Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

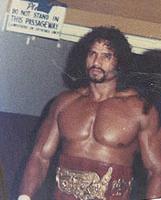

Jimmy Snuka

View on Wikipedia

James Reiher Snuka[a] (born James Wiley Smith; May 18, 1943 – January 15, 2017) was a Fijian and American professional wrestler, better known by the ring name Jimmy "Superfly" Snuka.

Key Information

Snuka wrestled for several promotions from the 1970s to 2010s. He was best known for his time in the World Wrestling Federation (WWF, now WWE) in the 1980s to where he was credited with introducing the high-flying wrestling style.[1] He was inducted into the WWF Hall of Fame in 1996, and was the inaugural ECW World Heavyweight Champion (a title he held twice) in Eastern Championship Wrestling (later Extreme Championship Wrestling). His children, Sim Snuka and Tamina Snuka, are both professional wrestlers.

Snuka was indicted and arrested in September 2015 on third-degree murder and involuntary manslaughter charges in relation to the May 1983 death of his girlfriend and mistress, Nancy Argentino, in Allentown, Pennsylvania. He pleaded not guilty,[9][10] but was found unfit to stand trial in June 2016 due to dementia.[11] Terminally ill with stomach cancer,[12] his charges were dismissed on January 3, 2017, twelve days before his death.[13]

Early life

[edit]Snuka was born in the British colony of Fiji on May 18, 1943, to Louisa Smith and Charles Thomas.[14] Thomas was married to another woman, and Smith was engaged to Bernard Reiher. Before Snuka was born, his mother married Reiher.[15] As a child, Snuka moved with his family to the Marshall Islands and then to Hawaii.[16]

Snuka was active in amateur bodybuilding in Hawaii in the 1960s. He also enjoyed some success as a professional bodybuilder, earning the titles of Mr. Hawaii, Mr. Waikiki and Mr. North Shore.[17]

Professional wrestling career

[edit]Early career (1968–1981)

[edit]

Snuka opted to go into the more lucrative career of professional wrestling due to the uncertainty of his making a living in bodybuilding.[18] While working at Dean Ho's gym in Hawaii, Snuka met many of the wrestlers who worked in the South Pacific region and decided to try the business.[17] Snuka made his debut as Jimmy Kealoha fighting Maxwell "Bunny" Butler in Hawaii in 1970. He later moved to the mainland and wrestled for Don Owen’s NWA Pacific Northwest territory where he held the belt as heavyweight champion six times.[19] He first won the title by pinning Bull Ramos on November 16, 1973.[20] It was in this territory that Reiher transformed himself into Jimmy Snuka. Snuka also held the NWA Pacific Northwest Tag Team Championship six times with partner Dutch Savage. Snuka also had a two-year feud with another rookie, Jesse "the Body" Ventura.[17]

Snuka also wrestled in several other National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) regions, including Texas. In 1977, he won both the Texas heavyweight and tag team titles. Snuka then left for the Mid-Atlantic where he formed a tag team with Paul Orndorff. In their first television match they defeated the NWA World Tag Team champions Jack and Jerry Brisco in a non-title bout. Orndorff and Snuka defeated Baron von Raschke and Greg Valentine to become the tag team title holders in 1979. On September 1, 1979, Snuka defeated Ricky Steamboat to hold the United States title. Snuka also formed a tag team with Ray Stevens while with this promotion. His career eventually led him to Georgia, where he teamed with Terry Gordy to win the NWA National Tag Team Championship by defeating Ted DiBiase and Steve Olsonoski."[21]

World Wrestling Federation (1982–1985)

[edit]

In January 1982, Snuka entered the World Wrestling Federation (WWF) as a villainous character under the guidance of Captain Lou Albano. Snuka lost several title shots at WWF champion Bob Backlund, including a steel cage match at Madison Square Garden on June 28, 1982, in which Snuka leapt from the top of the cage and missed a prone Backlund, who managed to roll out of the way and escape the cage for the win.[22]: 369 The contest was declared Match of the Year by Pro Wrestling Illustrated.[22]: 369

Even though Snuka portrayed a violent villain, he won fans because of his athletic style.[17][23] In a storyline in 1982, Buddy Rogers told Snuka that Albano was cheating him financially, and as a result, Snuka fired Albano. Snuka took on Rogers as his manager during the feud with Albano, Freddie Blassie, and Ray Stevens. The attack solidified Snuka's new role as a fan favorite seeking to settle the score.[24] Snuka defeated Stevens in the majority of the series of matches between the two.[25] He also faced several other of Albano's wrestlers,[26] and defeated Albano in a steel cage match in Madison Square Garden.[26][27]

Snuka also feuded with Don Muraco in 1983, which began after Snuka entered the ring for a match against Don Kernodle on the June 18 episode of Championship Wrestling while Muraco, the Intercontinental Heavyweight champion, was being interviewed. Muraco, enraged at the perceived lack of respect, confronted Snuka at ringside, triggering a brawl.[28] This feud led to a defining moment of Snuka's career on October 17, 1983, in a steel cage match at Madison Square Garden. The match ended in a loss for Snuka, but afterward he dragged Muraco back into the ring and connected with the most famous "Superfly splash" of his career, off the top of the 15-foot (4.6 m) high steel cage.[29] Future wrestling stars the Sandman, Mick Foley, Tommy Dreamer, and Bubba Ray Dudley were all in attendance at the event and cite this match as the reason they decided to actively pursue professional wrestling.[29] Snuka was named the 1983 Wrestler of the Year by Victory Magazine (later renamed WWF Magazine)[30] for his efforts.[31]

In June 1984, Snuka became embroiled in a feud with one of the WWF's top villains, "Rowdy" Roddy Piper. In a segment of Piper's Pit, Piper hit Snuka on the left side of his head very close to the temple, with a coconut.[32][33] The attack led to a series of grudge matches between the two that were played out over venues across the US throughout the summer of 1984. In late 1984, Snuka entered a rehabilitation facility; the WWF created a storyline in which Piper had broken Snuka's neck by hitting him over the head with a chair.[2][34] Tonga Kid, who was billed as Snuka's cousin, continued the feud on Snuka's behalf.[34]

The remainder of Snuka's initial WWF stint had him frequently tangling with Piper one way or another, often via tag matches or wrestling Piper's closest ally, Bob Orton Jr. Snuka defeated Orton at The War to Settle the Score on February 18, 1985; an injury during the match forced Orton to wear a cast on his left arm,[35][36] which he continued to wear after the injury healed.[37] The feud played a small part in the first WrestleMania, in March 1985, when Snuka acted as a cornerman for Hulk Hogan and Mr. T when they defeated Piper and Paul Orndorff (with Orton in their corner).[38] Snuka left the WWF in July 1985,[3] though he still appeared in cartoon form when Hulk Hogan's Rock 'n' Wrestling premiered in September.[39][40]

Japan, AWA and more (1985–1988)

[edit]After spending the rest of 1985 and early 1986 competing for New Japan Pro-Wrestling,[3] Snuka resurfaced in the American Wrestling Association (AWA), replacing Jerry Blackwell as Greg Gagne's partner,[41] to defeat Bruiser Brody and Nord the Barbarian in a tag team cage match at WrestleRock 86.[42]

Snuka split his time between the AWA and Japan throughout 1986 and 1987.[43] His most notable feud in the AWA during that time was with Colonel DeBeers, who portrayed a racist and looked down on Snuka because of his skin color.[44] This led the way for a series of grudge matches in 1987.[43]

Snuka also worked for Pacific Northwest Wrestling and Continental Wrestling Association. In 1988, he worked a couple of matches in Singapore. He wrestled throughout 1988 for All Japan Pro Wrestling, often teaming with Tiger Mask.

Return to WWF (1989–1993)

[edit]

Snuka re-emerged in the WWF at WrestleMania V on April 2, 1989.[45][dubious – discuss] He made his televised return to action on the May 27 episode of Saturday Night's Main Event XXI, defeating Boris Zhukov.[22]: 762 After a brief feud with the Honky Tonk Man,[46] Snuka made his in-ring pay-per-view debut at SummerSlam against "Million Dollar Man" Ted DiBiase. Snuka lost the match by count-out as a result of interference from DiBiase's bodyguard Virgil.[46][47]

By the later part of 1989, Snuka was put into a spot like many veterans before him, being used to help put over other rising stars such as "Mr. Perfect" Curt Hennig. At the Survivor Series, Snuka and Hennig were each the final remaining members of their teams, with Hennig pinning Snuka to win the match for his team.[22]: 797 In January 1990, Snuka made his Royal Rumble match debut, lasting 17 minutes and eliminating two competitors before being eliminated by the eventual winner, Hulk Hogan. Snuka had his first WrestleMania match at WrestleMania VI, where he was defeated by Rick Rude.[48] When the Intercontinental Championship was vacated after WrestleMania, Snuka entered the tournament to crown a new champion. He was eliminated in the first round when he once again lost to Mr. Perfect.[49] At that November's Survivor Series, Snuka joined Jake Roberts and the Rockers in a losing effort against Rick Martel, the Warlord and Power and Glory.[50]

On March 24, 1991, Snuka was defeated by the Undertaker at WrestleMania VII, which began Undertaker's undefeated streak at WrestleMania.[51] In January 1992, he competed in the Royal Rumble for the vacant WWF Championship, but lasted only three minutes before being eliminated by Undertaker.[52] Snuka left the WWF soon after, his last recorded match being a loss to Shawn Michaels at the Los Angeles Sports Arena on February 8, 1992.[53]

In the midst of his ECW career, Snuka once again returned to the WWF on September 25, 1993, defeating Brian Christopher at a Madison Square Garden house show. He returned to television two nights later, defeating Paul Van Dale via Superfly Splash on the September 27 episode of Monday Night Raw. The following week on Raw, Snuka participated in a battle royal for the vacant Intercontinental Championship, in which he was eliminated by Rick Martel before departing the company.[54]

NWA Eastern Championship Wrestling (1992–1994)

[edit]Heavyweight champion (1992)

[edit]After leaving the WWF in March 1992, Snuka toured with various smaller organizations and played a role in the formation of Tod Gordon's Philadelphia-based Eastern Championship Wrestling (ECW) organization along with fellow veterans Don Muraco and Terry Funk. Snuka made his ECW debut as a fan favorite at a live event on April 25. He won his first match, a battle royal to qualify for the ECW Heavyweight Championship match against Salvatore Bellomo, the winner of the other battle royal. Immediately after, Snuka defeated Bellomo to become the promotion's first heavyweight champion.[55] A day later, he dropped the title to Johnny Hotbody.[56]

He returned to ECW on July 14, where he defeated Hotbody to regain the heavyweight title, winning it for a second time.[57] He made his first successful title defense, against Mr. Sandman, on July 15.[58] Snuka held the title for the next two months, defeating challengers like Super Destroyer No. 1[59][60] and King Kaluha,[61] before losing the title to Muraco on September 30.[62] Snuka unsuccessfully challenged Muraco for the title in a rematch on October 24,[63] after which he turned into a villain by feigning confrontation with color commentator Stately Wayne Manor and then attacking ECW owner Tod Gordon with a chair.[64] Snuka took on Hunter Q. Robbins III as his manager and closed the year with a loss to Davey Boy Smith on December 19.[65]

Television champion and various feuds (1993–1994)

[edit]Snuka became a member of Paul E. Dangerously's new faction Hotstuff International on the debut episode of the company's eponymous television program Eastern Championship Wrestling on April 6[64] and won an eight-man tournament for the vacant television championship by defeating Larry Winters, the undefeated Tommy Cairo and Glen Osbourne.[66] Snuka frequently teamed with his stablemates Eddie Gilbert and Muraco. Snuka made his first televised title defense against Osbourne on the May 25 episode of Eastern Championship Wrestling, where Snuka retained the title.[67] Snuka successfully defended the title against J.T. Smith and the NWA Pennsylvania Heavyweight champion Tommy Cairo at Super Summer Sizzler Spectacular,[68] while also defending the title on Eastern Championship Wrestling.[67] Snuka lost the title to Terry Funk in a brutal steel cage match at NWA Bloodfest.[69]

Snuka's next notable match took place at The Night the Line Was Crossed in 1994, where he faced rising star Tommy Dreamer in an infamous match. During the match, Dreamer kicked out of a pinfall attempt by Snuka after a Superfly splash, thus marking one of the few times in wrestling history that an opponent kicked out of Snuka's finishing move.[70] Snuka still managed to win by delivering three splashes. Snuka continued his assault on Dreamer after the match,[71][72] which began a feud between the two. Snuka lost to Dreamer on March 5[73] before beating him in a steel cage match at Ultimate Jeopardy.[74] Snuka wrestled his last ECW match at Hardcore Heaven in August, where he and the Tazmaniac picked up a tag team victory over the Pitbulls.[75] Later that month, ECW was taken over by Paul Heyman, who renamed it Extreme Championship Wrestling.[1]

World Championship Wrestling appearances (1993, 2000)

[edit]Snuka wrestled for one night at WCW's Slamboree 1993: A Legends' Reunion on May 23, 1993, teaming with Don Muraco and Dick Murdoch against Wahoo McDaniel, Blackjack Mulligan, and Jim Brunzell in a no contest.[76]

Snuka also appeared on WCW Monday Nitro January 10, 2000, where he gave Jeff Jarrett a Superfly splash off the top of a steel cage, giving Jarrett a concussion on the process.[77][78]

Independent circuit and retirement (1995–2015)

[edit]

Snuka continued to spend much of his time with East Coast Wrestling organizations through the mid-1990s and into the 2000s. During this time, he wrestled the Metal Maniac in a series of matches that spanned across many independent wrestling promotions, winning most of these matches. On August 15, 1997, Snuka defeated the Masked Superstar at the IWA Night of the Legends show in Kannapolis, North Carolina via disqualification when his opponent hit special guest referee Ricky Steamboat.[79][80]

Snuka also participated at the first X Wrestling Federation TV tapings, accompanying his son, Jimmy Snuka Jr. to the ring for matches,[81] including one match where they both delivered a Superfly splash to prone opponents.[82] On June 22, 2002, Snuka won the International Wrestling Superstars (IWS) United States Championship by pin fall against King Kong Bundy in Atlantic City, New Jersey.[83] On April 3, 2004, Snuka and Kamala fought to a no-contest at the International Wrestling Cartel's first-annual "Night Of Legends" event in Franklin, Pennsylvania.[84]

In 2004, Snuka made an appearance for Total Nonstop Action Wrestling at their Victory Road pay-per-view as Piper's guest on Piper's Pit.[85]

On July 1, 2006, Snuka wrestled for 1PW's Fight Club 2 event where he teamed with Darren Burridge to defeat Stevie Lynn and Jay Phoenix.[86]

On March 28, 2009, Snuka again participated at the IWC's "Night Of Legends" event, where he defeated former rival Orton.[87] On August 1, Snuka teamed with Jon Bolen, Jimmy Vegas, and Michael Facade (with Dominic DeNucci) to defeat James Avery, Logan Shulo, Shane Taylor and Lord Zoltan (with Mayor Mystery) at IWC's "No Excuses 5" in Elizabeth, Pennsylvania.[88] On November 28, 2009, he teamed with his son at an NWA Upstate event in Lockport, New York. They defeated the NWA Upstate Tag Team champions Hellcat and Triple X in a non-title match.[89]

In 2011, Jimmy Snuka competed at JCW: Icons and Legends event in a battle royal match won by Zach Gowen.[90] On May 11, 2014, Snuka teamed up with the Patriot to defeat the team of Brodie Williams and Mr. TA at a Big Time Wrestling event.[86] Snuka's last match was at an ECPW event, where he teamed up with Frankie Flow to defeat the team of Andrew Anderson and Jason Knight on May 15, 2015, just 3 days before his 72nd birthday.

Sporadic WWE appearances (1996−2009)

[edit]

Snuka was inducted into the WWF Hall of Fame class of 1996.[1] Afterward, he competed at the 1996 Survivor Series.[91] Snuka received a lifetime achievement award from WWE at Madison Square Garden on WWE Raw, August 26, 2002.

In 2005, he appeared at the WWE Homecoming, where he delivered a Superfly splash to Rob Conway. He was a part of the Taboo Tuesday pay-per-view, where fans voted for him (ahead of Kamala and Jim Duggan) to team with Eugene against Conway and Tyson Tomko.[1] Snuka won the match, pinning Conway after a Superfly splash. He appeared at the 2007 WWE draft edition of Raw in a vignette for Vince McMahon appreciation night.[92] On June 24, 2007, Snuka was introduced as Sgt. Slaughter's tag team partner in the open invitational match for the WWE Tag Team Championship at Vengeance, but he was ultimately pinned by his son, Deuce.[1] In 2008, Snuka appeared in the Royal Rumble. He was in the match less than five minutes and primarily focused his efforts on onetime nemesis, Piper. Both were quickly eliminated by the next entrant, Kane.[93]

On the March 2, 2009, episode of Raw, he was attacked by Chris Jericho during a parody of Piper's Pit.[94] This was part of a storyline where Jericho was disrespecting and attacking legends.[95] Two weeks later, on the March 16, 2009, episode of Raw, Snuka, Piper, Ric Flair and Steamboat attacked Jericho.[96] At WrestleMania 25 on April 5, 2009, Snuka teamed with Steamboat and Piper to face Jericho in a legends of WrestleMania handicap match with Flair in their corner. Snuka was the first man eliminated by Jericho, who eventually won the match.[97]

Personal life

[edit]Snuka was the part-owner of Body Slam University and Coastal Championship Wrestling in South Florida with Dan Ackerman and Bruno Sassi.[98] He wrote an autobiography, Superfly: The Jimmy Snuka Story, which was released on December 1, 2012.[99]

Family

[edit]Snuka was married three times.[100] His second marriage was to Sharon Ili and they had two daughters Liana Snuka and Sarona. Through his marriage to Sharon, Snuka was part of the Anoaʻi wrestling family.[7] He has two granddaughters named Milaneta Polamalu and Maleata Polamalu and he has a stepdaughter Ata Louise, Sharon's third daughter.[100] His third marriage was to Carole on September 4, 2004.[100] He was the stepfather to Carole's three children: Bridget, Richard, and Dennis.[100]

Nancy Argentino's death and murder allegations

[edit]On May 10, 1983, a few hours after defeating José Estrada at a WWF television taping at the Lehigh County Agricultural Hall in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Snuka placed a call for an ambulance. When emergency personnel arrived at his room at the George Washington Motor Lodge, they found that his girlfriend and mistress, Nancy Argentino, had been injured. She was transported to Allentown's Sacred Heart Medical Center, where she died due to "undetermined craniocerebral injuries." The coroner's report stated that Argentino, 23, died of traumatic brain injuries consistent with a moving head striking a stationary object. Autopsy findings show Argentino had more than two dozen cuts and bruises—a possible sign of serious domestic abuse—on her head, ear, chin, arms, hands, back, buttocks, legs, and feet. Forensic pathologist Isidore Mihalakis, who performed the autopsy, wrote at the time that the case should be investigated as a homicide until proven otherwise. Deputy Lehigh County coroner Wayne Snyder later said, "Upon viewing the body and speaking to the pathologist, I immediately suspected foul play and so notified the district attorney."[101] Snuka had previously been arrested for beating Argentino on January 18, 1983, at a hotel in Salina, New York, fighting off several deputies who were called by the hotel's night manager. Although Argentino initially sought prosecution, she later denied wanting such; in a later-released file from the murder investigation, an officer's note indicates that “Vince McMahon tried to talk her out of making the complaint against Snuka.”

Snuka was the only suspect involved in the subsequent investigation. Although charges were not pressed at the time against Snuka, the case was left officially open. In 1985, Argentino's parents won a $500,000 default judgment against Snuka in U.S. District Court in Philadelphia. Snuka appears not to have ever paid, claiming financial inability.[102] On June 28, 2013, Lehigh County District Attorney Jim Martin announced that the still-open case would be reviewed by his staff.[101] On January 28, 2014, Martin announced that the case had been turned over to a grand jury.[103]

On September 1, 2015, 32 years after the incident, Snuka was arrested and charged with third-degree murder and involuntary manslaughter for Argentino's death.[104][105] It is the oldest case to result in charges in Lehigh County's history.[104] On October 7, 2015, Snuka's lawyers agreed to forego a preliminary hearing, which the prosecution contended was a waste of court resources, given the thorough grand jury investigation. In return, they received transcripts and other evidence from that investigation, which defense attorney Robert J. Kirwan II said would be much more helpful in preparing Snuka's case than a hearing would have been.[106]

On November 2, 2015, Snuka pleaded not guilty before Judge Kelly Banach.[107] A hearing to determine Snuka's competency for trial began in May 2016. Snuka's attorneys argued that a forensic psychologist found Snuka's mental and physical health to be deteriorating. Prosecutors countered by showing a tape of Snuka performing wrestling moves at a May 2015 match.[6] On June 1, 2016, Banach ruled that Snuka was not mentally competent to stand trial for the murder and that a new hearing would be held six months later to re-evaluate his competency, though his attorneys maintained that his condition would not improve over time.[11] Banach dismissed the charges on January 3, 2017, deeming Snuka mentally unfit to stand trial.[13]

Illness and death

[edit]In August 2015, Snuka's wife, Carole, announced that he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. As a result, he had surgery to remove his lymph nodes, part of his stomach and all apparent cancer. She said they both expected he would fully recover after "a long road ahead".[108] Following his arrest his attorney, William E. Moore, told reporters Snuka had dementia, stemming from wrestling-related injuries, to the point of being unfit for trial,[109] and a judge ultimately agreed.[11]

In July 2016, Carole Snuka, acting as representative for her husband, joined a class action lawsuit filed against WWE which alleged that wrestlers sustained "long term neurological injuries" and that the company "routinely failed to care" for them and "fraudulently misrepresented and concealed" the nature and extent of those injuries. The suit is litigated by attorney Konstantine Kyros, who has been involved in a number of other lawsuits against WWE.[110] According to a court document filed by Kyros in November 2016, Snuka was diagnosed with "chronic traumatic encephalopathy or a similar disease". WWE challenged the filing, stating that "no medical report was included" in it. Since the September 2007 autopsy on Chris Benoit that detected he had CTE, the Kyros Law Firm has represented over 60 wrestlers or estates of deceased wrestlers (including Carole Snuka) in litigation against the WWE.[111] The lawsuit was dismissed by US District Judge Vanessa Lynne Bryant in September 2018.[112]

On December 2, 2016, it was announced that Snuka was in hospice and had six months left to live, due to a terminal illness.[12] He died on January 15, 2017, at age 73 in Pompano Beach, Florida.[113]

Other media

[edit]Video games

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Legends of Wrestling | Video game debut |

| 2002 | Legends of Wrestling II | |

| 2003 | WWE SmackDown! Here Comes the Pain | |

| 2004 | Showdown: Legends of Wrestling | |

| WWE SmackDown! vs. Raw | ||

| 2005 | WWE WrestleMania 21 | |

| 2009 | WWE Legends of WrestleMania | |

| 2010 | WWE SmackDown vs. Raw 2011 | |

| 2011 | WWE All Stars |

Championships and accomplishments

[edit]

- All Japan Pro Wrestling

- World's Strongest Tag Determination League (1981) – with Bruiser Brody[114]

- World's Strongest Tag Determination League Technique Award (1988) – with Tiger Mask II[115]

- All-Star Wrestling Alliance / American States Wrestling Alliance

- ASWA Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[116]: 81

- American Wrestling Association

- Catch Wrestling Association

- CWA British Commonwealth Championship (1 time)[117]

- Cauliflower Alley Club

- Continental Wrestling Association

- East Coast Pro Wrestling

- ECPW Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[119]

- Eastern Championship Wrestling

- Georgia Championship Wrestling

- International Wrestling Superstars

- IWS United States Championship (1 time)[83]

- Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling

- National Championship Wrestling

- NCW Tag Team Championship (1 time) – with Johnny Gunn[116]: 68

- National Wrestling Federation

- NWF Heavyweight Championship (1 time, final)[116]: 50

- National Wrestling League

- NWL Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[124]

- Northeast Wrestling

- NEW Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[116]: 52

- NWA All-Star Wrestling

- NWA Big Time Wrestling

- NWA Tri-State Wrestling

- NWA West Virginia/Ohio

- NWA West Virginia/Ohio Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[130]

- New England Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2010[131]

- Pacific Northwest Wrestling

- Pro Wrestling Illustrated

- Match of the Year (1982) vs. Bob Backlund in a cage match on June 28[22]: 369 [133]

- Most Popular Wrestler of the Year (1983)[134]

- Tag Team of the Year (1980) with Ray Stevens[133]

- Ranked No. 75 of the top 500 singles wrestlers in the PWI 500 in 1993[135]

- Ranked No. 29 of the top 500 singles wrestlers during the PWI Years in 2003[136]

- Pro Wrestling This Week

- Wrestler of the Week (January 25–31, 1987)[137]

- Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame

- Class of 2012[16]

- Ring Around The Northwest Newsletter

- Universal Superstars of America

- USA Heavyweight Championship (2 times)[116]: 46

- USA Pro Wrestling

- USA Pro New York Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[139]

- World Wide Wrestling Alliance

- World Wrestling Federation

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

- Tag Team of the Year (1981) with Terry Gordy[140]

- Best Flying Wrestler (1981)[141]

- Best Wrestling Maneuver (1981, 1983) Superfly Splash[141]

- Most Unimproved (1984)[142]

- Worst on Interviews (1984)[142]

- Most Washed Up Wrestler (1984)[140]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Reiher legally changed his surname to Snuka.[8]

- ^ Jimmy Snuka's reigns occurred while the promotion was a National Wrestling Alliance affiliate named Eastern Championship Wrestling, and was prior to the promotion becoming Extreme Championship Wrestling and the title being declared a world title by ECW.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j ""Superfly" Jimmy Snuka bio". WWE. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Meltzer, Dave (1996). The Wrestling Observer's Who's Who in Pro Wrestling. Wrestling Observer. pp. 111–112.

- ^ a b c d Historical Dictionary of Wrestling. Scarecrow Press. 2014. p. 272. ISBN 9780810879263.

- ^ a b Shields, Brian; Sullivan, Kevin (2009). WWE Encyclopedia. DK. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-7566-4190-0.

- ^ Shields, Brian (2010). Main Event: WWE in the Raging 80s. Simon & Schuster. p. 51. ISBN 978-1416532576.

- ^ a b Mason Schroeder, Laurie (May 13, 2016). "Psychologist says Snuka 'shell of a man,' but video shows 'Superfly Splash' from last year". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ a b "Superfly Snuka and the Anoa'i Family".

- ^ Mooneyham, Mike (January 20, 2013). "Superfly Jimmy Snuka soars again in new book". The Post and Courier. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ Gamiz, Manuel Jr. (September 1, 2015). "Wrestling legend Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka to be charged in girlfriend's 1983 death". The Morning Call. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ "Ex-wrestler Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka charged in girlfriend's 1983 death". The Record (Bergen County). Associated Press. September 1, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

Snuka, now 72 and living in Waterford Township, N.J., wrote about Argentino's death in his 2012 autobiography, maintaining his innocence and saying the episode had ruined his life.

- ^ a b c "Judge: Former pro wrestler "Superfly" Snuka incompetent to stand trial". CBS News. June 1, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Schroeder, Laurie Mason (December 2, 2016). "Testimony: Jimmy Snuka in hospice, has 6 months to live". The Morning Call. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Mason Schroeder, Laurie; Gamiz, Manuel Jr. (January 3, 2017). "Judge dismisses homicide charges against Jimmy Snuka". The Morning Call. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ Snuka, Jimmy; Chattman, Jon (2012). Superfly: The Jimmy Snuka Story. Triumph Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-1600787584.

I was born James Wiley Smith in the Fiji Islands, or Viti, as we call it, on May 18, 1943.

- ^ Snuka, Jimmy; Chattman, Jon (2012). Superfly: The Jimmy Snuka Story. Triumph Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-1600787584.

- ^ a b Oliver, Greg. "Jimmy "Superfly" Snuka". The Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Slagle, Steve. "Jimmy "Superfly" Snuka". The Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on April 21, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ World Wrestling Federation (Producer), Snuka, J. (Writer), & Graham, D. (Director). (1982). Spectrum wrestling [Motion picture]. USA: World Wrestling Federation.

- ^ Solomon, Brian (2010). WWE Legends. Simon and Schuster. p. 79. ISBN 978-1451604504.

- ^ a b Snuka, Jimmy (2012). Superfly: The Jimmy Snuka Story. Triumph. p. 62. ISBN 978-1617499807.

- ^ a b Hoops, Brian (July 6, 2015). "On this day in pro wrestling history (July 6): Terry Gordy & Jimmy Snuka win belts, Santana vs. Valentine, Goldberg vs. Hogan seta WCW record". Figure Four Wrestling. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Cawthon, Graham (2013). The History of Professional Wrestling: The Results WWF 1963–1989. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-4928-2597-5.

- ^ Kane III, Sheldon (August 17, 2004). "Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka vs. Ray 'The Crippler' Stevens: December 28, 1982". TheHistoryofWWE.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ Solomon, Brian (2010). WWE Legends. Simon and Schuster. p. 80. ISBN 978-1451604504.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham. "Rings Results: 1982". TheHistoryofWWE.com. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Sugar, Bert Rudolph; Napolitano, George (1984). The Pictorial History of Wrestling: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Gallery Books. p. 76. ISBN 0-8317-3912-6.

- ^ Shoemaker, David (2013). The Squared Circle: Life, Death, and Professional Wrestling. Penguin. p. 168. ISBN 978-1101609743.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham. "Ring Results: 1983". TheHistoryofWWE.com. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Foley, Mick. Have A Nice Day: A Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks (p.34)

- ^ Kapur, Bob (July 2, 2012). "Behind the lens of WWE's former photo chief". Slam! Wrestling. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Waldman, John (July 27, 2005). "'80s DVD falls short of expectations". Slam! Wrestling. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Molina, Joshua (January 6, 2015). "WWF Tuesday Night Titans Episode 3 Review". Figure Four Wrestling. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Sullivan, Greg (August 1, 2015). "Chewing the Turnbuckle: 'Rowdy' Roddy Piper talks about visiting Fall River, hitting 'Superfly' Snuka in the head with a coconut, his amazing movie fight with Keith David, and Georgia Championship Wrestling". The Herald News. Fall River, Massachusetts. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Cohen, Daniel; Cohen, Susan (1985). Wrestling Superstars. Archway. p. 34. ISBN 0-671-60648-4.

- ^ Settee, Alexander (September 18, 2008). "The War To Settle The Score: February 18, 1985". The History of WWE. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham. "Ring Results: 1985". TheHistoryofWWE.com. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ^ "Bob Orton, Jr". WWE. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ "Full WrestleMania I Results". WWE. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ "Hulk Hogan's Rock 'N' Wrestling". TV.com. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Reynolds, R.D. (2003). WrestleCrap: The Very Worst of Professional Wrestling. ECW Press. p. 48. ISBN 1-55490-544-3.

- ^ Hoops, Brian (June 30, 2008). "Nostalgia Review: AWA Battle By the Bay". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Schire, George (2010). Minnesota's Golden Age of Wrestling: From Verne Gagne to the Road Warriors. Minnesota Historical Society. p. 156. ISBN 978-0873516204.

- ^ a b Shields, Brian (2010). Main Event: WWE in the Raging 80s. Simon & Schuster. p. 53. ISBN 978-1416532576.

- ^ Zbyszko, Larry (2008). Adventures in Larryland!. ECW Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1554903221.

- ^ Shields, Brian (2010). Main Event: WWE in the Raging 80s. Simon & Schuster. p. 54. ISBN 978-1416532576.

- ^ a b Cawthon, Graham. "Ring Results: 1989". TheHistoryofWWE.com. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ "Full Event Results: SummerSlam 1989". WWE.com. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ "Wrestlemania VI results". World Wrestling Entertainment. Archived from the original on February 22, 2009. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- ^ Lyon, Stephen (September 20, 2010). "WWE Vintage Collection TV Report – 1990 IC Title Tournament". Figure Four Wrestling. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ "Survivor Series Flashback – 20 yrs. ago (11–22–90): Undertaker's WWE debut, Gobbledy Gooker, Hogan & Warrior, Top 10 Things – wrestlers on 'Old School' Raw, Second generation wrestlers". Pro Wrestling Torch. November 10, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ "Wrestlemania VII results". WWE.com. World Wrestling Entertainment. Archived from the original on March 15, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- ^ Bryden, Jason (January 19, 2012). "Jason Bryden looks at the 1992 Royal Rumble". Poughkeepsie Journal. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham. "Ring Results: 1992". TheHistoryofWWE.com. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Cawthon, Graham. "Ring Results: 1993". TheHistoryofWWE.com. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ "ECW results - April 25, 1992". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW results - April 26, 1992". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW results - July 14, 1992". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW results - July 15, 1992". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW results - August 12, 1992". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW results - September 12, 1992". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW results - August 22, 1992". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW results - September 30, 1992". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW results - October 24, 1992". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ a b "ECW 1992-1993 Results". The History of WWE. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Morrisville Mayhem results". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW Television Championship Tournament 1993". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ a b "ECW: 1993 Results". Online World of Wrestling. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Super Summer Sizzler results". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "NWA Bloodfest: Part 1 results". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ The first opponent to kick out from Snuka's finishing move was Kevin Von Erich during a televised non-title match on Georgia Championship Wrestling; aired September 5, 1981

- ^ "ECW 1994 Results". The History of WWE. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "The Night The Line was Crossed results". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "ECW results - March 5, 1994". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Ultimate Jeopardy 1994 results". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Hardcore Heaven 1994 results". Pro Wrestling History. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Jimmy Snuka". Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ Russo, Ric (January 21, 2000). "What Ever Happened To . . . Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka?". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Ravens, Andrew (January 11, 2025). "Jeff Jarrett Recalls the Worst Injury of His Career". 411Mania. Retrieved January 25, 2025.

- ^ Apter, Bill. "Names Makin' News." Inside Wrestling. Holiday 1997: 9+.

- ^ Smith, Wes (August 17, 1997). "My Night with the Legends". Solie's Tuesday Morning Report; Solie.org. 3 (208).

- ^ Snuka, Jimmy; Chattman, Jon (2012). "The Jimmy Snuka Timeline". Superfly: The Jimmy Snuka Story. Triumph Books. ISBN 978-1600787584.

November 2001: Orlando, FL—Jimmy manages his son, Jimmy Snuka Jr., at the first and only set of XWF shows at Universal Studios

- ^ X Wrestling Federation (Producer) (November 14, 2001). The Lost Episodes of the XWF (DVD). Orlando, Florida: Amazon.com.

- ^ a b "Five new Champions are Crowned at Wrestlefest 2002!". IWSwrestling.net. June 2002. Archived from the original on August 3, 2002.

- ^ "2004 Results". International Wrestling Cartel. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Clevett, Jason (November 8, 2004). "Victory Road Bombs". Slam! Wrestling. Archived from the original on May 19, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "Matches: Jimmy Snuka". CageMatch. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ "Night of Legends 2009 – March 28th, 2009". International Wrestling Cartel. Archived from the original on November 21, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ^ "No Excuses 5 – August 1st, 2009". International Wrestling Cartel. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ^ NWA New York (Producer) (November 28, 2009). NWA New York Raging Gladiator Wrestling III (DVD). Lockport, New York: PridesProductions.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ^ "Radican's JCW 'Legends & Icons' iPPV Review". Pro Wrestling Torch. August 3, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ "Full Event Results: Survivor Series 1996". World Wrestling Entertainment. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ "One Wild Night". World Wrestling Entertainment. June 11, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Caldwell, James (January 27, 2008). "Caldwell's WWE Royal Rumble Report 1/27: Ongoing "virtual time" coverage of debut HD PPV". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Golden, Hunter (March 2, 2009). "Raw Results 3/2/09". Wrestleview. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Jericho, Chris (2014). The Best in the World: At What I Have No Idea. Penguin. p. 104. ISBN 978-0698162143.

- ^ Golden, Hunter (March 16, 2009). "Raw Results 3/16/09". Wrestleview. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ Keller, Wade (April 5, 2009). "Keller's WrestleMania 25 Results". Pro Wrestling Torch. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Curreri, Gary (July 26, 2009). "Hoping To Lay The Smack Down". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ "Exclusive preface of 'Superfly: The Jimmy Snuka Story'". USA Today. November 6, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Snuka, Jimmy; Chattman, Jon (2012). Superfly: The Jimmy Snuka Story. Triumph Books. ISBN 978-1617499807.

- ^ a b Clark, Adam; Amerman, Kevin (June 28, 2013). "DA taking 'fresh look' at death of 'Superfly' Snuka mistress". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Muchnick, Irv (2007). Wrestling Babylon: Piledriving Tales of Drugs, Sex, Death, and Scandal. ECW Press. pp. 125–131. ISBN 978-1550227611.

- ^ Clark, Adam; Amerman, Kevin (January 28, 2014). "Grand jury to review death of Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka's girlfriend". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Gamiz, Manuel Jr. (September 1, 2015). "Wrestling legend Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka charged in girlfriend's 1983 death". The Morning Call. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ "Former Pro Wrestling Star 'Superfly' Snuka Charged in Girlfriend's 1983 Lehigh County Death". 6ABC.com. Allentown, Pennsylvania: ABC Inc. (WPVI-TV). September 2, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ Gamiz, Manuel Jr.; Hall, Peter (October 7, 2015). "Attorney: Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka 'looking forward to clearing his name'". The Morning Call. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ Dekok, David (November 2, 2015). "Jimmy Snuka pleads not guilty to murdering girlfriend in 1983". canoe.com. Reuters. Archived from the original on November 3, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ "Wife: Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka diagnosed with stomach cancer". FoxNews. August 3, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Sandoval, Edgar; McShane, Larry (September 2, 2015). "Jimmy (Superfly) Snuka's lawyer argues all those years getting bashed in the ring make him unfit to stand trial for girlfriend's 1983 murder". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ Bieler, Des (July 19, 2016). "Dozens of wrestlers sue WWE over CTE, effects of traumatic brain injuries". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ Rapaport, Daniel (November 4, 2017). "Judge throws out lawsuit against WWE by ex-pro wrestlers over concussions". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ Collins, Dave (September 19, 2018). "Judge throws out lawsuit against WWE by ex-pro wrestlers over concussions". The Denver Post. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- ^ McCausland, Phil (January 15, 2017). "Controversial Wrestler Jimmy 'Superfly' Snuka Dead at 73". NBCNews.com. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Titleholder" (in Japanese). All Japan Pro Wrestling. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ "PUROLOVE.com". www.purolove.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2000). Wrestling Title Histories (4th ed.). Archeus Communications. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ "CWA British Commonwealth Championship". CageMatch.net. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "List of CAC Award Winners". Cauliflower Alley Club. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ "Title Histories". East Coast Pro Wrestling. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ cite web|url= https://www.cagematch.net/?id=26&nr=2611&page=2

- ^ "WWE United States Championship". Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ "Mid-Atlantic Tag Team Title". Mid-Atlantic Gateway. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ "WCW World Tag Team Championship History (1980–2000)". World Championship Wrestling. Archived from the original on November 10, 2000. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ "National Wrestling League Heavyweight Champion History". National Wrestling League. Archived from the original on June 26, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ Will, Gary; Duncan, Royal (2000). "Texas: NWA Texas Heavyweight Title [Von Erich]". Wrestling Title Histories: professional wrestling champions around the world from the 19th century to the present. Pennsylvania: Archeus Communications. pp. 268–269. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ "NWA Texas Heavyweight Title". Wrestling-Titles. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ Will, Gary; Duncan, Royal (2000). "Texas: NWA Texas Tag Team Title [Von Erich]". Wrestling Title Histories: professional wrestling champions around the world from the 19th century to the present. Pennsylvania: Archeus Communications. pp. 275–276. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ "NWA Texas Tag Team Title [E. Texas]". wrestling-titles.com. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ^ "NWA Tri-State Heavyweight Title (Oklahoma)". Wrestling-Titles.com. Puroresu Dojo. 2003.

- ^ "NWA Tri-State Heavyweight Title (W. Virginia, Ohio, & Kentucky)". Wrestling-Titles.com. Puroresu Dojo. 2003.

- ^ "New England Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame". Facebook. New England Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame. May 12, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

The class of 2010 for the New England pro wrestling Hall of Fame included Jimmy "Superfly" Snuka, "Living Legend" Larry Zbyszko, The late Rocko Rock and Johnny Grunge (Public Enemy), Sonny Goodspeed, Kenny Casanova, Paul Richard, Tony Ulysses, Bad Boy Billy Black, Maverick Wild, Dr. Heresy, The late Mr.Biggs, John Rambo, Bull Montana, The late Georgiann Makropoulos, "The Duke of Dorchester" Pete Doherty, "Dangerous" Danny Davis, Angelo Savoldi, Mario Savoldi, "Jumpin" Joe Savoldi and Tommy Savoldi.

- ^ "NWA Pacific Northwest Tag Team Title". Wrestling-Titles.com. Puroresu Dojo. 2003.

- ^ a b "Achievement Awards: Past Winners". Pro Wrestling Illustrated. London Publishing Co.: 85 March 1996. ISSN 1043-7576.

- ^ "Achievement Awards: Past Winners". Pro Wrestling Illustrated. London Publishing Co.: 87 March 1996. ISSN 1043-7576.

- ^ "Pro Wrestling Illustrated (PWI) 500 for 2007". Internet Wrestling Database. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ "PWI 500 of the PWI Years". Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Pedicino, Joe; Solie, Gordon (hosts) (January 31, 1987). "Pro Wrestling This Week". Superstars of Wrestling. Atlanta, Georgia. Syndicated. WATL.

- ^ a b Rodgers, Mike (2004). "Regional Territories: PNW #16". KayfabeMemories.com.

- ^ "USA Pro/UXW New York Heavyweight Title". Wrestling-Titles.com. Puroresu Dojo. 2003.

- ^ a b Meltzer, Dave (January 26, 2011). "Biggest issue of the year: The 2011 Wrestling Observer Newsletter Awards Issue". Wrestling Observer Newsletter. Campbell, CA: 1–40. ISSN 1083-9593.

- ^ a b ""Superfly" Jimmy Snuka Soars into the TWA on Apr 11th". Tri-State Wrestling Alliance. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Meltzer, Dave (January 22, 1996). "Results of the 1995 Observer Newsletter Awards". Wrestling Observer Newsletter.

Further reading

[edit]- Foley, Mick (1999) Have a Nice Day: A Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks. ReganBooks. ISBN 0-06-039299-1.

External links

[edit]- "Official website". Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- "WWE Profile". Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- Jimmy Snuka's profile at WWE , Cagematch , Internet Wrestling Database

Jimmy Snuka

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Birth and Upbringing

James Reiher Snuka was born James Wiley Smith on May 18, 1943, in Fiji to Louisa Smith.[10][11] His biological father was Charles Thomas, with whom his mother had an extramarital relationship, though Thomas remained married to another woman.[12] Snuka's mother subsequently married, leading to his adoption of the surname Reiher from his stepfather.[13] As a child, Snuka's family relocated from Fiji to the Marshall Islands before settling in Hawaii around age 11.[14][15] In Hawaii, he encountered formal education for the first time and faced adaptation challenges in the classroom but thrived athletically, particularly in football.[15] His upbringing involved an adventurous lifestyle amid the islands, including cliff diving and emulating Tarzan, fostering a fearless disposition that echoed in his later persona.[14] In Hawaii during the 1960s, Snuka pursued competitive bodybuilding, securing titles such as Mr. Hawaii, Mr. North Shore, and Mr. Waikiki.[16][12] These early athletic endeavors laid the foundation for his physical development and entry into professional sports.[13]Entry into Sports and Amateur Background

Snuka engaged in amateur bodybuilding in Hawaii during the 1960s, competing and training rigorously to build his physique.[17][18] He achieved success by winning the Hawaiian Islands Bodybuilding Championship, showcasing his dedication to strength training and physical conditioning.[19] This period marked his initial foray into competitive sports, emphasizing feats of strength and muscle development that later informed his athletic style in professional wrestling.[20] While working and training at Dean Ho's gym in Hawaii, Snuka encountered professional wrestlers performing in the region, sparking his interest in the sport as an extension of his bodybuilding prowess.[3][18] These interactions, combined with his established amateur foundation in bodybuilding, provided the physical base and motivation for transitioning toward professional athletics, though he had no documented involvement in other amateur disciplines like football or track prior to this.[2]Professional Wrestling Career

Early Career in Regional Promotions (1968–1979)

Jimmy Snuka debuted professionally in Hawaii in 1969 under the ring name Jimmy Kealoha, facing Maxwell "Bunny" Butler in his first match.[2] He adopted the Jimmy Snuka moniker shortly thereafter and relocated to the mainland United States, competing primarily in the NWA Pacific Northwest Wrestling territory based in Portland, Oregon, under promoter Don Owen. In this promotion, Snuka refined his high-flying style against seasoned opponents, establishing a reputation for athleticism and resilience.[3] Snuka's success in the Pacific Northwest was marked by multiple championship reigns. On November 16, 1973, he defeated Bull Ramos to win his first NWA Pacific Northwest Heavyweight Championship, a title he would capture six times overall.[2] He also secured the NWA Pacific Northwest Tag Team Championship eight times, including six reigns partnering with Dutch Savage and two with Frankie Laine, highlighted by victories such as the October 27, 1973, win over Bull Ramos and Ripper Collins.[21] Feuds with wrestlers like Ramos and Collins defined his tenure, including a mid-1974 hair vs. hair match victory against Collins.[22] By 1977, Snuka expanded to the Texas-based NWA Big Time Wrestling promotion in Dallas, where he teamed with Gino Hernandez to defeat Bruiser Brody and Mike York on August 27, 1977, for the NWA Texas Tag Team Championship.[2] During this period, he also won the NWA Texas Heavyweight Championship, demonstrating versatility across regional territories.[23] These accomplishments in Pacific Northwest and Texas promotions solidified Snuka's standing as a rising star in the National Wrestling Alliance's territorial system before transitioning to broader exposure.[24]National Breakthrough and Feuds (1979–1981)

In early 1979, Jimmy Snuka achieved prominence in Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling as one half of the NWA World Tag Team Champions alongside Paul Orndorff, holding the titles after defeating the Andersons in late 1978.[25] Their reign showcased Snuka's athleticism in tag team competition, including defenses against teams like Ric Flair and Big John Studd.[26] On July 18, 1979, Snuka underwent a dramatic heel turn during a televised match, aligning with manager Buddy Rogers and adopting a ruthless style that abandoned his signature high-flying maneuvers in favor of illegal tactics and aggression.[25] This shift positioned him as a villain, culminating in his victory in a tournament final against Ricky Steamboat on September 1, 1979, in Charlotte, North Carolina, to capture the vacant NWA United States Heavyweight Championship.[27] [28] Snuka's reign as U.S. Champion, lasting until April 1980, featured intense feuds, most notably a brutal series with Ric Flair marked by bloody, hard-fought matches that elevated both wrestlers' profiles across the territory.[29] Key encounters included Snuka retaining the title against Flair on November 4, 1979, amid ongoing violence that drew significant fan attention.[2] He also defended against challengers like Ricky Steamboat in 1980 bouts that highlighted his evolving aggressive persona.[30] Transitioning to tag team action, Snuka partnered with Ray "The Crippler" Stevens to win the NWA World Tag Team Championship in late 1979, extending their successful run into early 1981 with defenses that solidified Snuka's status as a top draw.[25] By mid-1981, Snuka moved to Georgia Championship Wrestling, where on July 6, 1981, he teamed with Terry Gordy to defeat Ted DiBiase and Steve O for the NWA National Tag Team Championship, marking his expansion beyond Mid-Atlantic territories.[2] These achievements and rivalries represented Snuka's breakthrough to national recognition within the NWA ecosystem, showcasing his versatility from high-flyer to dominant heel.[31]World Wrestling Federation Peak (1982–1985)

Jimmy Snuka joined the World Wrestling Federation (WWF) in early 1982, making his debut on March 12 by defeating Barry Hart in All Star Wrestling.[2] As a high-flying babyface, Snuka quickly rose to prominence, challenging WWF Champion Bob Backlund for the title. On June 28, 1982, at Madison Square Garden, Snuka faced Backlund in a steel cage match for the WWF Championship; despite leaping from the top of the cage in a dramatic spot, Snuka lost the bout.[22] This match highlighted Snuka's athleticism and aerial prowess, including his signature "Superfly Splash," which became a staple of his performances. In 1983, Snuka engaged in a high-profile feud with Intercontinental Champion Don Muraco, culminating in a steel cage title match on October 17 at Madison Square Garden. Muraco retained the championship, but post-match, Snuka climbed the cage and executed a body splash onto the prone champion from the top, an iconic moment that electrified the crowd and cemented Snuka's reputation as a daredevil performer.[32] [33] The leap, approximately 15 feet high, drew widespread acclaim for its risk and spectacle, though Snuka did not capture the title. By 1984, Snuka's rivalries expanded to include "Rowdy" Roddy Piper, sparked by Piper striking Snuka with a coconut on an episode of Piper's Pit, drawing significant heat for the villainous Piper. This angle positioned Snuka as a sympathetic hero amid WWF's growing national expansion. On February 18, 1985, at The War to Settle the Score, Snuka defeated Paul Orndorff in a singles match, further showcasing his main-event status. Snuka's peak culminated at the inaugural WrestleMania on March 31, 1985, at Madison Square Garden, where he served as the cornerman for Hulk Hogan and Mr. T in the main event tag match against Piper and Orndorff, with Cowboy Bob Orton in their corner.[34] His presence underscored his role as a top babyface supporting the promotion's flagship stars, though he did not compete. During this era, Snuka's popularity peaked as one of WWF's premier attractions, known for innovating high-risk maneuvers that influenced the industry's emphasis on athletic spectacle, despite never winning a major singles title. By mid-1985, Snuka departed WWF amid personal challenges, ending his initial run as a central figure in the promotion's early national boom.[2]International and Independent Stints (1985–1988)

Following his departure from the World Wrestling Federation in mid-1985, Snuka embarked on tours with New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW) in Japan. He participated in the IWGP & WWF Champion Series in May 1985, teaming with Mike Sharpe Jr. to defeat opponents on multiple dates, including victories on May 11 and subsequent events.[35] Later that year, on July 26, 1985, Snuka faced Kengo Kimura in a singles match taped for NJPW's World Pro Wrestling broadcast.[36] These appearances showcased Snuka's high-flying style to Japanese audiences, with NJPW engagements extending through December 1986.[1] In 1986, Snuka joined the American Wrestling Association (AWA), an independent promotion, where he engaged in several televised and house show matches. On July 12, 1986, he defeated Larry Zbyszko by disqualification in Milwaukee.[35] He also competed against Dennis Stamp in AWA Championship Wrestling that July and faced Jay York in Oakland, California, followed by a post-match interview highlighting his ongoing momentum.[37] [38] A prominent feud developed with Colonel DeBeers, culminating in matches such as an X on a pole bout on October 18, 1986, in Las Vegas, and interference incidents during encounters with Nick Bockwinkel.[39] [40] Snuka teamed with Greg Gagne against Buddy Rose and Doug Somers on September 20, 1986, and defeated Boris Zhukov on August 27, 1986, in Green Bay.[41] [35] These AWA bouts, often aired on ESPN, positioned Snuka as a fan favorite challenging established heels.[39] Snuka continued splitting time between AWA commitments and NJPW tours into 1987, maintaining his presence in independent circuits with sporadic matches against regional talent. By 1988, his activity tapered as he prepared for a WWF return, focusing on select independent appearances that reinforced his reputation for aerial maneuvers without major title pursuits.[1] Limited records indicate no championship wins during this period, emphasizing booking as a draw for high-spot exhibitions rather than storylines.[35]WWF Return and Decline (1989–1993)

Snuka returned to the World Wrestling Federation (WWF) in March 1989, following a period wrestling in regional promotions and Japan. His first match back occurred on March 7, 1989, at the El Paso Civic Center, where he defeated Boris Zhukov in a house show bout.[22] This appearance marked the beginning of vignettes promoting his comeback, building anticipation for his re-entry into the promotion.[2] At WrestleMania V on April 2, 1989, Snuka made his official in-ring return for the WWF, entering the 20-man battle royal but was eliminated early.[2] He followed with a television match on May 16, 1989, defeating Ted DiBiase via pinfall after DiBiase missed a clothesline.[2] This led to a brief feud with DiBiase, culminating at SummerSlam on August 28, 1989, where Snuka lost by countout due to interference from DiBiase's bodyguard Virgil.[42] His televised in-ring return came on the July 2, 1989, episode of WWF Wrestling Challenge, defeating jobber Tom Burton with his signature Superfly Splash.[43] However, by late 1989, Snuka transitioned into a jobber role, facing established heels to elevate rising stars; examples include losses to Dino Bravo in 1989 and jobbers like Bob Bradley.[44][45] This shift reflected his age—46 at the time—and the WWF's focus on younger talent like Mr. Perfect and the Ultimate Warrior, relegating veterans like Snuka to enhancement matches.[46] Appearances dwindled in 1990 and 1991, with sporadic house shows and television spots, such as a 1990 match against jobber Buddy Rose on WWF Prime Time Wrestling.[47] Snuka's final WWF match before a hiatus was a loss to Shawn Michaels on February 8, 1992, at the Los Angeles Sports Arena, after which he departed in March 1992 to pursue independent bookings.[48] Factors contributing to his exit included ongoing physical decline from years of high-impact wrestling and reported substance abuse issues that had previously affected his career.[13] Snuka made a one-off return on September 25, 1993, defeating Brian Christopher at a Madison Square Garden house show.[49] Two days later, on the September 27, 1993, episode of Monday Night Raw, he won against Paul Van Dale but was eliminated in a battle royal, signaling no sustained role amid the promotion's evolving roster.[50] This period encapsulated Snuka's decline from high-flying pioneer to nostalgic veteran, with limited impact due to age-related limitations and the WWF's emphasis on new eras.[2]ECW Championship Runs and Feuds (1992–1994)

Jimmy Snuka debuted in Eastern Championship Wrestling (ECW) on April 25, 1992, winning a battle royal to earn a spot in the tournament final for the newly established ECW Heavyweight Championship, which he captured that same night by defeating Salvatore Bellomo.[51] His inaugural reign lasted only one day, ending on April 26, 1992, when Johnny Hotbody defeated him for the title in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[52] Snuka regained the ECW Heavyweight Championship on July 12, 1992, in Philadelphia, marking his second reign with the title.[53] This period featured a renewed feud with Don Muraco, stemming from their earlier rivalry in the World Wrestling Federation during the early 1980s, where Muraco had held the Intercontinental Championship against Snuka in high-profile matches, including a steel cage bout at Madison Square Garden on October 17, 1983.[2] The ECW iteration of their conflict culminated on September 30, 1992, when Muraco defeated Snuka to claim the heavyweight title in Philadelphia.[54] Transitioning to the midcard, Snuka won the vacant ECW Television Championship on March 12, 1993, in Radnor, Pennsylvania, by defeating Glen Osbourne in a tournament final; this reign endured for 203 days.[55] During this time, Snuka engaged in various feuds, including defenses against challengers like Osbourne and building toward a loss to Terry Funk on October 1, 1993, in Philadelphia.[53] Into 1994, Snuka continued appearing in ECW events, participating in matches and angles that highlighted his veteran status amid the promotion's evolving hardcore style, though specific high-profile feuds tapered as younger talents rose.[2] His ECW tenure ended around mid-1994, after which he pursued opportunities elsewhere.[1]WCW and Sporadic Major Appearances (1993–2000)

Snuka made a one-off appearance for World Championship Wrestling (WCW) at Slamboree 1993: A Legends' Reunion on May 23, 1993, where he teamed with Don Muraco and Dick Murdoch in a six-man tag team match against Wahoo McDaniel, Blackjack Mulligan, and Jim Brunzell, which ended in a no-contest due to interference and brawling among the participants.[56] This event highlighted veteran wrestlers in a nostalgic format, aligning with WCW's occasional use of legends to draw crowds amid its competition with the WWF.[3] Following his departure from the WWF earlier in 1993, Snuka returned sporadically for the promotion, including a match on September 25, 1993, at Madison Square Garden where he defeated Brian Christopher by pinfall, and on the September 27, 1993, episode of WWF Monday Night Raw, where he pinned Paul Van Dale in a singles bout taped at the New Haven Coliseum.[57][58] These appearances were brief and did not lead to a full-time contract, reflecting Snuka's status as a part-time attraction leveraging his past fame while primarily working independent circuits and Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW).[3] In late 1996, Snuka participated in the WWF's Survivor Series on November 17 at the Madison Square Garden, competing in an elimination tag team match as part of a team with Yokozuna, Savio Vega, and Flash Funk against impostor versions of Diesel, Razor Ramon, Faarooq, and Vader; the bout ended in a double disqualification after excessive brawling.[59] This match featured storyline "fake" wrestlers mimicking WWF alumni who had jumped to WCW, positioning Snuka as a loyal veteran in the ongoing Monday Night Wars narrative. Such sporadic WWF engagements underscored his enduring name recognition despite diminished in-ring role due to age and prior injuries. Snuka's final notable WCW involvement came on the January 10, 2000, episode of WCW Monday Nitro, where the 56-year-old wrestler defeated Jeff Jarrett in a steel cage match by pinfall after executing his signature Superfly Splash from the top of the cage onto the prone champion.[60] The high-risk maneuver, a nod to Snuka's pioneering aerial style, reportedly contributed to Jarrett sustaining a concussion, highlighting the physical toll on aging performers in WCW's chaotic booking environment during its decline.[61] These isolated major promotion outings from 1993 to 2000 were interspersed with extensive independent work, marking a transition toward semi-retirement while capitalizing on legacy appeal.[3]Later Independent Work and Retirement (1995–2015)

Following his departures from major promotions, Snuka made sporadic appearances on the independent circuit throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, often in nostalgia matches or short feuds at regional events. One notable bout occurred on August 15, 1997, at the IWA Night of the Legends in Kannapolis, North Carolina, where Snuka defeated The Masked Superstar by disqualification after interference from his manager Afa.[4] He also engaged in a prolonged series against The Metal Maniac across various promotions, defeating him on dates including March 1, 1997, at Maccabiah Mania II in Pennsylvania, and January 29, 2004, in a WPCW event in Hawaii.[62] Snuka won the majority of these encounters, leveraging his experience in high-impact spots despite visible physical decline.[3] Into the mid-2000s, Snuka competed internationally and domestically in smaller promotions, such as a July 1, 2006, tag team victory over Jay Phoenix and Stevie Lynn alongside Darren Burridge for 1PW in the United Kingdom, and a win by disqualification against Greg Valentine on March 5, 2006, at World Wrestling Legends 6:05 - The Reunion.[35] Stateside, he secured a victory over Salvatore Sincere on October 6, 2006, for WSU/NWS during the Women's J-Cup Tournament.[35] These outings typically featured multi-man tags or singles against midcard talent, emphasizing Snuka's legacy rather than athletic peaks, with outcomes favoring him in most documented cases.[62] By the late 2000s and early 2010s, Snuka's independent schedule shifted toward family-involved or local fairground events in promotions like Top Rope Promotions (TRP), Big Time Wrestling (BTW), and UCW-Zero. On July 31, 2011, he defeated Gregory Edwards in a TRP singles match at the Elks Lodge in Pennsylvania.[62] In 2013, he teamed with Balls Mahoney for a hardcore win over Jeff Noyze and Vinny Cenzo in FWF, and with Gary Eleniefsky and Shane Alden to defeat The Wingmen and Brickhouse Baker at the Rochester Country Fair for TRP.[62] A 2014 UCW-Zero tag match saw him join son Deuce Snuka and Tom Howard in defeating The Foundation (Derrick Jannetty, Martin Casaus, and Stevie Slick).[62] His final documented independent bout was on August 8, 2014, teaming with The Patriot to beat Brodie Williams and Mr. TA at the Montgomery County Agricultural Fair for BTW.[62] Snuka's in-ring activity tapered off after 2014 amid accumulating health complications from decades of ring trauma, culminating in an August 2015 stomach cancer diagnosis that precluded further competition.[63] These later years marked a semi-retirement phase focused on occasional guest spots rather than full tours, reflecting physical limitations while capitalizing on his enduring draw as a high-flying pioneer.[64]Post-Retirement WWE Engagements (1996–2009)

Following his induction into the WWF Hall of Fame on November 16, 1996, Snuka made sporadic in-ring appearances for the promotion, leveraging his legacy as a high-flying pioneer to contribute to special events.[13] The ceremony, held as part of the buildup to Survivor Series, honored Snuka alongside inductees such as Captain Lou Albano and Killer Kowalski, recognizing his contributions to the WWF's early 1980s product, including his iconic steel cage leap against Don Muraco at Madison Square Garden in 1983.[65] Snuka's most notable post-induction match occurred at Survivor Series on November 17, 1996, where he debuted as the surprise partner for Flash Funk, Savio Vega, and Yokozuna in a 4-on-4 elimination bout against Faarooq, Vader, Razor Ramon II, and Diesel II (portrayed by imposters). The match, managed by Jim Cornette for the heels, ended in a no-contest after interference escalated into chaos, with Snuka eliminating Razor Ramon II via pinfall before the bout dissolved. This appearance, lasting approximately 9 minutes and 48 seconds, marked Snuka's return to WWF television programming after a period focused on independent circuits and ECW affiliations.[66] Throughout the early 2000s, Snuka's WWE engagements remained limited to occasional non-competitive roles and nostalgia segments, reflecting his semi-retired status amid ongoing independent bookings. He received a lifetime achievement award from WWE at Madison Square Garden, underscoring his enduring appeal to fans despite diminished physical capacity.[35] Snuka's final significant WWE in-ring appearance during this period came at WrestleMania 25 on April 5, 2009, in Houston, Texas, where he teamed with fellow Hall of Famers Ricky Steamboat and Roddy Piper against Chris Jericho in a "Legends of WrestleMania" match. The trio, representing iconic figures from WWE's formative eras, lost via pinfall after Jericho capitalized on the veterans' age-related limitations, with Snuka pinned following a Codebreaker. This bout, part of a broader "Hall of Fame Legends" showcase, highlighted Snuka's role in bridging WWE's past and present, though his participation was brief and symbolic given his advanced age of 65.[35] These engagements affirmed Snuka's status as a ceremonial figurehead, with no full-time contract or storyline arcs, as WWE prioritized younger talent during the PG era transition.Wrestling Style and Innovations

Signature Moves and High-Flying Pioneering

Jimmy Snuka's primary finishing move was the Superfly Splash, a high-impact diving splash executed from the top rope onto an opponent lying prone in the ring.[67] This maneuver, which Snuka performed with exceptional elevation and body control, became synonymous with his "Superfly" persona and was first prominently featured in his matches during the late 1970s in promotions like Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling, with documented uses as early as March 21, 1979.[68] Among his signature moves, Snuka also employed the diving crossbody and diving headbutt, which complemented his aerial arsenal by emphasizing speed and precision over brute force.[69] Snuka pioneered the integration of high-flying techniques into mainstream North American professional wrestling, particularly during his World Wrestling Federation tenure from 1982 onward, where his athleticism drawn from Fijian heritage and prior territorial experience elevated the style beyond sporadic use in smaller promotions.[70] His most emblematic innovation occurred on October 17, 1983, in a steel cage match against Intercontinental Champion Don Muraco at Madison Square Garden, when Snuka executed a Superfly Splash from the top of the 15-foot cage structure onto Muraco below, marking one of the earliest televised instances of such extreme aerial risk in a major promotion and captivating audiences with its raw physicality.[33] This feat, repeated in variations throughout his career up to 1993, demonstrated causal links between wrestler physiology, ring apparatus, and crowd engagement, as Snuka's willingness to perform unprotected dives from heights increased match spectacle and injury potential, influencing safety protocols in later eras.[71] Regarded by wrestling historians as a foundational figure in aerial offense, Snuka's techniques—emphasizing leaps from turnbuckles and barriers—bridged territorial-era athleticism with the high-spot era, directly enabling subsequent wrestlers to adopt and refine similar maneuvers without the era's prior constraints on perceived realism.[69] His innovations prioritized empirical execution over scripted caution, as evidenced by the move's consistent deployment across decades despite documented physical tolls, establishing a template for high-flying as a viable competitive edge in heavyweight divisions.[70]Influence on Subsequent Wrestlers

Snuka's introduction of high-flying techniques to mainstream American wrestling, particularly through his signature Superfly Splash—a frog splash executed from the top rope—marked a shift toward aerial innovation in an industry previously focused on ground-based power moves. This style, debuting prominently in the World Wrestling Federation during the early 1980s, emphasized athleticism and spectacle, influencing the evolution of match dynamics by encouraging performers to incorporate elevated risks for crowd engagement.[67][72] A defining moment occurred on October 17, 1983, when Snuka climbed the steel cage and dove headfirst onto Don Muraco at Madison Square Garden, an unprecedented feat that captivated audiences and directly inspired future wrestlers. Mick Foley, then a teenager in attendance, cited this dive as the catalyst for his decision to pursue professional wrestling, later describing Snuka's performance as the event that "lit the fire" for his career despite the physical toll it foreshadowed. Foley has named Snuka his primary inspiration among all wrestlers, crediting the Fijian's fearlessness for shaping his own high-risk approach, including multiple cage-related stunts.[73][5] Snuka's legacy extended to broader adoption of top-rope dives and splashes, which became staples for subsequent high-flyers seeking to replicate his crowd-popping athleticism. His pioneering aerial offense contributed to a generational shift, where wrestlers emulated the blend of power and elevation to differentiate from traditional brawlers, though it also amplified injury risks in an unregulated era. This influence persisted into the 1990s and beyond, as Snuka's techniques informed the repertoires of performers prioritizing spectacle over sustainability.[74][72]Personal Life

Family and Descendants in Wrestling

Jimmy Snuka had several children, two of whom pursued careers in professional wrestling: his daughter Sarona Snuka, professionally known as Tamina, and his son James Reiher Jr., who competed under names including Deuce and Sim Snuka.[75][76] Sarona Snuka, born May 10, 1978, debuted in WWE in 2010 as Tamina, initially aligning with the Legacy stable before competing in the women's division, where she held the WWE Women's Tag Team Championship once in 2021 alongside Natalya.[75] Her ring style incorporated power moves echoing her father's high-flying legacy, though adapted to her larger frame at 5 feet 9 inches and over 200 pounds, and she remained active on WWE's roster into 2025, often in midcard roles.[77] James Reiher Jr., born August 18, 1983, began wrestling independently in the late 1990s before signing with WWE in 2007, debuting as Deuce in the throwback greaser tag team Deuce 'n Domino, managed by Cherry; the duo feuded with teams like Cryme Tyme but never captured titles during their 2007–2008 run on SmackDown.[78] Repackaged in 2012 as Sim Snuka to highlight his lineage, he competed in short matches against stars like The Miz and Ryback, losing via countout or submission, before his WWE release in May 2013; he continued on the independent circuit until retiring around 2014.[79][80] Snuka's wrestling family ties extended loosely to the Anoa'i dynasty through his 1964 marriage to Sharon Ili, daughter of Reverend Amituana'i Anoa'i, making Tamina and Deuce first cousins once removed to figures like Dwayne Johnson, though Snuka himself was of Fijian descent and not a blood relative.[12] No further descendants, such as grandchildren, have entered professional wrestling as of 2025.[81]Lifestyle, Substance Issues, and Relationships

Snuka maintained a lifestyle characteristic of many professional wrestlers during the 1970s and 1980s, involving extensive travel, physical demands, and off-ring socializing that often included heavy partying and substance use.[74] His ex-wife, Sharon Georgi, testified in court proceedings about his frequent alcohol consumption, cocaine use, and steroid intake, which contributed to erratic behavior and health deterioration over time.[82] Psychological evaluations during legal matters further confirmed a long-term pattern of alcohol and cocaine abuse, alongside tobacco smoking and heavy drinking, exacerbating cognitive impairments from wrestling injuries.[83][84] In relationships, Snuka was married to Sharon Snuka (née Georgi or Ili), with whom he had two daughters, though the union involved reported physical abuse; Georgi stated that Snuka hospitalized her five months after their marriage through repeated assaults.[5] He maintained a concurrent romantic involvement with Nancy Argentino in 1983, while still wed to Sharon, reflecting overlapping personal commitments common in his era's wrestling circuit.[85] Posthumously revealed details indicated a secret decade-long marriage to Patrice Aguirre, mother of wrestler Gino Hernandez, undisclosed during his lifetime and complicating public understanding of his familial dynamics.[86] These relationships were strained by Snuka's substance issues and the transient nature of his profession, contributing to instability in his personal affairs.[87]Health Decline

Long-Term Injuries from Wrestling