Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dangerous goods

View on Wikipedia

Dangerous goods are substances that are a risk to health, safety, property or the environment during transport. Certain dangerous goods that pose risks even when not being transported are known as hazardous materials (syllabically abbreviated as HAZMAT or hazmat). An example of dangerous goods is hazardous waste which is waste that threatens public health or the environment.[1]

Hazardous materials are often subject to chemical regulations. Hazmat teams are personnel specially trained to handle dangerous goods, which include materials that are radioactive, flammable, explosive, corrosive, oxidizing, asphyxiating, biohazardous, toxic, poisonous, pathogenic, or allergenic. Also included are physical conditions such as compressed gases and liquids or hot materials, including all goods containing such materials or chemicals, or may have other characteristics that render them hazardous in specific circumstances.

Dangerous goods are often indicated by diamond-shaped signage on the item (see NFPA 704), its container, or the building where it is stored. The color of each diamond indicates its hazard, e.g., flammable is indicated with red, because fire and heat are generally of red color, and explosive is indicated with orange, because mixing red (flammable) with yellow (oxidizing agent) creates orange. A nonflammable and nontoxic gas is indicated with green, because all compressed air vessels were this color in France after World War II, and France was where the diamond system of hazmat identification originated.

Global regulations

[edit]The most widely applied regulatory scheme is that for the transportation of dangerous goods. The United Nations Economic and Social Council issues the UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, which form the basis for most regional, national, and international regulatory schemes. For instance, the International Civil Aviation Organization has developed dangerous goods regulations for air transport of hazardous materials that are based upon the UN model but modified to accommodate unique aspects of air transport. Individual airline and governmental requirements are incorporated with this by the International Air Transport Association to produce the widely used IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR).[2] Similarly, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has developed the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code ("IMDG Code", part of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea) for transportation of dangerous goods by sea. IMO member countries have also developed the HNS Convention to provide compensation in case of dangerous goods spills in the sea.

The Intergovernmental Organisation for International Carriage by Rail has developed the regulations concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Rail ("RID", part of the Convention concerning International Carriage by Rail). Many individual nations have also structured their dangerous goods transportation regulations to harmonize with the UN model in organization as well as in specific requirements.

The Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) is an internationally agreed upon system set to replace the various classification and labeling standards used in different countries. The GHS uses consistent criteria for classification and labeling on a global level.

UN numbers and proper shipping names

[edit]Dangerous goods are assigned to UN numbers and proper shipping names according to their hazard classification and their composition. Dangerous goods commonly carried are listed in the Dangerous Goods list.[3]

Examples for UN numbers and proper shipping names are:

- 1202 GAS OIL or DIESEL FUEL or HEATING OIL, LIGHT

- 1203 MOTOR SPIRIT or GASOLINE or PETROL

- 3090 LITHIUM METAL BATTERIES

- 3480 LITHIUM ION BATTERIES including lithium ion polymer batteries

Classification and labeling summary tables

[edit]Dangerous goods are divided into nine classes (in addition to several subcategories) on the basis of the specific chemical characteristics producing the risk.[4]

Note: The graphics and text in this article representing the dangerous goods safety marks are derived from the United Nations-based system of identifying dangerous goods. Not all countries use precisely the same graphics (label, placard or text information) in their national regulations. Some use graphic symbols, but without English wording or with similar wording in their national language. Refer to the dangerous goods transportation regulations of the country of interest.

For example, see the TDG Bulletin: Dangerous Goods Safety Marks[5] based on the Canadian Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations.

The statement above applies equally to all the dangerous goods classes discussed in this article.

| Class 1: Explosives | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information on this graphic changes depending on which, "Division" of explosive is shipped. Explosive Dangerous Goods have compatibility group letters assigned to facilitate segregation during transport. The letters used range from A to S excluding the letters I, M, O, P, Q and R. The example above shows an explosive with a compatibility group "A" (shown as 1.1A). The actual letter shown would depend on the specific properties of the substance being transported.

For example, the Canadian Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations provides a description of compatibility groups.

The United States Department of Transportation (DOT) regulates hazmat transportation within the territory of the US.

| |||||||||||

|

Mass Explosion Hazard |

Blast/Projection Hazard | |||||||||

Minor Blast Hazard |

Major Fire Hazard |

Blasting Agents | |||||||||

Extremely Insensitive Explosives |

|||||||||||

| Class 2: Gases | |||||||||||

Gases which are compressed, liquefied or dissolved under pressure as detailed below. Some gases have subsidiary risk classes; poisonous or corrosive.

| |||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Class 3: Flammable Liquids | |||||||||||

Flammable liquids included in Class 3 are included in one of the following packing groups:

Note: For further details, check the Dangerous Goods Transportation Regulations of the country of interest. | |||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Class 4: Flammable Solids | |||||||||||

4.1 Flammable Solids: Solid substances that are easily ignited and readily combustible (nitrocellulose, magnesium, safety or strike-anywhere matches). |

4.2 Spontaneously Combustible: Solid substances that ignite spontaneously (aluminium alkyls, white phosphorus). |

4.3 Dangerous when Wet: Solid substances that emit a flammable gas when wet or react violently with water (sodium, calcium, potassium, calcium carbide). | |||||||||

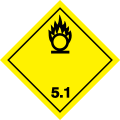

| Class 5: Oxidizing Agents and Organic Peroxides | |||||||||||

5.1 Oxidizing agents other than organic peroxides (calcium hypochlorite, ammonium nitrate, hydrogen peroxide, potassium permanganate). |

5.2 Organic peroxides, either in liquid or solid form (benzoyl peroxides, cumene hydroperoxide). |

||||||||||

| Class 6: Toxic and Infectious Substances | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Class 7: Radioactive Substances | Class 8: Corrosive Substances | Class 9: Miscellaneous | |||||||||

Radioactive substances comprise substances or a combination of substances which emit ionizing radiation (uranium, plutonium). |

Corrosive substances are substances that can dissolve organic tissue or severely corrode certain metals:

|

Hazardous substances that do not fall into the other categories (asbestos, air-bag inflators, self inflating life rafts, dry ice). | |||||||||

Handling and transportation

[edit]Handling

[edit]

Mitigating the risks associated with hazardous materials may require the application of safety precautions during their transport, use, storage and disposal. Most countries regulate hazardous materials by law, and they are subject to several international treaties as well. Even so, different countries may use different class diamonds for the same product. For example, in Australia, anhydrous ammonia UN 1005 is classified as 2.3 (toxic gas) with subsidiary hazard 8 (corrosive), whereas in the U.S. it is only classified as 2.2 (non-flammable gas).[6]

People who handle dangerous goods will often wear protective equipment, and metropolitan fire departments often have a response team specifically trained to deal with accidents and spills. Persons who may come into contact with dangerous goods as part of their work are also often subject to monitoring or health surveillance to ensure that their exposure does not exceed occupational exposure limits.

Laws and regulations on the use and handling of hazardous materials may differ depending on the activity and status of the material. For example, one set of requirements may apply to their use in the workplace while a different set of requirements may apply to spill response, sale for consumer use, or transportation. Most countries regulate some aspect of hazardous materials.

Packing groups

[edit]

Packing groups are used for the purpose of determining the degree of protective packaging required for dangerous goods during transportation.

- Group I: great danger, and most protective packaging required. Some combinations of different classes of dangerous goods on the same vehicle or in the same container are forbidden if one of the goods is Group I.[7]

- Group II: medium danger

- Group III: minor danger among regulated goods, and least protective packaging within the transportation requirement

Transport documents

[edit]One of the transport regulations is that, as an assistance during emergency situations, written instructions how to deal in such need to be carried and easily accessible in the driver's cabin.[8]

Dangerous goods shipments also require a dangerous goods transport document prepared by the shipper. The information that is generally required includes the shipper's name and address; the consignee's name and address; descriptions of each of the dangerous goods, along with their quantity, classification, and packaging; and emergency contact information. Common formats include the one issued by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) for air shipments and the form by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) for sea cargo.[9]

Training

[edit]A license or permit card for hazmat training must be presented when requested by officials.[10]

Society and culture

[edit]Global goals

[edit]The international community has defined the responsible management of hazardous waste and chemicals as an important part of sustainable development with Sustainable Development Goal 3. Target 3.9 has this target with respect to hazardous chemicals: "By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination."[11] Furthermore, Sustainable Development Goal 6 also mentions hazardous materials in Target 6.3: "By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials [...]."[12]

By country or region

[edit]Australia

[edit]The Australian Dangerous Goods Code[13] complies with international standards of importation and exportation of dangerous goods in line with the UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods. Australia uses the standard international UN numbers with a few slightly different signs on the back, front and sides of vehicles carrying hazardous substances. The country uses the same "Hazchem" code system as the UK to provide advisory information to emergency services personnel in the event of an emergency.

Canada

[edit]Transportation of dangerous goods (hazardous materials) in Canada by road is normally a provincial jurisdiction.[14] The federal government has jurisdiction over air, most marine, and most rail transport. The federal government acting centrally created the federal Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act and regulations, which provinces adopted in whole or in part via provincial transportation of dangerous goods legislation. The result is that all provinces use the federal regulations as their standard within their province; some small variances can exist because of provincial legislation. Creation of the federal regulations was coordinated by Transport Canada. Hazard classifications are based upon the UN model.

Outside of federal facilities, labour standards are generally under the jurisdiction of individual provinces and territories. However, communication about hazardous materials in the workplace has been standardized across the country through Health Canada's Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS).

Europe

[edit]The European Union has passed numerous directives and regulations to avoid the dissemination and restrict the usage of hazardous substances, important ones being the Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive (RoHS) and the REACH regulation. There are also long-standing European treaties such as ADR,[15] ADN and RID that regulate the transportation of hazardous materials by road, rail, river and inland waterways, following the guide of the UN model regulations.

European Union law distinguishes clearly between the law of dangerous goods and the law of hazardous materials.[citation needed] The first refers primarily to the transport of the respective goods including the interim storage, if caused by the transport. The latter describes the requirements of storage (including warehousing) and usage of hazardous materials. This distinction is important because different directives and orders of European law are applied.

United Kingdom

[edit]The United Kingdom (and also Australia, Malaysia, and New Zealand) use the Hazchem warning plate system which carries information on how an emergency service should deal with an incident. The Dangerous Goods Emergency Action Code List (EAC) lists dangerous goods; it is reviewed every two years and is an essential compliance document for all emergency services, local government and for those who may control the planning for, and prevention of, emergencies involving dangerous goods. The latest 2015 version is available from the National Chemical Emergency Centre (NCEC) website.[16] Guidance is available from the Health and Safety Executive.[17]

New Zealand

[edit]New Zealand's Land Transport Rule: Dangerous Goods 2005 and the Dangerous Goods Amendment 2010 describe the rules applied to the transportation of hazardous and dangerous goods in New Zealand. The system closely follows the United Nations Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods[18] and uses placards with Hazchem codes and UN numbers on packaging and the transporting vehicle's exterior to convey information to emergency services personnel.

Drivers that carry dangerous goods commercially, or carry quantities in excess of the rule's guidelines must obtain a D (dangerous goods) endorsement on their driver's licence. Drivers carrying quantities of goods under the rule's guidelines and for recreational or domestic purposes do not need any special endorsements.[19]

United States

[edit]

Due to the increase in fear of terrorism in the early 21st century after the September 11, 2001 attacks, funding for greater hazmat-handling capabilities was increased throughout the United States, recognizing that flammable, poisonous, explosive, or radioactive substances in particular could be used for terrorist attacks.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration regulates hazmat transportation within the territory of the US by Title 49 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulates the handling of hazardous materials in the workplace as well as response to hazardous-materials-related incidents, most notably through Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER).[20] regulations found at 29 CFR 1910.120.

In 1984 the agencies OSHA, EPA, USCG, and NIOSH jointly published the first Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response Guidance Manual[20] which is available for download.[21]

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates hazardous materials as they may impact the community and environment, including specific regulations for environmental cleanup and for handling and disposal of waste hazardous materials. For instance, transportation of hazardous materials is regulated by the Hazardous Materials Transportation Act. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act and analogous state laws were also passed to further protect human and environmental health.[22]

The Consumer Product Safety Commission regulates hazardous materials that may be used in products sold for household and other consumer uses.

Hazard classes for materials in transport

[edit]Following the UN model, the DOT divides regulated hazardous materials into nine classes, some of which are further subdivided. Hazardous materials in transportation must be placarded and have specified packaging and labelling. Some materials must always be placarded, others may only require placarding in certain circumstances.[23]

Trailers of goods in transport are usually marked with a four digit UN number. This number, along with standardized logs of hazmat information, can be referenced by first responders (firefighters, police officers, and ambulance personnel) who can find information about the material in the Emergency Response Guidebook.[24]

Fixed facilities

[edit]Different standards usually apply for handling and marking hazmats at fixed facilities, including NFPA 704 diamond markings (a consensus standard often adopted by local governmental jurisdictions), OSHA regulations requiring chemical safety information for employees, and CPSC requirements requiring informative labeling for the public, as well as wearing hazmat suits when handling hazardous materials.

See also

[edit]- ADR (treaty) – international arrangements for carriage of dangerous goods

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR)

- Area classification

- ASTM International – an international standards organization

- CLP Regulation

- Dangerous Goods Safety Advisor

- Directive 67/548/EEC

- Environmental hazard

- Hazardous materials apparatus

- UN number

- Hazchem

- Highly hazardous chemical

- List of Extremely Hazardous Substances

- List of UN Numbers

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standard 704 (US) (the "fire diamond")

- Packing group

- Pipe marking

- Poison control center

- Redundant refrigeration system

- Salvage drum

- Spill pallet

- Waste oil

References

[edit]- ^ "Resources Conservation and Recovery Act". US EPA. Archived from the original on June 26, 2013.

- ^ "Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR)". IATA. Archived from the original on 2014-04-23.

- ^ "2.0.2 UN numbers and proper shipping names". Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, Model Regulations. Vol. I (Twentyfirst ed.). United Nations. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "TDG Bulletin: Dangerous Goods Safety Marks" (PDF). Transport Canada. January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "Emergency Response Safety and Health Database". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Land Transport Rule - Dangerous Goods". New Zealand Land Transport Agency. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ "Guide for Preparing Shipping Papers" (PDF). US Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Chapter 5.4 Documentation". Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, Model Regulations. Vol. II (Twentyfirst ed.). United Nations. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "Hazmat transportation training requirements, An overview of 49 CFR parts 172-173" (PDF). U.S. Department of Transportation, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-17. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ^ Ritchie, Roser, Mispy, Ortiz-Ospina. "Measuring progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, Goal 3" SDG-Tracker.org, website (2018).

- ^ Australian Dangerous Goods Code National Transport Commission

- ^ Safety, Government of Canada, Transport Canada, Safety and Security, Motor Vehicle. "Information Links". www.tc.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2015-04-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "About the ADR". UNECE. Archived from the original on 2021-01-16. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ "The Dangerous Goods Emergency Action Code List 2017". the-ncec.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-17. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ^ "Carriage of Dangerous Goods - ADR and the carriage regulations 2004". www.hse.gov.uk. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- ^ "Rev. 12 (2001) - Transport - UNECE". www.unece.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-18.

- ^ "Transporting Hazardous or Dangerous Goods in a Truck or Car". 3 May 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-02-01.

- ^ a b "Hazardous waste operations and emergency response (HAZWOPER)". Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). 2006. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ DHHS (NIOSH) (October 1985), Occupational Safety and Health Guidance Manual for Hazardous Waste Site Activities, p. 142, Pub. no. 85-115, archived from the original on June 29, 2011, retrieved 2011-02-22

- ^ Taylor, Penny. "Transporting and Disposing of Dangerous Goods in the US: What You Need to Know". ACT Environmental Services. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Werman, Howard A.; Karren, K; Mistovich, Joseph (2014). "Protecting Yourself from Accidental and Work-Related Injury: Hazardous Materials". In Werman A. Howard; Mistovich J; Karren K (eds.). Prehospital Emergency Care, 10e. Pearson Education, Inc. p. 31.

- ^ Levins, Cory. "Dangerous Goods". Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

External links

[edit] Media related to Dangerous goods at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dangerous goods at Wikimedia Commons- Processing Radioactive Materials - large set of images by the IAEA showing automated package labelling and tracking for shipment of hazardous radioactive pharmaceuticals.

- Categorising Dangerous Materials - blog post explaining UN classification of dangerous materials.

- The 9 Classes of Dangerous Goods - blog post by Mintra explaining the 9 classes of dangerous goods

Dangerous goods

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

Dangerous goods, also referred to as hazardous materials in some jurisdictions, are defined as articles or substances capable of posing risks to human health, safety, property, or the environment due to their chemical, physical, or biological properties during transportation, handling, or storage incidental to transport.[7][2] These risks arise from potential hazards such as explosiveness, flammability, toxicity, corrosivity, reactivity, or environmental harm, which could lead to fires, explosions, spills, or exposures if not properly managed.[8] The definition is operationalized through classification systems that identify specific materials based on empirical testing of their properties, rather than subjective assessments, ensuring consistency across global supply chains.[9] The scope of dangerous goods regulations primarily encompasses all phases of transportation, including preparation, packaging, labeling, documentation, loading, unloading, and emergency response, across modes such as road, rail, inland waterways, sea, and air.[10][11] This broad application stems from the need to mitigate real-world incidents, such as chemical spills or aircraft fires, which have historically demonstrated the causal links between inadequate handling and severe consequences like fatalities or ecological damage.[12] Regulations extend to incidental storage during transit but exclude fixed-site manufacturing or long-term warehousing unless tied to transport activities.[13] Internationally harmonized under the United Nations Model Regulations (latest revision 23 adopted in 2023), the framework influences over 100 countries' laws, promoting standardized practices to reduce accident rates, which data shows have declined with compliance.[14][9] Exclusions within the scope typically cover small consumer quantities, certain radioactive materials under specialized regimes, or non-commercial personal effects deemed low-risk after evaluation, reflecting a risk-based approach grounded in quantitative hazard assessments rather than blanket prohibitions.[15] Domestic variations may adjust thresholds, such as the U.S. Department of Transportation's exemptions for limited quantities under 49 CFR, but core principles prioritize evidence of negligible risk.[13] Overall, the regulations target materials listed in nine hazard classes, from explosives (Class 1) to miscellaneous substances (Class 9), ensuring comprehensive coverage without overreach into non-transport contexts.[16]Historical Development

The regulation of dangerous goods originated in the 19th century amid the industrial revolution's expansion of rail and maritime transport, which increased accidents involving explosives, flammables, and chemicals. In the United States, the first federal law addressing hazardous materials transport was passed on July 28, 1866, prohibiting the shipment of nitroglycerin by common carriers after a series of deadly explosions, such as the 1866 Indianapolis disaster that killed 50 people; this evolved to cover explosives and flammable liquids more broadly by rail and vessel.[17] Similar national measures emerged elsewhere, driven by causal risks like spontaneous combustion and leaks, with railroads self-organizing through bodies like the 1907 Bureau of Explosives to standardize handling of high-risk cargoes.[18] International coordination began in the early 20th century, prompted by cross-border trade's amplification of hazards. At the 1912 Eighth International Congress of Applied Chemistry, Dr. Julius Abby advocated for unified global rules on chemical transport to mitigate inconsistent national standards. The 1929 International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) formally acknowledged the necessity of sea transport regulations for dangerous goods, following maritime incidents that underscored segregation and documentation needs. By 1948, the SOLAS conference established preliminary hazard classifications—such as explosives, gases, and corrosives—and general provisions for packaging and stowage, laying groundwork for multimodal applicability.[19] Post-World War II, the United Nations formalized harmonization through its Economic and Social Council, creating the Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods in 1957; their inaugural Recommendations, published that year (with roots in 1956 drafts), introduced a systematic framework of nine hazard classes, UN numbers, and packing requirements, applicable across road, rail, sea, and air while remaining non-binding models for national adoption. These evolved via biennial revisions, influencing modal codes like the 1965 International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code and the 1957 European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR). Subsequent updates, such as IMDG's mandatory enforcement under SOLAS in 2004, reflected empirical lessons from accidents like the 1987 Sandoz spill, prioritizing evidence-based risk mitigation over fragmented rules.[9][20]Classification and Identification

Hazard Classes

The hazard classes for dangerous goods are established by the United Nations Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, Model Regulations (latest revision 23, adopted December 2022), which categorize substances, materials, and articles based on their potential to cause harm through physical, chemical, health, or environmental effects during transport.[14] These classes, numbering nine in total, derive from empirical test criteria outlined in the UN Manual of Tests and Criteria, prioritizing the dominant hazard while allowing for subsidiary risks.[9] Classification ensures consistent global application across transport modes, with divisions and packing groups further refining risk levels based on sensitivity, toxicity, or reactivity data.[4]| Class | Divisions | Primary Hazard Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.1–1.6 | Explosives with detonation or projection risks |

| 2 | 2.1–2.3 | Gases under pressure (flammable, non-flammable, toxic) |

| 3 | None | Flammable liquids (flash point ≤60°C) |

| 4 | 4.1–4.3 | Flammable solids, self-reactive, or water-reactive substances |

| 5 | 5.1–5.2 | Oxidizers and organic peroxides enhancing combustion |

| 6 | 6.1–6.2 | Toxic or infectious substances |

| 7 | None | Radioactive materials |

| 8 | None | Corrosives to metals or skin |

| 9 | None | Miscellaneous (e.g., environmentally hazardous, lithium batteries) |

UN Numbers and Proper Shipping Names

UN numbers are four-digit identifiers, ranging from UN 0004 to UN 3535, assigned by the United Nations Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods to standardize the identification of hazardous substances and articles for international transport across all modes.[22] These numbers are specified in the UN Model Regulations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, which form the basis for national and international regulations, ensuring consistent hazard communication regardless of regional variations.[23] Assignment occurs through evaluation of a substance's properties against defined criteria for hazard classes, such as flammability or toxicity, with numbers allocated sequentially as new entries are approved by the committee during biennial revisions. Proper shipping names (PSNs) are the standardized technical descriptions listed in the UN Dangerous Goods List (in Part 3 of the Model Regulations), appearing in bold uppercase letters to precisely denote the material's composition and primary hazards, such as "ACETONE" (UN 1090) or "HYDROGEN PEROXIDE, AQUEOUS SOLUTION" (UN 2014).[24] Shippers must select the most specific PSN matching the goods; generic entries like "FLAMMABLE LIQUID, N.O.S." (UN 1993) require addition of technical names for mixtures or unlisted substances to ensure accurate risk assessment.[25] PSNs, combined with UN numbers, hazard classes, and packing groups, form the core of shipping descriptions on documents, packages, and vehicles, enabling emergency responders and regulators to identify risks without ambiguity.[26] The interplay between UN numbers and PSNs ensures traceability: each list entry pairs a unique number with one or more PSNs, sometimes with qualifiers like concentration limits (e.g., "with more than 30% hydrogen peroxide"), and special provisions for exemptions or additional requirements.[27] North American regulations use NA numbers (e.g., NA1993) for domestic substances not harmonized internationally, but UN numbers predominate in global shipments to align with treaties like the IMDG Code for sea or ICAO Technical Instructions for air.[26] Updates to the list, such as the 21st revised edition effective from January 1, 2023, reflect empirical testing and incident data to refine assignments, prioritizing causal factors like reactivity over outdated classifications.[22]Packing Groups and Labeling

Packing groups in the UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods classify substances and articles based on the degree of danger they pose during carriage, guiding the selection of appropriate packaging performance levels.[4] Substances are assigned to Packing Group I (high danger), Packing Group II (medium danger), or Packing Group III (low danger), though not all hazard classes use packing groups; for instance, gases (Class 2), explosives (Class 1), and radioactive materials (Class 7) typically lack this designation.[4][28] Assignment criteria are class-specific and rely on empirical tests or properties, such as for Class 8 corrosive substances where Packing Group I applies to materials causing full thickness destruction of human skin in under 60 minutes exposure, escalating to Packing Group III for effects after 60 minutes but under 4 hours.[29] For Class 3 flammable liquids, Packing Group I covers those with closed-cup flash points below 23°C and boiling points above 35°C, while Packing Group III includes liquids with flash points between 23°C and 60°C regardless of boiling point.[30] These groups determine packaging robustness under the UN Model Regulations: Packing Group I demands the highest drop, stack, and hydrostatic pressure test standards to withstand severe transport conditions, whereas Group III permits less stringent criteria suitable for lower-risk goods.[28] UN-certified packagings, including drums, boxes, and intermediate bulk containers, are marked with a UN specification code followed by capability indicators—X for Packing Group I (and II), Y for II (and III), or Z for III only—ensuring compatibility between the goods' assigned group and the container's tested limits.[31] This marking, typically stamped durably on the packaging, also includes the country of approval and manufacturer's details, verifiable against UN performance standards updated as of the 21st revised edition in 2021.[32] Labeling for dangerous goods transport requires affixing self-adhesive or silk-screened diamond-shaped labels (100 mm x 100 mm for packages under 500 kg, larger for bulk) to at least two opposite sides, displaying the relevant hazard class pictogram in black on a background color specific to the class (e.g., red for flammables), the class numeral, and division symbol if applicable.[33] Subsidiary hazard labels, indicated by a slashed line through the primary label edge, must be added for secondary risks, with Packing Group I toxic substances (Class 6.1) often requiring an additional "Inhalation Hazard" label for zone A gases or PG I solids/liquids posing acute inhalation risks.[33] Labels exclude explicit packing group notation except where subsidiary hazards demand it, prioritizing hazard communication over packaging details; however, for air transport under IATA rules aligned with UN standards, elevated temperature labels may apply to Packing Group II/III self-reactive substances.[32] Durability requirements mandate labels withstand environmental stresses like moisture and abrasion, with text in the official language of the dispatching country plus English for international shipments.[33] Placards, scaled-up versions of labels (at least 250 mm square), are required on transport units like trucks or freight containers for quantities exceeding thresholds, such as 1,000 kg for Packing Group III solids in road transport.[34]Regulatory Frameworks

International Standards

The United Nations Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, commonly referred to as the UN Model Regulations, establish the foundational international framework for classifying, packaging, labeling, and documenting hazardous materials during transport by road, rail, air, and sea, excluding bulk carriers. Developed by the UN Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods and managed through the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), these non-binding recommendations promote global harmonization to minimize risks of accidents, environmental damage, and public harm. The regulations define nine hazard classes based on intrinsic properties such as flammability, toxicity, and reactivity, assign unique UN numbers to over 3,000 substances, and specify packing groups (I, II, III) reflecting degrees of danger.[14][9] The 23rd revised edition, published in 2023, incorporates amendments adopted on December 9, 2022, including updates to provisions for electric storage systems, portable tanks, and certain chemical listings to address emerging risks from technological advancements. Biennial revisions ensure alignment with scientific data on material hazards and incident analyses, with testing criteria outlined in a companion Manual of Tests and Criteria for verifying classifications empirically. While not enforceable directly, over 100 countries incorporate the Model Regulations into national laws, facilitating cross-border trade; deviations occur where local conditions, such as infrastructure limitations, necessitate adaptations, though these must maintain equivalent safety levels.[14][35] International modal bodies adapt the UN Model for specific transport environments. The International Maritime Organization's (IMO) International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code governs sea transport of packaged goods, mandating compliance under the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) and MARPOL conventions to prevent marine pollution and crew exposure; Amendment 42-24, effective January 1, 2026 (voluntary from January 1, 2025), refines segregation rules and stowage provisions based on vessel stability data and historical spill incidents. For air transport, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Technical Instructions form the basis, implemented via the International Air Transport Association's (IATA) Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR), with the 66th edition effective January 1, 2025, introducing expanded entries for sodium-ion batteries and revised packing instructions derived from crash test simulations and fire suppression efficacy studies. Inland waterway (ADN) and rail (RID, COTIF Appendix C) regulations similarly derive from the UN Model, ensuring interoperability in multimodal shipments.[36][37][15] These standards emphasize performance-based criteria over prescriptive rules, allowing flexibility while requiring verifiable testing for packaging integrity under drop, stack, and vibration conditions to reflect real-world causal factors like impact forces and thermal runaway. Compliance training and competent authority oversight, as per UN guidelines, reduce error rates, with data from global incident reports informing iterative improvements; for instance, post-2010 lithium battery fire analyses prompted stricter state-of-charge limits in air shipments.[38][39]Regional and National Variations

In the United States, hazardous materials transportation is regulated under Title 49 of the Code of Federal Regulations (49 CFR), administered by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) within the Department of Transportation (DOT). While 49 CFR is substantially harmonized with the UN Model Regulations to facilitate international commerce, notable differences persist, including unique U.S. designations such as "hazardous substances" that impose additional reporting and spill response requirements not found in the UN framework.[40][41] For air transport, U.S. variations to ICAO Technical Instructions require prior approval for certain items like specific explosives or require compliance with either 49 CFR or the Technical Instructions, with restrictions on substances such as certain desensitized explosives.[40] These deviations can complicate multimodal shipments crossing borders.[42] The European Union implements UN recommendations through Directive 2008/68/EC, which coordinates inland transport regulations including the European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR), by Rail (RID), and by Inland Waterway (ADN). These are closely aligned with the UN Model Regulations, with updates such as ADR 2025 incorporating amendments for new entries like sodium-ion batteries and revised packaging for hazardous waste, but introducing EU-specific provisions for vehicle construction and tank approvals to enhance regional safety.[2][43][44] Post-Brexit, the United Kingdom retains ADR alignment but has introduced national variations, such as updated state provisions in IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations for lithium batteries.[45] Australia's Dangerous Goods Code (ADG) for road and rail transport adopts the structure, classifications, and packaging standards of the UN Model Regulations (21st revised edition as of its latest alignment), ensuring compatibility for exports, but includes national supplements like additional guidance on manifest quantities and state-level enforcement variations.[46][47] For instance, the ADG mandates enhanced classification details for certain chemicals not explicitly required in the UN text, reflecting local environmental and infrastructure considerations.[48] Other nations exhibit similar patterns of adaptation; Canada's Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (TDG) mirror U.S. 49 CFR for cross-border harmony but add provisions for bilingual documentation. Globally, air transport sees extensive state variations—over 1,200 documented in the IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations—affecting prohibitions on specific goods like certain radioactive materials in countries such as Chile or the UAE.[49] These national overlays address jurisdiction-specific risks, such as population density or climate, while striving for interoperability under UN baselines.[50]Operational Handling and Transport

Packaging and Segregation

Packaging for dangerous goods must conform to performance-based standards outlined in the United Nations Model Regulations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, which specify requirements for containment, durability, and resistance to transport stresses such as drops, vibrations, and pressure changes.[14] These standards mandate the use of UN-approved packaging, marked with a four-digit code indicating the type, material, and test criteria, ensuring packages can withstand specific hazards like leakage or explosion risks without failure.[51] For instance, inner packagings hold the goods directly, while outer packagings provide additional protection; both must be compatible with the substance's chemical properties and assigned to Packing Groups I (great danger, e.g., requiring stringent drop and stack tests), II (medium danger), or III (low danger) based on empirical criteria like liquid flash point or solid ignition temperature.[23] Reusable packaging requires re-testing every five years or after repairs, with documentation verifying compliance to mitigate risks of containment breach during multimodal transport.[52] In the United States, the Department of Transportation's Hazardous Materials Regulations (49 CFR Parts 173 and 178) align closely with UN standards but include additional specifications for non-bulk packagings, such as maximum capacities (e.g., 30 liters for most Packing Group I liquids in metal drums) and compatibility prohibitions against mixing hazardous materials that could react adversely within the same package.[53] For air transport, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) Dangerous Goods Regulations detail packing instructions (e.g., PI 650 for solids) that limit quantities, require cushioning materials, and prohibit overpacking incompatible substances, with exemptions for small quantities under excepted provisions to balance safety and efficiency.[15] These measures stem from causal analyses of past incidents, where inadequate packaging contributed to 15-20% of hazmat releases in U.S. ground transport from 2010-2020, underscoring the need for rigorous testing like the UN's 1.2-meter drop test for Packing Group II solids.[13] Segregation rules prevent dangerous interactions between incompatible goods, such as acids with bases or flammables with oxidizers, by enforcing spatial separation during stowage and transport, as codified in modal regulations harmonized with UN recommendations.[14] The International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code, in Chapter 7.2, uses a matrix-based table for 18 segregation groups (e.g., acids segregated from alkalis via "away from" provisions allowing same-compartment storage if non-reactive) and specifies four levels: "away from" (no direct contact), "separated from" (different holds or bays), "separated by complete compartment," or "separated longitudinally" for high-risk pairs like Class 1 explosives and Class 5.1 oxidizers.[36] For example, under IMDG, Class 3 flammable liquids must be segregated from Class 5.1 oxidizers to avoid ignition propagation, with empirical data from maritime incidents showing non-compliance doubles reaction risks.[54] In air transport, IATA's Table 9.3A employs an "X" notation for incompatibilities, prohibiting mixed loading of certain classes (e.g., no Class 2.3 toxic gases with Class 4.2 spontaneous combustibles in the same unit load device), while U.S. 49 CFR §176.83 mandates separate cargo transport units for any required segregation, extending to vessel holds or aircraft compartments.[15][55] These protocols, updated biennially (e.g., IMDG Amendment 41-22 effective 2022), reflect first-principles risk assessment prioritizing physical separation to interrupt causal chains of secondary hazards, with violations linked to over 10% of reported global hazmat incidents per International Maritime Organization data from 2015-2020.[36]| Segregation Level | Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Away from | Goods may be in same compartment if no interaction risk | Class 6.1 poisons away from Class 8 corrosives unless segregated group compatible[56] |

| Separated from | Different holds/bays or 3m separation | Flammables (Class 3) from oxidizers (Class 5.1) |

| Complete compartment | Full barrier required | Explosives (Class 1) from toxic gases (Class 2.3)[36] |

| Longitudinally separated | 6m along vessel length | Spontaneous combustibles (Class 4.2) from water-reactives (Class 4.3)[57] |

Modes of Transportation

The transportation of dangerous goods occurs primarily by road, rail, air, and sea, with each mode subject to mode-specific regulations harmonized with the United Nations Model Regulations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods to address unique hazards such as vibration, temperature extremes, and potential for mass releases.[58] These frameworks mandate packaging integrity, labeling, segregation, and emergency response protocols tailored to the transport environment, with road and rail handling bulk volumes of flammable liquids and gases, while air and sea prioritize restricted quantities due to higher consequence risks.[59] Road transport, the most common mode for dangerous goods in terms of shipment volume, is regulated internationally by the European Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR), established in 1957 and updated biennially; the 2025 edition entered force on January 1, 2025, with a six-month transition period.[60] In the United States, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) enforces requirements under 49 CFR Parts 170-177, including vehicle placarding, driver certification, and route restrictions to mitigate spill risks from collisions, which account for approximately 93% of hazmat incidents nationwide.[13] [61] Key measures include tank truck specifications for pressure resistance and real-time monitoring, though empirical data indicate higher per-shipment accident rates compared to rail due to traffic density and human error.[62] Rail transport facilitates large-scale movement of hazardous materials like chemicals and explosives over long distances, governed by the Regulations concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Rail (RID), Appendix C to the Convention concerning International Carriage by Rail (COTIF), with the 2025 edition effective from January 1, 2025.[63] In the U.S., the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) and Federal Railroad Administration oversee compliance via 49 CFR Parts 171-174, emphasizing tank car designs with pressure relief valves and trackside detection systems.[64] Freight rail demonstrates superior safety, with over 99.99% of hazmat shipments arriving without accidental release, attributed to dedicated tracks and lower exposure to public areas, though derailments can result in concentrated releases affecting waterways.[65] Air transport imposes the strictest controls due to the confined cabin environment and crash dynamics, relying on the International Air Transport Association (IATA) Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR), updated annually and aligned with ICAO Technical Instructions; the 2025 edition incorporates lithium battery restrictions and enhanced documentation.[15] Certain substances, such as certain explosives or infectious agents, are prohibited or limited to small quantities, with mandatory shipper declarations and operator acceptance checks under 14 CFR in the U.S., reducing risks of in-flight reactions but elevating costs through specialized handling.[12] Incidents remain rare, but potential for widespread dispersal in crashes underscores the mode's emphasis on pre-flight verification over volume throughput.[39] Maritime transport, critical for global bulk shipments of petroleum and chemicals, follows the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code administered by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), mandatory under the SOLAS Convention; the 2024 edition (Amendment 42-24) applies voluntarily from January 1, 2025, and mandatorily from January 1, 2026. Provisions cover stowage segregation to prevent reactions, container ventilation, and pollution prevention via double-hull requirements, protecting against marine ecosystems from spills—evident in reduced incident severity post-IMO implementation, though container ship fires highlight ongoing challenges with misdeclared cargoes.[66] Intermodal shipments often combine modes, necessitating compatibility checks under overarching frameworks like the U.S. Hazardous Materials Regulations to ensure unbroken compliance chains.[67]Documentation and Training Requirements

Documentation for the transport of dangerous goods consists of shipping papers that identify the substances, their hazards, quantities, and emergency response procedures, enabling carriers, emergency responders, and regulators to manage risks effectively. These documents must accompany shipments and include details such as UN numbers, proper shipping names, hazard classes, packing groups, and special provisions derived from the UN Model Regulations.[22] Internationally, Chapter 5.4 of the UN Recommendations outlines standardized documentation requirements, including the Dangerous Goods Declaration, which certifies compliance with classification, packaging, marking, and labeling standards.[68] For maritime transport, the IMDG Code mandates a Dangerous Goods Manifest or Stowage Plan detailing cargo locations and compatibility, while air shipments under IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations require a Shipper's Declaration for Dangerous Goods alongside the Air Waybill. The IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR) do not require Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) or Safety Data Sheets (SDS) as transport documents for shipping dangerous goods by air; they are not mandatory for transport purposes or for articles (e.g., lithium batteries). MSDS/SDS may assist in classification but are often inaccurate for transport purposes; shippers should verify with manufacturers or testing. Specific operator variations may require them, such as SDS/MSDS for most dangerous goods with Malaysia Airlines (MH-13, with exceptions).[69][15][39] For road and rail transport under ADR or DOT regulations similarly demands transport documents with consignor and consignee details, net quantity, and emergency contact information, updated to reflect biennial revisions in UN standards.[60][70] Training requirements apply to all personnel involved in the preparation, handling, loading, unloading, or emergency response for dangerous goods shipments, ensuring competency in hazard recognition and regulatory compliance. The UN Recommendations emphasize training on classification, packaging, documentation, and incident response, serving as the foundation for modal-specific programs.[71] Under IATA and ICAO Technical Instructions, training is competency-based, covering general awareness, function-specific tasks, and safety measures, with recurrent training required every 24 months and certification documented for auditing.[72][73] IMDG Code provisions extend training to shoreside workers, focusing on maritime-specific segregation and stowage, while DOT regulations (49 CFR 172.704) mandate general awareness, function-specific, and safety training for hazmat employees, refreshed every three years with testing to verify proficiency.[74][75] Non-compliance, such as operating without valid training certificates, can result in shipment refusals or penalties, as enforced by carriers adhering to these harmonized standards.[39]Risks, Incidents, and Mitigation

Statistical Overview of Incidents

In the United States, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) records approximately 24,000 to 25,000 hazardous materials incidents annually across all transport modes, with 24,265 reported in 2023, reflecting a 3.6% decline from 2022 levels.[76] Highway transport accounts for the majority, comprising over 90% of incidents due to the volume of road shipments, while rail, air, and water modes contribute smaller shares, with rail incidents often involving larger releases but fewer occurrences.[67] Fatalities remain low relative to incident volume, totaling 9 deaths and 631 injuries in a recent reporting period, underscoring that most events involve minor releases or packaging failures rather than catastrophic failures.[77]| Year | Total Incidents | Fatalities | Injuries | Property Damage (millions USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | ~25,000 | Low single digits | ~600 | Varied, often under 100 |

| 2022 | ~25,175 | 9 | 631 | Not specified in aggregate |

| 2023 | 24,265 | Low single digits | ~600 | Not specified in aggregate |