Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Haber process

View on WikipediaThis article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (November 2023) |

The Haber process,[1] also called the Haber–Bosch process, is the main industrial procedure for the production of ammonia.[2][3] It converts atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) by a reaction with hydrogen (H2) using finely divided iron metal as a catalyst:

This reaction is exothermic but disfavored in terms of entropy because four equivalents of reactant gases are converted into two equivalents of product gas. As a result, sufficiently high pressures and temperatures are needed to drive the reaction forward.

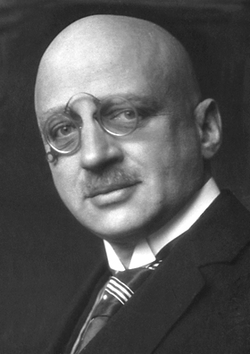

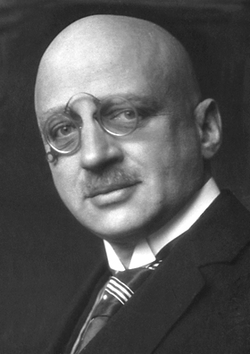

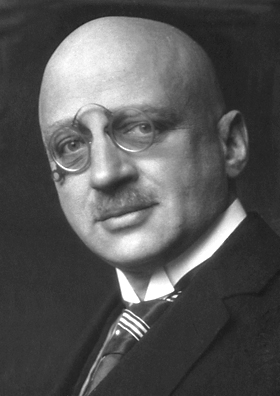

The German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed the process in the first decade of the 20th century, and its improved efficiency over existing methods such as the Birkeland-Eyde and Frank-Caro processes was a major advancement in the industrial production of ammonia.[4][5][6]

The Haber process can be combined with steam reforming to produce ammonia with just three chemical inputs: water, natural gas, and atmospheric nitrogen. Both Haber and Bosch were eventually awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry: Haber in 1918 for ammonia synthesis specifically, and Bosch in 1931 for related contributions to high-pressure chemistry.

History

[edit]

During the 19th century, the demand rapidly increased for nitrates and ammonia for use as fertilizers, which supply plants with the nutrients they need to grow, and for industrial feedstocks. The main source was mining niter deposits and guano from tropical islands.[7] At the beginning of the 20th century these reserves were thought insufficient to satisfy future demands,[8] and research into new potential sources of ammonia increased. Although atmospheric nitrogen (N2) is abundant, comprising ~78% of the air, it is exceptionally stable and does not readily react with other chemicals.

Haber, with his assistant Robert Le Rossignol,[9][10] developed the high-pressure devices and catalysts needed to demonstrate the Haber process at a laboratory scale.[11][12] They demonstrated their process in the summer of 1909 by producing ammonia from the air, drop by drop, at the rate of about 125 mL (4 US fl oz) per hour. The process was purchased by the German chemical company BASF, which assigned Carl Bosch the task of scaling up Haber's tabletop machine to industrial scale.[5][13] He succeeded in 1910. Haber and Bosch were later awarded Nobel Prizes, in 1918 and 1931 respectively, for their work in overcoming the chemical and engineering problems of large-scale, continuous-flow, high-pressure technology.[5]

Ammonia was first manufactured using the Haber process on an industrial scale in 1913 in BASF's Oppau plant in Germany, reaching 20 tonnes/day in 1914.[14] During World War I, the production of munitions required large amounts of nitrate. The Allied powers had access to large deposits of sodium nitrate in Chile (Chile saltpetre) controlled by British companies. India had large supplies too, but it was also controlled by the British.[15] Moreover, even if German commercial interests had nominal legal control of such resources, the Allies controlled the sea lanes and imposed a highly effective blockade which would have prevented such supplies from reaching Germany. The Haber process proved so essential to the German war effort[5][16] that it is considered virtually certain Germany would have been defeated in a matter of months without it. Synthetic ammonia from the Haber process was used for the production of nitric acid, a precursor to the nitrates used in explosives.

The original Haber–Bosch reaction chambers used osmium as the catalyst, but this was available in extremely small quantities. Haber noted that uranium was almost as effective and easier to obtain than osmium. In 1909, BASF researcher Alwin Mittasch discovered a much less expensive iron-based catalyst that is still used. A major contributor to the discovery of this catalysis was Gerhard Ertl.[17][18][19][20] The most popular catalysts are based on iron promoted with K2O, CaO, SiO2, and Al2O3.

During the interwar years, alternative processes were developed, most notably the Casale process, the Claude process, and the Mont-Cenis process developed by the Friedrich Uhde Ingenieurbüro.[21] [better source needed] Luigi Casale and Georges Claude proposed to increase the pressure of the synthesis loop to 80–100 MPa (800–1,000 bar; 12,000–15,000 psi), thereby increasing the single-pass ammonia conversion and making nearly complete liquefaction at ambient temperature feasible. Claude proposed to have three or four converters with liquefaction steps in series, thereby avoiding recycling. Most plants continue to use the original Haber process (20 MPa (200 bar; 2,900 psi) and 500 °C (932 °F)), albeit with improved single-pass conversion and lower energy consumption due to process and catalyst optimization.

Process

[edit]

Combined with the energy needed to produce hydrogen and purified atmospheric nitrogen, ammonia production is energy-intensive, accounting for 1% to 2% of global energy consumption, 3% of global carbon emissions,[22] and 3% to 5% of natural gas consumption.[23] Hydrogen required for ammonia synthesis is most often produced through gasification of hydrocarbons, mostly natural gas, but other potential hydrogen sources include coal, petroleum, peat, biomass, or waste. As of 2012, the global production of ammonia produced from natural gas using the steam reforming process was 72%,[24] however in China as of 2022 natural gas and coal were responsible for 20% and 75% respectively.[25] Hydrogen can also be produced from water and electricity using electrolysis: at one time, most of Europe's ammonia was produced from the Hydro plant at Vemork. Other possibilities include biological hydrogen production or photolysis, but at present, steam reforming of natural gas is the most economical means of mass-producing hydrogen.

The choice of catalyst is important for synthesizing ammonia. In 2012, Hideo Hosono's group found that Ru-loaded calcium-aluminium oxide C12A7:e− electride works well as a catalyst and pursued more efficient formation.[26][27] This method is implemented in a small plant for ammonia synthesis in Japan.[28][29] In 2019, Hosono's group found another catalyst, a novel perovskite oxynitride-hydride BaCeO3−xNyHz, that works at lower temperature and without costly ruthenium.[30]

Hydrogen production

[edit]The major source of hydrogen is methane. Steam reforming of natural gas extracts hydrogen from methane in a high-temperature and pressure tube inside a reformer with a nickel catalyst. Other fossil fuel sources include coal, heavy fuel oil and naphtha.

Green hydrogen is produced without fossil fuels or carbon dioxide emissions from biomass, water electrolysis and thermochemical (solar or another heat source) water splitting.[31][32][33]

Starting with a natural gas (CH

4) feedstock, the steps are as follows;

- Remove sulfur compounds from the feedstock, because sulfur deactivates the catalysts used in subsequent steps. Sulfur removal requires catalytic hydrogenation to convert sulfur compounds in the feedstocks to gaseous hydrogen sulfide (hydrodesulfurization, hydrotreating):

- Hydrogen sulfide is adsorbed and removed by passing it through beds of zinc oxide where it is converted to solid zinc sulfide:

- Catalytic steam reforming of the sulfur-free feedstock forms hydrogen plus carbon monoxide:

- Catalytic shift conversion converts the carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide and more hydrogen:

- Carbon dioxide is removed either by absorption in aqueous ethanolamine solutions or by adsorption in pressure swing adsorbers (PSA) using proprietary solid adsorption media.

- The final step in producing hydrogen is to use catalytic methanation to remove residual carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide:

Ammonia production

[edit]The hydrogen is catalytically reacted with nitrogen (derived from air separation[clarification needed]) to form anhydrous liquid ammonia. It is difficult and expensive, as lower temperatures result in slower reaction kinetics (hence a slower reaction rate)[34] and high pressure requires high-strength pressure vessels[35] that resist hydrogen embrittlement. Diatomic nitrogen is bound together by a triple bond, which makes it relatively inert.[36][37] Yield and efficiency are low, meaning that the ammonia must be extracted and the gases reprocessed for the reaction to proceed at an acceptable pace.[38]

This step is known as the ammonia synthesis loop:

The gases (nitrogen and hydrogen) are passed over four beds of catalyst, with cooling between each pass to maintain a reasonable equilibrium constant. On each pass, only about 15% conversion occurs, but unreacted gases are recycled, and eventually conversion of 97% is achieved.[3]

Due to the nature of the (typically multi-promoted magnetite) catalyst used in the ammonia synthesis reaction, only low levels of oxygen-containing (especially CO, CO2 and H2O) compounds can be tolerated in the hydrogen/nitrogen mixture. Relatively pure nitrogen can be obtained by air separation, but additional oxygen removal may be required.

Because of relatively low single pass conversion rates (typically less than 20%), a large recycle stream is required. This can lead to the accumulation of inerts in the gas.

Nitrogen gas (N2) is unreactive because the atoms are held together by triple bonds. The Haber process relies on catalysts that accelerate the scission of these bonds.

Two opposing considerations are relevant: the equilibrium position and the reaction rate. At room temperature, the equilibrium is in favor of ammonia, but the reaction does not proceed at a detectable rate due to its high activation energy. Because the reaction is exothermic, the equilibrium constant decreases with increasing temperature following Le Châtelier's principle. It becomes unity at around 150–200 °C (302–392 °F).[3]

| Temperature (°C) |

Kp [clarification needed] |

|---|---|

| 300 | 4.34 × 10−3 |

| 400 | 1.64 × 10−4 |

| 450 | 4.51 × 10−5 |

| 500 | 1.45 × 10−5 |

| 550 | 5.38 × 10−6 |

| 600 | 2.25 × 10−6 |

Above this temperature, the equilibrium quickly becomes unfavorable at atmospheric pressure, according to the Van 't Hoff equation. Lowering the temperature is unhelpful because the catalyst requires a temperature of at least 400 °C to be efficient.[3]

Increased pressure favors the forward reaction because 4 moles of reactant produce 2 moles of product, and the pressure used (15–25 MPa (150–250 bar; 2,200–3,600 psi)) alters the equilibrium concentrations to give a substantial ammonia yield. The reason for this is evident in the equilibrium relationship:

where is the fugacity coefficient of species , is the mole fraction of the same species, is the reactor pressure, and is standard pressure, typically 1 bar (0.10 MPa).

Economically, reactor pressurization is expensive: pipes, valves, and reaction vessels need to be strong enough, and safety considerations affect operating at 20 MPa. Compressors take considerable energy, as work must be done on the (compressible) gas. Thus, the compromise used gives a single-pass yield of around 15%.[3]

While removing the ammonia from the system increases the reaction yield, this step is not used in practice, since the temperature is too high; instead it is removed from the gases leaving the reaction vessel. The hot gases are cooled under high pressure, allowing the ammonia to condense and be removed as a liquid. Unreacted hydrogen and nitrogen gases are returned to the reaction vessel for another round.[3] While most ammonia is removed (typically down to 2–5 mol.%), some ammonia remains in the recycle stream. In academic literature, a more complete separation of ammonia has been proposed by absorption in metal halides, metal-organic frameworks or zeolites.[40] Such a process is called an absorbent-enhanced Haber process or adsorbent-enhanced Haber–Bosch process.[41]

Pressure/temperature

[edit]The steam reforming, shift conversion, carbon dioxide removal, and methanation steps each operate at absolute pressures of about 25 to 35 bar, while the ammonia synthesis loop operates at temperatures of 300–500 °C (572–932 °F) and pressures ranging from 60 to 180 bar depending upon the method used. The resulting ammonia must then be separated from the residual hydrogen and nitrogen at temperatures of −20 °C (−4 °F).[42][3]

Catalysts

[edit]

The Haber–Bosch process relies on catalysts to accelerate N2 hydrogenation. The catalysts are heterogeneous solids that interact with gaseous reagents.[43]

The catalyst typically consists of finely divided iron bound to an iron oxide carrier containing promoters possibly including aluminium oxide, potassium oxide, calcium oxide, potassium hydroxide,[44] molybdenum,[45] and magnesium oxide.

Iron-based catalysts

[edit]The iron catalyst is obtained from finely ground iron powder, which is usually obtained by reduction of high-purity magnetite (Fe3O4). The pulverized iron is oxidized to give magnetite or wüstite (FeO, ferrous oxide) particles of a specific size. The magnetite (or wüstite) particles are then partially reduced, removing some of the oxygen. The resulting catalyst particles consist of a core of magnetite, encased in a shell of wüstite, which in turn is surrounded by an outer shell of metallic iron. The catalyst maintains most of its bulk volume during the reduction, resulting in a highly porous high-surface-area material, which enhances its catalytic effectiveness. Minor components include calcium and aluminium oxides, which support the iron catalyst and help it maintain its surface area. These oxides of Ca, Al, K, and Si are unreactive to reduction by hydrogen.[3]

The production of the catalyst requires a particular melting process in which used raw materials must be free of catalyst poisons and the promoter aggregates must be evenly distributed in the magnetite melt. Rapid cooling of the magnetite, which has an initial temperature of about 3500 °C, produces the desired precursor. Unfortunately, the rapid cooling ultimately forms a catalyst of reduced abrasion resistance. Despite this disadvantage, the method of rapid cooling is often employed.[3]

The reduction of the precursor magnetite to α-iron is carried out directly in the production plant with synthesis gas. The reduction of the magnetite proceeds via the formation of wüstite (FeO) so that particles with a core of magnetite become surrounded by a shell of wüstite. The further reduction of magnetite and wüstite leads to the formation of α-iron, which forms together with the promoters the outer shell.[46] The involved processes are complex and depend on the reduction temperature: At lower temperatures, wüstite disproportionates into an iron phase and a magnetite phase; at higher temperatures, the reduction of the wüstite and magnetite to iron dominates.[47]

The α-iron forms primary crystallites with a diameter of about 30 nanometers. These crystallites form a bimodal pore system with pore diameters of about 10 nanometers (produced by the reduction of the magnetite phase) and of 25 to 50 nanometers (produced by the reduction of the wüstite phase).[46] With the exception of cobalt oxide, the promoters are not reduced.

During the reduction of the iron oxide with synthesis gas, water vapor is formed. This water vapor must be considered for high catalyst quality as contact with the finely divided iron would lead to premature aging of the catalyst through recrystallization, especially in conjunction with high temperatures. The vapor pressure of the water in the gas mixture produced during catalyst formation is thus kept as low as possible, target values are below 3 gm−3. For this reason, the reduction is carried out at high gas exchange, low pressure, and low temperatures. The exothermic nature of the ammonia formation ensures a gradual increase in temperature.[3]

The reduction of fresh, fully oxidized catalyst or precursor to full production capacity takes four to ten days.[3] The wüstite phase is reduced faster and at lower temperatures than the magnetite phase (Fe3O4). After detailed kinetic, microscopic, and X-ray spectroscopic investigations it was shown that wüstite reacts first to metallic iron. This leads to a gradient of iron(II) ions, whereby these diffuse from the magnetite through the wüstite to the particle surface and precipitate there as iron nuclei. A high-activity novel catalyst based on this phenomenon was discovered in the 1980s at the Zhejiang University of Technology and commercialized by 2003.[48]

Pre-reduced, stabilized catalysts occupy a significant market share. They are delivered showing the fully developed pore structure, but have been oxidized again on the surface after manufacture and are therefore no longer pyrophoric. The reactivation of such pre-reduced catalysts requires only 30 to 40 hours instead of several days. In addition to the short start-up time, they have other advantages such as higher water resistance and lower weight.[3]

| Typical catalyst composition[49] | Iron (%) | Potassium (%) | Aluminium (%) | Calcium (%) | Oxygen (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume composition | 40.5 | 0.35 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 53.2 |

| Surface composition before reduction | 8.6 | 36.1 | 10.7 | 4.7 | 40.0 |

| Surface composition after reduction | 11.0 | 27.0 | 17.0 | 4.0 | 41.0 |

Catalysts other than iron

[edit]Many efforts have been made to improve the Haber–Bosch process. Many metals were tested as catalysts. The requirement for suitability is the dissociative adsorption of nitrogen (i. e. the nitrogen molecule must be split into nitrogen atoms upon adsorption). If the binding of the nitrogen is too strong, the catalyst is blocked and the catalytic ability is reduced (self-poisoning). The elements in the periodic table to the left of the iron group show such strong bonds. Further, the formation of surface nitrides makes, for example, chromium catalysts ineffective. Metals to the right of the iron group, in contrast, adsorb nitrogen too weakly for ammonia synthesis. Haber initially used catalysts based on osmium and uranium. Uranium reacts to its nitride during catalysis, while osmium oxide is rare.[50]

According to theoretical and practical studies, improvements over pure iron are limited. The activity of iron catalysts is increased by the inclusion of cobalt.[51]

Ruthenium

[edit]Ruthenium forms highly active catalysts. Allowing milder operating pressures and temperatures, Ru-based materials are referred to as second-generation catalysts. Such catalysts are prepared by the decomposition of triruthenium dodecacarbonyl on graphite.[3] A drawback of activated-carbon-supported ruthenium-based catalysts is the methanation of the support in the presence of hydrogen. Their activity is strongly dependent on the catalyst carrier and the promoters. A wide range of substances can be used as carriers, including carbon, magnesium oxide, aluminium oxide, zeolites, spinels, and boron nitride.[52]

Ruthenium-activated carbon-based catalysts have been used industrially in the KBR Advanced Ammonia Process (KAAP) since 1992.[53] The carbon carrier is partially degraded to methane; however, this can be mitigated by a special treatment of the carbon at 1500 °C, thus prolonging the catalyst lifetime. In addition, the finely dispersed carbon poses a risk of explosion. For these reasons and due to its low acidity, magnesium oxide has proven to be a good choice of carrier. Carriers with acidic properties extract electrons from ruthenium, make it less reactive, and have the undesirable effect of binding ammonia to the surface.[52]

Catalyst poisons

[edit]Catalyst poisons lower catalyst activity. They are usually impurities in the synthesis gas. Permanent poisons cause irreversible loss of catalytic activity, while temporary poisons lower the activity while present. Sulfur compounds, phosphorus compounds, arsenic compounds, and chlorine compounds are permanent poisons. Oxygenic compounds like water, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and oxygen are temporary poisons.[3][54]

Although chemically inert components of the synthesis gas mixture such as noble gases or methane are not strictly poisons, they accumulate through the recycling of the process gases and thus lower the partial pressure of the reactants, which in turn slows conversion.[55]

Industrial production

[edit]Synthesis parameters

[edit]| temperature (°C) | Keq |

|---|---|

| 300 | 4.34 × 10−3 |

| 400 | 1.64 × 10−4 |

| 450 | 4.51 × 10−5 |

| 500 | 1.45 × 10−5 |

| 550 | 5.38 × 10−6 |

| 600 | 2.25 × 10−6 |

The reaction is:

The reaction is an exothermic equilibrium reaction in which the gas volume is reduced. The equilibrium constant Keq of the reaction (see table) and obtained from:

Since the reaction is exothermic, the equilibrium of the reaction shifts at lower temperatures to the ammonia side. Furthermore, four volumetric units of the raw materials produce two volumetric units of ammonia. According to Le Chatelier's principle, higher pressure favours ammonia. High pressure is necessary to ensure sufficient surface coverage of the catalyst with nitrogen.[58] For this reason, a ratio of nitrogen to hydrogen of 1 to 3, a pressure of 250 to 350 bar, a temperature of 450 to 550 °C and α iron are optimal.

The catalyst ferrite (α-Fe) is produced in the reactor by the reduction of magnetite with hydrogen. The catalyst has its highest efficiency at temperatures of about 400 to 500 °C. Even though the catalyst greatly lowers the activation energy for the cleavage of the triple bond of the nitrogen molecule, high temperatures are still required for an appropriate reaction rate. At the industrially used reaction temperature of 450 to 550 °C an optimum between the decomposition of ammonia into the starting materials and the effectiveness of the catalyst is achieved.[59] The formed ammonia is continuously removed from the system. The volume fraction of ammonia in the gas mixture is about 20%.

The inert components, especially the noble gases such as argon, should not exceed a certain content in order not to reduce the partial pressure of the reactants too much. To remove the inert gas components, part of the gas is removed and the argon is separated in a gas separation plant. The extraction of pure argon from the circulating gas is carried out using the Linde process.[60]

Large-scale implementation

[edit]Modern ammonia plants produce more than 3000 tons per day in one production line. The following diagram shows the set-up of a modern (designed in the early 1960s by Kellogg[61]) "single-train" Haber–Bosch plant:

Depending on its origin, the synthesis gas must first be freed from impurities such as hydrogen sulfide or organic sulfur compounds, which act as a catalyst poison. High concentrations of hydrogen sulfide, which occur in synthesis gas from carbonization coke, are removed in a wet cleaning stage such as the sulfosolvan process, while low concentrations are removed by adsorption on activated carbon.[62] Organosulfur compounds are separated by pressure swing adsorption together with carbon dioxide after CO conversion.

To produce hydrogen by steam reforming, methane reacts with water vapor using a nickel oxide-alumina catalyst in the primary reformer to form carbon monoxide and hydrogen. The energy required for this, the enthalpy ΔH, is 206 kJ/mol.[63]

The methane gas reacts in the primary reformer only partially. To increase the hydrogen yield and keep the content of inert components (i. e. methane) as low as possible, the remaining methane gas is converted in a second step with oxygen to hydrogen and carbon monoxide in the secondary reformer. The secondary reformer is supplied with air as the oxygen source. Also, the required nitrogen for the subsequent ammonia synthesis is added to the gas mixture.

In the third step, the carbon monoxide is oxidized to carbon dioxide, which is called CO conversion or water-gas shift reaction.

Carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide would form carbamates with ammonia, which would clog (as solids) pipelines and apparatus within a short time. In the following process step, the carbon dioxide must therefore be removed from the gas mixture. In contrast to carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide can easily be removed from the gas mixture by gas scrubbing with triethanolamine. The gas mixture then still contains methane and noble gases such as argon, which, however, behave inertly.[55]

The gas mixture is then compressed to operating pressure by turbo compressors. The resulting compression heat is dissipated by heat exchangers; it is used to preheat raw gases.

The actual production of ammonia takes place in the ammonia reactor. The first reactors were bursting under high pressure because the atomic hydrogen in the carbonaceous steel partially recombined into methane and produced cracks in the steel. Bosch, therefore, developed tube reactors consisting of a pressure-bearing steel tube in which a low-carbon iron lining tube was inserted and filled with the catalyst. Hydrogen that diffused through the inner steel pipe escaped to the outside via thin holes in the outer steel jacket, the so-called Bosch holes.[57] A disadvantage of the tubular reactors was the relatively high-pressure loss, which had to be applied again by compression. The development of hydrogen-resistant chromium-molybdenum steels made it possible to construct single-walled pipes.[64]

Modern ammonia reactors are designed as multi-storey reactors with a low-pressure drop, in which the catalysts are distributed as fills over about ten storeys one above the other. The gas mixture flows through them one after the other from top to bottom. Cold gas is injected from the side for cooling. A disadvantage of this reactor type is the incomplete conversion of the cold gas mixture in the last catalyst bed.[64]

Alternatively, the reaction mixture between the catalyst layers is cooled using heat exchangers, whereby the hydrogen-nitrogen mixture is preheated to the reaction temperature. Reactors of this type have three catalyst beds. In addition to good temperature control, this reactor type has the advantage of better conversion of the raw material gases compared to reactors with cold gas injection.

Uhde has developed and is using an ammonia converter with three radial flow catalyst beds and two internal heat exchangers instead of axial flow catalyst beds. This further reduces the pressure drop in the converter.[65]

The reaction product is continuously removed for maximum yield. The gas mixture is cooled to 450 °C in a heat exchanger using water, freshly supplied gases, and other process streams. The ammonia also condenses and is separated in a pressure separator. Unreacted nitrogen and hydrogen are then compressed back to the process by a circulating gas compressor, supplemented with fresh gas, and fed to the reactor.[64] In a subsequent distillation, the product ammonia is purified.

Mechanism

[edit]Elementary steps

[edit]The mechanism of ammonia synthesis contains the following seven elementary steps:

- transport of the reactants from the gas phase through the boundary layer to the surface of the catalyst.

- pore diffusion to the reaction center

- adsorption of reactants

- reaction

- desorption of product

- transport of the product through the pore system back to the surface

- transport of the product into the gas phase

Transport and diffusion (the first and last two steps) are fast compared to adsorption, reaction, and desorption because of the shell structure of the catalyst. It is known from various investigations that the rate-determining step of the ammonia synthesis is the dissociation of nitrogen.[3] In contrast, exchange reactions between hydrogen and deuterium on the Haber–Bosch catalysts still take place at temperatures of −196 °C (−320.8 °F) at a measurable rate; the exchange between deuterium and hydrogen on the ammonia molecule also takes place at room temperature. Since the adsorption of both molecules is rapid, it cannot determine the speed of ammonia synthesis.[66]

In addition to the reaction conditions, the adsorption of nitrogen on the catalyst surface depends on the microscopic structure of the catalyst surface. Iron has different crystal surfaces, whose reactivity is very different. The Fe(111) and Fe(211) surfaces have by far the highest activity. The explanation for this is that only these surfaces have so-called C7 sites – these are iron atoms with seven closest neighbours.[3]

The dissociative adsorption of nitrogen on the surface follows the following scheme, where S* symbolizes an iron atom on the surface of the catalyst:[46]

- N2 → S*–N2 (γ-species) → S*–N2–S* (α-species) → 2 S*–N (β-species, surface nitride)

The adsorption of nitrogen is similar to the chemisorption of carbon monoxide. On a Fe(111) surface, the adsorption of nitrogen first leads to an adsorbed γ-species with an adsorption energy of 24 kJmol−1 and an N-N stretch vibration of 2100 cm−1. Since the nitrogen is isoelectronic to carbon monoxide, it adsorbs in an on-end configuration in which the molecule is bound perpendicular to the metal surface at one nitrogen atom.[19][67][3] This has been confirmed by photoelectron spectroscopy.[68]

Ab-initio-MO calculations have shown that, in addition to the σ binding of the free electron pair of nitrogen to the metal, there is a π binding from the d orbitals of the metal to the π* orbitals of nitrogen, which strengthens the iron-nitrogen bond. The nitrogen in the α state is more strongly bound with 31 kJmol−1. The resulting N–N bond weakening could be experimentally confirmed by a reduction of the wave numbers of the N–N stretching oscillation to 1490 cm−1.[67]

Further heating of the Fe(111) area covered by α-N2 leads to both desorption and the emergence of a new band at 450 cm−1. This represents a metal-nitrogen oscillation, the β state. A comparison with vibration spectra of complex compounds allows the conclusion that the N2 molecule is bound "side-on", with an N atom in contact with a C7 site. This structure is called "surface nitride". The surface nitride is very strongly bound to the surface.[68] Hydrogen atoms (Hads), which are very mobile on the catalyst surface, quickly combine with it.

Infrared spectroscopically detected surface imides (NHad), surface amides (NH2,ad) and surface ammoniacates (NH3,ad) are formed, the latter decay under NH3 release (desorption).[57] The individual molecules were identified or assigned by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), high-resolution electron energy loss spectroscopy (HREELS) and Ir Spectroscopy.

On the basis of these experimental findings, the reaction mechanism is believed to involve the following steps (see also figure):[69]

- N2 (g) → N2 (adsorbed)

- N2 (adsorbed) → 2 N (adsorbed)

- H2 (g) → H2 (adsorbed)

- H2 (adsorbed) → 2 H (adsorbed)

- N (adsorbed) + 3 H (adsorbed) → NH3 (adsorbed)

- NH3 (adsorbed) → NH3 (g)

Reaction 5 occurs in three steps, forming NH, NH2, and then NH3. Experimental evidence points to reaction 2 as being the slow, rate-determining step. This is not unexpected, since that step breaks the nitrogen triple bond, the strongest of the bonds broken in the process.

As with all Haber–Bosch catalysts, nitrogen dissociation is the rate-determining step for ruthenium-activated carbon catalysts. The active center for ruthenium is a so-called B5 site, a 5-fold coordinated position on the Ru(0001) surface where two ruthenium atoms form a step edge with three ruthenium atoms on the Ru(0001) surface.[70] The number of B5 sites depends on the size and shape of the ruthenium particles, the ruthenium precursor and the amount of ruthenium used.[52] The reinforcing effect of the basic carrier used in the ruthenium catalyst is similar to the promoter effect of alkali metals used in the iron catalyst.[52]

Energy diagram

[edit]

An energy diagram can be created based on the Enthalpy of Reaction of the individual steps. The energy diagram can be used to compare homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions: Due to the high activation energy of the dissociation of nitrogen, the homogeneous gas phase reaction is not realizable. The catalyst avoids this problem as the energy gain resulting from the binding of nitrogen atoms to the catalyst surface overcompensates for the necessary dissociation energy so that the reaction is finally exothermic. Nevertheless, the dissociative adsorption of nitrogen remains the rate-determining step: not because of the activation energy, but mainly because of the unfavorable pre-exponential factor of the rate constant. Although hydrogenation is endothermic, this energy can easily be applied by the reaction temperature (about 700 K).[3]

Economic and environmental aspects

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

When first invented, the Haber process competed against another industrial process, the cyanamide process. However, the cyanamide process consumed large amounts of electrical power and was more labor-intensive than the Haber process.[5]: 137–143

As of 2018, the Haber process produced 230 million tonnes of anhydrous ammonia per year.[71] The ammonia is used mainly as a nitrogen fertilizer as ammonia itself, in the form of ammonium nitrate, and as urea. The Haber process consumes 3–5% of the world's natural gas production (around 1–2% of the world's energy supply).[4][72][73][74] In combination with advances in breeding, herbicides, and pesticides, these fertilizers have helped to increase the productivity of agricultural land:

With average crop yields remaining at the 1900 level the crop harvest in the year 2000 would have required nearly four times more land and the cultivated area would have claimed nearly half of all ice-free continents, rather than under 15% of the total land area that is required today.[75]

— Vaclav Smil, Nitrogen cycle and world food production, Volume 2, pages 9–13

The energy-intensity of the process contributes to climate change and other environmental problems such as the leaching of nitrates into groundwater, rivers, ponds, and lakes; expanding dead zones in coastal ocean waters, resulting from recurrent eutrophication; atmospheric deposition of nitrates and ammonia affecting natural ecosystems; higher emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), now the third most important greenhouse gas following CO2 and CH4.[75] The Haber–Bosch process is one of the largest contributors to a buildup of reactive nitrogen in the biosphere, causing an anthropogenic disruption to the nitrogen cycle.[76]

Since nitrogen use efficiency is typically less than 50%,[77] farm runoff from heavy use of fixed industrial nitrogen disrupts biological habitats.[4][78]

Nearly 50% of the nitrogen found in human tissues originated from the Haber–Bosch process.[79] Thus, the Haber process serves as the "detonator of the population explosion", enabling the global population to increase from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 7.7 billion by November 2018.[80]

Reverse fuel cell[81] technology converts electric energy, water and nitrogen into ammonia without a separate hydrogen electrolysis process.[82]

The use of synthetic nitrogen fertilisers reduces the incentive for farmers to use more sustainable crop rotations which include legumes for their natural nitrogen-fixing ability.

See also

[edit]- Birkeland–Eyde process – Nitrogen fixation process using electrical arcs

- Calcium cyanamide

- Chilean saltpeter – Mineral form of sodium nitrate

- Guano – Excrement of seabirds or bats

- Hydrogen production – Industrial production of molecular hydrogen

- Industrial gas – Gaseous materials produced for use in industry

- Paradas method – Process to extract nitrate from caliche by leaching

- Crop rotation

- Legume

References

[edit]- ^ Habers process chemistry. India: Arihant publications. 2018. p. 264. ISBN 978-93-131-6303-9.

- ^ Appl, M. (1982). "The Haber–Bosch Process and the Development of Chemical Engineering". A Century of Chemical Engineering. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 29–54. ISBN 978-0-306-40895-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Appl, Max (2006). "Ammonia". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_143.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b c Smil, Vaclav (2004). Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production (1st ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT. ISBN 978-0-262-69313-4.

- ^ a b c d e Hager, Thomas (2008). The Alchemy of Air: A Jewish genius, a doomed tycoon, and the scientific discovery that fed the world but fueled the rise of Hitler (1st ed.). New York, New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-35178-4.

- ^ Sittig, Marshall (1979). Fertilizer Industry: Processes, Pollution Control, and Energy Conservation. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Data Corp. ISBN 978-0-8155-0734-5.

- ^ Vandermeer, John (2011). The Ecology of Agroecosystems. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-7637-7153-9.

- ^ James, Laylin K. (1993). Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901–1992 (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8412-2690-6.

- ^ IChemE. "Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch – Feed the World". www.thechemicalengineer.com. Retrieved 7 July 2025.

- ^ Sheppard, Deri (25 January 2017). "Robert Le Rossignol, 1884–1976: Engineer of the 'Haber' process". Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science. 71 (3): 263–296. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2016.0019. PMC 5554788. PMID 31390408.

- ^ Haber, Fritz (1905). Thermodynamik technischer Gasreaktionen [Thermodynamics of technical gas reactions] (in German) (1st ed.). Paderborn: Salzwasser Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86444-842-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Robert Le Rossignol, 1884–1976: Professional Chemist" (PDF), ChemUCL Newsletter, p. 8, 2009, archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2011.

- ^ Bosch, Carl (2 March 1908). U.S. patent 990,191.

- ^ Philip, Phylis Morrison (2001). "Fertile Minds (Book Review of Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production)". American Scientist. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012.

- ^ Brown, GI (2011). Explosives: History with a Bang (1 ed.). The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5696-6.

- ^ "Nobel Award to Haber" (PDF). The New York Times. 3 February 1920. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Bozso, F.; Ertl, G.; Grunze, M.; Weiss, M. (1977). "Interaction of nitrogen with iron surfaces: I. Fe(100) and Fe(111)". Journal of Catalysis. 49 (1): 18–41. doi:10.1016/0021-9517(77)90237-8.

- ^ Imbihl, R.; Behm, R.J.; Ertl, G.; Moritz, W. (December 1982). "The structure of atomic nitrogen adsorbed on Fe(100)". Surface Science. 123 (1): 129–140. Bibcode:1982SurSc.123..129I. doi:10.1016/0039-6028(82)90135-2.

- ^ a b Ertl, G.; Lee, S. B.; Weiss, M. (1982). "Kinetics of nitrogen adsorption on Fe(111)". Surface Science. 114 (2–3): 515–526. Bibcode:1982SurSc.114..515E. doi:10.1016/0039-6028(82)90702-6.

- ^ Ertl, G. (1983). "Primary steps in catalytic synthesis of ammonia". Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology A. 1 (2): 1247–1253. Bibcode:1983JVSTA...1.1247E. doi:10.1116/1.572299.

- ^ "100 years of Thyssenkrupp Uhde". Industrial Solutions. Retrieved 17 June 2025.

- ^ "Electrochemically-produced ammonia could revolutionize food production". 9 July 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

Ammonia manufacturing consumes 1 to 2% of total global energy and is responsible for approximately 3% of global carbon dioxide emissions.

- ^ Song, Yang; Hensley, Dale; Bonnesen, Peter; Liang, Liango; Huang, Jingsong; Baddorf, Arthur; Tschaplinski, Timothy; Engle, Nancy; Wu, Zili; Cullen, David; Meyer, Harry III; Sumpter, Bobby; Rondinone, Adam (2 May 2018). "A physical catalyst for the electrolysis of nitrogen to ammonia". Science Advances. 4 (4) e1700336. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Bibcode:2018SciA....4..336S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700336. PMC 5922794. PMID 29719860. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

Ammonia synthesis consumes 3 to 5% of the world's natural gas, making it a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions.

- ^ "Ammonia". Industrial Efficiency Technology & Measures. 30 April 2013. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Zhao, Fu; Fan, Ying; Zhang, Shaohui; Eichhammer, Wolfgang; Haendel, Michael; Yu, Songmin (1 April 2022). "Exploring pathways to deep de-carbonization and the associated environmental impact in China's ammonia industry". Environmental Research Letters. 17 (4): 045029. Bibcode:2022ERL....17d5029Z. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac614a.

- ^ Kuganathan, Navaratnarajah; Hosono, Hideo; Shluger, Alexander L.; Sushko, Peter V. (January 2014). "Enhanced N2 Dissociation on Ru-Loaded Inorganic Electride". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 136 (6): 2216–2219. Bibcode:2014JAChS.136.2216K. doi:10.1021/ja410925g. PMID 24483141.

- ^ Hara, Michikazu; Kitano, Masaaki; Hosono, Hideo; Sushko, Peter V. (2017). "Ru-Loaded C12A7:e– Electride as a Catalyst for Ammonia Synthesi". ACS Catalysis. 7 (4): 2313–2324. doi:10.1021/acscatal.6b03357.

- ^ "Ajinomoto Co., Inc., UMI, and Tokyo Institute of Technology Professors Establish New Company to Implement the World's First On Site Production of Ammonia". Ajinomoto. 27 April 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ Crolius, Stephen H. (17 December 2020). "Tsubame BHB Launches Joint Evaluation with Mitsubishi Chemical". Ammonia Energy Association. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ Kitano, Masaaki; Kujirai, Jun; Ogasawara, Kiya; Matsuishi, Satoru; Tada, Tomofumi; Abe, Hitoshi; Niwa, Yasuhiro; Hosono, Hideo (2019). "Low-Temperature Synthesis of Perovskite Oxynitride-Hydrides as Ammonia Synthesis Catalysts". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 141 (51): 20344–20353. Bibcode:2019JAChS.14120344K. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b10726. PMID 31755269.

- ^ Wang, Ying; Meyer, Thomas J. (14 March 2019). "A Route to Renewable Energy Triggered by the Haber–Bosch Process". Chem. 5 (3): 496–497. Bibcode:2019Chem....5..496W. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2019.02.021.

- ^ Schneider, Stefan; Bajohr, Siegfried; Graf, Frank; Kolb, Thomas (13 January 2020). "State of the Art of Hydrogen Production via Pyrolysis of Natural Gas". ChemBioEng Reviews. 7 (5): 150–158. doi:10.1002/cben.202000014.

- ^ Kyriakou, V.; Garagounis, I.; Vasileiou, E.; Vourros, A.; Stoukides, M. (May 2017). "Progress in the Electrochemical Synthesis of Ammonia". Catalysis Today. 286: 2–13. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2016.06.014.

- ^ Clark 2013, However, 400–450 °C isn't a low temperature! Rate considerations: The lower the temperature you use, the slower the reaction becomes. A manufacturer is trying to produce as much ammonia as possible per day. It makes no sense to try to achieve an equilibrium mixture which contains a very high proportion of ammonia if it takes several years for the reaction to reach that equilibrium"..

- ^ Clark 2013, "Rate considerations: Increasing the pressure brings the molecules closer together. In this particular instance, it will increase their chances of hitting and sticking to the surface of the catalyst where they can react. The higher the pressure the better in terms of the rate of a gas reaction. Economic considerations: Very high pressures are expensive to produce on two counts. Extremely strong pipes and containment vessels are needed to withstand the very high pressure. That increases capital costs when the plant is built".

- ^ Zhang, Xiaoping; Su, Rui; Li, Jingling; Huang, Liping; Yang, Wenwen; Chingin, Konstantin; Balabin, Roman; Wang, Jingjing; Zhang, Xinglei; Zhu, Weifeng; Huang, Keke; Feng, Shouhua; Chen, Huanwen (2024). "Efficient catalyst-free N2 fixation by water radical cations under ambient conditions". Nature Communications. 15 (1) 1535: 1535. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.1535Z. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-45832-9. PMC 10879522. PMID 38378822.

- ^ "Chemistry of Nitrogen". Compounds. Chem.LibreTexts.org. 5 June 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.[self-published source?]

- ^ Clark 2013, "At each pass of the gases through the reactor, only about 15% of the nitrogen and hydrogen converts to ammonia. (This figure also varies from plant to plant.) By continual recycling of the unreacted nitrogen and hydrogen, the overall conversion is about 98%".

- ^ Brown, Theodore L.; LeMay, H. Eugene Jr.; Bursten, Bruce E. (2006). "Table 15.2". Chemistry: The Central Science (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-109686-8.

- ^ De Alwis Jayasinghe, Dukula; Chen, Yinlin; Li, Jiangnan; Rogacka, Justyna M.; Kippax-Jones, Meredydd; Lu, Wanpeng; Sapchenko, Sergei; Yang, Jinyue; Chansai, Sarayute; Zhou, Tianze; Guo, Lixia; Ma, Yujie; Dong, Longzhang; Polyukhov, Daniil; Shan, Lutong; Han, Yu; Crawshaw, Danielle; Zeng, Xiangdi; Zhu, Zhaodong; Hughes, Lewis; Frogley, Mark D.; Manuel, Pascal; Rudić, Svemir; Cheng, Yongqiang; Hardacre, Christopher; Schröder, Martin; Yang, Sihai (8 November 2024). "A Flexible Phosphonate Metal–Organic Framework for Enhanced Cooperative Ammonia Capture". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 146 (46): 32040–32048. Bibcode:2024JAChS.14632040D. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c12430. PMC 11583364. PMID 39513623.

- ^ Abild-pedersen, Frank; Bligaard, Thomas (January 2014). "Exploring the limits: A low-pressure, low-temperature Haber–Bosch process". Chemical Physics Letters. 598: 108. Bibcode:2014CPL...598..108V. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2014.03.003.

- ^ Koop, Fermin (13 January 2023). "Green ammonia (and fertilizer) may finally be in sight -- and it would be huge". ZME Science. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Mittasch, Alwin (1926). "Bemerkungen zur Katalyse". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series). 59: 13–36. doi:10.1002/cber.19260590103.

- ^ "3.1 Ammonia synthesis". resources.schoolscience.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020.

- ^ Rock, Peter A. (2013). Chemical Thermodynamics. University Science Books. p. 317. ISBN 978-1-891389-32-0.

- ^ a b c Max Appl (2006). "Ammonia". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_143.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Jozwiak, W. K.; Kaczmarek, E. (2007). "Reduction behavior of iron oxides in hydrogen and carbon monoxide atmospheres". Applied Catalysis A: General. 326 (1): 17–27. Bibcode:2007AppCA.326...17J. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2007.03.021.

- ^ Liu, Huazhang; Han, Wenfeng; Huo, Chao; Cen, Yaqing (15 September 2020). "Development and application of wüstite-based ammonia synthesis catalysts". Catalysis Today. SI: Energy and the Environment. 355: 110–127. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2019.10.031.

- ^ Ertl, Gerhard (1983). "Zum Mechanismus der Ammoniak-Synthese". Nachrichten aus Chemie, Technik und Laboratorium (in German). 31 (3): 178–182. doi:10.1002/nadc.19830310307.

- ^ Bowker, Michael (1993). "Promotion in Ammonia Synthesis". Coadsorption, Promoters and Poisons. The Chemical Physics of Solid Surfaces. Vol. 6. pp. 225–268. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-81468-5.50012-1. ISBN 978-0-444-81468-5.

- ^ Tavasoli, Ahmad; Trépanier, Mariane; Malek Abbaslou, Reza M.; Dalai, Ajay K.; Abatzoglou, Nicolas (December 2009). "Fischer–Tropsch synthesis on mono- and bimetallic Co and Fe catalysts supported on carbon nanotubes". Fuel Processing Technology. 90 (12): 1486–1494. Bibcode:2009FuPrT..90.1486T. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2009.07.007.

- ^ a b c d You, Zhixiong; Inazu, Koji; Aika, Ken-ichi; Baba, Toshihide (October 2007). "Electronic and structural promotion of barium hexaaluminate as a ruthenium catalyst support for ammonia synthesis". Journal of Catalysis. 251 (2): 321–331. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2007.08.006.

- ^ Rosowski, F.; Hornung, A.; Hinrichsen, O.; Herein, D.; Muhler, M. (April 1997). "Ruthenium catalysts for ammonia synthesis at high pressures: Preparation, characterization, and power-law kinetics". Applied Catalysis A: General. 151 (2): 443–460. Bibcode:1997AppCA.151..443R. doi:10.1016/S0926-860X(96)00304-3.

- ^ Højlund Nielsen, P. E. (1995). "Poisoning of Ammonia Synthesis Catalysts". Ammonia. pp. 191–198. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-79197-0_5. ISBN 978-3-642-79199-4.

- ^ a b Falbe, Jürgen (1997). Römpp-Lexikon Chemie (H–L). Georg Thieme Verlag. pp. 1644–1646. ISBN 978-3-13-107830-8.

- ^ Brown, Theodore L.; LeMay, H. Eugene; Bursten, Bruce Edward (2003). Brunauer, Linda Sue (ed.). Chemistry the Central Science (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Pakistan Punjab: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-038168-2.

- ^ a b c Holleman, Arnold Frederik; Wiberg, Egon (2001), Wiberg, Nils (ed.), Inorganic Chemistry, translated by Eagleson, Mary; Brewer, William, San Diego/Berlin: Academic Press/De Gruyter, pp. 662–665, ISBN 0-12-352651-5

- ^ Cornils, Boy; Herrmann, Wolfgang A.; Muhler, M.; Wong, C. (2007). Catalysis from A to Z: A Concise Encyclopedia. Verlag Wiley-VCH. p. 31. ISBN 978-3-527-31438-6.

- ^ Fokus Chemie Oberstufe Einführungsphase (in German). Berlin: Cornelsen-Verlag. 2010. p. 79. ISBN 978-3-06-013953-8.

- ^ P. Häussinger u. a.: Noble Gases. In: Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 2006. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_485

- ^ Travis, Anthony S. (2022). "Historiography of the chemical industry: Technologies and products versus corporate history". Bulletin for the History of Chemistry (1): 50–61. doi:10.70359/bhc2022v047p050.

- ^ Leibnitz, E.; Koch, H.; Götze, A. (1961). "Über die drucklose Aufbereitung von Braunkohlenkokereigas auf Starkgas nach dem Girbotol-Verfahren". Journal für Praktische Chemie (in German). 13 (3–4): 215–236. doi:10.1002/prac.19610130315.

- ^ Steinborn, Dirk (2007). Grundlagen der metallorganischen Komplexkatalyse (in German). Wiesbaden: Teubner. pp. 319–321. ISBN 978-3-8351-0088-6.

- ^ a b c Forst, Detlef; Kolb, Maximillian; Roßwag, Helmut (1993). Chemie für Ingenieure (in German). Springer Verlag. pp. 234–238. ISBN 978-3-662-00655-9.

- ^ "Ammoniakkonverter – Düngemittelanlagen". Industrial Solutions (in German). Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Moore, Walter J.; Hummel, Dieter O. (1983). Physikalische Chemie. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 604. ISBN 978-3-11-008554-9.

- ^ a b Lee, S. B.; Weiss, M. (1982). "Adsorption of nitrogen on potassium promoted Fe(111) and (100) surfaces". Surface Science. 114 (2–3): 527–545. Bibcode:1982SurSc.114..527E. doi:10.1016/0039-6028(82)90703-8.

- ^ a b Ertl, Gerhard (2010). Reactions at Solid Surfaces. John Wiley & Sons. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-470-26101-9.

- ^ Wennerström, Håkan; Lidin, Sven. "Scientific Background on the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2007 Chemical Processes on Solid Surfaces" (PDF). Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ^ Gavnholt, Jeppe; Schiøtz, Jakob (2008). "Structure and reactivity of ruthenium nanoparticles". Physical Review B. 77 (3) 035404. Bibcode:2008PhRvB..77c5404G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.77.035404.

- ^ "Ammonia annual production capacity globally 2030". Statista. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "International Energy Outlook 2007". eia.gov. U.S. Energy Information Administration.

- ^ Fertilizer statistics. "Raw material reserves". www.fertilizer.org. International Fertilizer Industry Association. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008.

- ^ Smith, Barry E. (September 2002). "Structure. Nitrogenase reveals its inner secrets". Science. 297 (5587): 1654–1655. doi:10.1126/science.1076659. PMID 12215632.

- ^ a b Smil, Vaclav (2011). "Nitrogen cycle and world food production" (PDF). World Agriculture. 2: 9–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Kanter, David R.; Bartolini, Fabio; Kugelberg, Susanna; Leip, Adrian; Oenema, Oene; Uwizeye, Aimable (2 December 2019). "Nitrogen pollution policy beyond the farm". Nature Food. 1: 27–32. doi:10.1038/s43016-019-0001-5.

- ^ Oenema, O.; Witzke, H. P.; Klimont, Z.; Lesschen, J. P.; Velthof, G. L. (2009). "Integrated assessment of promising measures to decrease nitrogen losses in agriculture in EU-27". Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 133 (3–4): 280–288. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2009.04.025.

- ^ Howarth, R. W. (2008). "Coastal nitrogen pollution: a review of sources and trends globally and regionally". Harmful Algae. 8 (1): 14–20. Bibcode:2008HAlga...8...14H. doi:10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.015.

- ^ Ritter, Steven K. (18 August 2008). "The Haber–Bosch Reaction: An Early Chemical Impact On Sustainability". Chemical & Engineering News. 86 (33).

- ^ Smil, Vaclav (1999). "Detonator of the population explosion". Nature. 400 (6743): 415. Bibcode:1999Natur.400..415S. doi:10.1038/22672.

- ^ "Ammonia—a renewable fuel made from sun, air, and water—could power the globe without carbon". 28 March 2021. doi:10.1126/science.aau7489.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Blain, Loz (3 September 2021). "Green ammonia: The rocky pathway to a new clean fuel". New Atlas. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Clark, Jim (April 2013) [2002]. "The Haber Process". Retrieved 15 December 2018.

External links

[edit]- Smil, Vaclav (1999). "Detonator of the population explosion". Nature. 400 (6743): 415. Bibcode:1999Natur.400..415S. doi:10.1038/22672.

- "Review of "Between Genius and Genocide: The Tragedy of Fritz Haber, Father of Chemical Warfare" (PDF). Daniel Charles.[dead link]

- "The Haber Process". Chemguide.co.uk.

- BASF – Fertilizer out of thin air

- Britannica guide to Nobel Prizes: Fritz Haber

- Haber Process for Ammonia Synthesis

- Schmidhuber, Jürgen. "Haber–Bosch process".

- Nobel e-Museum – Biography of Fritz Haber

- Uses and Production of Ammonia

Haber process

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early Conceptualization and Laboratory Development

The early conceptualization of the Haber process arose from the thermodynamic understanding of the reversible reaction between nitrogen and hydrogen to form ammonia, N₂ + 3H₂ ⇌ 2NH₃, which is exothermic and favors high pressures per Le Chatelier's principle to counter the decrease in moles of gas. Fritz Haber, recognizing the agricultural and industrial imperative to fix atmospheric nitrogen amid guano depletion, began laboratory investigations in 1904 at the University of Karlsruhe, viewing direct synthesis as potentially viable despite prior failures at atmospheric pressure.[11] Initial experiments in 1905 employed iron catalysts at atmospheric pressure and approximately 1000°C, yielding ammonia concentrations of 0.5% to 1.25% by volume in circulated gas mixtures; tests with nickel, calcium, and manganese catalysts indicated the latter's efficacy at reduced temperatures, underscoring kinetic limitations requiring enhanced catalysis. Equilibrium measurements, informed by Walther Nernst's heat theorem, guided subsequent work, with Haber and Robert Le Rossignol conducting trials at up to 30 atmospheres by 1908.[11][12] Securing BASF funding on March 6, 1908, Haber and Le Rossignol engineered a continuous-flow high-pressure system handling 180-200 atmospheres and a 3:1 hydrogen-nitrogen ratio. Early 1909 breakthroughs used finely divided osmium catalyst at 175 bar and 600°C, attaining 8% ammonia by volume; uranium catalysts similarly yielded around 5%.[13][12][11] Haber filed a German patent for the synthesis on October 13, 1908. Laboratory demonstrations to BASF included 1 cm³/min of liquid ammonia on March 26, 1909, culminating in 500-600 grams produced on July 2, 1909, via osmium catalysis, validating scalability potential.[14][13]Industrial Scaling by Carl Bosch

In 1908, Carl Bosch was tasked by BASF to scale Fritz Haber's laboratory ammonia synthesis to industrial production, addressing the limitations of small-scale experiments that relied on rare catalysts like osmium and uranium.[15] The primary challenges included achieving high pressures of 150–250 atmospheres and temperatures of 400–600°C while managing corrosive synthesis gas mixtures of hydrogen and nitrogen, which demanded novel materials and equipment capable of withstanding extreme conditions without failure.[16] Bosch's team developed iron-based catalysts promoted with additives such as alumina and potassium oxide, identified through extensive testing by Alwin Mittasch, enabling economic viability without scarce metals.[17] [15] Engineering innovations under Bosch included forging high-pressure reactors from specialized steel alloys resistant to hydrogen embrittlement and constructing multi-stage compressors to generate the required pressures efficiently.[16] These advancements resolved gas purification issues and catalyst deactivation, transforming the process from a laboratory curiosity into a feasible continuous operation.[15] The culmination was the Oppau plant, operational on September 9, 1913, with an initial capacity of 30 metric tons of ammonia per day, marking the first industrial-scale application of high-pressure catalysis.[17] This facility rapidly ramped up production, supplying nitrogen compounds critical for fertilizers and, during World War I, munitions.[16] Bosch's scaling efforts laid the foundation for global ammonia production, demonstrating that synthetic fixation could compete with natural sources like guano.[18]

Post-World War I Adoption and Global Expansion

Following World War I, the Haber-Bosch process, which had enabled Germany to sustain explosives production despite naval blockades, transitioned from a wartime strategic asset to a foundation for global agricultural self-sufficiency, as nations prioritized domestic fixed-nitrogen sources to mitigate import vulnerabilities exposed by the conflict. BASF, holder of the core patents, initially withheld licensing abroad citing national security imperatives, prompting rival firms and governments to engineer variant high-pressure syntheses building on Haber's equilibrium principles but optimizing for higher yields via elevated pressures up to 600 atmospheres.[19] This reluctance accelerated parallel innovations, such as Italy's Casale process, which achieved its inaugural commercial plant in 1920 near Milan, yielding approximately 10 metric tons of ammonia per day initially.[12] In France, Georges Claude's process, operating at pressures exceeding 1,000 atmospheres, facilitated the startup of the nation's first synthetic ammonia facility in 1922 at Saint-Gobain's site, with early output supporting fertilizer demands amid postwar reconstruction and averting reliance on Chilean sodium nitrate imports that had comprised over 70% of prewar global supply.[12] The United States, motivated by Muscle Shoals nitrate plants originally built for wartime munitions, pursued independent scaling; by 1921, the Nitrogen Engineering Corporation commissioned a pilot-scale Claude-process unit at Niagara Falls, New York, followed by commercial expansions in the mid-1920s that integrated coke gasification for hydrogen, marking the onset of U.S. production capacities reaching 20,000 tons annually by decade's end.[20] The United Kingdom licensed the authentic Haber-Bosch technology from BASF for Imperial Chemical Industries' Billingham complex, operational from 1924 with coke-derived syngas, producing 25,000 tons of ammonia yearly by 1928 to bolster domestic fertilizer output and counterbalance nitrate import disruptions.[21] By 1930, synthetic ammonia accounted for roughly 1% of global fixed nitrogen but expanded rapidly, with facilities in Japan (via Fauser process adaptations) and elsewhere displacing natural sources; total worldwide capacity surged from near-zero outside Germany in 1920 to over 300,000 tons annually, driven by falling energy costs and engineering refinements that halved per-ton hydrogen needs compared to early Oppau operations.[22] This proliferation underscored the process's scalability, as thermodynamic yields improved marginally through promoter-enhanced catalysts, enabling sustained output under 200-300 atmospheres and 400-500°C.[23]Chemical Foundations

Thermodynamic Principles

The Haber process involves the reversible reaction N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g), which is exothermic with a standard enthalpy change ΔH° = -91.8 kJ/mol at 298 K.[24] This negative ΔH° arises from the formation enthalpies of ammonia, reflecting strong N-H bond formation outweighing N≡N and H-H bond breaking. The reaction also exhibits a negative standard entropy change ΔS° ≈ -198 J/mol·K, primarily due to the reduction in gaseous moles from four to two, decreasing translational entropy.[25] The standard Gibbs free energy change ΔG° = ΔH° - TΔS° determines spontaneity and the equilibrium constant K via ΔG° = -RT ln K. At 298 K, ΔG° ≈ -33 kJ/mol, yielding a large K favoring products thermodynamically.[26] However, the negative ΔS° causes ΔG° to become less negative and eventually positive with increasing temperature; the temperature where ΔG° = 0 is approximately 465 K, beyond which the reverse endothermic reaction is thermodynamically favored.[27] Consequently, the equilibrium constant K_p, defined as K_p = (P_{NH_3}^2) / (P_{N_2} P_{H_2}^3) in partial pressure units (atm^{-2}), decreases exponentially with temperature according to the van't Hoff equation d(ln K)/dT = ΔH° / RT².[25] Le Chatelier's principle elucidates the response to perturbations: elevating temperature shifts equilibrium toward reactants to absorb heat, reducing ammonia yield, while increasing pressure favors products by countering the volume decrease (Δn = -2).[28] These thermodynamic constraints necessitate a compromise in industrial operation—sufficiently high temperature (typically 673–773 K) for kinetic viability despite lowered K_p (on the order of 10^{-3} to 10^{-4} atm^{-2}), paired with elevated pressure (150–300 atm) to enhance conversion per pass to 10–20%.[29] Unreacted gases are recycled to overcome the inherent equilibrium limitation, prioritizing overall process efficiency over single-pass yield.[26]Kinetic Challenges and Equilibrium Constraints

The ammonia synthesis reaction, N₂ + 3H₂ ⇌ 2NH₃, is exothermic with a standard enthalpy change of approximately -92 kJ/mol and involves a reduction in the number of moles of gas from 4 to 2.[3] These thermodynamic properties impose equilibrium constraints: lower temperatures favor higher ammonia yields per Le Chatelier's principle by shifting the equilibrium toward products, yet practical yields diminish rapidly with rising temperature due to the decreasing equilibrium constant K_p. At 450°C and 200 bar, single-pass conversions typically reach only 10-20%, necessitating unreacted gas recycling to achieve overall efficiencies exceeding 98%.[30][31] Kinetic challenges arise primarily from the strong N≡N triple bond in nitrogen, requiring substantial activation energy for dissociation, the rate-determining step on iron catalysts, estimated at 180 kJ/mol.[32] Without catalysis, the reaction proceeds negligibly at ambient conditions; even with promoted iron catalysts, rates remain low, modeled by Temkin equations where nitrogen adsorption dominates, yielding ammonia synthesis rates of about 10-15% per pass under industrial conditions of 400-500°C and 150-300 bar.[33][31] High temperatures are thus employed to accelerate kinetics despite compromising equilibrium, with catalysts lowering the dissociation barrier through surface-mediated mechanisms, though persistent mass transport limitations and catalyst poisoning further complicate achieving optimal rates.[34][35] Balancing these constraints defines Haber-Bosch operation: pressures of 200-300 bar enhance both equilibrium position and collision frequency, while temperatures around 450°C provide a compromise, supported by empirical data showing maximal productivity at this intersection.[3] Advanced kinetic models, such as Langmuir-Hinshelwood frameworks, confirm nitrogen activation as the bottleneck, informing promoter additions like K₂O and Al₂O₃ to modulate adsorption energies and boost turnover frequencies by factors of 2-5.[36] Ongoing research targets single-atom catalysts or nanostructures to further mitigate these barriers, potentially enabling lower-temperature operation without yield penalties.[6]Core Process

Feedstock Preparation

The primary feedstocks for the Haber-Bosch process are nitrogen and hydrogen, combined in a molar ratio of approximately 1:3. Nitrogen is sourced from atmospheric air, which comprises about 78% N₂ by volume, and is separated using cryogenic air separation units (ASUs) in most modern plants. In these units, ambient air is filtered to remove particulates and hydrocarbons, compressed to 5-10 bar, cooled via heat exchangers, and purified further by molecular sieve adsorption to eliminate water vapor, CO₂, and trace impurities; the precooled air is then expanded and liquefied at temperatures near -196°C before fractional distillation in a double-column system yields nitrogen at purities exceeding 99.999%.[17] Pressure swing adsorption (PSA) serves as an alternative for smaller-scale or integrated operations, achieving similar purities through cyclic pressure variations over zeolite or carbon molecular sieve adsorbents, though cryogenic methods dominate large-scale production due to higher efficiency and oxygen byproduct recovery.[37] Hydrogen production, which constitutes the more complex and energy-intensive aspect of feedstock preparation, relies predominantly on steam reforming of natural gas, accounting for roughly 72% of global ammonia capacity as of 2016. Natural gas feedstock is first desulfurized via zinc oxide beds to reduce sulfur content below 0.1 ppm, preventing poisoning of downstream catalysts; it then undergoes primary steam reforming in nickel-based tubes at 800-900°C and 20-30 bar, converting methane primarily to CO and H₂ via CH₄ + H₂O ⇌ CO + 3H₂. A secondary reformer introduces controlled combustion air (adding nitrogen and partial oxidation) to adjust the H₂:N₂ ratio and further convert hydrocarbons, followed by high- and low-temperature water-gas shift reactors (Fe-Cr and Cu-Zn catalysts, respectively) to maximize hydrogen yield through CO + H₂O ⇌ CO₂ + H₂, achieving up to 98% conversion.[17][38] The shifted syngas is then purified: CO₂ is removed by absorption in aqueous amine solutions (e.g., activated methyl diethanolamine), traces of CO and CO₂ are eliminated via methanation (CO + 3H₂ → CH₄ + H₂O over Ni catalyst) or PSA to levels below 10 ppm, and final dehydration ensures moisture content under 5 ppm, yielding hydrogen purity of 97-99% before mixing with nitrogen.[38][12] In coal-dependent regions, such as parts of China representing about 25% of global production, hydrogen derives from gasification of coal or coke with steam and oxygen at 1200-1500°C, producing raw syngas (CO + H₂) that requires extensive cleanup including sour water-gas shift, acid gas removal via physical solvents like Rectisol (cold methanol absorption), and trace contaminant removal to match natural gas-derived specifications.[17] Overall, feedstock preparation emphasizes impurity control—oxygen <1 ppm, argon <1% tolerated as inert—to safeguard the sensitive iron catalyst in the synthesis loop, with integrated plants often recycling purge streams to minimize losses.[37][38]Nitrogen Fixation Reaction

The nitrogen fixation reaction in the Haber process is the catalytic combination of dinitrogen and dihydrogen to form ammonia according to the stoichiometric equation .[3] This reversible reaction fixes atmospheric nitrogen by breaking the strong N≡N triple bond (bond dissociation energy of 941 kJ/mol) and forming N-H bonds, enabling the incorporation of nitrogen into fertilizers and other compounds.[39] The reaction is exothermic, with a standard enthalpy change kJ for the forward direction as written, releasing heat and reducing the number of gas moles from 4 to 2.[40] Thermodynamically, equilibrium conversion increases with pressure and decreases with temperature, but the activation energy for N₂ dissociation—identified as the rate-determining step—necessitates elevated temperatures (typically 400–500°C) to achieve practical rates despite the entropy decrease disfavoring the forward reaction.[41][39] In industrial operation, unreacted gases are recycled to maximize yield, as single-pass conversion remains low (around 10–20%) due to equilibrium limitations under optimized conditions of 150–300 bar pressure.[3] The process thus achieves overall efficiencies exceeding 98% through continuous looping, underscoring the reaction's role in scaling nitrogen fixation from laboratory to global production levels exceeding 150 million metric tons of ammonia annually as of recent estimates.[12]Product Separation and Recycling

In the Haber-Bosch process, the effluent from the synthesis reactor consists of ammonia vapor (typically 15–20% by volume), unreacted nitrogen and hydrogen, and trace inerts such as argon and methane.[17] This mixture, exiting at temperatures of 400–500°C and pressures of 150–300 bar, is first cooled in heat exchangers to recover process heat, reducing the temperature to approximately 40°C using cooling water.[12] Further refrigeration, often via a compressor-chiller system, lowers the temperature to around –5°C or below, enabling partial condensation of ammonia due to its higher boiling point under synthesis pressure compared to the reactant gases.[17] The cooled stream enters a high-pressure separator where liquid ammonia is gravitationally separated from the remaining vapor phase containing predominantly unreacted N₂ and H₂.[17] The liquid ammonia, with purity exceeding 99%, is throttled to atmospheric pressure, flashed to remove dissolved gases, and stored or directed to downstream uses such as urea production or refrigeration.[42] Recovery efficiency in this step approaches 99%, minimizing ammonia losses while exploiting the reversible equilibrium's low single-pass conversion (10–20%).[17] Unreacted gases from the separator are compressed via a circulator (typically centrifugal) to maintain loop pressure and mixed with fresh synthesis gas to restore the 3:1 H₂:N₂ stoichiometry.[12] This closed-loop recycling, pioneered by Haber to overcome thermodynamic limitations, achieves near-complete overall conversion by repeatedly exposing reactants to the catalyst.[12] To prevent accumulation of inerts—which dilute reactants and reduce partial pressures—a purge stream (1–5% of recycle flow) is withdrawn upstream of the circulator; hydrogen is recovered from this purge via pressure swing adsorption (PSA) or cryogenic methods before flaring or reforming.[17] Inert levels are controlled below 10–15 mol% to sustain catalyst activity and equilibrium favorability.[17]Operating Conditions

Pressure and Temperature Optimization

The optimization of pressure and temperature in the Haber-Bosch process arises from the need to reconcile thermodynamic equilibrium limitations with kinetic rate requirements for the exothermic ammonia synthesis reaction (N₂ + 3H₂ ⇌ 2NH₃, ΔH ≈ -92 kJ/mol). Thermodynamically, low temperatures favor higher equilibrium constants and ammonia yields due to the exothermic nature, but practical rates are negligible below 300°C without catalysts, as the activation energy barrier exceeds 100 kJ/mol for nitrogen dissociation. Elevated temperatures of 400–500°C accelerate kinetics via Arrhenius dependence, enabling industrially viable rates with iron-based catalysts, though this reduces equilibrium conversions to 10–20% per pass at typical conditions, necessitating unreacted gas recycle.[25][43] High pressures counteract the thermodynamic penalty of high temperatures by shifting equilibrium toward products per Le Chatelier's principle, as the reaction decreases moles of gas (Δn = -2); for example, at 450°C, equilibrium yield rises from ~5% at 1 bar to over 30% at 200 bar. Industrial operations thus employ 150–300 bar to balance yield gains against compression energy costs (proportional to P ln P) and mechanical stresses on reactors, which require thick-walled alloys to withstand forces exceeding 20,000 psi.[9][29] Process variants reflect ongoing optimization: early 20th-century plants used 200–250 bar for robust yields, while post-1960s low-pressure designs (e.g., 100–150 bar) leverage advanced promoters and quench cooling to sustain rates, reducing capital costs by up to 30% despite slightly lower single-pass efficiency compensated by higher throughput. These conditions yield overall plant efficiencies where temperature primarily governs catalyst activity and side reactions (e.g., methanation), while pressure influences partial pressures in rate laws like the Temkin equation, where rate ∝ P_{N_2}^{0.5} (P_{H_2}^3 / P_{NH_3}^2)^{a}, optimizing net ammonia output.[37][33]Reactor Design Variations

Reactor designs in the Haber process primarily differ in gas flow patterns and heat removal mechanisms to manage the exothermic reaction, which releases approximately 92 kJ/mol of ammonia formed, necessitating precise temperature control between 400–500°C for kinetic rates while favoring lower temperatures for equilibrium conversion.[44] Early industrial implementations, such as those at BASF's Oppau plant operational from September 1913 with a capacity of 30 tons per day, employed axial-flow reactors with internal cooling coils immersed in the catalyst bed to extract heat via steam generation.[12] Subsequent designs shifted toward radial-flow configurations, where synthesis gas enters perpendicular to the reactor axis and flows inward or outward through annular catalyst beds, minimizing pressure drops—typically below 20 bar across the bed with modern catalysts—and enabling larger reactor diameters up to 4 meters.[45] This evolution, prominent from the 1950s onward, facilitated higher throughputs and adaptation to smaller catalyst particles (6–10 mm), reducing diffusion limitations compared to axial-flow systems that suffer higher axial pressure gradients.[45] Cooling strategies classify reactors into three main types: adiabatic quench-cooled (AQCR), adiabatic indirect-cooled (AICR), and internal direct-cooled (IDCR). AQCRs feature multiple adiabatic catalyst beds (often 3–4) with inter-bed injection of cold feed or recycle gas quenches to dilute and cool the reacting mixture, preventing hotspots and achieving per-pass conversions of 15–25% at 150–300 bar.[44] [46] AICRs use external heat exchangers between adiabatic beds to transfer heat to a coolant, offering better temperature profiles but requiring more complex piping.[44] IDCRs incorporate cooling tubes or surfaces directly within a single or few catalyst beds, promoting near-isothermal operation via boiling water or process streams, though prone to uneven cooling and catalyst bypassing if not designed with radial uniformity.[44] These variations balance capital costs, operational flexibility, and efficiency; for instance, quench designs like the Kellogg radial quench converter, introduced in the 1930s and refined post-World War II, dominate legacy plants due to simplicity and tolerance to load variations, while modern AICRs and IDCRs in licenses from Topsøe or Uhde prioritize energy integration with synthesis gas production.[12] Simulations indicate AQCRs yield slightly lower maximum temperatures (up to 520°C) than IDCRs under identical feeds, influencing catalyst longevity.[44] Hybrid axial-radial flows in some beds further optimize distribution in large-scale units exceeding 2000 tons per day ammonia output.[12]Catalysts

Iron-Based Catalysts and Promoters

The iron-based catalysts employed in the Haber-Bosch process are derived from magnetite (Fe₃O₄) fused with promoter oxides and subsequently reduced in situ to metallic α-iron, which serves as the active phase for nitrogen fixation.[12] This formulation, developed by Alwin Mittasch at BASF between 1909 and 1911 through empirical testing of over 2,500 compositions, enabled the first industrial-scale ammonia production at the Oppau plant in 1913.[12] The promoters are incorporated during the fusion of iron oxides at high temperatures, followed by cooling, crushing, and sizing into particles typically 6-10 mm in diameter to optimize bed packing and gas flow in reactors.[12] Key promoters include alumina (Al₂O₃) at 2-3% by weight, acting as a structural stabilizer that prevents sintering and maintains the Fe(111) crystal facets essential for catalytic activity, and potassium oxide (K₂O) in smaller amounts, functioning as an electronic promoter.[12] Alumina forms spinel phases like FeAl₂O₄, contributing to hierarchical porosity and enhanced surface area post-reduction, while K₂O, which partially converts to mobile KOH species under reaction conditions, lowers the activation energy for N₂ adsorption and facilitates NH₃ desorption by weakening metal-nitrogen bonds.[47] Additional structural promoters such as CaO and SiO₂ further improve resistance to impurities and support overall catalyst longevity, with CaO enhancing porosity and SiO₂ aiding in cementitious binding phases.[47] These multi-promoted iron catalysts achieve ammonia synthesis rates sufficient for large-scale operations at 350-500°C and 35-100 bar, with modern variants occasionally incorporating cobalt for doubled volumetric activity as introduced by ICI in 1984, though the core BASF-derived composition remains dominant due to its proven reliability and cost-effectiveness.[12] The even distribution of promoters across the iron crystallites is critical for uniform performance, as uneven promotion can lead to reduced efficiency and hotspots in the reactor bed.[48]Non-Iron Alternatives