Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Oranienburg

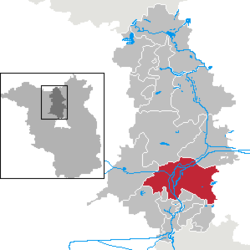

View on WikipediaOranienburg (German: [oˈʁaːniənˌbʊʁk] ⓘ) is a town in Brandenburg, Germany. It is the capital of the district of Oberhavel.

Key Information

Geography

[edit]Oranienburg is on the banks of the River Havel, 35 km north of the centre of Berlin.

Division of the town

[edit]Oranienburg consists of nine districts:

- Friedrichsthal

- Germendorf

- Lehnitz

- Malz

- Oranienburg

- Sachsenhausen

- Schmachtenhagen

- Wensickendorf

- Zehlendorf

History

[edit]

Originally named Bötzow, the town of Oranienburg dates from the 12th century and was first mentioned in 1216. Margrave Albert the Bear (ruled 1157–1170) allegedly ordered the construction of a castle on the banks of the Havel. Around the castle stood a settlement of traders and craftsmen.

In 1646, Friedrich Wilhelm I of Brandenburg married Louise Henriette of Orange-Nassau (German: Oranien-Nassau). She was so attracted by the town of Bötzow that her husband presented the entire region to her. The princess ordered the construction of a new castle in the Dutch style and called it Oranienburg or Schloss Oranienburg. In 1653 the town of Bötzow was renamed Oranienburg.

Silvio Gesell, the founder of Freiwirtschaft ("free economy"), lived in Oranienburg between 1911 and 1915, publishing his magazine, Der Physiocrat. He returned to the town in 1927 and lived there until his death in 1930. The town remained a center of the "free economy" movement until the Nazi régime outlawed it in 1933, and many of Gesell's followers ended up as prisoners in the town's concentration camp.[citation needed]

The Oranienburg concentration camp (established in March 1933) was among the earliest of the Nazis concentration camps. In 1936, the Sachsenhausen concentration camp on the outskirts of Oranienburg replaced it; there 200,000 people were interned over the nine years that the Nazis operated it. Approximately 22,000 people died at the camp before the liberation of the camp by the Soviet Red Army in 1945. Thereafter the site reopened in August 1945 as "Soviet Special Camp 7". A further 12,000 people (mostly Nazis not awaiting trial) died under the Soviets before the Special Camp closed in 1950. Their remains were not discovered until the 1990s.[citation needed]

Oranienburg became the center of Nazi Germany's nuclear-energy project because it was the location of the Auergesellschaft Oranienburg Plant, Germany's uranium production facility; the town also had an armaments hub, aircraft plant, and railway junction, all of military importance. According to military historian Antony Beevor, Stalin's desire to acquire the nuclear facility motivated him to launch the Battle for Berlin[3] of April–May 1945. It has been claimed that the pre-emptive destruction of these nuclear facilities by the USAAF Eighth Air Force on 15 March 1945 aimed to prevent them from falling into Soviet hands.[4]

On 23 April 1945, during the Battle of Berlin, troops of the 1st Belorussian Front of the Red Army captured Oranienburg.

Between 1949 and 1990, Oranienburg was part of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

Due to its heavy bombing, Oranienburg is the "most dangerous town in Germany"; it is the only town in Germany which pursues a systematic search for unexploded ordnance (UXO) based on postwar aerial photos and magnetic or radar underground measurements for metal. By 2017 about 200 had been disposed of, and 350 to 400 were estimated to remain.[5] It is estimated[by whom?] that the search and disposal will continue throughout the rest of the century. In one case 12,000 residents had to be evacuated. The federal government does not finance the removal of foreign UXO.[6][need quotation to verify] [7]

Public institutions

[edit]The Zehlendorf transmission facility, a large facility for radio broadcasting in longwave, medium wave and FM-range, was located near Oranienburg, at Zehlendorf.

Transport

[edit]The town is served by the Berlin Northern Railway and provide a direct connection to Rostock.

Demography

[edit]-

Development of population since 1875 within the current boundaries (blue line: population; dotted line: comparison to population development of Brandenburg state; grey background: time of Nazi rule; red background: time of communist rule)

-

Recent population development and projections (population pevelopment before 2011 census (blue line); recent population development according to the census in Germany in 2011 (blue bordered line); official projections for 2005–2030 (yellow line); for 2020–2030 (green line); for 2017–2030 (scarlet line)

Oranienburg: Population development within the current boundaries (2020)[8] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Notable people

[edit]

- Friedrich Ludwig Dulon (1769–1826), flautist and composer

- Walther Bothe (1891–1957), physicist and Nobel laureate

- Carl Gustav Hempel (1905–1997), philosopher

- W. Michael Blumenthal (born 1926), business leader, economist and political adviser

- Bernd Eichwurzel (born 1964), rower, Olympic champion

- Alexander Walke (born 1983), footballer

- Marcus Mlynikowski (born 1992), footballer

- Silvio Gesell, lived between 1911 and 1915 and between 1927 and his death in 1930

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Landkreis Oberhavel Wahl der Bürgermeisterin / des Bürgermeisters Archived 2021-07-09 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Alle politisch selbständigen Gemeinden mit ausgewählten Merkmalen am 31.12.2023" (in German). Federal Statistical Office of Germany. 28 October 2024. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ Antony Beevor (2002). Berlin: The Downfall 1945. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-88695-5. Preface p. xxxiv

- ^ Richard G. Davis, Bombing the European Axis Powers: A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945. Alabama: Air University Press, 2006, page 518, 523.

- ^ "Frankfurt WW2 bomb: Mass evacuation completed". BBC News. 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (10 March 2015). "Bombenjäger". ARD.de. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Ralph Caspers (2019-09-17). "Explosives Erbe - Blindgänger unter unseren Füßen". Quarks (in German). www.ardmediathek.de. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- ^ Detailed data sources are to be found in the Wikimedia Commons. Population Projection Brandenburg at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ "Partnerstädte". oranienburg.de (in German). Oranienburg. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

External links

[edit]- Official website

(in German)

(in German)

Oranienburg

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Administrative Structure

Oranienburg is a town situated in the state of Brandenburg, Germany, approximately 35 kilometers northwest of central Berlin.[1] It lies at geographic coordinates 52°45′16″N 13°14′13″E, along the banks of the Havel River, within a landscape featuring lakes, canals, meadows, and woodlands.[6][7] The town covers an area of 163.7 square kilometers and had an estimated population of 49,122 residents as of 2024.[2] Administratively, Oranienburg serves as the seat of the Oberhavel district (Landkreis Oberhavel), one of the 14 rural districts in Brandenburg.[8] As a Stadt (town), it functions as an independent municipality within this district, with its own local government headed by a mayor and town council. The town is subdivided into nine Ortsteile (local districts): Friedrichsthal, Germendorf, Lehnitz, Malz, Oranienburg (core area), Sachsenhausen, Schmachtenhagen, Wensickendorf, and Zehlendorf.[9] These divisions reflect historical villages incorporated into the modern municipality, supporting decentralized administration for local services and community governance.[9]

Physical Features and Climate

Oranienburg lies on the banks of the Havel River in Brandenburg's Oberhavel district, within the flat expanses of the North German Lowlands shaped by glacial activity during the Pleistocene.[10][11] The terrain is predominantly level, with minimal elevation changes typical of the region's post-glacial morphology, including sandy glacial soils and proximity to lakes and waterways.[10] The town's average elevation stands at 43 meters above sea level, reflecting its lowland setting.[12] Soils in the surrounding area are chiefly sandy and sandy-loamy, classified as lower quality for intensive agriculture due to their drainage properties and nutrient retention.[13] The climate of Oranienburg is classified as temperate continental, featuring cold winters and mild summers influenced by its inland position. Average annual precipitation measures approximately 678 mm, distributed relatively evenly throughout the year with moderate seasonal variation.[14] Temperatures typically range from a low of -1.7°C in winter months to a high of 24.4°C in summer, with extremes occasionally reaching -10°C or 30.6°C.[15] The Havel River moderates local microclimates, contributing to higher humidity levels near water bodies, though the broader area experiences overcast conditions about 47% of the time during summer.[16]History

Medieval Foundations and Early Development

The region encompassing modern Oranienburg was initially settled by West Slavic tribes during the early Middle Ages, part of the broader Polabian Slavic presence in the Havel River area east of the Elbe, where agrarian villages and fortified sites developed amid forested lowlands.[17] These Slavic communities, known collectively as Hevelli or similar groups under loose tribal structures, engaged in subsistence farming, fishing along the Havel, and limited trade routes, with no centralized urban centers but rather dispersed grod (fortified settlements) vulnerable to incursions from expanding Frankish and later German powers. Archaeological traces, including pottery and wooden structures, indicate continuity from the 8th-10th centuries, though specific Slavic nomenclature for the site—likely Bothzowe—reflects linguistic roots tied to local waterways or terrain, predating Germanic toponymy.[18] German eastward expansion under the Ascanian dynasty marked the transition to documented medieval foundations, with margraves establishing control over Slavic-held territories in Brandenburg by the late 12th century. Around 1200, an Ascanian castle was constructed on an island in the Havel River as a strategic bulwark for controlling river crossings and securing the frontier against remnant Slavic resistance, featuring earthen ramparts and wooden fortifications later reinforced through multiple phases.[19] This Burg Bötzow, germanized from the Slavic precursor, served as an administrative and military outpost, facilitating the Ostsiedlung—the influx of Saxon, Flemish, and other settlers who introduced manorial agriculture, water mills, and proto-urban markets. Excavations from 1997-1999 uncovered medieval building layers confirming iterative expansions, underscoring the site's role in consolidating margravial authority amid ongoing hybridization of Slavic-German populations.[19] The settlement of Bötzow received its earliest surviving documentary mention in 1216, in records tied to Ascanian land grants and ecclesiastical tithes, signaling formalized integration into the Margraviate of Brandenburg's feudal network.[20] Early development proceeded through the 13th century with population growth driven by agrarian clearance and riverine trade in timber, grain, and amber, though constrained by the region's glacial sands and frequent flooding; by mid-century, embryonic town features emerged, including a parish church dedicated to Saint Nicholas by 1230, reflecting Christianization efforts post-Slavic paganism.[20] No full municipal charter survives from this era, but the castle-town nexus fostered defensive self-organization, with Bötzow functioning as a local hub under margravial oversight rather than independent burgher autonomy, setting precedents for later urban privileges amid the dynasty's internal divisions and external threats from Pomeranian rivals.[17]Early Modern Period and Prussian Integration

During the early modern period, Oranienburg, formerly known as Bötzow, emerged as a significant residence within the Electorate of Brandenburg following the devastations of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). Under Elector Frederick William, known as the Great Elector, who ruled from 1640 to 1688, the area saw reconstruction efforts to bolster Hohenzollern authority.[21] The Great Elector married Louise Henriette of Orange-Nassau in 1646, and in 1651 she initiated the construction of a Baroque palace on the site of an earlier medieval fortress, transforming it into a Dutch-influenced summer residence.[22] Construction of Schloss Oranienburg proceeded from 1651 to 1655, marking it as the oldest Baroque palace in the Margraviate of Brandenburg.[23] The palace symbolized the cultural and political aspirations of the Brandenburg court, incorporating elements like the Orange Hall and Porcelain Chamber, the latter displaying over 5,000 East Asian porcelain pieces to project regal splendor.[24] Following Louise Henriette's death in 1667, the residence saw limited use until Frederick William's son, Frederick III (Elector from 1688, crowned King Frederick I in Prussia in 1701), expanded and refurbished it for representational purposes.[24] This elevation of Brandenburg to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701 integrated Oranienburg more firmly into the emerging absolutist state, with the palace serving as a venue for diplomatic displays of the Hohenzollerns' rising power.[23] In July 1709, Frederick I hosted a notable summit at the palace, where he met with Frederick IV of Denmark and Frederick Augustus I of Saxony (Elector Augustus the Strong) from July 9 to 11 to forge an alliance against Sweden's Charles XII during the Great Northern War.[24] The event underscored the palace's role in Prussian foreign policy. Later, King Frederick William I (r. 1713–1740) pragmatically traded 151 porcelain items from the chamber in 1717 for 600 soldiers, reflecting the militaristic priorities that defined Prussian state-building.[24] By the mid-18th century, under Prince August William (1722–1758), brother of Frederick II the Great, the palace enjoyed a revival as a cultural center before declining in prominence.[23] These developments cemented Oranienburg's place within the Prussian administrative and symbolic framework, transitioning from a local estate to a marker of monarchical consolidation.[25]Industrial Growth in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries

During the early 19th century, Oranienburg emerged as a site for innovative milling operations, with the establishment of Prussia's first American-style mill along the Havel River, leveraging hydraulic power and advanced grain processing techniques introduced by trained engineers.[26] This development marked an initial shift toward mechanized production, capitalizing on the town's waterway access for transportation and energy. By the mid-19th century, chemical processing gained prominence, particularly through the work of chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge at a local factory focused on coal tar distillation. Runge's experiments there advanced the isolation of key compounds like aniline precursors, laying groundwork for synthetic dye production and fertilizers such as "German guano" derived from industrial byproducts, which spurred applications in agriculture and manufacturing.[27] These activities aligned with broader Prussian industrial expansion, drawing on coal resources and proximity to Berlin's markets. At the turn of the 20th century, Oranienburg hosted a cluster of large-scale chemical plants supplying Berlin's gas lighting sector, where vast quantities of coal tar were refined into tar oil, benzene, and other aromatics essential for fuels, solvents, and early petrochemicals.[28] This concentration reflected strategic locational advantages, including rail and river links, fostering employment in heavy industry and positioning the town as a peripheral hub for Berlin's urban-industrial demands before the disruptions of the interwar period.Nazi Era: Rise to Power and Initial Concentration Camp

The National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) cultivated a local presence in Oranienburg during the late 1920s and early 1930s, drawing from veterans of right-wing paramilitary groups who joined the party and its Sturmabteilung (SA) auxiliary. Figures such as SA-Standartenführer Werner Schulze-Wechsungen, an NSDAP member since 1925, exemplified this continuity, participating in actions like a 1932 SA raid on a communist settlement to disrupt left-wing organizing in the town's industrial districts. Such confrontations with the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and its Red Front Fighters' League paramilitary helped the Nazis erode opponents' street-level control, capitalizing on unemployment from the Great Depression—which hit Oranienburg's chemical and metalworking sectors hard—and widespread disillusionment with the Weimar coalition government.[29] Adolf Hitler's appointment as Chancellor on January 30, 1933, followed by the Reichstag fire on February 27, 1933, enabled the Nazis to deploy the Reichstag Fire Decree, suspending habeas corpus and press freedoms to justify mass arrests of suspected subversives. In Oranienburg, SA Standarte 208—under leaders including Sturmbannführer Werner Schäfer—seized the initiative, establishing a concentration camp on March 21, 1933, coinciding with the national "Day of Potsdam" pomp aligning Nazi rule with Prussian militarism. The site, a repurposed brewery on Breitenstrasse in the town center, functioned as one of Prussia's inaugural state-run detention facilities, exemplifying the proliferation of SA "wild camps" for extrajudicial internment.[4][29] Primarily targeting political adversaries, the camp held KPD and Social Democratic Party (SPD) members, trade unionists, centrists, and right-wing nonconformists, alongside about 50 Jewish youths; prominent detainees included anarchist Erich Mühsam. Roughly 3,000 individuals cycled through between March 1933 and July 1934, with occupancy rising from 97 prisoners shortly after opening to a peak of 911 in August 1933 before declining to 271 by June 1934.[4][29] Inmates endured severe maltreatment, including routine beatings, torture sessions, nutritional deprivation, and absence of medical treatment, compounded by coerced labor on local road and rail projects. Jewish prisoners faced segregated confinement in a "Jews’ company" with escalated violence. At least 16 deaths occurred from these abuses, notably Mühsam's torture-induced demise on July 11, 1934. SA guards staged the site as a propaganda "model camp," inviting journalists and filming newsreels to depict orderly "protective custody" and political re-education, masking the underlying terror.[4][29] Operations halted in July 1934 during the Night of the Long Knives, which decimated SA command structures and prompted Heinrich Himmler's SS to monopolize the concentration camp system. Surviving prisoners transferred to SS facilities like Lichtenburg on July 13, 1934, while the Oranienburg site deactivated by 1935, paving the way for the purpose-built Sachsenhausen camp on adjacent grounds in 1936. This episode underscored the causal role of SA intimidation in the Nazis' local power consolidation, transitioning from ad hoc violence to institutionalized repression.[4][29]Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp Operations and Atrocities (1936-1945)

Sachsenhausen concentration camp, located on the outskirts of Oranienburg, was established by the SS in July 1936 as the primary detention facility for the Berlin region, succeeding an earlier provisional camp in the town center opened in March 1933. Construction began that summer using forced labor from prisoners transferred from Emsland camps, with the first detainees primarily comprising political opponents of the Nazi regime, such as communists and social democrats. Under SS administration, the camp served as a model for other facilities, emphasizing strict discipline, forced labor, and terror to suppress perceived enemies.[5][30] The camp's prisoner population expanded rapidly, with over 200,000 individuals passing through between 1936 and 1945, including political prisoners marked with red triangles, criminals with green, Jehovah's Witnesses with purple, homosexuals with pink, and Jews with yellow stars or badges after 1938. By 1938, the influx included large numbers of Jews arrested during Kristallnacht, alongside asocials and other targeted groups; Soviet prisoners of war arrived in significant numbers from 1941, facing immediate mass executions. Daily life involved grueling routines of roll calls lasting hours in harsh weather, minimal rations leading to starvation, and brutal punishments by SS guards and kapos, fostering a system designed to break inmates physically and psychologically.[5][31] Forced labor became central to operations, with prisoners deployed in quarries, brickworks, and later armaments production for firms like Heinkel and Siemens, often under lethal conditions that prioritized output over survival. Medical experiments conducted in the camp infirmary from the late 1930s included tests on epidemic jaundice vaccines using deliberate infections, mustard gas exposure simulations, and studies on tuberculosis and typhus, resulting in numerous deaths without consent or anesthesia. These procedures, overseen by SS physicians, aimed to advance military medicine but exemplified the regime's disregard for human life, with survivors suffering long-term disabilities.[32][33] Atrocities escalated with the construction of "Station Z" in 1943, a dedicated killing facility equipped with a shooting trench, gas chamber using Zyklon B, and four crematoria ovens for disposing of bodies, where an estimated 4,000 Soviet POWs and commissars were executed in 1941 alone by genickshots to the neck. Executions targeted condemned prisoners, including those from other camps, with methods involving mass shootings, hangings, and lethal injections; arbitrary murders by SS personnel were routine, often under the guise of maintaining order. Overall, at least 30,000 prisoners perished from executions, disease, starvation, and overwork, though exact figures remain uncertain due to incomplete records destroyed by the SS.[5][34] As Allied forces advanced, the camp held around 37,000 prisoners by early 1945, prompting death marches in April that claimed thousands more lives; Soviet troops liberated the site on April 22, 1945, finding approximately 3,000 emaciated survivors amid evidence of recent killings and cremations. The SS commandants, including figures like Hermann Baranowski (1936-1938) and Anton Kaindl (1943-1945), oversaw this progression from political internment to industrialized murder, with postwar trials convicting several for their roles in the systematic abuses.[35][36]Post-War Soviet Special Camp and Early GDR Period

Following the liberation of Sachsenhausen concentration camp by Soviet forces on April 22, 1945, the site was repurposed by the Soviet occupation authorities as NKVD Special Camp No. 7, operational from August 1945 until its closure in March 1950.[37] This facility formed part of a network of ten special camps established across the Soviet Occupation Zone to facilitate denazification through preventive detention, though it also served broader political repression objectives, interning not only Nazi functionaries but also suspected opponents, Wehrmacht officers, and Soviet citizens such as POWs and forced laborers.[37] Approximately 60,000 individuals passed through the camp, including around 30,000 classified as the "special contingent" comprising SS members, Gestapo personnel, Nazi Party youth affiliates, and other political adversaries; over 16,000 convicted by Soviet military tribunals; about 6,500 German military officers; and more than 7,000 Soviet nationals.[37] Conditions within the camp were marked by severe overcrowding in former Nazi barracks, deficient sanitation, insufficient rations, and lack of medical care, with no permitted external communication, earning them designation as "silence camps" distinct from labor facilities.[37] These factors led to approximately 12,000 deaths, primarily from starvation, disease, and exhaustion, with mortality peaking during the "Winter of Hunger" in 1946-1947; a 2010 register compiled by the Sachsenhausen Memorial documents 11,890 specific fatalities.[37] Unlike Nazi extermination policies, deaths resulted from systemic neglect rather than deliberate mass killing, though the internment encompassed many without Nazi ties, including those accused on flimsy grounds such as anti-Soviet utterances, highlighting the camps' role in consolidating Soviet dominance.[38] Upon closure, around 1,900 internees and 5,100 convicts were released, while 4,800 were transferred to East German judicial authorities, where some faced subsequent show trials under the newly formed German Democratic Republic (GDR) from October 1949 onward.[37] The site itself remained under Soviet military administration post-1950, restricting local access and development in Oranienburg during the early GDR years, as the town integrated into the socialist economy through nationalized industries and agricultural reforms, though specific local repression echoed the special camp era via ongoing denazification proceedings.[37] Mass graves from the period, containing thousands of remains, were later exhumed and commemorated after German reunification, underscoring the underreported scale of Soviet-era internment fatalities across the zone's camps, where up to 42,000 died in total from similar causes.[38]GDR Industrialization and Repression

Following the establishment of the German Democratic Republic in 1949, Oranienburg's economy underwent state-directed nationalization and expansion as part of the GDR's centralized Five-Year Plans emphasizing heavy industry and chemicals. Private firms were transformed into Volkseigene Betriebe (VEBs, or people's own enterprises), with Oranienburg hosting around 35 such entities by the 1950s-1980s, focusing on metal processing, pharmaceuticals, and specialty chemicals. Key operations included the VEB Kaltwalzwerk Oranienburg, which produced cold-rolled steel products at its facility on Kremmener Straße until 1989, serving as a cornerstone of local manufacturing; the VEB Chemisch-Pharmazeutisches Werk Oranienburg, which manufactured preservatives and pharmaceuticals from former pre-war sites; and the VEB Rußwerk Oranienburg, specializing in gas black (carbon black) for industrial applications.[39][40] These VEBs integrated into national supply chains, contributing to the GDR's output in materials essential for machinery, construction, and exports to Comecon partners, though inefficiencies from bureaucratic planning often led to shortages and underutilization.[41] The regime enforced industrialization through mandatory production quotas, ideological indoctrination via Socialist brigades, and SED party oversight in workplaces, where workers faced penalties for failing targets tied to "building socialism." Repression was systemic, with the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) maintaining surveillance networks in factories to monitor and neutralize perceived sabotage or dissent, including informant infiltration and arbitrary arrests.[42] In Oranienburg, as in other industrial locales, Stasi operations extended to local facilities, reflecting the broader pattern where economic coercion—such as job loss, imprisonment, or forced relocation—ensured compliance amid the GDR's political monoculture.[42] This control suppressed independent trade unions, replacing them with state-aligned FDGB structures, and contributed to labor unrest echoes from the 1953 uprising, though Oranienburg-specific protests remained localized and swiftly quashed by security forces. By the 1980s, underlying economic stagnation in these VEBs fueled quiet discontent, culminating in the regime's collapse without major violent crackdowns in the town.Reunification and Contemporary Challenges

Following the reunification of Germany on October 3, 1990, Oranienburg transitioned from the centrally planned economy of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) to a market-oriented system, resulting in the closure or privatization of inefficient state-owned enterprises. The VEB Kaltwalzwerk Oranienburg, a major cold rolling mill operational until 1989, was largely dismantled in the post-Wende period, contributing to significant job losses amid broader deindustrialization in eastern Germany.[43] In response, local authorities repurposed portions of the industrial site into the Oranienwerk cultural and creative hub, exemplifying efforts to diversify beyond heavy industry.[43] To address urban decay, Oranienburg launched comprehensive inner-city renovation initiatives in the early 1990s, focusing on infrastructure upgrades, beautification, and enhanced livability, which by 2021 had transformed the town center into a more vibrant residential and commercial district.[44] Proximity to Berlin facilitated commuting and attracted some investment, mitigating some effects of regional economic stagnation, though unemployment peaked alongside eastern Germany's average of around 20% in the early 1990s.[45] Demographic pressures persisted, with out-migration of younger residents leading to population stagnation or decline, aging of the populace, and strain on public services—patterns common in Brandenburg's post-reunification towns.[46] Contemporary challenges include the persistent hazard of approximately 250 unexploded World War II bombs embedded in the soil, remnants of the March 15, 1945, Allied bombing that devastated the town and necessitates costly, ongoing disposal operations by authorities.[47] Additionally, sustaining the Sachsenhausen Memorial amid fluctuating federal funding has required local advocacy to preserve historical accountability without over-reliance on tourism.[48] These issues underscore Oranienburg's adaptation to structural economic shifts while grappling with legacy burdens and demographic sustainability.Demographics

Population Trends and Statistics

Oranienburg's population trends reflect broader historical and economic shifts in the region, with long-term growth punctuated by periods of stagnation during the 20th century's authoritarian regimes and acceleration post-reunification as a Berlin commuter hub. The town's current boundaries encompass an area of 163.7 km², yielding a population density of about 300 inhabitants per square kilometer as of recent estimates.[2] Following the 2011 census, which revised prior overestimates downward, the population dipped to around 45,000 in the mid-2010s before resuming upward trajectory. On December 31, 2013, Oranienburg recorded 42,727 residents. By 2024, this had risen to an estimated 49,122, reflecting an annual growth rate of 1.2% from 2022 to 2024, driven by inbound migration from Berlin and economic opportunities in the area.[49][2] In early 2025, the population surpassed the 50,000 mark for the first time, exceeding earlier projections and underscoring the town's appeal amid regional suburban expansion. Official forecasts from around 2021 anticipated reaching approximately 50,100 by 2040, but actual developments indicate potentially stronger sustained growth.[49][50]Ethnic and Social Composition

Oranienburg's ethnic composition is characterized by a strong predominance of ethnic Germans, aligning with the low diversity typical of eastern Brandenburg, where Slavic minorities like the Sorbs represent a negligible fraction of the total population. As of 2023, foreigners comprised 5.19% of residents, numbering 2,535 individuals out of approximately 48,844 inhabitants, with males making up 53.14% of this subgroup and females 46.86%.[51] This proportion exceeds the district average in Oberhavel, where the foreign resident share stood at around 3.9% to 6.0% in recent years, but remains far below national figures, reflecting limited large-scale immigration and a historical reliance on internal German resettlement after World War II.[52][53] The broader population with migration background—encompassing naturalized citizens and descendants of immigrants—is estimated to be modest, consistent with Brandenburg's overall rate of under 15% as of the early 2010s, though precise municipal data for Oranienburg indicate no significant deviation from this pattern amid ongoing population growth driven by domestic inflows.[54] Socially, the town's structure retains imprints of its GDR-era industrialization, with a notable working-class element tied to sectors like manufacturing and chemicals, though post-reunification shifts have fostered a commuter economy linking residents to Berlin's service and tech opportunities. Full-time workers earned an average gross monthly salary of €3,767 (or €45,204 annually) as of mid-2025, below the national median but supported by low unemployment rates of 5.2% recorded in 2018.[55][56] Educational infrastructure, including multiple primary and secondary schools, underpins a mixed socioeconomic profile, with ongoing demographic expansion—reaching over 50,000 residents by April 2025—altering traditional structures through younger families and inbound migration from other German regions.[57]Economy

Industrial Base and Key Sectors

Oranienburg maintains a diversified industrial base rooted in manufacturing and logistics, with strengths in specialized production that leverage the town's proximity to Berlin and access to skilled labor in Brandenburg. The local economy features a mix of large employers and small-to-medium enterprises (Mittelstand), contributing to the Oberhavel region's status as one of Brandenburg's stronger industrial districts. Key drivers include export-oriented firms in high-tech materials and healthcare products, supported by modern infrastructure and regional clusters in chemicals and life sciences.[58] The pharmaceuticals sector represents a cornerstone, exemplified by Takeda GmbH's manufacturing facility in Oranienburg, which produces active pharmaceutical ingredients and finished drugs such as pantoprazole (a proton pump inhibitor) and vortioxetine (an antidepressant branded as Trintellix). This site integrates into Takeda's global supply chain, employing hundreds and underscoring the town's role in biopharmaceutical production amid Germany's emphasis on resilient domestic manufacturing.[59][60] Plastics processing and polymer refinement form another vital pillar, led by ORAFOL Europe GmbH, headquartered in Oranienburg with extensive production of self-adhesive specialty foils, reflective films for traffic safety, and technical laminates. The company reported €883 million in revenue for 2024 and employs approximately 2,600 people locally, bolstered by a €100 million investment announced in March 2025 for a new production hall to expand polymer capabilities. Additional firms like Plastimat Oranienburg GmbH reinforce this focus on custom plastics for automotive and industrial applications.[61][62][63] Logistics emerges as a complementary sector, driven by Oranienburg's strategic location along major transport corridors. The REWE Group's distribution center in the southern industrial park handles grocery supply chains for northern Germany, while parcel services like Hermes utilize the area's warehousing for e-commerce fulfillment, capitalizing on efficient rail and highway links to Berlin and beyond. These operations employ logistics specialists and support just-in-time delivery models amid rising online retail demands.[64] Supporting industries include metalworking and chemicals, tracing back to early 20th-century factories that supplied Berlin's infrastructure, though contemporary emphasis has shifted toward sustainable and innovative applications within regional clusters. Overall, these sectors sustain employment for thousands, with manufacturing firms prioritizing R&D in materials science and biotech to align with EU green transition goals.[65][28]Employment, Unemployment, and Economic Shifts Post-Reunification

Following German reunification in 1990, Oranienburg, like other East German localities, experienced a rapid economic transition from centrally planned socialism to a market economy, marked by the closure or privatization of inefficient state-owned enterprises (VEBs) that had dominated local industry, such as those in light manufacturing and processing. This led to a sharp surge in unemployment across Brandenburg, with the state's rate rising dramatically from near-zero official figures under the GDR (which masked underemployment) to averages exceeding 10% by 1991 as industrial output collapsed.[66] In the Oberhavel district encompassing Oranienburg, unemployment reflected broader eastern trends but benefited from proximity to Berlin, fostering commuting to western jobs; rates peaked amid the structural adjustment, reaching 12.4% in 2008 amid the global financial crisis and lingering privatization effects.[67] By 2016, the rate had halved to 6.8%, approaching western German levels through labor market reforms, retraining programs, and inbound investment.[67] Recent figures show further decline, with Oberhavel's overall unemployment at 5.3% as of late 2023, supported by a skilled workforce and regional stability.[68] Economic shifts emphasized diversification beyond legacy sectors, with Oranienburg emerging as a regional growth core alongside Hennigsdorf and Velten, hosting over 1,700 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by the 2010s.[64] Company numbers expanded across all size categories from 2006 to 2017, driven by clusters in plastics and chemistry (e.g., ORAFOL Europe GmbH, Kryolan GmbH), logistics and mobility (e.g., REWE Group, Hermes), pharmaceuticals (e.g., TAKEDA GmbH), and metal processing.[64] This reorientation capitalized on Berlin's orbit for export-oriented manufacturing and services, reducing reliance on heavy industry while integrating global firms, though challenges like skill mismatches persisted in absorbing former GDR workers.[69] Employment increasingly involved cross-border commuting, with many residents accessing Berlin's service and tech sectors, contributing to net job growth despite initial losses estimated in the thousands locally from VEB liquidations.[58]Government and Public Administration

Local Governance Structure

Oranienburg's local government operates under the municipal code of the state of Brandenburg, featuring a directly elected full-time mayor (hauptamtlicher Bürgermeister) as the chief executive responsible for administration, budget execution, and representation of the town. The mayor is elected by popular vote for an eight-year term and chairs the Stadtverordnetenversammlung, the elected representative assembly that serves as the legislative body, approving budgets, ordinances, and major policies.[70][71] The Stadtverordnetenversammlung consists of 36 members elected every five years through proportional representation, with seats allocated based on party lists and voter turnout; the most recent election occurred on June 9, 2024, resulting in representation from major parties including CDU, SPD, and AfD, alongside smaller groups.[72][73] The assembly forms specialized committees for areas such as finance, urban planning, social affairs, and environmental protection to deliberate on specific issues before full council votes.[74] As of October 19, 2025, the mayor is Jennifer Collin-Feeder of the SPD, who won a runoff election with approximately 58% of the vote against AfD candidate Anja Waschkau, succeeding independent Alexander Laesicke whose term ended after the September 28, 2025, first round yielded no absolute majority.[75][76] The administrative apparatus under the mayor includes departments for citizen services, public order, education, and economic development, coordinated from the town hall at Schloßplatz 1.[77] While the town handles core local functions, certain responsibilities like waste management and secondary education fall to the Oberhavel district administration.[8]Public Institutions and Services

Oranienburg's public institutions encompass municipal administrative services, educational facilities, healthcare providers, and safety agencies, primarily coordinated through the city administration and the Oberhavel district. The Bürgerdienste department handles citizen services such as resident registration, civil documents, and public order matters, with support from the central Bürgeramt accessible via phone for inquiries and referrals to specialized offices.[78] The city's administrative structure includes four main depts: the mayor's office for oversight and safety; finances and central services for HR and budgeting; urban development for planning and infrastructure; and citizen services for education and social welfare.[79] Education is provided through a network of 21 kindergartens (Kitas), 12 primary schools (Grundschulen), two special needs schools (Förderschulen), and nine secondary schools, including the Gymnasium Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge and the Jean-Clermont-Schule.[80] The town also hosts the Hochschule der Polizei Brandenburg, a state police academy offering training programs.[80] Healthcare services center on the Klinik Oranienburg, part of Oberhavel Kliniken GmbH, which maintains 203 beds across six departments including anesthesiology, surgery, gynecology, and internal medicine, handling 8,567 inpatient and 16,856 outpatient cases annually.[81] [82] The facility includes a social service unit advising on rehabilitation, long-term care, and disability benefits.[83] Public safety is ensured by the Polizeiinspektion Oberhavel at Germendorfer Allee 17, operating 24/7 for emergencies via the statewide 110 line and providing local policing.[84] The Feuerwehr Oranienburg combines professional and volunteer units at Julius-Leber-Straße 25, responding to fires, accidents, and disasters with training aligned to state standards.[85] Social services, managed district-wide, include welfare assistance (Sozialhilfe) through the Oberhavel Landkreis office and community counseling at the Bürgerzentrum for family, consumer, and tenant issues, supplemented by hospital-based support for post-discharge care.Infrastructure and Transport

Road and Rail Networks

Oranienburg's rail infrastructure centers on Oranienburg station, which opened in 1877 and lies on the Berlin Northern Railway line. The town benefits from multiple regional and long-distance services, including the S1 line of the Berlin S-Bahn, which runs from Oranienburg to Berlin-Wannsee in a 20-minute interval takt.[86] Regionalbahn connections include RB 20 to Potsdam Hauptbahnhof, RB 32 to Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER), RB 12 from Templin via Oranienburg to Berlin-Lichtenberg, and RB 27 (Heidekrautbahn) from Berlin-Karow to Oranienburg.[86] Longer routes feature Regional-Express RE 5 from Stralsund or Rostock through Oranienburg to Berlin Südkreuz, and InterCity services from Rostock via Oranienburg to Dresden, operating every two hours.[86] The road network provides strong links to Berlin and beyond, with direct access to the A10 Berliner Ring autobahn, which connects to the A2 toward Hannover, A9 to Munich, and A24 to Hamburg.[86] The A111 autobahn links Oranienburg to Berlin-Reinickendorf via the Oranienburg interchange (Kreuz Oranienburg), integrating with the A10 and B96. Federal highway B96 passes through Oranienburg, extending from Zittau via Berlin to Stralsund and Sassnitz on Rügen, while B273 connects Potsdam to Bernau through the town.[86] Local land roads such as L 211 to Mühlenbeck and L 191 to Sommerfeld support intra-regional travel.[86]Urban Planning and Connectivity to Berlin

Oranienburg's urban planning post-reunification has prioritized inner-city revitalization and residential expansion to support growing population and economic integration with Berlin. In 1991, the Innenstadt district was designated a sanierungsgebiet under Brandenburg's urban development funding program, targeting structural decay from the East German era through renovations and adaptive reuse. The Integrated Urban Development Concept (INSEK), established in 2014, provides a strategic framework for balanced growth, currently under revision to address accelerated demographic pressures.[87] Key initiatives include the Weiße Stadt residential extension, a 17-hectare project for roughly 500 units initiated via a 2013 international design competition. This development extends the 1930s-era neighborhood grid across Walther-Bothe-Straße, incorporating varied building alignments and open spaces to foster urban diversity, noise mitigation, and links to the city center eastward and Oranienburg Channel westward.[88] Oranienburg's proximity—11 kilometers north of Berlin's boundary—enhances its role as a commuter hub, with the S1 S-Bahn line offering direct, frequent service from Oranienburg station to Berlin centers like Hauptbahnhof in about 29 minutes over 28 kilometers.[89][90] Road connectivity supports this via the B96 federal highway routing southbound to Berlin and access to the A10 ring motorway at Kreuz Oranienburg, which intersects the A111 from Berlin's northwest.[91] These links facilitate efficient daily travel, underpinning Oranienburg's suburban expansion while preserving historical fabric amid modern infrastructure demands.[92]Culture and Landmarks

Historical Architecture and Sites

Schloss Oranienburg, the town's defining historical landmark, originated as a rural mansion constructed between 1651 and 1655 for Louise Henriette of Orange-Nassau, the first wife of Elector Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia.[3] This early structure served as a summer residence, reflecting Dutch influences from Louise Henriette's heritage, before its expansion into a Baroque palace.[3] The palace complex, including its gardens, symbolizes the Electorate of Brandenburg's rising prestige in the late 17th century.[3] Baroque reconstruction began in 1689 under architects Arnold Nering and later Eosander von Göthe, drawing stylistic elements from Italian and French models to create one of the Mark Brandenburg's earliest and most significant palaces.[18] The design features symmetrical facades, grand halls, and integrated landscape gardens typical of absolutist architecture, with the palace positioned along the Havel River for scenic prominence.[3] Associated structures include the Orangerie in the palace park, used historically for exotic plant cultivation, and the Schlosshafen, a harbor facilitating access and trade.[93] Today, the palace functions as the Schlossmuseum Oranienburg, preserving interiors and hosting exhibits on regional history, including Prussian-era artifacts and temporary displays.[3] The surrounding Baroque gardens, laid out contemporaneously, feature formal parterres and avenues that complement the architectural ensemble, though some elements have been restored post-World War II damage.[3] A monument to Louise Henriette stands nearby, commemorating her role in the site's development.[94] Oranienburg's old town retains medieval foundations dating to the 13th century, when the settlement was known as Bötzow, but surviving architecture primarily clusters around the palace district rather than extensive half-timbered or Gothic structures.[95] The palace's influence extended to urban planning, shaping the adjacent areas into a coordinated Baroque ensemble that integrated residential and ceremonial spaces.[96]Sachsenhausen Memorial and Museums

The Sachsenhausen Memorial and Museum commemorates the site's history as a Nazi concentration camp from 1936 to 1945 and subsequent Soviet special camp from 1945 to 1950. Established in 1961 by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) as the Sachsenhausen National Memorial, it initially focused on anti-fascist resistance narratives, housing a museum in a former camp kitchen building that highlighted communist prisoners while marginalizing other victim groups such as Jews, Jehovah's Witnesses, and political opponents outside the communist framework.[97] This presentation aligned with GDR ideological priorities, which privileged state-approved interpretations over comprehensive victim documentation.[97] Following German reunification, the site underwent significant reconfiguration in 1993 under the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation, expanding to address previously underrepresented aspects including the Soviet Special Camp No. 7, where approximately 60,000 individuals were interned and 12,000 died from starvation, disease, and executions between 1945 and 1950.[98] [37] New exhibits incorporated evidence of mass killings, forced labor, and medical experiments during the Nazi period, with estimates of 30,000 to 50,000 deaths among the over 200,000 prisoners held there, though precise figures remain contested due to incomplete records and varying methodologies.[34] [5] Permanent exhibitions today include dedicated spaces on Jewish prisoners in Barracks 38 and 39 of the "Small Camp," the role of Oranienburg locals in relation to camp operations, and the post-liberation Soviet internment system, supported by archival research such as the "Book of the Dead" for special camp victims.[99] [100] A 2001-2007 overhaul introduced a main exhibition in the former kitchen detailing daily camp operations, prisoner transports, and SS administration, aiming for a more evidence-based portrayal that acknowledges the site's multifaceted history of repression under both Nazi and Soviet regimes.[101] The memorial serves educational purposes, attracting visitors to confront empirical records of totalitarianism, with guided tours emphasizing primary sources over politicized narratives.[102]Local Traditions and Events

Oranienburg hosts several annual events centered on its historical sites and community gatherings, including the Stadtfest, a city festival featuring local performances, markets, and family activities typically held in summer.[103] The Weihnachtsmarkt, or Christmas market, takes place in the town center during Advent, offering traditional German crafts, food stalls with Glühwein and bratwurst, and festive lighting, drawing residents and visitors from the Brandenburg region.[103][104] The Pfingst-Spectaculum, a medieval-themed festival at Schloss Oranienburg park during Pentecost, recreates historical markets with artisan demonstrations, knight spectacles, and period costumes, attracting over 10,000 attendees in recent years.[105] Other recurring events include the Schlossparknacht, an evening open-air concert and cultural night in the castle grounds, and the Spielefest, focused on board games and recreational activities for all ages.[103] Picknick in Weiß, a summer picnic event encouraging white attire, promotes communal dining and live music in public spaces.[103] These gatherings emphasize Oranienburg's blend of Prussian heritage and modern community engagement, with many tied to the Schloss Oranienburg as a venue, though they avoid direct references to the town's darker 20th-century history.[106] Local participation is high, supported by the city's tourism office, but events remain modest in scale compared to Berlin's festivals, reflecting the town's population of approximately 45,000.[106]Notable Individuals

Contributions to Science and Philosophy

Carl Gustav Hempel, born in Oranienburg on January 8, 1905, emerged as a pivotal figure in the philosophy of science, particularly through his advocacy for logical empiricism.[107] He studied mathematics, physics, and philosophy at universities including Göttingen and Berlin before fleeing Nazi Germany in 1937, eventually settling in the United States where he taught at Yale and Princeton.[107] Hempel's seminal contributions include the deductive-nomological model of scientific explanation, which posits that explanations derive from general laws and initial conditions, and the raven paradox, illustrating challenges in inductive confirmation where observing a non-black non-raven seemingly confirms "all ravens are black."[108] These ideas underscored his emphasis on logical rigor in demarcating scientific knowledge from metaphysics, influencing mid-20th-century debates on explanation and confirmation.[107] Walther Bothe, also born in Oranienburg on January 8, 1891, advanced experimental physics through the development of the coincidence method for detecting simultaneous particle events.[109] After studying at the University of Berlin and conducting research under Max Planck, Bothe applied this technique to verify energy conservation in Compton scattering and to investigate cosmic rays, demonstrating their particulate nature via correlations with penetrating radiation.[109] His innovations facilitated precise measurements in nuclear reactions and quantum events, earning him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1954, shared with Max Born, for the coincidence method and related discoveries.[110] Bothe's work bridged classical and quantum paradigms, providing empirical foundations for subsequent particle physics research despite his later involvement in Nazi-era projects.[111]Figures in Arts, Politics, and Labor Movements

Friedrich Ludwig Dülon (1769–1826), a prominent flutist and composer born in Oranienburg on August 14, 1769, achieved fame as a virtuoso despite becoming blind at six weeks old due to medical complications.[112] He began performing publicly as a child, studying under Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and touring extensively across Europe, including performances for Mozart and royalty.[113] Dülon's compositions, primarily for flute, numbered over 100 works, emphasizing technical prowess and improvisation, which established him as a key figure in late 18th-century German music.[114] His autobiography, published in 1807, details his career challenges and successes, underscoring resilience in the arts amid personal adversity.[113] In politics, W. Michael Blumenthal (born January 3, 1926, in Oranienburg) emerged as a significant German-American figure, serving as the 64th United States Secretary of the Treasury from 1977 to 1979 under President Jimmy Carter.[115] Born to a Jewish family, Blumenthal fled Nazi persecution in 1939, spending the war years in Shanghai before emigrating to the United States in 1947, where he naturalized and pursued economics.[116] His career included roles as deputy special representative for trade negotiations and CEO of Bendix Corporation, influencing U.S. economic policy during the late 1970s energy crisis and inflation challenges.[117] Later honored as an honorary citizen of Oranienburg, Blumenthal's trajectory reflects adaptation from wartime displacement to high-level policymaking.[118] Prominent figures from Oranienburg in labor movements are scarce in historical records, with no widely recognized leaders originating from the town who shaped broader German or international union activities. Early 20th-century industrial sites like the Auerwerke employed local workers, but documentation highlights forced labor under Nazi control rather than autonomous labor advocacy.[119] Political prisoners, including communists held in the early Oranienburg camp from 1933, represented leftist opposition but were victims of suppression rather than originating organizers from the locale.[120]International Relations

Twin Towns and Partnerships

Oranienburg maintains official partnerships with five towns, fostering cultural, educational, and economic exchanges through joint events, youth programs, and municipal cooperation. These relationships emphasize mutual support, particularly in post-reunification development for Oranienburg and reconciliation efforts internationally.[121] The partnership with Bagnolet, France, was established in June 1964, making it the longest-standing international link; Bagnolet, located on the eastern edge of Paris in Seine-Saint-Denis, has facilitated exchanges in urban planning and cultural activities. The connection with Mělník, Czech Republic, dates to October 7, 1974; situated about 30 km north of Prague at the confluence of the Vltava and Elbe rivers, it promotes tourism and historical dialogue, including wine festivals and police training collaborations. Domestically, Oranienburg partnered with Hamm in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, in October 1990, shortly after German reunification; Hamm provided early assistance in administrative rebuilding and infrastructure, sustaining active exchanges in education and sports over three decades.[121] The agreement with Vught, Netherlands, began in 2000, focusing on shared historical remembrance—Vught hosts the National Memorial Camp Kamp Vught—and community initiatives like youth delegations and environmental projects. The most recent partnership is with Kfar Yona (also spelled Kfar Jona), Israel, formalized on September 30, 2021; this central district town in the Sharon Plain supports intercultural understanding, including Holocaust education programs and joint commemorations like Zikaron Basalon events involving students from both municipalities.[122]| Partner Town | Country | Established |

|---|---|---|

| Bagnolet | France | June 1964 |

| Mělník | Czech Republic | October 7, 1974 |

| Hamm | Germany | October 1990 [121] |

| Vught | Netherlands | 2000 |

| Kfar Yona | Israel | September 30, 2021 [122] |