Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lipase

View on Wikipedia| Lipase | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Pronunciation | /ˈlaɪpeɪs, ˈlaɪpeɪz/ LY-payss, LY-payz | ||||||

| Test of | Pancreatitis | ||||||

| |||||||

Lipase is a class of enzymes that catalyzes the hydrolysis of fats. Some lipases display broad substrate scope including esters of cholesterol, phospholipids, and of lipid-soluble vitamins[1][2] and sphingomyelinases;[3] however, these are usually treated separately from "conventional" lipases. Unlike esterases, which function in water, lipases "are activated only when adsorbed to an oil–water interface".[4] Lipases perform essential roles in digestion, transport and processing of dietary lipids in most, if not all, organisms.

Structure and catalytic mechanism

[edit]Classically, lipases catalyse the hydrolysis of triglycerides:[citation needed]

Lipases are serine hydrolases, i.e. they function by transesterification generating an acyl serine intermediate. Most lipases act at a specific position on the glycerol backbone of a lipid substrate (A1, A2 or A3). For example, human pancreatic lipase (HPL),[5] converts triglyceride substrates found in ingested oils to monoglycerides and two fatty acids.

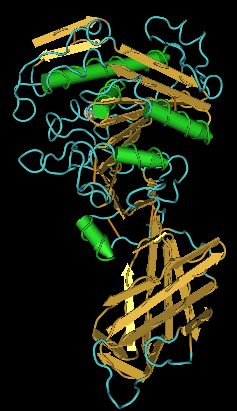

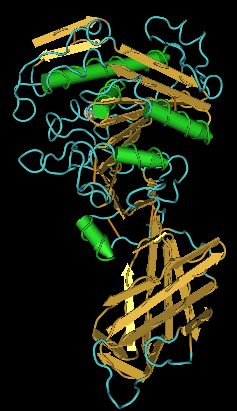

A diverse array of genetically distinct lipase enzymes are found in nature, and they represent several types of protein folds and catalytic mechanisms. However, most are built on an alpha/beta hydrolase fold[6][7][8][9] and employ a chymotrypsin-like hydrolysis mechanism using a catalytic triad consisting of a serine nucleophile, a histidine base, and an acid residue, usually aspartic acid.[10][11]

Physiological distribution

[edit]Lipases are involved in diverse biological processes which range from routine metabolism of dietary triglycerides to cell signaling[12] and inflammation.[13] Thus, some lipase activities are confined to specific compartments within cells while others work in extracellular spaces.

- In the example of lysosomal lipase, the enzyme is confined within an organelle called the lysosome.

- Other lipase enzymes, such as pancreatic lipases, are secreted into extracellular spaces where they serve to process dietary lipids into more simple forms that can be more easily absorbed and transported throughout the body.

- Fungi and bacteria may secrete lipases to facilitate nutrient absorption from the external medium (or in examples of pathogenic microbes, to promote invasion of a new host).

- Certain wasp and bee venoms contain phospholipases that enhance the effects of injury and inflammation delivered by a sting.

- As biological membranes are integral to living cells and are largely composed of phospholipids, lipases play important roles in cell biology.

- Malassezia globosa, a fungus thought to be the cause of human dandruff, uses lipase to break down sebum into oleic acid and increase skin cell production, causing dandruff.[14]

Genes encoding lipases are even present in certain viruses.[15][16]

Some lipases are expressed and secreted by pathogenic organisms during an infection. In particular, Candida albicans has many lipases, possibly reflecting broad-lipolytic activity, which may contribute to the persistence and virulence of C. albicans in human tissue.[17]

Human lipases

[edit]| Name | Gene | Location | Description | Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bile salt-dependent lipase | BSDL | pancreas, breast milk | aids in the digestion of fats[1] | |

| pancreatic lipase | PNLIP | digestive juice | Human pancreatic lipase (HPL) is the main enzyme that breaks down dietary fats in the human digestive system.[5] To exhibit optimal enzyme activity in the gut lumen, PL requires another protein, colipase, which is also secreted by the pancreas.[18] | |

| lysosomal lipase | LIPA | interior space of organelle: lysosome | Also referred to as lysosomal acid lipase (LAL or LIPA) or acid cholesteryl ester hydrolase | Cholesteryl ester storage disease (CESD) and Wolman disease are both caused by mutations in the gene encoding lysosomal lipase.[19] |

| hepatic lipase | LIPC | endothelium | Hepatic lipase acts on the remaining lipids carried on lipoproteins in the blood to regenerate LDL (low density lipoprotein). | – |

| lipoprotein lipase | LPL or "LIPD" | endothelium | Lipoprotein lipase functions in the blood to act on triacylglycerides carried on VLDL (very low density lipoprotein) so that cells can take up the freed fatty acids. | Lipoprotein lipase deficiency is caused by mutations in the gene encoding lipoprotein lipase.[20][21] |

| hormone-sensitive lipase | LIPE | intracellular | – | – |

| gastric lipase | LIPF | digestive juice | Functions in the infant at a near-neutral pH to aid in the digestion of lipids | – |

| endothelial lipase | LIPG | endothelium | – | – |

| pancreatic lipase related protein 2 | PNLIPRP2 or "PLRP2" – | digestive juice | – | – |

| pancreatic lipase related protein 1 | PNLIPRP1 or "PLRP1" | digestive juice | Pancreatic lipase related protein 1 is very similar to PLRP2 and PL by amino acid sequence (all three genes probably arose via gene duplication of a single ancestral pancreatic lipase gene). However, PLRP1 is devoid of detectable lipase activity and its function remains unknown, even though it is conserved in other mammals.[22][23] | - |

| lingual lipase | ? | saliva | Active at gastric pH levels. Optimum pH is about 3.5-6. Secreted by several of the salivary glands (Ebner's glands at the back of the tongue (lingua), the sublingual glands, and the parotid glands) | – |

Other lipases include LIPH, LIPI, LIPJ, LIPK, LIPM, LIPN, MGLL, DAGLA, DAGLB, and CEL.

Uses

[edit]In the commercial sphere, lipases are widely used in laundry detergents. Several thousand tons per year are produced for this role.[4]

Lipases are catalysts for hydrolysis of esters and are useful outside of the cell, a testament to their wide substrate scope and ruggedness. The ester hydrolysis activity of lipases has been well evaluated for the conversion of triglycerides into biofuels or their precursors.[24][25][26][27]

Lipases are chiral, which means that they can be used for the enantioselective hydrolysis prochiral diesters.[28] Several procedures have been reported for applications in the synthesis of fine chemicals.[29][30][31]

Lipases are generally animal sourced, but can also be sourced microbially.[citation needed]

Biomedicine

[edit]Blood tests for lipase may be used to help investigate and diagnose acute pancreatitis and other disorders of the pancreas.[32] Measured serum lipase values may vary depending on the method of analysis.[citation needed]

Lipase assist in the breakdown of fats in those undergoing pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT). It is a component in Sollpura (Liprotamase).[33][34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Lombardo, Dominique (2001). "Bile salt-dependent lipase: its pathophysiological implications". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1533 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1016/S1388-1981(01)00130-5. PMID 11514232.

- ^ Diaz, B.L.; J. P. Arm. (2003). "Phospholipase A(2)". Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 69 (2–3): 87–97. doi:10.1016/S0952-3278(03)00069-3. PMID 12895591.

- ^ Goñi F, Alonso A (2002). "Sphingomyelinases: enzymology and membrane activity". FEBS Lett. 531 (1): 38–46. Bibcode:2002FEBSL.531...38G. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03482-8. PMID 12401200.

- ^ a b Sharma, Rohit; Chisti, Yusuf; Banerjee, Uttam Chand (2001). "Production, purification, characterization, and applications of lipases". Biotechnology Advances. 19 (8): 627–662. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.319.7729. doi:10.1016/S0734-9750(01)00086-6. PMID 14550014. S2CID 18615547.

- ^ a b Winkler FK; D'Arcy A; W Hunziker (1990). "Structure of human pancreatic lipase". Nature. 343 (6260): 771–774. Bibcode:1990Natur.343..771W. doi:10.1038/343771a0. PMID 2106079. S2CID 37423900.

- ^ Winkler FK; D'Arcy A; W Hunziker (1990). "Structure of human pancreatic lipase". Nature. 343 (6260): 771–774. Bibcode:1990Natur.343..771W. doi:10.1038/343771a0. PMID 2106079. S2CID 37423900.

- ^ Schrag J, Cygler M (1997). "Lipases and hydrolase fold". Lipases, Part A: Biotechnology. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 284. pp. 85–107. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(97)84006-2. ISBN 978-0-12-182185-2. PMID 9379946.

- ^ Egmond, M. R.; C. J. van Bemmel (1997). "Impact of structural information on understanding lipolytic function". Lipases, Part A: Biotechnology. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 284. pp. 119–129. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(97)84008-6. ISBN 978-0-12-182185-2. PMID 9379930.

- ^ Withers-Martinez C; Carriere F; Verger R; Bourgeois D; C Cambillau (1996). "A pancreatic lipase with a phospholipase A1 activity: crystal structure of a chimeric pancreatic lipase-related protein 2 from guinea pig". Structure. 4 (11): 1363–74. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00143-8. PMID 8939760.

- ^ Brady, L.; A. M. Brzozowski; Z. S. Derewenda; E. Dodson; G. Dodson; S. Tolley; J. P. Turkenburg; L. Christiansen; B. Huge-Jensen; L. Norskov; et al. (1990). "A serine protease triad forms the catalytic centre of a triacylglycerol lipase". Nature. 343 (6260): 767–70. Bibcode:1990Natur.343..767B. doi:10.1038/343767a0. PMID 2304552. S2CID 4308111.

- ^ Lowe ME (1992). "The catalytic site residues and interfacial binding of human pancreatic lipase". J Biol Chem. 267 (24): 17069–73. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)41893-5. PMID 1512245.

- ^ Spiegel S; Foster D; R Kolesnick (1996). "Signal transduction through lipid second messengers". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 8 (2): 159–67. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(96)80061-5. PMID 8791422.

- ^ Tjoelker LW; Eberhardt C; Unger J; Trong HL; Zimmerman GA; McIntyre TM; Stafforini DM; Prescott SM; PW Gray (1995). "Plasma platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase is a secreted phospholipase A2 with a catalytic triad". J Biol Chem. 270 (43): 25481–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.43.25481. PMID 7592717.

- ^ Genetic Code of Dandruff Cracked – BBC News

- ^ Afonso C, Tulman E, Lu Z, Oma E, Kutish G, Rock D (1999). "The Genome of Melanoplus sanguinipes Entomologists". J Virol. 73 (1): 533–52. doi:10.1128/JVI.73.1.533-552.1999. PMC 103860. PMID 9847359.

- ^ Girod A, Wobus C, Zádori Z, Ried M, Leike K, Tijssen P, Kleinschmidt J, Hallek M (2002). "The VP1 capsid protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 is carrying a phospholipase A2 domain required for virus infectivity". J Gen Virol. 83 (Pt 5): 973–8. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-83-5-973. PMID 11961250.

- ^ Hube B, Stehr F, Bossenz M, Mazur A, Kretschmar M, Schafer W (2000). "Secreted lipases of Candida albicans: cloning, characterisation and expression analysis of a new gene family with at least ten members". Arch. Microbiol. 174 (5): 362–374. Bibcode:2000ArMic.174..362H. doi:10.1007/s002030000218. PMID 11131027. S2CID 2231039.

- ^ Lowe ME (2002). "The triglyceride lipases of the pancreas". J Lipid Res. 43 (12): 2007–16. doi:10.1194/jlr.R200012-JLR200. PMID 12454260.

- ^ Omim – Wolman Disease

- ^ Familial lipoprotein lipase deficiency – Genetics Home Reference

- ^ Gilbert B, Rouis M, Griglio S, de Lumley L, Laplaud P (2001). "Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) deficiency: a new patient homozygote for the preponderant mutation Gly188Glu in the human LPL gene and review of reported mutations: 75 % are clustered in exons 5 and 6". Ann Genet. 44 (1): 25–32. doi:10.1016/S0003-3995(01)01037-1. PMID 11334614.

- ^ Crenon I, Foglizzo E, Kerfelec B, Verine A, Pignol D, Hermoso J, Bonicel J, Chapus C (1998). "Pancreatic lipase-related protein type I: a specialized lipase or an inactive enzyme". Protein Eng. 11 (2): 135–42. doi:10.1093/protein/11.2.135. PMID 9605548.

- ^ De Caro J, Carriere F, Barboni P, Giller T, Verger R, De Caro A (1998). "Pancreatic lipase-related protein 1 (PLRP1) is present in the pancreatic juice of several species". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1387 (1–2): 331–41. doi:10.1016/S0167-4838(98)00143-5. PMID 9748646.

- ^ Gupta R, Gupta N, Rathi P (2004). "Bacterial lipases: an overview of production, purification and biochemical properties". Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 64 (6): 763–81. doi:10.1007/s00253-004-1568-8. PMID 14966663. S2CID 206934353.

- ^ Ban K, Kaieda M, Matsumoto T, Kondo A, Fukuda H (2001). "Whole cell biocatalyst for biodiesel fuel production utilizing Rhizopus oryzae cells immobilized within biomass support particles". Biochem Eng J. 8 (1): 39–43. Bibcode:2001BioEJ...8...39B. doi:10.1016/S1369-703X(00)00133-9. PMID 11356369.

- ^ Harding, K.G; Dennis, J.S; von Blottnitz, H; Harrison, S.T.L (2008). "A life-cycle comparison between inorganic and biological catalysis for the production of biodiesel". Journal of Cleaner Production. 16 (13): 1368–78. Bibcode:2008JCPro..16.1368H. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.07.003.

- ^ Guo Z, Xu X (2005). "New opportunity for enzymatic modification of fats and oils with industrial potentials". Org Biomol Chem. 3 (14): 2615–9. doi:10.1039/b506763d. PMID 15999195.

- ^ Theil, Fritz (1995). "Lipase-Supported Synthesis of Biologically Active Compounds". Chemical Reviews. 95 (6): 2203–2227. doi:10.1021/cr00038a017.

- ^ P. Kalaritis, R. W. Regenye (1990). "Enantiomerically Pure Ethyl (R)- And (S)- 2-Fluorohexanoate by Enzyme-Catalyzed Kinetic Resolution". Org. Synth. 69: 10. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.069.0010.

- ^ Leo A. Paquette, Martyn J. Earle, Graham F. Smith (1996). "(4R)-(+)-tert-Butyldimethylsiloxy-2-cyclopenten-1-one". Org. Synth. 73: 36. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.073.0036.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "(4R)-(+)-tert-BUTYLDIMETHYLSILOXY-2-CYCLOPENTEN-1-ONE". Organic Syntheses. 73: 36. 1996. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.073.0036.

- ^ "Lipase – TheTest". Lab Tests Online. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Anthera Pharmaceuticals – Sollpura." Anthera Pharmaceuticals – Sollpura. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 July 2015. <http://www.anthera.com/pipeline/science/sollpura.html Archived 2015-07-18 at the Wayback Machine>.

- ^ Bustanji, Yasser; Al-Masri, Ihab M; Mohammad, Mohammad; Hudaib, Mohammad; Tawaha, Khaled; Tarazi, Hamada; Alkhatib, Hatim S (2010). "Pancreatic lipase inhibition activity of trilactone terpenes of Ginkgo biloba". Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 26 (4): 453–9. doi:10.3109/14756366.2010.525509. PMID 21028941. S2CID 23597738.

25. Gulzar, Bio-degradation of hydrocarbons using different bacterial and fungal species. Published in international conference on biotechnology and neurosciences. CUSAT (cochin university of science and technology), 2003

External links

[edit]- Lipase at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\text{triglyceride}}+{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} }&\longrightarrow {\text{fatty acid}}+{\text{diacylglycerol}}\\[4pt]{\text{diacylglycerol}}+{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} }&\longrightarrow {\text{fatty acid}}+{\text{monacylglycerol}}\\[4pt]{\text{monacylglycerol}}+{\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} }&\longrightarrow {\text{fatty acid}}+{\text{glycerol}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/15fddd873ef9f78c820d155057b082404f1ae0fb)