Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

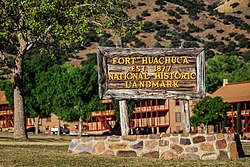

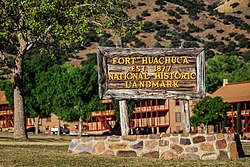

Fort Huachuca

View on Wikipedia

Fort Huachuca is a United States Army installation in Cochise County in southeast Arizona, approximately 15 miles (24 km) north of the border with Mexico and at the northern end of the Huachuca Mountains, adjacent to the town of Sierra Vista. Established on 3 March 1877 as Camp Huachuca, the garrison is under the command of the United States Army Installation Management Command. From 1913 to 1933, the fort was the base for the "Buffalo Soldiers" of the 10th Cavalry Regiment. During the build-up of World War II, the fort had quarters for more than 25,000 male soldiers and hundreds of WACs. In the 2010 census, Fort Huachuca had a population of about 6,500 active duty soldiers, 7,400 military family members, and 5,000 civilian employees. Fort Huachuca has over 18,000 people on post during weekday work hours.

Key Information

The major tenant units are the United States Army Network Enterprise Technology Command (NETCOM) and the United States Army Intelligence Center. Libby Army Airfield is on post and shares its runway with Sierra Vista Municipal Airport. It was an alternate but never used landing location for the Space Shuttle. Fort Huachuca is the headquarters of Army Military Auxiliary Radio System. Other units include the Joint Interoperability Test Command, the Information Systems Engineering Command, the Electronic Proving Ground (USAEPG), and the Intelligence and Electronic Warfare Directorate.[5]

The fort has a radar-equipped aerostat (Tethered Aerostat Radar System), one of a series maintained for the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) by Harris Corporation. The aerostat is northeast of Garden Canyon and supports the DEA drug interdiction mission by detecting low-flying aircraft attempting to enter the United States from Mexico. Fort Huachuca contains the Western Division of the Advanced Airlift Tactics Training Center which is based at the 139th Airlift Wing, Rosecrans Air National Guard Base in Saint Joseph, Missouri.

History

[edit]The installation was founded to counter the Chiricahua Apache threat and secure the border with Mexico during the Apache Wars. On 3 March 1877, Captain Samuel Marmaduke Whitside led two companies of the 6th Cavalry and chose a site at the base of the Huachuca Mountains that provided sheltering hills and a perennial stream.[6][7] In 1882, Camp Huachuca was redesignated a fort.

General Nelson A. Miles commanded Fort Huachuca as his headquarters in his campaign against Geronimo in 1886. After the surrender of Geronimo in 1886, the Apache threat was extinguished, but the army continued to operate Fort Huachuca because of its strategic border position. In 1913, the fort became the base for the "Buffalo Soldiers", the 10th Cavalry Regiment composed of African Americans. It served this purpose for twenty years. During General Pershing's failed Punitive Expedition of 1916–1917, he used the fort as a forward logistics and supply base. From 1916 to 1917, the base was commanded by Charles Young, the first African American to be promoted to colonel. He left for medical reasons. In 1933, the 25th Infantry Regiment replaced the 10th Cavalry at the fort.

With the build-up during World War II, the fort had an area of 71,253 acres (288.35 km2), with quarters for 1,251 officers and 24,437 enlisted soldiers.[8] The 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions, composed of African-American troops, trained at Huachuca.

In 1947, the post was closed and turned over to the Arizona Game and Fish Department. At the outbreak of the Korean War, a January 1951 letter from the Secretary of the Air Force to the Governor of Arizona invoked the reversion clause of a 1949 deed. On 1 February 1951 the U.S. Air Force took official possession of Fort Huachuca, making it one of the few army installations to have had an existence as an air base.[9] The army retook possession of the base a month later and reopened the post in May 1951 to train engineers in airfield construction as part of the Korean War build up. The engineers built today's Libby Army Airfield, named in honor of Korean War Medal of Honor recipient George D. Libby. On 1 May 1953, after the Korean War, the post was again placed on inactive status with only a caretaker detachment.

On 1 February 1954, Huachuca was reactivated after a seven-month shut-down following the Korean War. It was the beginning of a new era focused on electronic warfare. The army's Electronic Proving Ground opened in 1954, followed by the Army Security Agency Test and Evaluation Center in 1960, the Combat Surveillance and Target Acquisition Training Command in 1964, and the Electronic Warfare School in 1966. Also in 1966 the U.S. Army established the 1st Combat Support Training Brigade, whose mission was to train soldiers in the specialties of field wire and communication, telegraph communications (O5B wired and wireless)[clarification needed], light tactical vehicle driving, wheeled vehicle maintenance, and food service and administration due to the expanding need for these skills in Vietnam.

In 1967, Fort Huachuca became the headquarters of the U.S. Army Strategic Communications Command, which became the U.S. Army Communications Command in 1973, and U.S. Army Information Systems Command in 1984. It is now known as NETCOM after the army dropped the 9th Signal Command (Army) designation on 1 October 2011. NETCOM was realigned in 2014 as a subordinate command to United States Army Cyber Command from a direct reporting unit to the Headquarters, Department of the Army CIO/G6.[10]

Fort Huachuca was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976 for its role in ending the Apache Wars, the last major military actions against Native Americans, and as the site of the Buffalo Soldiers.[4][11][12] Fort Huachuca includes a cemetery known as the Fort Huachuca Post Cemetery.[13] Some 3,800 veterans and family members are buried there.

In 1980, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR) conducted aircraft training exercises from Fort Huachuca in preparation for Operation Honey Badger. This operation aimed to rescue captive American personnel in Iran. It was developed in the wake of Operation Eagle Claw's failure. The environment near the fort enabled 160th SOAR pilots to train and simulate flying in the mountainous desert terrain of Iran.

The fort was the site of the 2007 Conseil International du Sport Militaire.[citation needed]

Museums

[edit]

Fort Huachuca has two museums in three buildings on post. The Ft. Huachuca Museum[14] occupies two buildings on Old Post, its main museum and gift shop (Building 41401), and a nearby spillover gallery called the Museum Annex (building 41305). It tells the story of Fort Huachuca and the U.S. Army in the American Southwest, with special emphasis on the Buffalo Soldiers and the Apache War. The Annex across the street (Old Post Theater) has outdoor displays, walkways, sitting areas, and historical statues.

The second museum is The U.S. Army Intelligence Museum, in the military intelligence (MI) Library on the MI school campus (Hatfield Street – Building 62723). The museum has a collection of historical artifacts including agent radio communication gear, aerial cameras, cryptographic equipment, an Enigma Code machine, two small drones and a section of the Berlin Wall. The museum's emphasis is on U.S. Army military intelligence history and includes displays of the organizational development of army intelligence. There is a small military intelligence gift shop with customized Fort Huachuca souvenirs.

All visitors, military or civilian, are welcome at the Ft. Huachuca Museum free of charge. Civilian visitors without a DoD ID card must pass a criminal background check before being allowed to pass the gate.[15] Foreign visitors must be escorted by active duty or retired military personnel.

Signal Commands

[edit]Fort Huachuca has a rich tradition in Army Signal and is currently home to NETCOM whose mission is to plan, engineer, install, integrate, protect, defend and operate army cyberspace, enabling mission command through all phases of operations. It used to be home to the 11th Signal Brigade. The 11th Signal Brigade has the mission of rapidly deploying worldwide to provide and protect command, control, communications, and computer support for commanders. They were deployed to provide signal operations during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. On 7 June 2013, the unit moved to Fort Hood, Texas. The Army Electronic Proving Ground (USAEPG), a forerunner in the research and development of defense technology, was conducted at Ft. Huachuca for several decades. The software-defined radios, Wideband Networking Waveform, and the Soldier Radio Waveform, were tested at USAEPG in 2014 for a network integration evaluation, NIE 15.2, at Fort Bliss, in 2015.[16]

Military Intelligence

[edit]In addition to the US Army Intelligence Center, Fort Huachuca is the home of the 111th Military Intelligence Brigade, which conducts MI training for the armed services. The Military Intelligence Officer Basic Leadership Course, Military Intelligence Captain's Career Course, and the Warrant Officer Basic and Advanced Courses are taught on the installation. The Army's MI branch also held the responsibility for unmanned aerial vehicles until April 2006. The program was reassigned to the Aviation branch's 1st Battalion, 210th Aviation Regiment, now 2nd Battalion, 13th Aviation Regiment. Additional training in Human Intelligence (e.g., interrogation, counterintelligence), Imagery Intelligence, and Electronic Intelligence and analysis is also conducted by the 111th. The 111th MI Brigade hosts the Joint Intelligence Combat Training Center at Fort Huachuca.

Education

[edit]Fort Huachuca Accommodation Schools is the school district for dependent children living on the base.[17] The schools are: Colonel Johnston Elementary School (K–2), General Myer Elementary School (3–5), and Colonel Smith Middle School (6–8).[18] The zoned high school is Buena High School, operated by the Sierra Vista Unified School District, in Sierra Vista.[19]

Notable people

[edit]

People who have served or lived at Fort Huachuca:

- Brigadier General Samuel Whitside, founded Camp Huachuca.

- Major General Leonard Wood, Medal of Honor recipient and Chief of Staff of the Army from 1910 to 1914 (after whom Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri is named).

- Colonel Cornelius C. Smith, Medal of Honor recipient and head of the Philippine Constabulary from 1910 to 1912. He accepted surrender of Mexican Colonel Emilio Kosterlitzky while stationed at Huachuca in 1913 and was later Huachuca commandant from 1918 to 1919.

- Bullet Rogan (Negro league baseball) 25th Infantry Regiment

- Cornelius C. Smith Jr., historian of Arizona, California, and the Southwestern United States.

- John Henry, played professional baseball for the Washington Senators and Boston Braves from 1910 to 1918.

- Colonel Sidney Mashbir, Commandant of Allied Translator and Interpreter Section, Military Intelligence Service during World War II.

- General Alexander Patch, decorated officer who commanded Army and Marine forces in the Guadalcanal campaign and later the 7th Army in Europe during World War II.

- General James Gavin (82nd Airborne Division)

- General Robert Sink (101st Airborne Division)

- Lieutenant General Sidney T. Weinstein, one of the driving forces behind reorganizing Army intelligence in late 1970s and 1980s.

- Captain Amadou Sanogo, junta leader in the West African country of Mali, completed intelligence training at Fort Huachuca in 2008.

- Specialist 5 Bobby Murcer, Major League Baseball player, New York Yankees, 1967–1969. 1st Training Brigade.

- Luis Robles, goalkeeper for the New York Red Bulls of Major League Soccer, was born at Fort Huachuca in 1984.

- Jayne Cortez, poet, born at Fort Huachuca in 1934.

- Lieutenant General Robert P. Ashley Jr., served as the Commanding General of the Army Intelligence Center of Excellence and Fort Huachuca from April 2013 to July 2015.[20]

- Lieutenant General Scott D. Berrier, served as the Commanding General of the Army Intelligence Center of Excellence and Fort Huachuca from July 2015 to July 2017.[21]

In popular culture

[edit]- Captain Newman, M.D. (1963), starring Gregory Peck as the title character, was filmed at Fort Huachuca.

- The opening sequence of Suppose They Gave a War and Nobody Came (1969) was filmed at Ft. Huachuca. This movie was supported by the 1st Training Brigade. It stars Brian Keith and Tony Curtis.

- In Scent of a Woman (1992) starring Al Pacino as Lt. Colonel Frank Slade, Slade tells his companion Charlie Simms that he dreamed of The Oak Room's rolls when he was at Fort Huachuca. "Bread's no good west of the Colorado. Water's too alkaline."

- In the Tom Clancy thriller, Clear and Present Danger, Fort Huachuca is identified and shown as the place where phone calls between drug lords, Felix Cortez and Ernesto Escobedo, are being intercepted.

- Tumbleweed Forts (2021), a memoir by Frank Warner, describes how Frank and his brothers explored Fort Huachuca from 1960 to 1963, when their father was stationed there experimenting with the Army's early drones. Tumbleweed Forts also has been turned into a five-part series, Huachuca Books, adapted for young readers.

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Fort Huachuca, Arizona | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

84 (29) |

88 (31) |

96 (36) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

102 (39) |

99 (37) |

89 (32) |

81 (27) |

105 (41) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58.8 (14.9) |

61.6 (16.4) |

67.3 (19.6) |

74.1 (23.4) |

81.5 (27.5) |

90.9 (32.7) |

89.3 (31.8) |

87.3 (30.7) |

84.6 (29.2) |

77.3 (25.2) |

67.0 (19.4) |

59.4 (15.2) |

74.9 (23.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.8 (1.0) |

35.9 (2.2) |

40.8 (4.9) |

46.1 (7.8) |

53.6 (12.0) |

63.0 (17.2) |

65.3 (18.5) |

63.5 (17.5) |

59.7 (15.4) |

51.0 (10.6) |

40.1 (4.5) |

34.6 (1.4) |

49.0 (9.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 1 (−17) |

4 (−16) |

18 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

32 (0) |

38 (3) |

44 (7) |

46 (8) |

35 (2) |

24 (−4) |

10 (−12) |

6 (−14) |

1 (−17) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.08 (27) |

0.94 (24) |

0.77 (20) |

0.27 (6.9) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.50 (13) |

3.83 (97) |

3.44 (87) |

1.73 (44) |

0.86 (22) |

0.74 (19) |

1.09 (28) |

15.47 (393) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.2 (3.0) |

2.0 (5.1) |

1.1 (2.8) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

1.9 (4.8) |

6.9 (18) |

| Source: http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?az3120. | |||||||||||||

Gallery

[edit]-

Fort Huachuca in 1918

-

Private William Major and Private Andrew Paxson on patrol of Fort Huachuca in 1942.

-

Aerial photograph of Fort Huachuca from the 1950s

-

Private Anthony Devlin operating a PPS-4 Radar System in 1956.

-

Fort Huachuca in 1970s

-

Aerial View of Fort Huachuca in the 1970s

-

USAF Security Forces on a training exercise at Fort Huachuca.

-

American Boyd Melson (right), during the 2007 Military World Games, at which he won a gold medal at Fort Huachuca

-

The Huachuca Mountains are the backdrop of several ranges on Fort Huachuca.

-

Fort Huachuca Old Post

-

Huachuca Mountains

-

Overlooking Fort Huachuca from Reservoir Hill

-

Overlooking Fort Huachuca (Old Post) from Reservoir Hill

-

Hangman's Warehouse built in1880 in Fort Huachuca

-

The Carleton House-1880 in Fort Huachuca

-

Old Post Cemetery established in 1877 in Fort Huachuca

-

Old Post Cemetery grounds

-

Mourning Hearts Statue

-

Sam Kee Hall built in 1885 in Fort Huachuca

-

John J. Pershing House built in 1884 in Fort Huachuca

-

Rodney Hall built in1917 in Fort Huachuca

-

Old Post Barracks built in 1882 in Fort Huachuca

-

Mountain View Officers' Club, Fort Huachuca, Arizona, Photo C. 1943

References

[edit]- ^ "Invitation Letter from BG Hiestand to LTG Walters" (PDF). cia.gov/library. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Photograph/color portrait of BG Stubblebine". azmemory.azlibrary.gov. Arizona Memory Project. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 23 January 2007.

- ^ a b "Fort Huachuca". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2007.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca Units/Tenants". home.army.mil/huachuca/. United States Army. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Russell, Major Samuel L., "Selfless Service: The Cavalry Career of Brigadier General Samuel M. Whitside from 1858 to 1902." MMAS Thesis, Fort Leavenworth: U.S. Command and General Staff College, 2002.

- ^ "History of Fort Huachuca". home.army.mil/huachuca. United States Army. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Stanton, Shelby L. (1984). Order of Battle: U.S. Army World War II. Novato, California: Presidio Press. p. 600. ISBN 089141195X.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca Army Base in Cochise, Arizona | MilitaryBases.com". militarybases.com. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca – General History", U.S. Army Intelligence Center and Fort Huachuca, Accessed 2 March 2018

- ^ George R. Adams (January 1976). ""Fort Huachuca", National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination". National Park Service.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca –Accompanying photos, 12 from 1976, 4 from c. 1890, 5 from 1975; National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination". National Park Service. January 1976.

- ^ Sierra Vista, Arizona : history : more than what you learned in school. Sierra Vista: City of Sierra Vista : Sierra Vista Visitor Center, Sierra Vista. 2012. OCLC 1222862119.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca Museum and Annex – U.S. Army Center of Military History".

- ^ "The United States Army". Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Right frequency for radio testing: Teaming, innovation Retrieved 2015-05-28[full citation needed]

- ^ "2020 Census – School District Reference Map: Cochise County, AZ" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 25 July 2022. – Text list

- ^ "Home". Fort Huachuca Accommodation Schools. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca Education". Military One Source. Retrieved 25 July 2022. – this website has a .mil domain.

- ^ Vasey, Joan (6 August 2015). "New commander takes charge of Fort Huachuca during July 31 ceremony". United States Army. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ "Search". AFCEA International.

Further reading

[edit]- Smith, Cornelius C. Jr. Fort Huachuca: The Story of a Frontier Post. Fort Huachuca, Arizona: 1978.[ISBN missing]

External links

[edit]Fort Huachuca

View on GrokipediaGeography and Location

Physical Setting and Infrastructure

Fort Huachuca occupies an irregularly shaped area of approximately 115 square miles (73,600 acres) in Cochise County, southeastern Arizona, bisected by Arizona State Highway 90 and situated at the base of the Huachuca Mountains.[11][12] The installation lies along the northeastern foothills of these mountains, which form part of the Sky Island ranges rising nearly 4,500 feet above the surrounding desert floor, with grassland expanses at elevations of 3,500 to 5,000 feet transitioning into higher mountain islands exceeding 9,000 feet.[13][14] The terrain features high-desert scrub, pediments, floodplains, and washes, providing a mix of arid lowlands and rugged uplands conducive to military training in varied environments.[15][16] The local climate is mild, sunny, and arid, with average annual temperatures ranging from lows of about 37°F in winter to highs near 93°F in summer, moderated by the higher elevation compared to lower Arizona deserts.[15][17] Precipitation is low, averaging under 15 inches yearly, primarily during summer monsoons, supporting sparse vegetation like mesquite and cactus in the valleys.[18] Infrastructure centers on a main cantonment area housing the bulk of facilities, including over 1,900 buildings encompassing more than 8 million square feet for administrative, training, barracks, and operational uses.[19] Key assets include training ranges, hangars for unmanned aerial systems (approximately 21,000 square feet), and support structures integrated into the mountainous backdrop for electronic warfare and intelligence exercises.[20][21] The layout emphasizes strategic placement amid natural barriers, with boundaries often aligning with the adjacent Coronado National Forest for expanded maneuver space.[22]Proximity to Borders and Strategic Positioning

Fort Huachuca is situated in Cochise County, southeastern Arizona, approximately 15 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border.[9] This positioning places the installation at coordinates roughly 31°31' N latitude and 110°21' W longitude, adjacent to rugged terrain including the Huachuca Mountains, which enhances its utility for surveillance and training operations overlooking cross-border activities.[1] The base's proximity to the border has historically facilitated rapid response to threats from Mexico, including Apache raids in the late 19th century that prompted its establishment in 1877 as a frontier outpost.[1] Strategically, the location supports intelligence and electronic warfare missions by providing realistic environments for monitoring border dynamics, such as narcotics trafficking and unauthorized crossings, without relying on simulated scenarios.[23] In recent developments, Fort Huachuca serves as the headquarters for a Joint Task Force activated in March 2025 by U.S. Northern Command to synchronize Department of Defense efforts in securing the southern border, leveraging its nearness for tactical oversight and logistics.[23] Interagency agreements have extended military authority over adjacent federal lands, designating portions of the Roosevelt Reservation along the New Mexico border as extensions of the fort, enabling service members to conduct detentions and searches to counter illegal activities.[24] The installation's border adjacency also bolsters testing of unmanned aerial systems and signal intelligence platforms, where real-world electromagnetic interference and terrain mimic operational challenges near international boundaries.[1] This positioning maintains Fort Huachuca's role as a key asset for national defense against asymmetric threats emanating from the porous southwestern frontier, a function unchanged since its founding despite evolving mission sets.[9]Historical Development

Establishment and Frontier Defense (1877–1912)

Camp Huachuca was established on March 3, 1877, by Captain Samuel Marmaduke Whitside of the 6th United States Cavalry, leading two companies, under orders from Colonel August V. Kautz, to serve as a frontier outpost in the Arizona Territory.[1][25] The site, at the mouth of Huachuca Canyon in the San Pedro Valley, was selected for its access to fresh water, timber, and elevated terrain offering visibility into surrounding valleys, enabling effective surveillance against Apache incursions.[1][26] Initially a temporary camp, it functioned to protect nearby settlements, mining operations, ranching interests, and transportation routes from Chiricahua Apache raids while blocking escape routes into Mexico.[25][26] In 1882, the camp was redesignated Fort Huachuca and upgraded to permanent status, with troops constructing adobe, stone, and wooden buildings to support sustained operations.[1][25] The fort played a pivotal role in the Apache Wars, particularly in 1886 when General Nelson A. Miles established it as an advance headquarters and supply base for campaigns against Geronimo and his band.[1][26] Troops conducted patrols, scouting missions, and engagements to subdue hostile Apaches, contributing to Geronimo's surrender on September 4, 1886, which effectively ended large-scale Apache resistance in the region.[25][26] Following the Apache Wars, the U.S. Army decommissioned over 50 garrisons in Arizona Territory, but retained Fort Huachuca due to its strategic border proximity and ongoing security needs.[1] From the late 1880s through 1912, the fort's garrison, primarily elements of the 6th Cavalry, focused on border patrols, peacekeeping, and responses to sporadic threats from renegade Indians, Mexican bandits, outlaws, and filibusters disrupting southeastern Arizona.[1][25] These operations maintained law and order in a volatile frontier environment, safeguarding economic activities until Arizona's statehood in 1912 and the decline of immediate territorial threats.[26]Buffalo Soldiers Era and Interwar Years (1913–1941)

In 1913, the 10th Cavalry Regiment, an African American unit known as the Buffalo Soldiers, arrived at Fort Huachuca and served as the primary garrison until 1933, marking the longest continuous assignment of any regiment at the post.[25] The regiment conducted extensive border patrol operations along the U.S.-Mexico border to counter smuggling and incursions during the Mexican Revolution. In March 1916, elements of the 10th Cavalry joined General John J. Pershing's Punitive Expedition into Mexico, pursuing Pancho Villa after his raid on Columbus, New Mexico; the unit advanced approximately 750 miles in 28 days, engaging in clashes such as the Battle of Carrizal on June 21, 1916, under commanders including Colonel William C. Brown and Major Charles Young.[27][28] During World War I, the 10th Cavalry maintained border security while some personnel trained in Huachuca Canyon using trenches, grenades, and gas masks, leading to the commissioning of 62 non-commissioned officers. In January 1918, troops from the regiment fought in the Bear Valley engagement against Yaqui smugglers, capturing nine prisoners, and participated in the Battle of Ambos Nogales on August 27, resulting in casualties on both sides amid cross-border tensions involving German agents.[27][29] Post-armistice, the fort emphasized cavalry and infantry training, including marksmanship—where Company E of the succeeding 25th Infantry Regiment achieved a National Rifle Association average score of 300.86 in 1933—and recreational equestrian events like polo matches.[27] The 25th Infantry Regiment, another Buffalo Soldier unit, arrived in March 1928, overlapping briefly with the 10th Cavalry's departure and continuing border patrols and reserve officer training for the 206th Infantry Brigade until 1941. Apache Indian Scouts, numbering around 22 by 1917, relocated to the post in November 1922 and supported scouting and maneuvers until their retirement in 1947. Infrastructure expansions included new officer quarters, barracks, a power plant, ice plant, and extended water and sewer systems by 1917, funded partly by $30,000 investments, followed by 1930s Works Progress Administration projects such as well drilling, road modernization, and reservoir construction to accommodate growing needs.[27][29] In the late interwar years, Fort Huachuca shifted toward infantry-focused preparedness, hosting Civilian Conservation Corps programs and large-scale maneuvers involving up to 70,000 troops by 1940. Troop strength rose from 1,143 in 1940 to 5,292 by year's end with the addition of the 368th Infantry Regiment, alongside $6 million in cantonment construction including 80 barracks and a 190-bed hospital, setting the stage for World War II mobilization.[29]World War II Expansion and Transition (1941–1960)

In anticipation of U.S. entry into World War II, Fort Huachuca underwent rapid expansion starting in 1941, with infrastructure improvements to accommodate large-scale training. The post transitioned from a regimental cavalry and infantry outpost to a major divisional training center, hosting the activation and preparation of African American infantry units under the segregated U.S. Army structure. By 1942, the 93rd Infantry Division was activated there, followed by the 92nd Infantry Division's arrival in 1943 after the 93rd's deployment to the Pacific Theater.[1][25] Training activities intensified during 1942–1943, peaking with up to 32,000 troops on site, including maneuvers simulating combat conditions in the fort's rugged desert terrain. The facility supported basic and advanced infantry drills, artillery practice with equipment such as the M2A1 105mm howitzer, and logistical operations for division-scale forces. Concurrently, Fort Huachuca became one of the earliest U.S. installations to host the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), later redesignated the Women's Army Corps (WAC) in 1943, with hundreds of women, including all-Black units like the 32nd and 33rd Post Headquarters Companies, undergoing training in administrative, clerical, and support roles. The post's population exceeded 30,000 personnel at its wartime height, necessitating expanded barracks, training fields, and support facilities leased from nearby lands.[1][30][31] Following Japan's surrender in 1945, Fort Huachuca was declared surplus property and briefly closed as demobilization reduced Army needs. Reactivation occurred in 1950 amid the Korean War buildup, initially repurposing the site as a training area for Army Engineer units focused on construction and combat support skills. By the mid-1950s, the fort shifted toward emerging technological roles, with the establishment of the Army's Electronic Proving Ground in 1954 to test and develop electronic warfare systems, marking an early transition from conventional infantry training to specialized electronic and signals intelligence capabilities. This evolution reflected broader post-war Army priorities in adapting to mechanized and technological warfare, leveraging the installation's isolated, arid environment for secure testing.[1][32]Evolution into Intelligence Hub (1961–Present)

In the early 1960s, Fort Huachuca began transitioning toward specialized roles in electronic warfare and communications, building on its postwar reactivation as an engineering training site in 1950 and the establishment of the Army's Electronic Proving Ground in 1954.[1] By 1964, the post hosted elements of the U.S. Army Training Command, which facilitated advanced testing and development of signal-related technologies critical to Cold War intelligence operations.[1] This period marked a shift from general-purpose training to focused capabilities in signals intelligence and electronic countermeasures, driven by the need to counter Soviet electronic threats.[33] The establishment of the U.S. Army Electronic Warfare School in 1966 solidified Fort Huachuca's emerging expertise in electronic warfare, providing doctrinal and technical training for personnel in spectrum management, jamming, and interception techniques.[1] In 1967, the headquarters of the U.S. Army Strategic Communications Command relocated to the installation, enhancing its role in secure communications infrastructure and laying foundational networks for intelligence dissemination.[2] These developments positioned the fort as a nexus for integrating communications with intelligence functions, amid escalating demands for technical superiority in Vietnam-era operations and broader deterrence strategies. A pivotal expansion occurred in 1971 when the U.S. Army Intelligence Center and School (USAICS) relocated from Fort Holabird, Maryland, to Fort Huachuca, centralizing military intelligence training under one roof.[34] [1] This move integrated counterintelligence, human intelligence, and signals intelligence curricula, training thousands of soldiers annually in disciplines such as interrogation, analysis, and surveillance. By the 1980s, the post had absorbed additional functions, including the Combat Surveillance and Electronic Warfare School, further embedding it in all-source intelligence production.[35] The activation of the Military Intelligence Corps on July 1, 1987, at Fort Huachuca formalized its status as the Army's premier intelligence institution, with the USAICS evolving into the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence (USAICoE) to emphasize advanced education and doctrine development.[36] Post-Cold War adaptations included expanded human intelligence training in 2007, addressing gaps in clandestine operations exposed by operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.[37] Today, the installation hosts the 111th Military Intelligence Brigade for operational training and the Electronic Proving Ground for testing unmanned aerial systems and cyber-electronic warfare tools, sustaining its core mission amid evolving threats like peer competitors' hypersonic and networked warfare capabilities.[1]Military Missions and Capabilities

Core Functions in Intelligence and Electronic Warfare

Fort Huachuca serves as the primary hub for U.S. Army military intelligence training through the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence (USAICoE), which develops and delivers doctrine, training, and capabilities for intelligence warfighting functions.[36] The center focuses on preparing soldiers for multi-domain operations, including signals intelligence (SIGINT), human intelligence (HUMINT), and electronic warfare (EW) integration to support tactical dominance.[38] This includes training in identifying enemy signals for EW operations and providing intelligence for force generation and situational understanding.[39][40] The Intelligence Electronic Warfare Test Directorate (IEWTD), aligned under the U.S. Army Operational Test Command, conducts independent operational testing of intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (ISR), EW, and counter-improvised explosive device systems.[41] Located at Fort Huachuca, IEWTD plans, executes, and reports mission-based tests to evaluate system performance in realistic environments, ensuring reliability for Army forces.[42] Complementing this, the U.S. Army Electronic Proving Ground (EPG) at the installation tests communications-electronics materiel, including EW components, leveraging the site's unique topography for spectrum management and interoperability assessments.[43] Fort Huachuca hosts experimentation events like Vanguard, where stakeholders test high-altitude sensors, terrestrial systems, microsensors, and EW capabilities to inform Army transformation and multi-domain integration.[44][45] These activities bridge training, testing, and vendor solutions to enhance deep sensing and operational readiness in contested electromagnetic environments.[40] The 111th Military Intelligence Brigade contributes by training personnel in surveillance equipment deployment, target tracking, and pattern analysis to support EW missions.[46]Signal Intelligence and Communications Roles

The 111th Military Intelligence Brigade, stationed at Fort Huachuca, delivers initial military training and professional education for signals intelligence (SIGINT) specialists, including military occupational specialty 35N signals intelligence analysts responsible for intercepting, analyzing, and reporting foreign communications and electronic activities to support operational decision-making.[46] This training encompasses tactical SIGINT (TACSIGINT) operations, where personnel deploy and maintain systems such as mine-resistant vehicles equipped with satellite communications, portable collection gear, and interception tools to capture enemy signals on the battlefield.[46] Additionally, the brigade supports specialized electronic mission aircraft training on RC-12 and MC-12 platforms, enabling fixed-wing SIGINT collection by pilots and crews to gather intelligence from airborne intercepts of adversary transmissions.[46] SIGINT functions at Fort Huachuca extend to network defense through the U.S. Army Network Enterprise Technology Command (NETCOM), headquartered there since its alignment with the installation, where SIGINT expertise is applied to secure Army networks by identifying threats, coordinating intelligence resources, and developing analyst training pipelines.[47] NETCOM's G2 intelligence directorate leverages SIGINT for cyberspace operations, advising on enemy communications patterns to protect the Department of Defense Information Network and deny adversaries access.[47] In communications roles, NETCOM oversees global operations and defense of the Army's portion of the Defense Department Information Network (DODIN), ensuring reliable command-and-control networks, spectrum management, and cybersecurity resilience for joint and multinational forces as of 2024.[48] This includes managing theater-level signal assets, integrating satellite and tactical communications, and sustaining network infrastructure to enable freedom of action in contested environments.[49] The Communication Security Logistics Activity (CSLA), a NETCOM-aligned entity at the fort, serves as the Army's primary manager for communications security (COMSEC) materials, handling distribution, accountability, and logistics for encryption devices and keys to safeguard classified transmissions.[50] Historically, Fort Huachuca supported expeditionary signal units like the 40th Expeditionary Signal Battalion under the 11th Signal Brigade until its inactivation in 2022, which provided deployable communications support for divisions, including radio relay, data networks, and voice systems during operations such as those in Iraq and the Horn of Africa.[51][52] Current communications efforts emphasize NETCOM's enterprise-level functions, including full-time support for DoDIN hardware, software, and applications to counter cyber intrusions.[48]Testing and Innovation Initiatives

Fort Huachuca hosts the U.S. Army Electronic Proving Ground (EPG), headquartered on the installation and tasked with developmental testing of command, control, communications, computers, cyber, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, electronic warfare, and assured positioning, navigation, and timing systems in support of Army Futures Command and program executive offices.[53] Established to test, prove, explore, and evaluate electronic systems and devices, the EPG leverages the site's diverse terrain and environmental conditions in southeastern Arizona for realistic evaluations of communications infrastructure, network systems, and electronic warfare capabilities.[43][54] The EPG conducts both developmental and operational testing to validate system performance under operational stresses, including interoperability assessments through elements like the Joint Interoperability Test Command, which certifies information technology and national security systems for risk reduction in warfighting environments.[53][55] The Intelligence Electronic Warfare Test Directorate, integrated within testing operations at the fort, performs independent operational tests of intelligence and electronic warfare equipment to ensure reliability and effectiveness.[45] Innovation efforts emphasize multi-domain experimentation, exemplified by the annual Vanguard series. Vanguard 23, held April 10–14, 2023, at the 1LT John R. Fox range, united government, commercial, and joint partners for multi-node experiments integrating testing and training commands with vendors.[45] Building on this, Vanguard 24 in 2024 focused on operationalizing intelligence experimentation, incorporating cyber operations, electronic warfare, extended-range sensing, and data fusion to advance multi-domain integration.[44][56] These initiatives foster collaboration with industry and academia, including small business innovation research programs and technology demonstrations at facilities like the Technology Innovation Center.[57] Annual Innovation Day events at Fort Huachuca provide platforms for military leaders and personnel to evaluate emerging technologies, engaging directly with industry solutions for intelligence and electronic warfare applications.[58] Such activities underscore the installation's role in bridging testing with rapid prototyping and fielding of advanced capabilities.[56]

Organizational Structure

Key Units and Tenants

The primary tenant at Fort Huachuca is the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence (USAICoE), which serves as the Army's premier institution for developing military intelligence (MI) doctrine, training, and capabilities.[36] USAICoE drives force modernization for the Intelligence Warfighting Function, enabling the Army to conduct large-scale combat operations in multi-domain environments through initiatives aligned with Army 2030-2040 objectives.[36] Commanded by Maj. Gen. Richard T. Appelhans since July 19, 2023, it encompasses programs for professional development, including the Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin and the MI Library.[36] Under USAICoE, the 111th Military Intelligence Brigade oversees initial military training, professional military education, and functional training to produce intelligence warfighters across all domains.[46] The brigade manages four subordinate MI battalions—the 304th, 305th, 309th, and 344th—which deliver specialized instruction in areas such as signals intelligence, human intelligence, and analysis.[59] The 2nd Battalion, 13th Aviation Regiment, a tenant unit focused on unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), was activated on April 19, 2006, and redesignated on June 14, 2011.[59] It conducts advanced individual training for approximately 2,000 Soldiers annually across 12 programs, including RQ-7B Shadow UAS operator and repairer courses, as well as integration of emerging systems like the RQ-28A small UAS.[60][61] Other significant tenants include the U.S. Army Network Enterprise Technology Command (NETCOM)/9th Signal Command, which supports network operations and cybersecurity; the Joint Interoperability Test Command (JITC), the Department of Defense's certifier for joint interoperability in information technology and national security systems; and the Communications Security Logistics Activity (CSLA), responsible for acquisition, distribution, and logistics of communications security materiel.[59] The U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) also maintains presence for advanced skills training and linguist support.[59] These organizations collectively support Fort Huachuca's role in intelligence, electronic warfare, and testing missions.[8]Training and Education Programs

The U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence (USAICoE), headquartered at Fort Huachuca, is the Army's primary institution for developing military intelligence (MI) professionals through comprehensive training programs.[36] It focuses on preparing personnel for large-scale combat operations by integrating doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, education, personnel, facilities, and policy to advance the Intelligence Warfighting Function.[36] These programs train enlisted soldiers, warrant officers, and commissioned officers in core MI disciplines, including intelligence analysis, human intelligence collection, counterintelligence, and signals intelligence support.[36] The USAICoE oversees resident and non-resident courses tailored to various ranks and military occupational specialties (MOS). For noncommissioned officers, the Noncommissioned Officer Academy (NCOA) delivers advanced and senior-level professional military education, such as the Advanced Leader Course (ALC) and Senior Leader Course (SLC).[62] MOS-specific training includes the 35T Military Intelligence Systems Maintainer/Integrator ALC, a 40-day performance-based course emphasizing hands-on maintenance and integration of intelligence systems.[62] Officer training features programs like the Military Intelligence Basic Officer Leader Course (MIBOLC), which introduces foundational MI principles and operational planning.[63] Specialized initiatives enhance practical skills and adaptability, including the Threat Immersion Program under the 111th Military Intelligence Brigade, which uses hands-on scenarios and digital simulations to familiarize soldiers with real-world adversary tactics.[64] Additional educational resources, such as the Define & Design Your Success (D2YS) mentorship program for MI leaders and access to the LandWarNet eUniversity's extensive library of over 40,000 cyber, signal, and mission command training aids, support ongoing professional development.[36] The Army Continuing Education System (ACES) at Fort Huachuca further promotes lifelong learning for soldiers and civilians through flexible credentialing and skills programs.[65]