Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Free and open-source graphics device driver

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A free and open-source graphics device driver is a software stack which controls computer-graphics hardware and supports graphics-rendering application programming interfaces (APIs) and is released under a free and open-source software license. Graphics device drivers are written for specific hardware to work within a specific operating system kernel and to support a range of APIs used by applications to access the graphics hardware. They may also control output to the display if the display driver is part of the graphics hardware. Most free and open-source graphics device drivers are developed by the Mesa project. The driver is made up of a compiler, a rendering API, and software which manages access to the graphics hardware.

Drivers without freely (and legally) available source code are commonly known as binary drivers. Binary drivers used in the context of operating systems that are prone to ongoing development and change (such as Linux) create problems for end users and package maintainers. These problems, which affect system stability, security and performance, are the main reason for the independent development of free and open-source drivers. When no technical documentation is available, an understanding of the underlying hardware is often gained by clean-room reverse engineering. Based on this understanding, device drivers may be written and legally published under any software license.

In rare cases, a manufacturer's driver source code is available on the Internet without a free license. This means that the code can be studied and altered for personal use, but the altered (and usually the original) source code cannot be freely distributed. Solutions to bugs in the driver cannot be easily shared in the form of modified versions of the driver. Therefore, the utility of such drivers is significantly reduced in comparison to free and open-source drivers.

Problems with proprietary drivers

[edit]Software developer's view

[edit]

There are objections to binary-only drivers based on copyright, security, reliability and development concerns. As part of a wider campaign against binary blobs, OpenBSD lead developer Theo de Raadt said that with a binary driver there is "no way to fix it when it breaks (and it will break)"; when a product which relies on binary drivers is declared to be end-of-life by the manufacturer, it is effectively "broken forever."[1] The project has also stated that binary drivers[2] "hide bugs and workarounds for bugs",[3] an observation which has been somewhat vindicated by flaws found in binary drivers (including an exploitable bug in Nvidia's 3D drivers discovered in October 2006 by Rapid7). It is speculated that the bug has existed since 2004; Nvidia has denied this, asserting that the issue was only communicated to them in July 2006 and the 2004 bug was a bug in X.Org (not in Nvidia's driver).[4]

Binary drivers often do not work with current versions of open-source software, and rarely support development snapshots of open-source software; it is usually not directly possible for a developer to use Nvidia's or ATI's proprietary drivers with a development snapshot of an X server or a development snapshot of the Linux kernel. Features like kernel mode-setting cannot be added to binary drivers by anyone but the vendors, which prevents their inclusion if the vendor lacks capacity or interest.

In the Linux kernel development community, Linus Torvalds has made strong statements on the issue of binary-only modules: "I refuse to even consider tying my hands over some binary-only module ... I want people to know that when they use binary-only modules, it's their problem".[5] Another kernel developer, Greg Kroah-Hartman, has said that a binary-only kernel module does not comply with the kernel's license (the GNU General Public License); it "just violates the GPL due to fun things like derivative works and linking and other stuff."[6] Writer and computer scientist Peter Gutmann has expressed concern that the digital rights management scheme in Microsoft's Windows Vista operating system may limit the availability of the documentation required to write open drivers, since it "requires that the operational details of the device be kept confidential."[7]

In the case of binary drivers, there are objections due to free software philosophy, software quality and security concerns.[8] In 2006, Greg Kroah-Hartman concluded that:

Closed source Linux kernel modules are illegal. That's it, it is very simple. I've had the misfortune of talking to a lot of different IP lawyers over the years about this topic, and every one that I've talked to all agree that there is no way that anyone can create a Linux kernel module, today, that can be closed source. It just violates the GPL due to fun things like derivative works and linking.[9]

The Linux kernel has never maintained a stable in-kernel application binary interface.[10] There are also concerns that proprietary drivers may contain backdoors, like the one found in Samsung Galaxy-series modem drivers.[11]

Hardware developer's view

[edit]

When applications such as a 3D game engine or a 3D computer graphics software shunt calculations from the CPU to the GPU, they usually use a special-purpose API like OpenGL or Direct3D and do not address the hardware directly. Because all translation (from API calls to GPU opcodes) is done by the device driver, it contains specialized knowledge and is an object of optimization. Due to the history of the rigidity of proprietary driver development there has been a recent surge in the number of community-backed device drivers for desktop and mobile GPUs. Free and Open Hardware organizations like FOSSi, LowRISC, and others, would also benefit from the development of an open graphical hardware standard. This would then provide computer manufacturers, hobbyists, and the like with a complete, royalty-free platform with which to develop computing hardware and related devices.

The desktop computer market was long dominated by PC hardware using the x86/x86-64 instruction set and GPUs available for the PC. With three major competitors (Nvidia, AMD and Intel). The main competing factor was the price of hardware and raw performance in 3D computer games, which is greatly affected by the efficient translation of API calls into GPU opcodes. The display driver and the video decoder are inherent parts of the graphics card: hardware designed to assist in the calculations necessary for the decoding of video streams. As the market for PC hardware has dwindled, it seems unlikely that new competitors will enter this market and it is unclear how much more knowledge one company could gain by seeing the source code of other companies' drivers.

The mobile sector presents a different situation. The functional blocks (the application-specific integrated circuit display driver, 2D and 3D acceleration and video decoding and encoding) are separate semiconductor intellectual property (SIP) blocks on the chip, since hardware devices vary substantially; some portable media players require a display driver that accelerates video decoding, but does not require 3D acceleration. The development goal is not only raw 3D performance, but system integration, power consumption and 2D capabilities. There is also an approach which abandons the traditional method (Vsync) of updating the display and makes better use of sample and hold technology to lower power consumption.

During the second quarter of 2013 79.3% of smartphones sold worldwide were running a version of Android,[12] and the Linux kernel dominates smartphones. Hardware developers have an incentive to deliver Linux drivers for their hardware but, due to competition, no incentive to make these drivers free and open-source. Additional problems are the Android-specific augmentations to the Linux kernel which have not been accepted in mainline, such as the Atomic Display Framework (ADF).[13] ADF is a feature of 3.10 AOSP kernels which provides a dma-buf-centric framework between Android's hwcomposer HAL and the kernel driver. ADF significantly overlaps with the DRM-KMS framework. ADF has not been accepted into mainline, but a different set of solutions addressing the same problems (known as atomic mode setting) is under development. Projects such as libhybris harness Android device drivers to run on Linux platforms other than Android.

Software architecture

[edit]

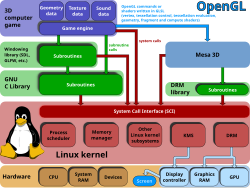

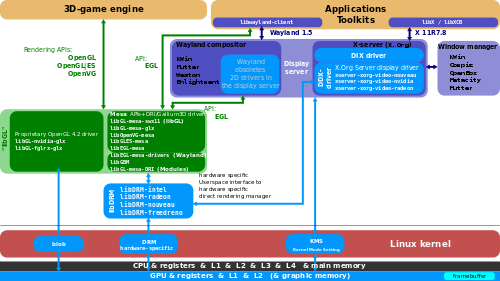

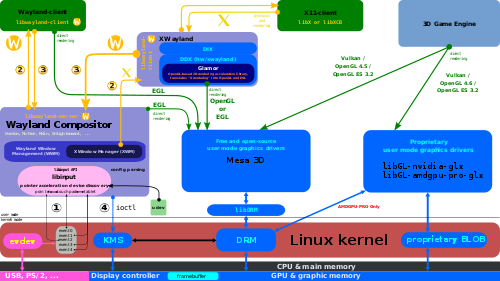

Free and open-source drivers are primarily developed on and for Linux by Linux kernel developers, third-party programming enthusiasts and employees of companies such as Advanced Micro Devices. Each driver has five parts:

- A Linux kernel component DRM

- A Linux kernel component KMS driver (the display controller driver)

- A libDRM user-space component (a wrapper library for DRM system calls, which should only be used by Mesa 3D)

- A Mesa 3D user-space component. This component is hardware-specific; it is executed on the CPU and translates OpenGL commands, for example, into machine code for the GPU. Because the device driver is split, marshalling is possible. Mesa 3D is the only free and open-source implementation of OpenGL, OpenGL ES, OpenVG, GLX, EGL and OpenCL. In July 2014, most of the components conformed to Gallium3D specifications. A fully functional State Tracker for Direct3D version 9 is written in C, and an unmaintained tracker for Direct3D versions 10 and 11 is written in C++.[14] Wine has Direct3D version 9. Another Wine component translates Direct3D calls into OpenGL calls, working with OpenGL.

- Device Dependent X (DDX), another 2D graphics device driver for X.Org Server

The DRM is kernel-specific. A VESA driver is generally available for any operating system. The VESA driver supports most graphics cards without acceleration and at display resolutions limited to a set programmed in the Video BIOS by the manufacturer.[15]

History

[edit]The Linux graphics stack has evolved, detoured by the X Window System core protocol.

-

2D drivers in the X server

-

All access goes through the Direct Rendering Manager

-

In Linux kernel 3.12, render nodes are merged and mode setting split off. Wayland implements direct rendering over EGL.

Free and open-source drivers

[edit]ATI and AMD

[edit]Radeon

[edit]

glxinfo showing OpenGL information with glxgears running on a Linux system with AMDGPU kernel moduleAMD's proprietary driver, AMD Catalyst for their Radeon, is available for Microsoft Windows and Linux (formerly fglrx). A current version can be downloaded from AMD's site, and some Linux distributions contain it in their repositories. It is in the process of being replaced with an AMDGPU-PRO hybrid driver combining the open-source kernel, X and Mesa multimedia drivers with closed-source OpenGL, OpenCL and Vulkan drivers derived from Catalyst.

The FOSS drivers for ATI-AMD GPUs are being developed under the name Radeon (xf86-video-ati or xserver-xorg-video-radeon). They still must load proprietary microcode into the GPU to enable hardware acceleration.[16][failed verification]

Radeon 3D code is split into six drivers, according to GPU technology: the radeon, r200 and r300 classic drivers and r300g, r600g and radeonsi Gallium3D drivers:

- Radeon supports the R100 series.

- R200 supports the R200 series.

- R300g supports pre-unified shader model microarchitectures: R300, R400 and R500.

- R600g supports all TeraScale (VLIW5/4)-based GPUs: R600, R700, HD 5000 (Evergreen) and HD 6000 (Northern Islands).

- Radeonsi supports all Graphics Core Next-based GPUs: HD 7000, HD 8000 and Rx 200 (Southern Islands, Sea Islands and Volcanic Islands).

An up-to-date feature matrix is available,[17] and there is support for Video Coding Engine[18] and Unified Video Decoder.[19][20] The free and open-source Radeon graphics device drivers are not reverse-engineered, but are based on documentation released by AMD without the requirement to sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA).[21][22][23] Documentation began to be gradually released in 2007.[24][25][26]

In addition to providing the necessary documentation, AMD employees contribute code to support their hardware and features.[18]

All components of the Radeon graphics device driver are developed by core contributors and interested parties worldwide. In 2011, the r300g outperformed Catalyst in some cases.

AMDGPU

[edit]At the 2014 Game Developers Conference, AMD announced that they were exploring a strategy change to re-base the user-space part of Catalyst on a free and open-source DRM kernel module instead of their proprietary kernel blob.[27]

The release of the new AMDGPU kernel module and stack was announced on the dri-devel mailing list in April 2015.[28] Although AMDGPU only officially supports GCN 1.2 and later graphics cards,[29] experimental support for GCN 1.0 and 1.1 graphics cards (which are only officially supported by the Radeon driver) may be enabled via a kernel parameter.[30][31] A separate libdrm, libdrm-amdgpu, has been included since libdrm 2.4.63.[32]

The radeonsi 3D code mentioned in the prior Radeon paragraph is also used with amdgpu; the 3D driver has back ends for both radeon and amdgpu.

Nvidia

[edit]

Nvidia's proprietary driver, Nvidia GeForce driver for GeForce, is available for Windows x86/x86-64, Linux x86/x86-64/ARM, OS X 10.5 and later, Solaris x86/x86-64 and FreeBSD x86/x86-64. A current version can be downloaded from the Internet, and some Linux distributions contain it in their repositories. The 4 October 2013 beta Nvidia GeForce driver 331.13 supports the EGL interface, enabling support for Wayland in conjunction with this driver.[33][34]

Nvidia's free and open-source driver is named nv.[35] It is limited (supporting only 2D acceleration), and Matthew Garrett, Dirk Hohndel and others have called its source code confusing.[36][37][38] Nvidia decided to deprecate nv, not adding support for Fermi or later GPUs and DisplayPort, in March 2010.[39]

In December 2009, Nvidia announced they would not support free graphics initiatives.[40] On 23 September 2013, the company announced that they would release some documentation of their GPUs.[41]

Nouveau is based almost entirely on information gained through reverse engineering. This project aims to produce 3D acceleration for X.Org/Wayland using Gallium3D.[42] On March 26, 2012, Nouveau's DRM component was marked stable and promoted from the staging area of the Linux kernel.[43] Nouveau supports Tesla- (and earlier), Fermi-, Kepler- and Maxwell-based GPUs.[44] On 31 January 2014, Nvidia employee Alexandre Courbot committed an extensive patch set which adds initial support for the GK20A (Tegra K1) to Nouveau.[45] In June 2014, Codethink reportedly ran a Wayland-based Weston compositor with Linux kernel 3.15, using EGL and a "100% open-source graphics driver stack" on a Tegra K1.[46] A feature matrix is available.[47] In July 2014, Nouveau was unable to outperform the Nvidia GeForce driver due to missing re-clocking support. Tegra-re is a project which is working to reverse-engineer nVidia's VLIW-based Tegra series of GPUs that predate Tegra K1.[48]

Nvidia distributes proprietary device drivers for Tegra through OEMs and as part of its Linux for Tegra (formerly L4T) development kit.[49] Nvidia and a partner, Avionic Design, were working on submitting Grate (free and open-source drivers for Tegra) upstream of the mainline Linux kernel in April 2012.[50][51] The company's co-founder and CEO laid out the Tegra processor roadmap with Ubuntu Unity at the 2013 GPU Technology Conference.[52]

Nvidia's Unified Memory driver (nvidia-uvm.ko), which implements memory management for Pascal and Volta GPUs on Linux, is MIT licensed. The source code is available in the Nvidia Linux driver downloads on systems that support nvidia-uvm.ko.

In May 2022, Nvidia announced a new initiative and policy to open source its GPU Loadable Kernel Modules with dual GPL–MIT License, but only new models at alpha quality. But said "These changes are for the kernel modules, while the user-mode components are untouched. The user-mode remains closed source and is published with prebuilt binaries in the driver and the CUDA toolkit."[53] The open source driver has since been upgraded to production status and is now officially recommended for the RTX 20 series and later GPUs.[54][55] Blackwell (RTX 50 generation) and later NVIDIA GPU architectures are only supported by the open driver.[56]

Intel

[edit]Intel has a history of producing (or commissioning) open-source drivers for its graphics chips, with the exception of their PowerVR-based chips.[57] Their 2D X.Org driver is called xf86-video-intel. The kernel mode-setting driver in the Linux kernel does not use the video BIOS for switching video modes; since some BIOSes have a limited range of modes, this provides more reliable access to those supported by Intel video adapters.

The company worked on optimizing their free Linux drivers for performance approaching their Windows counterparts, especially on Sandy Bridge and newer hardware where performance optimizations have allowed the Intel driver to outperform their proprietary Windows drivers in certain tasks, in 2011.[58][59][60] Some of the performance enhancements may also benefit users of older hardware.[61]

Support for Intel's LLC (Last Level Cache, L4-Cache, Crystalwell and Iris Pro) was added in Linux kernel 3.12.[62][63] In 2013, the company had 20 to 30 full-time Linux graphics developers.[64]

Matrox

[edit]Matrox develops and manufactures the Matrox Mystique, Parhelia, G200, G400 and G550. Although the company provides free and open-source drivers for their chipsets which are older than the G550; chipsets newer than the G550 are supported by a closed-source driver.

S3 Graphics

[edit]S3 Graphics develops the S3 Trio, ViRGE, Savage and Chrome, supported by OpenChrome.[65]

Arm Ltd

[edit]Arm Ltd is a fabless semiconductor company which licenses semiconductor intellectual property cores. Although they are known for the licensing the ARM instruction set and CPUs based on it, they also develop and license the Mali series of GPUs, and more recently Imortalis GPUs that support ray-tracing. On January 21, 2012, Phoronix reported that Luc Verhaegen was driving a reverse-engineering attempt aimed at the Arm Mali series of GPUs (specifically, the Mali-200 and Mali-400 versions). The reverse-engineering project, known as Lima, was presented at FOSDEM on February 4, 2012.[66][67] On February 2, 2013, Verhaegen demonstrated Quake III Arena in timedemo mode, running on top of the Lima driver.[68] In May 2018, a Lima developer posted the driver for inclusion in the Linux kernel.[69] As of May 2019, the Lima driver is part of the mainline Linux kernel.[70]

Panfrost is a reverse-engineered driver effort for Mali Txxx (Midgard) and Gxx (Bifrost) GPUs. Introducing Panfrost talk was presented at X.Org Developer's Conference 2018. As of May 2019, the Panfrost driver is part of the mainline Linux kernel.[71]

ARM has indicated no intention of providing support for their graphics acceleration hardware licensed under a free and open-source license. However, ARM employees sent patches for the Linux kernel to support their ARM HDLCD display controller and Mali DP500, DP550 and DP650 SIP blocks in December 2015 and April 2016.[72][73]

Imagination Technologies

[edit]Imagination Technologies is a fabless semiconductor company which develops and licenses semiconductor intellectual property cores, among which are the PowerVR GPUs. Intel has manufactured a number of PowerVR-based GPUs. PowerVR GPUs are widely used in mobile system on a chip (SoC) devices. Due to its wide use in embedded devices, the Free Software Foundation has put reverse-engineering of the PowerVR driver on its high-priority project list.[74] As of March 2022, Imagination has provided a FOSS driver for its Rogue architecture-based PowerVR GX6250 from 2014, and its more recent A-Series architecture-based AXE-1-16M and BXS-4-64 GPUs.[75]

Vivante

[edit]Vivante Corporation is a fabless semiconductor company which licenses semiconductor intellectual property cores and develops the GCxxxx series of GPUs. A Vivante proprietary, closed-source Linux driver consists of kernel- and user-space parts. Although the kernel component is open-source (GPL), the user-space components—consisting of the GLES(2) implementations and a HAL library—are not; these contain the bulk of the driver logic.

Wladimir J. van der Laan found and documented the state bits, command stream and shader ISA by studying how the blobs work, examining and manipulating command-stream dumps. The Etnaviv Gallium3D driver is being written based on this documentation. Van der Laan's work was inspired by the Lima driver, and the project has produced a functional-but-unoptimized Gallium3D LLVM driver. The Etnaviv driver has performed better than Vivante's proprietary code in some benchmarks, and it supports Vivante's GC400, GC800, GC1000, GC2000, GC3000 and GC7000 series.[76] In January 2017, Etnaviv was added to Mesa with both OpenGL ES 2.0 and Desktop OpenGL 2.1 support.[77]

Qualcomm

[edit]Qualcomm develops the Adreno (formerly ATI Imageon) mobile GPU series, and includes it as part of their Snapdragon mobile SoC series. Phoronix and Slashdot reported in 2012 that Rob Clark, inspired by the Lima driver, was working on reverse-engineering drivers for the Adreno GPU series.[78][79] In a referenced blog post, Clark wrote that he was doing the project in his spare time and that the Qualcomm platform was his only viable target for working on open 3D graphics. His employers (Texas Instruments and Linaro) were affiliated with the Imagination PowerVR and ARM Mali cores, which would have been his primary targets; he had working command streams for 2D support, and 3D commands seemed to have the same characteristics.[80] The driver code was published on Gitorious "freedreno",[81] and has been moved to Mesa.[82][83] In 2012, a working shader assembler was completed;[84] demonstration versions were developed for texture mapping[85] and phong shading,[86] using the reverse-engineered shader compiler. Clark demonstrated Freedreno running desktop compositing, the XBMC media player and Quake III Arena at FOSDEM on February 2, 2013.[87]

In August 2013, the kernel component of freedreno (MSM driver) was accepted into mainline and is available in Linux kernel 3.12 and later.[88] The DDX driver gained support for server-managed file descriptors requiring X.Org Server version 1.16 and above in July 2014.[89] In January 2016, the Mesa Gallium3D-style driver gained support for Adreno 430;[90] in November of that year, the driver added support for the Adreno 500 series.[91] Freedreno can be used on devices such as 96Boards Dragonboard 410c and Nexus 7 (2013) in traditional Linux distributions (like Debian and Fedora) and on Android.

Broadcom

[edit]

Broadcom develops and designs the VideoCore GPU series as part of their SoCs. Since it is used by the Raspberry Pi, there has been considerable interest in a FOSS driver for VideoCore.[93] The Raspberry Pi Foundation, in co-operation with Broadcom, announced on October 24, 2012, that they open-sourced "all the ARM (CPU) code that drives the GPU".[citation needed] However, the announcement was misleading; according to the author of the reverse-engineered Lima driver, the newly open-sourced components only allowed message-passing between the ARM CPU and VideoCore but offered little insight into Videocore and little additional programability.[94] The Videocore GPU runs an RTOS which handles the processing; video acceleration is done with RTOS firmware coded for its proprietary GPU, and the firmware was not open-sourced on that date.[95] Since there was neither a toolchain targeting the proprietary GPU nor a documented instruction set, no advantage could be taken if the firmware source code became available. The Videocoreiv project[96] attempted to document the VideoCore GPUs.

On February 28, 2014 (the Raspberry Pi's second anniversary), Broadcom and the Raspberry Pi Foundation announced the release of full documentation for the VideoCore IV graphics core and a complete source release of the graphics stack under a 3-clause BSD license.[97][98] The free-license 3D graphics code was committed to Mesa on 29 August 2014,[99] and first appeared on Mesa's 10.3 release.

Other vendors

[edit]Although Silicon Integrated Systems and VIA Technologies have expressed limited interest in open-source drivers, both have released source code which has been integrated into X.Org by FOSS developers.[38] In July 2008, VIA opened documentation of their products to improve its image in the Linux and open-source communities.[100] The company has failed to work with the open-source community to provide documentation and a working DRM driver, leaving expectations of Linux support unfulfilled.[101] On January 6, 2011, it was announced that VIA was no longer interested in supporting free graphics initiatives.[102]

DisplayLink announced an open-source project, Libdlo,[103] with the goal of bringing support for their USB graphics technology to Linux and other platforms. Its code is available under the LGPL license,[104] but it has not been integrated into an X.Org driver. DisplayLink graphics support is available through the kernel udlfb driver (with fbdev) in mainline and udl/drm driver, which in March 2012 was only available in the drm-next tree.

Non-hardware-related vendors may also assist free graphics initiatives. Red Hat has two full-time employees (David Airlie and Jérôme Glisse) working on Radeon software,[105] and the Fedora Project sponsors a Fedora Graphics Test Week event before the launch of their new Linux distribution versions to test free graphics drivers.[106] Other companies which have provided development or support include Novell and VMware.

Open hardware projects

[edit]

Project VGA aims to create a low-budget, open-source VGA-compatible video card.[107] The Open Graphics Project aimed to create an open-hardware GPU. In September 2010, the first 25 OGD1 boards were made available for grant application and purchase.[108] The Milkymist system on a chip, targeted at embedded graphics instead of desktop computers, supports a VGA output, a limited vertex shader and a 2D texturing unit.[109]

The Nyuzi,[110] an experimental GPGPU processor, includes a synthesizable hardware design written in System Verilog, an instruction set emulator, an LLVM-based C-C++ compiler, software libraries and tests and explores parallel software and hardware. It can run on a Terasic DE2-115 field-programmable gate array board.[111][112]

If a project uses FPGAs, it generally has a partially (or completely) closed-source toolchain. There are currently a couple of open-source toolchains available, however, for Lattice-based FPGAs (notably for iCE40 and ECP5 boards) which utilize Project IceStorm,[113] and Trellis,[114] respectively. There is also a larger, ongoing effort to create the "GCC of FPGAs" called SymbiFlow[115] which includes the aforementioned FPGA toolchains as well as an early-stage open-source toolchain for Xilinx-based FPGAs.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ de Raadt, Theo (2006-12-03). "Open Documentation for Hardware". Presentation slides from OpenCON 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ^ "What does "binary" means in device driver?". Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ "3.9: "Blob!"". OpenBSD. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ "Linux - How does the Rapid7 Advisory R7-0025 affect the NVIDIA Unix driver?".

- ^ "a/lt-binary".

- ^ Kroah-Hartman, Greg. "Myths, Lies, and Truths about the Linux kernel". linux kernel monkey log.

- ^ Gutmann, Peter (2006-12-26). "A Cost Analysis of Windows Vista Content Protection". Retrieved 2007-01-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Linux Weekly News, Aug 14, 2006: X.org, distributors, and proprietary modules

- ^ Kroah-Hartman, Greg (2006). "Myths, Lies, and Truths about the Linux kernel". Linux Symposium.

- ^ "The Linux Kernel Driver Interface". Archived from the original on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2014-03-04.

- ^ "SamsungGalaxyBackdoor". 2014-02-04.

- ^ "Android Nears 80% Market Share In Global Smartphone Shipments, As iOS And BlackBerry Share Slides, Per IDC". 7 August 2013.

- ^ "Atomic Display Framework".

- ^ "Direct3D 9 state tracker". 16 July 2013. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ "Index of /doc/Documentation/fb/". Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Details of Debian package firmware-linux-nonfree in Stable Debian.org

- ^ "Radeon Feature". Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ a b "initial VCE support in Linux kernel and in the Mesa driver". 4 February 2014.

- ^ "drm-next-3.15 Feb 18". 18 February 2014.

- ^ "drm-next-3.15 Mar 04". 4 March 2014.

- ^ "AMD Developer Guides". Archived from the original on 2013-07-16.

- ^ "Documentation provided by AMD".

- ^ "AMD 3D Documentation list". Archived from the original on 2013-10-07.

- ^ "AMD to open up graphics specs". LWN.net. 2007-09-05. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "AMD: GPU Specifications Without NDAs!". 2007-09-10. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ Airlie, David (2007-09-13). "AMD hand me specs on a CD". Archived from the original on 2012-10-22. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "AMD exploring new Linux driver Strategy". 2014-03-22. Retrieved 2014-03-23.

- ^ "Initial AMDGPU driver release". 2015-04-20. Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- ^ "AMD Moves Forward With Unified Linux Driver Strategy, New Kernel Driver". Phoronix.

- ^ "AMDGPU driver documentation". Freedesktop.org.

- ^ "AMD Unleashes Initial AMDGPU Driver Support For GCN 1.0 / Southern Islands GPUs". Phoronix.

- ^ "libdrm 2.4.63". 2015-08-14.

- ^ "Support for EGL on 32-bit platforms". 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "lib32-nvidia-utils 340.24-1 File List". 2014-07-15.

- ^ "X.org nv driver page". 2013-05-20.

- ^ "Patch by Dirk Hohndel". 1998-11-18. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

... opposed to such obfuscated code. We do not regard this as free software according to our standards

- ^ "Nouveau: The community & past, current and future developments" (PDF). 2011-09-13. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ a b Airlie, David M. (2006-07-19). "Open Source Graphic Drivers: They Don't Kill Kittens" (PDF). Proceedings of the Linux Symposium Volume One. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ^ "Nvidia deprecates "NV"". Phoronix. 2010-03-26.

- ^ "Nvidia's Response To Recent Nouveau Work". Phoronix. 2009-12-14.

- ^ "Nvidia offers to release public documentation on certain aspects of their GPUs". 2013-09-23. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ^ "Nouveau: Accelerated Open Source driver for nVidia cards". Archived from the original on 2014-07-23. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ^ "The Nouveau driver graduates from staging". LWN.net. 2012-03-23.

- ^ "Engineering names for Nvidia".

- ^ "drm/nouveau: initial support for GK20A (Tegra K1)". 2014-01-31.

- ^ "Codethink Gets The NVIDIA Jetson TK1 Running With Linux 3.15, Wayland". Phoronix. 2014-06-12.

- ^ "Nouveau Driver Feature Matrix". Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "Tegra-re". GitHub. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "Linux For Tegra Archive". 30 January 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ Mayo, Jon (2012-04-20). "[RFC 0/4] Add NVIDIA Tegra DRM support". dri-devel (Mailing list). Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (2012-04-11). "A NVIDIA Tegra 2 DRM/KMS Driver Tips Up". Phoronix Media. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ^ "GTC 2013: NVIDIA's Tegra Roadmap (6 of 11)". YouTube. 19 March 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- ^ "NVIDIA Releases Open-Source GPU Kernel Modules". 2022-05-19. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ "NVIDIA 560 Linux Driver Beta Released - Defaults To Open GPU Kernel Modules". www.phoronix.com. Retrieved 2025-04-04.

- ^ "NVIDIA Promotes Their Open-Source GPU Kernel Driver Support". www.phoronix.com. Retrieved 2025-04-04.

- ^ "Chapter 44. Open Linux Kernel Modules". download.nvidia.com. Retrieved 2025-05-10.

- ^ An overview of graphic card manufacturers and how well they work with Ubuntu Ubuntu Gamer, January 10, 2011 (Article by Luke Benstead); (copy of the article)

- ^ "More Performance Comes Out Of Intel Linux SNB". Phoronix. 2011-03-22. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ "Intel Sandy Bridge Performance Goes Up Again". Phoronix. 2011-03-31. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- ^ "Intel SNB Linux Driver Can Out Run Windows Driver". Phoronix. 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ^ "A Historical Look At Intel Ironlake Graphics Performance". Phoronix. 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ^ "drm/i915: Use eLLC/LLC by default when available".

- ^ "drm/i915: Use Write-Through cacheing for the display plane on Iris".

- ^ "Intel Has 20~30 Full-Time Linux Graphics Developers". 2013-02-02.

- ^ "OpenChrome". Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ phoronix (6 February 2012). "Phoronix.com - FOSDEM 2012 - Open-Source ARM Mali". Archived from the original on 2021-12-21 – via YouTube.

- ^ Phoronix, Jan 21 2012: An Open-Source, Reverse-Engineered Mali GPU Driver

- ^ "Quake 3 Arena timedemo on top of the lima driver!". Archived from the original on 2013-02-09.

- ^ "Lima DRM driver [LWN.net]". lwn.net.

- ^ drm/lima: driver for ARM Mali4xx GPUs}

- ^ drm/panfrost: Add initial panfrost driver

- ^ "drm: Add support for the ARM HDLCD display controller". Linux kernel mailing list. 2015-12-11.

- ^ "Initial support for ARM Mali Display Controller". Linux kernel mailing list. 2016-04-01.

- ^ Free Software Foundation, Apr 25, 2005: High Priority Free Software Projects

- ^ "Imagination Tech Publishes Open-Source PowerVR Vulkan Driver For Mesa". www.phoronix.com. Retrieved 2022-04-19.

- ^ "laanwj/etna_viv". GitHub.

- ^ "etnaviv: gallium driver for Vivante GPUs".

- ^ Larabel, Michael (14 April 2012). "An Open-Source Graphics Driver for Snapdragon". Phoronix. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Soulskill (14 April 2012). "Open-Source Qualcomm GPU Driver Published". Slashdot. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Clark, Rob (14 April 2012). "Fighting back against binary blobs!". Linaro. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Freedreno, 15 April 2012 Archived 24 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mesa/Gallium3D Gets Its First ARM SoC GPU Driver - Phoronix".

- ^ "Mesa (master): r600g: add Richland APU pci ids". 15 March 2013.

- ^ Clark, Rob (29 July 2012). "freedreno update: first renders shader assembler!". Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ Clark, Rob (5 August 2012). "textured cube (fullscreen!)". Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ Clark, Rob (15 August 2012). "Open Source lolscat!". Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ "Open ARM GPU drivers – Freedreno". FOSDEM. 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ^ "Merge the MSM driver from Rob Clark". kernel.org. 2013-08-28. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ^ "xf86-video-freedreno 1.2.0". freedesktop.org. 2014-07-14.

- ^ "Add support for adreno 430". Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ "Index Mesa-Mesa". Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Anholt, Eric (2014-06-17). "New Job at Broadcom". Archived from the original on 2015-04-07.

- ^ "Phoronix on the Raspberry Pi GPU".

- ^ "Open Source ARM userland - Raspberry Pi". 24 October 2012.

- ^ "Open Source ARM userland - Raspberry Pi". 24 October 2012. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ "hermanhermitage/videocoreiv". GitHub.

- ^ "Raspberry Pi marks 2nd birthday with plan for open source graphics driver". 28 February 2014.

- ^ Upton, Eben (28 February 2014). "A birthday present from Broadcom - Raspberry Pi". Raspberry Pi Foundation. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ "vc4: Initial skeleton driver import". The Mesa 3D Graphics Library. 2014-08-09.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (2008-07-26). "VIA Publishes Three Programming Guides". Phoronix. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (2009-11-21). "VIA's Linux TODO List... Maybe Look Forward To 2011?". Phoronix. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ^ VIA's Open Linux Graphics Driver Has Been Defenestrated Phoronix, January 06, 2011 (article by Michael Larabel)

- ^ "Libdlo". Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "DisplayLink Releases Linux Source Code for its USB Graphics Processors" (Press release). DisplayLink. 2009-05-15. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ AMD's Hiring Another Open-Source Driver Developer Phoronix, December 11, 2010 (article by Michael Larabel)

- ^ It's Fedora Graphics Test Week Phoronix, February 22, 2011 (article by Michael Larabel)

- ^ "Home of Project VGA, the low budget, open source, VGA compatible video card". 090503 wacco.mveas.com

- ^ "Linux Fund: OGD1". Open Graphics Project. 2010-09-23. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ^ Bourdeauducq, Sebastien (June 2010). "A performance-driven SoC architecture for video synthesis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2010-11-05.

- ^ "Nyuzi is an experimental GPGPU processor". GitHub. June 2021.

- ^ "SOC Test Environment". GitHub.

- ^ "Running on Terasic DE2-115 FPGA board". GitHub.

- ^ "Project IceStorm Homepage". 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Project Trellis Repository". GitHub. 30 May 2021.

- ^ "SymbiFlow Homepage".

External links

[edit]- Linux graphics drivers from Intel

- Best Graphics Card For Linux Archived 2017-03-25 at the Wayback Machine

- NVIDIA's Unix drivers portal page

- Project VGA

- Direct3D 9 state tracker on Gallium3D

- d3d1x: add new Direct3D 10/11 COM state tracker for Gallium

- Freedreno on GitHub

- Freedreno/Gallium update

- Phoronix Test Suite

- Status updates for three graphics drivers (Nouveau, amdgpu and Etnaviv) LWN.net 2015

Free and open-source graphics device driver

View on GrokipediaOverview and Fundamentals

Definition and Core Components

A free and open-source graphics device driver is a modular software stack licensed under permissive terms such as the GNU General Public License or MIT License, designed to control graphics hardware and enable rendering of 2D and 3D content via standardized application programming interfaces (APIs) like OpenGL and Vulkan. These drivers bridge the operating system kernel and user-space applications to the graphics processing unit (GPU), managing hardware resources including memory allocation, command submission, and synchronization to achieve accelerated performance.[2][8] The core architecture divides into kernel-space and user-space layers for security and efficiency. In the kernel space, the Direct Rendering Manager (DRM) serves as the foundational subsystem in Linux, providing a unified interface for GPU access, modesetting (configuring display outputs), and buffer management while enforcing isolation between processes. DRM incorporates memory management frameworks such as the Graphics Execution Manager (GEM), which handles virtual memory objects for GPU buffers, or the Translation Table Manager (TTM), which supports unified memory architectures across CPU and GPU domains.[9][10][11] User-space components, exemplified by the Mesa 3D Graphics Library, implement the rendering APIs and translate them into hardware-specific operations, supporting both vendor-backed drivers (e.g., AMD's RadeonSI, Intel's ANV) and community-developed ones (e.g., Nouveau for NVIDIA GPUs). Mesa integrates with kernel drivers via mechanisms like the Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI), allowing direct GPU access from user applications while leveraging modular frameworks such as Gallium3D to decouple API state tracking from low-level hardware drivers, enhancing portability across GPU architectures.[2][12] This separation enables software fallbacks like LLVMpipe for rendering without hardware acceleration when native drivers are incomplete.[2]Role in Graphics Rendering Pipelines

Free and open-source graphics device drivers integrate into graphics rendering pipelines by providing the interface between application-level graphics APIs and GPU hardware execution. The rendering pipeline consists of sequential stages including vertex processing, primitive assembly, rasterization, fragment shading, and per-sample operations, culminating in framebuffer output. These drivers, particularly in open ecosystems like Linux, enable hardware-accelerated execution of these stages by translating high-level commands into low-level GPU instructions.[13] In user-space, libraries such as Mesa implement APIs like OpenGL and Vulkan, managing state tracking, shader compilation from languages like GLSL to intermediate representations, and resource allocation for buffers and textures. Mesa drivers convert API calls into device-specific commands, interfacing with the kernel through the Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI). This allows applications to submit rendering commands directly to the GPU, minimizing CPU involvement and supporting efficient pipeline traversal on supported hardware.[12][1] Kernel-level components, governed by the Direct Rendering Manager (DRM), handle device initialization, memory management via subsystems like GEM or TTM, command queue maintenance, and DMA-based submission to the GPU. FOSS drivers ensure secure, shared access to graphics resources across processes, facilitating synchronization and context switching essential for multi-application rendering environments. This architecture underpins direct rendering, where GPU pipelines process 3D scenes in real-time, as opposed to software emulation, though completeness depends on hardware documentation availability.[13][1]Historical Evolution

Pre-2000s Foundations

The Linux kernel, first released as version 0.01 on September 17, 1991, incorporated open-source drivers for VGA-compatible graphics hardware from its outset, primarily through the vgacon console driver, which supported text-mode output with color attributes on IBM PC-compatible systems. These foundational drivers handled basic display operations via direct port I/O and memory-mapped VGA registers, enabling reliable console functionality without proprietary dependencies. In April 1992, the XFree86 project was established by David Wexelblat, David Dawes, Glenn Lai, and Jim Tsillas to develop a freely redistributable X Window System server optimized for Intel x86 platforms, including modular device drivers for 2D graphics acceleration. Early XFree86 versions supported hardware such as the Tseng ET4000, Cirrus Logic GD542x, and S3 86x/92x chipsets, with drivers relying on community reverse engineering of undocumented interfaces to achieve bit-block transfers and mode setting. This effort addressed the absence of official open-source support from vendors, fostering graphical desktops on Linux and BSD systems by the mid-1990s.[14] Concurrently, Brian Paul launched the Mesa 3D graphics library in August 1993 as an open-source software renderer implementing the OpenGL 1.0 specification, initially without hardware acceleration to ensure portability across platforms. Mesa's rasterization engine, written in C, provided a foundation for 3D rendering in applications, integrating with XFree86 via the GLX extension for off-screen rendering and basic scene display.[15] The Linux framebuffer device subsystem emerged in experimental form during kernel 2.1.x development around 1997–1998, formalizing abstraction for graphics hardware in version 2.2, which allowed user-space access to frame buffers for console graphics and simple acceleration on VGA and early PCI adapters. This kernel-level interface complemented XFree86 servers, enabling boot-time graphical consoles and paving the way for unified driver models.[16]2000s: Reverse Engineering and Mesa Advancements

In the early 2000s, free and open-source graphics drivers for consumer GPUs advanced primarily through community-driven reverse engineering of proprietary hardware from vendors like NVIDIA and ATI, who withheld detailed specifications to protect intellectual property.[17] These efforts targeted undocumented registers, command streams, and firmware behaviors, often using tools like hardware probes and binary disassembly, as kernel-level access to GPUs remained limited without vendor cooperation.[18] By mid-decade, projects achieved basic 2D acceleration and partial 3D support, though performance lagged proprietary drivers due to incomplete reverse engineering and power management gaps.[17] The Nouveau project exemplified these initiatives for NVIDIA hardware, originating in 2005 as patches extending the rudimentary "nv" driver and publicly unveiled at FOSDEM in February 2006.[19] Developers, led by Stéphane Marchesin, systematically documented NVIDIA chipsets starting with the NV10 series, enabling open kernel modules for memory management and command submission by 2008.[19] For ATI's Radeon lineup, the r300 project reverse-engineered the R300 and R400 GPUs (e.g., Radeon 9700 and X800 series), yielding a Mesa-compatible gallium driver by late 2006 that supported textured rendering and vertex processing, though full shader model 2.0 compliance required further iteration.[18][17] These drivers integrated with the Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI) for user-space acceleration, but reclocking and video decoding often remained proprietary-dependent.[18] Mesa, the foundational open-source implementation of OpenGL and related APIs, underwent architectural evolution to accommodate reverse-engineered backends.[20] Key releases like Mesa 6.5 in 2006 enhanced state tracking and fixed-function pipelines, improving compatibility for early 3D accelerators.[21] The decade's pinnacle was Gallium3D, introduced in 2008 by Tungsten Graphics engineers including Keith Whitwell, which replaced Mesa's monolithic driver model with a modular interface featuring state trackers, TGSI intermediate representation, and pipe drivers for hardware abstraction.[22] This design reduced duplication across drivers—e.g., enabling a single OpenGL state tracker to front multiple gallium backends—and accelerated development for reverse-engineered GPUs like r300g, achieving up to 50% code reuse while supporting emerging features like programmable shaders.[23] Gallium's adoption in Mesa 7.0 (2008) marked a shift toward scalable, vendor-agnostic 3D rendering, though initial implementations prioritized functionality over peak performance on undocumented hardware.[20]2010s-Present: Vendor Open-Sourcing Efforts

AMD advanced its open-source graphics driver development in the 2010s by overhauling the Radeon kernel driver in June 2013, introducing dynamic power management support for GPUs as far back as the Radeon HD 2000 series (R600 architecture, released 2007).[24] This effort built on prior community reverse-engineering, enabling better integration with the Linux kernel's Direct Rendering Manager (DRM) subsystem. In April 2015, AMD upstreamed the amdgpu driver as a replacement for radeon on newer hardware, targeting Graphics Core Next (GCN) architectures starting from Southern Islands (HD 7000 series, 2011) and providing foundational support for features like heterogeneous computing via ROCm.[25] By the late 2010s, AMD's contributions extended to user-space components in Mesa, including the RADV Vulkan driver, fostering improved performance parity with proprietary stacks on platforms like SteamOS.[26] Intel sustained its longstanding commitment to open-source drivers through the i915 kernel module, iteratively adding support for integrated graphics generations throughout the decade, including robust hardware acceleration for Sandy Bridge (2011), Haswell (2013), and Skylake (2015) via enhancements in the Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI).[27] These updates emphasized upstream kernel integration and collaboration with the Mesa project, yielding reliable 3D rendering and video decode capabilities without proprietary blobs, as evidenced by Intel's leading share of Linux graphics kernel contributions by 2020.[26] Intel's approach prioritized empirical validation through public testing and avoided the fragmentation seen in closed ecosystems, enabling widespread adoption in distributions like Fedora and Ubuntu. NVIDIA, historically reliant on proprietary drivers for optimal performance, initiated vendor-led open-sourcing in May 2022 with the release of Linux GPU kernel modules under dual GPL/MIT licenses in the R515 branch, covering core functionality like memory management and compute scheduling for Turing-generation GPUs and later.[28] This marked a departure from the 2010s era, where community-driven Nouveau driver lagged due to limited documentation and reclocking issues. By July 2024, NVIDIA committed to a complete transition to open-source kernel modules, decoupling them from the proprietary user-space components while recommending the open variant for supported hardware starting with the 560 series driver in May 2024. As part of ongoing improvements to the open kernel modules post-2022, a June 2024 commit removed the deprecated "semaphore surface" synchronization mechanism (associated with the callback "__nv_drm_semsurf_wait_fence_work_cb") to simplify the codebase, as it was no longer needed for modern GPUs; this occurred in branches around the R555/R560 series.[28][29][30] Among other vendors, Qualcomm upstreamed an open-source 2D/3D kernel driver for its Adreno GPUs in July 2010, targeting early OpenGL ES acceleration in embedded Linux environments.[31] ARM officially endorsed the community-developed Panfrost driver for Mali GPUs in September 2020, providing blob-free Midgard and Bifrost support and reducing reliance on reverse engineering for Valhall architectures. These efforts, while narrower in scope than desktop vendors, addressed causal dependencies in mobile SoCs by enabling verifiable, modifiable codebases amid rising demand for FOSS in Android and embedded systems.Technical Architecture

Kernel-Level Drivers and Interfaces

Kernel-level drivers in free and open-source graphics systems, particularly within the Linux ecosystem, provide essential low-level hardware abstraction through the Direct Rendering Manager (DRM) subsystem. DRM serves as a device-independent kernel framework that enables secure, direct access to graphics hardware for user-space rendering applications, managing aspects such as DMA transfers, interrupt handling, and resource arbitration.[9] Introduced in the late 1990s and evolved over subsequent kernel releases, DRM mitigates the risks of concurrent hardware access by enforcing locking mechanisms and buffer validation.[32] A foundational feature of DRM is Kernel Mode Setting (KMS), which shifts display configuration—including resolution, refresh rates, and pixel depths—from user-space utilities to the kernel space during boot and runtime.[33] This approach, standardized across open-source drivers since the mid-2000s, eliminates dependencies on proprietary firmware for basic display initialization and supports seamless mode switches without screen blackouts or delays associated with earlier user-space mode-setters like XFree86.[33] KMS integration requires drivers to invokedrmm_mode_config_init() to establish the mode-setting core, which handles connector detection, encoder configuration, and framebuffer management via the kernel's generic framebuffer device (fbdev).[33]

Memory management within DRM relies on two complementary subsystems: the Graphics Execution Manager (GEM) and Translation Table Maps (TTM). GEM, designed for simpler unified memory architectures prevalent in integrated GPUs, offers a lightweight API for buffer object creation, mapping to user or kernel space, and synchronization primitives, with widespread adoption in drivers like Intel's i915 since kernel 2.6.28 in 2008.[34] TTM, an earlier and more versatile manager introduced around 2007, supports complex migration of buffers across system RAM, VRAM, and GART apertures, making it suitable for discrete GPUs in drivers such as AMD's radeon and nouveau; it provides eviction, swapping, and page fault handling for efficient resource utilization under memory pressure.[34] Drivers select one based on hardware needs, with GEM emphasizing code reuse and TTM prioritizing flexibility for non-UMA setups.[34]

Communication between kernel drivers and user-space components occurs via ioctls defined in the DRM API, accessible through libraries like libdrm, which abstract operations such as command buffer submission, fence signaling for synchronization, and GEM/TTM object handles.[35] These interfaces ensure hardware-specific implementations—such as register programming and firmware loading in open-source drivers—conform to a unified contract, enabling portability across Mesa's user-space stack while exposing vendor extensions where necessary.[35] Power management and runtime suspend/resume are also coordinated at this level via DRM's runtime PM framework, integrating with the kernel's broader device model to optimize energy use in mobile and desktop scenarios.[9]

User-Space Libraries and API Implementations

Mesa serves as the central user-space library for free and open-source graphics drivers, implementing graphics APIs including OpenGL up to version 4.6, Vulkan up to 1.4, and OpenGL ES.[12][36] It manages rendering state, compiles shaders to intermediate representations, and generates hardware-specific commands that interface with kernel drivers via the Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI).[12] Mesa's modular design allows hardware vendors to develop targeted drivers while sharing common API translation layers.[2] The Gallium3D framework within Mesa provides a unified architecture for user-space drivers, decoupling API state trackers from hardware-specific code to facilitate multi-API support and portability.[22] Introduced in 2008 by Tungsten Graphics, Gallium3D enables drivers like radeonsi for AMD Radeon GPUs and i915 for Intel to implement OpenGL through a common interface, with subsequent additions for Vulkan via dedicated drivers such as RADV (for AMD, supporting Vulkan 1.3+ since 2016) and ANV (for Intel, initial support in Mesa 12.0 released July 2016).[22][37] API implementations in Mesa include libraries like libGL for desktop OpenGL, libGLES for embedded profiles, and libEGL for platform abstraction, often bundled with extensions for video acceleration such as VA-API.[2] For Vulkan, Mesa's drivers conform to the Khronos specification, with RADV achieving full Vulkan 1.0 validation in 2016 and ongoing extensions for ray tracing via VK_KHR_ray_tracing_pipeline added in later releases.[37][36] Nouveau, the open-source NVIDIA driver, relies on Mesa's Gallium3D for partial OpenGL support through nv50 and nvc0 drivers, though Vulkan implementation (NVK) remains experimental as of 2023.[12] Mesa also supports cross-API translation, such as Zink, a Gallium3D driver that layers OpenGL over Vulkan for hardware lacking native OpenGL but supporting Vulkan, enabling broader compatibility on modern GPUs. These user-space components ensure that applications access standardized APIs without direct hardware dependencies, though performance varies by driver maturity and hardware features.[12]Hardware-Specific Optimizations and Limitations

Hardware-specific optimizations in free and open-source graphics device drivers leverage vendor-provided documentation and firmware to implement features like dynamic clock scaling, power gating, and hardware-accelerated command submission tailored to GPU architectures. For AMD Radeon GPUs using the amdgpu kernel driver, optimizations include user-mode queues that bypass kernel mediation for job submission directly to hardware on Graphics Core Next (GCN) and later architectures, reducing latency in compute workloads.[38] This is enabled for Southern Islands and newer families, with firmware blobs required for full clock and power management on discrete GPUs.[39] Intel's i915 driver, supporting integrated graphics from Gen4 onward, incorporates runtime power management via dynamic enabling and disabling of hardware blocks, such as display pipelines and execution units, to minimize idle power on mobile platforms.[40] Optimizations extend to context isolation for multi-application rendering and partial reconfiguration for efficiency in low-power states, though the driver prioritizes stability over aggressive tuning, with experimental support in the newer Xe driver for Arc and Meteor Lake GPUs showing up to 15-20% performance variance in benchmarks due to incomplete hardware exposure.[41] Limitations persist in reverse-engineered drivers lacking full vendor disclosure. The Nouveau driver for NVIDIA GPUs cannot reliably reclock cores on Fermi and later architectures without unsigned or hacked firmware, confining operation to base clocks that yield 10-50% lower performance in graphics tasks compared to proprietary modules, alongside inefficient power states leading to higher thermal output.[42] For embedded GPUs like ARM Mali Utgard in the Lima driver, optimizations are constrained by incomplete reverse-engineering, omitting advanced tiling and shader features, resulting in software fallbacks for OpenGL ES 2.0 and limited Vulkan conformance.[43] Even vendor-supported drivers face hardware generational cutoffs, as seen with i915 deprecation for pre-Skylake Intel GPUs in kernels post-6.10, forcing users to older branches for legacy support.[44] These gaps stem from causal dependencies on proprietary firmware for secure bootloaders and microcode, which open-source efforts cannot fully replicate without risking hardware instability.Vendor-Specific Implementations

AMD and ATI Drivers

AMD and ATI (acquired by AMD on July 24, 2006) graphics hardware is supported by fully open-source kernel drivers integrated into the mainline Linux kernel, primarily radeon for pre-Graphics Core Next (GCN) architectures and amdgpu for GCN, RDNA, and CDNA designs. The radeon driver handles ATI Radeon R100 through Evergreen series GPUs, providing 2D acceleration, basic 3D rendering via Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI), and power management features developed through community reverse engineering augmented by vendor documentation. In contrast, amdgpu delivers advanced capabilities including hardware-accelerated video decoding (UVD/VCN), compute shaders, and SR-IOV for virtualization on modern Radeon RX series cards.[45] Following the ATI acquisition, AMD launched its open-source graphics initiative in September 2007 by releasing register-level documentation and firmware binaries for the R600 (Radeon HD 2000) series, enabling developers to implement full-featured support without proprietary blobs. This effort transitioned the radeon driver from partial functionality to robust 3D acceleration by 2009, including Gallium3D state trackers in Mesa for OpenGL compliance. However, extending radeon for post-Evergreen hardware proved inefficient due to architectural shifts, prompting AMD to develop amdgpu as a successor. Announced in 2014 and upstreamed to the Linux kernel in 2015, amdgpu initially supported Southern Islands (SI) and Sea Islands (CIK) GCN 1.0/1.1 GPUs experimentally, becoming the default for compatible hardware by kernel 4.7 in 2016.[46][47][48] AMD maintains active upstream contributions through dedicated engineers, ensuring timely integration of firmware updates and hardware enables for new releases like the Radeon RX 7000 series (RDNA 3) as of Linux kernel 6.11 in September 2024. User-space rendering leverages Mesa's radeonsi for OpenGL and RADV for Vulkan, achieving performance within 5-10% of proprietary drivers in benchmarks while supporting extensions like Variable Rate Shading. This model avoids binary blobs for core functionality, though microcode firmware remains proprietary but openly licensed for redistribution. Ongoing developments include enhancements for display clock management (DCN) and reliability (RAS) in kernel 6.13 previews as of October 2025.[49][37][50] The drivers' upstream focus facilitates seamless integration across distributions, with empirical data showing stable operation for desktop, gaming, and compute workloads; for instance, amdgpu enabled full ROCm support for AI training on Radeon GPUs by 2020. Limitations persist for very legacy ATI cards pre-R100, relying on vesafb or minimal fbdev, but AMD's strategy has positioned its GPUs as the most Linux-friendly among discrete vendors, substantiated by adoption rates exceeding 90% in server deployments.[5]NVIDIA Drivers

The primary free and open-source graphics device driver for NVIDIA GPUs on Linux systems is Nouveau, a community-driven project initiated through reverse engineering of NVIDIA hardware interfaces.[4] Development began in the mid-2000s, with initial efforts focused on decoding proprietary firmware and command streams to enable basic 2D and 3D acceleration without official documentation from NVIDIA.[51] Nouveau integrates with the Mesa user-space library for OpenGL and Vulkan support via state trackers like NVK, but its progress has been hampered by the need for ongoing disassembly of closed-source binaries, resulting in incomplete feature parity for newer architectures.[4] Historically, NVIDIA's reluctance to release comprehensive hardware specifications—citing intellectual property protection—forced Nouveau developers to rely on empirical analysis of GPU behavior, leading to challenges in areas such as dynamic clocking (reclocking) and power management.[52] For instance, on Turing and later GPUs, Nouveau often operates at reduced clock speeds without proprietary firmware blobs, limiting performance to 10-50% of proprietary drivers in compute-intensive workloads like gaming or rendering.[53] Benchmarks from 2019 showed Nouveau trailing NVIDIA's closed-source drivers by factors of 2-5x in OpenGL tests on supported hardware, with even greater gaps in Vulkan due to immature NVK implementation.[53] This disparity persists, as proprietary drivers incorporate vendor-specific optimizations unavailable in open-source alternatives.[51] In May 2022, NVIDIA released open-source Linux GPU kernel modules under dual GPL/MIT licensing as part of the R515 driver branch, marking a shift toward partial transparency driven by demands from the Linux ecosystem for better integration with features like explicit sync.[28] By July 2024, NVIDIA fully transitioned production drivers to these open kernel modules for architectures from Volta onward, while maintaining closed-source components for pre-Volta GPUs and user-space libraries.[28] Concurrently, NVIDIA began publishing select hardware interface documentation via the open-gpu-doc repository, aiding reverse-engineering efforts but excluding sensitive firmware details essential for full reclocking.[52] These modules support core DRM (Direct Rendering Manager) functionalities but do not encompass the full driver stack, leaving Nouveau to bridge remaining gaps independently.[30] Despite advancements, Nouveau's limitations in stability and efficiency—such as incomplete Optimus hybrid graphics support and higher power draw—stem from incomplete access to NVIDIA's internal causal models of GPU state machines, perpetuating reliance on proprietary alternatives for high-performance use cases.[4] Community reports indicate that while basic display and acceleration work reliably on older cards (e.g., Kepler series), newer Ampere and Ada GPUs require firmware extracts from proprietary blobs for viable operation, underscoring ongoing tensions between open-source ideals and vendor control over hardware specifics.[54]Intel Integrated Graphics Drivers

Intel's open-source graphics drivers for integrated GPUs (iGPUs) in its Core and Xeon processors form one of the most mature and fully upstreamed implementations in the Linux ecosystem, with kernel support via the i915 module in the Direct Rendering Manager (DRM) framework. The i915 driver manages hardware access, including display output, memory allocation, and GPU command execution, supporting Intel graphics hardware from the GMA 4500MHD (Gen4.5, introduced in 2008) onward, with extensions for earlier generations like the 915G chipset (2004). This driver integrates with the Linux kernel's graphics stack, enabling features such as kernel modesetting (KMS) since kernel version 2.6.28 (2008) and power management via runtime PM. Intel engineers contribute directly to upstream development, ensuring compatibility across generations without proprietary kernel modules.[40] In user space, Mesa provides the core API implementations, with the Iris driver—introduced experimentally in Mesa 19.0 (2019)—serving as the primary OpenGL and OpenGL ES renderer for Gen8 (Broadwell, 2014) and newer iGPUs using a Gallium3D backend for optimized state tracking and shader compilation. Iris achieves performance close to proprietary Windows drivers by utilizing hardware tessellation, geometry shaders, and texture compression, while the ANV driver handles Vulkan 1.3 conformance for the same hardware. For video acceleration, Intel's Media Driver implements VA-API for hardware decoding and encoding on Gen8+, supporting codecs like H.264, HEVC, and VP9. These components rely on the i915 or emerging Xe kernel driver for discrete-like functionality in newer integrated SoCs.[2] A key limitation persists in firmware requirements: Intel iGPUs depend on proprietary binary microcode for the Graphics Micro-Controller (GuC) and Video Processing Unit (HuC), distributed via the linux-firmware repository but without disclosed source code, necessitating non-free blobs for full functionality including power gating and media processing. Intel has open-sourced driver source code and specifications since the mid-2000s, commissioning early work from Tungsten Graphics, but firmware opacity stems from hardware design constraints rather than deliberate withholding. The experimental Xe driver, upstreamed in Linux 6.8 (2024), targets Gen12+ (Xe architecture, as in Tiger Lake 2020 and Meteor Lake 2023), promising modular improvements over i915 for future integrated graphics while maintaining backward compatibility. Overall, Intel's approach prioritizes upstream integration, yielding stable support superior to reverse-engineered alternatives for competitors.[55][56]Mobile and Embedded SoC Drivers

Open-source graphics drivers for mobile and embedded system-on-chip (SoC) GPUs have predominantly emerged through reverse-engineering efforts, as vendors such as Qualcomm, ARM, and Broadcom historically withhold detailed hardware documentation to protect intellectual property. These drivers target integrated GPUs in ARM-based SoCs used in smartphones, tablets, single-board computers, and IoT devices, where power efficiency and integration with Linux kernels like mainline or Android's are critical. Unlike discrete GPUs, SoC drivers must navigate tight resource constraints, including shared memory architectures and firmware dependencies, often resulting in partial feature parity with proprietary alternatives.[57][58] The Freedreno driver supports Qualcomm Adreno GPUs found in Snapdragon SoCs, such as those powering mobile devices and embedded systems. This community-driven effort, initially developed around 2012 through reverse engineering, achieved mainline kernel integration by 2017 and provides, within Mesa, the Freedreno implementation for OpenGL and OpenGL ES via Gallium3D, alongside the Turnip driver for Vulkan, enabling support in Linux-based projects like postmarketOS. As of September 2025, initial open-source kernel patches have begun supporting the Adreno 800 series in newer Snapdragon X Elite SoCs, though full user-space acceleration remains in early stages for recent generations. Performance lags proprietary drivers in high-end workloads due to incomplete firmware reverse-engineering, but it enables basic 3D acceleration on older Adreno models like A3xx to A6xx.[57] Panfrost serves as the primary open-source driver for ARM Mali GPUs based on Midgard, Bifrost, and Valhall architectures, common in mobile SoCs from manufacturers like Rockchip and Allwinner. This reverse-engineered, community-driven project gained ARM's official long-term support in 2023, with the Panthor kernel driver achieving OpenGL ES 3.1 conformance on the Mali-G610 by July 2024. This milestone enables compliant GLES rendering without binary blobs, supporting embedded Linux distributions on devices like the Raspberry Pi 5 alternatives and projects such as postmarketOS. Earlier Utgard Mali GPUs rely on the complementary Lima driver, which provides basic OpenGL ES 2.0 support but lacks advanced features. OpenCL C compute support landed in Mesa 25.1 in February 2025, expanding utility for AI and compute tasks in power-constrained environments.[59][60][61] Etnaviv targets Vivante GCxxx GPUs integrated into NXP i.MX SoCs for industrial embedded applications. This fully reverse-engineered driver, initiated in 2013, delivers OpenGL ES and Vulkan via Mesa's Gallium3D, with kernel improvements in Linux 6.11 enhancing performance for 2D/3D rendering as of June 2024. It supports PCI-attached variants since early 2024 patches, broadening compatibility beyond traditional SoC buses, though shader compilation and texture handling remain bottlenecks compared to vendor blobs.[62][63] For Broadcom VideoCore GPUs in Raspberry Pi embedded boards, the VC4 driver handles VideoCore IV hardware in models 1-3, supporting OpenGL ES 2.0 and OpenGL 2.1 through Mesa since its mainlining around 2014-2016. The newer V3D driver extends this to VideoCore VI in Pi 4 and later, enabling hardware-accelerated display outputs like HDMI and DSI. These drivers facilitate desktop environments and light gaming on resource-limited hardware, though they require firmware binaries for full initialization.[64][65] The Asahi Linux project provides a bespoke driver for Apple M-series SoCs, focusing on integrated GPUs in Mac hardware repurposed for Linux. Initial OpenGL 2.1/ES 2.0 support arrived in December 2022, with Vulkan and game compatibility advancing by October 2024, including Windows title acceleration via translation layers. Kernel driver refinements continued into Linux 6.17 as of October 2025, but development faced setbacks with key contributor Asahi Lina pausing work in March 2025 due to project dynamics. Despite progress, full feature parity with macOS drivers eludes it, particularly in power management for mobile-like thermal profiles.[66][67][68] Across these drivers, common limitations include incomplete Vulkan extensions, reliance on community funding over vendor incentives, and suboptimal power efficiency in battery-powered mobile scenarios, where proprietary stacks dominate Android ecosystems. Empirical benchmarks, such as those on Phoronix, show Panfrost achieving 70-90% of blob performance on Mali G52 in GLES workloads, underscoring viable but non-competitive viability for non-commercial embedded use.[60]Performance and Functional Analysis

Empirical Performance Benchmarks

Open-source graphics drivers exhibit performance characteristics that vary by hardware vendor and workload, with empirical tests demonstrating competitive results for AMD and Intel hardware in many scenarios, while NVIDIA's fully open-source alternatives lag behind proprietary options. In Vulkan and OpenGL benchmarks conducted by Phoronix in 2024, AMD's Mesa RADV driver on RDNA architectures often matched or exceeded the proprietary AMDGPU-PRO stack, particularly in gaming titles like Cyberpunk 2077 and DOOM Eternal, where Mesa achieved up to 10-15% higher frame rates due to community optimizations and integration with tools like Proton for Steam.[69][70] For compute workloads, such as Blender rendering, Mesa's ROCm integration on recent GPUs like the Radeon RX 7900 XTX delivered within 5% of proprietary performance, reflecting AMD's upstreaming of code to Mesa since 2016.[71] Intel's open-source i915 and Iris drivers, mature since the early 2010s, provide robust performance for integrated graphics in Haswell and later architectures, with Phoronix tests showing negligible differences—often under 2%—compared to Windows counterparts in 2D acceleration and light 3D tasks on Core i7 processors.[72] For discrete Arc GPUs, Linux benchmarks on the B580 in late 2024 revealed 85-95% of Windows 11 frame rates in titles like Shadow of the Tomb Raider at 1080p, with gaps attributed to ongoing Mesa ANV Vulkan driver maturation rather than kernel-level deficiencies; power draw remained comparable at 150-200W under load.[73] Recent Lunar Lake Xe2 evaluations in April 2025 indicated Linux achieving 96% of Windows performance in synthetic GPU tests like 3DMark, underscoring the efficacy of Intel's fully open-sourced stack for low-power mobile scenarios.[74] NVIDIA's Nouveau driver, a reverse-engineered open-source implementation, consistently underperforms the proprietary driver by 30-70% in 3DMark and Unigine benchmarks on Turing and earlier GPUs, with power efficiency suffering due to incomplete reclocking support—e.g., GTX 1080 tests in 2019 yielded 40 FPS versus 120 FPS in proprietary GLX gears.[53] Emerging NVK (Mesa Vulkan for NVIDIA) shows promise but trails by 20-50% in ray-tracing workloads on RTX 30-series cards as of 2024, limited by absent proprietary firmware blobs.[51] NVIDIA's partial open-sourcing of kernel modules in 2024 achieved exact parity with proprietary kernels in kernel-compile and compression tests on RTX 4090 hardware, but full user-space reliance on closed components prevents equivalent open-stack viability for high-end gaming or CUDA-accelerated tasks.[75][6]| Vendor | Driver Stack | Key Benchmark Example | Performance Relative to Proprietary/Windows | Date/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD | Mesa (RADV/RadeonSI) | Vulkan gaming (RX 7900 XTX) | 100-115% in select titles | 2023-2024/Phoronix, community tests[69] |

| Intel | Iris/ANV | 3DMark (Arc B580) | 85-96% of Windows | 2024-2025/Phoronix[73] |

| NVIDIA | Nouveau/NVK | OpenGL/Unigine (RTX 30-series) | 30-70% deficit | 2019-2024/Phoronix[53] |

Feature Support and Compatibility Gaps

Open-source graphics device drivers, while providing essential rendering and display capabilities, frequently exhibit gaps in supporting advanced hardware features compared to proprietary counterparts, particularly in dynamic clocking, power management, and full API conformance across hardware generations. For NVIDIA hardware, the Nouveau driver struggles with reclocking and efficient power states on Turing and later architectures, limiting performance in compute-intensive workloads and leading to thermal throttling under load.[76] These limitations stem from reverse-engineering challenges, resulting in incomplete support for features like GPU boost clocks, which proprietary drivers enable for up to 50-100% higher frame rates in benchmarks.[77] Vulkan support via the NVK driver achieves 1.4 conformance on recent Blackwell GPUs but remains at 1.2 for older Kepler series due to inherent hardware constraints, excluding some modern extensions like dynamic rendering.[78] Efforts to close these gaps, including 2025 commitments for enhanced NVIDIA compatibility in Mesa, have improved basic Vulkan functionality but not yet matched proprietary driver maturity.[79] AMD's amdgpu driver offers stronger feature parity for RDNA and recent GCN GPUs, supporting OpenGL 4.6 and Vulkan 1.3+ with near-complete hardware acceleration, though legacy Southern Islands (GCN 1.0) cards lacked Video Coding Engine 1.0 decode until upstream patches merged in October 2025.[80] Compatibility gaps persist in older firmware-dependent features, such as certain AV1 encoding modes, requiring proprietary blobs for full utilization, which introduces dependency on non-open components.[38] These issues affect video transcoding efficiency, with open-source paths yielding 20-30% lower throughput on affected hardware relative to closed-source alternatives.[80] Intel's i915 and Xe drivers for integrated and discrete graphics demonstrate fewer systemic gaps, with robust OpenGL 4.6 and Vulkan 1.3 support across generations from Sandy Bridge to Arc Alchemist, enabled by vendor-provided documentation.[36] However, compatibility issues arise in niche scenarios, such as incomplete extension support for variable rate shading on pre-Xe hardware, and occasional crashes in applications like Adobe Premiere due to driver version mismatches rather than core feature absences.[81] Mesa's overall implementation addresses many historical gaps, including Vulkan 1.4 on legacy GPUs in the 25.1 release, but select drivers fall short of full OpenGL 4.6 requirements, impacting shader model compliance in professional workflows.[36] These disparities highlight how open-source progress relies on community and partial vendor contributions, often trailing by 1-2 years for cutting-edge features.Power Efficiency and Stability Metrics