Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hexose

View on WikipediaIn chemistry, a hexose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with six carbon atoms.[1][2] The chemical formula for all hexoses is C6H12O6, and their molecular weight is 180.156 g/mol.[3]

Hexoses exist in two forms, open-chain or cyclic, that easily convert into each other in aqueous solutions.[4] The open-chain form of a hexose, which usually is favored in solutions, has the general structure H−(CHOH)n−1−C(=O)−(CHOH)6−n−H, where n is 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Namely, five of the carbons have one hydroxyl functional group (−OH) each, connected by a single bond, and one has an oxo group (=O), forming a carbonyl group (C=O). The remaining bonds of the carbon atoms are satisfied by seven hydrogen atoms. The carbons are commonly numbered 1 to 6 starting at the end closest to the carbonyl.

Hexoses are extremely important in biochemistry, both as isolated molecules (such as glucose and fructose) and as building blocks of other compounds such as starch, cellulose, and glycosides. Hexoses can form dihexose (like sucrose) by a condensation reaction that makes 1,6-glycosidic bond.

When the carbonyl is in position 1, forming a formyl group (−CH=O), the sugar is called an aldohexose, a special case of aldose. Otherwise, if the carbonyl position is 2 or 3, the sugar is a derivative of a ketone, and is called a ketohexose, a special case of ketose; specifically, an n-ketohexose.[1][2] However, the 3-ketohexoses have not been observed in nature, and are difficult to synthesize;[5] so the term "ketohexose" usually means 2-ketohexose.

In the linear form, there are 16 aldohexoses and eight 2-ketohexoses, stereoisomers that differ in the spatial position of the hydroxyl groups. These species occur in pairs of optical isomers. Each pair has a conventional name (like "glucose" or "fructose"), and the two members are labeled "D-" or "L-", depending on whether the hydroxyl in position 5, in the Fischer projection of the molecule, is to the right or to the left of the axis, respectively. These labels are independent of the optical activity of the isomers. In general, only one of the two enantiomers occurs naturally (for example, D-glucose) and can be metabolized by animals or fermented by yeasts.

The term "hexose" sometimes is assumed to include deoxyhexoses, such as fucose and rhamnose: compounds with general formula C6H12O6−y that can be described as derived from hexoses by replacement of one or more hydroxyl groups with hydrogen atoms.

Classification

[edit]Aldohexoses

[edit]The aldohexoses are a subclass of the hexoses which, in the linear form, have the carbonyl at carbon 1, forming an aldehyde derivative with structure H−C(=O)−(CHOH)5−H.[1][2] The most important example is glucose.

In linear form, an aldohexose has four chiral centres, which give 16 possible aldohexose stereoisomers (24), comprising 8 pairs of enantiomers. The linear forms of the eight D-aldohexoses, in the Fischer projection, are

Of these D-isomers, all except D-altrose occur in living organisms, but only three are common: D-glucose, D-galactose, and D-mannose. The L-isomers are generally absent in living organisms; however, L-altrose has been isolated from strains of the bacterium Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens.[6]

When drawn in this order, the Fischer projections of the D-aldohexoses can be identified with the 3-digit binary numbers from 0 to 7, namely 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, 111. The three bits, from left to right, indicate the position of the hydroxyls on carbons 4, 3, and 2, respectively: to the right if the bit value is 0, and to the left if the value is 1.

The chemist Emil Fischer is said[citation needed] to have devised the following mnemonic device for remembering the order given above, which corresponds to the configurations about the chiral centers when ordered as 3-bit binary strings:

- All altruists gladly make gum in gallon tanks.

referring to allose, altrose, glucose, mannose, gulose, idose, galactose, talose.

The Fischer diagrams of the eight L-aldohexoses are the mirror images of the corresponding D-isomers; with all hydroxyls reversed, including the one on carbon 5.

Ketohexoses

[edit]A ketohexose is a ketone-containing hexose.[1][2][7] The important ketohexoses are the 2-ketohexoses, and the most important 2-ketose is fructose.

Besides the 2-ketoses, there are only the 3-Ketoses, and they do not exist in nature, although at least one 3-ketohexose has been synthesized, with great difficulty.

In the linear form, the 2-ketohexoses have three chiral centers and therefore eight possible stereoisomers (23), comprising four pairs of enantiomers. The four D-isomers are:

The corresponding L forms have the hydroxyls on carbons 3, 4, and 5 reversed. Below are depiction of the eight isomers in an alternative style:

3-Ketohexoses

[edit]In theory, the ketohexoses include also the 3-ketohexoses, which have the carbonyl in position 3; namely H−(CHOH)2−C(=O)−(CHOH)3−H. However, these compounds are not known to occur in nature, and are difficult to synthesize.[5]

In 1897, an unfermentable product obtained by treatment of fructose with bases, in particular lead(II) hydroxide, was given the name glutose, a portmanteau of glucose and fructose, and was claimed to be a 3-ketohexose.[12][13] However, subsequent studies showed that the substance was a mixture of various other compounds.[13][14]

The unequivocal synthesis and isolation of a 3-ketohexose, xylo-3-hexulose, through a rather complex route, was first reported in 1961 by George U. Yuen and James M. Sugihara.[5]

Cyclic forms

[edit]Like most monosaccharides with five or more carbons, each aldohexose or 2-ketohexose also exists in one or more cyclic (closed-chain) forms, derived from the open-chain form by an internal rearrangement between the carbonyl group and one of the hydroxyl groups.

The reaction turns the =O group into a hydroxyl, and the hydroxyl into an ether bridge (−O−) between the two carbon atoms, thus creating a ring with one oxygen atom and four or five carbons.

If the cycle has five carbon atoms (six atoms in total), the closed form is called a pyranose, after the cyclic ether tetrahydropyran, that has the same ring. If the cycle has four carbon atoms (five in total), the form is called furanose after the compound tetrahydrofuran.[4] The conventional numbering of the carbons in the closed form is the same as in the open-chain form.

If the sugar is an aldohexose, with the carbonyl in position 1, the reaction may involve the hydroxyl on carbon 4 or carbon 5, creating a hemiacetal with five- or six-membered ring, respectively. If the sugar is a 2-ketohexose, it can only involve the hydroxyl in carbon 5, and will create a hemiketal with a five-membered ring.

The closure turns the carboxyl carbon into a chiral center, which may have either of two configurations, depending on the position of the new hydroxyl. Therefore, each hexose in linear form can produce two distinct closed forms, identified by prefixes "α" and "β".

It has been known since 1926 that hexoses in the crystalline solid state assume the cyclic form. The "α" and "β" forms, which are not enantiomers, will usually crystallize separately as distinct species. For example, D-glucose forms an α crystal that has specific rotation of +112° and melting point of 146 °C, as well as a β crystal that has specific rotation of +19° and melting point of 150 °C.[4]

The linear form does not crystallize, and exists only in small amounts in water solutions, where it is in equilibrium with the closed forms.[4] Nevertheless, it plays an essential role as the intermediate stage between those closed forms.

In particular, the "α" and "β" forms can convert to into each other by returning to the open-chain form and then closing in the opposite configuration. This process is called mutarotation.

Chemical properties

[edit]Although all hexoses have similar structures and share some general properties, each enantiomer pair has its own chemistry. Fructose is soluble in water, alcohol, and ether.[9] The two enantiomers of each pair generally have vastly different biological properties.

2-Ketohexoses are stable over a wide pH range, and with a primary pKa of 10.28, will only deprotonate at high pH, so are marginally less stable than aldohexoses in solution.

Natural occurrence and uses

[edit]The aldohexose that is most important in biochemistry is D-glucose, which is the main "fuel" for metabolism in many living organisms.

The 2-ketohexoses psicose, fructose and tagatose occur naturally as the D-isomers, whereas sorbose occurs naturally as the L-isomer.

D-Sorbose is commonly used in the commercial synthesis of ascorbic acid.[10] D-Tagatose is a rare natural ketohexose that is found in small quantities in food.[11] D-Fructose is responsible for the sweet taste of many fruits, and is a building block of sucrose, the common sugar.

Deoxyhexoses

[edit]The term "hexose" may sometimes be used to include the deoxyhexoses, which have one or more hydroxyls (−OH) replaced by hydrogen atoms (−H). It is named as the parent hexose, with the prefix "x-deoxy-", the x indicating the carbon with the affected hydroxyl. Some examples of biological interest are

- L-Fucose (6-deoxy-L-galactose)

- L-Rhamnose (6-deoxy-L-mannose)

- D-Quinovose (6-deoxy-D-glucose), found as part of the sulfolipid sulfoquinovosyl diacylglycerol (SQDG)

- L-Pneumose (6-deoxy-L-talose)

- L-Fuculose (6-deoxy-L-tagatose)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Thisbe K. Lindhorst (2007). Essentials of Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry (1 ed.). Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-31528-4.

- ^ a b c d John F. Robyt (1997). Essentials of Carbohydrate Chemistry (1 ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-387-94951-8.

- ^ Pubchem. "D-Psicose". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ^ a b c d Robert Thornton Morrison and Robert Neilson Boyd (1998): Organic Chemistry, 6th edition. ISBN 9780138924645

- ^ a b c George U. Yuen and James M. Sugihara (1961): "". Journal of Organic Chemistry, volume 26, issue 5, pages 1598-1601. doi:10.1021/jo01064a070

- ^ US patent 4966845, Stack; Robert J., "Microbial production of L-altrose", issued 1990-10-30, assigned to Government of the United States of America, Secretary of Agriculture

- ^ Milton Orchin, ed. (1980). The vocabulary of organic chemistry. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-04491-8.

- ^ Pubchem. "D-Psicose". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ^ a b Pubchem. "Fructose". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ^ a b Pubchem. "Sorbose, D-". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ^ a b Pubchem. "Tagatose". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ^ C. A. Lobry de Bruyn and W. Alberda van Ekenstein (1897): "Action des alcalis sur les sucres. VI: La glutose et la pseudo‐fructose". Recueil des Travaux Chimiques des Pays-Bas et de la Belgique, volume 16, issue 9, pages 274-281. doi:10.1002/recl.18970160903

- ^ a b George L. Clark, Hung Kao, Louis Sattler, and F. W. Zerban (1949): "Chemical Nature of Glutose". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry, volume 41, issue 3, pages 530-533. doi:10.1021/ie50471a020

- ^ Akira Sera (1962): "Studies on the Chemical Decomposition of Simple Sugars. XIII. Separation of the So-called Glutose (a 3-Ketohexose)". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, volume 35, issue 12, pages 2031-2033. doi:10.1246/bcsj.35.2031

External links

[edit] Media related to Aldohexoses at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aldohexoses at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Ketohexoses at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ketohexoses at Wikimedia Commons

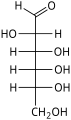

![D-Psicose[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/DPsicose_Fischer.svg/62px-DPsicose_Fischer.svg.png)

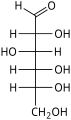

![D-Fructose[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e5/D-Fructose.svg/120px-D-Fructose.svg.png)

![D-Sorbose[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/DSorbose_Fischer.svg/70px-DSorbose_Fischer.svg.png)

![D-Tagatose[11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/DTagatose_Fischer.svg/70px-DTagatose_Fischer.svg.png)