Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

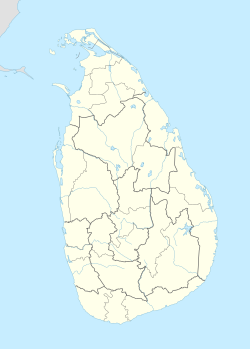

Hambantota

View on WikipediaThe factual accuracy of parts of this article (those related to article) may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (August 2017) |

Hambantota (Sinhala: හම්බන්තොට, Tamil: அம்பாந்தோட்டை) is the main city in Hambantota District, Southern Province, Sri Lanka.

Key Information

This area was hit hard by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and underwent a number of major development projects including the construction of a new sea port and international airport finished in 2013. These projects and others such as Hambantota Cricket Stadium are said to form part of the government's plan to transform Hambantota into the second major urban hub of Sri Lanka, away from Colombo.[1]

History

[edit]When the Kingdom of Ruhuna was established it received many travellers and traders from Siam, China and Indonesia who sought anchorage in the natural harbor at Godawaya, Ambalantota. The ships or large boats these traders travelled in were called "Sampans" and thota means port or anchorage so the port where sampans anchor came to be known as Sampantota. After some time the area came to be called Hambantota.[2]

Hambantota is derived from 'Sampan Thota' – the harbour used by Malay sea going Sampans which traversed the southern seas in the 1400s well before the European colonisers arrived.

The prominent Malay community part of the population is said to be partly descended from seafarers from the Malay Archipelago who travelled through the Magampura port, and over time settled down.

The presence of a pre-existing Malay community prompted the British colonial Government to disband and settle soldiers of a Malay Regiment which had fought with the British in the Kandyan wars at Kirinda near Hambantota. After the arrival of the European colonialists, and the focus of the Galle harbour, Hambantota went into quiet decline.

Ancient Hambantota

[edit]Hambantota District is part of the traditional south known as Ruhuna. In ancient times this region, especially Hambantota and the neighboring areas was the centre of a flourishing civilization. Historical evidence reveals that the region in that era had fertile fields and a stupendous irrigation network. Hambantota was known by many names Mahagama, Ruhuna and Dolos dahas rata.

About 200 BC, the first Kingdom of Sri Lanka was flourishing in the north central region of Anuradhapura.

After a personal dispute with his brother, King Devanampiyatissa of Anuradhapura, King Mahanaga established the Kingdom of Ruhuna in the south of the island. This region played a vital role in building the nation as well as nurturing the Sri Lankan Buddhist culture. Close to Hambantota, the large temple of Tissamaharama was built to house a sacred tooth relic.[3]

Modern history

[edit]Around the years of 1801 and 1803, the British built a Martello tower on the tip of the rocky headland alongside the lighthouse overlooking the sea at Hambantota. The builder was a Captain Goper, who built the tower on the site of an earlier Dutch earthen fort. The tower was restored in 1999, and in the past, formed part of an office of the Hambantota Kachcheri where the Land Registry branch was housed. Today it houses a fisheries museum.

From 2 August to 9 September 1803, an Ensign J. Prendergast of the regiment of Ceylon native infantry was in command of the British colony at Hambantota during a Kandian attack that he was able to repel with the assistance of the snow ship Minerva.[4] Earlier, HMS Wilhelmina had touched there and left off eight men from the Royal Artillery to reinforce him.[5] This detachment participated in Prendergast's successful defense of the colony.[6] If the tower at Hambantota was at all involved in repelling any attack this would be one of the only cases in which a British Martello tower had been involved in combat.

Leonard Woolf, future husband of Virginia Woolf, was the British colonial administrator at Hambantota between 1908 and 1911.

2004 Indian Ocean earthquake

[edit]The 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami devastated Hambantota, and reportedly killed more than 4500 people.[7]

Climate

[edit]Hambantota features a tropical wet and dry climate (As) under the Köppen climate classification. There is no true dry season, but there is significantly less rain from January through March and again from June through August. The heaviest rain falls in October and November. The city sees on average roughly 1,050 millimetres (41 in) of precipitation annually. Average temperatures in Hambantota change little throughout the year, ranging from 26.3 °C (79.3 °F) in January to 28.1 °C (82.6 °F) in April and May.

| Climate data for Hambantota (1991–2020, extremes 1869–2025) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.7 (94.5) |

35.1 (95.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

37.5 (99.5) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.2 (99.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

39.2 (102.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

36.9 (98.4) |

36.7 (98.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

39.2 (102.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.9 (87.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.6 (88.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.4 (86.7) |

31.1 (88.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.1 (80.8) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 68.4 (2.69) |

47.4 (1.87) |

47.0 (1.85) |

92.3 (3.63) |

73.1 (2.88) |

41.2 (1.62) |

30.8 (1.21) |

59.4 (2.34) |

100.0 (3.94) |

128.5 (5.06) |

221.8 (8.73) |

132.1 (5.20) |

1,041.7 (41.01) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.3 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 6.3 | 8.3 | 10.1 | 13.0 | 9.4 | 84.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77 | 78 | 78 | 80 | 81 | 80 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 82 | 81 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 207.7 | 200.6 | 248.0 | 237.0 | 235.6 | 201.0 | 204.6 | 201.5 | 207.0 | 192.2 | 189.0 | 217.0 | 2,541.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.7 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Source 1: NOAA[8] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity, 1950-1994 and sun, 1962–1977),[9] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[10] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]Hambantota Town is Buddhist majority. Islam is the second largest religion in the town. There are also small numbers of Christians and Hindus. Sinhalese people form the majority of the town's population followed by Sri Lankan Malays who make up 30% of the total population.[11]

- Buddhist (81.8%)

- Muslim (16.4%)

- Hindu (0.76%)

- Roman Catholic (0.52%)

- Other Christian (0.44%)

- Other (0.13%)

Economy and infrastructure

[edit]A cement grinding and bagging factory is being set up, as well as fertiliser bagging plants. Large salt plains are a prominent feature of Hambantota. The town is a major producer of salt.[3] A Special Economic Zone of 6,100 hectares (15,000 acres) has been proposed by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, out of which approximately 500 hectares (1,235 acres) will be situated in Hambantota to build factories, LNG plants and refineries while the rest will be in Monaragala, Embilipitiya and Matara.[13][14][15] A Vocational training Center was opened in 2017 by Prime minister Ranil Wickremesinghe with China to train the workforce needed for the SEZs.[16] Wickramasinghe also came into an agreement with state-owned China Merchants Port Holdings to lease 70 per cent stake of the strategically-located Hambantota port at $1.12 billion, opening Hambantota to the Belt and Road Initiative.[17]

Transportation

[edit]Air

[edit]Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport (MRIA) is located in the town of Mattala, 18 km (11 mi) north of Hambantota. Opened in March 2013, it is the second international airport in Sri Lanka after Bandaranaike International Airport in Colombo.[18] The Weerawila Airport is also located nearby.[19]

Road

[edit]A2 highway connects Colombo with Hambantota town through Galle and Matara. The Southern Expressway from Kottawa to Matara will be connected to Hambantota via Beliatta.

Rail

[edit]Construction work started in 2006 on the Matara-Kataragama Railway Line project, a broad gauge railway being implemented at an estimated cost of $91 million.[20]

Energy

[edit]

The Hambantota Wind Farm is the first wind farm in Sri Lanka (there are two more commercial wind farms).[21] It's a pilot project to test wind power generation in the island nation.[22] Wind energy development faces immense obstacles such as poor roads and an unstable power grid. With the transmission network development plan of CEB, first ever 220kV grid substation is under construction in Hambantota, it will be connected to the National Grid by 2022. CHINT Electric is the Main Contractor and Minel Lanka is the National Contractor that carried out design, civil construction and electrical installation works. This substation will be handling 500 MVA with 6 units of 220/132/33 kV 83.33 MVA power transformers from Tirathai.[23]

Port

[edit]

Hambantota is the selected site for a new international port, the Port of Hambantota. It was scheduled to be built in three phases, with the first phase due to be completed by the end of 2010 at a cost of $360 million.[24] As part of the port, a $550 million tax-free port zone is being started, with companies in India, China, Russia and Dubai expressing interest in setting up shipbuilding, ship-repair and warehousing facilities in the zone. The port officially opened on November 18, 2010, at the end of the first phase of construction.[25] When all phases are fully complete, it will be able to berth 33 vessels, which would make it the biggest port in South Asia.[26]

Bunkering facility: 14 tanks (8 for oil, 3 for aviation fuel and 3 for LP gas) with a total capacity of 80,000 m3 (2,800,000 cu ft).[27] But in the whole of 2012 only 34 ships berthed at Hambantota, compared with 3,667 ships at the port of Colombo.[25] Sri Lanka was still heavily in debt to China for the cost of the port and with so little traffic, was unable to service the debt.[28] In 2017 China was given a 99-year lease for the port in exchange for $1.1 billion.[29]

The involvement of Chinese companies in the development of Hambantota port have provoked claims by some analysts that it is part of China's String of Pearls strategy. Other analysts have argued that it would not be in Sri Lanka's interests to allow the Chinese navy access to the port and in any event the exposed nature of the port would make it of dubious value to China in time of conflict.[30]

In November 2019, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa indicated that the Sri Lankan government would try to undo the 99-year lease of the port and return to the original loan repayment schedule.[29][31] As of August 2020 the 99-year lease was still in place.[32]

Culture

[edit]Hambantota contains the Mahinda Rajapaksa International Stadium[33] for sports activities. It has a capacity of 35,000 seats and was built for the 2011 Cricket World Cup. The cost of this project is an estimated Rs. 900 million (US$7.86m). Sri Lanka Cricket is seeking relief from its debts incurred in building infrastructure for the 2011 Cricket World Cup.[1]

Magam Ruhunupura International Conference Hall (MRICH) was built for local and international events. The MRICH, situated in a 28-acre plot of land in Siribopura, is Sri Lanka's second international conference hall. The main hall has 1,500 seats and there are three additional halls with a seating capacity of 250 each. The conference hall is fully equipped with modern technical facilities and a vehicle park for 400 vehicles and a helipad for helicopter landing.[34]

On 31 March 2010, a surprise bid was made for the 2018 Commonwealth Games by Hambantota. Hambantota is undergoing a major face lift since the tsunami. On 10 November 2011, the Hambantota bidders claimed they had already secured enough votes to win the hosting rights.[35] However, on 11 November it was officially announced that Australia's Gold Coast had won the rights to host the games.[36][37]

Twin cities

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Fernando, Andrew Fidel (April 5, 2013). "SLC expects financial assistance from government". ESPNCricinfo. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ "Hambantota". Hambantota District Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Hambantota District. Hambantota: Sri Lanka's Deep South". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- ^ The Asiatic annual register, or, A View of the history of ..., Volume 8, Issue 1, p.74.

- ^ "No. 15689". The London Gazette. 3 April 1804. p. 405.

- ^ Stubbs, Francis W. (January 2010). History of the Organization, Equipment, and War Services of the Regiment of Bengal Artillery. General Books. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-150-23818-5.

- ^ "Divisions over tsunami new town". BBC. 17 March 2005. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Hambantota". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Hambantota / Sri Lanka (Ceylon)" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ "Station Hambantota" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Nordhoff, Sebastian (2012). The Genesis of Sri Lanka Malay: A Case of Extreme Language Contact. Brill Publishers. p. 3.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing 2012". statistics.gov.lk. Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka. 2012.

- ^ "economynext.com". www.economynext.com. Archived from the original on 2018-08-07. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ "Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka launches special industrial zone to attract Chinese industries". Colombo Page. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ "US $ 5 b investment in Hambantota: 1,235 acres for industrial zone". Sunday Observer. 2017-01-07. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ "Sri Lanka, China open training center to support southern development – Xinhua | English.news.cn". news.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ "Hambantota Port agreement to be signed tomorrow - PM".

- ^ "Overview of Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport (MRIA)". www.airport.lk/. Archived from the original on 2018-04-10.

- ^ "(WRZ) Weerawila Airport". FlightStats. Archived from the original on 2016-06-04. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

- ^ Massive Development in Hambantota District Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, Media Centre for National Development in Sri Lanka, retrieved 2010-01-19

- ^ "Sri Lanka's first commercial wind energy plant to start - LANKA BUSINESS ONLINE". Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "3 MW Pilot Wind Power Project at Hambantota". Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "Minel Lanka Projects". Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Shirajiv Sirimane (21 February 2010). "Hambantota port, gateway to world". Sunday Observer. Archived from the original on 24 February 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ a b Abi-Habib, Maria (25 June 2018). "How China Got Sri Lanka to Cough Up a Port". The New York Times. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ Ondaatjie, Anusha (8 March 2010). "Sri Lanka to Seek Tenants for $550 Million Tax-Free Port Zone". Business Week. Archived from the original on March 11, 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ "Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka\'s Hambantota Harbor refuels six ships in two weeks". www.colombopage.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-10.

- ^ Stacey, Kiran (11 December 2017). "China signs 99-year lease on Sri Lanka's Hambantota port". Financial Times. ft.com. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ a b Asantha Sirimanne, Anusha Ondaatjie (30 November 2019). "Sri Lanka leased Hambantota port to China for 99 yrs. Now it wants it back". Business Standard. Business Standard Ltd. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ David Brewster. "Beyond the String of Pearls: Is there really a Security Dilemma in the Indian Ocean?. Retrieved 11 August 2014".

- ^ Ondaatjie, Anusha; Sirimanne, Asantha (28 November 2019). "Sri Lanka Wants to Undo Deal to Lease Port to China for 99 Years". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019.

We would like them to give it back," Ajith Nivard Cabraal, a former central bank governor and an economic adviser to Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, said in an interview at his home in a Colombo suburb. "The ideal situation would be to go back to status quo. We pay back the loan in due course in the way that we had originally agreed without any disturbance at all.

- ^ Saeed Shah, Asiri Fernando (7 August 2020). "Pro-China Populists Consolidate Power in Sri Lanka". The Wall Street Journal. wsj.com. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ "Mahinda Rajapaksa International Cricket Stadium | Sri Lanka | Cricket Grounds | ESPNcricinfo.com". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ^ "President opens international convention center in Hambantota ahead of CHOGM | DailyFT - Be Empowered". www.ft.lk. Archived from the original on 2013-11-11.

- ^ Ardern, Lucy (11 November 2011). "Sri Lanka boasting of Games bid win". Gold Coast Bulletin. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ "Candidate City Manual" (PDF). Commonwealth Games Federation. December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ Ardern, Lucy (13 November 2011). "Coast wins 2018 Commonwealth Games". Gold Coast Bulletin. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ "Guangzhou Sister Cities [via WaybackMachine.com]". Guangzhou Foreign Affairs Office. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- Stubbs, Francis W. (1877) History of the organization, equipment, and war services of the regiment of Bengal artillery : compiled from published works, official records, and various private sources. (Henry S. King & Co.).

External links

[edit]Hambantota

View on GrokipediaHambantota is the principal city and administrative center of Hambantota District in Sri Lanka's Southern Province, situated on the southeastern coast along the Indian Ocean. The district spans 2,609 square kilometers and had an estimated population of 676,089 in 2023, predominantly engaged in agriculture, fishing, and livestock rearing.[1][2] The region has gained prominence for large-scale infrastructure projects initiated during former President Mahinda Rajapaksa's tenure, including the Hambantota International Port and Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport, financed largely through loans from the Export-Import Bank of China. The port's first phase, completed in 2010 with a $307 million loan at 6.3% interest, aimed to handle transshipment cargo but initially operated below capacity, prompting a 99-year lease to China Merchants Port Holdings in 2017 for $1.12 billion to ease debt repayment.[3][4] These developments, intended to transform Hambantota into an economic hub, have sparked debate over their viability and contribution to Sri Lanka's sovereign debt crisis, with critics highlighting underutilization amid high construction costs, though analyses question exaggerated claims of coercive Chinese "debt-trap diplomacy" given that bilateral debt to China constitutes a minority of total external obligations.[5][3] The area also features natural attractions such as Bundala National Park and proximity to Yala National Park, supporting ecotourism and biodiversity conservation.[6]

Geography

Location and physical features

Hambantota District is situated in the southeastern part of Sri Lanka within the Southern Province, bordering the Indian Ocean to the south. It spans an area of 2,609 square kilometers, representing approximately 3.97% of the nation's total land area, and features a coastline extending about 140 kilometers. The district's central coordinates are approximately 6°7' N latitude and 81°8' E longitude.[7][8][9] The terrain of Hambantota District primarily consists of low-lying coastal plains and flat to rolling landscapes characteristic of Sri Lanka's dry zone, with elevations starting at sea level along the shoreline and averaging around 109 meters (358 feet) across the district. Inland areas include gentle slopes and some rolling terrain, though steeper slopes are less common and mainly support limited settlement. The coastal zone features sandy beaches, lagoons such as the Hambantota Lagoon, and scrubland vegetation adapted to semi-arid conditions.[10][11][12] Physical features are shaped by the district's exposure to the Indian Ocean, including dynamic coastal processes like erosion and sediment deposition, which affect low-lying lands vulnerable to inundation. The region's topography supports a mix of agricultural plains and natural wetlands, contributing to its ecological diversity despite water scarcity challenges.[8][13]Climate and environmental conditions

Hambantota experiences a tropical savanna climate (Köppen classification Aw), with consistently warm temperatures and low annual rainfall typical of Sri Lanka's southeastern dry zone. Average daily temperatures hover between 27°C and 29°C throughout the year, with the highest monthly mean of 28.6°C occurring in April and May, and the lowest of 27°C in December. Diurnal variations are minimal due to proximity to the equator, though nighttime lows can dip to 24°C during the drier months. Relative humidity remains high at 75-85%, contributing to a muggy feel, while prevailing winds from the northeast monsoon (October-February) and southwest inter-monsoon (May-September) influence local weather patterns.[14][15] Precipitation totals approximately 1,000-1,200 mm annually, with over 70% concentrated in the short wet season from October to January driven by the northeast monsoon. The remainder of the year features prolonged dry spells, exacerbated by the rain shadow effect of the central highlands, resulting in frequent water scarcity. Evaporation rates exceed rainfall in non-monsoonal periods, amplifying aridity. Data from the Sri Lanka Department of Meteorology's Hambantota station confirm this pattern, with monthly rainfall rarely surpassing 100 mm outside the peak season.[14][16][17] The region's environmental conditions are marked by vulnerability to meteorological and agricultural droughts, with Hambantota district classified among Sri Lanka's most affected areas based on historical records from 1974-2007. Severe droughts, such as the 2016-2017 event—the worst in four decades—affected over a million people nationwide, with acute shortages in Hambantota due to depleted reservoirs and failed crops. These events correlate with El Niño-Southern Oscillation phases, reducing monsoon reliability and leading to soil degradation and salinity intrusion in coastal aquifers. Vegetation consists primarily of drought-resistant thorny scrub, open woodlands, and grasslands adapted to semi-arid conditions, supporting wildlife like elephants and leopards in adjacent reserves, though habitat fragmentation from development poses risks. Climate projections indicate increasing drought frequency under warming scenarios, with potential 20-30% rainfall declines by mid-century.[18][19][20]History

Ancient and pre-colonial periods

The region of modern Hambantota District constituted the heartland of the ancient Kingdom of Ruhuna, a Sinhalese principality that emerged in southern Sri Lanka during the 3rd century BCE and persisted until the 13th century CE.[21] Ruhuna functioned as a strategic refuge for exiled monarchs and a launchpad for rebellions against northern Rajarata kingdoms and foreign invaders, exemplified by Prince Dutugamunu's campaign from Ruhuna, which culminated in the defeat of the Tamil ruler Elara and the restoration of Sinhalese dominance around 161 BCE.[22] This southern domain maintained semi-autonomy amid dynastic shifts, fostering a distinct cultural and political identity rooted in Buddhist monastic traditions and defensive fortifications.[23] Archaeological evidence reveals Ruhuna as a hub of agricultural prosperity, with extensive irrigation networks enabling large-scale rice cultivation and supporting a dense population in fertile coastal plains.[24][25] Sites such as ancient tanks like Buthuwa Wewa demonstrate engineering prowess comparable to northern hydraulic civilizations, sustaining settlements through monsoon-dependent farming from at least the 2nd century BCE.[22] Maritime trade further bolstered the economy, as evidenced by the port at Godawaya near Hambantota, active from the 1st–2nd centuries CE during King Gajabahu I's reign (113–135 CE), where artifacts including Indo-Roman coins indicate customs operations and connections to Indian Ocean networks.[26] Buddhist religious complexes proliferated across Ruhuna, underscoring its role in Sinhalese Theravada heritage, with ruins of stupas, image houses, and limestone Buddha statues at sites like Telulla dating to the Anuradhapura Period (circa 3rd century BCE–10th century CE).[27] Other monuments, including caves and dagobas in the Yala area overlying ancient Ruhuna boundaries, reflect monastic patronage by local rulers, while rock formations like Yahangala served as abodes for arahats in early Buddhist practice.[22][28] These structures highlight a pre-colonial society integrated with continental trade routes yet resilient against incursions, until incorporation into unified Sinhalese polities by the 13th century.[21]Colonial era and early modern developments

The Portuguese, who established control over coastal Sri Lanka from 1505, showed limited interest in the arid Hambantota region compared to spice-rich wet zones, but constructed forts at nearby Bundala to secure the saltpans and disrupt the Muslim monopoly on internal salt trade.[25] The Dutch, supplanting Portuguese rule in coastal areas from 1658 to 1796, maintained these Bundala fortifications and, by 1760, erected a fort at Hambantota itself to safeguard the lucrative salt production and trade in the district.[25][29] British administration began in 1796 following the Dutch capitulation, with the relocation of the district garrison from Bundala to Hambantota and the establishment of key institutions including the Kachcheri revenue office, courthouse, police station, and customs post, formalizing the town as the administrative hub.[30] In response to Kandyan kingdom raids on Hambantota in 1803, the British initiated construction of a Martello tower overlooking the bay, completed under Lieutenant William Gosset of the Royal Engineers starting after September 1804 and progressing by May 1805, as the sole such structure in Sri Lanka designed for coastal defense against bombardment and enemy vessels.[31] Early 19th-century British policy deployed convict laborers to the Hambantota saltpans for extraction tasks, serving both punitive detention and revenue generation through natural evaporation processes in the district's lagoons and pans.[32] A pre-existing Malay community in the area, tracing to earlier traders, influenced British decisions to disband and settle soldiers from the Malay Regiment near Kirinda following the Kandyan conflicts, integrating military veterans into local settlements.[25]Post-independence and civil war impacts

Following independence from Britain on February 4, 1948, Hambantota District underwent a transition in agricultural practices, moving away from traditional swidden (slash-and-burn) cultivation toward more systematic farming, including expanded rice paddy production supported by initial government irrigation enhancements.[33] This shift aligned with national efforts to achieve food self-sufficiency, though the district remained one of Sri Lanka's more underdeveloped regions, with limited infrastructure and persistent rural poverty.[34] In the 1970s, the Norwegian-funded Integrated Rural Development Programme targeted Hambantota, introducing improvements in farming techniques, credit access, and basic infrastructure to boost productivity in dry-zone agriculture.[35] The subsequent Accelerated Mahaweli Development Programme in the 1980s further expanded irrigation networks, enabling cultivation on previously marginal lands and contributing to modest economic growth, though benefits were unevenly distributed amid national economic challenges like import substitution policies.[36] The district experienced limited direct involvement in the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict from 1983 to 2009, as fighting concentrated in the Northern and Eastern Provinces; however, indirect effects included heightened national military conscription drawing from southern youth, inflationary pressures from war expenditures, and disruptions to trade and remittances.[37] More acutely, Hambantota served as a stronghold for the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) during its 1987–1989 insurrection, a Marxist youth-led uprising against the government that engulfed rural southern Sri Lanka.[38] JVP activities in areas like Tissamaharama triggered brutal counterinsurgency responses, including operations by state-backed death squads that resulted in widespread extrajudicial killings; in one instance during December 1988, over 170 bodies were discovered across Hambantota District in a single night, reflecting the scale of state repression.[39] Subsequent discoveries of mass graves, such as in Suriyakanda in 1994, underscored the violence's toll, with estimates of thousands killed nationwide but concentrated in southern districts like Hambantota, leading to social fragmentation, rural depopulation, and long-term trauma that stalled local development initiatives.[38] These events exacerbated ethnic and class tensions, reinforcing Hambantota's image as a politically volatile periphery despite its Sinhalese-Buddhist demographic majority.2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami

The tsunami, generated by a magnitude 9.1–9.3 undersea earthquake off Sumatra on December 26, 2004, struck Hambantota district's southern coastline approximately 2.5 hours later, around 9:00–10:00 a.m. local time.[40] Waves measuring 4 to 6 meters in height surged inland, inundating low-lying coastal areas and causing rapid flooding in fishing villages and towns including Hambantota, Tangalle, and nearby settlements.[41] The lack of an early warning system amplified the devastation, as residents had minimal time to evacuate despite observing the initial sea recession.[42] Hambantota district suffered around 450 confirmed deaths, with the majority among fishermen and coastal dwellers caught by the sudden onslaught; additional injuries and missing persons reports pushed the human toll higher.[43] Property damage was extensive, with thousands of homes, schools, and other structures flattened or washed away, fishing fleets decimated by capsized boats, and the local lagoon contaminated by debris and saltwater intrusion.[44] [45] This crippled the district's primary livelihoods in fisheries and small-scale agriculture, displacing several thousand residents into temporary shelters amid disrupted water, sanitation, and transport infrastructure.[46] The disaster highlighted vulnerabilities in Hambantota, a relatively impoverished region with limited preparedness, though local community responses provided initial aid before international organizations mobilized reconstruction support.[46] Long-term effects included altered coastal ecosystems and ongoing trauma for survivors, contributing to shifts in settlement patterns and economic diversification efforts in the district.[43]Government and administration

Local governance structure

Hambantota District's local governance operates within Sri Lanka's decentralized system, featuring elected local authorities responsible for urban and rural administration, coordinated by the District Secretariat. The district includes one municipal council, one urban council, and multiple pradeshiya sabhas (rural local councils), which handle services such as sanitation, local infrastructure maintenance, public health, and licensing.[47][48] The Hambantota Municipal Council governs the capital's urban core, encompassing approximately 50 square kilometers and serving over 100,000 residents as of recent estimates; it is led by a mayor and council members elected every four years.[49][50] The Tangalle Urban Council manages the coastal town of Tangalle and its immediate environs, focusing on tourism-related infrastructure and environmental regulation.[47] Pradeshiya sabhas cover the district's rural divisions, including Ambalantota, Angunukolapalassa, Beliatta, Hambantota, Katuwana, Tangalle, and Weeraketiya; these bodies, each with elected chairpersons and members, address agriculture support, rural roads, and community welfare in their jurisdictions.[49][48] For instance, the Hambantota Pradeshiya Sabha operates alongside the municipal council to serve peri-urban areas.[51] Overarching coordination falls to the District Secretariat, headed by a centrally appointed District Secretary, which subdivides the district into 13 divisional secretariats (as of 2023 data) for implementing national policies, revenue collection, and inter-agency liaison; beneath these are over 500 Grama Niladhari divisions for grassroots administration.[1] All local authorities report to the Ministry of Provincial Councils and Local Government, with elections last held in 2018 and subsequent polls in 2025 determining current compositions.[52][53]Political significance and influence

Hambantota District serves as the political stronghold of the Rajapaksa family, which has exerted dominant influence over Sri Lankan politics for decades, particularly in the southern region. Mahinda Rajapaksa, born on December 18, 1945, in Medamulana village within the district, entered politics representing local electorates such as Beliatta, building a base among the Sinhalese rural population through patronage and development promises.[54][55] The family's grip strengthened post-2005, when Mahinda's presidency aligned national policy with regional favoritism, channeling resources to Hambantota to consolidate voter loyalty despite broader economic critiques of inefficiency.[4][56] Under Mahinda Rajapaksa's administration from 2005 to 2015, the district became emblematic of executive-driven infrastructure expansion, including the Hambantota Port (commissioned in November 2010 with $360 million in Chinese loans), Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport (opened in March 2013), and a conference hall renamed Magampura Mahinda Rajapaksa Port City. These projects, totaling billions in foreign borrowing—predominantly from China—prioritized Hambantota over more viable sites like Colombo, fostering accusations of nepotism as the district accounted for a disproportionate share of post-civil war investments.[57][56][58] Economic underperformance ensued, with the port handling minimal traffic and the airport dubbed the "world's emptiest" by 2018, exacerbating Sri Lanka's debt burden that culminated in the 2017 99-year lease of 70% of the port to China Merchants Port Holdings for $1.12 billion in debt relief.[56][57] Electorally, Hambantota has reliably backed Rajapaksa-aligned parties, reflecting familial entrenchment; family members like Namal Rajapaksa held parliamentary seats from the district until recent shifts. In the 2020 parliamentary elections, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), founded by the Rajapaksas, secured strong majorities in southern districts including Hambantota, mirroring patterns from 2010 when Mahinda garnered over 60% district-wide presidential support.[59][60] However, the 2022 economic crisis eroded this base, with protests in Hambantota targeting Rajapaksa symbols amid perceptions of elite capture, leading to SLPP setbacks in subsequent local polls.[61][62] This volatility underscores Hambantota's role as a bellwether for dynastic politics, where local development promises intersect with national fiscal realities.[59]Demographics

Population composition and trends

As of the 2012 Census of Population and Housing, the Hambantota District recorded a total population of 599,903 residents. Mid-year estimates from the Department of Census and Statistics project the population at approximately 680,000 in 2024, reflecting steady growth from 618,000 in 2014 to a peak around 681,000 in 2022 before stabilizing amid national economic challenges. This represents an average annual growth rate of about 1.0% from 2012 to 2020, exceeding Sri Lanka's national rate of 0.5-0.7% during the same period, partly due to infrastructure projects like port expansion drawing internal migrants from other districts.[63][64] The district maintains a sex ratio of roughly 97 males per 100 females, consistent across the 2012 census and recent mid-year projections (e.g., 334,000 males and 346,000 females in 2024 estimates). Population density stands at about 260 persons per square kilometer over the district's 2,609 km² area, with over 94% of residents in rural areas as of 2021 estimates, indicating limited urbanization despite planned developments in the Hambantota urban zone.[63][64][65] Age structure data from the 2012 census reveals a relatively youthful profile, with 25.8% under 15 years, 66.8% aged 15-64, and 7.4% over 65, though national trends suggest gradual aging due to declining fertility rates below replacement level. Detailed breakdowns include:| Age Group | Population (2012) |

|---|---|

| 0-9 years | 108,980 |

| 10-19 years | 94,621 |

| 20-29 years | 91,588 |

| 30-39 years | 87,453 |

| 40-49 years | 75,557 |

| 50-59 years | 67,108 |

| 60+ years | 74,596 |

Ethnic and religious distribution

The 2012 Census of Population and Housing recorded Hambantota District's total population at 599,903, with Sinhalese comprising the overwhelming majority at 97.1% (582,301 individuals).[66] Minority ethnic groups include Burghers at 1.4% (8,164), Sri Lankan Moors at 1.1% (6,629), Sri Lankan Tamils at 0.4% (2,105), Bharatha at 0.07% (418), Indian Moors at 0.02% (146), and Indian Tamils at 0.02% (120), alongside negligible numbers of Malays (17) and Sri Lankan Chetties (3).[66]| Ethnic Group | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sinhalese | 582,301 | 97.1% |

| Burgher | 8,164 | 1.4% |

| Sri Lankan Moor | 6,629 | 1.1% |

| Sri Lankan Tamil | 2,105 | 0.4% |

| Bharatha | 418 | 0.07% |

| Indian Moor | 146 | 0.02% |

| Indian Tamil | 120 | 0.02% |

| Other (incl. Malay, Chetty) | 20 | <0.01% |

| Religion | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Buddhist | 580,344 | 96.8% |

| Islam | 15,204 | 2.5% |

| Other Christian | 1,692 | 0.3% |

| Roman Catholic | 1,139 | 0.2% |

| Hindu | 1,222 | 0.2% |

| Other | 302 | 0.05% |