Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Integrated circuit

View on Wikipedia

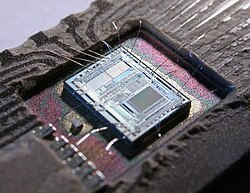

An integrated circuit (IC), also known as a microchip or simply chip, is a compact assembly of electronic circuits formed from various electronic components — such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors — and their interconnections.[1] These components are fabricated onto a thin, flat piece ("chip") of semiconductor material, most commonly silicon.[1] Integrated circuits are integral to a wide variety of electronic devices — including computers, smartphones, and televisions — performing functions such as data processing, control, and storage. They have transformed the field of electronics by enabling device miniaturization, improving performance, and reducing cost.

Compared to assemblies built from discrete components, integrated circuits are orders of magnitude smaller, faster, more energy-efficient, and less expensive, allowing for a very high transistor count.

The IC’s capability for mass production, its high reliability, and the standardized, modular approach of integrated circuit design facilitated rapid replacement of designs using discrete transistors. Today, ICs are present in virtually all electronic devices and have revolutionized modern technology. Products such as computer processors, microcontrollers, digital signal processors, and embedded chips in home appliances are foundational to contemporary society due to their small size, low cost, and versatility.

Very-large-scale integration was made practical by technological advancements in semiconductor device fabrication. Since their origins in the 1960s, the size, speed, and capacity of chips have progressed enormously, driven by technical advances that fit more and more transistors on chips of the same size – a modern chip may have many billions of transistors in an area the size of a human fingernail. These advances, roughly following Moore's law, make the computer chips of today possess millions of times the capacity and thousands of times the speed of the computer chips of the early 1970s.

ICs have three main advantages over circuits constructed out of discrete components: size, cost and performance. The size and cost is low because the chips, with all their components, are printed as a unit by photolithography rather than being constructed one transistor at a time. Furthermore, packaged ICs use much less material than discrete circuits. Performance is high because the IC's components switch quickly and consume comparatively little power because of their small size and proximity. The main disadvantage of ICs is the high initial cost of designing them and the enormous capital cost of factory construction. This high initial cost means ICs are only commercially viable when high production volumes are anticipated.

Terminology

[edit]An integrated circuit (IC) is formally defined as:[2]

A circuit in which all or some of the circuit elements are inseparably associated and electrically interconnected so that it is considered to be indivisible for the purposes of construction and commerce.

In its strict sense, the term refers to a single-piece circuit construction — originally called a monolithic integrated circuit — consisting of an entire circuit built on a single piece of silicon.[3][4] In general usage, the designation "integrated circuit" can also apply to circuits that do not meet this strict definition, and which may be constructed using various technologies such as 3D IC, 2.5D IC, MCM, thin-film transistors, thick-film technology, or hybrid integrated circuits. This distinction in terminology is often relevant in debates on whether Moore's law remains applicable.

History

[edit]The first integrated circuits

[edit]

A precursor concept to the IC was the development of small ceramic substrates, known as micromodules,[5] each containing a single miniaturized electronic component. These modules could then be assembled and interconnected into a two- or three-dimensional compact grid. The idea, considered highly promising in 1957, was proposed to the U.S. Army by Jack Kilby,[5] leading to the short-lived Micromodule Program (similar in spirit to 1951's Project Tinkertoy).[5][6][7] However, as the project gained traction, Kilby devised a fundamentally new approach: the integrated circuit itself.

Newly employed by Texas Instruments, Kilby recorded his initial ideas concerning the integrated circuit in July 1958, successfully demonstrating the first working example of an integrated circuit on 12 September 1958.[8] In his patent application of 6 February 1959,[9] Kilby described his new device as "a body of semiconductor material … wherein all the components of the electronic circuit are completely integrated".[10] The first customer for the new invention was the US Air Force.[11] Kilby won the 2000 Nobel Prize in physics for his part in the invention of the integrated circuit.[12]

However, Kilby's invention was not a true monolithic integrated circuit chip, as it relied on external gold-wire connections, making large-scale production impractical.[13] About six months later, Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor developed the first practical monolithic IC chip.[14][13] The monolithic integrated circuit chip was enabled by the inventions of the planar process by Jean Hoerni and of p–n junction isolation by Kurt Lehovec. Hoerni's invention was built on Carl Frosch and Lincoln Derick's work on surface protection and passivation by silicon dioxide masking and predeposition,[15][16][17] as well as Fuller, Ditzenberger's and others work on the diffusion of impurities into silicon.[18][19][20][21][22]

Unlike Kilby's germanium-based design, Noyce's version was fabricated from silicon using the planar process by his colleague Jean Hoerni, which allowed reliable on-chip aluminum interconnections. Modern IC chips are based on Noyce's monolithic design,[14][13] rather than Kilby's early prototype.

NASA's Apollo Program was the largest single consumer of integrated circuits between 1961 and 1965.[23]

TTL integrated circuits

[edit]Transistor–transistor logic (TTL) was developed by James L. Buie in the early 1960s at TRW Inc. TTL became the dominant integrated circuit technology during the 1970s to early 1980s.[24]

Use of dozens of TTL integrated circuits was the standard method of construction for the processors of minicomputers and mainframe computers. Computers such as IBM 360 mainframes, PDP-11 minicomputers and the desktop Datapoint 2200 were built from bipolar integrated circuits,[25] either TTL or the faster emitter-coupled logic (ECL).

MOS integrated circuits

[edit]Modern integrated circuits (ICs) are based on the metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET), forming MOS ICs.[26] The MOSFET was developed at Bell Labs between 1955 and 1960,[15][27][16][28][29][30][17] enabling the creation of high-density ICs.[31] Unlike bipolar transistors, which required additional steps for p–n junction isolation, MOSFETs could be easily isolated from one another without such measures.[32] This advantage for integrated circuits was first highlighted by Dawon Kahng in 1961.[33] The list of IEEE Milestones includes Kilby's first IC in 1958,[34] Hoerni's planar process and Noyce's planar IC in 1959.[35]

The earliest experimental MOS IC to be fabricated was a 16-transistor chip built by Fred Heiman and Steven Hofstein at RCA in 1962.[36] General Microelectronics later introduced the first commercial MOS integrated circuit in 1964,[37] a 120-transistor shift register developed by Robert Norman.[36] By 1964, MOS chips had reached higher transistor density and lower manufacturing costs than bipolar chips. MOS chips further increased in complexity at a rate predicted by Moore's law, leading to large-scale integration (LSI) with hundreds of transistors on a single MOS chip by the late 1960s.[38]

Following the development of the self-aligned gate (silicon-gate) MOSFET by Robert Kerwin, Donald Klein and John Sarace at Bell Labs in 1967,[39] the first silicon-gate MOS IC technology with self-aligned gates, the basis of all modern CMOS integrated circuits, was developed at Fairchild Semiconductor by Federico Faggin in 1968.[40] The application of MOS LSI chips to computing was the basis for the first microprocessors, as engineers began recognizing that a complete computer processor could be contained on a single MOS LSI chip. This led to the inventions of the microprocessor and the microcontroller by the early 1970s.[38] During the early 1970s, MOS integrated circuit technology enabled the very large-scale integration (VLSI) of more than 10,000 transistors on a single chip.[41]

At first, MOS-based computers only made sense when high density was required, such as aerospace and pocket calculators. Computers built entirely from TTL, such as the 1970 Datapoint 2200, were much faster and more powerful than single-chip MOS microprocessors, such as the 1972 Intel 8008, until the early 1980s.[25]

Advances in IC technology, primarily smaller features and larger chips, have allowed the number of MOS transistors in an integrated circuit to double every two years, a trend known as Moore's law. Moore originally stated it would double every year, but he went on to change the claim to every two years in 1975.[42] This increased capacity has been used to decrease cost and increase functionality. In general, as the feature size shrinks, almost every aspect of an IC's operation improves. The cost per transistor and the switching power consumption per transistor goes down, while the memory capacity and speed go up, through the relationships defined by Dennard scaling (MOSFET scaling).[43] Because speed, capacity, and power consumption gains are apparent to the end user, there is fierce competition among the manufacturers to use finer geometries. Over the years, transistor sizes have decreased from tens of microns in the early 1970s to 10 nanometers in 2017[44] with a corresponding million-fold increase in transistors per unit area. As of 2016, typical chip areas range from a few square millimeters to around 600 mm2, with up to 25 million transistors per mm2.[45]

The expected shrinking of feature sizes and the needed progress in related areas was forecast for many years by the International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors (ITRS). The final ITRS was issued in 2016, and it is being replaced by the International Roadmap for Devices and Systems.[46]

Initially, ICs were strictly electronic devices. The success of ICs has led to the integration of other technologies, in an attempt to obtain the same advantages of small size and low cost. These technologies include mechanical devices, optics, and sensors.

- Charge-coupled devices, and the closely related active-pixel sensors, are chips that are sensitive to light. They have largely replaced photographic film in scientific, medical, and consumer applications. Billions of these devices are now produced each year for applications such as cellphones, tablets, and digital cameras. This sub-field of ICs won the Nobel Prize in 2009.[47]

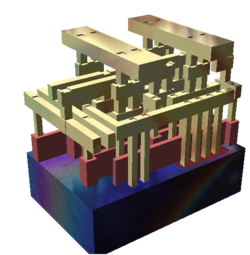

- Very small mechanical devices driven by electricity can be integrated onto chips, a technology known as microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). These devices were developed in the late 1980s[48] and are used in a variety of commercial and military applications. Examples include DLP projectors, inkjet printers, and accelerometers and MEMS gyroscopes used to deploy automobile airbags.

- Since the early 2000s, the integration of optical functionality (optical computing) into silicon chips has been actively pursued in both academic research and in industry resulting in the successful commercialization of silicon based integrated optical transceivers combining optical devices (modulators, detectors, routing) with CMOS based electronics.[49] Photonic integrated circuits that use light such as Lightelligence's PACE (Photonic Arithmetic Computing Engine) also being developed, using the emerging field of physics known as photonics.[50]

- Integrated circuits are also being developed for sensor applications in medical implants or other bioelectronic devices.[51] Special sealing techniques have to be applied in such biogenic environments to avoid corrosion or biodegradation of the exposed semiconductor materials.[52]

As of 2018[update], the vast majority of all transistors are MOSFETs fabricated in a single layer on one side of a chip of silicon in a flat two-dimensional planar process. Researchers have produced prototypes of several promising alternatives, such as:

- various approaches to stacking several layers of transistors to make a three-dimensional integrated circuit (3DIC), such as through-silicon via, "monolithic 3D",[53] stacked wire bonding,[54] and other methodologies.

- transistors built from other materials: graphene transistors, molybdenite transistors, carbon nanotube field-effect transistor, gallium nitride transistor, transistor-like nanowire electronic devices, organic field-effect transistor, etc.

- fabricating transistors over the entire surface of a small sphere of silicon.[55][56]

- modifications to the substrate, typically to make "flexible transistors" for a flexible display or other flexible electronics, possibly leading to a roll-away computer.

As it becomes more difficult to manufacture ever smaller transistors, companies are using multi-chip modules/chiplets, three-dimensional integrated circuits, package on package, High Bandwidth Memory and through-silicon vias with die stacking to increase performance and reduce size, without having to reduce the size of the transistors. Such techniques are collectively known as advanced packaging.[57] Advanced packaging is mainly divided into 2.5D and 3D packaging. 2.5D describes approaches such as multi-chip modules while 3D describes approaches where dies are stacked in one way or another, such as package on package and high bandwidth memory. All approaches involve 2 or more dies in a single package.[58][59][60][61][62] Alternatively, approaches such as 3D NAND stack multiple layers on a single die. A technique has been demonstrated to include microfluidic cooling on integrated circuits, to improve cooling performance[63] as well as peltier thermoelectric coolers on solder bumps, or thermal solder bumps used exclusively for heat dissipation, used in flip-chip.[64][65]

Design

[edit]

The cost of designing and developing a complex integrated circuit is quite high, normally in the multiple tens of millions of dollars.[66][67] Therefore, it only makes economic sense to produce integrated circuit products with high production volume, so the non-recurring engineering (NRE) costs are spread across typically millions of production units.

Modern semiconductor chips have billions of components, and are far too complex to be designed by hand. Software tools to help the designer are essential. Electronic design automation (EDA), also referred to as electronic computer-aided design (ECAD),[68] is a category of software tools for designing electronic systems, including integrated circuits. The tools work together in a design flow that engineers use to design, verify, and analyze entire semiconductor chips. Some of the latest EDA tools use artificial intelligence (AI) to help engineers save time and improve chip performance.

Types

[edit]

Integrated circuits can be broadly classified into analog,[69] digital[70] and mixed-signal,[71] consisting of analog and digital signaling on the same IC.

Digital integrated circuits can contain billions[45] of logic gates, flip-flops, multiplexers, and other circuits in a few square millimeters. The small size of these circuits allows high speed, low power dissipation, and reduced manufacturing cost compared with board-level integration. These digital ICs, typically microprocessors, DSPs, and microcontrollers, use boolean algebra to process "one" and "zero" signals.

Among the most advanced integrated circuits are the microprocessors or "cores", used in personal computers, cell-phones, etc. Several cores may be integrated together in a single IC or chip. Digital memory chips and application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) are examples of other families of integrated circuits.

In the 1980s, programmable logic devices were developed. These devices contain circuits whose logical function and connectivity can be programmed by the user, rather than being fixed by the integrated circuit manufacturer. This allows a chip to be programmed to do various LSI-type functions such as logic gates, adders and registers. Programmability comes in various forms – devices that can be programmed only once, devices that can be erased and then re-programmed using UV light, devices that can be (re)programmed using flash memory, and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) which can be programmed at any time, including during operation. Current FPGAs can (as of 2016) implement the equivalent of millions of gates and operate at frequencies up to 1 GHz.[72]

Analog ICs, such as sensors, power management circuits, and operational amplifiers (op-amps), process continuous signals, and perform analog functions such as amplification, active filtering, demodulation, and mixing.

ICs can combine analog and digital circuits on a chip to create functions such as analog-to-digital converters and digital-to-analog converters. Such mixed-signal circuits offer smaller size and lower cost, but must account for signal interference. Prior to the late 1990s, radios could not be fabricated in the same low-cost CMOS processes as microprocessors. But since 1998, radio chips have been developed using RF CMOS processes. Examples include Intel's DECT cordless phone, or 802.11 (Wi-Fi) chips created by Atheros and other companies.[73]

Modern electronic component distributors often further sub-categorize integrated circuits:

- Digital ICs are categorized as logic ICs (such as microprocessors and microcontrollers), memory chips (such as MOS memory and floating-gate memory), interface ICs (level shifters, serializer/deserializer, etc.), power management ICs, and programmable devices.

- Analog ICs are categorized as linear integrated circuits and RF circuits (radio frequency circuits).

- Mixed-signal integrated circuits are categorized as data acquisition ICs (including A/D converters, D/A converters, digital potentiometers), clock/timing ICs, switched capacitor (SC) circuits, and RF CMOS circuits.

- Three-dimensional integrated circuits (3D ICs) are categorized into through-silicon via (TSV) ICs and Cu-Cu connection ICs.

Manufacturing

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

Fabrication

[edit]

The semiconductors of the periodic table of the chemical elements were identified as the most likely materials for a solid-state vacuum tube. Starting with copper oxide, proceeding to germanium, then silicon, the materials were systematically studied in the 1940s and 1950s. Today, monocrystalline silicon is the main substrate used for ICs although some III-V compounds of the periodic table such as gallium arsenide are used for specialized applications like LEDs, lasers, solar cells and the highest-speed integrated circuits. It took decades to perfect methods of creating crystals with minimal defects in semiconducting materials' crystal structure.

Semiconductor ICs are fabricated in a planar process which includes three key process steps – photolithography, deposition (such as chemical vapor deposition), and etching. The main process steps are supplemented by doping and cleaning. More recent or high-performance ICs may instead use multi-gate FinFET or GAAFET transistors instead of planar ones, starting at the 22 nm node (Intel) or 16/14 nm nodes.[74]

Mono-crystal silicon wafers are used in most applications (or for special applications, other semiconductors such as gallium arsenide are used). The wafer need not be entirely silicon. Photolithography is used to mark different areas of the substrate to be doped or to have polysilicon, insulators or metal (typically aluminium or copper) tracks deposited on them. Dopants are impurities intentionally introduced to a semiconductor to modulate its electronic properties. Doping is the process of adding dopants to a semiconductor material.

- Integrated circuits are composed of many overlapping layers, each defined by photolithography, and normally shown in different colors. Some layers mark where various dopants are diffused into the substrate (called diffusion layers), some define where additional ions are implanted (implant layers), some define the conductors (doped polysilicon or metal layers), and some define the connections between the conducting layers (via or contact layers). All components are constructed from a specific combination of these layers.

- In a self-aligned CMOS process, a transistor is formed wherever the gate layer (polysilicon or metal) crosses a diffusion layer (this is called "the self-aligned gate").[75]: p.1 (see Fig. 1.1)

- Capacitive structures, in form very much like the parallel conducting plates of a traditional electrical capacitor, are formed according to the area of the "plates", with insulating material between the plates. Capacitors of a wide range of sizes are common on ICs.

- Meandering stripes of varying lengths are sometimes used to form on-chip resistors, though most logic circuits do not need any resistors. The ratio of the length of the resistive structure to its width, combined with its sheet resistivity, determines the resistance.

- More rarely, inductive structures can be built as tiny on-chip coils, or simulated by gyrators.

Since a CMOS device only draws current on the transition between logic states, CMOS devices consume much less current than bipolar junction transistor devices.

Random-access memory (RAM) is the most regular type of integrated circuit; the highest-density ICs are therefore memories, although even a microprocessor typically includes on-chip memory. (See the regular array structure at the bottom of the first image.[which?]) Although device structures are highly intricate—with feature widths that have been shrinking for decades—the material layers remain much thinner than the lateral dimensions of the devices. These layers are fabricated using a process analogous to photolithography, but light in the visible spectrum cannot be used for patterning, as its wavelengths are too large. Instead, ultraviolet (UV) photons of shorter wavelength are employed to expose each layer. Because the features are so small, electron microscopes are essential tools for a process engineer working on fabrication process debugging.

Each device is tested before packaging using automated test equipment (ATE), in a procedure known as wafer testing or wafer probing. The wafer is then cut into rectangular blocks, each known as a die. Each functional die (plural dice, dies, or die) is connected into a package using aluminium (or gold) bond wires, which are attached by thermosonic bonding.[76] Thermosonic bonding, first introduced by A. Coucoulas, provided a reliable means of forming electrical connections between the die and the outside world. After packaging, devices undergo final testing on the same or similar ATE used during wafer probing. In addition, industrial CT scanning can be employed for inspection. Test cost can account for over 25% of total fabrication cost for low-cost products, but is relatively negligible for low-yielding, larger, or higher-cost devices.

As of 2022[update], a fabrication facility (commonly known as a semiconductor fab) can cost over US$12 billion to construct.[77] The cost of a fabrication facility rises over time because of increased complexity of new products; this is known as Rock's law. Such a facility features:

- The wafers up to 300 mm in diameter (wider than a common dinner plate).

- As of 2022[update], 5 nm transistors.

- Copper interconnects where copper wiring replaces aluminum for interconnects.

- Low-κ dielectric insulators.

- Silicon on insulator (SOI).

- Strained silicon in a process used by IBM known as Strained silicon directly on insulator (SSDOI).

- Multigate devices such as tri-gate transistors.

ICs can be manufactured either in-house by integrated device manufacturers (IDMs) or using the foundry model. IDMs are vertically integrated companies (like Intel and Samsung) that design, manufacture and sell their own ICs, and may offer design and/or manufacturing (foundry) services to other companies (the latter often to fabless companies). In the foundry model, fabless companies (like Nvidia) only design and sell ICs and outsource all manufacturing to pure play foundries such as TSMC. These foundries may offer IC design services.

Packaging

[edit]

The earliest integrated circuits were packaged in ceramic flat packs, which continued to be used by the military for many years due to their reliability and compact size. Commercial packaging rapidly shifted to the dual in-line package (DIP) — first in ceramic, later in plastic, typically a cresol–formaldehyde–novolac resin.

In the 1980s, the pin count of VLSI circuits exceeded the practical limit of DIP packaging, leading to the adoption of pin grid array (PGA) and leadless chip carrier (LCC) packages. Surface-mount technology (SMT) emerged in the early 1980s and gained popularity by the late 1980s, offering finer lead pitch and using leads formed as either gull-wing or J-lead. A common example is the small-outline integrated circuit (SOIC) package — which occupies about 30–50% less board area than an equivalent DIP and is typically 70% thinner — featuring gull-wing leads extending from its two long sides with a standard lead spacing of 0.050 inches.

By the late 1990s, plastic quad flat pack (PQFP) and thin small-outline package (TSOP) designs became the most common for high pin-count devices, though PGA packages remain in use for high-performance microprocessors.

Ball grid array (BGA) packaging has existed since the 1970s. The flip-chip BGA (FCBGA), developed in the 1990s, enables much higher pin counts than most other package types. In an FCBGA, the die is mounted upside-down and connected to the package balls through a substrate similar to a printed circuit board, rather than by bonding wires. This design allows an array of input/output (I/O) connections — called Area-I/O — to be distributed across the entire die instead of being limited to its edges. While BGA devices eliminate the need for a dedicated socket, they are significantly more difficult to replace if they fail.

Intel transitioned away from PGA to land grid array (LGA) and BGA beginning in 2004, with the last PGA socket released in 2014 for mobile platforms. As of 2018[update], AMD uses PGA packages on mainstream desktop processors,[79] BGA packages on mobile processors,[80] and high-end desktop and server microprocessors use LGA packages.[81]

Electrical signals leaving the die must pass through the material electrically connecting the die to the package, through the conductive traces (paths) in the package, through the leads connecting the package to the conductive traces on the printed circuit board. The materials and structures used in the path these electrical signals must travel have very different electrical properties, compared to those that travel to different parts of the same die. As a result, they require special design techniques to ensure the signals are not corrupted, and much more electric power than signals confined to the die itself.

When multiple dies are put in one package, the result is a system in package, abbreviated SiP. A multi-chip module (MCM), is created by combining multiple dies on a small substrate often made of ceramic. The distinction between a large MCM and a small printed circuit board is sometimes fuzzy.

Packaged integrated circuits are usually large enough to include identifying information. Four common sections are the manufacturer's name or logo, the part number, a part production batch number and serial number, and a four-digit date-code to identify when the chip was manufactured. Extremely small surface-mount technology parts often bear only a number used in a manufacturer's lookup table to find the integrated circuit's characteristics.

The manufacturing date is commonly represented as a two-digit year followed by a two-digit week code, such that a part bearing the code 8341 was manufactured in week 41 of 1983, or approximately in October 1983.

Intellectual property

[edit]The possibility of copying by photographing each layer of an integrated circuit and preparing photomasks for its production on the basis of the photographs obtained is a reason for the introduction of legislation for the protection of layout designs. The US Semiconductor Chip Protection Act of 1984 established intellectual property protection for photomasks used to produce integrated circuits.[82]

A diplomatic conference held at Washington, D.C., in 1989 adopted a Treaty on Intellectual Property in Respect of Integrated Circuits,[83] also called the Washington Treaty or IPIC Treaty. The treaty is currently not in force, but was partially integrated into the TRIPS agreement.[84]

There are several United States patents connected to the integrated circuit, which include patents by J.S. Kilby US3,138,743, US3,261,081, US3,434,015 and by R.F. Stewart US3,138,747.

National laws protecting IC layout designs have been adopted in a number of countries, including Japan,[85] the EC,[86] the UK, Australia, and Korea. The UK enacted the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, c. 48, § 213, after it initially took the position that its copyright law fully protected chip topographies. See British Leyland Motor Corp. v. Armstrong Patents Co.

Criticisms of inadequacy of the UK copyright approach as perceived by the US chip industry are summarized in further chip rights developments.[87]

Australia passed the Circuit Layouts Act of 1989 as a sui generis form of chip protection.[88] Korea passed the Act Concerning the Layout-Design of Semiconductor Integrated Circuits in 1992.[89]

Generations

[edit]In the early days of simple integrated circuits, the technology's large scale limited each chip to only a few transistors, and the low degree of integration meant the design process was relatively simple. Manufacturing yields were also quite low by today's standards. As metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) technology progressed, the size of individual transistors shrank rapidly. By the 1980s, millions of MOS transistors could be placed on one chip,[90] and good designs required thorough planning, giving rise to the field of electronic design automation, or EDA. Some SSI and MSI chips, like discrete transistors, are still mass-produced, both to maintain old equipment and build new devices that require only a few gates. The 7400 series of TTL chips, for example, has become a de facto standard and remains in production.

| Acronym | Name | Year | Transistor count[91] | Logic gates number[92] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSI | small-scale integration | 1964 | 1 to 10 | 1 to 12 |

| MSI | medium-scale integration | 1968 | 10 to 500 | 13 to 99 |

| LSI | large-scale integration | 1971 | 500 to 20 000 | 100 to 9999 |

| VLSI | very large-scale integration | 1980 | 20 000 to 1 000 000 | 10 000 to 99 999 |

| ULSI | ultra-large-scale integration | 1984 | 1 000 000 and more | 100 000 and more |

Small-scale integration (SSI)

[edit]

The first integrated circuits contained only a few transistors. Early digital circuits containing tens of transistors provided a few logic gates, and early linear ICs such as the Plessey SL201 or the Philips TAA320 had as few as two transistors. The number of transistors in an integrated circuit has increased dramatically since then. The term "large scale integration" (LSI) was first used by IBM scientist Rolf Landauer when describing the theoretical concept;[93] that term gave rise to the terms "small-scale integration" (SSI), "medium-scale integration" (MSI), "very-large-scale integration" (VLSI), and "ultra-large-scale integration" (ULSI). The early integrated circuits were SSI.

SSI circuits were crucial to early aerospace projects, and aerospace projects helped inspire development of the technology. Both the Minuteman missile and Apollo program needed lightweight digital computers for their inertial guidance systems. Although the Apollo Guidance Computer led and motivated integrated-circuit technology,[94] it was the Minuteman missile that forced it into mass-production. The Minuteman missile program and various other United States Navy programs accounted for the total $4 million integrated circuit market in 1962, and by 1968, U.S. Government spending on space and defense still accounted for 37% of the $312 million total production.

The demand by the U.S. Government supported the nascent integrated circuit market until costs fell enough to allow IC firms to penetrate the industrial market and eventually the consumer market. The average price per integrated circuit dropped from $50 in 1962 to $2.33 in 1968.[95] Integrated circuits began to appear in consumer products by the turn of the 1970s decade. A typical application was FM inter-carrier sound processing in television receivers.

The first application MOS chips were small-scale integration (SSI) chips.[96] Following Mohamed M. Atalla's proposal of the MOS integrated circuit chip in 1960,[97] the earliest experimental MOS chip to be fabricated was a 16-transistor chip built by Fred Heiman and Steven Hofstein at RCA in 1962.[36] The first practical application of MOS SSI chips was for NASA satellites.[96]

Medium-scale integration (MSI)

[edit]The next step in the development of integrated circuits introduced devices which contained hundreds of transistors on each chip, called "medium-scale integration" (MSI).

MOSFET scaling technology made it possible to build high-density chips.[31] By 1964, MOS chips had reached higher transistor density and lower manufacturing costs than bipolar chips.[38]

In 1964, Frank Wanlass demonstrated a single-chip 16-bit shift register he designed, with a then-incredible 120 MOS transistors on a single chip.[96][98] The same year, General Microelectronics introduced the first commercial MOS integrated circuit chip, consisting of 120 p-channel MOS transistors.[37] It was a 20-bit shift register, developed by Robert Norman[36] and Frank Wanlass.[99][100] MOS chips further increased in complexity at a rate predicted by Moore's law, leading to chips with hundreds of MOSFETs on a chip by the late 1960s.[38]

Large-scale integration (LSI)

[edit]Further development, driven by the same MOSFET scaling technology and economic factors, led to "large-scale integration" (LSI) by the mid-1970s, with tens of thousands of transistors per chip.[101]

The masks used to process and manufacture SSI, MSI and early LSI and VLSI devices (such as the microprocessors of the early 1970s) were mostly created by hand, often using Rubylith-tape or similar.[102] For large or complex ICs (such as memories or processors), this was often done by specially hired professionals in charge of circuit layout, placed under the supervision of a team of engineers, who would also, along with the circuit designers, inspect and verify the correctness and completeness of each mask.

Integrated circuits such as 1K-bit RAMs, calculator chips, and the first microprocessors, that began to be manufactured in moderate quantities in the early 1970s, had under 4,000 transistors. True LSI circuits, approaching 10,000 transistors, began to be produced around 1974, for computer main memories and second-generation microprocessors.

Very-large-scale integration (VLSI)

[edit]

"Very-large-scale integration" (VLSI) is a development that started with hundreds of thousands of transistors in the early 1980s. As of 2023, maximum transistor counts continue to grow beyond 5.3 trillion transistors per chip.

Multiple developments were required to achieve this increased density. Manufacturers moved to smaller MOSFET design rules and cleaner fabrication facilities. The path of process improvements was summarized by the International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors (ITRS), which has since been succeeded by the International Roadmap for Devices and Systems (IRDS). Electronic design tools improved, making it practical to finish designs in a reasonable time. The more energy-efficient CMOS replaced NMOS and PMOS, avoiding a prohibitive increase in power consumption. The complexity and density of modern VLSI devices made it no longer feasible to check the masks or do the original design by hand. Instead, engineers use EDA tools to perform most functional verification work.[103]

In 1986, one-megabit random-access memory (RAM) chips were introduced, containing more than one million transistors. Microprocessor chips passed the million-transistor mark in 1989, and the billion-transistor mark in 2005.[104] The trend continues largely unabated, with chips introduced in 2007 containing tens of billions of memory transistors.[105]

ULSI, WSI, SoC and 3D-IC

[edit]To reflect the continuing increase in complexity, the term ULSI ("ultra-large-scale integration") was introduced for chips containing more than one million transistors.[106] Wafer-scale integration (WSI) is a technique for creating very large integrated circuits by using an entire silicon wafer to fabricate a single "super-chip." By combining large size with reduced packaging, WSI offered the potential for significantly lower costs in certain applications, most notably massively parallel supercomputers. The term itself was derived from Very-Large-Scale Integration (VLSI), which represented the state of the art at the time WSI was under development.[107][108]

A system-on-a-chip (SoC or SOC) is an integrated circuit in which all the components needed for a computer or other system are included on a single chip. The design of such a device can be complex and costly, and whilst performance benefits can be had from integrating all needed components on one die, the cost of licensing and developing a one-die machine still outweigh having separate devices. With appropriate licensing, these drawbacks are offset by lower manufacturing and assembly costs and by a greatly reduced power budget: because signals among the components are kept on-die, much less power is required (see Packaging).[109] Further, signal sources and destinations are physically closer on die, reducing the length of wiring and therefore latency, transmission power costs and waste heat from communication between modules on the same chip. This has led to an exploration of so-called Network-on-Chip (NoC) devices, which apply system-on-chip design methodologies to digital communication networks as opposed to traditional bus architectures.

A three-dimensional integrated circuit (3D-IC) has two or more layers of active electronic components that are integrated both vertically and horizontally into a single circuit. Communication between layers uses on-die signaling, so power consumption is much lower than in equivalent separate circuits. Judicious use of short vertical wires can substantially reduce overall wire length for faster operation.[110]

Silicon labeling and graffiti

[edit]To allow identification during production, most silicon chips will have a serial number in one corner. It is also common to add the manufacturer's logo. Ever since ICs were created, some chip designers have used the silicon surface area for surreptitious, non-functional images or words. These artistic additions, often created with great attention to detail, showcase the designers' creativity and add a touch of personality to otherwise utilitarian components. These are sometimes referred to as chip art, silicon art, silicon graffiti or silicon doodling.[111]

ICs and IC families

[edit]- The 555 timer IC

- The Operational amplifier

- 7400-series integrated circuits

- 4000-series integrated circuits, the CMOS counterpart to the 7400 series (see also: 74HC00 series)

- Intel 4004, generally regarded as the first commercially available microprocessor, which led to the 8008, the famous 8080 CPU, the 8086, 8088 (used in the original IBM PC), and the fully-backward compatible (with the 8088/8086) 80286, 80386/i386, i486, etc.

- The MOS Technology 6502 and Zilog Z80 microprocessors, used in many home computers of the early 1980s

- The Motorola 6800 series of computer-related chips, leading to the 68000 and 88000 series (the 68000 series was very successful and was used in the Apple Lisa and pre-PowerPC-based Macintosh, Commodore Amiga, Atari ST/TT/Falcon030, and NeXT families of computers, along with many models of workstations and servers from many manufacturers in the 80s, along with many other systems and devices)

- The LM-series of analog integrated circuits

See also

[edit]- Central processing unit

- Chip carrier

- CHIPS and Science Act

- Chipset

- Czochralski method

- Dark silicon

- Ion implantation

- Integrated injection logic

- Integrated passive devices

- Interconnect bottleneck

- Heat generation in integrated circuits

- High-temperature operating life

- Microelectronics

- Monolithic microwave integrated circuit

- Multi-threshold CMOS

- Silicon–germanium

- Sound chip

- SPICE

- Thermal simulations for integrated circuits

- Hybrot

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The basics of microchips". ASML.

- ^ "Integrated circuit (IC)". JEDEC.

- ^ Wylie, Andrew (2009). "The first monolithic integrated circuits". Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

Nowadays when people say 'integrated circuit' they usually mean a monolithic IC, where the entire circuit is constructed in a single piece of silicon.

- ^ Horowitz, Paul; Hill, Winfield (1989). The Art of Electronics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-521-37095-0.

Integrated circuits, which have largely replaced circuits constructed from discrete transistors, are themselves merely arrays of transistors and other components built from a single chip of semiconductor material.

- ^ a b c Rostky, George. "Micromodules: the ultimate package". EE Times. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ "The RCA Micromodule". Vintage Computer Chip Collectibles, Memorabilia & Jewelry. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Dummer, G.W.A.; Robertson, J. Mackenzie (16 May 2014). American Microelectronics Data Annual 1964–65. Elsevier. pp. 392–397, 405–406. ISBN 978-1-4831-8549-1.

- ^ "The Chip That Jack Built Changed the World". ti.com. 9 September 1997. Archived from the original on 18 April 2000.

- ^ US Patent 3138743, Kilby, Jack S., "Miniaturized Electronic Circuits", published 23 June 1964

- ^ Winston, Brian (1998). Media Technology and Society: A History: From the Telegraph to the Internet. Routledge. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-415-14230-4.

- ^ "Texas Instruments – 1961 First IC-based computer". Ti.com. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2000". NobelPrize.org. 10 October 2000.

- ^ a b c "Integrated circuits". NASA. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ a b "1959: Practical Monolithic Integrated Circuit Concept Patented". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ a b US2802760A, Lincoln, Derick & Frosch, Carl J., "Oxidation of semiconductive surfaces for controlled diffusion", issued 13 August 1957

- ^ a b Frosch, C. J.; Derick, L (1957). "Surface Protection and Selective Masking during Diffusion in Silicon". Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 104 (9): 547. doi:10.1149/1.2428650.

- ^ a b Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 120. ISBN 9783540342588.

- ^ Fuller, C. S.; Ditzenberger, J. A. (1 July 1953). "Diffusion of Lithium into Germanium and Silicon". Physical Review. 91 (1): 193. Bibcode:1953PhRv...91..193F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.91.193. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Fuller, C. S.; Struthers, J. D.; Ditzenberger, J. A.; Wolfstirn, K. B. (15 March 1954). "Diffusivity and Solubility of Copper in Germanium". Physical Review. 93 (6): 1182–1189. Bibcode:1954PhRv...93.1182F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.93.1182. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Fuller, C. S.; Ditzenberger, J. A. (1 May 1956). "Diffusion of Donor and Acceptor Elements in Silicon". Journal of Applied Physics. 27 (5): 544–553. Bibcode:1956JAP....27..544F. doi:10.1063/1.1722419. ISSN 0021-8979.

- ^ Fuller, C. S.; Whelan, J. M. (1 August 1958). "Diffusion, solubility, and electrical behavior of copper in gallium arsenide". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 6 (2): 173–177. Bibcode:1958JPCS....6..173F. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(58)90091-X. ISSN 0022-3697.

- ^ Miller, R. C.; Savage, A. (1 December 1956). "Diffusion of Aluminum in Single Crystal Silicon". Journal of Applied Physics. 27 (12): 1430–1432. Bibcode:1956JAP....27.1430M. doi:10.1063/1.1722283. ISSN 0021-8979.

- ^ Hall, Eldon C. (1996). Journey to the Moon: The History of the Apollo Guidance Computer. Library of Flight. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-56347-185-8. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ "Computer Pioneers – James L. Buie". IEEE Computer Society. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b "The Texas Instruments TMX 1795: the (almost) first, forgotten microprocessor". Ken Shirriff's blog. 25 October 1970.

- ^ Kuo, Yue (1 January 2013). "Thin Film Transistor Technology—Past, Present, and Future" (PDF). The Electrochemical Society Interface. 22 (1): 55–61. Bibcode:2013ECSIn..22a..55K. doi:10.1149/2.F06131if.

- ^ Huff, Howard; Riordan, Michael (1 September 2007). "Frosch and Derick: Fifty Years Later (Foreword)". The Electrochemical Society Interface. 16 (3): 29. doi:10.1149/2.F02073IF. ISSN 1064-8208.

- ^ Kahng, Dawon (1961). "Silicon-Silicon Dioxide Surface Device". Technical Memorandum of Bell Laboratories: 583–596. doi:10.1142/9789814503464_0076. ISBN 978-981-02-0209-5.

{{cite journal}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. p. 321. ISBN 978-3-540-34258-8.

- ^ Ligenza, J.R.; Spitzer, W.G. (1960). "The mechanisms for silicon oxidation in steam and oxygen". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 14: 131–136. Bibcode:1960JPCS...14..131L. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(60)90219-5.

- ^ a b Laws, David (4 December 2013). "Who Invented the Transistor?". Computer History Museum.

- ^ Bassett, Ross Knox (2002). To the Digital Age: Research Labs, Start-up Companies, and the Rise of MOS Technology. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 53–4. ISBN 978-0-8018-6809-2.

- ^ Bassett, Ross Knox (2007). To the Digital Age: Research Labs, Start-up Companies, and the Rise of MOS Technology. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 9780801886393.

- ^ "Milestones:First Semiconductor Integrated Circuit (IC), 1958". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Milestones:List of IEEE Milestones – Engineering and Technology History Wiki". ethw.org. 9 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Tortoise of Transistors Wins the Race – CHM Revolution". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ a b "1964 – First Commercial MOS IC Introduced". Computer History Museum.

- ^ a b c d Shirriff, Ken (30 August 2016). "The Surprising Story of the First Microprocessors". IEEE Spectrum. 53 (9). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: 48–54. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.2016.7551353. S2CID 32003640.

- ^ "1968: Silicon Gate Technology Developed for ICs". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "1968: Silicon Gate Technology Developed for ICs". The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Hittinger, William C. (1973). "Metal–Oxide–Semiconductor Technology". Scientific American. 229 (2): 48–59. Bibcode:1973SciAm.229b..48H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0873-48. JSTOR 24923169.

- ^ Kanellos, Michael (11 February 2003). "Moore's Law to roll on for another decade". CNET.

- ^ Davari, Bijan; Dennard, Robert H.; Shahidi, Ghavam G. (1995). "CMOS scaling for high performance and low power-the next ten years" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. Vol. 83, no. 4. pp. 595–606. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ "Qualcomm and Samsung Collaborate on 10nm Process Technology for the Latest Snapdragon 835 Mobile Processor". news.samsung.com. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Inside Pascal: NVIDIA's Newest Computing Platform". 5 April 2016.. 15,300,000,000 transistors in 610 mm2.

- ^ "International Roadmap for Devices and Systems" (PDF). IEEE. 2016.

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Physics 2009, Nobel Foundation, 6 October 2009, retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ Fujita, H. (1997). A decade of MEMS and its future. Tenth Annual International Workshop on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems. doi:10.1109/MEMSYS.1997.581729.

- ^ Narasimha, A.; et al. (2008). "A 40-Gb/s QSFP optoelectronic transceiver in a 0.13 µm CMOS silicon-on-insulator technology". Proceedings of the Optical Fiber Communication Conference (OFC): OMK7.

- ^ "Optical chipmaker focuses on high-performance computing". 7 April 2022.

- ^ Birkholz, M.; Mai, A.; Wenger, C.; Meliani, C.; Scholz, R. (2016). "Technology modules from micro- and nano-electronics for the life sciences". WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotech. 8 (3): 355–377. doi:10.1002/wnan.1367. PMID 26391194.

- ^ Graham, Anthony H. D.; Robbins, Jon; Bowen, Chris R.; Taylor, John (2011). "Commercialisation of CMOS Integrated Circuit Technology in Multi-Electrode Arrays for Neuroscience and Cell-Based Biosensors". Sensors. 11 (5): 4943–4971. Bibcode:2011Senso..11.4943G. doi:10.3390/s110504943. PMC 3231360. PMID 22163884.

- ^ Or-Bach, Zvi (23 December 2013). "Why SOI is the Future Technology of Semiconductors". semimd.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.. 2013.

- ^ "Samsung's Eight-Stack Flash Shows up in Apple's iPhone 4". Siliconica. 13 September 2010.

- ^ Yamatake Corporation (2002). "Spherical semiconductor radio temperature sensor". Nature Interface. 7: 58–59. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009.

- ^ Takeda, Nobuo, MEMS applications of Ball Semiconductor Technology (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2015

- ^ "Advanced Packaging".

- ^ "2.5D". Semiconductor Engineering.

- ^ "3D ICs". Semiconductor Engineering.

- ^ "Chiplet". WikiChip. 28 February 2021.

- ^ "To Keep Pace With Moore's Law, Chipmakers Turn to 'Chiplets'". Wired. 11 June 2018.

- ^ Schodt, Christopher (16 April 2019). "This is the year of the CPU 'chiplet'". Engadget.

- ^ "Building Power Electronics with Microscopic Plumbing Could Save Enormous Amounts of Money - IEEE Spectrum".

- ^ "Startup shrinks Peltier cooler, puts it in the chip package". 10 January 2008.

- ^ "Wire Bond Vs. Flip Chip Packaging | Semiconductor Digest". 10 December 2016.

- ^ LaPedus, Mark (16 April 2015). "FinFET Rollout Slower Than Expected". Semiconductor Engineering.

- ^ Basu, Joydeep (9 October 2019). "From Design to Tape-out in SCL 180 nm CMOS Integrated Circuit Fabrication Technology". IETE Journal of Education. 60 (2): 51–64. arXiv:1908.10674. doi:10.1080/09747338.2019.1657787. S2CID 201657819.

- ^ "About the EDA Industry". Electronic Design Automation Consortium. Archived from the original on 2 August 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ Gray, Paul R.; Hurst, Paul J.; Lewis, Stephen H.; Meyer, Robert G. (2009). Analysis and Design of Analog Integrated Circuits. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-24599-6.

- ^ Rabaey, Jan M.; Chandrakasan, Anantha; Nikolic, Borivoje (2003). Digital Integrated Circuits (2nd ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-090996-1.

- ^ Baker, Jacob (2008). CMOS: Mixed-Signal Circuit Design. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-29026-2.

- ^ "Stratix 10 Device Overview" (PDF). Altera. 12 December 2015.

- ^ Nathawad, L.; Zargari, M.; Samavati, H.; Mehta, S.; Kheirkhaki, A.; Chen, P.; Gong, K.; Vakili-Amini, B.; Hwang, J.; Chen, M.; Terrovitis, M.; Kaczynski, B.; Limotyrakis, S.; Mack, M.; Gan, H.; Lee, M.; Abdollahi-Alibeik, B.; Baytekin, B.; Onodera, K.; Mendis, S.; Chang, A.; Jen, S.; Su, D.; Wooley, B. "20.2: A Dual-band CMOS MIMO Radio SoC for IEEE 802.11n Wireless LAN" (PDF). IEEE Entity Web Hosting. IEEE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "16nm/14nm FinFETs: Enabling The New Electronics Frontier". electronicdesign.com. 17 January 2013.

- ^ Mead, Carver; Conway, Lynn (1991). Introduction to VLSI systems. Addison Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-201-04358-7. OCLC 634332043.

- ^ "Hot Work Ultrasonic Bonding – A Method Of Facilitating Metal Flow By Restoration Processes", Proc. 20th IEEE Electronic Components Conf., Washington, D.C., May 1970, pp. 549–556.

- ^ Chafkin (15 May 2020). "TSMC to build 5nm fab in arizona, set to come online in 2024". Anandtech. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020.

- ^ "145 series ICs (in Russian)". Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ Moammer, Khalid (16 September 2016). "AMD Zen CPU & AM4 Socket Pictured, Launching February 2017 – PGA Design With 1331 Pins Confirmed". Wccftech. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "Ryzen 5 2500U – AMD – WikiChip". wikichip.org. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Ung, Gordon Mah (30 May 2017). "AMD's 'TR4' Threadripper CPU socket is gigantic". PCWorld. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "Federal Statutory Protection for Mask Works" (PDF). United States Copyright Office. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Washington Treaty on Intellectual Property in Respect of Integrated Circuits". www.wipo.int.

- ^ On 1 January 1995, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) (Annex 1C to the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement), went into force. Part II, section 6 of TRIPs protects semiconductor chip products and was the basis for Presidential Proclamation No. 6780, 23 March 1995, under SCPA § 902(a)(2), extending protection to all present and future WTO members.

- ^ Japan was the first country to enact its own version of the SCPA, the Japanese "Act Concerning the Circuit Layout of a Semiconductor Integrated Circuit" of 1985.

- ^ In 1986 the EC promulgated a directive requiring its members to adopt national legislation for the protection of semiconductor topographies. Council Directive 1987/54/EEC of 16 December 1986 on the Legal Protection of Topographies of Semiconductor Products, art. 1(1)(b), 1987 O.J. (L 24) 36.

- ^ Stern, Richard (1985). "MicroLaw". IEEE Micro. 5 (4): 90–92. doi:10.1109/MM.1985.304489.

- ^ Radomsky, Leon (2000). "Sixteen Years after the Passage of the U.S. Semiconductor Chip Protection Act: Is International Protection Working". Berkeley Technology Law Journal. 15: 1069. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Kukkonen, Carl A. III (1997–1998). "The Need to Abolish Registration for Integrated Circuit Topographies under Trips". IDEA: The Journal of Law and Technology. 38: 126. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Clarke, Peter (14 October 2005). "Intel enters billion-transistor processor era". EE Times. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011.

- ^ Dalmau, M. "Les Microprocesseurs" (PDF). IUT de Bayonne. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Bulletin de la Société fribourgeoise des sciences naturelles, Volumes 62 à 63 (in French). 1973.

- ^ Safir, Ruben (March 2015). "System on Chip – Integrated Circuits". NYLXS Journal. ISBN 9781312995512.

- ^ Mindell, David A. (2008). Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13497-2.

- ^ Ginzberg, Eli (1976). Economic impact of large public programs: the NASA Experience. Olympus Publishing Company. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-913420-68-3.

- ^ a b c Johnstone, Bob (1999). We were burning: Japanese entrepreneurs and the forging of the electronic age. Basic Books. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0-465-09118-8.

- ^ Moskowitz, Sanford L. (2016). Advanced Materials Innovation: Managing Global Technology in the 21st century. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 165–167. ISBN 9780470508923.

- ^ Boysel, Lee (12 October 2007). "Making Your First Million (and other tips for aspiring entrepreneurs)". U. Mich. EECS Presentation / ECE Recordings.

- ^ Kilby, J. S. (2007). "Miniaturized electronic circuits [US Patent No. 3,138, 743]". IEEE Solid-State Circuits Society Newsletter. 12 (2): 44–54. doi:10.1109/N-SSC.2007.4785580.

- ^ US Patent 3138743

- ^ Hittinger, William C. (1973). "Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Technology". Scientific American. 229 (2): 48–59. Bibcode:1973SciAm.229b..48H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0873-48. JSTOR 24923169.

- ^ Kanellos, Michael (16 January 2002). "Intel's Accidental Revolution". CNET.

- ^ "Engineering for Systems Using Large Scale Integration". International Workshop on Managing Requirements Knowledge, Dec. 9 1968 to Dec. 11 1968, San Francisco. IEEE Computer Society. p. 867. doi:10.1109/AFIPS.1968.93.

- ^ Clarke, Peter (14 October 2005). "Intel enters billion-transistor processor era". EETimes.com. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Samsung First to Mass Produce 16Gb NAND Flash Memory". phys.org. 30 April 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Meindl, J.D. (1984). "Ultra-large scale integration". IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices. 31 (11): 1555–1561. Bibcode:1984ITED...31.1555M. doi:10.1109/T-ED.1984.21752. S2CID 19237178.

- ^ US patent 4866501, Shanefield, Daniel, "Wafer scale integration", published 1985

- ^ Edwards, Benj (14 November 2022). "Hungry for AI? New supercomputer contains 16 dinner-plate-size chips". Ars Technica.

- ^ US patent 6816750, Klaas, Jeff, "System-on-a-chip", published 2000

- ^ Topol, A.W.; Tulipe, D.C.La; Shi, L; et., al (2006). "Three-dimensional integrated circuits". IBM Journal of Research and Development. 50 (4.5): 491–506. doi:10.1147/rd.504.0491. S2CID 18432328.

- ^ The Secret Art of Chip Graffiti IEEE Spectrum article on chip artwork, by H. Goldstein, Volume: 39, Issue: 3, Mar 2002, pp. 50–55.

Further reading

[edit]- Veendrick, H.J.M. (2025). Nanometer CMOS ICs, from Basics to ASICs. Springer. ISBN 978-3-031-64248-7. OCLC 1463505655.

- Baker, R.J. (2010). CMOS: Circuit Design, Layout, and Simulation (3rd ed.). Wiley-IEEE. ISBN 978-0-470-88132-3. OCLC 699889340.

- Marsh, Stephen P. (2006). Practical MMIC design. Artech House. ISBN 978-1-59693-036-0. OCLC 1261968369.

- Camenzind, Hans (2005). Designing Analog Chips (PDF). Virtual Bookworm. ISBN 978-1-58939-718-7. OCLC 926613209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2017.

Hans Camenzind invented the 555 timer

- Hodges, David; Jackson, Horace; Saleh, Resve (2003). Analysis and Design of Digital Integrated Circuits. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-228365-5. OCLC 840380650.

- Rabaey, J.M.; Chandrakasan, A.; Nikolic, B. (2003). Digital Integrated Circuits (2nd ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-090996-1. OCLC 893541089.

- Mead, Carver; Conway, Lynn (1991). Introduction to VLSI systems. Addison Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-201-04358-7. OCLC 634332043.

External links

[edit]- The first monolithic integrated circuits

- A large chart listing ICs by generic number including access to most of the datasheets for the parts.

- The History of the Integrated Circuit

.jpg/250px-NXP_PCF8577C_LCD_driver_with_I²C_(Colour_Corrected).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-NXP_PCF8577C_LCD_driver_with_I²C_(Colour_Corrected).jpg)