Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

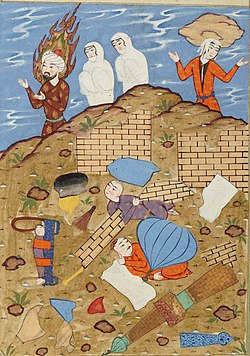

Lot (biblical person)

View on Wikipedia

Lot (/lɒt/; Hebrew: לוֹט Lōṭ, lit. "veil" or "covering";[1] Greek: Λώτ Lṓt; Arabic: لُوط Lūṭ; Syriac: ܠܘܛ Lōṭ) was a man mentioned in the biblical Book of Genesis, chapters 11–14 and 19. Notable events in his life recorded in Genesis include his journey with his uncle Abraham; his flight from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, during which his wife became a pillar of salt.[2] He is regarded as the parental ancestor of Ammonites and Moabites, the enemies of Israelites.

Key Information

Biblical account

[edit]According to the Hebrew Bible, Lot was born to Haran, who died in Ur of the Chaldees. Terah, Lot's grandfather, took Abram (later called Abraham), Lot, and Sarai (later called Sarah) to go into Canaan. They settled at the site called Haran, where Terah died.[3]

As a part of the covenant of the pieces, God told Abram to leave his country and his kindred. Abram's nephew Lot joined him on his journey and they went into the land of Canaan, settling in the hills of Bethel.[4]

Due to famine, Abram and Lot journeyed into Egypt, but Abram pretended that his wife Sarai was his sister. Hearing of her beauty, the Pharaoh took Sarai for his own, for which God afflicted him with great plagues. When the Pharaoh confronted Abram, Abram admitted that Sarai had been his wife all along, and so the Pharaoh forced them out of Egypt.[5]

The plain of Jordan

[edit]When Abram and Lot returned to the hills of Bethel with their many livestock, their respective herdsmen began to bicker. Abram suggested they part ways and let Lot decide where he would like to settle. Lot saw that the plains of the Jordan were well watered "like the gardens of the Lord, like the land of Egypt," and so settled among the cities of the plain, going as far as Sodom. Likewise, Abram went to dwell in Hebron, staying in the land of Canaan.[6]

The five kingdoms of the plain had become vassal states of an alliance of four eastern kingdoms under the leadership of Chedorlaomer, king of Elam. They served this king for twelve years, but "in the thirteenth year they rebelled." The following year Chedorlaomer's four armies returned and at the Battle of Siddim the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah fell in defeat. Chedorlaomer despoiled the cities and took captives as he departed, including Lot, who dwelt in Sodom.[7]

When Abram heard what had happened to Lot, he led a force of three hundred and eighteen of his trained men and caught up to the armies of the four kings in Dan. Abram divided his forces and pursued them to Hobah. Abram brought back Lot and all of his people and their belongings.[8]

Sodom

[edit]

Later, after God had changed Abram's name to Abraham and Sarai's name to Sarah as part of the covenant of the pieces, God appeared to Abraham in the form of three angels. God promised Abraham that Sarah would bear a son, and he would become a great and mighty nation.[9] God then tells Abraham his plan,

"And the Lord said: 'Verily, the cry of Sodom and Gomorrah is great, and, verily, their sin is exceeding grievous. I will go down now and see whether they have done altogether according to the cry of it, which is come unto Me; and if not, I will know."

As the angels continued to walk toward Sodom, Abraham pled to God on behalf of the people of Sodom, where Lot dwelt. God assured him that the city would not be destroyed if fifty righteous people were found there. He continued inquiring, reducing the minimum number for sparing the town to forty-five, forty, thirty, twenty, and finally, ten.[10]

Lot's visitors

[edit]And the two angels came to Sodom in the evening; and Lot sat in the gate of Sodom; and Lot saw them, and rose up to meet them; and he fell down on his face to the earth; and he said: 'Behold now, my lords, turn aside, I pray you, into your servant's house, and tarry all night, and wash your feet, and ye shall rise up early, and go on your way.' And they said: 'Nay; but we will abide in the broad place all night.' And he urged them greatly; and they turned in unto him, and entered into his house; and he made them a feast, and did bake unleavened bread, and they did eat.

After supper, that night before bedtime, the men of the city, young and old, gathered around Lot's house demanding that he bring out his two guests that they may rape them. Lot went out, closing the door behind him, and begged them to refrain from so wicked a deed, offering them instead his virgin daughters to do with as they pleased. The men of Sodom accused Lot of acting as a judge and threatened to do worse to him than they would have done to the ‘men’.[11]

The angels drew Lot back in to his house and struck the mob with blindness. The angels then said that God had sent them to destroy the place, telling Lot, "whomsoever thou hast in the city; bring them out of the place". Lot went to the houses of his sons-in-law and warned them to leave the city, but they would not come, imagining that he spoke only in jest.[12]

Lot lingered in the morning so the angels forced him and his family out of the city, telling them to flee for the hills and not look back. Fearful that the hills would not afford them sufficient protection from the impending destruction, Lot instead asked the angels if he and his might hide in the safety of a neighboring village. An angel agreed and the village was thenceforth known as Zoar. When God rained fire and brimstone upon Sodom and Gomorrah, Lot's wife looked back at the burning cities of the plain and was turned into a pillar of salt in recompense for her folly.[13]

The sun was risen upon the earth when Lot came unto Zoar. Then the LORD caused to rain upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the LORD out of heaven; and He overthrow those cities, and all the Plain, and all the inhabitants of the cities, and that which grew upon the ground. But his wife looked back from behind him, and she became a pillar of salt. And Abraham got up early in the morning to the place where he had stood before the LORD. And he looked out toward Sodom and Gomorrah, and toward all the land of the Plain, and beheld, and, lo, the smoke of the land went up as the smoke of a furnace.

Instead of fire and brimstone, Josephus has only lightning as the cause of the fire that destroyed Sodom: "God then cast a thunderbolt upon the city, and set it on fire, with its inhabitants; and laid waste the country with the like burning."[14] In The Jewish War, he likewise says that the city was "burnt by lightning".[15]

Daughters

[edit]

After the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Lot was afraid to stay in Zoar and so he and his two daughters resettled into the hills, living in a cave.[16] Concerned for their father having descendants, one evening, Lot's eldest daughter gets Lot drunk and has sex with him without his knowledge. The elder daughter then insisted that her younger sister also get him drunk and have sex with him, which the younger sister duly did on the following night. From these incestuous unions, the older daughter conceived Moab (Hebrew מוֹאָב, lit., "from the father" [meh-Av]), father of the Moabites;[17] while the younger conceived Ben-Ammi (Hebrew בֶּן-עַמִּי, lit., "Son of my people"), father of the Ammonites.[18]

The story, usually called Lot and his daughters, has been the subject of many paintings over the centuries, and became one of the subjects in the Power of Women group of subjects, warning men against the dangers of succumbing to the temptations of women, while also providing an opportunity for an erotic depiction. The scene generally shows Lot and his daughters eating and drinking in their mountain refuge. Often the background contains a small figure of Lot's wife, and in the distance, a burning city.[19]

Along with the account of Tamar and Judah (Genesis 38:11–26), this is one instance of "sperm stealing" in the Bible, in which a woman seduces and has sex with her male relative under false pretenses in order to become pregnant. Each case involves a direct ancestor of King David.[20]

Religious views

[edit]

Jewish view

[edit]In the Bereshith of the Torah, Lot is first mentioned at the end of the weekly reading portion, Parashat Noach. The weekly reading portions that follow, concerning all of the accounts of Lot's life, are read in the Parashat Lekh Lekha and Parashat Vayera. In the Midrash, a number of additional stories concerning Lot are present, not found in the Tanakh, as follows:

- Abraham took care of Lot after Haran was burned in a gigantic fire in which Nimrod, King of Babylon, tried to kill Abraham.

- While in Egypt, the midrash gives Lot much credit because, despite his desire for wealth, he did not inform Pharaoh of Sarah's secret, that she was Abraham's wife.

- According to the Book of Jasher, Paltith, one of Lot's daughters, was burnt alive (in some versions, on a pyre) for giving a poor man bread.[21] Her cries went to the heavens.[22]

Christian view

[edit]In the Christian New Testament, Lot is considered sympathetically, as a man who regretted his choice to live in Sodom, where he "vexed his righteous soul from day to day".[23] Jesus spoke of future judgment coming suddenly as in the days of Lot, and warned solemnly, "Remember Lot's wife".[24]

Islamic view

[edit]

Lut (Arabic: لُوط – Lūṭ) in the Quran is considered to be the same as Lot in the Hebrew Bible. He is considered to be a messenger of God and a prophet of God.[25]

In Islamic tradition, Lut lived in Ur and was a nephew of Ibrahim (Abraham). He migrated with Ibrahim to Canaan and was commissioned as a prophet to the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah.[26] His story is used as a reference by Muslims to demonstrate God's disapproval of homosexuality. He was commanded by God to go to the land of Sodom and Gomorrah to preach monotheism and to stop them from their lustful and violent acts. Lut's messages were ignored by the inhabitants, prompting Sodom and Gomorrah's destruction. Though Lut left the city, his wife was left behind. The angels that had visited Lot previously informed him she would linger behind, and hence she died during the destruction. In Surah At-tahrim (the Prohibition) the wife of Lot is described as a disbeliever, and it is mentioned that she betrayed Lot (66:10).[26] The Quran defines Lot as a prophet, and holds that all prophets were examples of moral and spiritual rectitude.

20th-century views

[edit]

The presumptive incest between Lot and his daughters has raised many questions, debates, and theories as to what the real motives were, who really was at fault, and the level of bias the author of Genesis Chapter 19 had. However, such biblical scholars as Jacob Milgrom,[27] Victor P. Hamilton,[28] and Calum Carmichael[29] postulate that the Levitical laws could not have been developed the way they were, without controversial issues surrounding the patriarchs of Israel, especially regarding incest. Carmichael even attributes the entire formulation of the Levitical laws to the lives of the founding fathers of the nation, including the righteous Lot (together with Abraham, Jacob, Judah, Moses, and David), who were outstanding figures in Israelite tradition.

According to the scholars mentioned above, the patriarchs of Israel are the key to understanding how the priestly laws concerning incest developed. Kinship marriages amongst the patriarchs include Abraham's marriage to his half-sister Sarai;[30] the marriage of Abraham's brother, Nahor, to their niece Milcah;[31] Isaac's marriage to Rebekah, his first cousin once removed;[32] Jacob's marriages with two sisters who are his first cousins;[33] and, in the instance of Moses's parents, a marriage between nephew and paternal aunt.[34] Therefore, the patriarchal marriages surely mattered to lawgivers and they suggest a narrative basis for the laws of Leviticus, chapters 18 and 20.[35]

Some[who?] have argued that Lot's behavior in offering of his daughters to the men of Sodom in Genesis 19:8 constitutes sexual abuse of his daughters, which created a confusion of kinship roles that was ultimately played out through the incestuous acts in Genesis 19:30–38.[36]

A number of commentators describe the actions of Lot's daughters as rape. Esther Fuchs suggests that the text presents Lot's daughters as the "initiators and perpetrators of the incestuous 'rape'."[37]

See also

[edit]- Bani Na'im, Palestinian town containing alleged tomb of Lot

- Baucis and Philemon, Greek mythology figures with story similar to Lot's

- Biblical and Quranic narratives

- Biblical narrative: weekly Torah portions

- Lekh-lekha, 3rd weekly Torah portion containing the first part of the story of Abram and Lot

- Vayeira, 4th weekly Torah portion: last part of the story of Abram/Abraham and Lot, including destruction of Sodom

- Monastery of St Lot (5th-7th c.) at entrance to cave identified by Byzantine-period Christians as Lot's shelter

References

[edit]- ^ "H3875-6". Strong's Exhaustive Concordance – via Wikisource.

- ^ Mirabeau, Honoré (1867). Erotika Biblion. Chevalier de Pierrugues. Chez tous les Libraries.

- ^ Genesis 11:28–32

- ^ Genesis 12:5–9

- ^ Genesis 12:10–20

- ^ Genesis 13:1–12

- ^ Genesis 14:1–12

- ^ Genesis 14:13–24

- ^ Genesis 18:1–18

- ^ Genesis 18:22–33

- ^ Genesis 19:4–9

- ^ Genesis 19:10–14

- ^ Genesis 19:15–26

- ^ Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews 1.11.4. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Josephus. Wars of the Jews 4.8.4. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Genesis 19:30–38

- ^ Genesis 19:37

- ^ Genesis 19:38

- ^ Lowenthal, Anne W. (1988) "Lot and His Daughters as Moral Dilemma", in The Age of Rembrandt: Studies in Seventeenth-century Dutch Painting, Volume 3 of Papers in Art History from the Pennsylvania State University, eds. Roland E. Fleischer, Susan Scott Munshower. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0915773022

- ^ Yaron, Shlomith. "Sperm stealing: a moral crime by three of David's ancestresses". Bible Review 17:1, February 2001

- ^ Hirsch, Emil; Seligsohn, M.; et al. (1906) "Lot". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Kaminker, Mendy. "Sodom and Gomorrah: Cities Destroyed by G-d". Chabad.org. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ 2 Peter 2:6–9

- ^ Luke 17:28–33

- ^ Quran 26:161

- ^ a b Hasan, Masudul (1987). History of Islam, Volume 1. Islamic Publications. p. 26.

Lut was a nephew of the Prophet Abraham. He migrated with Abraham from Iraq to Canaan in Palestine. He was commissioned as a prophet to the cities of Sodom and Gomarrah, situated to the east of the Dead Sea. The people of these cities were guilty of unspeakable crimes. They were addicted to homosexuality and highway robberies. Lut warned the people but they refused to listen to him. He prayed to God to punish the people. Lot left the city with his followers at night.

- ^ Milgrom, Jacob (2000). Leviticus 17–22. Doubleday. pp. 1515–1520. ISBN 9780385412551.

- ^ Hamilton, Victor P. (1995). The Book of Genesis: Chapters 18–50. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802823090.[page needed]

- ^ Carmichael, Calum M. (1997). Law, Legend and Incest in the Bible: Leviticus 18-20. Cornell University Press. pp. 6, 14–18. ISBN 9780801433887.

- ^ Gen 20:11–12

- ^ Gen 11:27–29

- ^ Gen 27:42–43; 29:10

- ^ Gen 29:10

- ^ Exod 6:20

- ^ Kimuhu, Johnson M. (2008). Leviticus: The Priestly Laws and Prohibitions from the Perspective of Ancient Near East and Africa. Studies in Biblical Literature 115. Peter Lang. pp. 31–33.

- ^ Katherine B. Low (Fall 2010). "The Sexual Abuse of Lot's Daughters: Reconceptualizing Kinship for the Sake of Our Daughters". Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 26 (2). Indiana University Press: 37–54. doi:10.2979/fsr.2010.26.2.37. S2CID 143666743.

- ^ Fuchs, Esther (2003). Sexual Politics in the Biblical Narrative: Reading the Hebrew Bible as a Woman. A&C Black. p. 209. ISBN 9780567042873.

Bibliography

[edit]- Calmet, Augustin (1832). Calmet's Dictionary of the Holy Bible. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. p. 737. LCC BS440.C3.

- Drummond, Dorothy Weitz (2004). Holy Land, Whose Land?. Fairhurst Press. ISBN 9780974823324.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). The History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period, Volume 1: Yehud, the Persian Province of Judah. Continuum. pp. 105, 312. ISBN 9780567089984.

- West, Gerald (2003). "Ruth". In Dunn, James D.G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

External links

[edit]- Our People: A History of the Jews – Abram and Lot at chabad.org

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Easton's Bible Dictionary. 1897.

.jpg/232px-Reni_-_Lot_and_his_Daughters_leaving_Sodom,_about_1615-16_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)