Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

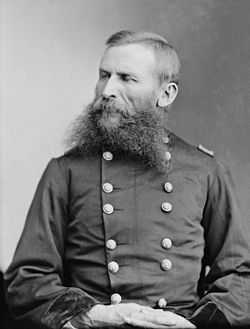

George Crook

View on Wikipedia

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890)[1][2][3] was a career United States Army officer who served in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. He is best known for commanding U.S. forces in the 1886 campaign that led to the defeat of the Apache leader Geronimo. As a result, the Apache nicknamed Crook Nantan Lupan, which means "Chief Wolf."[4]

Key Information

Early life and military career

[edit]Crook was born to Thomas and Elizabeth Matthews Crook on a farm near Taylorsville, Ohio. Nominated to the United States Military Academy by Congressman Robert Schenck, he graduated in 1852, ranking near the bottom of his class.

He was assigned to the 4th U.S. infantry as brevet second lieutenant, serving in California, 1852–61. He served in Oregon and northern California, alternately protecting or fighting against several Native American tribes. He commanded the Pitt River Expedition of 1857 and, in one of several engagements, was severely wounded by an Indian arrow. He established a fort in Northeast California that was later named in his honor; and later, Fort Ter-Waw in what is now Klamath Glen, California.[5]

During his years of service in California and Oregon, Crook extended his prowess in hunting and wilderness skills, often accompanying and learning from Indians whose languages he learned. These wilderness skills led one of his aides to liken him to Daniel Boone, and more importantly, provided a strong foundation for his abilities to understand, navigate and use Civil War landscapes to Union advantage.[5]

Crook was promoted to first lieutenant in 1856, and to captain in 1860. He was ordered east and in 1861, with the beginning of the American Civil War, was made colonel of the 36th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.[6]

He married Mary Tapscott Dailey of Virginia.

Civil War

[edit]Early service

[edit]

When the Civil War broke out, Crook accepted a commission as Colonel of the 36th Ohio Infantry and led it on duty in western Virginia. He was in command of the 3rd Brigade in the District of the Kanawha where he was wounded in a small fight at Lewisburg.[7] Crook returned to command his regiment during the Northern Virginia Campaign. He and his regiment were part of John Pope's headquarters escort at the Second Battle of Bull Run.

After the Union Army's defeat at Second Bull Run, Crook and his regiment were attached to the Kanawha Division at the start of the Maryland Campaign. On September 12 Crook's brigade commander, Augustus Moor, was captured and Crook assumed command of the 2nd Brigade, Kanawha Division which had been attached to the IX Corps. Crook led his brigade at the Battle of South Mountain and near Burnside's Bridge at the Battle of Antietam. He was promoted to the rank of brigadier general on September 7, 1862. During these early battles he developed a lifelong friendship with one of his subordinates, Col. Rutherford B. Hayes of the 23rd Ohio Infantry.

Following Antietam, General Crook assumed command of the Kanawha Division. His division was detached from the IX Corps for duty in the Department of the Ohio. Before long Crook was assigned to command an infantry brigade in the Army of the Cumberland. This brigade became the 3rd Brigade, 4th Division, XIV Corps, which he led at the Battle of Hoover's Gap. In July he assumed command of the 2nd Division, Cavalry Corps in the Army of the Cumberland. He fought at the Battle of Chickamauga and was in pursuit of Joseph Wheeler during the Chattanooga campaign.

In February 1864, Crook returned to command the Kanawha Division, which was now officially designated the 3rd Division of the Department of West Virginia.

Southwest Virginia

[edit]To open the spring campaign of 1864, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant ordered a Union advance on all fronts, minor as well as major. Grant sent for Brigadier General Crook, in winter quarters at Charleston, West Virginia, and ordered him to attack the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, Richmond's primary link to Knoxville and the southwest, and to destroy the Confederate salt works at Saltville, Virginia.

The 35-year-old Crook reported to army headquarters where the commanding general explained the mission in person. Grant instructed Crook to march his force, the Kanawha Division, against the railroad at Dublin, Virginia, 140 miles (230 km) south of Charleston. At Dublin he would put the railroad out of business and destroy Confederate military property. He was then to destroy the railroad bridge over New River, a few miles to the east. When these actions were accomplished, along with the destruction of the salt works, Crook was to march east and join forces with Major General Franz Sigel, who meanwhile was to be driving south up the Shenandoah Valley.

After long dreary months of garrison duty, the men were ready for action. Crook did not reveal the nature or objective of their mission, but everyone sensed that something important was brewing. "All things point to early action", the commander of the second brigade, Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, noted in his diary.

On April 29, 1864, the Kanawha Division marched out of Charleston and headed south. Crook sent a force under Brigadier General William W. Averell westward towards Saltville, then pushed on towards Dublin with nine infantry regiments, seven cavalry regiments, and 15 artillery pieces, a force of about 6,500 men organized into three brigades. The West Virginia countryside was beautiful that spring, but the mountainous terrain made the march a difficult undertaking. The way was narrow and steep, and spring rains slowed the march as tramping feet churned the roads into mud. In places, Crook's engineers had to build bridges across wash-outs before the army could advance.

The column reached Fayette on May 2, and then passed through Raleigh Court House and Princeton. On the night of May 8, the division camped at Shannon's Bridge, Virginia, 10 miles (16 km) north of Dublin.

The Confederates at Dublin soon learned the enemy was approaching. Their commander, Colonel John McCausland, prepared to evacuate his 1100 men, but before transportation could arrive, a courier from Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins informed McCausland that the two of them were ordered by General John C. Breckinridge to stop Crook's advance. The combined forces of Jenkins and McCausland amounted to 2,400 men. Jenkins, the senior officer, took command.

Breaking camp on the morning of May 9, Crook moved his men south to the top of a spur of Cloyd's Mountain. Before the Union troops lay a precipitous, densely wooded slope with a meadow about 400 yards wide at the bottom. On the other side of the meadow, the land rose in another spur of the mountain, and there Jenkins' rebels waited behind hastily erected fortifications.

Crook dispatched the third brigade under Colonel Carr B. White to work its way through the woods and deliver a flank attack on the rebel right. At 11 am, he sent Hayes' first brigade and Colonel Horatio G. Sickel's second brigade down the slope to the edge of the meadow, where they were to launch a frontal assault on the Confederates as soon as they heard the sound of White's guns.

The slope before them was so steep that the officers had to dismount and descend on foot. Crook stationed himself with Hayes' brigade, which was to lead the assault. After a long, anxious wait, Hayes at last heard cannon fire off to his left and led his men at a slow double time out onto the meadow and into the rebels' musketry and artillery fire, which Crook called "galling". Their pace quickened as they neared the other side, but just before the up-slope they came to a waist-deep creek. The barrier caused little delay and the Yankee infantry stormed up the hill and engaged the rebel defenders at close range.

The only man to have trouble with the creek was General Crook. Dismounted, he still wore his high riding boots, and as he stepped into the stream, the boots filled with water and bogged him down. Nearby soldiers grabbed their commander's arms and hauled him to the other side.

Vicious hand-to-hand fighting erupted as the Yankees reached the crude rebel defenses. The Southerners gave way, tried to re-form, then broke and retreated up and over the hill towards Dublin.

The Yankees rounded up rebel prisoners by the hundreds and seized General Jenkins, who had fallen wounded. At this point the discipline of the Union men wavered, and there was no organized pursuit of the fleeing enemy. General Crook was unable to provide leadership as the excitement and exertion had sent him into a faint.

Colonel Hayes kept his head and organized a force of about 500 men from the soldiers milling about the site of their victory. With his improvised command, he set off, closely pressing the rebels.

While the fight at Cloyd's Mountain was going on, a train pulled into the Dublin station and disgorged 500 fresh troops of General John Hunt Morgan's cavalry, which had just diverted Averell away from Saltville. The fresh troops hastened towards the battlefield, where they soon met their compatriots retreating from Cloyd's Mountain. The reinforcements halted the rout, but Colonel Hayes, although ignorant of the strength of the force now before him, immediately ordered his men to "yell like devils" and rush the enemy. Within a few minutes General Crook arrived with the rest of the division, and the defenders broke and ran.

Cloyd's Mountain cost the Union army 688 casualties, while the rebels suffered 538 casualties.

Unopposed, Crook moved his command into Dublin, where he laid waste to the railroad and the military stores. He then sent a party eastward to tear up the tracks and burn the ties. The next morning the main body set out for their next objective, the New River bridge, a key point on the railroad, a few miles to the east.

The Confederates, now commanded by Colonel McCausland, waited on the east side of the New River to defend the bridge. Crook pulled up on the west bank, and a long, ineffective artillery duel ensued. Seeing that there was little danger from the rebel cannon, Crook ordered the bridge destroyed, and both sides watched in awe as the structure collapsed magnificently into the river. McCausland, without the resources to oppose the Yankees any further, withdrew his battered command to the east.

General Crook, supplies running low in a country not suited for major foraging, now entertained second thoughts about his orders to push on east and join Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley. At Dublin he had intercepted an unconfirmed report that General Robert E. Lee had beaten Grant badly in the Wilderness, which led him to consider whether the Confederate commander might not soon move against Crook with a vastly superior force.

Having accomplished the major part of his mission, destruction of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, Crook turned his men north and after another hard march, reached the Union base at Meadow Bluff, West Virginia.

Shenandoah Valley

[edit]That July Crook assumed command of a small force called the Army of the Kanawha. Crook was defeated at the Second Battle of Kernstown. Nevertheless, he was appointed as a replacement for David Hunter in command of the Department of West Virginia the following day. However Crook did not assume command until August 9.[8] Along with the title of his department Crook added "Army of West Virginia." Crook's army was soon absorbed into Philip H. Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah and for all practical purposes functioned as a corps in that unit. Although Crook's force kept its official designation as the Army of West Virginia,[9] it was often referred to as the VIII Corps.[10] The official VIII Corps of the Union Army was led by Lew Wallace during this time and its troops were on duty in Maryland and Northern Virginia.[11]

Crook led his corps in the Valley Campaigns of 1864 at the battles of Opequon (Third Winchester), Fisher's Hill, and Cedar Creek. On October 21, 1864, he was promoted to major general of volunteers.

In February 1865 General Crook was captured by Confederate raiders at Cumberland, Maryland, and held as a prisoner of war in Richmond until exchanged a month later. He very briefly returned to command the Department of West Virginia until he took command of a cavalry division in the Army of the Potomac during the Appomattox Campaign. Crook first went into action with his division at the battle of Dinwiddie Court House. He later took a prominent role in the battles of Five Forks, Amelia Springs, Sayler's Creek and Appomattox Court House.

Indian Wars

[edit]At the end of the Civil War, George Crook received a brevet as major general in the regular army, but reverted to the permanent rank of major. Only days later, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel, serving with the 23rd Infantry on frontier duty in the Pacific Northwest. In 1867, he was appointed head of the Department of the Columbia.

Snake War

[edit]Crook successfully campaigned against the Snake Indians in the 1864–68 Snake War, where he won nationwide recognition. Crook had fought Indians in Oregon before the Civil War. He was assigned to the Pacific Northwest to use new tactics in this war, which had been waged for several years. Crook arrived in Boise to take command on December 11, 1866. The general noticed that the Northern Paiute used the fall, winter and spring seasons to gather food, so he adopted the tactic recommended by a predecessor George B. Currey to attack during the winter.[12] Crook had his cavalry approach the Paiute on foot in attack at their winter camp. As the soldiers drew them in, Crook had them remount; they defeated the Paiute and recovered some stolen livestock.[13]

Crook used Indian scouts as troops as well as to spot enemy encampments. While campaigning in Eastern Oregon during the winter of 1867, Crook's scouts located a Paiute village near the eastern edge of Steens Mountain. After covering all the escape routes, Crook ordered the charge on the village while intending to view the raid from afar, but his horse got spooked and galloped ahead of Crook's forces toward the village. Caught in the crossfire, Crook's horse carried the general through the village without being wounded. The army caused heavy casualties for the Paiute in the Battle of Tearass Plain.[14] Crook later defeated a mixed band of Paiute, Pit River, and Modoc at the Battle of Infernal Caverns in Fall River Mills, California.

Yavapai War

[edit]

President Ulysses S. Grant next placed Crook in command of the Arizona Territory. Crook's use of Apache scouts during his Tonto Basin Campaign of the Yavapai War brought him much success in forcing the Yavapai and Tonto Apache onto reservations. Crook's victories during the Yavapai War included the Battle of Salt River Canyon, also known as the Skeleton Cave Massacre, and the Battle of Turret Peak.

In 1873, Crook was appointed brigadier general in the regular army, a promotion that passed over and angered several full colonels next in line.

Great Sioux War

[edit]From 1875 to 1882 and again from 1886 to 1888, Crook was head of the Department of the Platte, with headquarters at Fort Omaha in North Omaha, Nebraska.

Battle of the Rosebud

[edit]On 28 May 1876, Crook assumed direct command of the Bighorn and Yellowstone Expedition at Fort Fetterman. Crook had gathered a strong force from his Department of the Platte. Leaving Fort Fetterman on 29 May, the 1,051-man column consisted of 15 companies from the 2d and 3d Cavalry, 5 companies from the 4th and 9th Infantry, 250 mules, and 106 wagons. On 14 June, the column was joined by 261 Shoshone and Crow allies. Based on intelligence reports, Crook ordered his entire force to prepare for a quick march. Each man was to carry only 1 blanket, 100 rounds of ammunition, and 4 days' rations. The wagon train would be left at Goose Creek, and the infantry would be mounted on the pack mules.

On 17 June, Crook's column set out at 0600, marching northward along the south fork of Rosebud Creek. The Crow and Shoshone scouts were particularly apprehensive. Although the column had not yet encountered any sign of Indians, the scouts seemed to sense their presence. The soldiers, particularly the mule-riding infantry, seemed fatigued from the early start and the previous day's 35-mile (56 km) march. Accordingly, Crook stopped to rest his men and animals at 0800. Although he was deep in hostile territory, Crook made no special dispositions for defense. His troops halted in their marching order. The Cavalry battalions led the column, followed by the battalion of mule-borne foot soldiers, and a provisional company of civilian miners and packers brought up the rear.

The Crow and Shoshone scouts remained alert while the soldiers rested. Several minutes later, the soldiers heard the sound of intermittent gunfire coming from the bluffs to the north. As the intensity of fire increased, a scout rushed into the camp shouting, "Lakota, Lakota!", the Battle of the Rosebud had begun. By 0830, the Sioux and Cheyenne had engaged Crook's Indian allies on the high ground north of the main force. Greatly outnumbered, the Crow and Shoshone scouts fell back toward the camp, their fighting withdrawal gave Crook enough time to deploy his forces. The soldiers rapid fire drove off the attackers but used up much of their ammunition which was meant to last the entire campaign. Low on ammunition and with numerous wounded, General Crook decided to return to Fort Fetterman.

Historians debate whether the killing of the five companies of the 7th Cavalry Regiment under the command of George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn could've been prevented, had Crook not retreated but instead pressed his advantage.

Battle of Slim Buttes

[edit]

After the disaster at the Little Bighorn, the U.S. Congress authorized funds to reinforce the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition.[15] Determined to demonstrate the willingness and capability of the U.S. Army to pursue and punish the Sioux, Crook took to the field. After briefly linking up with General Alfred Terry, military commander of the Dakota Territory, Crook embarked on what came to be known as the grueling and poorly provisioned Horsemeat March, upon which the soldiers were reduced to eating their horses and mules. A party dispatched to Deadwood for supplies came across the village of American Horse on September 9, 1876. The well-stocked village was attacked and looted in the Battle of Slim Buttes. Crazy Horse led a counter-attack against Crook the next day, but was repulsed by Crook's superior numbers.

Standing Bear v. Crook

[edit]In 1879, Crook spoke on behalf of the Ponca tribe and Native American rights during the trial of Standing Bear v. Crook. The federal judge affirmed that Standing Bear had some of the rights of U.S. citizens.

That same year his home at Fort Omaha, now called the General Crook House and considered part of North Omaha, was completed.

Geronimo's War

[edit]

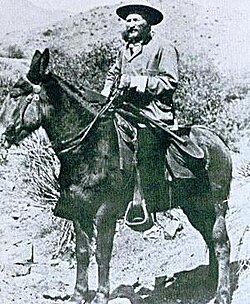

Crook was made head of the Department of Arizona and successfully forced some members of the Apache to surrender, but Geronimo continually evaded capture. As a mark of respect, the Apache nicknamed Crook Nantan Lupan, which means "Chief Wolf". In March, 1886, Crook received word that Geronimo would meet him in Cañon de los Embudos, in the Sierra Madre Mountains about 86 miles (138 km) from Fort Bowie. During the three days of negotiations, photographer C. S. Fly took about 15 exposures of the Apache on 8 by 10 inches (200 by 250 mm) glass negatives.[16] One of the pictures of Geronimo with two of his sons standing alongside was made at Geronimo's request. Fly's images are the only existing photographs of Geronimo's surrender. His photos of Geronimo and the other free Apaches, taken on March 25 and 26, are the only known photographs taken of an American Indian while still at war with the United States.[17]

Geronimo, camped on the Mexican side of the border, agreed to Crook's surrender terms. That night, a soldier who sold them whiskey said that his band would be murdered as soon as they crossed the border. Geronimo and 25 of his followers slipped away during the night; their escape cost Crook his command.[16]

Nelson A. Miles replaced Crook in 1886 in command of the Arizona Territory and brought an end to the Apache Wars. He captured Geronimo and the Chiricahua Apache band, and detained the Chiricahua scouts, who had served the U.S. Army, transporting them all as prisoners-of-war to a prison in Florida. (Crook was reportedly furious that the scouts, who had faithfully served the Army, were imprisoned along with the hostile warriors. He sent numerous telegrams protesting their arrest to Washington. They, along with most of Geronimo's band, were forced to spend the next 26 years in captivity at the fort in Florida before they were finally released.) [18]

After years of campaigning in the Indian Wars, Crook won steady promotion back up the ranks to the permanent grade of Major General. President Grover Cleveland placed him in command of the Military Division of the Missouri in 1888.

Later life

[edit]Crook served in Omaha again as the Commander of the Department of the Platte from 1886 to 1888. While he was there, his portrait was painted by artist Herbert A. Collins.[19]

Crook was a Veteran Companion of the Ohio Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States and was assigned insignia number 6512.

Crook was a charter member of the Illinois Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. He was elected as its first president on February 21, 1890 and died one month later.

Crook spent his last years speaking out against the unjust treatment of his former Indian adversaries. He died suddenly in Chicago in 1890 while serving as commander of the Military Division of the Missouri. Crook was originally buried in Oakland, Maryland. In 1890, Crook's remains were transported to Arlington National Cemetery, where he was reinterred on November 11.[20]

Red Cloud, a war chief of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux), said of Crook, "He, at least, never lied to us. His words gave us hope."[21]

Legacy

[edit]

His good friend and Union Army subordinate, future President Rutherford B. Hayes, named one of his sons George Crook Hayes (1864–1866), in honor of his commanding officer. The little boy died before his second birthday of scarlet fever.

Crook Counties in Wyoming and Oregon were named for him, as was the town of Crook, Colorado.

"Crook City," an unincorporated place in the Black Hills of South Dakota, was named for his 1876 camp there. Nearby and between Deadwood and Sturgis, South Dakota is Crook Mountain, named for him. Crook City Road passes through there from Whitewood heading toward Deadwood.

Crook Peak in Lake County, Oregon, elevation 7,834 feet (2,388 m),[22] in the Warner Mountains is named after him. It is near where the general set up Camp Warner (1867–1874) in a campaign to subdue the Paiute Indians.

Crook Mountain in Chelan County, Washington, elevation 6,930 feet (2,110 m),[23] a peak in the North Cascades, was named for him.

Cañon Pintado Historic District, 10 miles (16 km) south of Rangely, Colorado, has numerous ancient Fremont culture (0–1300 CE) and Ute petroglyphs, first seen by Europeans in the mid-18th century. One group of carvings, believed to be Ute after adoption of the horse in the 1600s, has several horses, which locals call "Crook's Brand Site". They claim the horses carry the general's brand.

Forest Road 300 in the Coconino National Forest is named the "General Crook Trail." It is a section of the trail which his troops blazed from Fort Verde to Fort Whipple, and on to Fort Apache through central Arizona.

Numerous military references honor him: Fort Crook (1857–1869) was an Army post near Fall River Mills, California, used during the Indian Wars. Later during the Civil War, it was used for the defense of San Francisco. It was named for then Lt. Crook by Captain John W. T. Gardiner, 1st Dragoons, as Crook was recovering there from an injury. California State Historical Marker 355 marks the site in Shasta County.

Fort Crook (1891–1946) was an Army Depot in Bellevue, Nebraska, first used as a dispatch point for Indian conflicts on the Great Plains. Later it served as airfield for the 61st Balloon Company of the Army Air Corps. It was named for Brig. Gen. Crook due to his many successful Indian campaigns in the west. The site formerly known as Fort Crook is now part of Offutt AFB, Nebraska.

3rd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division is nicknamed "Greywolf" in his honor, in a variation of his Apache nickname meaning "Chief Wolf".

The General Crook House at Fort Omaha in Omaha, Nebraska is named in his honor, as he was the only Commander of the Department of the Platte to live there. At Fort Huachuca, Crook House on Old Post is named after him as well. The Crook Walk in Arlington National Cemetery is near General Crook's gravesite.

In popular media

[edit]- Crook was portrayed in the 1993 movie Geronimo: An American Legend (1993) by the actor Gene Hackman.[24][25][26]

- He was represented in The West in a voiceover by Eli Wallach.

- He was a figure in the television series Deadwood and was portrayed by Peter Coyote.[27]

- A character named Grey Wolf appears in the video game Call of Juarez: Gunslinger. The game's flavor text explains that the character was inspired by Crook's Apache-given title.[28]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Eicher & Eicher 2001, pp. 191–92.

- ^ Warner 1964, pp. 102–04.

- ^ "Guide to the George Crook Papers 1863–1890". Orbis Cascade Alliance. Northwest Digital Archives. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ "Native Languages of the Americas". Native Languages. Blogspot. October 30, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Magid, Paul (2011). George Crook: From the Redwoods to Appomattox. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806144412.

- ^ Goodman, Rebecca (2005). This Day in Ohio History. Emmis Books. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-57860-191-2. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Eicher p. 191

- ^ Eicher p. 852

- ^ Eicher p. 857

- ^ "Civil War Archive". Civil War Archive. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ Eicher p. 859

- ^ Oregon Historical Quarterly Vol. 79 (1978) p. 132

- ^ Nelson, Kurt. Fighting For Paradise: A Military History of the Pacific Northwest, Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, 2007, p. 167

- ^ Michno, Gregory. The Deadliest Indian War in the West; The Snake Conflict, 1864–1868, Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press, 2007, pp. 202–203

- ^ Utley, Robert M. (1973) Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian 1866–1890, pp. 64, 69, note 11.

- ^ a b Vaughan, Thomas (1989). "C.S. Fly Pioneer Photojournalist". The Journal of Arizona History. 30 (3) (Autumn, 1989 ed.): 303–318. JSTOR 41695766.

- ^ "Mary "Mollie" E. Fly (1847–1925)". Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- ^ "A real injustice was done to these two old scouts: A VA claim file of an Indian Scout". October 31, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ Biography of Herbert Alexander Collins, by Alfred W. Collins, February 1975, 4 pages typed, in the possession of Collins' great-great grand-daughter, D. Dahl of Tacoma, WA

- ^ Burial of General Crook. His Remains Deported in the Arlington Cemetery. In: The Martinsburg Herald. Vol. 10. No. 10: November 15, 1890, p. 1 (Chronicling America).

- ^ Schmitt, p. . [page needed]

- ^ "Crook Peak, Oregon". Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ "Crook Mountain, Washington". Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 10, 1993). "Reviews/Film; A Revisionist Portrait Of an Apache Warrior". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (December 5, 1993). "Geronimo: An American Legend". Variety. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (December 12, 1993). "Geronimo: An American Legend". Variety. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ Beck, Henry Cabot (January 30, 2010). "On the Set of The Gundown". True West Magazine. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ Fleve (2006). "Part 6: Last of the Chiricahua". Let's Play Archive. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Aleshire, Peter, The Fox and the Whirlwind: General George Grook and Geronimo, Castle Books, 2000, ISBN 0-7858-1837-5.

- Bourke, John Gregory (1892). On the Border with Crook. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001). Civil War high commands. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Magid, Paul. George Crook: From the Redwoods to Appomattox (University of Oklahoma Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-8061-4207-4).

- Magid, Paul. The Gray Fox: George Crook and the Indian Wars (2015) vol 2

- Robinson, Charles M., III. "General Crook and the Western Frontier", Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

- Schmitt, Martin F., General George Crook, His Autobiography, University of Oklahoma Press, 1986 ISBN 0-8061-1982-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. (1964). Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)