Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

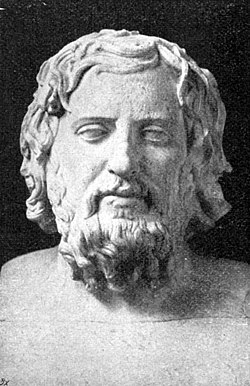

Niccolò Machiavelli

View on Wikipedia

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli[a] (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine[4][5] diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise The Prince (Il Principe), written around 1513 but not published until 1532, five years after his death.[6] He has often been called the father of modern political philosophy and political science.[7]

Key Information

For many years he served as a senior official in the Florentine Republic with responsibilities in diplomatic and military affairs. He wrote comedies, carnival songs, and poetry. His personal correspondence is also important to historians and scholars of Italian correspondence.[8] He worked as secretary to the second chancery of the Republic of Florence from 1498 to 1512, when the Medici were out of power.

After his death Machiavelli's name came to evoke unscrupulous acts of the sort he advised most famously in his work, The Prince.[9] He concerned himself with the ways a ruler could succeed in politics, and believed those who flourished engaged in deception, treachery, and violence.[10] He advised rulers to engage in evil when political necessity requires it, at one point stating that successful founders and reformers of governments should be excused for killing other leaders who would oppose them.[11][12][13] Machiavelli's Prince has been surrounded by controversy since it was published. Some consider it to be a straightforward description of political reality. Many view The Prince as a manual, teaching would-be tyrants how they should seize and maintain power.[14] Even into recent times, scholars such as Leo Strauss have restated the traditional opinion that Machiavelli was a "teacher of evil".[15]

Even though Machiavelli has become most famous for his work on principalities, scholars also give attention to the exhortations in his other works of political philosophy. The Discourses on Livy (composed c. 1517) has been said to have paved the way for modern republicanism.[16] His works were a major influence on Enlightenment authors who revived interest in classical republicanism, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and James Harrington.[17] Machiavelli's philosophical contributions have influenced generations of academics and politicians, with many of them debating the nature of his ideas.[18]

Life

[edit]

Niccolò Machiavelli was born in Florence, Italy, the third child and first son of attorney Bernardo di Niccolò Machiavelli and his wife, Bartolomea di Stefano Nelli, on 3 May 1469.[19] The Machiavelli family is believed to be descended from the old marquesses of Tuscany and to have produced thirteen Florentine Gonfalonieres of Justice,[20] one of the offices of a group of nine citizens selected by drawing lots every two months and who formed the government, or Signoria; he was never, though, a full citizen of Florence because of the nature of Florentine citizenship in that time even under the republican regime. Not much is known about Machiavelli's early life, thus one of the main sources that historians rely on regarding his experiences exists in his father's diary, found in the 20th century.[21] His family was a huge influence on his life, and it is said that it was his heritage which instilled Machiavelli with his preference for a republican form of government. There isn't much known about Machiavelli's mother as few facts have been found about her life by historians.[22]

Machiavelli was born in a tumultuous era. The Italian city-states, and the families and individuals who ran them could rise and fall suddenly, as popes and the kings of France, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire waged acquisitive wars for regional influence and control. Political-military alliances continually changed, featuring condottieri (mercenary leaders), who changed sides without warning, and the rise and fall of many short-lived governments.[23]

Machiavelli was taught grammar, rhetoric, and Latin by his teacher, Paolo da Ronciglione.[24] It is unknown whether Machiavelli knew Greek; Florence was at the time one of the centres of Greek scholarship in Europe.[25] In 1494 Florence restored the republic, expelling the Medici family that had ruled Florence for some sixty years.[26]

Diplomatic career

[edit]Shortly after the execution of Savonarola, Machiavelli was appointed to an office of the second chancery, a medieval writing office that put Machiavelli in charge of the production of official Florentine government documents.[27] Shortly thereafter, he was also made the secretary of the Dieci di Libertà e Pace, the Florentine council responsible for diplomacy and warfare.[28][29] His appointment remains a mystery to scholars as he was a very young man, 29 at the time, with no experience in law or public office.[30]

Machiavelli married Marietta Corsini in 1501. They had seven children, five sons and two daughters: Primerana, Bernardo, Lodovico, Guido, Piero, Baccina and Totto.[31][32]

Machiavelli's position as a secretary enabled him to witness firsthand the state-building methods of the Pope Alexander VI, and his son, Cesare Borgia. Machiavelli often wrote highly about Cesare, stating in one letter that "this lord is splendid and magnificent", and that his pursuit of glory he "knows neither danger or fatigue".[33] Machiavelli personally witnessed the brutal retribution Cesare Borgia inflicted on his rebellious commanders, Oliverotto Euffreducci and Vitellozzo Vitelli in Sinigaglia on December 31, 1502, an event he famously chronicled in a political work, A description of the methods adopted by the Duke Valentino when murdering Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, the Signor Pagolo, and the Duke di Gravina Orsini. In many of his early writings, Machiavelli emphasized the danger of offending a ruler and then expecting to trust him afterward. In 1503, Machiavelli was dispatched to Rome to observe the papal conclave that ultimately selected Julius II, who was a bitter rival of the Borgia family, as pope, despite Cesare’s support for his election. As Cesare’s power waned, Machiavelli documented his downfall in his poem First Decennale.[34][35]

Machiavelli also was present during Pandolfo Petrucci's consolidation of his rule in Siena, later noting in his works that he "governed his state more with those who were suspected of him than with others".[36]

In the first decade of the sixteenth century, he carried out several diplomatic missions, most notably to the papacy in Rome. Florence sent him to Pistoia to pacify the leaders of two opposing factions which had broken into riots in 1501 and 1502; when this failed, the leaders were banished from the city, a strategy which Machiavelli had favoured from the outset.[37] Machiavelli’s official duties within the Florentine Republic, including his involvement in the disturbances of Pistoia and the rebellion of Arezzo, were not of major political consequence but served as critical experiences that shaped his intellectual development.[38] Though his influence was subtle, often exerted through anonymous chancery work, biographers suggest he advocated for firm punishment of rebellious cities, a stance consistent with his known political attitudes, even if not fully implemented.[39] These events, and the evident structural weaknesses of Florence’s government compared to figures like Borgia, offered Machiavelli valuable insights. While his official report De rebus pistoriensibus was routine and unremarkable, his later discourse Del modo di trattare i sudditi della Valdichiana ribellati marked a turning point as it was more reflective and analytical, blending historical knowledge with political thought, and is considered his first mature, literary political work not driven by immediate bureaucratic necessity.[40]

At the start of the 16th century, Machiavelli conceived of a militia for Florence, and he then began recruiting and creating it.[41] He distrusted mercenaries (a distrust that he explained in his official reports and then later in his theoretical works for their unpatriotic and uninvested nature in the war that makes their allegiance fickle and often unreliable when most needed),[42] and instead staffed his army with citizens, a policy that yielded some positive results. By February 1506 he was able to have four hundred farmers marching on parade, suited (including iron breastplates), and armed with lances and small firearms.[41] Under his command, Florentine citizen-soldiers conquered Pisa in 1509.[43]

Exile and later years

[edit]Machiavelli's success was short-lived. In August 1512, the Medici, backed by Pope Julius II, used Spanish troops to defeat the Florentines at Prato.[44] In the wake of the siege, Piero Soderini resigned as Florentine head of state and fled into exile. The experience would, like Machiavelli's time in foreign courts and with the Borgia, heavily influence his political writings. The Florentine city-state and the republic were dissolved. Machiavelli was ordered to remain in Florence for a year, and to pay a surety of one thousand florins. He was falsely implicated in a conspiracy to remove the Medici family from power merely because his name was on a list of possible sympathizers.[45][46] Despite being subjected to torture[47] ("with the rope", in which the prisoner is hanged from his bound wrists from the back, forcing the arms to bear the body's weight and dislocating the shoulders), he denied involvement and was released after three weeks.[48]

Machiavelli then retired to his farm estate at Sant'Andrea in Percussina, near San Casciano in Val di Pesa, where he devoted himself to studying and writing political treatises. During this period, he represented the Florentine Republic on diplomatic visits to France, Germany, and elsewhere in Italy.[47] Despairing of the opportunity to remain directly involved in political matters, after a time he began to participate in intellectual groups in Florence and wrote several plays that (unlike his works on political theory) were both popular and widely known in his lifetime. Politics remained his main passion, and to satisfy this interest, he maintained a well-known correspondence with more politically connected friends, attempting to become involved once again in political life.[49] Machiavelli had a lengthy correspondence with his close friend, Francesco Vettori.[50] In one of his letters which he details his life after his exile, he described his latest project as one of his "whimsies" that would later be called Il Principe (The Prince), and that he is planning on filling the work "with everything he knows".[51] As the letter to Vettori continues, he described his current situation:

When evening comes, I go back home, and go to my study. On the threshold, I take off my work clothes, covered in mud and filth, and I put on the clothes an ambassador would wear. Decently dressed, I enter the ancient courts of rulers who have long since died. There, I am warmly welcomed, and I feed on the only food I find nourishing and was born to savour. I am not ashamed to talk to them and ask them to explain their actions and they, out of kindness, answer me. Four hours go by without my feeling any anxiety. I forget every worry. I am no longer afraid of poverty or frightened of death. I live entirely through them.[52]

Though scholars often debate on the time of the composition of the Discourses on Livy, it is often said that he was composing the work in the years between 1515 and 1517.[53]

From 1516 Machiavelli had freqented the Orti Oricellari gardens, a place where it was common for humanists and philosophers to discuss anti-tyrannical themes, and it was in these gardens where Machiavelli gained a friendship with Bernardo Rucellai and Zanobi Buondelmonti, men whom Machiavelli would dedicate his Discoursi to.[54]

In 1520, Machiavelli won the favor of the Medici family, and Giulio Cardinal de Medici commissioned him to write a work of history of the city of Florence. Machiavelli saw this as an opportunity to get back into his political career, thus he began working on what would later be known as The Florentine Histories.[55][56] During this period, Machiavelli also wrote the Dell'arte della guerra, which was the only work published during his lifetime.[57]

In his exile, he also wrote plays, including Clizia, The Mandrake (La Mandragola), and The Golden Ass.[58]

After the 1527 Sack of Rome, the Medici were thrown out of Florence once more, and citizens set up a republican form of government. There were discussions to give Machiavelli a post in this new government, which were rejected due to the favors he was given to by the Medici.[59]

Death and burial

[edit]Machiavelli died on 21 June 1527 from a stomach disease[60]that he had been suffering from since 1525.[61] He died at the age of 58 after receiving his last rites.[62][63] He was buried at the Church of Santa Croce in Florence. In 1789 George Nassau Clavering, and Pietro Leopoldo, Grand Duke of Tuscany, initiated the construction of a monument on Machiavelli's tomb. It was sculpted by Innocenzo Spinazzi, with an epitaph by Doctor Ferroni inscribed on it.[64][b]

Major works

[edit]The Prince

[edit]

Machiavelli's best-known book Il Principe contains several maxims concerning politics. Instead of the more traditional target audience of a hereditary prince, it concentrates on the possibility of a "new prince". To retain royal authority, the hereditary prince does not have to do much to keep his position, as Machiavelli states that only an "excessive force" will deprive him of his rule.[65] By contrast, a new prince has the more difficult task in ruling: He must first stabilize his newfound power in order to build an enduring political structure. Machiavelli views that the virtues often recommended to princes actually hinder their ability to rule, thus a prince must learn to be able to act opposite said virtues in order to maintain his regime.[66] A ruler must be concerned not only with reputation, but also must be positively willing to act unscrupulously at the right times. Machiavelli believed that, for a ruler, it was better to be widely feared than to be greatly loved; a loved ruler retains authority by obligation, while a feared leader rules by fear of punishment.[67] As a political theorist, Machiavelli emphasized the "necessity" for the methodical exercise of brute force or deceit, including extermination of entire noble families, to head off any chance of a challenge to the prince's authority.[68]

Scholars often note that Machiavelli glorifies instrumentality in state building, an approach embodied by the saying, often erroneously attributed to Machiavelli, "The ends justify the means".[69][70] Fraud and deceit are held by Machiavelli as necessary for a prince to use.[71] Violence may be necessary for the successful stabilization of power and introduction of new political institutions. Force may be used to eliminate political rivals, destroy resistant populations, and purge the community of other men strong enough of a character to rule, who will inevitably attempt to replace the ruler.[72] In one passage, Machiavelli subverts the advice given by Cicero to avoid duplicity and violence, by saying that the prince should "be the fox to avoid the snares, and a lion to overwhelm the wolves". It would become one of Machiavelli's most famous maxims.[73] Machiavelli's view that acquiring a state and maintaining it requires evil means has been noted as the chief theme of the treatise.[74] Machiavelli has become infamous for such political advice, ensuring that he would be remembered in history through the adjective "Machiavellian".[75]

Due to the treatise's controversial analysis on politics, in 1559, the Catholic Church banned The Prince, putting it on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.[76][77] Humanists, including Erasmus (c. 1466 – 1536), also viewed the book negatively. As a treatise, its primary intellectual contribution to the history of political thought is the fundamental break between political realism and political idealism, due to it being a manual on acquiring and keeping political power.[78] In contrast with—and in opposition to—Plato and Aristotle, Machiavelli insisted that "imaginary republics and principalities" i.e. the realization of the best political regime is not possible, and as such a prince must seek the "effectual truth" (verita effetuale).[79][80]

Concerning the differences and similarities in Machiavelli's advice to ruthless and tyrannical princes in The Prince and his more republican exhortations in Discourses on Livy, a few commentators assert that The Prince, although written as advice for a monarchical prince, contains arguments for the superiority of republican regimes, similar to those found in the Discourses. In the 18th century, the work was even called a satire, for example by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778).[81][82] This however is an interpretation that is often refuted by scholars.[83]

Scholars such as Leo Strauss (1899–1973) and Harvey Mansfield (b. 1932) have stated that sections of The Prince and his other works have deliberately esoteric statements throughout them.[84] However, Mansfield states that this is the result of Machiavelli's seeing grave and serious things as humorous because they are "manipulable by men", and sees them as grave because they "answer human necessities".[85]

The Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) argued that Machiavelli's audience was the common people, as opposed to the ruling class, who were already made aware of the methods described through their education.[86]

Discourses on Livy

[edit]The Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livius, written around 1517, and published in 1531, often referred to simply as the Discourses or Discorsi, is nominally a discussion regarding the classical history of early Ancient Rome, although it strays far from this subject matter and also uses contemporary political examples to illustrate points. Machiavelli presents it as a series of lessons on how a republic should be started and structured. It is a larger work than The Prince, and while it more openly explains the advantages of republics, it also contains many similar themes from his other works.[87] For example, Machiavelli has noted that to save a republic from corruption, it is necessary to return it to a "kingly state" using violent means.[88] He excuses Romulus for murdering his brother Remus and co-ruler Titus Tatius to gain absolute power for himself in that he established a "civil way of life", or a kingdom with laws suitable for a republic.[89][90] Commentators disagree about how much the two works agree with each other, as Machiavelli frequently refers to leaders of republics as "princes".[91] Machiavelli even sometimes acts as an advisor to tyrants.[92][93] Other scholars have pointed out the aggrandizing and imperialistic features of Machiavelli's republic.[94] It became one of the central texts of modern republicanism, and has been argued by Pocock to be a more comprehensive work than The Prince.[95]

Florentine Histories

[edit]Art of War

[edit]The Art of War is divided into a preface (proemio) and seven books (chapters), which take the form of a series of dialogues that take place in the Orti Oricellari, the gardens built in a classical style by Bernardo Rucellai in the 1490s for Florentine aristocrats and humanists to engage in discussion, between Cosimo Rucellai and "Lord Fabrizio Colonna" (many feel Colonna is a veiled disguise for Machiavelli himself, but this view has been challenged by scholars such as Mansfield)[101], with other patrizi and captains of the recent Florentine republic: Zanobi Buondelmonti, Battista della Palla and Luigi Alamanni. The work is dedicated to Lorenzo di Filippo Strozzi, patrizio fiorentino in a preface which ostentatiously pronounces Machiavelli's authorship. After repeated uses of the first-person singular to introduce the dialogue, Machiavelli retreats from the work, serving as neither narrator nor interlocutor.[101] Fabrizio is enamored with the Roman Legions of the early to mid Roman Republic and strongly advocates adapting them to the contemporary situation of Renaissance Florence.

Fabrizio dominates the discussions with his knowledge, wisdom and insights. The other characters, for the most part, simply yield to his superior knowledge and merely bring up topics, ask him questions or for clarification. These dialogues, then, often become monologues with Fabrizio detailing how an army should be raised, trained, organized, deployed and employed.Originality

[edit]

Major commentary on Machiavelli's work has focused on two issues: how unified and philosophical his work is and how innovative or traditional it is.[102]

Coherence

[edit]There is some disagreement concerning how best to describe the unifying themes, if there are any, that can be found in Machiavelli's works, especially in the two major political works, The Prince and Discourses. Some commentators have described him as inconsistent, and perhaps as not even putting a high priority on consistency.[102][103] Others such as Hans Baron have argued that his ideas must have changed dramatically over time. Some have argued that his conclusions are best understood as a product of his times, experiences and education. Others, such as Leo Strauss and Harvey Mansfield, have argued strongly that there is a strong and deliberate consistency and distinctness, even arguing that this extends to all of Machiavelli's works including his comedies and letters.[102][104]

Influences

[edit]Commentators such as Leo Strauss have gone so far as to name Machiavelli as the deliberate originator of modernity itself. Others have argued that Machiavelli is only a particularly interesting example of trends which were happening around him. In any case, Machiavelli presented himself at various times as someone reminding Italians of the old virtues of the Romans and Greeks, and other times as someone promoting a completely new approach to politics.[102] Machiavelli emphasizes the originality of his endeavor in several instances. Many scholars note that Machiavelli seems particularly original and that he frequently seems to act without any regard for his predecessors.[105][106]

That Machiavelli had a wide range of influences is in itself not controversial. Their relative importance is however a subject of ongoing discussion. It is possible to summarize some of the main influences emphasized by different commentators.

The Mirror of Princes genre

Gilbert (1938) summarized the similarities between The Prince and the genre it imitates, the so-called "Mirror of Princes" style. This was a classically influenced genre, with models at least as far back as Xenophon and Isocrates. While Gilbert emphasized the similarities, however, he agreed with all other commentators that Machiavelli was particularly novel in the way he used this genre, even when compared to his contemporaries such as Baldassare Castiglione and Erasmus.[107] One of the major innovations Gilbert noted was that Machiavelli focused on the "deliberate purpose of dealing with a new ruler who will need to establish himself in defiance of custom".[108] Normally, these types of works were addressed only to hereditary princes. (Xenophon is also an exception in this regard.)

Classical republicanism

Commentators such as Quentin Skinner and J.G.A. Pocock, in the so-called "Cambridge School" of interpretation, have asserted that some of the republican themes in Machiavelli's political works, particularly the Discourses on Livy, can be found in medieval Italian literature which was influenced by classical authors such as Sallust.[109][110]

Classical political philosophy: Xenophon, Plato and Aristotle

Political thinkers usually engage to some extent with their forerunners, even (or perhaps particularly) those who aim to fundamentally disagree with prior thoughts.[111] Therefore, even with a figure as seemingly innovative as Machiavelli, scholars have looked deeper into his works to consider possible historical and philosophical influences. Although Machiavelli examined ancient philosophers, he does not frequently reference them as authorities. He mentions neither Plato nor Aristotle in The Prince, and he mentions Aristotle only once in The Discourses.[112] He usually does not speak of philosophers as such, but mentions "writers" and "authors".[113] One of the writers Machiavelli mentions the most is Xenophon.[114] In his time, the most commonly cited discussion of classical virtues was Book One of Cicero’s De Officiis. Yet, Cicero is never directly mentioned in The Prince, and is mentioned only three times in the Discourses.[115]

The major difference between Machiavelli and the Socratics, according to Strauss, is Machiavelli's materialism, and therefore his rejection of both a teleological view of nature and of the view that philosophy is higher than politics. With their teleological understanding of things, Socratics argued that by nature, everything that acts, acts towards some end, as if nature desired them, but Machiavelli claimed that such things happen by blind chance or human action.[116]

Classical materialism

Strauss argued that Machiavelli may have seen himself as influenced by some ideas from classical materialists such as Democritus, Epicurus and Lucretius. Strauss however sees this also as a sign of major innovation in Machiavelli, because classical materialists did not share the Socratic regard for political life, while Machiavelli clearly did.[116]

Thucydides

Some scholars note the similarity between Machiavelli and the Greek historian Thucydides, since both emphasized power politics.[117][118] Strauss argued that Machiavelli may indeed have been influenced by pre-Socratic philosophers, but he felt it was a new combination:

...contemporary readers are reminded by Machiavelli's teaching of Thucydides; they find in both authors the same "realism", i.e., the same denial of the power of the gods or of justice and the same sensitivity to harsh necessity and elusive chance. Yet Thucydides never calls in question the intrinsic superiority of nobility to baseness, a superiority that shines forth particularly when the noble is destroyed by the base. Therefore Thucydides' History arouses in the reader a sadness which is never aroused by Machiavelli's books. In Machiavelli we find comedies, parodies, and satires but nothing reminding of tragedy. One half of humanity remains outside of his thought. There is no tragedy in Machiavelli because he has no sense of the sacredness of "the common". – Strauss (1958, p. 292)

Beliefs

[edit]Amongst commentators, there are a few consistently made proposals concerning what was most new in Machiavelli's work.

Empiricism and realism versus idealism

[edit]Machiavelli is sometimes seen as the prototype of a modern empirical scientist, building generalizations from experience and historical facts, and emphasizing the uselessness of theorizing with the imagination.[102]

He was not only a theorist of monarchical rule in The Prince, but, paradoxically, an ardent republican. He was a religious radical, rejecting not only the contemporary Catholic church but Christianity as such; he may even have been a clandestine atheist.

— Robert Black, 2022[119]

Machiavelli often switches between his professed novelty of his ideas and his evident reliance on ancient history. In the preface to the first book of The Discourses, he presents himself as both a discoverer of "new modes and orders" and as a restorer of the ancient understanding of politics.[120] While he viewed the classical approach to government to be self-limiting and harmful in many cases, he nonetheless attributes this to a false understanding of political history.[121] Moreover, he studied the way people lived and aimed to inform leaders how they should rule and even how they themselves should live. Machiavelli denies the classical opinion that living virtuously always leads to happiness. For example, Machiavelli viewed misery as "one of the vices that enables a prince to rule."[122] Machiavelli stated that "it would be best to be both loved and feared. But since the two rarely come together, anyone compelled to choose will find greater security in being feared than in being loved."[123] In much of Machiavelli's work, he often states that the ruler must adopt unsavoury policies for the sake of the continuance of his regime. Because cruelty and fraud play such important roles in his politics, it is not unusual for certain issues (such as murder and betrayal) to be commonplace within his works.[124] Machiavelli also places his focus specifically on the beginnings and foundations of political societies, where a lawful government has to be established by extralegal methods.[125][126]

A related and more controversial proposal often made is that he described how to do things in politics in a way which seemed neutral concerning who used the advice – tyrants or good rulers.[102] That Machiavelli strove for realism is not doubted, but for four centuries scholars have debated how best to describe his morality. The Prince made the word Machiavellian a byword for deceit, despotism, and political manipulation. Leo Strauss declared himself as sympathetic toward the traditional view that Machiavelli was self-consciously a "teacher of evil", since he recommends princes to avoid the values of justice, mercy, temperance, and wisdom, in preference to the use of cruelty, violence, terror, and deception.[127] Strauss takes up this opinion because he asserted that failure to accept the traditional opinion misses the "intrepidity of his thought" and "the graceful subtlety of his speech".[128] Italian anti-fascist philosopher Benedetto Croce (1925) concludes Machiavelli is simply a "realist" or "pragmatist" who accurately states that moral values, in reality, do not greatly affect the decisions that political leaders make.[129] German philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1946) held that Machiavelli merely adopts the stance of a political scientist – a Galileo of politics – in distinguishing between the actuality of politics instead of providing value judgements on political morality.[130] With a focus on Machiavelli's ideas on the foundations of cities and societies, Louis Althusser stated that Machiavelli was a "theorist of beginnings".[131]

Fortune

[edit]Machiavelli is generally seen as being critical of Christianity as it existed in his time, specifically its effect upon politics and humanity in general.[132] In his opinion, the Christianity that the Church had come to accept allowed practical decisions to be guided too much by imaginary ideals and encouraged people to lazily leave events up to providence or, as he would put it, chance, luck or fortune. Machiavelli took a radically different view, and opined that the pagan religion, given it's faults, was preferable to Christianity as it championed martial warfare.[133] Machiavelli's own concept of virtue, which he calls "virtù", is original and is usually seen by scholars as different from the traditional viewpoints of other political philosophers.[134] Virtù can consist of any quality at the moment that helps a ruler maintain his state, even being ready to engage in necessary evil when it is advantageous.[135][136][137] Harvey Mansfield (1995, p. 74) wrote of Machiavelli's followers that: "In attempting other, more regular and scientific modes of overcoming fortune, Machiavelli's successors formalized and emasculated his notion of virtue." Mansfield describes Machiavelli's usage of virtù as a "compromise with evil".[138] Mansfield however argues that Machiavelli's own aims have not been shared by those he influenced. Machiavelli argued against seeing mere peace and economic growth as worthy aims on their own if they would lead to what Mansfield calls the "taming of the prince".[139]

Najemy has argued that this same approach can be found in Machiavelli's approach to love and desire, as seen in his comedies and correspondence. Najemy shows how Machiavelli's friend Vettori argued against Machiavelli and cited a more traditional understanding of fortune.[140]

Cary Nederman says of Machiavelli's use of fortuna that: "Machiavelli’s remarks point toward several salient conclusions about Fortuna and her place in his intellectual universe. Throughout his corpus, Fortuna is depicted as a primal source of violence (especially as directed against humanity) and as antithetical to reason. Thus, Machiavelli realizes that only preparation to pose an extreme response to the vicissitudes of Fortuna will ensure victory against her. This is what virtù provides: the ability to respond to fortune at any time and in any way that is necessary."[141] On Machiavelli's use of virtu, Quentin Skinner noted that "properly understood, the princely virtues are among the qualities that go to make up the virtù of a truly virtuoso prince, thereby helping him to fulfil his primary duty of maintaining the state in a condition of security and peace." [142]

Strauss concludes his 1958 book Thoughts on Machiavelli by proposing that "The difficulty implied in the admission that inventions pertaining to the art of war must be encouraged is the only one which supplies a basis for Machiavelli’s criticism of classical political philosophy." and that this shows that classical-minded men "had to admit in other words that in an important respect the good city has to take its bearings by the practice of bad cities or that the bad impose their law on the good".Strauss (1958, pp. 298–299)

Religion

[edit]Machiavelli shows repeatedly that he saw religion as man-made, and that the value of religion lies in its contribution to social order and the rules of morality must be dispensed with if security requires it.[143][144] In The Prince, the Discourses and in the Life of Castruccio Castracani he describes "prophets", as he calls them, like Moses, Romulus, Cyrus the Great and Theseus as the greatest of new princes, the glorious and brutal founders of the most novel innovations in politics, and men whom Machiavelli assures us have always used armed force, being willing to kill those who did not ultimately agree with their vision.[145][146] He estimated that these sects last from 1,666 to 3,000 years each time, which, as pointed out by Leo Strauss, would mean that Christianity became due to start finishing about 150 years after Machiavelli.[147] Machiavelli's concern with Christianity as a religion was that it made the Italians of his day "weak and effeminate", delivering politics into the hands of cruel and wicked men without a fight, as well as celebrated humility and otherworldly things, instead of being focused on the tangible world.[148] While Machiavelli's own religious allegiance has been debated, it is assumed that he had a low regard of contemporary Christianity.[149] Some scholars, like Sebastian De Grazia and Maurizio Viroli, view that Machiavelli viewed religion more intimately than previously thought.[150][151] In contrast, Nathan Tarcov has noted that Machiavelli's praise of religion, in actuality, provides cover for his anti-clericalism and antipathy towards Christianity proper.[152] Vickie Sullivan similarly argues that, for Machiavelli, Chrisitianity made the practice of free government impossible.[153]

While fear of God can be replaced by fear of the prince, if there is a strong enough prince, Machiavelli felt that having a religion is in any case especially essential to keeping a republic in order.[154] For Machiavelli, a truly great prince can never be conventionally religious himself, but he should make his people religious if he can. According to Strauss (1958, pp. 226–227) he was not the first person to explain religion in this way, but his description of religion was novel because of the way he integrated this into his general account of princes.

Machiavelli's judgment that governments need religion for practical political reasons was widespread among modern proponents of republics until approximately the time of the French Revolution. This, therefore, represents a point of disagreement between Machiavelli and late modernity.[155]

Terminology

[edit]Stato

Another term of Machiavelli's that scholars debate over is his use of the word stato (literally translated as "state"). Whenever he uses the word, it usually refers to a regime's political command to which a leader takes a hold of, and rules over himself.[156][157] Generally he believes that in all states, there exists two humors, that of the great, who wish to rule and oppress others, and that of the people, who do not seek to oppress.[158] Glory plays a central role in Machiavelli’s political thought, drawing heavily on the Roman ideal of gloria, which emphasized public recognition for one's achievements, especially in warfare or public service.[159][160]

Republicanism

The majority of scholars have taken into account Machiavelli's admiration of, and recommendations to republics, and his contribution to republican theory. Machiavelli gives lengthy advice for republics in how they can best protect their liberties, and how they can avoid those who would ultimately usurp legitimate authority.[161] Even in this, commentators have no consensus as to the exact nature of his republicanism. For example, the "Cambridge School" of interpretation holds Machiavelli to be a civic humanist and classical republican who viewed that the highest quality of republican virtue is self-sacrifice for the common good.[162] However this opinion has been contested by scholars who believe that Machiavelli has a radically modern view of republics, accepting and unleashing the self interest of those who rule.[163][164] Some scholars have even asserted that the goal of his ideal republic does not differ greatly from his principality, as both rely on rather ruthless measures for conquest and empire.[165][166]

Influence

[edit]

To quote Robert Bireley:[167]

...there were in circulation approximately fifteen editions of the Prince and nineteen of the Discourses and French translations of each before they were placed on the Index of Paul IV in 1559, a measure which nearly stopped publication in Catholic areas except in France. Three principal writers took the field against Machiavelli between the publication of his works and their condemnation in 1559 and again by the Tridentine Index in 1564. These were the English cardinal Reginald Pole and the Portuguese bishop Jeronymo Osorio, both of whom lived for many years in Italy, and the Italian humanist and later bishop, Ambrogio Caterino Politi.

Machiavelli's ideas had a profound impact on political leaders throughout the modern west, helped by the new technology of the printing press. During the first generations after Machiavelli, his main influence was in non-republican governments. Pole reported that The Prince was spoken of highly by Thomas Cromwell in England and had influenced Henry VIII in his turn towards Protestantism, and in his tactics, for example during the Pilgrimage of Grace.[168] A copy was also possessed by the Catholic king and emperor Charles V.[169] In France, after an initially mixed reaction, Machiavelli came to be associated with Catherine de' Medici and the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. As Bireley (1990:17) reports, in the 16th century, Catholic writers "associated Machiavelli with the Protestants, whereas Protestant authors saw him as Italian and Catholic". In fact, he was apparently influencing both Catholic and Protestant kings.[170]

One of the most important early works dedicated to criticism of Machiavelli, especially The Prince, was that of the Huguenot, Innocent Gentillet, whose work commonly referred to as Discourse against Machiavelli or Anti Machiavel was published in Geneva in 1576.[171] He accused Machiavelli of being an atheist and accused politicians of his time by saying that his works were the "Koran of the courtiers", that "he is of no reputation in the court of France which hath not Machiavel's writings at the fingers ends".[172] Another theme of Gentillet was more in the spirit of Machiavelli himself: he questioned the effectiveness of immoral strategies (just as Machiavelli had himself done, despite also explaining how they could sometimes work). This became the theme of much future political discourse in Europe during the 17th century. This includes the Catholic Counter Reformation writers summarised by Bireley: Giovanni Botero, Justus Lipsius, Carlo Scribani, Adam Contzen, Pedro de Ribadeneira, and Diego de Saavedra Fajardo.[173] These authors criticized Machiavelli, but also followed him in many ways. They accepted the need for a prince to be concerned with reputation, and even a need for cunning and deceit, but compared to Machiavelli, and like later modernist writers, they emphasized economic progress much more than the riskier ventures of war. These authors tended to cite Tacitus as their source for realist political advice, rather than Machiavelli, and this pretence came to be known as "Tacitism".[174] "Black tacitism" was in support of princely rule, but "red tacitism" arguing the case for republics, more in the original spirit of Machiavelli himself, became increasingly important. Cardinal Reginald Pole read The Prince while he was in Italy, and on which he gave his comments.[175] Frederick the Great, king of Prussia and patron of Voltaire, wrote Anti-Machiavel, with the aim of rebutting The Prince.[176]

Modern materialist philosophy developed in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, starting in the generations after Machiavelli. Modern political philosophy tended to be republican, but as with the Catholic authors, Machiavelli's realism and encouragement of innovation to try to control one's own fortune were more accepted than his emphasis upon war and factional violence. Not only was innovative economics and politics a result, but also modern science, leading some commentators to say that the 18th century Enlightenment involved a "humanitarian" moderating of Machiavellianism.[177]

The importance of Machiavelli's influence is notable in many important figures in this endeavour, for example Bodin,[178] Francis Bacon,[179] Algernon Sidney,[180] Harrington, John Milton,[181] Spinoza,[182] Rousseau, Hume,[183] Edward Gibbon, and Adam Smith. Although he was not always mentioned by name as an inspiration, due to his controversy, he is also thought to have been an influence for other major philosophers, such as Montaigne,[184] Descartes,[185] Hobbes, Locke[186] and Montesquieu.[187][188] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who is associated with very different political ideas, viewed Machiavelli's work as a satirical piece in which Machiavelli exposes the faults of a one-man rule rather than exalting amorality.

In the seventeenth century it was in England that Machiavelli's ideas were most substantially developed and adapted, and that republicanism came once more to life; and out of seventeenth-century English republicanism there were to emerge in the next century not only a theme of English political and historical reflection – of the writings of the Bolingbroke circle and of Gibbon and of early parliamentary radicals – but a stimulus to the Enlightenment in Scotland, on the Continent, and in America.[189]

Scholars have argued that Machiavelli was a major indirect and direct influence upon the political thinking of the Founding Fathers of the United States due to his overwhelming favouritism of republicanism and the republican type of government. According to John McCormick, it is still very much debatable whether or not Machiavelli was "an advisor of tyranny or partisan of liberty."[190] Benjamin Franklin, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson followed Machiavelli's republicanism when they opposed what they saw as the emerging aristocracy that they feared Alexander Hamilton was creating with the Federalist Party.[191] Hamilton learned from Machiavelli about the importance of foreign policy for domestic policy, but may have broken from him regarding how rapacious a republic needed to be in order to survive.[192][193] George Washington was less influenced by Machiavelli.[194]

The Founding Father who perhaps most studied and valued Machiavelli as a political philosopher was John Adams, who profusely commented on the Italian's thought in his work, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America.[195] In this work, John Adams praised Machiavelli, with Algernon Sidney and Montesquieu, as a philosophic defender of mixed government. For Adams, Machiavelli restored empirical reason to politics, while his analysis of factions was commendable. Adams likewise agreed with the Florentine that human nature was immutable and driven by passions. He also accepted Machiavelli's belief that all societies were subject to cyclical periods of growth and decay. For Adams, Machiavelli lacked only a clear understanding of the institutions necessary for good government.[195]

Machiavelli's approach has been compared to the Realpolitik of figures such as Otto von Bismarck.[196]

20th century

[edit]The 20th-century Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci drew great inspiration from Machiavelli's writings on ethics, morals, and how they relate to the State and revolution in his writings on Passive Revolution, and how a society can be manipulated by controlling popular notions of morality.[197]

Joseph Stalin read The Prince and annotated his own copy.[198]

In the 20th century there was also renewed interest in Machiavelli's play La Mandragola (1518), which received numerous stagings, including several in New York, at the New York Shakespeare Festival in 1976 and the Riverside Shakespeare Company in 1979, as a musical comedy by Peer Raben in Munich's Anti Theatre in 1971, and at London's National Theatre in 1984.[199]

"Machiavellian"

[edit]

Machiavelli's works are sometimes even said to have contributed to the modern negative connotations of the words politics and politician,[200] and it is sometimes thought that it is because of him that Old Nick became an English term for the Devil.[201] The adjective Machiavellian became a term describing a form of politics that is "marked by cunning, duplicity, or bad faith".[202] The word Machiavellianism is also a term used in political discussions, often as a byword for bare-knuckled political realism.[203][204][205]

Scholars often point to other themes within his works. For example, J. G. A. Pocock (1975) saw him as a major source of the republicanism that spread throughout England and North America in the 17th and 18th centuries and Leo Strauss (1958), whose view of Machiavelli is quite different in many ways, had similar remarks about Machiavelli's influence on republicanism and argued that even though Machiavelli was a teacher of evil he had a "grandeur of vision" that led him to advocate immoral actions. Whatever his intentions, which are still debated today, he has become associated with a particular type of political action and thinking which justifies unsavory conduct in government.[206] For example, Leo Strauss (1987, p. 297) wrote:

Machiavelli is the only political thinker whose name has come into common use for designating a kind of politics, which exists and will continue to exist independently of his influence, a politics guided exclusively by considerations of expediency, which uses all means, fair or foul, iron or poison, for achieving its ends – its end being the aggrandizement of one's country or fatherland – but also using the fatherland in the service of the self-aggrandizement of the politician or statesman or one's party.

In popular culture

[edit]Due to Machiavelli's popularity, he has been featured in various ways in cultural depictions. In English Renaissance theatre (Elizabethan and Jacobian), the term "Machiavel" (from 'Nicholas Machiavel', an "anglicization" of Machiavelli's name based on French) was used for a stock antagonist that resorted to ruthless means to preserve the power of the state, and is now considered a synonym of "Machiavellian".[207][208][209]

Christopher Marlowe's play The Jew of Malta (c. 1589) contains a prologue by a character called Machiavel, a Senecan ghost based on Machiavelli.[210] Machiavel expresses the cynical view that power is amoral, saying:

"I count religion but a childish toy,

And hold there is no sin but ignorance."

Shakespeare's titular character, Richard III, refers to Machiavelli in Henry VI, Part III, as the "murderous Machiavel".[211]

Works

[edit]Political and historical works

[edit]

- Discorso sopra le cose di Pisa (1499)

- Del modo di trattare i popoli della Valdichiana ribellati (1502)

- Descrizione del modo tenuto dal Duca Valentino nello ammazzare Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, il Signor Pagolo e il duca di Gravina Orsini (1502) – A Description of the Methods Adopted by the Duke Valentino when Murdering Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, the Signor Pagolo, and the Duke di Gravina Orsini

- Discorso sopra la provisione del danaro (1502) – A discourse about the provision of money.

- Ritratti delle cose di Francia (1510) – Portrait of the affairs of France.

- Ritratto delle cose della Magna (1508–1512) – Portrait of the affairs of Germany.

- The Prince (1513)

- Discourses on Livy (1517)

- Dell'Arte della Guerra (1519–1520) – The Art of War, high military science.

- Discorso sopra il riformare lo stato di Firenze (1520) – A discourse about the reforming of Florence.

- Sommario delle cose della citta di Lucca (1520) – A summary of the affairs of the city of Lucca.

- The Life of Castruccio Castracani of Lucca (1520) – Vita di Castruccio Castracani da Lucca, a short biography.

- Istorie Fiorentine (1520–1525) – Florentine Histories, an eight-volume history of the city-state Florence, commissioned by Giulio de' Medici, later Pope Clement VII.

Fictional works

[edit]| Part of the Politics series on |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Besides being a statesman and political scientist, Machiavelli also translated classical works, and was a playwright (Clizia, Mandragola), a poet (Sonetti, Canzoni, Ottave, Canti carnascialeschi), and a novelist (Belfagor arcidiavolo).

Some of his other work:

- Decennale primo (1506) – a poem in terza rima.

- Decennale secondo (1509) – a poem.

- Andria or The Girl from Andros (1517) – a semi-autobiographical comedy, adapted from Terence.[212]

- Mandragola (1518) – The Mandrake – a five-act prose comedy, with a verse prologue.

- Clizia (1525) – a prose comedy.

- Belfagor arcidiavolo (1515) – a novella.

- Asino d'oro (1517) – The Golden Ass is a terza rima poem, a new version of the classic work by Apuleius.

- Frammenti storici (1525) – fragments of stories.

Other works

[edit]Della Lingua (Italian for "On the Language") (1514), a dialogue about Italy's language is normally attributed to Machiavelli.

Machiavelli's literary executor, Giuliano de' Ricci, also reported having seen that Machiavelli, his grandfather, made a comedy in the style of Aristophanes which included living Florentines as characters, and to be titled Le Maschere. It has been suggested that due to such things as this and his style of writing to his superiors generally, there was very likely some animosity to Machiavelli even before the return of the Medici.[213]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

- ^ /ˈnɪkəloʊ ˌmækiəˈvɛli/ NIK-ə-loh MAK-ee-ə-VEL-ee, US also /- ˌmɑːk-/ - MAHK-;[1][2][3] Italian: [nikkoˈlɔ mmakjaˈvɛlli]; also occasionally rendered in English as Nicholas Machiavel (/ˈmækiəvɛl/ MAK-ee-ə-vel, US also /ˈmɑːk-/ MAHK-).

- ^ The Latin legend reads: TANTO NOMINI NULLUM PAR ELOGIUM ("So great a name (has) no adequate praise" or "No eulogy (would be) a match for such a great name" or "There is no praise equal to so great a name.")

Citations

- ^ "Machiavelli, Niccolò". Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Longman. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "Machievelli, Niccolò". Lexico US English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022.

- ^ "Machiavelli". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Dietz, Mary G.. Machiavelli, Niccolò (1469–1527), 1998, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780415249126-S080-1. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Taylor and Francis

- ^ Berridge, G.R., Lloyd, L. (2012). M. In: Barder, B., Pope, L.E., Rana, K.S. (eds) The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Diplomacy. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137017611_13

- ^ For example: "Niccolo Machiavelli – Italian statesman and writer". 17 June 2023. and "Niccolò Machiavelli". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ^ For example: Smith, Gregory B. (2008). Between Eternities: On the Tradition of Political Philosophy, Past, Present, and Future. Lexington Books. p. 65. ISBN 978-0739120774., Whelan, Frederick G. (2004). Hume and Machiavelli: Political Realism and Liberal Thought. Lexington Books. p. 29. ISBN 978-0739106310., Strauss (1988). What is Political Philosophy? And Other Studies. University of Chicago Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0226777139.

- ^ Najemy 1993, p. missing

- ^ "Niccolo Machiavelli". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ Cassirer, Ernst (1974) [January 1946]. The Myth of the State. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-00036-7.

- ^ For example, The Prince chap. 15, and The Discourses Book I, chapter 9

- ^ Strauss, Leo; Cropsey, Joseph (2012). History of Political Philosophy. University of Chicago Press. p. 297. ISBN 978-0226924717.

- ^ Mansfield, Harvey C. (1998). Machiavelli's Virtue. University of Chicago Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0226503721.

- ^ Giorgini, Giovanni (2013). "Five Hundred Years of Italian Scholarship on Machiavelli's Prince". Review of Politics. 75 (4): 625–640. doi:10.1017/S0034670513000624. ISSN 0034-6705. S2CID 146970196.

- ^ Strauss, Leo (2014). Thoughts on Machiavelli. University of Chicago Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0226230979.

- ^ Harvey Mansfield and Nathan Tarcov, "Introduction to the Discourses". In their translation of the Discourses on Livy

- ^ Theodosiadis, Michail (June–August 2021). "From Hobbes and Locke to Machiavelli's virtù in the political context of meliorism: popular eucosmia and the value of moral memory". Polis Revista. 11: 25–60.

- ^ Berlin, Isaiah (31 December 2012). The Proper Study of Mankind: An Anthology of Essays. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4464-9695-4.

- ^ de Grazia (1989)

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Nederman, Cary J. (December 2012). Machiavelli: A Beginner's Guide. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-78074-164-2.

- ^ Black, Robert (12 September 2022). Machiavelli: From Radical to Reactionary. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-614-1.

- ^ Maurizio Viroli, Niccolò's Smile: A Biography of Machiavelli (2000), ch 1

- ^ Niccolo Machiavelli Biography – Life of Florentine Republic Official, 13 December 2013

- ^ "Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527)". IEP. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Connell, William J. (10 September 2002). Society and Individual in Renaissance Florence. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92822-0.

- ^ Ridolfi, Roberto (2013). The Life of Niccolò Machiavelli. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1135026615.

- ^ Ridolfi, Roberto (17 June 2013). The Life of Niccolò Machiavelli. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-02661-5.

- ^ Campbell, Gordon (2003). The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-172779-5.

- ^ Viroli, Niccolo's Smile, pg 28, 29

- ^ Guarini (1999:21)

- ^ "Machiavèlli, Niccolò nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Meyer, G. J. (2013). The Borgias: The Hidden History. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-345-52691-5.

- ^ Harvey Mansfield's entry about Machiavelli on Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ "MACHIAVELLI, Niccolò - Enciclopedia".

- ^ "PETRUCCI, Pandolfo - Enciclopedia".

- ^ Machiavelli 1981, p. 136, notes.

- ^ Ridolfi, pg 52

- ^ Ridolfi, pg 52-53

- ^ Ridolfi, pg 52

- ^ a b Viroli, Maurizio (2002). Niccolo's Smile: A Biography of Machiavelli. Macmillan. pp. 81–86. ISBN 978-0374528003.

- ^ This point is made especially in The Prince, Chap XII

- ^ Viroli, Maurizio (2002). Niccolo's Smile: A Biography of Machiavelli. Macmillan. p. 105. ISBN 978-0374528003.

- ^ Elmer, Peter; Webb, Nick; Wood, Roberta; Webb, Nicholas (January 2000). The Renaissance in Europe: An Anthology. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08222-3.

- ^ Zuckert, Catherine H. (31 May 2024). Machiavelli's Politics. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-43494-0.

- ^ Skinner, Quentin (2000). Machiavelli: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0191540349.

- ^ a b Machiavelli 1981, p. 3, intro.

- ^ Bartlett, Kenneth (15 November 2019). The Renaissance in Italy: A History. Hackett. ISBN 978-1-62466-820-3.

- ^ Niccolò Machiavelli (1996), Machiavelli and his friends: Their personal correspondence, Northern Illinois University Press, translated and edited by James B. Atkinson and David Sices.

- ^ Najemy 1993, p. 1

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (September 1998). The Prince: Second Edition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50043-0.

- ^ Joshua Kaplan, "Political Theory: The Classic Texts and their Continuing Relevance," The Modern Scholar (14 lectures in the series; lecture #7 / disc 4), 2005.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (27 February 2009). Discourses on Livy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50033-1.

- ^ Vivanti, Corrado (8 October 2019). Niccolò Machiavelli: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-19689-3.

- ^ Black, Robert (20 November 2013). Machiavelli. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-69957-6.

- ^ "Niccolo Machiavelli | Beliefs, Books, the Prince, Philosophy, Accomplishments, & Facts | Britannica".

- ^ Lynch, Christopher (15 December 2023). Machiavelli on War. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-7304-4.

- ^ Sullivan, Vickie B. (1 January 2000). The Comedy and Tragedy of Machiavelli: Essays on the Literary Works. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08797-0.

- ^ Niccolò Machiavelli - Renaissance, Politics, Italy | Britannica,

Now that Florence had cast off the Medici, Machiavelli hoped to be restored to his old post at the chancery. But the few favours that the Medici had doled out to him caused the supporters of the free republic to look upon him with suspicion. Denied the post, he fell ill and died within a month.

- ^ Viroli, M. (2002). Niccolò's Smile: A Biography of Machiavelli. Macmillan. pg.256-259

- ^ Black, Robert (20 November 2013). Machiavelli. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-69958-3.

- ^ "Even such men as Malatesta and Machiavelli, after spending their lives in estrangement from the Church, sought on their deathbeds her assistance and consolations. Both made good confessions and received the Holy Viaticum." – Ludwig von Pastor, History of the Popes, Vol. 5, p. 137.

- ^ Black, Robert (2013). Machiavelli. Routledge. p. 283. ISBN 978-1317699583.

- ^ Clark, Robert (7 October 2008). Dark Water: Flood and Redemption in Florence--The City of Masterpieces. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-52834-4.

- ^ Zuckert, Catherine H. (2017). Machiavelli's Politics. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226434803.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolo (1984). The Prince. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 0-19-281602-0.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (1532). The Prince. Italy. pp. 120–121.

- ^ Machiavelli, The Prince, Chapter III

- ^ Mansfield, Harvey C. (25 February 1998). Machiavelli's Virtue. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50372-1.

- ^ Rahe, Paul A. (14 November 2005). Machiavelli's Liberal Republican Legacy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-44833-8.

- ^ The Prince, Chapter XVIII, "In What Mode Should Faith Be Kept By Princes"

- ^ The Prince. especially Chapters 3, 5 and 8

- ^ Skinner, Quentin (12 October 2000). Machiavelli: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191540349.

- ^ Strauss (1958, pp. 12)

- ^ Kanzler, Peter (2020). The Prince (1532), The Leviathan (1651), The Two Treatises of Government (1689), The Constitution of Pennsylvania (1776). Peter Kanzler. p. 22. ISBN 978-1716844508.

- ^ Scott, John T. (31 March 2016). The Routledge Guidebook to Machiavelli's the Prince. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-53673-4.

- ^ Landon, W. J. (2005). Politics, Patriotism and Language: Niccolò Machiavelli's" secular Patria" and the Creation of an Italian National Identity (Vol. 57). Peter Lang.

- ^ Forde, Steven (1995). "International Realism and the Science of Politics: Thucydides, Machiavelli, and Neorealism". International Studies Quarterly. 39 (2): 141–160. doi:10.2307/2600844. JSTOR 2600844.

- ^ Newell, W. R. (1988). "Machiavelli and Xenophon on Princely Rule: A Double-Edged Encounter". The Journal of Politics. 50 (1): 108–130. doi:10.2307/2131043. JSTOR 2131043.

- ^ Mansfield, Harvey C. (21 September 2023). Machiavelli's Effectual Truth: Creating the Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-32016-0.

- ^ Discourse on Political Economy: opening pages.

- ^ Berlin, Isaiah. "The Originality of Machiavelli" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Connell, William J.; Machiavelli, Niccolo (5 August 2019). The Prince: With Related Documents. Macmillan Higher Education. ISBN 978-1-319-32840-5.

- ^ This point made most notably by Strauss (1958).

- ^ Mansfield, Harvey C. (1998). Machiavelli's Virtue. University of Chicago Press. pp. 228–229. ISBN 978-0226503721.

- ^ Thomas, Peter D. (2017). "The Modern Prince". History of Political Thought. 38 (3): 523–544. JSTOR 26210463.

- ^ Mansfield, Harvey C. (2001). Machiavelli's New Modes and Orders: A Study of the Discourses on Livy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226503707.

- ^ "Discourses on Livy: Book 1, Chapter 18". www.constitution.org. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (27 February 2009). Discourses on Livy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50033-1.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (2009). Discourses on Livy: Book One, Chapter 9. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226500331.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (2009). Discourses on Livy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226500331.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (2009). Discourses on Livy: Book One, Chapter 16. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226500331.

- ^ Rahe, Paul A. (2005). Machiavelli's Liberal Republican Legacy. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1139448338.

- ^ Hulliung, Mark (2017). Citizen Machiavelli. Routledge. ISBN 978-1351528481.

- ^ Pocock (1975, pp. 183–219)

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (1901). "History of Florence and of the Affairs of Italy: From the Earliest Times to the Death of Lorenzo the Magnificent".

- ^ Connell, William J. (10 September 2002). Society and Individual in Renaissance Florence. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92822-0.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (1988). Florentine Histories. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00863-9.

- ^ "Florentine Histories | work by Machiavelli | Britannica".

- ^ Clarke, Michelle T. (8 March 2018). Machiavelli's Florentine Republic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-12550-6.

- ^ a b Harvey C. Mansfield, Machiavelli's Virtue, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1996, (a&b)194, (c)191 & 196.

- ^ a b c d e f Fischer (2000)

- ^ Interpreting Modern Political Philosophy: From Machiavelli to Marx, pg. 40

- ^ Mansfield, Harvey C. (1998). Machiavelli's Virtue. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226503721.

- ^ Mansfield, Machiavelli's Virtue, pg. ix (Introduction)

- ^ Rohlf, Michael (December 2017). The Modern Turn. CUA Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-3005-4.

- ^ Gilbert, A. (1938). "Machiavelli's Prince and Its Forerunners: The Prince as a Typical Book de Regimine Principum".

- ^ Gilbert, Allan (1938), Machiavelli's Prince and Its Forerunners, Duke University Press, pg 22

- ^ Skinner, Quentin (1978). The Foundations of Modern Political Thought: Volume 1, The Renaissance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521293372.

- ^ Pocock, J. G. A. (2016). The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400883516.

- ^ Berlin, I. (2014). ‘The Originality of Machiavelli'. In Reading Political Philosophy (pp. 43-58). Routledge.

- ^ New Modes and Orders, p. 391

- ^ Harvey Mansfield and Nathan Tarcov, "Introduction to the Discourses". In their translation of the Discourses on Livy

- ^ Rohlf, Michael (December 2017). The Modern Turn. CUA Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-3005-4.

- ^ Niccolò Machiavelli, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ a b Strauss (1958)

- ^ Paul Anthony Rahe, Against throne and altar: Machiavelli and political theory under the English Republic (2008), p. 282.

- ^ Jack Donnelly, Realism and International Relations (2000), p. 68.

- ^ Black, Robert (12 September 2022). Machiavelli: From Radical to Reactionary. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-614-1.

- ^ Sullivan, Vickie B. (15 January 2020). Machiavelli's Three Romes: Religion, Human Liberty, and Politics Reformed. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-4785-4.

- ^ Newell, W. R. (1988). "Machiavelli and Xenophon on Princely Rule: A Double-Edged Encounter". The Journal of Politics. 50 (1): 108–130. doi:10.2307/2131043. JSTOR 2131043.

- ^ Leo Strauss, Joseph Cropsey, History of Political Philosophy (1987), p. 300.

- ^ Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, Chap 17.

- ^ "Niccolò Machiavelli, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy".

- ^ Strauss, Leo (1953). Natural Right and History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77694-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Machiavelli on the problem of our impure beginnings | Aeon Essays".

- ^ Strauss, Leo (2014). Thoughts on Machiavelli. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226230979.

- ^ Strauss, Leo. Leo Strauss "Thoughts On Machiavelli". p. 9.

- ^ Carritt, E. F. (1949). Benedetto Croce My Philosophy.

- ^ Cassirer, Ernst (1974) [1961]. The Myth of the State. New Haven, Connecticut; London, England: Yale University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-300-00036-8.

- ^ Althusser, Louis (1999). Machiavelli and Us. Verso. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-85984-711-4.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (2009). Discourses on Livy. University of Chicago Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0226500331.

- ^ Discourses on Livy, Book II chap. 2

- ^ Mansfield, Harvey C. (25 February 1998). Machiavelli's Virtue. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226503721.

- ^ Hulliung, Mark (5 July 2017). Citizen Machiavelli. Routledge. ISBN 9781351528481.

- ^ Skinner, Quentin (30 November 1978). The Foundations of Modern Political Thought: Volume 1, the Renaissance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29337-2.

- ^ Skinner, Q. (2017). Machiavelli and the misunderstanding of princely virtù. Machiavelli on Liberty and Conflict, 139-163.

- ^ Mansfield, Harvey C. (25 February 1998). Machiavelli's Virtue. University of Chicago Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-226-50372-1.

- ^ Mansfield (1993)

- ^ Najemy 1993, p. 203-204.

- ^ "Niccolò Machiavelli". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2025.

- ^ Johnston, David; Urbinati, Nadia; Vergara, Camila (31 May 2024). Machiavelli on Liberty & Conflict. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-42944-1.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (2009). Discourses on Livy, Book 1, Chapter 11–15. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226500331.

- ^ Machiavelli, Niccolò (2010). The Prince: Second Edition. University of Chicago Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0226500508.

- ^ Pangle, Thomas L.; Burns, Timothy W. (2015). The Key Texts of Political Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00607-2.

- ^ Especially in the Discourses III.30, but also The Prince Chap.VI

- ^ Strauss (1987, p. 314)

- ^ See for example Strauss (1958, p. 206).

- ^ Parsons, W. B. (2016). Machiavelli's gospel: The critique of Christianity in the prince. Boydell & Brewer.

- ^ Viroli, Maurizio (July 2010). Machiavelli's God. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3503-4.

- ^ Grazia, Sebastian De (13 January 1994). Machiavelli in Hell. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 978-0-679-74342-2.

- ^ Tarcov, Nathan (2014). "Machiavelli's Critique of Religion". Social Research: An International Quarterly. 81: 193–216. doi:10.1353/sor.2014.0005.

- ^ Sullivan, Vickie B. (15 January 2020). Machiavelli's Three Romes: Religion, Human Liberty, and Politics Reformed. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-4786-1.

- ^ Vavouras, Elias; Theodosiadis, Michail (October 2024). "The Concept of Religion in Machiavelli: Political Methodology, Propaganda and Ideological Enlightenment". Religions. 15 (10): 1203. doi:10.3390/rel15101203. ISSN 2077-1444.

- ^ Strauss (1958, p. 231)

- ^ Hexter, J. H. (1957). "Il principe and lo stato". Studies in the Renaissance. 4: 113–138. doi:10.2307/2857143. JSTOR 2857143.

- ^ Mansfield, Harvey C. (1983). "On the Impersonality of the Modern State: A Comment on Machiavelli's Use of Stato". The American Political Science Review. 77 (4): 849–857. doi:10.2307/1957561. JSTOR 1957561.

- ^ "The prince of the people: Machiavelli was no 'Machiavellian' | Aeon Essays".

- ^ "Machiavelli, Niccolò | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy".

- ^ McCormick, John P. (2015). "Machiavelli's Inglorious Tyrants: On Agathocles, Scipio and Unmerited Glory". History of Political Thought. 36 (1): 29–52. JSTOR 26226962.

- ^ Sullivan, Vickie (5 June 2024). Inglis, Jeff (ed.). "500 years ago, Machiavelli warned the public not to get complacent in the face of self-interested charismatic figures". doi:10.64628/AAI.sqftemd5k.

- ^ Pocock, J. G. A. The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975.

- ^ Hankins, James (2000). Renaissance Civic Humanism: Reappraisals and Reflections. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54807-6.

- ^ Pangle, Thomas L. (15 October 1990). The Spirit of Modern Republicanism: The Moral Vision of the American Founders and the Philosophy of Locke. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-64547-6.

- ^ Hulliung, Mark (5 July 2017). Citizen Machiavelli. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-52848-1.

- ^ Hörnqvist, Mikael (25 November 2004). Machiavelli and Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45634-0.

- ^ Bireley, Robert (1990), The Counter Reformation Prince, p. 14.

- ^ Bireley (1990:15)

- ^ Haitsma Mulier (1999:248)

- ^ While Bireley focuses on writers in the Catholic countries, Haitsma Mulier (1999) makes the same observation, writing with more of a focus upon the Protestant Netherlands.

- ^ The first English edition was A Discourse upon the meanes of wel governing and maintaining in good peace, a Kingdome, or other principalitie, translated by Simon Patericke.

- ^ Bireley (1990:17)

- ^ Bireley (1990:18)

- ^ Bireley (1990:223–230)

- ^ Benner, Erica (28 November 2013). Machiavelli's Prince: A New Reading. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191003929.

- ^ "Anti-Machiavel | treatise by Frederick the Great". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Kennington (2004), Rahe (2006)

- ^ Bireley (1990:17): "Jean Bodin's first comments, found in his Method for the Easy Comprehension of History, published in 1566, were positive."

- ^ Bacon wrote: "We are much beholden to Machiavelli and other writers of that class who openly and unfeignedly declare or describe what men do, and not what they ought to do." "II.21.9", Of the Advancement of Learning. See Kennington (2004) Chapter 4.

- ^ Rahe (2006) chapter 6.

- ^ Worden (1999)

- ^ "Spinoza's Political Philosophy". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ Danford "Getting Our Bearings: Machiavelli and Hume" in Rahe (2006).

- ^ Schaefer (1990)

- ^ Kennington (2004), chapter 11.

- ^ Barnes Smith "The Philosophy of Liberty: Locke's Machiavellian Teaching" in Rahe (2006).

- ^ Carrese "The Machiavellian Spirit of Montesquieu's Liberal Republic" in Rahe (2006)

- ^ Shklar (1999)

- ^ Worden (1999)

- ^ John P. McCormick, Machiavellian democracy (Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 23.

- ^ Rahe (2006)

- ^ Walling "Was Alexander Hamilton a Machiavellian Statesman?" in Rahe (2006).

- ^ Harper (2004)

- ^ Spalding "The American Prince? George Washington's Anti-Machiavellian moment" in Rahe (2006)

- ^ a b Thompson (1995)

- ^ Pflanze, Otto (1958). "Bismarck's "Realpolitik"". The Review of Politics. 20 (4): 492–514. doi:10.1017/S0034670500034185. ISSN 0034-6705. JSTOR 1404857. S2CID 144663704.

- ^ Marcia Landy, "Culture and Politics in the work of Antonio Gramsci," 167–188, in Antonio Gramsci: Intellectuals, Culture, and the Party, ed. James Martin (New York: Routledge, 2002).

- ^ Service, Robert. Stalin: A Biography, p.10.

- ^ Review by Jann Racquoi, Heights/Inwood Press of North Manhattan, 14 March 1979.

- ^ Bireley (1990, p. 241)

- ^ Fischer (2000, p. 94)

- ^ "Definition of MACHIAVELLIAN". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ Rahe, Paul A. (2005). Machiavelli's Liberal Republican Legacy. Cambridge University Press. p. xxxvi. ISBN 978-1139448338.

- ^ Meinecke, Friedrich (1957). Machiavellism: The Doctrine of Raison d'État and Its Place in Modern History. Yale University Press. p. 36.

- ^ "Political Realism in International Relations". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2023.

- ^ Maritain, Jacques (1942). "The End of Machiavellianism". The Review of Politics. 4: 1–33. doi:10.1017/S0034670500003235.

- ^ Kahn, V. (1994). Machiavellian rhetoric: From the counter-reformation to Milton. Princeton University Press.

- ^ "Machiavel". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ "MACHIAVEL English Definition and Meaning | Lexico.com". Lexico Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ "Jew of Malta, The by MARLOWE, Christopher". Player FM. 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ "Henry VI, Part 3 - Entire Play | Folger Shakespeare Library".

- ^ "First-time Machiavelli translation debuts at Yale". yaledailynews.com. 18 April 2012.

- ^ Godman (1998, p. 240). Also see Black (1999, pp. 97–98)

Sources

[edit]- Machiavelli, Niccolò (1981). The Prince and Selected Discourses. Translated by Daniel Donno. New York: Bantam Classic Books. ISBN 0553212273.

- Haitsma Mulier, Eco (1999). "A controversial republican". In Bock, Gisela; Skinner, Quentin; Viroli, Maurizio (eds.). Machiavelli and Republicanism. Cambridge University Press.

- Harper, John Lamberton (2004). American Machiavelli: Alexander Hamilton and the Origins of US Foreign Policy. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521834858.

- Shklar, J. (1999). "Montesquieu and the new republicanism". In Bock, Gisela; Skinner, Quentin; Viroli, Maurizio (eds.). Machiavelli and Republicanism. Cambridge University Press.

- Strauss, Leo (1958), Thoughts on Machiavelli, University of Chicago Press

- Worden, Blair (1999). "Milton's republicanism and the tyranny of heaven". In Bock, Gisela; Skinner, Quentin; Viroli, Maurizio (eds.). Machiavelli and Republicanism. Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

[edit]Biographies

[edit]- Baron, Hans (April 1961). "Machiavelli: The Republican Citizen and the Author of 'the Prince'". The English Historical Review. 76 (299): 217–253. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXVI.CCXCIX.217. JSTOR 557541.

- Black, Robert. Machiavelli: From Radical to Reactionary. London: Reaktion Books (2022)

- Burd, L. A., "Florence (II): Machiavelli" in Cambridge Modern History (1902), vol. I, ch. vi. pp. 190–218 online Google edition

- Capponi, Niccolò. An Unlikely Prince: The Life and Times of Machiavelli (Da Capo Press; 2010) 334 pages

- Celenza, Christopher S. Machiavelli: A Portrait (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2015) 240 pages. ISBN 978-0674416123

- Godman, Peter (1998), From Poliziano to Machiavelli: Florentine Humanism in the High Renaissance, Princeton University Press

- de Grazia, Sebastian (1989), Machiavelli in Hell, Knopf Doubleday Publishing, ISBN 978-0679743422, an intellectual biography that won the Pulitzer Prize; excerpt and text search Archived 9 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Hale, J. R. Machiavelli and Renaissance Italy (1961) online edition Archived 19 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Hulliung, Mark. Citizen Machiavelli (Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge, 1983)

- Lee, Alexander. Machiavelli: His Life and Times (London: Picador, 2020)

- Oppenheimer, Paul. Machiavelli: A Life Beyond Ideology (London; New York: Continuum, 2011) ISBN 978-1847252210

- Ridolfi, Roberto. The Life of Niccolò Machiavelli (1963)

- Schevill, Ferdinand. Six Historians (1956), pp. 61–91

- Skinner, Quentin. Machiavelli, in Past Masters series. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1981. pp. vii, 102. ISBN 0192875167 pbk.

- Skinner, Quentin. Machiavelli: A Very Short Introduction (2d ed., 2019) ISBN 978-0198837572 pbk.

- Unger, Miles J. Machiavelli: A Biography (Simon & Schuster, 2011)

- Villari, Pasquale. The Life and Times of Niccolò Machiavelli (2 vols. 1892) (Vol 1; Vol 2)

- Viroli, Maurizio (2000), Niccolò's Smile: A Biography of Machiavelli, Farrar, Straus & Giroux excerpt and text search Archived 24 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Viroli, Maurizio. Machiavelli (1998) online edition Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Vivanti, Corrado. Niccolò Machiavelli: An Intellectual Biography (Princeton University Press; 2013) 261 pages

Political thought