Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

LIO (SCSI target)

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| LIO Target | |

|---|---|

LIO Linux SCSI Target | |

| Original authors | Nicholas Bellinger Jerome Martin |

| Developers | Datera, Inc. |

| Initial release | January 14, 2011 |

| Repository | github |

| Written in | C, Python |

| Operating system | Linux |

| Type | Block storage |

| License | GNU General Public License |

| Website | linux-iscsi.org at the Wayback Machine (archived 2022-10-06) |

The Linux-IO (LIO) is an open-source Small Computer System Interface (SCSI) target implementation included with the Linux kernel.[1][better source needed]

Unlike initiators, which begin sessions, LIO functions as a target, presenting one or more Logical Unit Numbers (LUNs) to a SCSI initiator, receiving SCSI commands, and managing the input/output data transfers.[citation needed]

LIO supports a wide range of storage protocols and transport fabrics, including but not limited to Fibre Channel over Ethernet (FCoE), Fibre Channel, IEEE 1394 and iSCSI.[citation needed]

It is utilized in several Linux distributions and is a popular choice for cloud environments due to its integration with tools like QEMU/KVM, libvirt, and OpenStack.[citation needed]

The LIO project is maintained by Datera,[dubious – discuss] a Silicon Valley-based storage solutions provider. On January 15, 2011, LIO was merged into the Linux kernel mainline with version 2.6.38, which was officially released on March 14, 2011.[2][3] Subsequent versions of the Linux kernel have introduced additional fabric modules to expand its compatibility.[citation needed]

LIO competes with other SCSI target modules in the Linux ecosystem. The SCSI Target Framework (SCST)[4] is a prominent alternative for general SCSI target functionality, while for iSCSI-specific targets, the older iSCSI Enterprise Target (IET) and SCSI Target Framework (STGT) also have industry adoption.[5][6]

Background

[edit]The SCSI standard provides an extensible semantic abstraction for computer data storage devices, and is used with data storage systems. The SCSI T10 standards[7] define the commands[8] and protocols of the SCSI command processor (sent in SCSI CDBs), and the electrical and optical interfaces for various implementations.

A SCSI initiator is an endpoint that initiates a SCSI session. A SCSI target is the endpoint that waits for initiator commands and executes the required I/O data transfers. The SCSI target usually exports one or more LUNs for initiators to operate on.

The LIO Linux SCSI Target implements a generic SCSI target that provides remote access to most data storage device types over all prevalent storage fabrics and protocols. LIO neither directly accesses data nor does it directly communicate with applications.

Architecture

[edit]

LIO implements a modular and extensible architecture around a parallelised SCSI command processing engine.[9]

The LIO SCSI target engine is independent of specific fabric modules or backstore types. Thus, LIO supports mixing and matching any number of fabrics and backstores at the same time. The LIO SCSI target engine implements a comprehensive SPC-3/SPC-4[10] feature set with support for high-end features, including SCSI-3/SCSI-4 Persistent Reservations (PRs), SCSI-4 Asymmetric Logical Unit Assignment (ALUA), VMware vSphere APIs for Array Integration (VAAI),[11] T10 DIF, etc.

LIO is configurable via a configfs-based[12] kernel API, and can be managed via a command-line interface and API (targetcli).

SCSI target

[edit]The concept of a SCSI target isn't restricted to physical devices on a SCSI bus, but instead provides a generalised model for all receivers on a logical SCSI fabric. This includes SCSI sessions across interconnects with no physical SCSI bus at all. Conceptually, the SCSI target provides a generic block storage service or server in this scenario.

Back-stores

[edit]Back-stores provide the SCSI target with generalised access to data storage devices by importing them via corresponding device drivers. Back-stores do not need to be physical SCSI devices.

The most important back-store media types are:

- Block: The block driver allows using raw Linux block devices as back-stores for export via LIO. This includes physical devices, such as HDDs, SSDs, CDs/DVDs, RAM disks, etc., and logical devices, such as software or hardware RAID volumes or LVM volumes.

- File: The file driver allows using files that can reside in any Linux file system or clustered file system as back-stores for export via LIO.

- Raw: The raw driver allows using unstructured memory as back-stores for export via LIO.

As a result, LIO provides a generalised model to export block storage.

Fabric modules

[edit]Fabric modules implement the front-end of the SCSI target by encapsulating and abstracting the properties of the various supported interconnect. The following fabric modules are available.

FCoE

[edit]

The Fibre Channel over Ethernet (FCoE) fabric module allows the transport of Fibre Channel protocol (FCP) traffic across lossless Ethernet networks. The specification, supported by a large number of network and storage vendors, is part of the Technical Committee T11 FC-BB-5 standard.[13]

LIO supports all standard Ethernet NICs.

The FCoE fabric module was contributed by Cisco and Intel, and released with Linux 3.0 on July 21, 2011.[14]

Fibre Channel

[edit]Fibre Channel is a high-speed network technology primarily used for storage networking. It is standardized in the Technical Committee T11[15] of the InterNational Committee for Information Technology Standards (INCITS).

The QLogic Fibre Channel fabric module supports 4- and 8-gigabit speeds with the following HBAs:

- QLogic 2400 Series (QLx246x), 4GFC

- QLogic 2500 Series (QLE256x), 8GFC (fully qual'd)

The Fibre Channel fabric module[16] and low-level driver[17] (LLD) were released with Linux 3.5 on July 21, 2012.[18]

With Linux 3.9, the following QLogic HBAs and CNAs are also supported:

- QLogic 2600 Series (QLE266x), 16GFC, SR-IOV

- QLogic 8300 Series (QLE834x), 16GFS/10 GbE, PCIe Gen3 SR-IOV

- QLogic 8100 Series (QLE81xx), 8GFC/10 GbE, PCIe Gen2

This makes LIO the first open source target to support 16-gigabit Fibre Channel.

IEEE 1394

[edit]

The FireWire SBP-2 fabric module enables Linux to export local storage devices via IEEE 1394, so that other systems can mount them as an ordinary IEEE 1394 storage device.

IEEE 1394 is a serial-bus interface standard for high-speed communications and isochronous real-time data transfer. It was developed by Apple as "FireWire" in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and Macintosh computers have supported "FireWire target disk mode" since 1999.[19]

The FireWire SBP-2 fabric module was released with Linux 3.5 on July 21, 2012.[18][20]

iSCSI

[edit]The Internet Small Computer System Interface (iSCSI) fabric module allows the transport of SCSI traffic across standard IP networks.

By carrying SCSI sessions across IP networks, iSCSI is used to facilitate data transfers over intranets and manage storage over long distances. iSCSI can be used to transmit data over local area networks (LANs), wide area networks (WANs), or the Internet, and can enable location-independent and location-transparent data storage and retrieval.

The LIO iSCSI fabric module also implements a number of advanced iSCSI features that increase performance and resiliency, such as Multiple Connections per Session (MC/S) and Error Recovery Levels 0-2 (ERL=0,1,2).

LIO supports all standard Ethernet NICs.

The iSCSI fabric module was released with Linux 3.1 on October 24, 2011.[21]

iSER

[edit]Networks supporting remote direct memory access (RDMA) can use the iSCSI Extensions for RDMA (iSER) fabric module to transport iSCSI traffic. iSER permits data to be transferred directly into and out of remote SCSI computer memory buffers without intermediate data copies (direct data placement or DDP) by using RDMA.[22] RDMA is supported on InfiniBand networks, on Ethernet with data center bridging (DCB) networks via RDMA over Converged Ethernet (RoCE), and on standard Ethernet networks with iWARP enhanced TCP offload engine controllers.

The iSER fabric module was developed together by Datera and Mellanox Technologies, and first released with Linux 3.10 on June 30, 2013.[23]

SRP

[edit]The SCSI RDMA Protocol (SRP) fabric module allows the transport of SCSI traffic across RDMA (see above) networks. As of 2013, SRP was more widely used than iSER, although it is more limited, as SCSI is only a peer-to-peer protocol, whereas iSCSI is fully routable. The SRP fabric module supports the following Mellanox host channel adapters (HCAs):

- Mellanox ConnectX-2 VPI PCIe Gen2 HCAs (x8 lanes), single/dual-port QDR 40 Gbit/s

- Mellanox ConnectX-3 VPI PCIe Gen3 HCAs (x8 lanes), single/dual-port FDR 56 Gbit/s

- Mellanox ConnectX-IB PCIe Gen3 HCAs (x16 lanes), single/dual-port FDR 56 Gbit/s

The SRP fabric module was released with Linux 3.3 on March 18, 2012.[24]

In 2012, c't magazine measured almost 5000 MB/s throughput with LIO SRP Target over one Mellanox ConnectX-3 port in 56 Gbit/s FDR mode on a Sandy Bridge PCI Express 3.0 system with four Fusion-IO ioDrive PCI Express flash memory cards.

USB

[edit]The USB Gadget fabric module enables Linux to export local storage devices via the Universal Serial Bus (USB), so that other systems can mount them as an ordinary storage device.

USB was designed in the mid-1990s to standardize the connection of computer peripherals, and has also become common for data storage devices.

The USB Gadget fabric module was released with Linux 3.5 on July 21, 2012.[25]

Targetcli

[edit]targetcli is a user space single-node management command line interface (CLI) for LIO.[26] It supports all fabric modules and is based on a modular, extensible architecture, with plug-in modules for additional fabric modules or functionality.

targetcli provides a CLI that uses an underlying generic target library through a well-defined API. Thus the CLI can easily be replaced or complemented by a UI with other metaphors, such as a GUI.

targetcli is implemented in Python and consists of three main modules:

- the underlying rtslib and API.[27]

- the configshell, which encapsulates the fabric-specific attributes in corresponding 'spec' files.

- the targetcli shell itself.

Detailed instructions on how to set up LIO targets can be found on the LIO wiki.[26]

Linux distributions

[edit]targetcli and LIO are included in most Linux distributions per default. Here is an overview of the most popular ones, together with the initial inclusion dates:

| Distribution | Version[a] | Release | Archive | Installation | Source git | Documentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpine Linux | 2.5 | 2011-11-07 | Alpine Linux mirror Archived 2012-12-12 at the Wayback Machine | apk add targetcli-fb

|

targetcli-fb.git | How-to |

| CentOS | 6.2 | 2011-12-20 | CentOS mirror | su -c 'yum install fcoe-target-utils'

|

targetcli-fb.git | Tech Notes |

| Debian | 7.0 ("wheezy") | 2013-05-04 | Debian pool | su -c 'apt-get install targetcli'

|

targetcli.git | Debian - LIO Wiki at the Wayback Machine (archived 2022-08-20) |

| Fedora | 16 | 2011-11-08 | Fedora Rawhide | su -c 'yum install targetcli'

|

targetcli-fb.git | Target Wiki |

| openSUSE | 12.1 | 2011-11-08 | Requires manual installation from Datera targetcli.git repos. | |||

| RHEL[b] | 6.2 | 2011-11-16 | Fedora Rawhide | su -c 'yum install fcoe-target-utils'

|

targetcli-fb.git | Tech Notes |

| Scientific Linux | 6.2 | 2012-02-16 | SL Mirror | su -c 'yum install fcoe-target-utils'

|

targetcli-fb.git | Tech Notes |

| SLES | 11 SP3 MR | 2013-12 | - | su -c 'zypper in targetcli'

|

targetcli.git | SLES - LIO Wiki at the Wayback Machine (archived 2022-08-02) |

| Ubuntu | 12.04 LTS (precise) | 2012-04-26 | Ubuntu universe | sudo apt-get install targetcli

|

targetcli.git | Ubuntu - LIO Wiki at the Wayback Machine (archived 2022-10-21) |

See also

[edit]- The SCST Linux SCSI target software stack

- Fibre Channel

- Fibre Channel over Ethernet (FCoE)

- IEEE 1394 / Firewire

- InfiniBand

- iSCSI

- iSCSI Extensions for RDMA (iSER)

- SCSI RDMA Protocol (SRP)

- USB

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "LIO". Linux-IO, the Linux SCSI Target wiki. 2016-03-12. Archived from the original on 2022-08-20.

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2011-01-14). "Trivial merge". Kernel.org. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Thorsten Leemhuis (2011-03-02). "Kernel Log: Coming in 2.6.38 (Part 4) - Storage". Heise Online.

- ^ "A tale of two SCSI targets". Lwn.net. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- ^ Haas, Florian (May 2012). "Replicate Everything! Highly Available iSCSI Storage with DRBD and Pacemaker". Linux Journal. Archived from the original on 2014-01-20. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Bolkhovitin, Vladislav (2018-04-11). "SCST vs STGT". Generic SCSI Target Subsystem for Linux. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Technical Committee T10. "SCSI Storage Interfaces". t10.org. Retrieved 2012-12-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ SCSI Commands Reference Manual (PDF). 100293068, Rev. C. Scotts Valley: Seagate Technology. April 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-31. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ Bellinger, Nicholas (2009). Current Status and Future of iSCSI on the Linux platform (PDF). Linux Plumbers Conference.

- ^ Ralph Weber (2011-01-17). "SCSI Primary Commands - 4 (SPC-4)". t10.org. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ^ "vStorage APIs for Array Integration". Linux-IO, the Linux SCSI Target wiki. 2015-08-07. Archived from the original on 2022-08-20.

- ^ Jonathan Corbet (2005-08-24). "Configfs - an introduction". lwn.net. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ^ "Fibre Channel: Backbone - 5 revision 2.00" (PDF). American National Standard for Information Technology International Committee for Information Technology Standards Technical Group T11. June 4, 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2011-04-18). "[SCSI] tcm_fc: Adding FC_FC4 provider (tcm_fc) for FCoE target (TCM - target core) support". Kernel.org. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ "T11 Home Page". t11.org. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2012-05-15). "[SCSI] tcm_qla2xxx: Add >= 24xx series fabric module for target-core". Kernel.org. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2012-05-15). "[SCSI] qla2xxx: Add LLD target-mode infrastructure for >= 24xx series". Kernel.org. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ a b Thorsten Leemhuis (2012-07-03). "Kernel Log: Coming in 3.5 (Part 2) - Filesystems and storage". Heise Online. Retrieved 2013-01-14.

- ^ "How to use and troubleshoot FireWire target disk mode". apple.com. Retrieved 2012-12-24.

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2012-04-15). "sbp-target: Initial merge of firewire/ieee-1394 target mode support". Kernel.org. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2011-07-27). "iSCSI merge". Kernel.org. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ RFC 5041

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2013-04-30). "Merge branch 'for-next-merge'". Kernel.org. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2012-01-18). "InfiniBand/SRP merge". Kernel.org. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ "Merge branch 'usb-target-merge'". Kernel.org. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ a b "Targetcli". Linux-IO, the Linux SCSI Target wiki. 2012-12-09. Archived from the original on 2013-03-02. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ Jerome Martin (2011-08-03). "Package rtslib". daterainc.com. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ "Chapter 6. Storage". Access.redhat.com. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

External links

[edit]- Official website at the Wayback Machine (archived 2022-10-13)

- Datera website

LIO (SCSI target)

View on GrokipediaOverview and History

Definition and Purpose

LIO, also known as Linux-IO Target, is an open-source SCSI target framework integrated into the mainline Linux kernel since version 2.6.38, released in March 2011.[8][7] It serves as a unified subsystem that replaced earlier out-of-tree implementations like the SCSI Target Subsystem (STGT), providing a standardized, in-kernel mechanism for Linux systems to emulate SCSI target devices.[4][9] The primary purpose of LIO is to enable Linux-based servers to export local block storage resources—such as files, block devices, or RAM disks—over network fabrics to remote SCSI initiators, effectively turning commodity hardware into shared storage appliances.[4][10] This capability supports protocols like iSCSI without relying on proprietary hardware accelerators, allowing initiators to access the storage as standard SCSI logical units (LUNs) for applications requiring persistent, high-availability data access.[7][11] Key benefits of LIO stem from its fully in-kernel design, which minimizes latency by processing SCSI commands directly within the kernel space, avoiding the overhead of userspace mediation found in alternatives.[10] Its modular architecture further enhances flexibility, supporting pluggable backstore components for diverse storage backends and fabric modules for multiple network protocols, thereby facilitating enterprise-grade storage virtualization and scalability in data center environments.[12][13] The development of LIO reflects the broader evolution of SCSI target support in Linux during the post-2000s era, when surging demands for cost-effective storage area networks (SANs) and IP-based storage solutions outpaced the capabilities of fragmented, userspace-driven subsystems.[4] This shift necessitated a cohesive, kernel-integrated framework to deliver reliable performance for emerging enterprise workloads, such as virtualized storage pooling and remote block access in clustered systems.[8][14]Development Timeline

The development of LIO began in 2009 under the leadership of Nicholas A. Bellinger from the Linux-iSCSI.org project, aiming to create a modular, high-performance SCSI target framework for the Linux kernel, building on prior iSCSI target efforts like LIOTarget v2.9.[15] Initial contributions came from the broader Linux/SCSI community, including developers from Linbit and Neterion, focusing on generic target engine capabilities.[15] By late 2010, following community discussions comparing LIO with alternatives like SCST, LIO was selected as the primary in-kernel SCSI target to replace the aging STGT framework, addressing needs for better performance and broader protocol support.[4] The core LIO patches, authored primarily by Bellinger, were merged into the Linux kernel mainline with version 2.6.38, released on March 14, 2011.[16] Key milestones followed rapidly: FCoE support via the Open-FCoE target fabric module was announced in December 2010 and integrated into kernel 3.0, released in July 2011, enabling SCSI over Ethernet with contributions from hardware vendors.[17] The full iSCSI target fabric became operational in kernel 3.1 later that year.[18] In 2013, iSER support—allowing iSCSI over RDMA—was added in kernel 3.10 through collaboration with Mellanox Technologies, enhancing low-latency storage access.[19] Bellinger has remained the primary maintainer, with significant input from organizations like Red Hat (e.g., Andy Grover on iSCSI enhancements) and SUSE, alongside hardware vendors for protocol extensions such as SRP and Fibre Channel.[20] LIO's modular architecture has facilitated ongoing evolution, with brief references to its extensibility for new protocols in core documentation. Maintenance has continued through the kernel 5.x and 6.x series into 2025, incorporating performance optimizations, SCSI feature additions like T10-DIF for data integrity, and security fixes—such as CVE-2020-28374, which resolved directory traversal vulnerabilities in target_core_xcopy prior to kernel 5.10.7.[21] As of kernel 6.6 and later, LIO remains the standard in-kernel SCSI target, supporting diverse storage fabrics.[1]Core Architecture

SCSI Target Engine

The SCSI Target Engine in LIO, implemented primarily through thetarget_core_mod kernel module, serves as the central component responsible for handling SCSI command processing and maintaining state for target operations across various storage fabrics. This module provides a fabric-independent abstraction layer that processes incoming SCSI commands from initiators, manages logical unit numbers (LUNs), and oversees command queuing to ensure efficient I/O handling in a multi-initiator environment. By operating entirely within the Linux kernel, it eliminates userspace overhead, enabling high-performance storage virtualization that supports standards-compliant SCSI interactions without protocol-specific dependencies.[22]

Key mechanisms within the engine include SCSI command parsing, which involves decoding Command Descriptor Blocks (CDBs) and initializing command structures for execution, and robust error handling that responds to failures such as resource unavailability or invalid requests by returning appropriate SCSI status codes like BUSY or CHECK CONDITION. Task management functions are integral, supporting operations defined in the SCSI Architecture Model (SAM), such as ABORT_TASK to terminate a specific command and LUN_RESET to reinitialize a logical unit, ensuring reliable recovery in multipath and clustered setups. These functions process Task Management Requests (TMRs) to maintain session integrity and handle exceptions like command timeouts or transport errors, abstracting the complexities of SCSI-3 standards—including task attributes (e.g., SIMPLE, ORDERED, HEAD_OF_QUEUE) and persistence requirements—into a unified interface for upper-layer fabric modules.[22]

Internal data structures facilitate tracking of initiator-target interactions, with se_session representing an active connection between an initiator and the target, encapsulating session parameters like authentication state, maximum connections, and tag allocation for command ordering. Each se_session manages multiple commands via se_cmd structures, which store CDB details, data buffers, and execution context, while se_tmr (struct se_tmr_req) specifically handles TMRs by linking to reference commands or LUNs for targeted operations like resets or aborts. These structures collectively abstract SCSI-3 semantics, such as LUN mapping and reservation handling under SPC-4 (SCSI Primary Commands-4), allowing the engine to enforce queue algorithms (e.g., restricted reordering) and maintain device server state across fabric handoffs.[22]

Performance is optimized through an in-kernel threading model that leverages Linux workqueues and kthreads to process I/O asynchronously, dispatching commands to backstores for data movement while keeping CPU utilization low even under high loads. Queue depth management occurs at the session level, where each se_session allocates a pool of command tags (via transport_alloc_session_tags) to limit concurrent operations per initiator, preventing overload and enabling dynamic adjustment based on fabric capabilities—typically supporting depths from tens to thousands of commands to achieve line-rate throughput on modern hardware. This design ensures scalability for enterprise scenarios, such as supporting thousands of LUNs per target without introducing latency from context switches.[22]

Backstore Components

In LIO, the SCSI target subsystem for the Linux kernel, backstores serve as pluggable storage providers that abstract the underlying data storage for Logical Unit Numbers (LUNs) exported by the target. These components allow the target engine to access local storage resources without direct dependency on specific hardware or filesystem implementations, enabling flexible mapping of virtual SCSI devices to physical or virtual storage.[12] LIO supports four primary backstore types: fileio, which uses regular files on a filesystem; block, which utilizes block devices such as hard disks or SSDs; pscsi, which provides pass-through access to local SCSI devices; and ramdisk, which allocates volatile memory for temporary storage. The fileio backstore is particularly versatile for development and testing, as it operates on files that can be created using standard tools like dd to simulate disk images. The block backstore is preferred for production environments sharing block-level devices, while pscsi enables direct exposure of existing SCSI hardware, and ramdisk offers high-speed but non-persistent storage.[12][23][24] Backstores map LUNs to physical storage through the LIO configfs interface, where a storage object is first created and enabled under /sys/kernel/config/target/core, then linked to a LUN within a target portal group. For instance, to create a fileio backstore from a disk image, a file of desired size is generated (e.g., using dd if=/dev/zero of=image.img bs=1M count=10240 for a 10 GB sparse file), followed by configuring the backstore with the file path and size via echo commands to set attributes like fd_dev_name and fd_dev_size, and enabling it with echo 1 > enable. This mapping allows the target engine to translate SCSI I/O commands into corresponding operations on the backing storage, such as read/write requests to the file or device, ensuring data integrity through the kernel's block layer.[25][12] Advanced features in LIO backstores include support for thin provisioning, primarily in the fileio type, where LUNs can be allocated larger virtual sizes than the actual underlying file using sparse allocation to optimize space usage. Write-back caching is emulatable, particularly in fileio and block backstores, allowing asynchronous writes to improve performance by buffering data before committing to storage (configurable via emulate_write_cache attribute). Integration with filesystems like ext4 or XFS is inherent to fileio backstores, enabling virtual block devices on mounted volumes for scenarios requiring filesystem-level management without direct hardware access.[26][25][23] Limitations of LIO backstores stem from their SCSI-centric design, with no native support for NVMe protocols; instead, NVMe devices must be exposed through the kernel's block layer as standard block devices for use with the block backstore. All I/O submission relies on the generic block layer, which may introduce overhead compared to direct hardware access in non-SCSI storage stacks.[24][12]Fabric Modules Overview

Fabric modules in LIO serve as protocol adapters that enable the SCSI target engine to interface with diverse network fabrics, allowing the core engine to remain protocol-agnostic while supporting multiple transport layers. For instance, the iSCSI fabric module, implemented as theiscsi_target_mod kernel module, handles iSCSI-specific operations such as session establishment and command encapsulation. These modules register with the target engine through the target_core_register_fabric API, which integrates the fabric into the LIO framework via ConfigFS hierarchies, typically under /sys/kernel/config/target/<fabric_name>. This registration process ensures that fabric-specific logic is isolated, permitting the core to process SCSI commands uniformly across adapters.

The modular design of LIO fabric modules emphasizes hot-pluggability through Linux kernel modules, enabling dynamic loading and unloading without rebooting the system. Developers can create and maintain fabric modules independently, compiling them as loadable kernel modules (.ko files) that leverage the struct target_core_fabric_ops skeleton for essential callbacks like command reception and response handling. This approach facilitates rapid iteration and integration of new protocols, as seen in the use of tools like the TCM v4 fabric module script generator, which automates the creation of boilerplate code for custom adapters. By abstracting fabric-specific details, LIO allows administrators to mix fabrics on a single system, enhancing flexibility in storage deployments.[27]

Common interfaces provided by fabric modules abstract key operations such as portal group management, endpoint configuration, and authentication handshakes from the core engine. Portal groups, analogous to iSCSI Target Portal Groups (TPGs), define listening endpoints (e.g., IP addresses and ports) via ConfigFS entries like tpgt_1 under a target's IQN, enabling multi-port configurations for high availability. Endpoint management involves creating and linking network interfaces or device paths to these groups, while authentication—such as CHAP for iSCSI—is handled at the fabric level through dedicated ConfigFS attributes like discovery_auth, ensuring secure initiator connections without core modifications. These abstractions maintain consistency across fabrics, simplifying management via tools like targetcli.[27][28]

LIO's fabric modules originated with the framework's integration into the Linux kernel in version 2.6.38 in March 2011, initially supporting basic fabrics like loopback and iSCSI (added in 3.1 later that year). Subsequent expansions included the SRP fabric in kernel 3.3 (March 2012) for RDMA networks and the USB gadget fabric in 3.5 (July 2012), with FireWire (IEEE 1394) support via SBP-2 in 3.4 (May 2012); iSER for RDMA-enhanced iSCSI followed in 3.10 (June 2013).[29][30] By 2015, these modules had matured with improved performance and compatibility features, and LIO fabrics continue to be actively maintained in kernel versions up to 6.x as of 2025, supporting ongoing protocol evolutions without breaking existing deployments.[4]

Supported Protocols

iSCSI

LIO implements the iSCSI protocol through its dedicated fabric module, enabling SCSI commands to be transported over standard TCP/IP networks for remote block storage access.[22] This module, namediscsi_target_mod, operates as part of the kernel-level infrastructure, leveraging the LIO core engine for SCSI command processing while managing the iSCSI-specific transport layer.[22]

The iscsi_target_mod handles TCP connection establishment and maintenance, utilizing the Linux kernel's TCP stack for reliable data transfer, including functions for transmitting and receiving iSCSI Protocol Data Units (PDUs).[22] It supports CHAP (Challenge-Handshake Authentication Protocol) for initiator authentication, which is enabled by default to secure connections by requiring a shared secret between the target and authorized initiators.[18] iSCSI PDU exchanges are processed efficiently, with mechanisms for preparing data-out PDUs and completing SCSI tasks, ensuring compliance with the iSCSI standard for login, negotiation, and full-featured operation phases.[22]

Key features of LIO's iSCSI implementation include support for multiple sessions per target, allowing concurrent connections from initiators to scale access without overwhelming resources; each session can handle up to a configurable maximum number of commands.[22] Digest options provide integrity checking via CRC32C for both headers and data payloads, optional during negotiation to balance security and performance.[22] The module integrates tightly with the kernel TCP stack, enabling hardware offload capabilities where supported by network interfaces to reduce CPU overhead during I/O operations.[22]

Configuration involves setting up portals, which define listening endpoints as IP address and port combinations—typically using the standard iSCSI port 3260—to accept incoming connections.[24] Access Control Lists (ACLs) restrict access by specifying allowed initiator IQNs (iSCSI Qualified Names), ensuring only authorized clients can log in and access LUNs.[31] Parameter negotiation during login includes settings like MaxConnections, which limits the number of concurrent connections per initiator to manage resource allocation.[24]

On standard hardware with 10 Gigabit Ethernet, LIO's iSCSI typically achieves throughputs up to 10 Gbps, approaching line-rate performance for sequential I/O workloads, though actual results depend on network conditions and CPU availability. For higher performance in low-latency environments, RDMA extensions are available via the separate iSER module.[22]

Fibre Channel

LIO provides support for the Fibre Channel protocol through its integration with host bus adapter (HBA) drivers configured in target mode, enabling Linux systems to act as SCSI targets in dedicated Fibre Channel storage area networks (SANs). The primary fabric module for this purpose is tcm_qla2xxx, which leverages the qla2xxx kernel driver to support QLogic HBAs in target mode, handling the low-level Fibre Channel framing and transport.[32] For Emulex (now Broadcom) HBAs, support is available via the lpfc driver, which includes target mode functionality integrated with LIO's core engine.[33] The protocol handling in LIO for Fibre Channel is based on the Fibre Channel Protocol (FCP), which encapsulates SCSI commands, data, and status over Fibre Channel links. This includes standard FC-3 layer operations such as port login (PLOGI) to establish sessions between N_Ports, discovery through the fabric's name server for locating targets and initiators, and support for multipath I/O via the Linux SCSI multipath layer to ensure redundancy and load balancing across multiple paths. LIO's implementation ensures compliance with FCP-4 specifications for reliable SCSI transport in high-performance environments. Hardware dependencies for LIO's Fibre Channel target mode require specific HBA drivers to be loaded and configured appropriately; for instance, the qla2xxx driver must have its qlini_mode parameter set to "disabled" to switch from initiator to target operation, while lpfc requires enabling FC-4 type support for target roles. These drivers interface directly with LIO's target core to expose backstores as logical units (LUNs) over the FC fabric.[34] In datacenter deployments, LIO's Fibre Channel support facilitates seamless integration with enterprise FC switches, enabling fabric-wide zoning for security and isolation, as well as LUN masking through access control lists (ACLs) based on World Wide Port Names (WWPNs) to restrict initiator access to specific LUNs. This capability was introduced in the Linux kernel version 3.5, released in July 2012, allowing LIO to serve as a cost-effective target in heterogeneous SANs.FCoE

LIO's Fibre Channel over Ethernet (FCoE) implementation enables the SCSI target to export storage over Ethernet networks by encapsulating Fibre Channel (FC) frames within Ethernet frames, facilitating converged networking for block storage. This is achieved through the FCoE fabric module, derived from the Open-FCoE project, which integrates with the Linux kernel's libfc and fcoe modules to manage frame encapsulation and decapsulation. The module employs the FCoE Initialization Protocol (FIP) for discovery, allowing targets and initiators to solicit and advertise FCoE capabilities, establish virtual FC links, and perform fabric logins.[35][36] Key features of LIO's FCoE support encompass VLAN tagging to isolate FCoE traffic on dedicated virtual LANs, preventing interference with conventional Ethernet data, and compatibility with Data Center Bridging (DCB) enhancements, including priority-based flow control (PFC), to provide lossless Ethernet transmission essential for reliable storage operations. The FCoE fabric module became part of the mainline Linux kernel in version 3.0, released on July 21, 2011, marking full integration of LIO's target-side FCoE capabilities without requiring userspace daemons for basic operation.[37][38] Compared to native Fibre Channel deployments, LIO's FCoE approach offers significant cost reductions by utilizing existing Ethernet cabling, switches, and NICs for both LAN and SAN traffic, thereby simplifying infrastructure and eliminating the need for dedicated FC hardware. On the target side, LIO processes FCP payloads while preserving core FC semantics, such as zoning and login procedures, for seamless interoperability with FC initiators.[2] Despite these benefits, LIO's FCoE has constraints, including the necessity for specialized FCoE-enabled NICs—such as Broadcom adapters supported via the bnx2fc driver—to enable hardware offload and mitigate CPU overhead. Furthermore, reliance on Ethernet introduces potential latency from packet queuing and contention in shared networks, which can exceed the deterministic performance of pure FC fabrics.[39][40]SRP

LIO's support for the SCSI RDMA Protocol (SRP) is implemented via the srpt kernel module, which serves as the SCSI RDMA Protocol Target for enabling direct data placement using RDMA verbs within the LIO framework.[41] This module was integrated into the upstream Linux kernel with version 3.3, released in March 2012, marking the availability of SRP target functionality in mainline distributions.[42] The SRP protocol operates over InfiniBand fabrics to deliver low-latency I/O by utilizing RDMA mechanisms for connection management, including login and logout sequences that establish and terminate sessions between initiators and targets.[43] It supports immediate data transfers, where SCSI commands and responses can include inline data payloads, further reducing overhead by minimizing CPU involvement in the data movement process during I/O operations. This design ensures efficient access to remote block storage devices, optimizing performance for bandwidth-intensive workloads. Deployment of LIO's SRP requires compatible hardware, such as Mellanox or NVIDIA InfiniBand Host Channel Adapters (e.g., ConnectX series), paired with the OpenFabrics Enterprise Distribution (OFED) software stack to enable RDMA capabilities over InfiniBand and RoCE fabrics.[42] These components facilitate high-bandwidth storage solutions, particularly in high-performance computing (HPC) environments where low-latency remote access to shared storage is critical.[44] The srpt module offers multi-channel support, allowing multiple concurrent connections to scale I/O throughput across sessions, and integrates directly with the Linux kernel's InfiniBand subsystem to operate in target mode alongside LIO's core architecture.[41] This enables seamless configuration of SRP targets using tools like targetcli, exposing backstore devices over RDMA networks without intermediate buffering.[45]iSER

iSER, or iSCSI Extensions for RDMA, provides a transport mechanism within the LIO framework that layers Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) capabilities over the standard iSCSI protocol to enhance performance in high-speed storage networks.[46] This extension maintains the iSCSI control plane semantics for command and response handling while offloading data transfers to RDMA, allowing direct placement of SCSI payloads into target buffers without intermediate copies.[47] Introduced in the Linux kernel version 3.10 in 2013, iSER target support was merged into LIO to enable RDMA-accelerated iSCSI sessions, primarily developed by Nicholas A. Bellinger and integrated via the ib_isert kernel module.[48] The iSER module, known as ib_isert, builds upon the existing iSCSI target module (iscsi_target_mod) for Protocol Data Unit (PDU) processing, including SCSI command encapsulation and login negotiation, while introducing RDMA-specific handling for data phases.[48] It utilizes the RDMA Connection Manager (RDMA/CM) for establishing connections, supporting transports such as iWARP or RoCE over Ethernet, and employs RDMA queue pairs to manage initiator-target communication for reliable, low-latency transfers.[48] A core feature is Direct Data Placement (DDP), which enables RDMA Write and Read operations to deliver SCSI read and write payloads directly to pre-allocated buffers, significantly reducing CPU overhead compared to traditional TCP-based iSCSI by minimizing data copying and protocol processing in the kernel.[46] For integrity, iSER incorporates Steering Tag (STag) validation, where the target verifies STags provided by the initiator in iSER headers to ensure correct buffer placement and prevent data corruption, with automatic invalidation upon task completion.[46] This mechanism, combined with RDMA's built-in error detection like CRC, provides robust protection during transfers.[46] In deployment, iSER is particularly effective in environments with 10 Gbps or higher Ethernet networks equipped with RDMA-capable NICs, such as those supporting RoCE, allowing LIO targets to achieve higher throughput and lower latency for block storage access in data centers or clustered systems.[47] Configuration typically involves loading the ib_isert module alongside core LIO components and using tools like targetcli to set up iSCSI targets with iSER transport.[48]USB

LIO provides support for SCSI over USB through its usb_gadget fabric module, allowing Linux systems equipped with USB device controllers to emulate SCSI targets in gadget mode, thereby exporting local storage to USB hosts. This integration enables the Universal Serial Bus Mass Storage Class (MSC) emulation, where LIO processes incoming SCSI commands received via USB bulk transfers. The module was merged into the mainline Linux kernel with version 3.1, released on October 24, 2011, building on the existing gadget framework to support target functionality. The implementation leverages the USB gadget API to handle device-side USB operations, with LIO's core target engine managing the SCSI command processing independently of the transport layer. It supports two primary protocols: Bulk-Only Transport (BOT), compliant with USB 2.0 MSC specifications for basic bulk transfers, and USB Attached SCSI Protocol (UASP), which utilizes USB 3.0 bulk streams for asynchronous command queuing and improved throughput. UASP enables multiple outstanding commands, reducing latency in command-response cycles compared to BOT's single-command limitation, while LIO translates these into standard SCSI operations for backstore handling. This setup requires enabling the CONFIG_USB_GADGET_TARGET kernel configuration, which registers the fabric module under the generic target core (TCM/LIO) infrastructure.[49][50] In practice, the USB fabric is particularly suited for embedded devices and single-host peripherals, such as exporting block devices from resource-constrained systems like Raspberry Pi or IoT gateways to act as USB drives for connected hosts. Deployment typically involves composite gadget drivers, combining the SCSI target function with other USB classes (e.g., via ConfigFS for dynamic configuration), and relies on LIO's backstore components for underlying storage abstraction. For instance, it facilitates scenarios where a Linux-based device presents cloud-backed volumes (e.g., Ceph RBD images) as local USB storage, enabling legacy devices like media players or automotive systems to access remote data without native network support.[50] Despite its versatility for peripheral applications, the USB fabric exhibits limitations in performance relative to network-based protocols like iSCSI or Fibre Channel, with maximum throughputs constrained by USB 3.0's 5 Gbit/s theoretical limit and overhead from gadget emulation. It is optimized for low-latency, point-to-point connections rather than scalable Storage Area Network (SAN) environments, and requires hardware support for USB On-The-Go (OTG) or dedicated device controllers to avoid host-only modes. Additionally, while UASP mitigates some bottlenecks, real-world transfers remain below those of dedicated fabrics due to USB's polling-based nature and lack of multi-initiator support.[49]IEEE 1394

LIO provides legacy support for exporting SCSI targets over IEEE 1394 (FireWire) through the firewire-target module, which implements the Serial Bus Protocol 2 (SBP-2) for transporting SCSI commands. This module was integrated into the LIO framework in the Linux kernel around version 3.4, released in May 2012, enabling Linux systems to act as SBP-2 targets on the FireWire bus.[51][30] The SBP-2 protocol facilitates asynchronous transfers of SCSI commands and data over the IEEE 1394 serial bus, encapsulating SCSI Command Descriptor Blocks (CDBs) within SBP-2 request and response blocks to handle operations like read/write without relying on isochronous streams. Node discovery occurs during bus initialization, where attached devices perform self-identification (Self-ID) packets to establish the tree topology, allowing initiators to enumerate and address targets dynamically across the bus.[52][53] Hardware support requires compatible IEEE 1394 controllers, such as those driven by the ohci-1394 module, which handles the Open Host Controller Interface (OHCI) for FireWire host adapters. These controllers enable the physical layer connectivity for SBP-2 operations, though FireWire hardware has largely been supplanted by USB and Thunderbolt interfaces in modern systems.[54] As of 2025, the firewire-target module remains maintained in the Linux kernel for backward compatibility, with ongoing refinements to the IEEE 1394 subsystem in versions like 6.18, but its use is rare due to the obsolescence of FireWire technology and the prevalence of faster alternatives.[55][54]Configuration and Management

Targetcli Tool

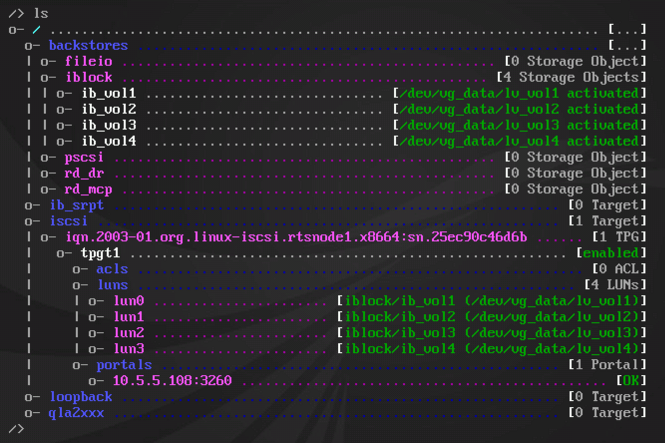

Targetcli is a Python-based command-line shell originally developed by RisingTide Systems (now Datera) for configuring and managing LIO SCSI targets in the Linux kernel. A community-maintained fork, targetcli-fb, is widely used in distributions such as Debian, Fedora, and openSUSE due to active development.[56] It offers a hierarchical, tree-like navigation structure modeled after a filesystem, allowing administrators to organize and manipulate storage backstores, logical targets, and fabric modules through intuitive paths such as/backstores, /iscsi, and /iscsi/<iqn>/tpg1/acls. This design simplifies the setup of SCSI targets by abstracting the underlying configfs interface provided by LIO.[57][58]

Core functionality revolves around key commands for creating and managing resources. For instance, backstores can be initialized with /backstores/fileio create <name> <path> <size>, which sets up a file-based storage object like a virtual disk image. iSCSI targets are then created using /iscsi create iqn.<domain>:<node>, enabling the export of backstores as LUNs over the network. Configurations are made persistent across reboots via the saveconfig command, which serializes the setup to /etc/target/saveconfig.[json](/page/JSON) and applies it through configfs on startup.[58][28]

The tool includes an interactive shell with tab-based autocomplete for commands and arguments, inline documentation accessible via help or ?, and built-in support for Access Control Lists (ACLs) through commands like /iscsi/<target>/tpg1/acls create <initiator_iqns>, which restricts LUN access to authorized initiators. Since 2014, targetcli has integrated with systemd via the target.service unit, allowing seamless service enabling and management with systemctl enable target to ensure automatic loading of saved configurations.[58][28]

Installation is straightforward in major distributions; for example, in SUSE Linux Enterprise Server, it is provided as the targetcli-fb package installable via zypper install targetcli-fb. For the most recent versions as of 2025, users can build from the official GitHub repositories, which support RPM and Debian packaging through provided make targets.[7][57][56]

Kernel Module Setup

The core LIO kernel module,target_core_mod, provides the foundational SCSI target engine and must be loaded before any fabric-specific modules. This is typically done using modprobe target_core_mod, which automatically resolves dependencies such as the configfs filesystem mounted at /sys/kernel/config. For protocol support, subsequent modules like iscsi_target_mod for iSCSI are loaded via modprobe iscsi_target_mod, enabling the corresponding fabric operations.[25][18]

LIO configuration occurs primarily through the configfs interface at /sys/kernel/config/target/core, allowing direct kernel-level tuning of parameters without intermediary userspace tools like targetcli. For instance, iSCSI session parameters such as max_cmd_sn can be adjusted in the session attributes to control command sequence numbering and prevent overflows. Security-related settings, including generate_node_acls=1 on target portal groups, automate the creation of node access control lists (ACLs) to restrict initiator access by default.[22][59]

For boot-time integration in embedded or minimal environments, LIO modules are included in the initramfs using dracut by invoking dracut --add-drivers "target_core_mod iscsi_target_mod" during image generation, ensuring early availability for root filesystem mounting over SCSI targets. Dynamic LUN exposure can be managed with udev rules that trigger on configfs events, such as creating symlinks or permissions for newly registered logical units under /dev.[60]

Troubleshooting LIO setup involves examining kernel logs via dmesg for module registration confirmations, such as "target_core_mod: loading out-of-tree module tcm_user" or fabric binding messages, and error indicators like failed configfs mounts. Common issues include missing dependencies, resolvable by verifying lsmod output and reloading with explicit parameters like generate_node_acls=1 for ACL enforcement during initialization.[61][62]

Deployment in Linux

Integration in Distributions

LIO has been integrated into major Linux distributions since its upstream inclusion in the Linux kernel, providing native support for SCSI target functionality without requiring additional out-of-tree modules. As of 2025, this integration varies by distribution in terms of packaging, default enablement, and management tools, facilitating easier deployment for storage administrators. As of November 2025, LIO remains integrated in the latest kernels for these distributions, with ongoing updates for compatibility. In Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) and derivatives like CentOS, LIO has been the default for iSCSI targets since RHEL 7, released in 2014, allowing users to configure them directly through kernel modules. It was included in RHEL 6 but primarily for FCoE targets. The targetcli administration tool is provided via the storage-tools package, which includes utilities for managing LIO configurations, and can be enabled through the Cockpit web-based GUI module cockpit-storage for simplified setup in enterprise environments. This setup supports high-availability clustering, as detailed in official guides for RHEL 8 and 9. For Debian and Ubuntu, LIO is available through the linux-modules-extra kernel package, which includes the necessary target_core_mod and related modules for extra functionality beyond the base kernel. Configuration is handled via targetcli, installable from the universe repository, with support extended to recent kernels such as version 6.8 and later through updated module packages in Ubuntu 24.04 LTS and Debian 12. The Debian wiki provides detailed instructions for enabling LIO as an in-kernel iSCSI target, emphasizing its use in software-defined storage setups. SUSE Linux Enterprise Server (SLES) and openSUSE have included LIO by default since SLES 12, introduced in 2014, with kernel modules activated for iSCSI and other protocols out of the box. Integration with the YaST configuration tool allows straightforward setup of iSCSI LIO targets via the yast2-iscsi-lio-server module, including options for high-availability clustering as outlined in official documentation for SLES 12 SP5 and later. This enables seamless management in enterprise clusters, with packages like targetcli available through zypper for advanced scripting. Arch Linux and Fedora maintain standard kernel inclusion of LIO, with the target fabric modules present since Linux kernel 3.1, ensuring compatibility in their respective releases. In Arch Linux, a rolling-release distribution, targetcli is accessible via the AUR package targetcli-fb or directly from PyPI for Python-based installations, allowing users to benefit from the latest LIO fixes and upstream enhancements without version lag. Fedora similarly embeds LIO in its kernel since Fedora 17, with targetcli installable via DNF, supporting rapid iteration on storage features in development and testing workflows.Practical Use Cases

LIO serves as a versatile SCSI target framework in practical deployments, enabling efficient block storage sharing across diverse environments. In small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs), LIO facilitates the creation of cost-effective iSCSI storage area networks (SANs) by exporting NAS volumes to Windows and Linux clients over Ethernet, leveraging its integration into standard Linux distributions for simplified management and scalability.[24] High availability is achieved through integration with Pacemaker, allowing automatic failover of iSCSI targets to ensure continuous access during node failures, as demonstrated in clustered setups on RHEL 9.[63] In virtualization environments, LIO targets provide dedicated storage for KVM and QEMU-based virtual machines, supporting paravirtualized I/O via vhost-scsi for reduced overhead and enhanced throughput. The worker_per_virtqueue feature for vhost-scsi, introduced in the Linux kernel 6.5, enables multiple worker threads per virtqueue for better I/O parallelism. This is available in upstream kernels and Oracle's UEK-next preview based on kernel 6.10 (as of September 2024), improving scaling in iSCSI workloads for VM storage.[64] For embedded and IoT applications, LIO enables Raspberry Pi devices to act as portable storage targets by exporting attached USB drives over iSCSI, suitable for lightweight, mobile data sharing in field deployments or homelabs. Additionally, LIO's SRP support allows shared disk access in high-performance computing (HPC) clusters over InfiniBand networks, utilizing RDMA for low-latency, high-throughput block storage in multi-node environments.[65][66] In clustered storage scenarios, LIO integrates with DRBD and LINSTOR to deliver highly available iSCSI targets, as updated in 2024 guides for RHEL 9, where Pacemaker orchestrates seamless failover without downtime by promoting DRBD resources and restarting targets on healthy nodes.[10][67]References

- https://wiki.alpinelinux.org/wiki/Linux_iSCSI_Target_%28TCM%29