Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

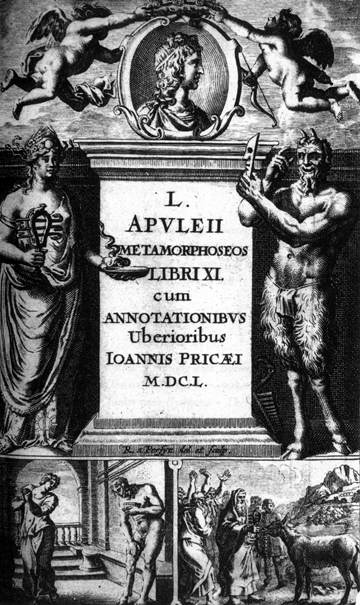

The Golden Ass

View on WikipediaThe Metamorphoses of Apuleius, which Augustine of Hippo referred to as The Golden Ass (Latin: Asinus aureus),[1] is the only ancient Roman novel in Latin to survive in its entirety.[2]

Key Information

The protagonist of the novel is Lucius.[3] At the end of the novel, he is revealed to be from Madaurus,[4] the hometown of Apuleius himself. The plot revolves around the protagonist's curiosity (curiositas) and insatiable desire to see and practice magic. While trying to perform a spell to transform into a bird, he is accidentally transformed into an ass. This leads to a long journey, literal and metaphorical, filled with inset tales. He finally finds salvation through the intervention of the goddess Isis, whose cult he joins.

Origin

[edit]

The date of composition of the Metamorphoses is uncertain. It has variously been considered by scholars as a youthful work preceding Apuleius' Apology of 158–159, or as the climax of his literary career, and perhaps as late as the 170s or 180s.[5] Apuleius adapted the story from a Greek original of which the author's name is said to be an otherwise unknown "Lucius of Patrae", also the name of the lead character and narrator.[6]

This Greek text by Lucius of Patrae has been lost, but there is Lucius or the Ass (Λούκιος ἢ ὄνος, Loukios ē onos), a similar tale of disputed authorship, traditionally attributed to the writer Lucian, a contemporary of Apuleius. This surviving Greek text appears to be an abridgement or epitome of Lucius of Patrae's text.[7]

Manuscripts

[edit]The Metamorphoses has survived in about 40 manuscripts, all or almost all of which are descendants of codex Laurentianus 68.2 (also called F in critical apparatuses), an extant 11th-century manuscript produced in Monte Cassino. Editors of the text have therefore seen it as their goal to apply textual criticism to this particular manuscript, ignoring the rest except for occasional consultation. The text is characterized by a number of non-standard spellings, notably the frequent interchange of the letters b and v.[8]

Plot

[edit]Book One

[edit]The prologue establishes an audience and a speaker, who defines himself by location, education, occupation, and his kinship with the philosophers Plutarch and Sextus of Chaeronea. The narrator journeys to Thessaly on business. On the way, he runs into Aristomenes and an unnamed traveler. The unnamed traveler refuses to believe Aristomenes' story. The narrator insults the unnamed traveler and tells a short story about a sword swallower. He promises Aristomenes a free lunch if he will retell his tale. The narrator believes Aristomenes' tale and becomes more eager to learn about magic. The narrator arrives at Hypata, where he stays with Milo, a friend and miser, and his wife Pamphile. Photis, a serving girl in Milo's household, takes the narrator to the baths, after which the narrator goes to the marketplace. There, he buys some fish and runs into his old friend Pytheas, who is now a market official. Pytheas reveals the narrator's name as Lucius. Pytheas says that Lucius overpaid for the fish and humiliates the fish-monger by trampling on the fish. Lucius returns to Milo's house, hungry and empty-handed. Milo asks Lucius about his life, his friends, and his wanderings, which Lucius grows bored with. Lucius goes to sleep hungry.

Book Two

[edit]The next morning, Lucius meets up with his suspicious aunt Byrrhena in the town, and she brings him home and warns him that Milo's wife is an evil witch who wants to kill Lucius, who is interested in becoming a witch himself. He then returns to Milo's house, where he makes love to Photis. The next day, Lucius goes to his aunt's home for dinner, and there meets Thelyphron, who relates his tale about how witches cut off his nose and ears. After the meal, Lucius drunkenly returns to Milo's house in the dark, where he encounters three robbers, whom he soon slays before retiring to bed.

Book Three

[edit]

The next morning, Lucius is abruptly awoken and arrested for the murder of the three men. He is taken to court, where he is laughed at constantly, and witnesses are brought against him. They are just about to announce his guilt when the widow demands to bring out the dead bodies; but when the three bodies of the murdered men are revealed, they turn out to be puffed-up wineskins. It turns out that it was a prank, played by the town upon Lucius, to celebrate their annual Festival of Laughter. Later that day, Lucius and Photis watch Milo's wife perform her witchcraft and transform herself into a bird. Wishing to do the same, Lucius begs Photis to transform him, but she accidentally turns him into an ass, at which point Photis tells him that the only way for him to return to his human state is to eat a fresh rose. She puts him in the stable for the night and promises to bring him roses in the morning, but during the night Milo's house is raided by a band of thieves, who steal Lucius the ass, load him up with their plunder, and leave with him.

Book Four

[edit]On a break in his journey with the bandits, Lucius the ass trots over to a garden to munch on what seem to be roses (but are actually poisonous rose-laurels) when he is beaten by the gardener and chased by dogs. The thieves reclaim him and he is forced to go along with them; they talk about how their leader Thrasileon has been killed while dressed as a bear. The thieves also kidnap a rich young woman, Charite, who is housed in a cave with Lucius the ass. Charite starts crying, so an elderly woman who is in league with the thieves begins to tell her the story of Cupid and Psyche.

Psyche is the most beautiful woman on earth, and Venus jealously arranges for Psyche's destruction, ordering her son Cupid to arrange for her to fall in love with a worthless wretch. An oracle tells Psyche's parents to expose her on a mountain peak, where she will become the bride of a powerful, monstrous being. Psyche is left on the mountain, and carried away by a gentle wind.

Book Five

[edit]The elderly woman continues telling the story of Cupid and Psyche. Cupid, Venus's son, secretly protects Psyche; Cupid becomes Psyche's mysterious husband, who is invisible to her by day and visits her only at night. Psyche's jealous sisters arouse her curiosity and fear about her husband's identity; Psyche, against Cupid's commands, looks at him by lamplight which wakes Cupid; Cupid abandons Psyche, who wanders in search of him, and takes revenge on her wicked sisters.

Book Six

[edit]The elderly woman finishes telling the story of Cupid and Psyche, as Psyche is forced to perform various tasks for Venus (including an errand to the underworld) with the help of Cupid and an assortment of friendly creatures, and is finally reunited with her husband. Then Jupiter transforms Psyche into a goddess. That is the end of the tale. Lucius the ass and Charite escape from the cave but they are caught by the thieves, and sentenced to death.

Book Seven

[edit]A man appears to the thieves and announces that he is the renowned thief Haemus the Thracian, who suggests that they should not kill the captives but sell them. Haemus later reveals himself secretly to Charite as her fiancé Tlepolemus, and gets all of the thieves drunk. When they are asleep he slays them all. Tlepolemus, Charite and Lucius the ass safely escape back to the town. Once there, the ass is entrusted to a horrid boy who intends to castrate him but the boy is later killed by a she-bear. Enraged, the boy's mother plans to kill the ass.

Book Eight

[edit]A man arrives at the mother's house and announces that Tlepolemus and Charite are dead, caused by the scheming of the evil Thrasillus who wants Charite to marry him. After hearing the news of their master's death, the slaves run away, taking the ass Lucius with them. The large group of travelling slaves is mistaken for a band of robbers and attacked by farmhands of a rich estate. Several other misfortunes befall the travelers until they reach a village. Lucius as the narrator often digresses from the plot in order to recount several scandal-filled stories that he learns of during his journey. Lucius is eventually sold to a gallus priest of Cybele. He is entrusted with carrying the statue of Cybele on his back while he follows the group of priests on their rounds, who perform ecstatic rites in local farmsteads and estates for alms. While engaging in lewd activity with a local boy, the group of priests is discovered by a man in search of a stolen ass who mistakes Lucius' braying for that of his own animal. The priests flee to a new city where they are well received by one of its chief citizens. They are preparing to dine when his cook realizes that the meat that was to be served was stolen by a dog. The cook, at the suggestion of his wife, prepares to kill Lucius in order to serve his meat instead.

Book Nine

[edit]Lucius' untimely escape from the cook coincides with an attack by rabid dogs, and his wild behavior is attributed to their viral bites. The men barricade him in a room until it is decided that he is no longer infected. The band of galli eventually pack up and leave.

The narrative is interrupted by the Tale of the Wife's Tub.

Soon after, the galli are accosted by an armed troop who accuse them of stealing from their village temple, and are subsequently detained (with the treasures returned). Lucius is sold into labor, driving a baker's mill-wheel. Lucius, though bemoaning his labor as an ass, also realizes that this state has allowed him to hear many novel things with his long-ass ears.

The Tale of the Jealous Husband and the Tale of the Fuller's Wife mark a break in the narrative. The theme of the two intervening stories is adultery, and the text appropriately follows with the adultery of the baker's wife and the subsequent murder of the baker.

Lucius the ass is then auctioned off to a farmer. The Tale of the Oppressive Landlord is here told. The farmer duly assaults a legionary who makes advances on his ass, Lucius, but he is found out and jailed.

Book Ten

[edit]Lucius comes into the legionary's possession, and after lodging with a decurion, Lucius recounts the Tale of the Murderous Wife. He is then sold to two brothers, a confectioner and a cook, who treat him kindly. When they go out, Lucius secretly eats his fill of their food. At first a source of vexation, when the ass is discovered to be the one behind the disappearing food it is much laughed at and celebrated.

Again he is sold, and he is taught many amusing tricks. Rumor spreads, and great fame comes to the ass and his master. As it happens, a woman is so enamored with the sideshow ass that she bribes his keeper and takes Lucius the ass to her bed. Lucius is then scheduled to have sex in the arena with a multiple murderess before she is to be eaten by wild beasts; the Tale of the Jealous Wife tells her backstory.

After an enactment of the judgment of Paris, and a brief digression on philosophy and corruption, the time comes for Lucius to make his much-anticipated appearance. At the last moment he decides that copulating with such a wicked woman would be repugnant to him, and, moreover, the wild beasts would likely eat him along with her; and so he runs away to Cenchreae, eventually to nap on the beach.

Book Eleven

[edit]Lucius wakes up in a panic during the first watch of the night. Considering Fate to be done tormenting him, he takes the opportunity to purify himself by seven consecutive immersions in the sea. He then offers a prayer to the Queen of Heaven, for his return to human form, citing all the various names the goddess is known by to people everywhere (Venus, Ceres, Diana, Proserpine, etc.). The Queen of Heaven appears in a vision to him and explains to him how he can be returned to human form by eating the crown of roses that will be held by one of her priests during a religious procession the following day. In return for his redemption, Lucius is expected to be initiated through the Navigium Isidis into Isis' priesthood, Isis being the Queen of Heaven's true name. Lucius follows her instructions and is returned to human form and, at length, initiated into her priesthood.

Lucius is then sent to his ancestral home, Rome, where he continues to worship Isis under the local name, Campensis. After a time, he is visited once more by the goddess, who speaks again of mysteries and holy rites which Lucius comes to understand as a command to be initiated into the mysteries of Isis. He does so.

Shortly afterwards, he receives a third vision. Though he is confused, the god appears to him and reassures him that he is much blessed and that he is to become once more initiated that he might supplicate in Rome as well.

The story concludes with the goddess, Isis, appearing to Lucius and declaring that Lucius shall rise to a prominent position in the legal profession and that he shall be appointed to the College of Pastophori ("shrine-bearer", from Ancient Greek: παστοφόρος) that he might serve the mysteries of Osiris and Isis. Lucius is so happy that he goes about freely exposing his bald head.

Inset stories

[edit]Similar to other picaresque novels, The Golden Ass features several shorter stories told by characters encountered by the protagonist. Some act as independent short stories, while others interlock with the original novel's plot developments.

Aristomenes' Tale

[edit]At the beginning of Book One, Lucius encounters two men arguing on the road about the truth of one's story. Lucius is interested, and offers the teller a free lunch for his tale.

Aristomenes goes on business for cheese and he runs into his friend Socrates, who is disheveled and emaciated. Aristomenes clothes Socrates and takes him to the bathhouse. Aristomenes berates Socrates for leaving his family. While they are eating lunch, Socrates tells about his affair with Meroë. Socrates tells Aristomenes that Meroë is an ugly witch who turns her ex-lovers into rather unfortunate animals. Aristomenes doesn't believe Socrates' tale but is nevertheless afraid. Aristomenes barricades the door and they both go to bed. In the middle of the night, Meroë and Panthia break in, cut open Socrates, drain his blood, rip out his heart, and replace it with a sponge. Before leaving, they urinate on Aristomenes. The witches spare Aristomenes because they want him to bury Socrates in the land. Aristomenes fears that he will be blamed for the death of his friend and attempts to hang himself, but is comically stopped when the rope is revealed to be too rotten to support his weight. In the morning, Socrates wakes up and everything seems to be normal. They continue travelling and reach a stream, where Socrates bends to take a drink, which causes the sponge to fall out and him to die. Aristomenes buries Socrates in the ground, and then proceeds on his way.

Thelyphron's Tale

[edit]In Book Two, Thelyphron hesitantly relates a story requested at a dinner party that was previously popular with his friends:

While a student, Thelyphron partakes in many wanderings and eventually runs out of funds. At Larissa, he encounters a large sum being offered to watch over a corpse for the night. Thelyphron is bemused and asks if the dead are accustomed to flee in Larissa. When he asks, a citizen criticises him and tells Thelyphron not to make fun of the task and warns him that shape-shifting witches are quite common in the area, using pieces of human flesh to fuel incantations. Thelyphron takes the job for a thousand drachme and is warned to stay very alert all through the night. The widow is at first hesitant, taking inventory of the body's intact parts. Thelyphron requests a meal and some wine, to which she promptly refuses and leaves him with a lamp for the night. A weasel enters the room and Thelyphron, frightened by its appearance, quickly chases it out, then falls into a deep sleep. At dawn, Thelyphron awakes and rushes over to the body in the room; to his relief, he finds the body intact. The widow enters, and calls for Thelyphron to be paid, satisfied with the intact corpse. Thanking the widow, Thelyphron is suddenly attacked by the crowd and narrowly escapes. He witnesses an elder of the town approach the townspeople desperately and claim that the widow had poisoned her husband to cover up a love affair. The widow protests and supposedly fakes her sadness and a necromancer is called to bring back the deceased for the only truly reliable testimony. The corpse awakes, and affirms the widow's guilt. The corpse then continues to talk and thanks Thelyphron for his trouble; during the night the witches entered as small animals and began to call the corpse and wake him up. By chance, Thelyphron was both the name of the corpse and the guard. Consequently, the witches steal pieces of his ears and nose instead of from the corpse. The witches cleverly replace the missing flesh with wax to delay discovery. Thelyphron touches his nose and ears to find wax fall out of where they once were in the crowd. The crowd laughs at Thelyphron's humiliation.

Tale of Cupid and Psyche

[edit]In Book Four, an elderly woman tells the story to comfort the bandits' captives. The story is continued through Books Five and Six.

Psyche, the most beautiful woman in the world, is envied by her family as well as by Venus. An oracle of Venus demands she be sent to a mountaintop and wed to a murderous beast. Sent by Venus to destroy her, Cupid falls in love and flies her away to his castle. There she is directed to never seek to see the face of her husband, who visits and makes love to her in the dark of night. Eventually, Psyche wishes to see her sisters, who jealously demand she seek to discover the identity of her husband. That night, Psyche discovers her husband is Cupid while he is sleeping, but accidentally burned him with her oil lamp. Infuriated, he flies to heaven and leaves her banished from her castle. In attempted atonement, Psyche seeks the temple of Venus and offers herself as a slave. Venus assigns Psyche four impossible tasks. First, she is commanded to sort through a great hill of mixed grains. In pity, many ants aid her in completing the task. Next, she is commanded to retrieve wool of the dangerous golden sheep. A river god aids Psyche and tells her to gather clumps of wool from thorn bushes nearby. Venus next requests water from a cleft high beyond mortal reach. An eagle gathers the water for Psyche. Next, Psyche is demanded to seek some beauty from Proserpina, Queen of the Underworld. Attempting to kill herself to reach the underworld, Psyche ascends a great tower and prepares to throw herself down. The tower speaks, and teaches Psyche the way of the underworld. Psyche retrieves the beauty in a box, and, hoping to gain the approval of her husband, opens the box to use a little. She is put into a coma. Cupid rescues her, and begs Jupiter that she may become immortal. Psyche is granted Ambrosia, and the two are forever united.

The story is the best-known of those in The Golden Ass and frequently appears in or is referred to directly in later literature.

Tale of the Wife's Tub

[edit]

In the course of a visit to an inn in Book Nine, a smith recounts an anecdote concerning his wife's deceit:

During the day, her husband absent at his labors, the smith's wife is engaged in an adulterous affair. One day, the smith, work finished well ahead of schedule, returns home prematurely—obviously to his wife's great consternation. Panicked, the faithless woman hides her lover in an old tub. After absorbing his spouse's efforts at distraction, which take the form of bitter reproaches that his coming back so early betokens a laziness that can only worsen their poverty, the smith announces that he has sold the tub for six drachmae; to this his wife responds by saying that she has in fact already sold it for seven, and has sent the buyer into the tub to inspect it. Emerging, the lover complains that his supposed purchase is in need of a proper scrubbing if he is to close the deal, so the cuckolded smith gets a candle and flips the tub to clean it from underneath. The canny adulteress then lies atop of the tub and while her lover pleasures her, instructs her hapless husband as to where he should apply his energies. To add insult to injury, the ill-used man eventually has to deliver the tub to the lover's house himself.

Tale of the Jealous Husband

[edit]In Book Nine, a baker's wife of poor reputation is advised by a female 'confidant' to be wary of choosing her lover, suggesting she find one very strong of body and will. She relates the story of one of the wife's previous school friends:

Barbarus, an overbearing husband, is forced to leave on a business trip, and commands his slave, Myrmex, to watch his wife, Aretë, closely to assure she is being faithful during his time away. Barbarus tells Myrmex that any failure will result in his death. Myrmex is so intimidated that he does not let Aretë out of his sight. Aretë's looks charm Philesietaerus who vows to go to any lengths to gain her love. Philesietaerus bribes Myrmex with thirty gold pieces and the promise of his protection for allowing him a night with Aretë. Becoming obsessed with gold, Myrmex delivers the message to Aretë and Philesietaerus pays Myrmex a further ten pieces. While Aretë and Philesietaerus are making love, Barbarus returns but is locked out of the house. Philesietaerus leaves in a hurry, leaving behind his shoes. Barbarus does not notice the strange shoes until the morning, at which point he chains Myrmex's hands and drags him through town, screaming, while looking for the shoes' owner. Philesietaerus spots the two, runs up, and with great confidence shouts at Myrmex, accusing him of stealing his shoes. Barbarus allows Myrmex to live, but beats him for the 'theft'.

Tale of the Fuller's Wife

[edit]In Book Nine the baker's wife attempts to hide her lover from her husband, and entertains to her husband's story of the Fuller:

While coming home with the Baker for supper, the Fuller interrupts his wife's love-making with a lover. She frantically attempts to hide her lover in a drying cage in the ceiling, hidden by hanging clothes soaked in sulphur. The lover begins to sneeze, and at first the Fuller excuses his wife. After a few sneezes, the Fuller gets up and turns over the cage to find the lover waiting. The Fuller is talked out of beating the young man to death by the Baker, who points out that the young man will shortly die from the sulphur fumes if left in the cage. The Fuller agrees and returns the lover to the cage.

The tale is used to contrast the earlier tale told to the Baker's wife of high suspicion and quick judgments of character by her "auntie" with the overly naïve descriptions of nefarious people by her husband.

Tale of the Jealous Wife

[edit]In Book Ten a woman condemned to public humiliation with Lucius tells him her crimes:

A man goes on a journey, leaving his pregnant wife and infant son. He commands his wife that if she bears a daughter, the child is to be killed. The child is indeed a daughter, and in pity, the mother convinces her poor neighbours to raise her. Her daughter grows up ignorant of her origin, and when she reaches a marriageable age, the mother tells her son to deliver her daughter's dowry. The son begins preparation to marry the girl off to a friend, and lets her into his home under the guise of her being an orphan to all but the two of them. His wife is unaware the girl is his sister, and believes he keeps her as a mistress. His wife steals her husband's signet ring and visits their country home accompanied by a group of slaves. She sends a slave with the signet to fetch the girl and bring her to the country home. The girl, aware that the husband is her brother, responds immediately, and on arrival at the country home is flogged by the wife's slaves, and put to death by a torch placed 'between her thighs'. The girl's brother takes the news and falls gravely ill. Aware of suspicions around her, his wife asks a corrupt doctor for instant poison. Accompanied by the doctor, she brings the poison to her husband in bed. Finding him surrounded by friends, she first tricks the doctor into drinking from the cup to prove to her husband the drink is benign, and giving him the remainder. Unable to return home in time to seek an antidote, the doctor dies telling his wife what happened and to at least collect a payment for the poison. The doctor's widow asks for payment but first offers the wife the remainder of her husband's collection of poisons. Finding that her daughter is next of kin to her husband for inheritance, the wife prepares a poison for both the doctor's widow and her daughter. The doctor's widow recognizes early the symptoms of the poison and rushes to the Governor's Home. She tells the Governor the whole of the connected murders and dies. The wife is sentenced to death by wild beasts and to have public intercourse with Lucius the ass.

Overview

[edit]

The text is a precursor to the literary genre of the episodic picaresque novel, in which Francisco de Quevedo, François Rabelais, Giovanni Boccaccio, Miguel de Cervantes, Voltaire, Daniel Defoe and many others have followed. It is an imaginative, irreverent, and amusing work that relates the ludicrous adventures of one Lucius, a virile young man who is obsessed with magic. Finding himself in Thessaly, the "birthplace of magic," Lucius eagerly seeks an opportunity to see magic being used. His overenthusiasm leads to his accidental transformation into an ass. In this guise, Lucius, a member of the Roman country aristocracy, is forced to witness and share the miseries of slaves and destitute freemen who are reduced, like Lucius, to being little more than beasts of burden by their exploitation at the hands of wealthy landowners.

The Golden Ass is the only surviving work of literature from the ancient Greco-Roman world to examine, from a first-hand perspective, the abhorrent condition of the lower classes. Yet despite its serious subject matter, the novel remains imaginative, witty, and often sexually explicit. Numerous amusing stories, many of which seem to be based on actual folk tales, with their ordinary themes of simple-minded husbands, adulterous wives, and clever lovers, as well as the magical transformations that characterize the entire novel, are included within the main narrative. The longest of these inclusions is the tale of Cupid and Psyche, encountered here for the first but not the last time in Western literature.

Style

[edit]Apuleius' style is innovative, mannered, baroque and exuberant, a far cry from the more sedate Latinity familiar from the schoolroom. In the introduction to his translation of The Golden Ass, Jack Lindsay writes:

Let us glance at some of the details of Apuleius' style and it will become clear that English translators have not even tried to preserve and carry over the least tincture of his manner ... Take the description of the baker's wife: saeva scaeva virosa ebriosa pervicax pertinax...(IX.14) The nagging clashing effect of the rhymes gives us half the meaning. I quote two well-known versions: "She was crabbed, cruel, cursed, drunken, obstinate, niggish, phantasmagoric." "She was mischievous, malignant, addicted to men and wine, forward and stubborn." And here is the most recent one (by R. Graves): "She was malicious, cruel, spiteful, lecherous, drunken, selfish, obstinate." Read again the merry and expressive doggerel of Apuleius and it will be seen how little of his vision of life has been transferred into English.

Lindsay's own version is: "She was lewd and crude, a toper and a groper, a nagging hag of a fool of a mule."

Sarah Ruden's recent translation is: "A fiend in a fight but not very bright, hot for a crotch, wine-botched, rather die than let a whim pass by—that was her."[9]

Apuleius' vocabulary is often eccentric and includes some archaic words. S. J. Harrison argues that some archaisms of syntax in the transmitted text may be the result of textual corruption.[10]

Final book

[edit]In the last book, the tone abruptly changes. Driven to desperation by his asinine form, Lucius calls for divine aid, and is answered by the goddess Isis. Eager to be initiated into the mystery cult of Isis, Lucius abstains from forbidden foods, bathes and purifies himself. Then the secrets of the cult's books are explained to him and further secrets revealed, before going through the process of initiation which involves a trial by the elements in a journey to the underworld. Lucius is then asked to seek initiation into the cult of Osiris in Rome, and eventually becomes initiated into the pastophoroi, a group of priests that serves Isis and Osiris.[11]

Adaptations and influence

[edit]The style of autobiographical confession of suffering in The Golden Ass influenced Augustine of Hippo in the tone and style—partly in polemic—of his Confessions.[12] Scholars note that Apuleius came from the Algerian city of M'Daourouch in Souk Ahras Province, where Augustine would later study. Augustine refers to Apuleius and The Golden Ass particularly derisively in The City of God.

In Giovanni Boccaccio's 14th-century work The Decameron, the tenth tale of the fifth day is based on the Tale of the Fuller's Wife, and the second tale of the seventh day is based on the Tale of the Wife's Tub.

The writing of William Shakespeare was influenced by The Golden Ass, e.g., A Midsummer Night's Dream from c. 1595, where the character Bottom's head is transformed to that of an ass.[13]

In 1517, Niccolò Machiavelli wrote his own version of the story, as a terza rima poem. It was uncompleted at the time of his death.[14]

In 1708, Charles Gildon published an adaptation of The Golden Ass, titled The New Metamorphosis. A year later in 1709, he published a re-adaptation, titled The Golden Spy, which is regarded as the first, fully-fledged it-narrative in English.[15]

In 1821, Charles Nodier published "Smarra ou les Demons de la Nuit" influenced by a reading of Apuleius.

In 1883, Carlo Collodi published The Adventures of Pinocchio which includes an episode in which the puppet protagonist is transformed into an ass. Another character who is transformed alongside him is named Lucignolo (Candlewick or Lampwick), a possible allusion to Lucius. The episode is frequently featured in its subsequent adaptations.

In 1885, Walter Pater published Marius the Epicurean, a coming-of-age novel set in Ancient Rome. In Chapter V, he included his own translation of Apuleius' tale of Cupid and Psyche, which profoundly influenced the protagonist's philosophical, aesthetic, and intellectual development.[16]

In 1915, Franz Kafka published the short story The Metamorphosis under a quite similar name, about a young man's unexpected transformation into an "Ungeziefer", a verminous bug.

In 1956, C. S. Lewis published the allegorical novel, Till We Have Faces, retelling the Cupid–Psyche myth from books four through six of The Golden Ass from the point of view of Orual, Psyche's jealous ugly sister. The novel revolves upon the threat and hope of meeting the divine face to face. It has been called Lewis's "most compelling and powerful novel".[17]

In 1985, comic-book artist Georges Pichard adapted the text into a graphic novel titled Les Sorcières de Thessalie.

In April 1999, the Canadian Opera Company produced an operatic version of The Golden Ass by Randolph Peters, the libretto of which was written by celebrated Canadian author Robertson Davies. An operatic production of The Golden Ass also appears as a plot device in Davies's novel A Mixture of Frailties (1958).

In 1999, comic-book artist Milo Manara adapted the text into a fairly abridged graphic novel version named Le metamorfosi o l'asino d'oro.

In the fantasy novel Silverlock by John Myers Myers, the character Lucius Gil Jones is a composite of Lucius, Gil Blas in Gil Blas by Alain-René Lesage, and Tom Jones in The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling by Henry Fielding.

English translations

[edit]- Apuleius; Adlington, William (Trans.) (1566). The Golden Ass. Wordsworth Classics of World Literature, Wordsworth Ed. Ltd.: Ware, GB. ISBN 1-85326-460-1

- Apuleius; Taylor, Thomas (Trans.) (1822). The Metamorphosis, or The Golden Ass, and Philosophical Works, of Apuleius. London: J. Moyes (Suppressed (dirty) passages printed separately.)

- Apuleius; Head, George (Trans.) (1851). The Metamorphosis of Apuleius; A Romance of the Second Century. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. (Bowdlerized)

- Apuleius; Anonymous Translator (Trans.) (1853). The Works of Apuleius. London: Bohn's Library.

- Apuleius; Byrne, Francis D. (Trans.) (1904). The Golden Ass. London: The Imperial Press. (Dirty passages rendered in original Latin.)

- Apuleius; Butler H. E. (Trans.) (1910). The Golden Ass. London: The Clarendon Press. (Dirty passages removed.)

- Apuleius; Graves, Robert (Trans.) (1950). The Golden Ass. Penguin Classics, Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-374-53181-1

- Apuleius; Lindsay, Jack (Trans.) (1962). The Golden Ass. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20036-9

- Apuleius; Hanson, John Arthur (Trans.) (1989). Metamorphoses. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99049-8 (v. 1), ISBN 0-674-99498-1 (v. 2)

- Apuleius; Walsh, P.G. (Trans.) (1994). The Golden Ass. New York: Oxford UP. ISBN 978-0-19-283888-9

- Apuleius; Kenney, E.J. (Trans.) (1998, rev. 2004). The Golden Ass. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-043590-0

- Apuleius; Relihan, Joel C. (Trans.) (2007). The Golden Ass Or, A Book of Changes Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis. ISBN 978-0-87220-887-2

- Apuleius; Ruden, Sarah (Trans.) (2011). The Golden Ass. Yale UP. ISBN 978-0-300-15477-1

- Apuleius; Finkelpearl, Ellen D. (Trans.) (2021) The Golden Ass (edited and abridged by Peter Singer). New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation; London: W.W. Norton and Company, Ltd.

See also

[edit]- Metamorphoses by Ovid, the best-known collection of metamorphosis myths.

- Cupid and Psyche Roman story.

- Silver Age of Latin literature

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ St. Augustine, The City of God 18.18.2

- ^ James Evans (2005). Arts and Humanities Through the Eras. Thomson/Gale. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7876-5699-7.

The "Golden Ass," the only Latin novel to survive in its entirety

- ^ The Golden Ass 1.24

- ^ The Golden Ass 11.27

- ^ Harrison, S.J. (2004) [2000]. Apuleius: A Latin sophist (revised, paperback ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-19-927138-0.

- ^ Perry, Ben Edwin (1920). The Metamorphoses Ascribed to Lucius of Patrae: Its content, nature, and authorship. G.E. Stechert. p. 13.

- ^ Lucius, or The Ass, English translation at attalus.org

- ^ Hanson, John Arthur (1989). Apuleius: Metamorphoses, I (2nd ed.). Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press. pp. xiii, 222. ISBN 0-674-99049-8.

- ^ Apuleius (Sarah Ruden, translator). The Golden Ass. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2011. p. 195

- ^ S. J. Harrison (2006). "Some Textual Problems in Apuleius' Metamorphoses". In W. H. Keulen; et al. (eds.). Lectiones Scrupulosae: Essays on the Text and Interpretation of Apuleius' Metamorphoses in Honour of Maaike Zimmerman. Ancient Narrative Supplementum. Groningen: Barkhuis. pp. 59–67. ISBN 90-77922-16-4.

- ^ Iles Johnson, Sarah, Mysteries, in Ancient Religions pp. 104–05, The Belknap Press of Harvard University (2007), ISBN 978-0-674-02548-6

- ^ Walsh, P.G. (1994). Introduction. The Golden Ass. Oxford: Oxford UP. ISBN 9780198149323 p. xi

- ^ Carver, R. (2007-12-06). Shakespeare's Bottom and Apuleius' Ass. In The Protean Ass: The Metamorphoses of Apuleius from Antiquity to the Renaissance. : Oxford University Press. Retrieved 27 Jul. 2022, from https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199217861.001.0001/acprof-9780199217861-chapter-13.

- ^ Patapan, Haig (2006). Machiavelli in Love: The Modern Politics of Love and Fear. Oxford: Lexington Press. ISBN 978-0-7391-1250-2 p. 61.

- ^ Wu, Jingyue (2017), ‘ “Nobilitas sola est atq; unica Virtus”: Spying and the Politics of Virtue in The Golden Spy; or, A Political Journal of the British Nights Entertainments (1709)’, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 40:2 (2017), pp. 237–53 doi:10.1111/1754-0208.12412

- ^ Pater, Walter. "Marius the Epicurean — Volume 1". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2025-02-22.

- ^ Filmer, Kath (1993). The Fiction of C. S. Lewis: Mask and Mirror. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press. p. 120. ISBN 9781349225378. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

References and further reading

[edit]- Benson, G. (2019). Apuleius’ Invisible Ass: Encounters with the Unseen in the Metamorphoses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carver, Robert H. F. (2007). The Protean Ass: The 'Metamorphoses' of Apuleius from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921786-1

- De Smet, Richard. (1987). "The Erotic Adventure of Lucius and Photis in Apuleius' Metamorphoses." Latomus 46.3: 613–23. Société d'Études Latines de Bruxelles.

- Fletcher, K. F. B. (2023). The Ass of the Gods. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004537163.

- Gaisser, J. Haig. (2008). The Fortunes of Apuleius and the Golden Ass: A Study in Transmission and Reception. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gorman, S. (2008). "When the Text Becomes the Teller: Apuleius and the Metamorphoses." Oral Tradition 23(1), Center for Studies in Oral Tradition

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn (1975). Apuleius of Madauros: The Isis-Book (Metamorphoses, Book XI). E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-04270-9

- Harrison, S. (2000). Apuleius. A Latin Sophist. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Harrison, S. (ed.) (2015). Characterisation in Apuleius' Metamorphoses: Nine Studies. Pierides, 5. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Harrison, S. J. (2013). Framing the Ass: Literary Texture in Apuleius' Metamorphoses. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hooper, R. (1985). Structural Unity in the Golden Ass. Latomus, 44(2), 398–401.

- Kenney, E. (2003). "In the Mill with Slaves: Lucius Looks Back in Gratitude." Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974–) 133.1: 159–92.

- Keulen, W. H. (2011). Aspects of Apuleius' Golden Ass : The Isis Book: A Collection of Original Papers. Leiden: Brill.

- Kirichenko, A. (2008). "Asinus Philosophans: Platonic Philosophy and the Prologue to Apuleius' "Golden Ass."" Mnemosyne, 61(1), fourth series, 89–107.

- Lee, Benjamin Todd, Ellen D Finkelpearl, and Luca Graverini. (2014). Apuleius and Africa. New York;London: Routledge.

- May, R. (2006). Apuleius and Drama: The Ass on Stage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oswald, Peter (2002). The Golden Ass or the Curious Man. Comedy in Three Parts after the Novel by Lucius Apuleius. London: Oberon Books. ISBN 1-84002-285-X

- O'Sullivan, Timothy M. (2017). "Human and Asinine Postures in Apuleius' Golden Ass." The Classical Journal, 112.2: 196–216.

- Paschalis, M., & Frangoulidis, S. A. (2002). Space in the Ancient Novel. Groningen: Barkhuis Publishing.

- Perry, B. E. (2016). "An Interpretation of Apuleius' Metamorphoses." Illinois Classical Studies 41.2: 405–21

- Schlam, C. (1968). The Curiosity of the Golden Ass. The Classical Journal, 64.3: 120–25.

- Schoeder, F. M. (2008). "The Final Metamorphosis: Narrative Voice in the Prologue of Apuleius' Golden Ass." In S. Stern-Gillet, and K. Corrigan (eds.), Reading Ancient Texts : Aristotle and Neoplatonism – Essays in Honour of Denis O'Brien, 115–35. Boston: Brill.

- Stevenson, S. (1934). "A Comparison of Ovid and Apuleius as Story-Tellers." The Classical Journal 29.8: 582–90.

- Tatum, J. (1969). "The Tales in Apuleius' Metamorphoses." Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 100: 487–527.

- Tilg, Stefan (2014). Apuleius' Metamorphoses: A Study in Roman Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870683-0

- Wright, C. S, Holloway, J. Bolton, & Schoeck, R. J. (2000). Tales within Tales: Apuleius Through Time. New York: AMS Press.

External links

[edit]- Forum Romanum: Metamorphoses (Latin text only.)

- Metamorphoseon libri XI, a Teubner critical edition, published in 1897

- William Adlington's English translation made in 1566:

- The Golden Ass at Standard Ebooks

- Project Gutenberg: The Golden Asse (Plain text.)

- The Most Pleasant and Delectable Tale of the Marriage of Cupid and Psyche (Excerpt illustrated by Dorothy Mullock, 1914.)

Metamorphosis or The Golden Ass public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Metamorphosis or The Golden Ass public domain audiobook at LibriVox- The Spectacles of Apuleius: a digital humanities project on the Metamorphoses of Apuleius

- Metamorphoses at Perseus Digital Library

Commentaries

- The Golden Ass by Apuleius, essay by Ted Gioia (Conceptual Fiction)

- The Golden Ass by B. Slade

- Book One and Apuleius' Metamorphoses," in J. S. Ruebel, Apuleius: Metamorphoses Book I. (PDF.)