Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

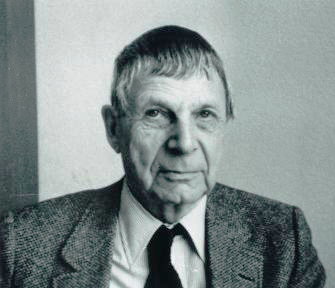

Lars Ahlfors

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2020) |

Lars Valerian Ahlfors (18 April 1907 – 11 October 1996) was a Finnish mathematician, remembered for his work in the field of Riemann surfaces and his textbook on complex analysis. In 1936, Ahlfors was awarded the first Fields Medal, along with American mathematician Jesse Douglas.[citation needed]

Key Information

Background

[edit]Ahlfors was born in Helsinki, Finland.[1][2] His mother, Sievä Helander, died at his birth. His father, Axel Ahlfors, was a professor of engineering at the Helsinki University of Technology. The Ahlfors family was Swedish-speaking, so he first attended the private school Nya svenska samskolan where all classes were taught in Swedish. Ahlfors studied at University of Helsinki from 1924, graduating in 1928 having studied under Ernst Lindelöf and Rolf Nevanlinna.[1] He assisted Nevanlinna in 1929 with his work on Denjoy's conjecture on the number of asymptotic values of an entire function. In 1929 Ahlfors published the first proof of this conjecture, now known as the Denjoy–Carleman–Ahlfors theorem.[3] It states that the number of asymptotic values approached by an entire function of order ρ along curves in the complex plane going toward infinity is less than or equal to 2ρ.

He completed his doctorate from the University of Helsinki in 1930.

Career

[edit]Ahlfors worked as an associate professor at the University of Helsinki from 1933 to 1936. In 1936 he was one of the first two people to be awarded the Fields Medal[1][2] (the other was Jesse Douglas). In 1935 Ahlfors visited Harvard University.[2] He returned to Finland in 1938 to take up a professorship at the University of Helsinki. The outbreak of war in 1939 led to problems although Ahlfors was unfit for military service. He was offered a position at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology at Zurich in 1944 and finally managed to travel there in March 1945. He did not enjoy his time in Switzerland, so in 1946 he jumped at a chance to leave, returning to work at Harvard, where he remained until his retirement in 1977;[1][2] he was William Caspar Graustein Professor of Mathematics from 1964. Ahlfors was a visiting scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study in 1962 and again in 1966.[4] He was awarded the Wihuri International Prize in 1968 and the Wolf Prize in Mathematics in 1981. He served as the Honorary President of the International Congress of Mathematicians in 1986 at Berkeley, California, in celebration of his 50th year of the award of his Fields Medal.

His book Complex Analysis (1953) is the classic text on the subject and is almost certainly referenced in any more recent text which makes heavy use of complex analysis. Ahlfors wrote several other significant books, including Riemann surfaces (1960)[5] and Conformal invariants (1973). He made decisive contributions to meromorphic curves, value distribution theory, Riemann surfaces, conformal geometry, quasiconformal mappings and other areas during his career.

Personal life

[edit]In 1933, he married Erna Lehnert, an Austrian who with her parents had first settled in Sweden and then in Finland. The couple had three daughters. Ahlfors died of pneumonia at the Willowwood nursing home in Pittsfield, Massachusetts in 1996.[1][2]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]Articles

[edit]- Ahlfors, Lars V. An extension of Schwarz's lemma. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 43 (1938), no. 3, 359–364. doi:10.2307/1990065

- Ahlfors, Lars; Beurling, Arne. Conformal invariants and function-theoretic null-sets. Acta Math. 83 (1950), 101–129. doi:10.1007/BF02392634

- Beurling, A.; Ahlfors, L. The boundary correspondence under quasiconformal mappings. Acta Math. 96 (1956), 125–142. doi:10.1007/BF02392360

- Ahlfors, Lars; Bers, Lipman. Riemann's mapping theorem for variable metrics. Ann. of Math. (2) 72 (1960), 385–404. doi:10.2307/1970141

- Ahlfors, Lars Valerian. Collected papers. Vol. 1. 1929–1955. Edited with the assistance of Rae Michael Shortt. Contemporary Mathematicians. Birkhäuser, Boston, Mass., 1982. xix+520 pp. ISBN 3-7643-3075-9

- Ahlfors, Lars Valerian. Collected papers. Vol. 2. 1954–1979. Edited with the assistance of Rae Michael Shortt. Contemporary Mathematicians. Birkhäuser, Boston, Mass., 1982. xix+515 pp. ISBN 3-7643-3076-7

Books

[edit]- Ahlfors, Lars V. Complex analysis. An introduction to the theory of analytic functions of one complex variable. Third edition. International Series in Pure and Applied Mathematics. McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1978. xi+331 pp. ISBN 0-07-000657-1[6]

- Ahlfors, Lars V. Conformal invariants. Topics in geometric function theory. Reprint of the 1973 original. With a foreword by Peter Duren, F. W. Gehring and Brad Osgood. AMS Chelsea Publishing, Providence, RI, 2010. xii+162 pp. ISBN 978-0-8218-5270-5

- Ahlfors, Lars V. Lectures on quasiconformal mappings. Second edition. With supplemental chapters by C. J. Earle, I. Kra, M. Shishikura and J. H. Hubbard. University Lecture Series, 38. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2006. viii+162 pp. ISBN 0-8218-3644-7

- Ahlfors, Lars V. Möbius transformations in several dimensions. Ordway Professorship Lectures in Mathematics. University of Minnesota, School of Mathematics, Minneapolis, Minn., 1981. ii+150 pp.

- Ahlfors, Lars V.; Sario, Leo. Riemann surfaces. Princeton Mathematical Series, No. 26 Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. 1960 xi+382 pp.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Lars V. Ahlfors, Mathematician Who Won First Fields Medal; 89". The Boston Globe. Boston, MA. October 17, 1996. p. 87. Retrieved August 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e "Lars Ahlfors, Leading Mathematician in Complex Analysis, Dies at 89". The Fresno Bee. Fresno, CA. October 23, 1996. p. 42. Retrieved August 14, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ahlfors, Lars Valerian (2015-12-08). Analytic Functions. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7670-9.

- ^ Institute for Advanced Study: A Community of Scholars

- ^ Springer, George. "Review of Riemann surfaces. By Lars V. Ahlfors and Leo Sario" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 67 (2): 170–171. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1961-10548-X.

- ^ Schaeffer, A. C. (1953). "Review: Complex analysis. By Lars V. Ahlfors" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 59 (5): 464–467. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1953-09722-1.

External links

[edit] Media related to Lars Ahlfors at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lars Ahlfors at Wikimedia Commons- Lars Ahlfors at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Ahlfors entry on Harvard University Mathematics department web site.

- Papers of Lars Valerian Ahlfors : an inventory (Harvard University Archives)

- Lars Valerian Ahlfors The MacTutor History of Mathematics page about Ahlfors

- The Mathematics of Lars Valerian Ahlfors, Notices of the American Mathematical Society; vol. 45, no. 2 (February 1998).

- Lars Valerian Ahlfors (1907–1996), Notices of the American Mathematical Society; vol. 45, no. 2 (February 1998).

- Frederick Gehring (2005). "Lars Valerian Ahlfors: a biographical memoir" (PDF). Biographical Memoirs. 87.

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

- Author profile in the database zbMATH