Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Grand Prix of Long Beach

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| IndyCar Series | |

|---|---|

| Location | Long Beach, California 33°45′59″N 118°11′34″W / 33.76639°N 118.19278°W |

| Corporate sponsor | Acura (Honda) |

| First race | 1975 |

| First ICS race | 2009 |

| Distance | 177.12 mi (285.05 km) |

| Laps | 90 |

| Previous names | Long Beach Grand Prix (1975) United States Grand Prix West (1976–1983) Toyota Grand Prix of the United States (1980–1981, 1983) Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach (1984–2018) |

| Most wins (driver) | Al Unser Jr. (6) |

| Most wins (team) | Team Penske (7) Ganassi (7) |

| Most wins (manufacturer) | Chassis: Dallara (15) Engine: Honda (18) Tires: Firestone (21) |

| Circuit information | |

| Length | 1.968 mi (3.167 km) |

| Turns | 11 |

| Lap record | 1:05.309 ( |

The Grand Prix of Long Beach (known as Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach since 2019 for naming rights reasons) is an IndyCar Series race held on a street circuit in downtown Long Beach, California. It was the premier race on the CART/Champ Car World Series calendar from 1984 to 2008, with the 2008 race being the final Champ Car series race prior to the formal unification and end of the open-wheel "split" between CART and Indy Racing League (IRL). Since 2009, the race has been part of the unified IndyCar Series.[1][2] The race is typically held in April. It is the second-oldest continuously running event in IndyCar racing behind only the Indianapolis 500, and is considered one of the most prestigious events on the circuit.

The Long Beach Grand Prix is the longest running major street race held in North America. It was started in 1975 as a Formula 5000 race by event founder Christopher Pook, and became a Formula One event in 1976.[3] In an era when turbocharged engines were starting to come to prominence in Formula One, Long Beach remains one of the few circuits used from the time Renault introduced turbos in 1977 until the last Long Beach Grand Prix in 1983 that never once saw a turbo-powered car take victory.

John Watson's win for McLaren in 1983 holds the Formula One record for the lowest ever starting position for a race winner. In a grid consisting of 26 cars, Watson started 22nd in his McLaren-Ford. That same race also saw Watson's teammate (and 1982 Long Beach winner) Niki Lauda finish second after starting 23rd on the grid. René Arnoux, who finished third in his Ferrari 126C2B, was the only driver to ever finish on the Formula One podium at Long Beach driving a turbocharged car.

In 1984, the race switched from a Formula One race to a CART IndyCar event. Support races over the years have included Indy Lights, IMSA, Atlantics, Pirelli World Challenge, Trans-Am Series, Formula D, Stadium Super Trucks, Formula E, and the Toyota Pro/Celebrity Race. Toyota was a sponsor of the event since its beginning and title sponsor from 1980 to 2018,[4] believed to be the longest continuously running sports sponsorship in the U.S.

The Long Beach Grand Prix has been announced since 1978 by Bruce Flanders (and various guest announcers). The Long Beach Grand Prix in April is the single largest event in the city of Long Beach. Attendance for the weekend regularly reaches or exceeds 200,000 people. In 2006, the Long Beach Motorsports Walk of Fame was created to honor selected past winners and key contributors to the sport of auto racing.

Event history

[edit]

The Long Beach Grand Prix was the brainchild of promoter Chris Pook, a former travel agent from England. Pook was inspired by the Monaco Grand Prix, and believed that a similar event had the potential to succeed in the Southern California area. The city of Long Beach was selected, approximately 25 miles (40 km) south of downtown Los Angeles. A waterfront circuit, near the Port of Long Beach was laid out on city streets, and despite the area at the time being mostly a depressed, industrial port city, the first event drew 30,000 fans. The inaugural race was held in September 1975 as part of the Formula 5000 series.[5][6]

In 1976, the United States Grand Prix West was created, providing two grand prix races annually in the United States for a time. Long Beach became a Formula One event for 1976 and the race was moved to March or April. Meanwhile, the United States Grand Prix East at Watkins Glen International was experiencing a noticeably steady decline. Despite gaining a reputation of being demanding and rough on equipment, Long Beach almost immediately gained prominence owing much to its pleasant weather, picturesque setting, and close proximity to Los Angeles and the glitzy Hollywood area.[5][6][7] When Watkins Glen was dropped from the Formula One calendar after 1980, the now-established Long Beach began to assume an even more prominent status.

Despite exciting races and strong attendance, the event was not financially successful as a Formula One event. The promoter was risking a meager $100,000 profit against a $6–7 million budget. Fearing that one poor running could bankrupt the event, Pook convinced city leaders to change the race to a CART Indy car event beginning in 1984. In short time, the event grew to prominence on the Indy car circuit and has been credited with triggering a renaissance in the city of Long Beach. The race was used to market the city, and in the years since the race's inception, many dilapidated and condemned buildings have been replaced with high-rise hotels and tourist attractions.[5][6]

The event served as a CART/Champ Car race from 1984 to 2008, then became an IndyCar Series race event in 2009. The 2017 race was the 43rd running, and the 34th consecutive as an IndyCar race, one of the longest continuously running events in the history of American open-wheel car racing. On three occasions (1984, 1985 and 1987) the race served as the CART season opener. In seven separate seasons (1986, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1992, 1993 and 1994), it served as the final race before the Indianapolis 500.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 race was canceled as part of the City of Long Beach's ban on events with estimated attendance of more than 250.[8] The following year, as a preparatory measure for the pandemic's effects on the schedule, the race was moved from its traditional April date to September 26, and served as the season finale.[9] With the rise of the Delta variant there were concerns from IndyCar and the event promoters that the race would have to be canceled for 2021 or run with an attendance cap, but the promoters and the city of Long Beach were able to work out a compromise on safety measures and rapid testing to allow the event to go forward with full capacity.[10]

The Grand Prix returned to its traditional April date for the 2022 season.

On March 28, 2024, it was announced that former ChampCar owner Gerald Forsythe would buy a 50% stake in the Long Beach Grand Prix from the estate of the late Kevin Kalkhoven.[11]

First wins

[edit]Despite the challenging nature of the course, the Grand Prix of Long Beach has produced the first Indy/Champ Car victories for several drivers. Drivers who won their first career Indy car race at Long Beach include Michael Andretti, Paul Tracy, Juan Pablo Montoya, Mike Conway, Takuma Sato, and Kyle Kirkwood. For Michael Andretti, the Long Beach Grand Prix has the distinction of being his first career Indy car win (1986), and 42nd and final career IndyCar win (2002).

James Hinchcliffe won his first-career Indy Lights race at Long Beach in 2010, then followed it up with an IndyCar Series win at the track in 2017. In 2005, Katherine Legge won the Atlantic Championship support race at Long Beach, her first start in the series. In doing so, she became the first female driver to win a developmental open-wheel race in North America.[12]

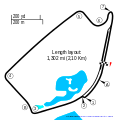

Circuit

[edit]The current race circuit is a 1.968-mile (3.167 km) temporary road course laid out in the city streets surrounding the Long Beach Convention Center. The convention center actually doubled as the pit paddock during the days of Formula One. The circuit also goes primarily over the former location of The Pike historic amusement zone. The track is particularly noted for its last section, a sharp hairpin turn followed by a long, slightly curved front straightaway which runs the length of Shoreline Drive. The circuit is situated on the Long Beach waterfront, and is lined with palm trees (especially along the front straightaway towards the Aquarium of the Pacific), making for a scenic track. Long Beach is classified as an FIA Grade Two circuit.[13]

The circuit has undergone numerous layout changes since the race's inception in 1975. All iterations have featured a signature hairpin turn, main stretch along Shoreline Drive, and back stretch along Seaside Way or Ocean Boulevard. The first grand prix layout measured 2.02 miles, and featured two hairpins, one at each end of the Shoreline Drive straightaway. In its early years, the starting line and the finish line were located on different sides of the course.

In 1982, the hairpin turn and the end of the main stretch (turn 1) was removed, and replaced with a 90-degree right turn, followed by 90-degree left turn. When the race became a CART series event, the layout was changed significantly. The final turn hairpin was moved to the east, closer to the pit entrance. Other slow chicanes and turns were removed. After a minor tweak to the layout in 1987, the track was shortened in 1992 by the removal of the Park Avenue loop. That created a longer Seaside Way back stretch and a faster run to the passing zone.

In 1999, due to new construction in the area, the turn one set of curves was removed, and replaced with the new fountain complex. Turn one now became a 90-degree left turn, leading into a roundabout around a fountain, and a series of three 90-degree turns. A year later, this segment was revised again, to create a longer straightaway leading to Pine Avenue. This course layout remains intact today.

Course layouts

[edit]-

Grand Prix Circuit (1975–1977)

-

Grand Prix Circuit (1978–1981)

-

Grand Prix Circuit (1982)

-

Grand Prix Circuit (1983)

-

Grand Prix Circuit (1992–1998)

-

Grand Prix Circuit (1999)

-

Grand Prix Circuit (2000–present)

-

ePrix Circuit (2015–2016)

Events

[edit]Formula 5000 and Formula One

[edit]The inaugural race was held as part of the Formula 5000 series. From 1976 to 1983 the event was a Formula One race, commonly known as the United States Grand Prix West.

The City of Long Beach and the Grand Prix Association signed a contract in 2014 to hold the Grand Prix as part of the IndyCar Series through 2018, with optional extensions available through 2020.[14] In 2016, the Long Beach City Council issued an RFP, opening up consideration for returning the event to a Formula One race as early as 2019.[15] In August 2017, after a study was completed and after discussions, the switch to Formula One was rejected. The city council voted unanimously to continue the event as part of the IndyCar Series.[16]

2008 Long Beach/Motegi "split weekend"

[edit]

During negotiations which led to the unification of the Champ Car World Series and the IRL IndyCar Series in 2008, a scheduling conflict arose between the IndyCar race held at Twin Ring Motegi (April 19) and the Champ Car race at Long Beach (April 20). Neither party was able to reschedule their event.

A compromise was made to create a unique "split weekend" of races at Motegi and Long Beach. The existing Indy Racing League teams would compete in Japan, while the ex-Champ Car teams raced at Long Beach. Both races paid equal points towards the 2008 IndyCar Series championship. The ex-Champ Car teams utilized the Panoz DP01 machines, the cars that would have been used in 2008 had the unification not taken place. The 2008 Long Beach Grand Prix was billed as the "final Champ Car race."

Drifting

[edit]Beginning in 2005, the event included a demonstration by participants in the Formula D drifting series. Since 2006 Formula D has held the first round of their pro series on Turns 9–11 on the weekend prior to the Grand Prix. In 2013 the Motegi Super Drift Challenge, a drifting competition, was added on the GP weekend, using the same Turn 9–11 course as Formula D. The Motegi Super Drift Challenge is the only event during the GP that runs at night, under floodlights.

North American Touring Car Championship

[edit]Long Beach hosted the opening round of the 1997 North American Touring Car Championship, being won by Neil Crompton in a Honda Accord.

Formula E

[edit]A modified version of the Long Beach Grand Prix track was used during the Long Beach ePrix of the FIA Formula E Championship. The track is 2.1 km (1.3 mi) in length and features seven turns.[17][18] Admission to the first event was free: "the free admission will afford everyone the opportunity to come out and witness this historic and unique event", Jim Michaelian, president of the Grand Prix Assn. of Long Beach, said in a statement.[19][20] The ePrix was held once again in 2016. However, it was not renewed for the third Formula E season in 2017.[21]

Race winners

[edit]| Season | Date | Driver | Team | Chassis | Engine | Tires | Race distance | Race time | Average speed (mph) |

Report | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laps | Miles (km) | ||||||||||

| Formula 5000 | |||||||||||

| 1975 | Sept 28 | Carl A. Haas Racing | Lola T332 | Chevrolet | Goodyear | 50 | 101 (162.543) | 1:10:12 | 86.325 | Report | |

| Formula One | |||||||||||

| 1976 | March 28 | Scuderia Ferrari SpA SEFAC | Ferrari 312T | Ferrari | Goodyear (2) | 80 | 161.6 (260.069) | 1:53:18 | 85.572 | Report | |

| 1977 | April 3 | Team Lotus | Lotus 78 | Ford–Cosworth | Goodyear (3) | 80 | 161.6 (260.069) | 1:51:35 | 87.073 | Report | |

| 1978 | April 2 | Scuderia Ferrari SpA SEFAC (2) | Ferrari 312T3 (2) | Ferrari (2) | Michelin | 80 | 161.6 (260.069) | 1:52:01 | 86.555 | Report | |

| 1979 | April 8 | Scuderia Ferrari SpA SEFAC (3) | Ferrari 312T4 (3) | Ferrari (3) | Michelin (2) | 80 | 161.6 (260.069) | 1:50:25 | 87.812 | Report | |

| 1980 | March 30 | Brabham Racing Team | Brabham BT49 | Ford–Cosworth (2) | Goodyear (4) | 80 | 161.6 (260.069) | 1:50:18 | 87.899 | Report | |

| 1981 | March 15 | Williams Racing Team | Williams FW07 | Ford–Cosworth (3) | Goodyear (5) | 80 | 161.6 (260.069) | 1:50:41 | 87.601 | Report | |

| 1982 | April 4 | McLaren International | McLaren MP4/1 | Ford–Cosworth (4) | Goodyear (6) | 75 | 159.75 (257.092) | 1:58:25 | 80.939 | Report | |

| 1983 | March 27 | McLaren International (2) | McLaren MP4/1 (2) | Ford–Cosworth (5) | Michelin (3) | 75 | 152.55 (245.505) | 1:53:34 | 80.624 | Report | |

| CART/Champ Car World Series | |||||||||||

| 1984 | March 31 | Newman/Haas Racing | Lola (2) | Cosworth (6) | Goodyear (7) | 112 | 187.04 (301.011) | 2:15:23 | 82.898 | Report | |

| 1985 | April 14 | Newman/Haas Racing (2) | Lola (3) | Cosworth (7) | Goodyear (8) | 90 | 150.3 (241.884) | 1:42:50 | 87.694 | Report | |

| 1986 | April 13 | Kraco Racing | March | Cosworth (8) | Goodyear (9) | 95 | 158.65 (255.322) | 1:57:34 | 80.965 | Report | |

| 1987 | April 5 | Newman/Haas Racing (3) | Lola (4) | Chevrolet (2) | Goodyear (10) | 95 | 158.65 (255.322) | 1:51:33 | 85.33 | Report | |

| 1988 | April 17 | Galles Racing | March (2) | Chevrolet (3) | Goodyear (11) | 95 | 158.65 (255.322) | 1:53:47 | 83.655 | Report | |

| 1989 | April 16 | Galles Racing (2) | Lola (5) | Chevrolet (4) | Goodyear (12) | 95 | 158.65 (255.322) | 1:51:19 | 85.503 | Report | |

| 1990 | April 22 | Galles/Kraco Racing (3) | Lola (6) | Chevrolet (5) | Goodyear (13) | 95 | 158.65 (255.322) | 1:53:00 | 84.227 | Report | |

| 1991 | April 14 | Galles/Kraco Racing (4) | Lola (7) | Chevrolet (6) | Goodyear (14) | 95 | 158.65 (255.322) | 1:57:14 | 81.195 | Report | |

| 1992 | April 12 | Galles/Kraco Racing (5) | Galmer | Chevrolet (7) | Goodyear (15) | 105 | 166.53 (268.004) | 1:48:56 | 91.945 | Report | |

| 1993 | April 18 | Team Penske | Penske | Chevrolet (8) | Goodyear (16) | 105 | 166.53 (268.004) | 1:47:36 | 93.089 | Report | |

| 1994 | April 17 | Team Penske (2) | Penske (2) | Ilmor | Goodyear (17) | 105 | 166.53 (268.004) | 1:40:53 | 99.283 | Report | |

| 1995 | April 9 | Team Penske (3) | Penske (3) | Mercedes-Benz | Goodyear (18) | 105 | 166.53 (268.004) | 1:49:32 | 91.422 | Report | |

| 1996 | April 14 | Chip Ganassi Racing | Reynard | Honda | Firestone | 105 | 166.53 (268.004) | 1:44:02 | 96.281 | Report | |

| 1997 | April 13 | Chip Ganassi Racing (2) | Reynard (2) | Honda (2) | Firestone (2) | 105 | 166.53 (268.004) | 1:46:17 | 93.999 | Report | |

| 1998 | April 5 | Chip Ganassi Racing (3) | Reynard (3) | Honda (3) | Firestone (3) | 105 | 166.53 (268.004) | 1:51:29 | 88.946 | Report | |

| 1999 | April 18 | Chip Ganassi Racing (4) | Reynard (4) | Honda (4) | Firestone (4) | 85 | 155.04 (249.512) | 1:45:48 | 87.915 | Report | |

| 2000 | April 16 | Team Green | Reynard (5) | Honda (5) | Firestone (5) | 82 | 161.376 (259.709) | 1:57:11 | 82.626 | Report | |

| 2001 | April 8 | Team Penske (4) | Reynard (6) | Honda (6) | Firestone (6) | 82 | 161.376 (259.709) | 1:52:17 | 86.223 | Report | |

| 2002 | April 14 | Team Green (2) | Reynard (7) | Honda (7) | Bridgestone | 90 | 177.12 (285.047) | 2:02:14 | 86.935 | Report | |

| 2003 | April 13 | Forsythe Racing | Lola (8) | Ford–Cosworth (9) | Bridgestone (2) | 90 | 177.12 (285.047) | 1:56:01 | 91.59 | Report | |

| 2004 | April 18 | Forsythe Racing (2) | Lola (9) | Ford–Cosworth (10) | Bridgestone (3) | 81 | 159.408 (256.542) | 1:44:12 | 91.785 | Report | |

| 2005 | April 10 | Newman/Haas Racing (4) | Lola (10) | Ford–Cosworth (11) | Bridgestone (4) | 81 | 159.408 (256.542) | 1:46:29 | 89.811 | Report | |

| 2006 | April 9 | Newman/Haas Racing (5) | Lola (11) | Ford–Cosworth (12) | Bridgestone (5) | 74 | 145.632 (234.371) | 1:40:07 | 87.268 | Report | |

| 2007 | April 15 | Newman/Haas/Lanigan Racing (6) | Panoz | Cosworth (13) | Bridgestone (6) | 78 | 153.504 (247.04) | 1:40:43 | 91.432 | Report | |

| IndyCar Series | |||||||||||

| 2008* | April 20 | KV Racing Technology | Panoz (2) | Cosworth (14) | Bridgestone (7) | 83 | 163.344 (262.876) | 1:45:25 | 92.964 | Report | |

| 2009 | April 19 | Chip Ganassi Racing (5) | Dallara | Honda (8) | Firestone (7) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:58:47 | 84.491 | Report | |

| 2010 | April 18 | Andretti Autosport | Dallara (2) | Honda (9) | Firestone (8) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:47:13 | 93.619 | Report | |

| 2011 | April 17 | Andretti Autosport (2) | Dallara (3) | Honda (10) | Firestone (9) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:53:11 | 88.676 | Report | |

| 2012 | April 15 | Team Penske (5) | Dallara (4) | Chevrolet (9) | Firestone (10) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:54:02 | 88.021 | Report | |

| 2013 | April 21 | A. J. Foyt Enterprises | Dallara (5) | Honda (11) | Firestone (11) | 80 | 157.44 (253.375) | 1:50:09 | 85.763 | Report | |

| 2014 | April 13 | Ed Carpenter Racing | Dallara (6) | Chevrolet (10) | Firestone (12) | 80 | 157.44 (253.375) | 1:54:42 | 82.362 | Report | |

| 2015 | April 19 | Chip Ganassi Racing (6) | Dallara (7) | Chevrolet (11) | Firestone (13) | 80 | 157.44 (253.375) | 1:37:35 | 96.8 | Report | |

| 2016 | April 17 | Team Penske (6) | Dallara (8) | Chevrolet (12) | Firestone (14) | 80 | 157.44 (253.375) | 1:33:54 | 100.592 | Report | |

| 2017 | April 9 | Schmidt Peterson Motorsports | Dallara (9) | Honda (12) | Firestone (15) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:50:29 | 90.845 | Report | |

| 2018 | April 15 | Andretti Autosport (3) | Dallara (10) | Honda (13) | Firestone (16) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:53:15 | 88.622 | Report | |

| 2019 | April 14 | Andretti Autosport (4) | Dallara (11) | Honda (14) | Firestone (17) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:41:35 | 88.622 | Report | |

| 2020 | Canceled in response to the COVID-19 pandemic | ||||||||||

| 2021 | September 26* | Andretti Autosport with Curb Agajanian (5) | Dallara (12) | Honda (15) | Firestone (18) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:49:10 | 91.935 | Report | |

| 2022 | April 10 | Team Penske (7) | Dallara (13) | Chevrolet (13) | Firestone (19) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:46:48 | 93.977 | Report | |

| 2023 | April 16 | Andretti Autosport (6) | Dallara (14) | Honda (16) | Firestone (20) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:43:17 | 97.171 | Report | |

| 2024 | April 21 | Chip Ganassi Racing (7) | Dallara (15) | Honda (17) | Firestone (21) | 85 | 167.28 (269.211) | 1:43:03 | 98.350 | Report | |

| 2025 | April 13 | Andretti Global (7) | Dallara (16) | Honda (18) | Firestone (22) | 90 | 177.12 (285.05) | 1:45:51 | 100.395 | Report | |

Notes

[edit]- 2008: Race sanctioned by the IndyCar Series; used cars and regulations from the Champ Car World Series and held on same day as Indy Japan 300 due to scheduling conflict as a result of reunification.

- 2021: Race rescheduled to September due to COVID-19 pandemic

Race summaries

[edit]

CART PPG Indy Car World Series

[edit]- 1984: After eight years, the Long Beach Grand Prix changed to a CART series race. The race served as the 1984 season opener. Mario Andretti, who won the 1977 race, won the pole position, took the lead at the start and led all 112 laps en route to a dominating victory. The only other driver to finish the race on the lead lap was Geoff Brabham, who finished second on only seven cylinders. Two-time World Champion Emerson Fittipaldi made his CART debut with a 4th-place finish.[22]

- 1985: Mario Andretti started on the pole position, and led the first 58 laps. Andretti's strategy was to try to complete the race on one pit stop. After building up an over 10-second lead, Andretti pitted on lap 44. In order to conserve fuel, however, he subsequently dialed back his turbocharger boost. Danny Sullivan had pitted on lap 37. With Andretti slowing his pace, Sullivan went on a charge, dicing through traffic and caught up to Andretti. On the back stretch on lap 59, Sullivan took the lead and began pulling out to a 15-second advantage. It was expected that the race would be decided between Sullivan and Andretti, with Sullivan needing one final pit stop, and Andretti gambling on going the distance. The Penske Team was planning a timed pit stop for Sullivan, hoping to fuel the car, and get back out on the track in close proximity to Andretti. On lap 79, Sullivan shockingly ran out of fuel coming out of the hairpin, and he coasted into the pits barely under power. Sullivan lost many seconds, allowing Andretti to re-take the lead. Andretti led the rest of the way and won at Long Beach for the second year in a row, and third time overall. Sullivan ran out of fuel again on the last lap, and wound up third.[23][24]

- 1986: Michael Andretti scored the first win of his CART career, battling Al Unser Jr. to the finish over a frantic final 25 laps. Michael Andretti made his final pit stop on lap 56, while Al Unser Jr. pitted on lap 69. Unser came out of the pits just ahead of Andretti, but on cold tires, had difficulties holding off the challenge. Down the back stretch on lap 70, Andretti got by and re-assumed the lead. Unser stayed in close contact with Andretti, and on lap 80 when Andretti came upon the lapped car of Roberto Moreno, Unser closed dramatically. Andretti tried to lap Moreno at the end of the back stretch (turn 11), but the two cars nearly clipped wheels and Andretti locked up the brakes. Unser dove below both cars and went side by side with Andretti going into turn 12. Andretti barely held off Unser going into the hairpin. The cars battled nearly nose-to-tail to the finish, with Andretti winning the race by 0.380 seconds.[25]

- 1987: Mario Andretti started on the pole position and led all 95 laps, en route to his third CART win at Long Beach, and fourth win overall. Andretti's victory marked the first-ever Indy car win for the Ilmor–Chevy Indy V-8 engine. Mario Andretti's only serious challenge was from Emerson Fittipaldi. The drivers pulled away from the field and dominated the first half. Fittipaldi, however, suffered from a broken wastegate, and eventually dropped out with a burned piston on lap 52. Andretti cruised the rest of the way, lapping the field. For the third year in a row, Bobby Rahal dropped out early after contact with the concrete wall.[26][27]

- 1988: Al Unser Jr. snapped the Andretti family winning streak at Long Beach, winning the race for the first time, in dominating fashion. Unser Jr. started fourth, but at the start, settled into second behind Mario Andretti. Going into the hairpin at the end of the first lap, Unser dove below Andretti and took the lead. On his first pit stop, Unser suffered a cross-threaded lug nut, and dropped to sixth, putting Danny Sullivan into the lead. Unser charged, however, gaining nearly a second per lap, re-taking the lead for good on lap 42. Unser led 72 of the 95 laps, lapping the entire field, and when Sullivan dropped out on lap 82, was all alone to the finish. Bobby Rahal finished second, his best career Long Beach result, driving the Judd AV engine.[28][29]

- 1989: Al Unser Jr. led 72 of the first 74 laps, but late in the race, Unser found himself in a battle with Mario and Michael Andretti. All three drivers made their final pit stops, and after a faster pit stop, Mario Andretti emerged as the leader on lap 78, with Unser second, and Michael now a distant third. Unser was close behind Mario when they approached the lapped car of Tom Sneva. At the exit of turn two, and going into turn three, Unser dove under Mario Andretti for the lead, but punted Mario's right-rear wheel. Andretti was sent spinning out with a flat tire and broken suspension, while Unser broke part of his front wing, and bent his steering. Despite the damage, Unser nursed the crippled car to the finish line, winning by 12.377 seconds over Michael Andretti. The contact was controversial, and after the race, Mario called the move "stupid driving." Unser accepted blame for the contact.[30][31]

- 1990: Al Unser Jr. led 91 of 95 laps, but late in the race, had to hold off the challenge of Penske teammates Emerson Fittipaldi and Danny Sullivan for the victory. On lap 2, Fittipaldi and Sullivan banged wheels, causing Sullivan to spin and collect Michael Andretti. Both Sullivan and Andretti recovered and charged up through the field as the race went progressed. With Unser Jr. holding a 10-second lead, a caution came out on lap 66 which bunched the field and erased Unser's advantage. All of the leaders pitted, and when the green flag came back out on lap 70, Fittipaldi was able to close up behind Unser. Fittipaldi got within two car lengths, but Unser held on for the victory. After the early altercation, Danny Sullivan and Michael Andretti finished 3rd and 4th. It was Al Unser Jr.'s third consecutive win at Long Beach.[32]

- 1991: Al Unser Jr. set an event record and tied a CART series record, by winning the Long Beach Grand Prix for the fourth year in a row. The race, however, is best-remembered for a frightening pit road collision between Michael Andretti and Emerson Fittipaldi. Michael Andretti started on the pole and led the first lap, but Al Unser Jr. took the lead on lap 2. Unser stretched his lead to as large as 16 seconds, while Andretti ran second much of the afternoon. On lap 70, Unser and Andretti made their final pit stops. Unser returned to the track with the lead. While Andretti was exiting the pit lane, Emerson Fittipaldi came out of his pit stall in the path of Andretti. The two cars touched wheels, Andretti's car flew up on its side, then came to rest on top of Fittipaldi's sidepod. The two cars were too damaged to return, but neither driver was injured. After the pit road mishap, Unser cruised to victory, with his Galles/KRACO Racing teammate Bobby Rahal coming home second.[33][34]

- 1992: Going for an unprecedented fifth win in a row at Long Beach, Al Unser Jr. lead 54 laps, and was leading with less than four laps to go. His Galles/KRACO Racing teammate Danny Sullivan was right behind in second, challenging for the lead in the closing laps. Bobby Rahal and Emerson Fittipaldi were also nose-to-tail with the leaders. Going down the back stretch on lap 102, Sullivan dove low to make the pass, but Unser closed the door. The two cars tangled, and Unser was sent spinning out into a tire barrier. Sullivan took the lead, and staved off Rahal and Fittpaldi to the finish line. It was the first ever win for the Galmer chassis, and Sullivan's first Indy car win since 1990. Unser Jr. recovered from the spin, and finished in 4th place.[35][36] The race started out on the first lap with a collision between Mario Andretti and Eddie Cheever, which started a standing feud between the two.

- 1993: Paul Tracy won his first career Indy car race, battling Nigel Mansell most of the afternoon. Tracy led 81 of the 105 laps, but his day was not without incident. While leading the race on lap 25, he clipped wheels with Danny Sullivan, and was forced to pit with a flat tire. Later on lap 61, he had to make an unscheduled pit stop for a blistered tire. Tracy re-assumed the lead on lap 74 after Mansell made his final pit stop, and when Mansell later lost second gear, Tracy cruised to the finish. Bobby Rahal, running 11th at the halfway point, finished 2nd in the RH chassis, owing much to the fact that Mansell, Scott Goodyear, Mario Andretti, Raul Boesel all suffered contact or mechanical problems late in the race.[37][38]

- 1994: Al Unser Jr., who had joined Team Penske during the offseason, won his first race driving for his new team, and his record fifth victory at Long Beach. Penske teammates Paul Tracy, Unser, and Emerson Fittipaldi started 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, respectively, and combined to lead all but two laps. Tracy and Fittipaldi led early, but both eventually dropped out with gearbox failures. Tracy spun four times due to the axle-hopping from the gearbox issues, including spinning out while leading the race on lap 20. Unser led 61 laps, and despite a black flag penalty for violating the pit road speed limit, won the race going away. Nigel Mansell finished second, but had lost considerable time when he and Michael Andretti made contact, resulting in a flat tire.[39][40]

- 1995: Al Unser Jr. started fourth, and charged to the lead by lap 30. Unser dominated most of the rest of the race, and won his sixth Long Beach Grand Prix in the past eight years. Scott Pruett finished second for Patrick Racing, the best finish for Firestone tires since returning to Indy car racing at the beginning of the season. Contenders Bobby Rahal (transmission), Christian Fittipaldi (engine), and Teo Fabi (stop-and-go penalty) all fell from contention in the latter stages of the race.[41][42]

- 1996: Gil de Ferran won the pole position and dominated the race, leading 100 of the first 101 laps. With four laps to go, however, a turbocharger hose came loose, and de Ferrans's car suddenly began to slow. Jimmy Vasser led the final four laps, holding off Parker Johnstone for the victory.[43][44]

- 1997: Gil de Ferran and Alex Zanardi started on the front row, and battled much of the afternoon. Though de Ferran appeared to have the faster machine, Zanardi's Ganassi crew executed faster pit stops, which put Zanardi out in front after each sequences of stops. Charging hard to catch Zanardi, de Ferran clipped the wall on lap 93, and fell out with a damaged suspension.[45][46]

CART FedEx Championship Series

[edit]

- 1998: Alex Zanardi scored an improbable victory, winning at Long Beach for the second year in a row. Zanardi fell a lap down early in the race after a collision resulted in a bent steering arm. The race lead was being contested between Bryan Herta, Gil de Ferran, Dario Franchitti, and Hélio Castroneves. With a race-record seven cautions, Zanardi managed to get back on the lead lap and slowly worked his way up through the field. On lap 72, Zanardi pitted for tires and fuel, while most of the leaders stayed out since they had just pitted on lap 56. In the closing stages, all of the leaders except Zanardi were facing a splash-and-go pit stop for fuel. After the leaders cycled through their stops, Herta and Frachitti emerged 1st-2nd, with Zanardi now in third, and charging hard. With five laps to go, the top three were nose-to-tail, and Zanardi passed for second. Three laps later, he took the lead. Zanardi led only the final two laps to steal the win.[47][48]

- 1999: Rookie Juan Pablo Montoya won his first-career Champ/Indy car race, in his third career start, giving Chip Ganassi Racing the team's fourth consecutive victory at Long Beach, in front of a record crowd of 102,000. Montoya started the race fifth, and one by one, picked off the top three cars to move into second behind race leader Tony Kanaan. On lap 46, due to the track breaking up, Kanaan lost control and slid off the course and into a tire barrier. The crash handed the lead to Montoya, who led the rest of the way to victory.[49][50]

- 2000: Paul Tracy started 17th, but steadily climbed to the front of the field, taking the lead on lap 62 to win at Long Beach for the second time. Tracy benefited from strong pit strategy, swift pit work, and an aggressive charge, and managed to put himself in third on lap 58. On a restart with rookie Takuya Kurosawa leading, Roberto Moreno second, and Tracy third, Moreno suddenly slowed with gearbox trouble. Tracy muscled past Kurosawa four laps later, and held off Hélio Castroneves for the victory.[51][52]

- 2001: Hélio Castroneves started from the pole position and led all 82 lap to victory. Despite leading wire-to-wire, Castroneves did not run away with the race, with Cristiano da Matta and Kenny Bräck in close pursuit most of the day. After Brack dropped out with a broken gearbox on lap 30, the race was a two-man battle between Castroneves and da Matta. Castroneves staved off numerous overtake attempts by da Matta in the second half. The margin of victory was a mere 0.534 seconds, one of the closest finishes in Long Beach history.[53]

- 2002: Michael Andretti won the 2002 Grand Prix of Long Beach, his 42nd and final career Indy/Champ car victory. The win came nearly sixteen years to the day of his first career Indy car win – at the same race – the 1986 Long Beach Grand Prix. Andretti started 15th and gambled by pitting out-of-sequence, as did Max Papis. Andretti assumed the lead on lap 62 when the rest of the leaders cycled through routine green flag pit stops. Andretti and Papis led Jimmy Vasser by over 30 seconds, but both still needed one final pit stop for fuel. A full-course caution came out on lap 63, and both drivers took advantage of the break. Meanwhile, Vasser slowed down to be picked up by the pace car, not realizing he was not the race leader, and actually running third. Vasser slowing down gave Andretti and Papis extra time and allowed them to pit without giving up first and second position. Vasser managed to get by Papis when the green came back out, but Andretti held on for the win.[54][55]

- 2003: Michel Jourdain Jr. looked poised to win his first-career CART series race, but mechanical problems foiled his chances at victory. Jourdain started on the pole, but Paul Tracy took the lead at the start and led the first 26 laps. After pit stops, Jourdain assumed the lead on lap 27, and mostly dominated the race over the next 49 laps. The race came down to Jourdain and Tracy, with both drivers needing one final pit stop in the final ten laps. Tracy pitted with 8 laps to go, and came back out on the track still in second place, ahead of Adrián Fernández. Jourdain pitted one lap later, but as he was leaving the pits, the car failed to pull away. A faulty clutch dropped him out of the race, and handed the victory to Tracy. It was Tracy's third win at Long Beach, and he became the first driver in CART history to sweep the first three races of the season.[56][57]

Champ Car World Series

[edit]

- 2004: Paul Tracy won the 30th Long Beach Grand Prix, his fourth victory in the event, and second in a row. At the start, Tracy utilized the new Push-to-pass button to boldly dive from third to first in the first turn. Tracy ran away with the race, giving up the lead only once during a routine pit stop. On lap 2, three cars (Jimmy Vasser, Alex Sperafico, and Tarso Marques) crashed, bringing out the lone caution of the day.[58][59]

- 2005: Sébastien Bourdais worked his way from fourth starting position to the lead by lap 30. Bourdais pulled out to as much as a 7-second lead, and controlled the race most of the way thereafter. A late caution bunched the field, and second place Paul Tracy was on the optional tires, while Bourdais was on the primary tires. Bourdais got the jump on the restart and went on to win, while Tracy became mired behind a lapped car and finished second.[60][61] The race was held under a cloud of uncertainty, as it was in its final contract year with CART/Champ Car. Rumors were swirling around the paddock that the event might switch to the Indy Racing League for 2006.[12]

- 2006: After rumors of a possible switch to IRL, the race returned as part of the Champ Car series. Sébastien Bourdais won for the second year in a row, starting from the pole and leading 70 of the 74 laps. He finished 14 seconds ahead of second place Justin Wilson.

- 2007: Sébastien Bourdais led 58 of 78 laps, dominating en route to his third consecutive Long Beach victory. Paul Tracy crashed during practice on Saturday and sat out with a back injury. He was replaced by Oriol Servia. Will Power passed Alex Tagliani on the last lap to finish second.[62]

- 2008: The 2008 Long Beach Grand Prix was the first to take place after the open wheel unification, and it was considered the final race of the Champ Car era. After the IndyCar and Champ Car calendars were hastily merged, an irreconcilable scheduling conflict arose between Long Beach and the Indy Japan 300. A compromise was made such that the former Champ Car teams competed at Long Beach, while established IndyCar Series teams competed at Motegi. Both races would pay full points to the IndyCar championship, and while Long Beach technically now fell under the sanctioning umbrella of IndyCar, it was run with Champ Car regulations, and was heralded as the "final" Champ Car race. The contingent of former Champ Car teams produced a twenty-car field, all utilizing the turbocharged Cosworth/Panoz DP01 for the final time. From a standing start (the first such at Long Beach since 1983), Will Power got the jump from fourth position to take the lead into turn one. Power led 81 of the 83 laps, relinquishing the top position only during pit stops.

IndyCar Series

[edit]

- 2009: Will Power took the lead from the pole position and led the first 16 laps. Dario Franchitti and Danica Patrick both pitted early on lap 16, and benefited from a full-course caution. Over the next 30 laps, the lead traded between Tony Kanaan, Marco Andretti, and Dario Franchitti. Pitting early once more, Dario Franchitti and Danica Patrick again benefited. Moments later, Mike Conway spun into the tire barrier in turn 8, bringing out the full course caution again. Most of the leaders pitted under the yellow, while Franchitti stayed out to take the lead. Franchitti pulled away and held the lead to the finish, taking the victory. It was his first IndyCar win since 2007, having spent 2008 racing in NASCAR.

- 2010: Will Power started on the pole position, and led the race early. On lap 17, Power errored, when he inadvertently hit the pit road speed limiter button. Ryan Hunter-Reay and Justin Wilson slipped by and Power dropped to third. On a restart on lap 65, Hunter-Reay led, with Power second, and Wilson third. Hunter-Reay had lapped traffic between him and Power and was able to pull out to a comfortable lead. Power, struggling to get through traffic, was passed by Wilson for second. Wilson was not able to close the gap, and Hunter-Reay drove on to victory.

- 2011: With less than 20 laps to go, Mike Conway charged into third place on a restart. He quickly powered past Dario Franchitti and Will Power to take the lead. Conway pulled out to a six-second advantage, and led the final 14 laps en route to his first Indy car victory.

- 2012: Just days prior to the race, Chevrolet announced that all eleven of their entries would change engines, in violation of IndyCar's mileage requirement rule. As a penalty, all of the Chevrolet entries would incur a 10-position grid penalty after time trials. At the start, Dario Franchitti and rookie Josef Newgarden battled into turn one. Newgarden tried to take the lead on the outside, but the two cars clipped slightly, and Newgarden smacked the tire barrier and crashed out of the race. Franchitti took the lead for the first four laps, but quickly faded with handling problems. The race became a contest between rookie Simon Pagenaud and Will Power, with Takuma Sato also strong all afternoon. Power made his final pit stop on lap 64, and attempted to stretch his fuel over the final 21 laps. Pagenaud pitted on lap 70, and seemingly had plenty of fuel to charge to the finish. As Power held the lead, Pagenaud dramatically charged to catch Power, gaining 1–2 seconds per lap. The cars were nose-to-tail in the hairpin as they approached the white flag. Power held off on the final lap to win by 0.8 seconds. Despite the grid penalties, Chevrolet-powered cars swept eight of the top ten finishing positions.

- 2013: Takuma Sato led 50 of 80 laps, and won his first career IndyCar race. Sato effectively took control of the race on lap 23, when he passed Ryan Hunter-Reay for second place in turn 1. After the leaders cycled through pit stops, Sato assumed the lead on lap 31, and did not relinquish the top spot for the remainder of the race. Sato's win was the first for A. J. Foyt Enterprises since 2002.

- 2014: On lap 56, a controversial crash took out six cars, including the drivers running 1st–2nd–3rd. During a sequence of green flag pit stops, Josef Newgarden inherited the lead. Ryan Hunter-Reay, James Hinchcliffe, and Will Power were running nose-to-tail in 2nd–3rd–4th. Newgarden completed his pit stop, and came out on the track just ahead of Hunter-Reay, momentarily holding on to the lead. Going into turn 4, Hunter-Reay attempted a risky pass for the lead, and he made contact with Newgarden, sending both cars into the wall. Hinchcliffe was collected, as was three other cars in the huge melee that nearly blocked the track. Late in the race, Scott Dixon led, followed by Mike Conway and Power close behind. Dixon ran out of fuel, and had to pit with two laps to go. Conway held off Power and Carlos Muñoz to win for the second time at Long Beach.

- 2015: During the first sequence of green flag pit stops on lap 29, leader Hélio Castroneves was briefly held in his pit box to avoid collision with Tony Kanaan, who was entering the stall just ahead. The delay cost Castroneves valuable track position, and allowed Scott Dixon to take over the lead. During the second round of pit stops on lap 55, Dixon was narrowly able to hold the lead, and cruised to victory, his first career win at Long Beach. With Dixon comfortably out in front, and Castroneves in second, the closing laps focused on a furious four-car battle for third place, led by Juan Pablo Montoya and Simon Pagenaud. Fifth place went to Tony Kanaan.

- 2016: Hélio Castroneves led 49 of the first 51 laps. During the second round of stops, Scott Dixon was able to pass Castroneves with quick pit work. However, Simon Pagenaud's pit stop was even faster, and he emerged with the lead of the race. Controversy followed, as Pagenaud placed two tires over the blend line at the exit of pit lane while trying to beat Dixon to turn one. IndyCar officials let Pagenaud off with a warning for the incident, despite protests from Chip Ganassi Racing. Pagenaud held off Dixon by 0.3032 seconds, the closest finish in Long Beach history.

- 2017: James Hinchcliffe won for the first time since his serious crash during practice at the 2015 Indianapolis 500. In the late stages of the race, Andretti Autosport teammates Alexander Rossi, Takuma Sato, and Ryan Hunter-Reay all dropped out with mechanical problems, leaving Hinchcliffe to battle Sébastien Bourdais and Josef Newgarden to the finish. On a restart with three laps to go, Hinchcliffe got the jump and held on for the victory.

- 2021: The new Roger Penske-led IndyCar Series returned to Long Beach in 2021 after the 2020 event was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The race was moved from the traditional early season slot in April to the season finale on September 26 due to the ongoing pandemic, effectively ending the season with a three race west coast swing. The race was a championship-deciding showdown between three drivers; Alex Palou of Chip Ganassi Racing, Pato O'Ward of Arrow McLaren SP, and Josef Newgarden of Team Penske. Palou held a 35-point advantage over his rivals, meaning he only had to finish no worse than 11th to win the championship. O'Ward and Newgarden both had to qualify on the pole to earn the awarded bonus point and win the race to put themselves in a position to win the championship. If he met those prerequisites, O'Ward needed Palou to finish no better than thirteenth to win the championship. Newgarden needed to meet those prerequisites and for Palou to finish no better than twentieth and O'Ward to finish no better than third to win the championship. Qualifying for the race was highly controversial due to a yellow flag caused by Will Power that prevented both Palou and O'Ward from advancing into the Firestone Fast Six while Newgarden advanced. Newgarden won his season-leading fourth pole position and first ever at Long Beach while Palou qualified tenth and O'Ward eighth. Further controversy erupted in a first lap pile up when Ed Jones ran into the back of O'Ward and broke a driveshaft on O'Ward's car. The incident knocked O'Ward out of the race and the championship battle. Meanwhile Colton Herta mounted a furious charge to the front of the field from fourteenth and overtook Scott Dixon and Newgarden for the lead on lap 31 en route to his third win of the season. Palou drove a conservative race into fourth place to secure his first IndyCar championship. Newgarden and Dixon finished second and third respectively.[63]

- 2022: Long Beach returned to its traditional early season slot for 2022. Colton Herta took pole position and led the early stint of the race before Josef Newgarden and Alex Palou overcut Herta in the first series of pitstops. Herta would attempt to attack both Newgarden and Palou before he crashed into the walls near Turn 9. Newgarden then overcut Palou in the next pitstop sequence for the race lead. Herta's teammate and former Haas F1 driver Romain Grosjean managed to pass Palou after the last round of pitstops and began to cut into Newgarden's lead late in the race by virtue of running on a brand new set of alternate tires while Newgarden ran on used primary tires. Newgarden and Grosjean heavily leaned into their push to pass quota, with both using all of their extra horsepower heading into the final ten laps. A late yellow caused by Jimmie Johnson and David Malukas bunched the field together before Newgarden and Grosjean pulled away again for what appeared to be a near photo finish. The race ultimately ended under caution when Takuma Sato made contact with a wall on the last lap. Newgarden claimed his second victory in a row, helping Team Penske win the first three events of the season. Grosjean meanwhile finished second to earn his first podium with Andretti Autosport. Alex Palou rounded out the podium.[64]

- 2023: Kyle Kirkwood qualified on pole, his first IndyCar pole position. Kirkwood led the initial sequence of the race before a yellow caused by contact between Pato O'Ward and Scott Dixon on lap 20 shuffled the field, with most of the field pitting under caution. 2022 race winner Josef Newgarden took the lead from Kirkwood on Lap 26 and held it through the middle stint of the race. Newgarden and Romain Grosjean made their last pitstop with 32 laps to go, while Kirkwood and strategist Bryan Herta elected to remain out for one lap longer. The overcut sequence worked, Kirkwood overtook both Newgarden and Grosjean for the race lead, and held onto it for his first IndyCar win. Newgarden faded from the front of the field due to fuel saving, leading Romain Grosjean and reigning Indianapolis 500 winner Marcus Ericsson to finish second and third respectively.

- 2024: Felix Rosenqvist qualified on pole, earning the first pole position ever for Meyer Shank Racing in IndyCar. Rosenqvist lost the lead on the opening lap early to Will Power. The first yellow of the day came on Lap 15 by Christian Rasmussen, and Power was forced to pit and relinquish the lead to Josef Newgarden. Newgarden later surrendered the lead under a green flag pit stop around lap 31 to Colton Herta. Herta lost the lead at lap 62 to Scott Dixon, who was running a tight fuel saving strategy. Newgarden heavily pursued Dixon in the closing laps, but was rear ended by Colton Herta and stalled with nine laps to go. This let Herta and Alex Palou by. Herta pursued Dixon heavily, but Dixon conserved enough fuel to use up his significant push to pass advantage to build a gap between himself and Herta to take his second win at Long Beach. Herta finished second and Alex Palou rounded out the podium.

- 2025: The 2025 iteration of the Long Beach Grand Prix was extended from 85 laps to 90 laps. Kyle Kirkwood qualified on pole and led the entire race. Alex Palou attempted numerous undercuts to attempt to gain the advantage on Kirkwood but the Andretti driver held strong. Uniquely for Long Beach, the race ran entirely under a green flag. Palou settled for second while Christian Lundgaard rounded out the podium in third.

Other race winners

[edit]Road to Indy

[edit]IMSA GTO/GTU

[edit]| Year | GTO | GTU | Report |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Mercury Cougar |

Mazda MX-6 |

Report |

| 1991 | Nissan 300ZX |

Dodge Daytona |

Report |

Rolex Sports Car Series

[edit]| Rolex Sports Car Series | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Drivers | Car | Report | |||

| 2006 | Riley Mk XX–Lexus | Report | ||||

American Le Mans Series

[edit]| Year | LMP1 | LMP2 | GT1 | GT2 | Report | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Audi R10 TDI |

Porsche RS Spyder |

Chevrolet Corvette C6.R |

Ferrari F430 GT2 |

Report | |

| 2008 | Audi R10 TDI |

Acura ARX-01b |

Chevrolet Corvette C6.R |

Ferrari F430 GT2 |

Report | |

| 2009 | Acura ARX-02a |

Acura ARX-01b |

Chevrolet Corvette C6.R |

Porsche 911 GT3-RSR |

Report | |

| LMP | LMPC | GT | GTC | |||

| 2010 | HPD ARX-01c |

Oreca FLM09/Chevrolet |

Porsche 911 GT3-RSR |

Porsche 997 GT3 Cup |

Report | |

| LMP1 | LMP2 | LMPC | GT | GTC | ||

| 2011 | Lola-Aston Martin B09/60 |

HPD ARX-03b |

Oreca FLM09/Chevrolet |

BMW M3 GT2 |

Porsche 997 GT3 Cup |

Report |

| 2012 | HPD ARX-03a |

HPD ARX-03b |

Oreca FLM09/Chevrolet |

Chevrolet Corvette C6.R |

Porsche 997 GT3 Cup |

Report |

| 2013 | HPD ARX-03a |

HPD ARX-03b |

Oreca FLM09/Chevrolet |

BMW Z4 GTE |

Porsche 997 GT3 Cup |

Report |

IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship

[edit]| Year | Prototype | Prototype Challenge | GT Le Mans | GT Daytona | Report | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Riley DP/Ford |

did not participate | Chevrolet Corvette C7.R |

did not participate | Report | ||||||

| 2015 | Corvette DP/Chevrolet |

did not participate | BMW Z4 GTE |

did not participate | Report | ||||||

| 2016 | Corvette DP/Chevrolet |

Oreca FLM09/Chevrolet |

Porsche 911 RSR |

did not participate | Report | ||||||

| 2017 | Cadillac DPi-V.R |

did not participate | Chevrolet Corvette C7.R |

Mercedes-AMG GT3 |

Report[65] | ||||||

| Year | Prototype | GT Le Mans | GT Daytona | Report | |||||||

| 2018 | Cadillac DPi-V.R |

Chevrolet Corvette C7.R |

did not participate | Report[66] | |||||||

| Year | Daytona Prototype international | GT Le Mans | GT Daytona | Report | |||||||

| 2019 | Cadillac DPi-V.R |

Porsche 911 RSR |

did not participate | Report[67] | |||||||

| 2020 | Canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic | ||||||||||

| 2021 | Cadillac DPi-V.R |

Chevrolet Corvette C8.R |

Lamborghini Huracán GT3 Evo |

Report[68] | |||||||

| Year | Daytona Prototype international | GT Daytona Pro | GT Daytona | Report | |||||||

| 2022 | Cadillac DPi-V.R |

Aston Martin Vantage AMR GT3 |

BMW M4 GT3 |

Report | |||||||

| Year | Grand Touring Prototype | GT Daytona Pro | GT Daytona | Report | |||||||

| 2023 | Porsche 963 |

Lexus RC F GT3 |

BMW M4 GT3 |

Report | |||||||

| 2024 | Cadillac V-Series.R |

did not participate | Lexus RC F GT3 |

Report | |||||||

- Overall winners in bold

Stadium Super Trucks

[edit]| Year | Date | Driver | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | April 21 | [69] | |

| 2014 | April 13 | [70] | |

| 2015 | April 19 | [71] | |

| 2016 | April 16 | [72] | |

| April 17 | |||

| 2017 | April 8 | [73] | |

| April 9 | [74] | ||

| 2018 | April 14 | [75] | |

| April 15 | [76] | ||

| 2019 | April 13 | [77] | |

| April 14 | [78] | ||

| 2020 | Canceled due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic | ||

| 2021 | September 25 | [79] | |

| September 26 | [80] | ||

| 2022 | April 9 | [81] | |

| April 10 | [82] | ||

| 2023 | April 15 | [83] | |

| April 16 | [84] | ||

| 2024 | April 20 | [85] | |

| April 21 | [86] | ||

| 2025 | April 12 | [87] | |

| April 13 | [88] | ||

Lap records

[edit]As of April 2025, the fastest official race lap records at the Grand Prix of Long Beach are listed as:

| Category | Time | Driver | Vehicle | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Prix Circuit: 3.167 km (2000–present)[89] | ||||

| IndyCar | 1:07.2359 | Álex Palou | Dallara DW12 | 2022 Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| Champ Car | 1:07.931 | Sébastien Bourdais | Lola B02/00 | 2006 Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| CART | 1:08.981 | Bruno Junqueira | Lola B02/00 | 2002 Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| DPi | 1:10.317[90] | Sébastien Bourdais | Cadillac DPi-V.R | 2022 Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| LMDh | 1:11.503[91] | Connor De Phillippi | BMW M Hybrid V8 | 2023 Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| LMP2 | 1:12.383[92] | Patrick Long | Porsche RS Spyder EVO | 2008 American Le Mans Series at Long Beach |

| LMP1 | 1:12.599[92] | Marco Werner | Audi R10 TDI | 2008 American Le Mans Series at Long Beach |

| Indy Lights | 1:12.9009[93] | Félix Serrallés | Dallara IL-15 | 2015 Long Beach 100 |

| LMH | 1:14.479[94] | Ross Gunn | Aston Martin Valkyrie AMR-LMH | 2025 Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| DP | 1:15.279[95] | Dane Cameron | Corvette Daytona Prototype | 2016 BUBBA Burger Sports Car Grand Prix |

| Formula Atlantic | 1:16.058[96] | Richard Philippe | Swift 016.a | 2006 Long Beach Formula Atlantic round |

| LM GTE | 1:17.215[97] | Oliver Gavin | Chevrolet Corvette C7.R | 2019 BUBBA Burger Sports Car Grand Prix |

| LMPC | 1:17.244[95] | Kyle Marcelli | Oreca FLM09 | 2016 BUBBA Burger Sports Car Grand Prix |

| GT1 (GTS) | 1:17.415[92] | Oliver Gavin | Chevrolet Corvette C6.R | 2008 American Le Mans Series at Long Beach |

| GT3 | 1:18.617[90] | Raffaele Marciello | Mercedes-AMG GT3 Evo | 2022 Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| GT | 1:19.511[98] | Oliver Gavin | Chevrolet Corvette C6.R | 2013 American Le Mans Series at Long Beach |

| Global Time Attack | 1:19.571[99] | Feras Qartoumy | Corvette Z06 | 2021 Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| Porsche Carrera Cup | 1:19.660[100] | Kay van Berlo | Porsche 911 (992) GT3 Cup | 2022 Long Beach Porsche Carrera Cup North America round |

| SRO GT2 | 1:21.216[101] | Aaron Farhadi | Lamborghini Huracán Super Trofeo GT2 | 2024 Long Beach GT America round |

| Trans-Am | 1:22.030[102] | Paul Gentilozzi | Jaguar XKR | 2003 Long Beach Trans-Am round |

| IMSA GTO | 1:24.448[103] | Craig Bennett | Nissan 300ZX Turbo | 2019 Historic IMSA GTO/Trans-Am Invitational |

| GT4 | 1:25.773[101] | Isaac Sherman | Porsche 718 Cayman GT4 RS Clubsport | 2024 Long Beach GT America round |

| Stadium Super Trucks | 1:44.939[103] | Matthew Brabham | Stadium Super Truck | 2019 Long Beach SST round |

| Formula E Circuit: 2.131 km (2015–2016)[89] | ||||

| Formula E | 0:57.938 | Sébastien Buemi | Renault Z.E 15 | 2016 Long Beach ePrix |

| GP Circuit: 2.935 km (1999)[89][104] | ||||

| CART | 1:02.779[105] | Juan Pablo Montoya | Reynard 99I | 1999 Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| Indy Lights | 1:08.623[106] | Felipe Giaffone | Lola T97/20 | 1999 Long Beach Indy Lights round |

| Grand Prix Circuit: 2.552 km (1992–1998)[89][104] | ||||

| CART | 0:51.333[107] | Bobby Rahal | Reynard 98I | 1998 Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| Indy Lights | 0:57.190[108] | Cristiano da Matta | Lola T97/20 | 1997 Long Beach Indy Lights round |

| Formula Atlantic | 1:00.249[109] | Jacques Villeneuve | Ralt RT40 | 1993 Long Beach Formula Atlantic round |

| Trans-Am | 1:00.775[110] | Tommy Kendall | Ford Mustang Trans-Am | 1996 Long Beach Trans-Am round |

| Super Touring | 1:06.731[111] | Neil Crompton | Honda Accord | 1997 Long Beach NATCC round |

| IMSA Supercar | 1:10.248[112] | Randy Pobst | BMW M5 | 1995 Long Beach IMSA Supercar round |

| Grand Prix Circuit: 2.687 km (1984–1991)[89][104] | ||||

| CART | 1:08.5563[113] | Mario Andretti | Lola T900 | 1985 Long Beach Grand Prix |

| Formula Atlantic | 1:13.482[114] | Jimmy Vasser | Swift DB4 | 1991 Long Beach Formula Atlantic round |

| Formula Super Vee | 1:14.083[115] | Steve Bren | Ralt RT5 | 1986 Long Beach SCCA Formula Super Vee round |

| IMSA GTO | 1:15.172[116] | Pete Halsmer | Mazda RX-7 | 1991 IMSA Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| Trans-Am | 1:17.772[117] | Scott Pruett | Merkur XR4Ti | 1988 Long Beach Trans-Am round |

| IMSA GTU | 1:20.478[118] | Stu Hayner | Dodge Daytona | 1990 IMSA Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| IMSA AAC | 1:23.020[116] | J. D. Smith | Chevrolet Camaro | 1991 IMSA Grand Prix of Long Beach |

| Grand Prix Circuit: 3.275 km (1983)[89] | ||||

| Formula One | 1:28.330 | Niki Lauda | McLaren MP4/1C | 1983 United States Grand Prix West |

| Grand Prix Circuit: 3.428 km (1982)[89] | ||||

| Formula One | 1:30.831 | Niki Lauda | McLaren MP4B | 1982 United States Grand Prix West |

| Formula Atlantic | 1:37.621[119] | Geoff Brabham | Ralt RT4 | 1982 Long Beach Formula Atlantic round |

| Grand Prix Circuit: 3.251 km (1975–1981)[89] | ||||

| Formula One | 1:19.830 | Nelson Piquet | Brabham BT49 | 1980 United States Grand Prix West |

| Formula 5000 | 1:19.905 | Tony Brise | Lola T332 | 1975 Long Beach Grand Prix |

| Formula Atlantic | 1:27.232[120] | Geoff Brabham | Ralt RT4 | 1981 Long Beach Formula Atlantic round |

Gallery

[edit]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Morales, Robert (February 27, 2008). "Champ Car finale to roar into L.B." The Long Beach Press-Telegram. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ^ Steven Cole Smith (2007-11-06). "Champ Car schedule "stable" for 2008". www.autoweek.com. Archived from the original on 2007-11-10. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ Peltz, James F. (April 7, 2019). "Jim Michaelian steers the Long Beach Grand Prix with a steady hand". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- ^ "Toyota ends 44-year title sponsorship of Long Beach GP". RACER. 2018-08-16. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ^ a b c Miller, Robin (April 18, 1994). "Pook's innovative work made Long Beach a top road course (Part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 11. Retrieved April 9, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Miller, Robin (April 18, 1994). "Pook's innovative work made Long Beach a top road course (Part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 12. Retrieved April 9, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kightlinger, Cathy (April 9, 2017). "Celebrity sightings add glitter to popular Long Beach race". IndyCar.com. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ Glendenning, Mark (March 12, 2020). "Long Beach GP cancelled due to city-wide coronavirus measures". Racer. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Nathan (December 17, 2020). "IndyCar's Long Beach Grand Prix shifts to September as new season finale due to pandemic". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Journalist, Community (22 June 2021). "Start your engines: Long Beach Acura Grand Prix confirms September return with full crowds". ABC7. ABC. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Marshall Pruett (March 28, 2024). "Forsythe to buy remaining Long Beach stake; commits event to IndyCar". RACER. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Ballard, Steve (April 11, 2005). "Race will choose between groups". The Indianapolis Star. p. 29. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "List of FIA licensed circuits" (Press release). Federation Internationale de l'Automobile. December 14, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Stewart, Joshua (April 22, 2014). "Grand Prix will stay in Long Beach until 2018". Long Beach Register. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ "Connecting the dots: Formula 1 and Long Beach could be a match for 2019". AutoWeek. March 7, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Saltzgaver, Harry (August 9, 2017). "SO MOVED: City Council Meeting Aug. 8, 2017". The Grunion. Archived from the original on March 17, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ^ "Circuit Guide | Long Beach, USA – Round 7 | FIA Formula E". FIA Formula E. Archived from the original on 2014-09-06. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ^ "Formula E to race on streets of Long Beach in 2015". FIA Formula E. 2014-04-22. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ^ "Formula E electric-car race in Long Beach to have free admission". LA Times. 2014-07-23. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ^ "Environmentally friendly auto racing series Formula E coming to Long Beach". FIA Formula E. 2014-05-22. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ^ "Formula E will not return to Long Beach in 2017". Long Beach Press Telegram. 2016-07-02. Retrieved 2016-07-30.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 2, 1984). "Mario posts wire-to-wire LBGP win". The Indianapolis Star. p. 18. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 15, 1985). "Andretti outfoxes field for Long Beach win (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 17. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 15, 1985). "Andretti outfoxes field for Long Beach win (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 18. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 14, 1986). "Michael Andretti races to Long Beach victory". The Indianapolis Star. p. 21. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 6, 1987). "Mario victorious at Long Beach (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 17. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 6, 1987). "Mario victorious at Long Beach (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 18. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 18, 1988). "Little Al coasts to Long Beach win (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 17. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 18, 1988). "Little Al coasts to Long Beach win (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 17. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Shaffer, Rick (April 17, 1989). "Long Beach a rough win for Al Jr. (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 17. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Shaffer, Rick (April 17, 1989). "Long Beach a rough win for Al Jr. (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 20. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Shaffer, Rick (April 23, 1990). "Unser Jr. wins at Long Beach". The Indianapolis Star. p. 21. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harris, Mike (April 15, 1991). "Unser jr. cruises to victory (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 29. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harris, Mike (April 15, 1991). "Unser jr. cruises to victory (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 31. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 13, 1992). "Sullivan bumps into victory at Long Beach (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 36. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 13, 1992). "Sullivan bumps into victory at Long Beach (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 38. Retrieved April 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 19, 1993). "Tracy Triumphs at Long Beach (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 9. Retrieved April 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 19, 1993). "Tracy Triumphs at Long Beach (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 13. Retrieved April 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 18, 1994). "Unser wins Toyota GO again despite changes (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 11. Retrieved April 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 18, 1994). "Unser wins Toyota GO again despite changes (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 15. Retrieved April 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 10, 1995). "Unser posts another seaside win (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 15. Retrieved April 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 10, 1995). "Unser posts another seaside win (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 17. Retrieved April 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 15, 1996). "Vasser rides good fortune to third victory (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 23. Retrieved April 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 15, 1996). "Vasser rides good fortune to third victory (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 24. Retrieved April 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 14, 1997). "High-octane work by crew fuels Zanardi (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 15. Retrieved April 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 14, 1997). "High-octane work by crew fuels Zanardi (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 19. Retrieved April 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 6, 1998). "Zanardi steals another unlikely win (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 13. Retrieved April 21, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 6, 1998). "Zanardi steals another unlikely win (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 15. Retrieved April 21, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 19, 1999). "Montoya upholds his team's tradition (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 29. Retrieved April 21, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 19, 1999). "Montoya upholds his team's tradition (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 31. Retrieved April 21, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 17, 2000). "Tracy keeps faith, rallies to wild win (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 11. Retrieved April 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Robin (April 17, 2000). "Tracy keeps faith, rallies to wild win (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 15. Retrieved April 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harris, Mike (April 9, 2001). "Castroneves gives fans a show". The Indianapolis Star. p. 30. Retrieved April 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ballard, Steve (April 15, 2002). "Andretti gambled and wins at Long Beach (part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 23. Retrieved April 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ballard, Steve (April 15, 2002). "Andretti gambled and wins at Long Beach (part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 30. Retrieved April 25, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ballard, Steve (April 14, 2003). "Tracy writes CART history in 3-for-3 start (Part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 25. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ballard, Steve (April 14, 2003). "Tracy writes CART history in 3-for-3 start (Part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 32. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ballard, Steve (April 19, 2004). "Tracy wins with race to 1st turn (Part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 25. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ballard, Steve (April 19, 2004). "Tracy wins with race to 1st turn (Part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 32. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ballard, Steve (April 11, 2005). "Bourdais drives to victory, asks for shot to repeat (Part 1)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 23. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ballard, Steve (April 11, 2005). "Bourdais drives to victory, asks for shot to repeat (Part 2)". The Indianapolis Star. p. 29. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bourdais returns to dominating form at Long Beach". The Indianapolis Star. April 16, 2007. p. D3. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ryan, Nate (27 September 2021). "IndyCar results and points standings after Long Beach". NBC Sports. NBC Universal. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Ryan, Nate (10 April 2022). "Josef Newgarden scores first victory at Long Beach, holding off Romain Grosjean". NBC Sports. NBC Universal. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "2017 BUBBA burger Sports Car Grand Prix at Long Beach" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "Official Race Results" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association. 2018-04-17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-09. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- ^ "Official Race Results" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association. 2019-04-16. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ^ "Official Race Results" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association. 2021-09-25. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ^ "Lofton Soars To Long Beach Victory". Speed Sport. April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ "Motorsports legends Robby Gordon, Bryan Herta to be honored today in Long Beach". Press-Telegram. April 16, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ "E.J. Viso Wins the SST Grand Prix of Long Beach". Race-Dezert. April 20, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ "Sheldon Creed Sweeps Stadium SUPER Trucks Weekend at the Grand Prix of Long Beach". Stadium Super Trucks. April 19, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ "Matt Brabham Wins Race 1 At Long Beach". Stadium Super Trucks. April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ Nguyen, Justin (April 10, 2017). "SST: Long Beach Race #2 Recap". Overtake Motorsport. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ Dottore, Damian (April 15, 2018). "Joao Barbosa's fuel-saving tactic leads to IMSA Sports Car Grand Prix victory". Press-Telegram. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ "Matt Brabham and DeVilbiss Grab Victory at GP of Long Beach". Shortcourse Racer. April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- ^ Dottore, Damian (April 13, 2019). "Grand Prix notes: Driving for a big-time owner brings share of challenges". Press-Telegram. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ Coch, Mat; Herrero, Dan (April 15, 2019). "WORLD WRAP: Aussie James Allen wins ELMS opener". Speedcafe. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ Morales, Robert (September 25, 2021). "Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach: Jerett Brooks wins first of two Super Stadium Trucks races". Press-Telegram. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Nguyen, Justin (September 27, 2021). "Robby Gordon becomes SST Long Beach all-time winner with Race 2 triumph". The Checkered Flag. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Henderson, Martin (April 9, 2022). "Local product Colton Herta wins pole position for Grand Prix of Long Beach". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ Dottore, Damian (April 10, 2022). "Max Gordon following, closely, in father's racing footsteps". Press-Telegram. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ Pope, Dennis (April 15, 2023). "Grand Prix of Long Beach: Jaminet avoids the other's mistakes to win IMSA SportsCar race". Press-Telegram. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Dottore, Damian (April 16, 2023). "Grand Prix of Long Beach: Patrick Long wins Historic Formula One Challenge". Press-Telegram. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Nguyen, Justin (2024-04-21). "Max Gordon leads another Gordon 1–2 in SST Long Beach Race 1". thecheckeredflag.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ Nguyen, Justin (2024-04-22). "SST Long Beach Race 2 cut short by fence-ripping crash". thecheckeredflag.co.uk/. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ Haddock, Tim (April 12, 2025). "Grand Prix of Long Beach: Justin Rothberg wins GT America race under caution". Press-Telegram. Retrieved May 14, 2025.

- ^ Garcia, Jordi; Ramirez, Marvin (May 9, 2025). "Grand Prix in Long Beach: 50 Years at full speed". The Corsair. Retrieved May 14, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Long Beach - RacingCircuits.info". Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ a b "2022 IMSA Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach - Race Official Results (1 Hours 40 Minutes)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). 12 April 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "2023 Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach - Race Official Results (1 Hours 40 Minutes)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). 19 April 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ a b c "2008 Tequila Patrón American Le Mans Series at Long Beach - ALMS Provisional Race Report" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). 19 April 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "2015 Long Beach Indy Lights". Motor Sport Magazine. 19 April 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ "2025 Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach - Race Results by Driver Fastest Lap" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). 12 April 2025. Retrieved 27 April 2025.

- ^ a b "Long Beach 100 Minutes 2016". 16 April 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ "2006 Formula Atlantic Long Beach". 9 April 2006. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "2019 BUBBA Burger Sports Car Grand Prix - Race Official Results (1 Hours 40 Minutes)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). 16 April 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ "2013 American Le Mans Series Long Beach". 20 April 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "2021 Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach Global Time Attack Race Results". 27 September 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "2022 Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach - Porsche Carrera Cup North America - Race 1 Official Results (40 Minutes)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). 12 April 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Long Beach Grand Prix - Apr. 19 - 21, 2024 / Long Beach, CA - GT America powered by AWS - Race 2 Provisional Results" (PDF). 21 April 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ "Trans-Am Series 2003 :: Race 2 results". 13 April 2003. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Stadium Super Trucks in Long Beach - Long Beach Grand Prix - SST Race 1" (PDF). 13 April 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "Long Beach - Motor Sport Magazine". Motor Sport Magazine. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "1999 Long Beach Grand Prix". Motor Sport Magazine. 18 April 1999. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "1999 Long Beach Indy Lights". Motor Sport Magazine. 18 April 1999. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "1998 Long Beach Grand Prix". Motor Sport Magazine. 5 April 1998. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "1997 Long Beach Indy Lights". Motor Sport Magazine. 13 April 1997. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "1993 Formula Atlantic Long Beach". 17 April 1993. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ "1996 Trans-Am Long Beach". 14 April 1996. Retrieved 5 March 2025.

- ^ "NATCC 1997 » Long Beach Street Circuit Round 2 Results". 13 April 1997. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "IMSA Supercar Long Beach 1995". 9 April 1995. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "1985 Long Beach Grand Prix". Motor Sport Magazine. 14 April 1985. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "1991 Toyota Atlantic Long Beach". 14 April 1991. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ "Super Vee Race : Bren Uses Traffic, Beats Groff to Wire - Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times. 13 April 1986. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Long Beach 1 Hour IMSA GT 1991". 14 April 1991. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "1988 Trans-Am Long Beach". 16 April 1988. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ "Long Beach 1 Hour IMSA GT 1990". 22 April 1990. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ "Long Beach Toyota Long Beach Grand-Prix, April 3 Avril 1982". 3 April 1982. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "Long Beach, March 14 Mars 1981 Toyota Grand-Prix of Long Beach". 14 March 1981. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Morris, Gordon (December 17, 2013). "More Than 40 Years Ago, The 'Roar On The Shore' Was Born". Long Beach Business Journal. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- The magic of Long Beach Archived 2014-04-08 at the Wayback Machine – Racer, David Malsher, 7 April 2014

- Long Beach a success story – ESPN, John Oreovicz, 9 April 2014

External links

[edit]

| Preceded by The Thermal Club IndyCar Grand Prix |

IndyCar Series Grand Prix of Long Beach |

Succeeded by Indy Grand Prix of Alabama |

Grand Prix of Long Beach

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Formula 5000 Era