Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Habenula

View on Wikipedia| Habenula | |

|---|---|

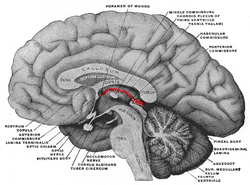

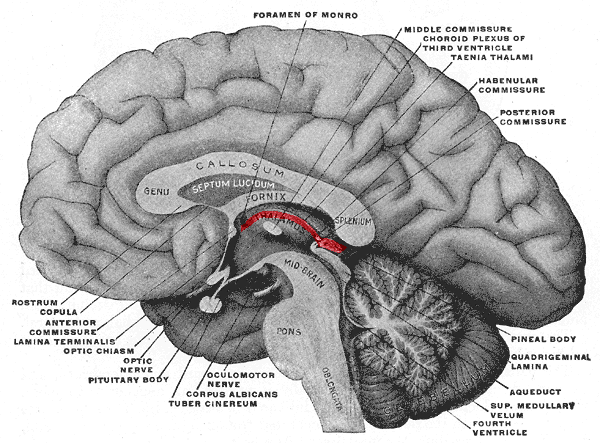

Medial aspect of human brain showing location of the habenula in front of the pineal gland or body in the epithalamus shown in red The habenular commissure is labelled shown connecting the habenula. | |

Habenula shown in blue just in front of the pineal gland shown in red | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D019262 |

| NeuroNames | 294 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1611 |

| TA98 | A14.1.08.003 |

| TA2 | 5662 |

| FMA | 62032 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The habenula (diminutive of Latin habena, meaning "rein") is a small bilateral neuronal structure in the brain of vertebrates, that has also been called a microstructure since it is no bigger than a pea. The naming as "little rein" describes its elongated shape in the epithalamus, where it borders the third ventricle, and lies in front of the pineal gland.[1]

Although it is a microstructure each habenular nucleus is divided into two distinct regions of nuclei, a medial habenula (MHb), and a lateral habenula (LHb) both having different neuronal populations, inputs, and outputs.[2][3] The medial habenula can be subdivided into five subnuclei, the lateral habenula into four subnuclei.[4] Research has shown morphological complexity in the MHb and LHb. Different inputs to the MHb are discriminated between the different subnuclei.[5] In the two regions of nuclei there is a difference in gene expression giving different functions to each.[6]

The habenula is a conserved structure across vertebrates. In mammals it is highly symmetric, and in fish, amphibians and reptiles it is highly asymmetric in size, molecular composition, and connections.[1] The habenular nuclei are a major component in the limbic system pathways.[1] The fasciculus retroflexus pathway between the habenula and the interpeduncular nucleus is one of the first major nerve tracts to form in the developing brain.[1]

The habenula is a central structure that connects forebrain regions to midbrain regions, and acts as a hub or node for the integration of emotional and sensory processing.[2] It integrates information from the limbic system, sensory and basal ganglia to guide appropriate and effective responses.[5] The habenula is involved in the regulation of monoamine neurotransmitters notably dopamine and serotonin.[2][3] Both of these neurotransmitters are strongly associated with anxiety disorders, and avoidance behaviours.[2] The functions of the habenula are also involved in motivation, emotion, learning, and pain.[2] The MHb plays an important role in depression, stress, memory, and nicotine withdrawal, as well as a role in cocaine, methamphetamine and alcohol addiction.[6] The MHb shows a high level of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), that are involved in many forms of addiction. Previously their expression was only noted in other structures associated with addiction. Their expression in the MHb has become a later focus of research.[6]

Anatomy

[edit]Each habenular nucleus has two divisions, a medial habenular nucleus (MHb), and a lateral habenular nucleus (LHb). Studies have shown that the medial habenula can be subdivided into five subnuclei, and the lateral habenula into four subnuclei.[4] The right and left habenular nuclei are connected to each other by the habenular commissure. The pineal gland is attached to the brain in this region.[7] The medial habenula (MHb) receives connections from posterior septum pellucidum and diagonal band of Broca; the lateral habenula receives afferents from the lateral hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, internal globus pallidus, ventral pallidum, and diagonal band of Broca.[8] As a whole, this complexly interconnected region is part of the dorsal diencephalic conduction system (DDCS), responsible for relaying information from the limbic system to the midbrain, hindbrain, and medial forebrain.[9][10]

Lateral habenula

[edit]The primary input regions to the lateral habenula (LHb) are the lateral preoptic area (bringing input from the hippocampus and lateral septum), the ventral pallidum (bringing input from the nucleus accumbens and mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus), the lateral hypothalamus, the medial habenula, and the internal segment of the globus pallidus (bringing input from other basal ganglia structures).[8]

Neurons in the lateral habenula are 'reward-negative' as they are activated by stimuli associated with unpleasant events, the absence of the reward or the presence of punishment especially when this is unpredictable.[11] Reward information to the lateral habenula comes from the internal part of the globus pallidus.[12]

The outputs of the lateral habenula target dopaminergic regions (substantia nigra pars compacta and the ventral tegmental area), serotonergic regions (median raphe and dorsal raphe nuclei), and a cholinergic region (the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus).[8] This output inhibits dopamine neurons in substantia nigra pars compacta and the ventral tegmental area, with activation in the lateral habenula linking to deactivation in them, and vice versa, deactivation in the lateral habenula with their activation.[13] The lateral habenula functions to oppose the action of the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus in the acquisition of avoidance responses but not the processing of avoidance later on when it is a memory, motivation or its execution.[14] Research suggests that lateral habenula may play a crucial role in decision making.[15]

There has also shown to be an association with aberrant LHb activity and depression.[16]

Medial habenula

[edit]The medial habenula (MHb) receives connections from the posterior septum pellucidum and diagonal band of Broca.[8] Input to the medial habenula comes from a variety of regions and carries a number of different chemicals. Most neuronal projections to the MHb come from the septal area.[5] Input regions include septal nuclei (the nucleus fimbrialis septi and the nucleus triangularis septi); dopaminergic inputs from the interfascicular nucleus of the ventral tegmental area, noradrenergic inputs from the locus ceruleus, and GABAergic inputs from the diagonal band of Broca. The medial habenula sends outputs of glutamate, substance P and acetylcholine to the periaqueductal gray via the interpeduncular nucleus as well as to the pineal gland.[17][18]

Asymmetry

[edit]Asymmetry in the habenula was first noted in 1883 by Nikolaus Goronowitsch.[7] Various species exhibit left-right asymmetric differentiation of habenular neurons. In many fishes and amphibians, the habenula on one side is significantly larger and better organized into distinct nuclei in the dorsal diencephalon than its smaller pair. The sidedness of such differentiation (whether the left or the right is more developed) varies with the species. In birds and mammals, however, both habenulae are more symmetrical (although not entirely) and consist of a medial and a lateral nucleus on each side which is in fish and amphibians equivalent to dorsal habenula and the ventral habenula, respectively.[19][8][20]

Olfactory coding

[edit]In some fish (lampreys and teleosts), mitral cell (principal olfactory neurons) axons project exclusively to the right hemisphere of the habenula in an asymmetric manner. It is reported that the dorsal habenula (DHb) are functionally asymmetric with predominantly odor responses in the right hemisphere. It was also shown that DHb neurons are spontaneously active even in the absence of olfactory stimulation. These spontaneously-active DHb neurons are organized into functional clusters which were proposed to govern olfactory responses.[21]

Functions

[edit]These nuclei are hypothesized to be involved in regulation of monoamines, such as dopamine and serotonin.[22][23]

The habenular nuclei are involved in fear memory,[24][25] pain processing,[26] reproductive behavior, nutrition, sleep-wake cycles, stress responses, and learning. Recent demonstrations using fMRI[27] and single unit electrophysiology[13] have closely linked the function of the lateral habenula with reward processing, in particular with regard to encoding negative feedback or negative rewards. Matsumoto and Hikosaka suggested in 2007 that this reward and reward-negative information in the brain might "be elaborated through the interplay among the lateral habenula, the basal ganglia, and monoaminergic (dopaminergic and serotonergic) systems" and that the lateral habenula may play a pivotal role in this "integrative function".[13] Then, Bromberg-Martin et al. (2011) highlighted that neurons in the lateral habenula signal positive and negative information-prediction errors in addition to positive and negative reward-prediction errors.[28]

Depression

[edit]Both the medial and lateral habenula show reduced volume in those with depression. Neuron cell numbers were also reduced on the right side.[29] Such changes are not seen in those with schizophrenia.[29] Deep brain stimulation of the major afferent bundle (i.e., stria medullaris thalami) of the lateral habenula has been used for treatment of depression where it is severe, protracted and therapy-resistant.[30][31]

N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent burst firing in the lateral habenula has been associated with depression in animal studies,[32] and it has been shown that the general anesthetic ketamine blocks this firing by acting as a receptor antagonist.[33] Ketamine has been the subject of numerous studies after having shown fast-acting antidepressant effects in humans (in a 0.5 mg/bw kg dose).[34]

Motivation and addiction

[edit]Recent exploration of the habenular nuclei has begun to associate the structure with an organism's current mood, feeling of motivation, and reward recognition.[35] Previously, the LHb has been identified as an "anti-reward" signal, but recent research suggests that the LHb helps identify preference, helping the brain to discriminate between potential actions and subsequent motivation decisions.[36] In a study using a Pavlovian conditioning model, results showed an increase in the habenula response.[37] This increase coincided with conditioned stimuli associated with more aversive punishments (i.e. electric shock).[37] Therefore, researchers speculate that inhibition or damage to the LHb resulting in a failure to process such information may lead to random motivation behavior.[36][37]

LHb is especially important in understanding the reward and motivation relationship as it relates to addictive behaviors.[35] The LHb inhibits dopaminergic neurons, decreasing the release of dopamine.[38] It was determined by several animal studies that receiving a reward coincided with elevated dopamine levels, but once the learned association was learned by the animal, dopamine levels remain elevated, only decreasing when the reward is removed.[20][23][35][38] Therefore, dopamine levels only increase with unpredicted rewards and with a "positive prediction error".[20] Moreover, it was determined that removal of an anticipated award activated LHb, inhibited dopamine levels.[20] This finding helps explain why addictive drugs are associated with elevated dopamine levels.[20]

Nicotine and nAChRs

[edit]Despite common misconceptions regarding the relaxing effects of tobacco and nicotine use, behavioral testing in animals has demonstrated nicotine to have an anxiogenic effect.[39] Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) have been identified as the primary site for nicotine activity and regulate consequent cellular polarization.[40] nAChRs are made up a number of α and β subunits and are found in both the LHb and MHb, where research suggests they may play a key role in addiction and withdrawal behaviors.[40][41]

History

[edit]The habenular is a well conserved structure that appeared in vertebrates more than 360 million years ago.[4] The habenular commissure was described for the first time in 1555 by Andreas Vesalius[42] and the habenula nuclei in 1872 by Theodor Hermann Meynert.[43]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Antolin-Fontes, B; Ables, JL; Görlich, A; Ibañez-Tallon, I (September 2015). "The habenulo-interpeduncular pathway in nicotine aversion and withdrawal". Neuropharmacology. 96 (Pt B): 213–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.11.019. PMC 4452453. PMID 25476971.

- ^ a b c d e Antunes, GF; Campos, ACP; Martins, DO; Gouveia, FV; Rangel Junior, MJ; Pagano, RL; Martinez, RCR (27 June 2023). "Unravelling the Role of Habenula Subnuclei on Avoidance Response: Focus on Activation and Neuroinflammation". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (13) 10693. doi:10.3390/ijms241310693. PMC 10342060. PMID 37445871.

- ^ a b Boulos, LJ; Darcq, E; Kieffer, BL (15 February 2017). "Translating the Habenula-From Rodents to Humans". Biological Psychiatry. 81 (4): 296–305. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.06.003. PMC 5143215. PMID 27527822.

- ^ a b c Ables, JL; Park, K; Ibañez-Tallon, I (April 2023). "Understanding the habenula: A major node in circuits regulating emotion and motivation". Pharmacological Research. 190 106734. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2023.106734. PMC 11081310. PMID 36933754.

- ^ a b c Juárez-Leal, I; Carretero-Rodríguez, E; Almagro-García, F; Martínez, S; Echevarría, D; Puelles, E (16 June 2022). "Stria medullaris innervation follows the transcriptomic division of the habenula". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 10118. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1210118J. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-14328-1. PMC 9203815. PMID 35710872.

- ^ a b c Viswanath, H; Carter, AQ; Baldwin, PR; Molfese, DL; Salas, R (2013). "The medial habenula: still neglected". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 7: 931. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00931. PMC 3894476. PMID 24478666.

- ^ a b Guglielmotti, Vittorio; Cristino, Luigia (2006). "The interplay between the pineal complex and the habenular nuclei in lower vertebrates in the context of the evolution of cerebral asymmetry". Brain Research Bulletin. 69 (5): 475–488. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.03.010. ISSN 0361-9230. PMID 16647576. S2CID 24786037.

- ^ a b c d e Geisler S, Trimble M (June 2008). "The lateral habenula: no longer neglected". CNS Spectrums. 13 (6): 484–9. doi:10.1017/S1092852900016710. PMID 18567972. S2CID 37331212.

- ^ Beretta, Carlo Antonio; Dross, Nicolas; Gutierrez-Triana, Jose Arturo; Ryu, Soojin; Carl, Matthias (2012-01-01). "Habenula circuit development: past, present, and future". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 6: 51. doi:10.3389/fnins.2012.00051. PMC 3332237. PMID 22536170.

- ^ Bianco, Isaac H.; Wilson, Stephen W. (2009-04-12). "The habenular nuclei: a conserved asymmetric relay station in the vertebrate brain". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1519): 1005–1020. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0213. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2666075. PMID 19064356.

- ^ Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O (January 2009). "Representation of negative motivational value in the primate lateral habenula". Nature Neuroscience. 12 (1): 77–84. doi:10.1038/nn.2233. PMC 2737828. PMID 19043410.

- ^ Hong S, Hikosaka O (November 2008). "The globus pallidus sends reward-related signals to the lateral habenula". Neuron. 60 (4): 720–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.035. PMC 2638585. PMID 19038227.

- ^ a b c Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O (June 2007). "Lateral habenula as a source of negative reward signals in dopamine neurons". Nature. 447 (7148): 1111–5. Bibcode:2007Natur.447.1111M. doi:10.1038/nature05860. PMID 17522629. S2CID 4418279.

- ^ Shumake J, Ilango A, Scheich H, Wetzel W, Ohl FW (April 2010). "Differential neuromodulation of acquisition and retrieval of avoidance learning by the lateral habenula and ventral tegmental area". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (17): 5876–83. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3604-09.2010. PMC 6632612. PMID 20427648.

- ^ Stopper CM, Floresco SB (January 2014). "What's better for me? Fundamental role for lateral habenula in promoting subjective decision biases". Nature Neuroscience. 17 (1): 33–5. doi:10.1038/nn.3587. PMC 4974073. PMID 24270185.

- "Scientists find brain region that helps you make up your mind". ScienceDaily (Press release). November 24, 2013.

- ^ Yang Y, Wang H, Hu J, Hu H (February 2018). "Lateral habenula in the pathophysiology of depression". Curr Opin Neurobiol. 48: 90–96. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2017.10.024. PMID 29175713.

- ^ Lecourtier L, Kelly PH (January 2007). "A conductor hidden in the orchestra? Role of the habenular complex in monoamine transmission and cognition". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 31 (5): 658–72. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.01.004. PMID 17379307. S2CID 12856377.

- ^ Antolin-Fontes B, Ables JL, Görlich A, Ibañez-Tallon I (September 2015). "The habenulo-interpeduncular pathway in nicotine aversion and withdrawal". Neuropharmacology. 96 (Pt B): 213–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.11.019. PMC 4452453. PMID 25476971.

- ^ Hüsken U, Stickney HL, Gestri G, Bianco IH, Faro A, Young RM, Roussigne M, Hawkins TA, Beretta CA, Brinkmann I, Paolini A, Jacinto R, Albadri S, Dreosti E, Tsalavouta M, Schwarz Q, Cavodeassi F, Barth AK, Wen L, Zhang B, Blader P, Yaksi E, Poggi L, Zigman M, Lin S, Wilson SW, Carl M (October 2014). "Tcf7l2 is required for left-right asymmetric differentiation of habenular neurons". Current Biology. 24 (19): 2217–27. Bibcode:2014CBio...24.2217H. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.006. PMC 4194317. PMID 25201686.

- ^ a b c d e Hu, Hailan; Cui, Yihui; Yang, Yan (April 2020). "Circuits and functions of the lateral habenula in health and in disease". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 21 (5): 277–295. doi:10.1038/s41583-020-0292-4. ISSN 1471-0048. PMID 32269316. S2CID 215411587.

- ^ Jetti SK, Vendrell-Llopis N, Yaksi E (February 2014). "Spontaneous activity governs olfactory representations in spatially organized habenular microcircuits". Current Biology. 24 (4): 434–9. Bibcode:2014CBio...24..434J. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.015. PMID 24508164.

- ^ Stephenson-Jones, Marcus; Floros, Orestis; Robertson, Brita; Grillner, Sten (2011). "Evolutionary conservation of the habenular nuclei and their circuitry controlling the dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HT) systems". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (3): E164 – E173. doi:10.1073/pnas.1119348109. PMC 3271889. PMID 22203996.

- ^ a b Boulos, Laura-Joy; Darcq, Emmanuel; Kieffer, Brigitte Lina (2017-02-15). "Translating the Habenula—From Rodents to Humans". Biological Psychiatry. 81 (4): 296–305. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.06.003. PMC 5143215. PMID 27527822.

- ^ Zhang, Juen; Tan, Lubin; Ren, Yuqi; Liang, Jingwen; Lin, Rui; Feng, Qiru; Zhou, Jingfeng; Hu, Fei; Ren, Jing; Wei, Chao; Yu, Tao; Zhuang, Yinghua; Bettler, Bernhard; Wang, Fengchao; Luo, Minmin (July 2016). "Presynaptic Excitation via GABA B Receptors in Habenula Cholinergic Neurons Regulates Fear Memory Expression". Cell. 166 (3): 716–728. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.026.

- ^ Soria-Gómez, Edgar; Busquets-Garcia, Arnau; Hu, Fei; Mehidi, Amine; Cannich, Astrid; Roux, Liza; Louit, Ines; Alonso, Lucille; Wiesner, Theresa; Georges, Francois; Verrier, Danièle; Vincent, Peggy; Ferreira, Guillaume; Luo, Minmin; Marsicano, Giovanni (October 2015). "Habenular CB1 Receptors Control the Expression of Aversive Memories". Neuron. 88 (2): 306–313. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.035.

- ^ Hu, Fei; Ren, Jing; Zhang, Ju-en; Zhong, Weixin; Luo, Minmin (2012-10-23). "Natriuretic peptides block synaptic transmission by activating phosphodiesterase 2A and reducing presynaptic PKA activity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (43): 17681–17686. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209185109. PMC 3491473. PMID 23045693.

- ^ Ullsperger M, von Cramon DY (May 2003). "Error monitoring using external feedback: specific roles of the habenular complex, the reward system, and the cingulate motor area revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging". The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (10): 4308–14. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04308.2003. PMC 6741115. PMID 12764119.

- ^ Bromberg-Martin ES, Hikosaka O (August 2011). "Lateral habenula neurons signal errors in the prediction of reward information". Nature Neuroscience. 14 (9): 1209–16. doi:10.1038/nn.2902. PMC 3164948. PMID 21857659.

- ^ a b Ranft K, Dobrowolny H, Krell D, Bielau H, Bogerts B, Bernstein HG (April 2010). "Evidence for structural abnormalities of the human habenular complex in affective disorders but not in schizophrenia". Psychological Medicine. 40 (4): 557–67. doi:10.1017/S0033291709990821. PMID 19671211. S2CID 11799795.

- ^ Sartorius A, Kiening KL, Kirsch P, von Gall CC, Haberkorn U, Unterberg AW, Henn FA, Meyer-Lindenberg A (January 2010). "Remission of major depression under deep brain stimulation of the lateral habenula in a therapy-refractory patient". Biological Psychiatry. 67 (2): e9 – e11. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.027. PMID 19846068. S2CID 43590983.

- ^ Juckel G, Uhl I, Padberg F, Brüne M, Winter C (February 2009). "Psychosurgery and deep brain stimulation as ultima ratio treatment for refractory depression". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 259 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s00406-008-0826-7. PMID 19137233. S2CID 27076192.

- ^ Howe WM, Kenny PJ (February 2018). "Burst firing sets the stage for depression". Nature. 554 (7692): 304–305. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..304H. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-01588-z. PMID 29446408.

- ^ Yang Y, Cui Y, Sang K, Dong Y, Ni Z, Ma S, Hu H (February 2018). "Ketamine blocks bursting in the lateral habenula to rapidly relieve depression". Nature. 554 (7692): 317–322. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..317Y. doi:10.1038/nature25509. PMID 29446381. S2CID 3334820.

- ^ Serafini G, Howland RH, Rovedi F, Girardi P, Amore M (September 2014). "The role of ketamine in treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review". Current Neuropharmacology. 12 (5): 444–61. doi:10.2174/1570159X12666140619204251. PMC 4243034. PMID 25426012.

- ^ a b c Fakhoury, Marc; López, Domínguez. "The Role of Habenula in Motivation and Reward". Advances in Neuroscience.

- ^ a b Stopper, Colin M; Floresco, Stan B (24 November 2013). "What's better for me? Fundamental role for lateral habenula in promoting subjective decision biases". Nature Neuroscience. 17 (1): 33–35. doi:10.1038/nn.3587. PMC 4974073. PMID 24270185.

- ^ a b c Lawson, Rebecca P.; Seymour, Ben; Loh, Eleanor; Lutti, Antoine; Dolan, Raymond J.; Dayan, Peter; Weiskopf, Nikolaus; Roiser, Jonathan P. (2014-08-12). "The habenula encodes negative motivational value associated with primary punishment in humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (32): 11858–11863. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11111858L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1323586111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4136587. PMID 25071182.

- ^ a b Hikosaka, Okihide; Sesack, Susan R.; Lecourtier, Lucas; Shepard, Paul D. (2008-11-12). "Habenula: Crossroad between the Basal Ganglia and the Limbic System". Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (46): 11825–11829. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3463-08.2008. PMC 2613689. PMID 19005047.

- ^ Casarrubea, Maurizio; Davies, Caitlin; Faulisi, Fabiana; Pierucci, Massimo; Colangeli, Roberto; Partridge, Lucy; Chambers, Stephanie; Cassar, Daniel; Valentino, Mario (2015-01-01). "Acute nicotine induces anxiety and disrupts temporal pattern organization of rat exploratory behavior in hole-board: a potential role for the lateral habenula". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 9: 197. doi:10.3389/fncel.2015.00197. PMC 4450172. PMID 26082682.

- ^ a b Zuo, Wanhong; Xiao, Cheng; Gao, Ming; Hopf, F. Woodward; Krnjević, Krešimir; McIntosh, J. Michael; Fu, Rao; Wu, Jie; Bekker, Alex (2016-09-06). "Nicotine regulates activity of lateral habenula neurons via presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms". Scientific Reports. 6 32937. Bibcode:2016NatSR...632937Z. doi:10.1038/srep32937. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5011770. PMID 27596561.

- ^ Dao, Dang Q.; Perez, Erika E.; Teng, Yanfen; Dani, John A.; De Biasi, Mariella (2014-03-19). "Nicotine Enhances Excitability of Medial Habenular Neurons via Facilitation of Neurokinin Signaling". Journal of Neuroscience. 34 (12): 4273–4284. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2736-13.2014. PMC 3960468. PMID 24647947.

- ^ Turliuc, Dana; Turliuc, Șerban; Cucu, Andrei; Dumitrescu, Gabriela; Costea, Claudia (2015-11-19). "An entire universe of the Roman world's architecture found in the human skull". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 26 (1): 88–100. doi:10.1080/0964704x.2015.1099382. ISSN 0964-704X. PMID 26584250. S2CID 21254791.

- ^ Turliuc, Dana; Turliuc, Şerban; Cucu, Andrei; Dumitrescu, Gabriela Florenţa; Cărăuleanu, Alexandru; Buzdugă, Cătălin; Tamaş, Camelia; Sava, Anca; Costea, Claudia Florida (2016). "A review of analogies between some neuroanatomical terms and roman household objects". Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 204: 127–133. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2015.07.001. ISSN 0940-9602. PMID 26337365.