Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Libertas

View on Wikipedia| Libertas | |

|---|---|

Goddess of liberty | |

| |

| Symbol | Pileus, rod (vindicta or festuca) |

| Equivalents | |

| Greek | Artemis Eleutheria |

Libertas (Latin for 'liberty' or 'freedom', pronounced [liːˈbɛrt̪aːs̠]) is the Roman goddess and personification of liberty. She became a politicised figure in the late republic. She sometimes also appeared on coins from the imperial period, such as Galba's "Freedom of the People" coins during his short reign after the death of Nero.[1] She is usually portrayed with two accoutrements: the spear; and pileus, a cap commonly worn by freed slaves, which she holds out in her right hand rather than wears on her head.

The Greek equivalent of the goddess Libertas is Eleutheria, the personification of liberty. There are many post-classical depictions of liberty as a person which often retain some of the iconography of the Roman goddess.

Etymology

[edit]The noun lībertās 'freedom', on which the name of the deity is based, is a derivation from Latin līber 'free', stemming from Proto-Italic *leuþero-, and ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *h₁leudʰero- 'belonging to the people', hence 'free'.[2]

Attributes

[edit]Libertas was associated with the pileus, a cap commonly worn by freed slaves:[3]

Among the Romans the cap of felt was the emblem of liberty. When a slave obtained his freedom he had his head shaved, and wore instead of his hair an undyed pileus (πίλεον λευκόν, Diodorus Siculus Exc. Leg. 22 p625, ed. Wess.; Plaut. Amphit. I.1.306; Persius, V.82). Hence the phrase servos ad pileum vocare is a summons to liberty, by which slaves were frequently called upon to take up arms with a promise of liberty (Liv. XXIV.32). "The figure of Liberty on some of the coins of Antoninus Pius, struck A.D. 145, holds this cap in the right hand".[4]

Libertas was also recognized in ancient Rome by the rod (vindicta or festuca),[3] used ceremonially in the act of Manumissio vindicta, Latin for 'freedom by the rod' (emphasis added):

The master brought his slave before the magistratus, and stated the grounds (causa) of the intended manumission. "The lictor of the magistratus laid a rod (festuca) on the head of the slave, accompanied with certain formal words, in which he declared that he was a free man ex Jure Quiritium", that is, "vindicavit in libertatem". The master in the meantime held the slave, and after he had pronounced the words "hunc hominem liberum volo," he turned him round (momento turbinis exit Marcus Dama, Persius, Sat. V.78) and let him go (emisit e manu, or misit manu, Plaut. Capt. II.3.48), whence the general name of the act of manumission. The magistratus then declared him to be free [...][5]

Temples

[edit]The Roman Republic was established simultaneously with the creation of Libertas and is associated with the overthrow of the Tarquin kings. She was worshiped by the Junii, the family of Marcus Junius Brutus.[6] In 238 BC, before the Second Punic War, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus built a temple to Libertas on the Aventine Hill.[7] Census tables were stored inside the temple's atrium. A subsequent temple was built (58–57 BC) on Palatine Hill, another of the Seven hills of Rome, by Publius Clodius Pulcher. By building and consecrating the temple on the site of the former house of then-exiled Cicero, Clodius ensured that the land was legally uninhabitable. Upon his return, Cicero successfully argued that the consecration was invalid and thus managed to reclaim the land and destroy the temple. In 46 BC, the Roman Senate voted to build and dedicate a shrine to Libertas in recognition of Julius Caesar, but no temple was built; instead, a small statue of the goddess stood in the Roman Forum.[8]

Post-classical

[edit]

The goddess Libertas is also depicted on the Great Seal of France, created in 1848. This is the image which later influenced French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi in the creation of his statue of Liberty Enlightening the World.

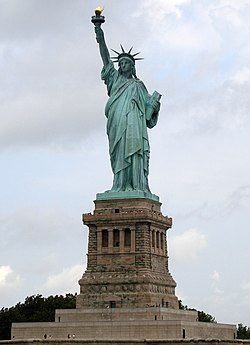

Libertas, along with other Roman goddesses, has served as the inspiration for many modern-day personifications, including the Statue of Liberty on Liberty Island in the United States. According to the National Park Service, the Statue's Roman robe is the main feature that invokes Libertas and the symbol of Liberty from which the statue derives its name.[9]

In addition, money throughout history has borne the name or image of Libertas. As "Liberty", Libertas was depicted on the obverse (heads side) of most coinage in the U.S. into the twentieth century – and the image is still used for the American Gold Eagle gold bullion coin. The University of North Carolina records two instances of private banks in its state depicting Libertas on their banknotes;[10][11] Libertas is depicted on the 5, 10 and 20 Rappen denomination coins of Switzerland.

The symbolic characters Columbia who represents the United States and Marianne, who represents France, the Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World) in New York Harbor, and many other characters and concepts of the modern age were created, and are seen, as embodiments of Libertas.

See also

[edit]- Liber

- Libera (mythology) a goddess in Roman mythology

- Liberty (personification)

- Liberty Leading the People, 1830 painting

References

[edit]- ^ "Roman Coins" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-31. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ de Vaan 2008, p. 338.

- ^ a b Tate, Karen; Olson, Brad (2005). Sacred Places of Goddess: 108 Destinations. CCC Publishing. pp. 360–361. ISBN 1-888729-11-2.

- ^ Yates, James. Entry "Pileus" in William Smith's A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (John Murray, London, 1875).

- ^ Long, George. Entry "Manumission" in William Smith's A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (John Murray, London, 1875).

- ^ The American Catholic Quarterly Review ... Hardy and Mahony. 1880. p. 589.

- ^ Karl Galinsky; Kenneth Lapatin (1 January 2016). Cultural Memories in the Roman Empire. Getty Publications. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-60606-462-7.

- ^ "Libertas". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ "Robe". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 7, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ Howgego, C. J. (1995). Ancient history from coins. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-08993-7. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Bank of Fayetteville one-dollar note, 1855". Archived from the original on 2012-05-24. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

.png/250px-INC-1841-r_Ауреус_Траян_ок._108-110_гг._(реверс).png)

.png)