependence differs markedly: in ^4He, thermal depopulation of bosonic excitations leads to a gradual decrease in ρ_s/ρ, while in ^3He, the fermionic nature results in a normal fluid dominated by gapped quasiparticles from the Fermi surface, yielding a lower ρ_s/ρ at comparable reduced temperatures (T/T_c) due to the higher density of states near the Fermi level.[51] The elementary excitations also highlight key contrasts: ^4He features a spectrum of gapless phonons at low momentum and gapped rotons at higher momentum (~8 K energy minimum), contributing to the normal fluid via thermal activation.[52] In ^3He, excitations include collective modes like phonons and pair-breaking continuum from Cooper pair disruption, but lack rotons; the normal fluid arises from fermionic quasiparticles with an anisotropic p-wave gap (~Δ ~ 1-2 K). Notably, ^3He superfluids exhibit no lambda anomaly—a sharp specific heat divergence at T_c characteristic of ^4He—owing to the smoother second-order transition without the same critical fluctuations in the bosonic order parameter.[51] Critical velocities, beyond which superflow becomes dissipative, are generally higher in ^4He (~10 m/s in fine capillaries, limited by roton creation or vortex nucleation) than in ^3He (~0.1-1 m/s, often set by pair-breaking).[32][53] This difference stems from the healing length ξ, the scale over which the superfluid order parameter varies: ξ ≈ 0.2 nm in ^4He (small due to high T_c and tight binding), versus ξ ≈ 100-500 nm in ^3He (larger owing to weak pairing at low T_c), yielding v_c ∝ ħ/(m ξ) larger for ^4He despite similar atomic masses.[32] In dilute ^3He-^4He mixtures, ^3He atoms act as fermionic impurities that dilute ^4He superfluidity by scattering bosonic excitations and depressing the lambda transition temperature (e.g., T_λ drops by ~0.1 K for 5% ^3He concentration).[54] At low temperatures (<0.3 K), phase separation occurs into a ^3He-rich normal phase and ^4He-rich superfluid phase, enabling applications like dilution refrigeration where ^3He circulation across the interface provides cooling.[54][55] The effective interaction between ^3He quasiparticles in the ^4He matrix further modifies transport, reducing the superfluid fraction proportionally to ^3He concentration until full suppression at ~6-7%.[54][56]Applications

Cryogenic Cooling and Heat Transport

Superfluid helium-4 plays a crucial role in dilution refrigerators, which achieve temperatures as low as 10 mK by exploiting the phase separation of 3He-4He mixtures below approximately 0.8 K. In these systems, the mixture separates into a concentrated phase rich in 3He and a dilute phase where 3He atoms dissolve into the superfluid 4He background, enabling continuous cooling through the endothermic process of dilution as 3He evaporates from the concentrated phase and reabsorbs into the dilute phase.[55] This phase separation leverages the immiscibility of the isotopes at low temperatures, allowing efficient heat extraction without mechanical moving parts, and has been refined in modern designs for continuous operation at sub-kelvin levels. Superfluid helium-4 cryostats are essential for maintaining temperatures around 1.9 K in large-scale particle physics experiments, such as the superconducting magnets in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. These cryostats use pressurized superfluid 4He to provide high thermal stability and efficient cooling over extended volumes, with the fluid's zero viscosity enabling uniform temperature distribution across complex magnet structures spanning kilometers.[57] The LHC's cryogenic system, for instance, circulates approximately 120 tonnes of superfluid helium to cool 1232 dipole magnets, demonstrating the scalability of this technology for high-field superconductivity applications.[58] A key limitation in heat transport involving superfluid helium-4 is the Kapitza resistance at solid-helium interfaces, where the thermal boundary conductance h follows (with ) for low heat fluxes and temperatures below 2 K, arising from acoustic mismatch between phonons in the solid and the helium's excitation spectrum. This resistance, first quantified in experiments with copper and other metals, results in a temperature jump proportional to the heat flux divided by , constraining the maximum heat transfer rates in cryogenic designs.[59] Despite this, superfluid helium's bulk thermal conductivity remains exceptionally high, allowing effective overall cooling when interface effects are minimized through surface treatments or thin films.[60] For pulsed-load cooling scenarios, such as transient heat dissipation in detectors or space-based systems, the fountain effect in superfluid helium-4 enables rapid, non-mechanical heat removal by generating thermomechanical pressure gradients that drive fluid flow. In fountain pumps, localized heating creates an osmotic pressure difference, propelling superfluid helium through porous media or channels to absorb and transport heat pulses away from sensitive components, as demonstrated in NASA transfer systems where it handles variable thermal loads during helium relocation.[61] This approach provides millisecond response times, ideal for intermittent high-heat events in superconducting devices. Advances in the 2020s have introduced superfluid vortex coolers, which combine fountain pumping with vortex-induced counterflow to achieve temperatures down to 1.19 K without mechanical components, by integrating with pulse-tube refrigerators for enhanced efficiency. These devices exploit the quantized vortices in rotating superfluid helium to facilitate heat rejection at higher temperatures while maintaining low base cooling, offering compact alternatives for precision cryogenic applications.Precision Instrumentation and Sensors

Superfluid helium-4's zero viscosity and quantized circulation enable its use in high-precision gyroscopes that detect rotation through the precession of quantized vortices. In these devices, a persistent current of superfluid around a central vortex responds to angular velocity, producing a measurable phase shift or frequency change proportional to the rotation rate. For instance, SQUID-based superfluid gyroscopes, analogous to superconducting quantum interference devices, exploit the interference of superfluid flow paths to achieve high sensitivities surpassing classical mechanical gyroscopes in low-temperature environments. In 2025, superfluid helium gyrometers demonstrated 0.2% quantum accuracy in resolving frame-dragging, advancing tests of general relativity.[62] These instruments leverage the macroscopic quantum coherence of helium-4, where quantized vortices—circulation quanta of h/m (with h Planck's constant and m the helium-4 mass)—precess under rotation, allowing absolute rotation sensing without mechanical wear. Accelerometers utilizing superfluid helium-4 capitalize on gradients in the fountain pressure, which arises from differences in chemical potential across a temperature or concentration gradient in the two-fluid model. Under acceleration, an effective gravitational field induces a counterflow between the superfluid and normal components, altering the fountain pressure and enabling detection of linear accelerations. This principle has been demonstrated in prototype devices where superfluid flow through porous membranes or films responds to inertial forces, providing a basis for compact, vibration-insensitive sensors in cryogenic applications. The absence of viscosity ensures rapid response times, on the order of milliseconds, making these accelerometers suitable for precision navigation in space or geophysical monitoring. Superfluid helium droplet spectroscopy (SHeDS) employs beams of helium-4 nanodroplets to isolate and study molecular clusters at ultralow temperatures of approximately 0.37 K, achieved through evaporative cooling in vacuum. These droplets, typically 10^3 to 10^6 atoms in size, act as gentle, superfluid matrices that minimally perturb embedded molecules, allowing high-resolution infrared and UV spectroscopy of weakly bound complexes without thermal broadening. This technique has revealed detailed structures of biomolecules and van der Waals clusters, such as the rotational constants of water dimers, by exploiting the droplets' superfluidity to facilitate rapid energy dissipation and maintain isolation. Seminal experiments using SHeDS have advanced understanding of solvation dynamics and quantum state preparation in cold chemistry.[63] Quantum sensors for gravitational waves based on helium-4 thin films detect minute strains through the propagation of third sound—ripples on the film surface that couple to spacetime perturbations. These films, adsorbed on substrates at thicknesses of 10-100 nm, exhibit superfluid behavior below 1.2 K, with third sound velocities around 200 m/s enabling interferometric detection of wave-induced phase shifts. Proposals involve large-area film resonators monitored by optical or capacitive readout, potentially achieving strain sensitivities of 10^{-20}/√Hz in the 1-100 Hz band, targeting continuous waves from pulsars. Recent optomechanical configurations integrate these films with optical cavities, where gravitational wave-induced displacements modulate the cavity resonance via the film's areal density changes. In 2023, advances in levitated superfluid helium-4 drops demonstrated contactless manipulation via magnetic or optical trapping in high vacuum, preserving the drops' integrity for extended periods due to their low evaporation rates below 10^{-5} drops per second. Millimeter-scale drops, cooled to 330 mK, exhibit coherent quantum dynamics without container walls, enabling studies of shape oscillations and vortex formation under external fields. This technique exploits helium-4's superfluidity for frictionless motion, opening pathways for quantum sensing platforms isolated from environmental decoherence.[20]Fundamental Research Tools

Superfluid helium-4 serves as a versatile medium for fundamental research, enabling the isolation and study of quantum phenomena at low temperatures through techniques that leverage its unique superfluid properties. One prominent application is matrix isolation spectroscopy, where molecules or atoms are embedded in superfluid helium-4 nanodroplets, providing an ultracold, inert environment at approximately 0.37 K for high-resolution vibrational-rotational spectroscopy.[63] This method exploits the weak interactions between helium and solutes, allowing free rotation of small molecules like SF₆ and OCS, and enabling the stabilization of reactive species such as radicals (e.g., cyclopentadienyl C₅H₅) produced via pyrolysis.[63] The transparency of helium droplets across a broad spectral range—from microwaves to vacuum ultraviolet—facilitates studies of cluster structures, such as cyclic (H₂O)_n up to n=6, and even ionized species like aniline⁺, offering insights into solvation dynamics and quantum tunneling without the perturbations seen in traditional matrices.[63] Electron bubbles and ions in superfluid helium-4 act as sensitive probes for visualizing and tracking superfluid flow, particularly quantized vortices, due to their interactions with the Bernoulli-like force in the quantum fluid.[64] An excess electron forms a bubble of radius about 18.5 Å, while positive ions create snowball-like clusters; both exhibit temperature-dependent mobility influenced by scattering from phonons and rotons.[64] For instance, electron bubble mobility ranges from approximately 0.05 cm²/V·s at 2.1 K to nearly 1 cm²/V·s at 1.2 K, decreasing with rising temperature due to enhanced viscous drag, whereas positive ions show mobilities around 1.25 cm²/V·s at 1.15 K.[64][65] These particles have enabled the first experimental imaging of vortex lines by injecting ions and observing their trajectories under electric fields, providing direct evidence of superfluid hydrodynamics at the microscopic scale.[64] Rotating superfluid helium-4 experiments simulate the dynamics of neutron star interiors, particularly sudden spin-ups known as pulsar glitches, by mimicking the two-fluid model of a rigid crust coupled to an internal superfluid.[66] In these setups, a magnetically levitated vessel containing helium at ~1.5 K is spun at about 1 revolution per second and allowed to decelerate, with glitches manifesting as abrupt increases in rotational velocity due to vortex avalanches transferring angular momentum.[66] High-resolution measurements using LED-photodetector systems capture these events on millisecond timescales, replicating observations from pulsars like the Vela, and testing theories of superfluid-neutron coupling without the extreme densities of astrophysical objects.[66] Advances as of 2020 have utilized ultrafast extreme ultraviolet (XUV) laser pulses to probe non-equilibrium dynamics in superfluid helium-4, revealing rapid relaxation processes triggered by intense, femtosecond excitations.[67] These experiments, conducted with high-intensity XUV sources, induce transient states in helium droplets or bulk samples, allowing observation of ultrafast energy transfer to quasiparticles like rotons and subsequent helium evaporation or nanoplasma formation on picosecond scales.[67] Such techniques extend control over impurities and excitations, providing microscopic insights into breakdown of superfluidity under extreme conditions, as demonstrated in studies of laser-dressed helium responses.[67] Confinement of superfluid helium-4 in aerogels, porous silica structures with up to 98% porosity, tests universal critical phenomena near the lambda transition by introducing quenched disorder that alters scaling behavior.[68] Monte Carlo simulations using an XY model with fractal correlations show the superfluid density exponent ζ increasing from 0.67 in pure helium to 0.722 in aerogel, reflecting long-range disorder effects when the helium correlation length matches the aerogel's fractal scale.[68] This setup probes how randomness modifies the Bose-Einstein condensation and critical exponents, linking microscopic heterogeneity to macroscopic phase transitions, with parallels to confinement effects in other geometries.[68]Macroscopic Theory

Two-Fluid Model and Thermodynamics

The two-fluid model, first proposed by László Tisza in 1938 and developed hydrodynamically by Lev Landau in 1941, provides a phenomenological framework for understanding the macroscopic behavior of superfluid helium-4 (He II) below the lambda transition temperature K at saturated vapor pressure. In this model, liquid helium-4 is conceptualized as a composite of two interpenetrating, non-interacting fluid components: the inviscid superfluid with mass density and macroscopic velocity , and the viscous normal fluid with mass density and velocity . The total mass density of the liquid is conserved and given by , where is nearly independent of temperature in the superfluid phase. This decomposition accounts for the coexistence of frictionless flow (associated with ) and dissipative transport (associated with ) observed experimentally in He II.[14][12][7] Thermodynamically, the two-fluid model implies distinct roles for each component in carrying entropy and energy. The superfluid component has zero entropy per unit mass (), as it represents coherent motion without thermal disorder, while all entropy is borne by the normal component. The total entropy density is thus , where is the specific entropy of the normal fluid, analogous to that of a classical viscous fluid. This leads to key relations for thermodynamic potentials, such as the internal energy density , where and are the internal energies per unit mass of the respective components. The chemical potential and pressure are uniform across both components in equilibrium, ensuring mechanical balance. These relations highlight how thermal properties in He II arise primarily from excitations in the normal fluid, justifying the model's success in describing equilibrium thermodynamics without invoking microscopic details.[12][69] The densities and exhibit strong temperature dependence below . At low temperatures (), , reflecting near-complete superfluidity, while due to the phonon contribution to the normal fluid, as the momentum carried by long-wavelength phonons scales with in three dimensions. As temperature approaches from below, vanishes continuously ( at ), with the approach governed by critical exponents of the O(2) universality class. Microscopically, this behavior links to the spectrum of elementary excitations, such as phonons and rotons, which populate the normal component.[69][70] In the pressure-temperature (P-T) phase diagram of helium-4, the lambda line marks the boundary between the normal fluid phase (He I, above the line) and the superfluid phase (He II, below the line), originating near zero pressure at K and extending to higher pressures where decreases, terminating near the solid-liquid boundary at approximately 25 bar and 1.7 K. This line delineates a second-order phase transition, with no latent heat involved. At the lambda point, the specific heat at constant pressure exhibits a sharp discontinuity or near-logarithmic divergence, a hallmark of the O(2) (or 3D XY) universality class, where the critical exponent describes the weak singularity. This universality underscores the transition's connection to systems with continuous U(1) symmetry breaking, such as the onset of Bose-Einstein condensation in interacting bosons.[69][71]Superfluid Hydrodynamics

The macroscopic hydrodynamics of superfluid helium-4 is governed by the two-fluid model, which treats the system as a mixture of an inviscid superfluid component with density and velocity , and a viscous normal fluid component with density and velocity , where the total density is . This framework, originally proposed by Landau, captures the coupled dynamics of these interpenetrating fluids below the lambda transition temperature K.[14] The superfluid component obeys an Euler equation derived from the conservation of momentum in the absence of viscosity: where is the chemical potential per particle, is the mass of a helium-4 atom, and the flow is irrotational in the bulk () except at quantized vortex lines. This equation reflects the potential flow nature of the superfluid, with deviations from irrotationality confined to singular vortex structures.[14] The normal fluid follows a Navier-Stokes equation modified by interactions with the superfluid: where is the normal fluid viscosity, is a mutual friction coefficient, and is the normal fluid vorticity. The mutual friction term accounts for dissipative coupling between the components, arising from interactions with superfluid vortices. Mass conservation is expressed by the continuity equation: ensuring the total mass flux balances local density changes. Linearizing these equations around equilibrium yields propagating modes, including first sound as density waves with speed m/s at low temperatures, involving in-phase oscillations of and , and second sound as temperature or entropy waves with speed m/s, featuring out-of-phase counterflow of the components.[14][72] Superflow becomes unstable above a critical velocity , where is the minimum roton excitation energy ( K or J) and is the roton momentum ( with wavevector Å), leading to roton creation and breakdown of superfluidity; this Landau velocity is theoretically around 60 m/s but experimentally lower due to vortex nucleation.[14][73]Fountain Pressure and Related Phenomena

The fountain effect in superfluid helium-4, a hallmark thermomechanical phenomenon, occurs when a small temperature gradient across a porous plug or narrow capillary connecting two reservoirs induces a pressure difference that propels the superfluid component from the colder to the warmer region, counterintuitively climbing against gravity to form a fountain-like jet. This effect arises from the entropy imbalance between the reservoirs: the superfluid, carrying no entropy, flows to equalize the chemical potential while compensating for the entropy transport by the normal fluid. Predicted theoretically in the late 1930s, the effect was first observed experimentally in 1938 and demonstrates the irreversible nature of superfluid flow driven by thermodynamic forces rather than statistical pressure.[74] Within the two-fluid model, the pressure difference driving this flow is described by where and are the superfluid and total mass densities, is the entropy density carried primarily by the normal fluid, and is the temperature difference; at low temperatures where , this approximates to . This relation stems from the condition of constant chemical potential across the system, ensuring equilibrium in the absence of dissipative normal fluid flow through the restriction. Representative measurements at low temperatures yield bar for K, corresponding to an equivalent hydrostatic column height of about 56 m given helium's density of roughly 125 kg/m³.[74] The converse mechanocaloric effect manifests as cooling upon compression of the superfluid: applying pressure expels the entropy-bearing normal fluid through the connecting channel, reducing the entropy in the compressed volume and thereby lowering its temperature. This reversible process, measured down to temperatures around 0.4 K, highlights the intimate coupling between mechanical work and thermal properties in the two-fluid description, with temperature changes scaling proportionally to the applied pressure differential. Early experiments confirmed good agreement with thermodynamic predictions, showing cooling rates consistent with the entropy expulsion mechanism.[75] In setups with connected vessels, the fountain effect can trigger thermomechanical oscillations, where cyclic variations in temperature and pressure drive periodic superfluid inflow and outflow, often manifesting as sustained fountain jets reaching heights of approximately 10 cm. These oscillations arise from the feedback between heat-induced pressure buildup and the resulting fluid displacement, persisting until thermal equilibrium is approached.[76] When superfluid helium-4 flows through sufficiently narrow channels (on the order of micrometers), the velocity may exceed a critical value, leading to phase slippage: quantized vortices nucleate and traverse the channel, causing discrete 2π phase changes in the superfluid order parameter and resulting in periodic mass flow oscillations. This phenomenon, observed with frequencies scaling as the applied pressure gradient, serves as the superfluid analog of phase slips in one-dimensional superconductors and enables precise studies of vortex dynamics at finite temperatures.[77]Heat Transport Mechanisms

In superfluid helium-4, heat transport occurs through the counterflow of the normal and superfluid components, where the normal fluid carries the thermal energy away from the heat source while the superfluid component flows in the opposite direction to maintain zero net mass flux.[12] This mechanism results in an anomalously high effective thermal conductivity compared to classical fluids, as the superfluid experiences no viscosity and the normal fluid's motion is minimally dissipative at low velocities.[78] The relative velocity between the components in pure counterflow is given by , where is the heat flux vector, is the superfluid density, is the entropy per unit mass, and is the temperature; this relation derives from the two-fluid model's entropy conservation, with the superfluid carrying no entropy.[79] In the linear response regime, where mutual friction provides the primary dissipation, the effective thermal conductivity is , with the dimensionless mutual friction parameter and the normal fluid density.[12] The thermal conductivity reaches a peak of approximately W/m·K near 1 K, where is close to the total density and is small, maximizing the counterflow efficiency before higher heat fluxes induce turbulence or vortex formation that limits transport.[78] At higher temperatures closer to the lambda point (2.17 K), increasing reduces , while at lower temperatures, boundary effects and reduced entropy density further constrain it. This peak value underscores superfluid helium-4's utility in cryogenic applications, far exceeding that of normal helium or metals at similar temperatures. In narrow channels, heat transport mimics Poiseuille flow for the normal component, with the heat current proportional to (where is the temperature difference and the channel length) in the laminar regime, but a critical heat flux emerges when the superfluid velocity exceeds the Landau critical velocity, leading to vortex ring formation and transition to turbulent counterflow. The normal fluid's motion is driven by phonon wind at temperatures below ~0.6 K, where phonons dominate the entropy and create a drag-like effect on the superfluid, and by roton contributions above ~1 K, where rotons provide the majority of thermal excitation and enhance the counterflow velocity.[12] Near solid walls, heat transport is suppressed by boundary layers: the normal fluid adheres with a no-slip condition, forming a viscous layer that reduces effective flow, while the superfluid exhibits slip but is coupled via mutual friction, limiting overall conductivity in confined geometries by up to an order of magnitude compared to bulk values.[45]Microscopic Theory

Bose-Einstein Condensation and Ground State