Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stimulator of interferon genes

View on Wikipedia

Stimulator of interferon genes (STING), also known as transmembrane protein 173 (TMEM173) and MPYS/MITA/ERIS is a regulator protein that in humans is encoded by the STING1 gene.[5]

STING plays an important role in innate immunity. STING induces type I interferon production when cells are infected with intracellular pathogens, such as viruses, mycobacteria and intracellular parasites.[6] Type I interferon, mediated by STING, protects infected cells and nearby cells from local infection by binding to the same cell that secretes it (autocrine signaling) and nearby cells (paracrine signaling.) It thus plays an important role, for instance, in controlling norovirus infection.[7]

STING works as both a direct cytosolic DNA sensor (CDS) and an adaptor protein in Type I interferon signaling through different molecular mechanisms. It has been shown to activate downstream transcription factors STAT6 and IRF3 through TBK1, which are responsible for antiviral response and innate immune response against intracellular pathogen.[8]

Structure

[edit]

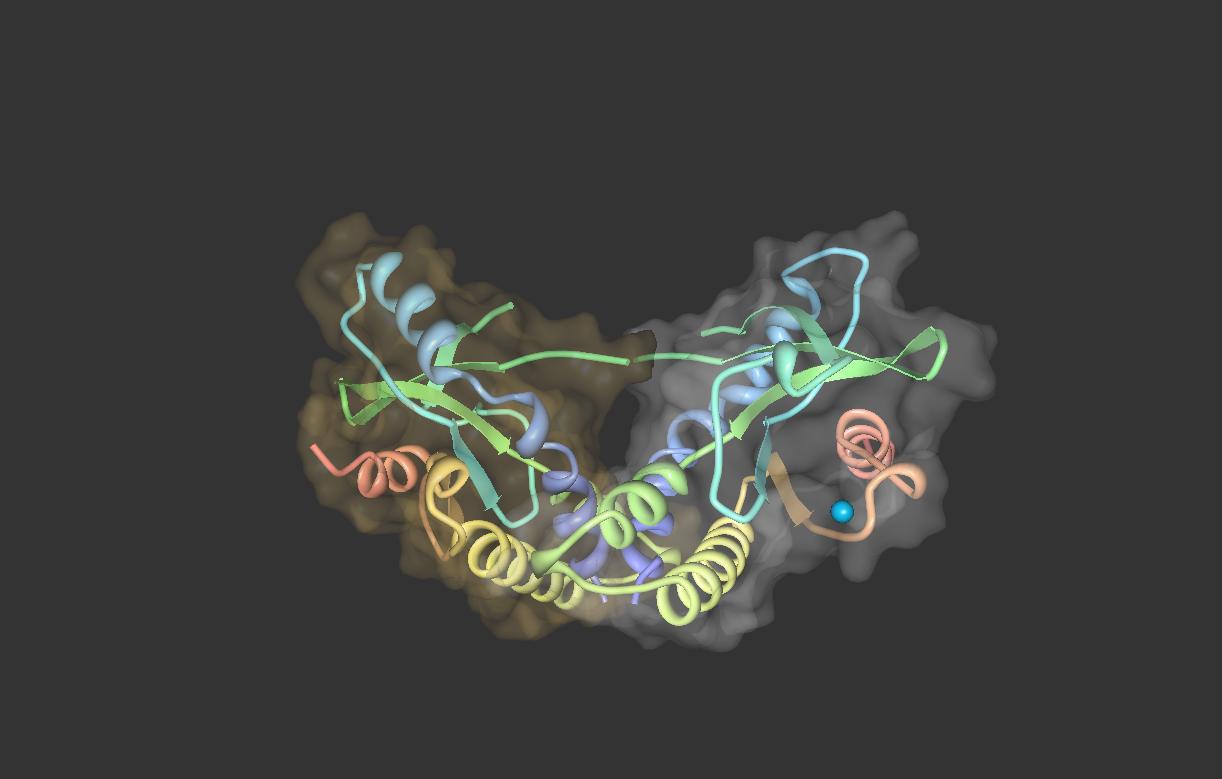

Amino acids 1–379 of human STING include the 4 transmembrane regions (TMs) and a C-terminal domain. The C-terminal domain (CTD: amino acids 138–379) contains the dimerization domain (DD) and the carboxy-terminal tail (CTT: amino acids 340–379).[8]

The STING forms a symmetrical dimer in the cell. STING dimer resembles a butterfly, with a deep cleft between the two protomers. The hydrophobic residues from each STING protomer form hydrophobic interactions between each other at the interface.[8][9]

Expression

[edit]STING is expressed in hematopoietic cells in peripheral lymphoid tissues, including T lymphocytes, NK cells, myeloid cells and monocytes. It has also been shown that STING is highly expressed in lung, ovary, heart, smooth muscle, retina, bone marrow and vagina.[10][11]

Localization

[edit]The subcellular localization of STING has been elucidated as an endoplasmic reticulum protein. Also, it is likely that STING associates in close proximity with mitochondria associated ER membrane (MAM)-the interface between the mitochondrion and the ER.[12] During intracellular infection, STING is able to relocalize from endoplasmic reticulum to perinuclear vesicles potentially involved in exocyst mediated transport.[12] STING has also been shown to colocalize with autophagy proteins, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) and autophagy-related protein 9A, after double-stranded DNA stimulation, suggesting its presence in the autophagosome.[13]

Function

[edit]STING mediates the type I interferon production in response to intracellular DNA and a variety of intracellular pathogens, including viruses, intracellular bacteria and intracellular parasites.[14] Upon infection, STING from infected cells can sense the presence of nucleic acids from intracellular pathogens, and then induce interferon β and more than 10 forms of interferon α production. Type I interferon produced by infected cells can find and bind to Interferon-alpha/beta receptor of nearby cells to protect cells from local infection.

Antiviral immunity

[edit]STING elicits powerful type I interferon immunity against viral infection. After viral entry, viral nucleic acids are present in the cytosol of infected cells. Several DNA sensors, such as DAI, RNA polymerase III, IFI16, DDX41 and cGAS, can detect foreign nucleic acids. After recognizing viral DNA, DNA sensors initiate the downstream signaling pathways by activating STING-mediated interferon response.[15]

Adenovirus, herpes simplex virus, HSV-1 and HSV-2, as well as the negative-stranded RNA virus, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), have been shown to be able to activate a STING-dependent innate immune response.[14]

STING deficiency in mice led to lethal susceptibility to HSV-1 infection due to the lack of a successful type I interferon response.[16]

Point mutation of serine-358 dampens STING-IFN activation in bats and is suggested to give bats their ability to serve as reservoir hosts.[17]

Against intracellular bacteria

[edit]Intracellular bacteria, Listeria monocytogenes, have been shown to stimulate host immune response through STING.[18] STING may play an important role in the production of MCP-1 and CCL7 chemokines. STING deficient monocytes are intrinsically defective in migration to the liver during Listeria monocytogenes infection. In this way, STING protects host from Listeria monocytogenes infection by regulating monocyte migration. The activation of STING is likely to be mediated by cyclic di-AMP secreted by intracellular bacteria.[18][19]

Other

[edit]STING may be an important molecule for protective immunity against infectious organisms. For example, animals that cannot express STING are more susceptible to infection from VSV, HSV-1 and Listeria monocytogenes, suggesting its potential correlation to human infectious diseases.[20]

Role in host immunity

[edit]Although type I IFN is absolutely critical for resistance to viruses, there is growing literature about the negative role of type I interferon in host immunity mediated by STING. AT-rich stem-loop DNA motif in the Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium berghei genome and extracellular DNA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis have been shown to activate type I interferon through STING.[21][22] Perforation of the phagosome membrane mediated by ESX1 secretion system allows extracellular mycobacterial DNA to access host cytosolic DNA sensors, thus inducing the production of type I interferon in macrophages. High type I interferon signature leads to the M. tuberculosis pathogenesis and prolonged infection.[22] STING-TBK1-IRF mediated type I interferon response is central to the pathogenesis of experimental cerebral malaria in laboratory animals infected with Plasmodium berghei. Laboratory mice deficient in type I interferon response are resistant to experimental cerebral malaria.[21]

STING signaling mechanisms

[edit]

STING mediates type I interferon immune response by functioning as both a direct DNA sensor and a signaling adaptor protein. Upon activation, STING stimulates TBK1 activity to phosphorylate IRF3 or STAT6. Phosphorylated IRF3s and STAT6s dimerize, and then enter nucleus to stimulate expression of genes involved in host immune response, such as IFNB, CCL2, CCL20, etc.[8][23]

Several reports suggested that STING is associated with the activation of selective autophagy.[13] Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been shown to produce cytosolic DNA ligands which activate STING, resulting in ubiquitination of bacteria and the subsequent recruitment of autophagy related proteins, all of which are required for 'selective' autophagic targeting and innate defense against M. tuberculosis.[24]

In summary, STING coordinates multiple immune responses to infection, including the induction of interferons and STAT6-dependent response and selective autophagy response.[8]

As a cytosolic DNA sensor

[edit]Cyclic dinucleotides-second-messenger signaling molecules produced by diverse bacterial species were detected in the cytosol of mammalian cells during intracellular pathogen infection; this leads to activation of TBK1-IRF3 and the downstream production of type I interferon.[8][25] STING has been shown to bind directly to cyclic di-GMP, and this recognition leads to the production of cytokines, such as type I interferon, that are essential for successful pathogen elimination.[26]

As a signaling adaptor

[edit]DDX41, a member of the DEXDc family of helicases, in myeloid dendritic cells recognizes intracellular DNA and mediates innate immune response through direct association with STING.[27] Other DNA sensors- DAI, RNA polymerase III, IFI16, have also been shown to activate STING through direct or indirect interactions.[15]

Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), which belongs to the nucleotidyltransferase family, is able to recognize cytosolic DNA contents and induce STING-dependent interferon response by producing secondary messenger cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate (cyclic GMP-AMP, or cGAMP). After cyclic GMP-AMP bound STING is activated, it enhances TBK1's activity to phosphorylate IRF3 and STAT6 for downstream type I interferon response.[28][29]

It has been proposed that intracellular calcium plays an important role in the response of the STING pathway.[30]

See also

[edit]- STING agonist – Component of the innate immune system

References

[edit]- ^ a b c ENSG00000288243 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000184584, ENSG00000288243 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000024349 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "STING1 stimulator of interferon response cGAMP interactor 1 [ Homo sapiens (human) ]".

- ^ Nakhaei P, Hiscott J, Lin R (Jun 2010). "STING-ing the antiviral pathway". Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 2 (3): 110–2. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjp048. PMID 20022884.

- ^ NYu P, Miao Z, Li Y, Bansal R, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q (2021). "cGAS-STING effectively restricts murine norovirus infection but antagonizes the antiviral action of N-terminus of RIG-I in mouse macrophage". Gut Microbes. 13 (1) 1959839. doi:10.1080/19490976.2021.1959839. ISSN 1949-0976. PMC 8344765. PMID 34347572.

- ^ a b c d e f Burdette DL, Vance RE (Jan 2013). "STING and the innate immune response to nucleic acids in the cytosol". Nature Immunology. 14 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1038/ni.2491. PMID 23238760. S2CID 7968532.

- ^ Shu C, Yi G, Watts T, Kao CC, Li P (Jul 2012). "Structure of STING bound to cyclic di-GMP reveals the mechanism of cyclic dinucleotide recognition by the immune system". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 19 (7): 722–4. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2331. PMC 3392545. PMID 22728658.

- ^ "EST expression profile of TMEM173". biogps org. biogps.org.

- ^ "NCBI TMEM173 expression GEOprofile". NCBI. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geoprofiles.

- ^ a b Ishikawa H, Barber GN (Oct 2008). "STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling". Nature. 455 (7213): 674–8. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..674I. doi:10.1038/nature07317. PMC 2804933. PMID 18724357.

- ^ a b Saitoh T, Fujita N, Hayashi T, Takahara K, Satoh T, Lee H, Matsunaga K, Kageyama S, Omori H, Noda T, Yamamoto N, Kawai T, Ishii K, Takeuchi O, Yoshimori T, Akira S (Dec 2009). "Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (49): 20842–6. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620842S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911267106. PMC 2791563. PMID 19926846.

- ^ a b Barber GN (Feb 2011). "Innate immune DNA sensing pathways: STING, AIMII and the regulation of interferon production and inflammatory responses". Current Opinion in Immunology. 23 (1): 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2010.12.015. PMC 3881186. PMID 21239155.

- ^ a b Keating SE, Baran M, Bowie AG (Dec 2011). "Cytosolic DNA sensors regulating type I interferon induction" (PDF). Trends in Immunology. 32 (12): 574–81. doi:10.1016/j.it.2011.08.004. hdl:2262/68041. PMID 21940216.

- ^ Ma Z, Damania B (February 2016). "The cGAS-STING Defense Pathway and Its Counteraction by Viruses". Cell Host & Microbe. 19 (2): 150–8. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.010. PMC 4755325. PMID 26867174.

- ^ Xie J, Li Y, Shen X, Got G, Zhu Y, Cui J, Wang L, Shi Z, Zhou P (March 2018). "Dampened STING-Dependent Interferon Activation in Bats". Cell Host & Microbe. 23 (3): 297–301.e4. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2018.01.006. PMC 7104992. PMID 29478775.

- ^ a b Jin L, Getahun A, Knowles HM, Mogan J, Akerlund LJ, Packard TA, Perraud AL, Cambier JC (Mar 2013). "STING/MPYS mediates host defense against Listeria monocytogenes infection by regulating Ly6C(hi) monocyte migration". Journal of Immunology. 190 (6): 2835–43. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1201788. PMC 3593745. PMID 23378430.

- ^ Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA (Jun 2010). "c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response". Science. 328 (5986): 1703–5. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1703W. doi:10.1126/science.1189801. PMC 3156580. PMID 20508090.

- ^ Ishikawa H, Ma Z, Barber GN (Oct 2009). "STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity". Nature. 461 (7265): 788–92. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..788I. doi:10.1038/nature08476. PMC 4664154. PMID 19776740.

- ^ a b Sharma S, DeOliveira RB, Kalantari P, Parroche P, Goutagny N, Jiang Z, Chan J, Bartholomeu DC, Lauw F, Hall JP, Barber GN, Gazzinelli RT, Fitzgerald KA, Golenbock DT (Aug 2011). "Innate immune recognition of an AT-rich stem-loop DNA motif in the Plasmodium falciparum genome". Immunity. 35 (2): 194–207. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.016. PMC 3162998. PMID 21820332.

- ^ a b Manzanillo PS, Shiloh MU, Portnoy DA, Cox JS (May 2012). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis activates the DNA-dependent cytosolic surveillance pathway within macrophages". Cell Host & Microbe. 11 (5): 469–80. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2012.03.007. PMC 3662372. PMID 22607800.

- ^ Chen H, Sun H, You F, Sun W, Zhou X, Chen L, Yang J, Wang Y, Tang H, Guan Y, Xia W, Gu J, Ishikawa H, Gutman D, Barber G, Qin Z, Jiang Z (Oct 2011). "Activation of STAT6 by STING is critical for antiviral innate immunity". Cell. 147 (2): 436–46. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.022. PMID 22000020.

- ^ Watson RO, Manzanillo PS, Cox JS (Aug 2012). "Extracellular M. tuberculosis DNA targets bacteria for autophagy by activating the host DNA-sensing pathway". Cell. 150 (4): 803–15. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.040. PMC 3708656. PMID 22901810.

- ^ McWhirter SM, Barbalat R, Monroe KM, Fontana MF, Hyodo M, Joncker NT, Ishii KJ, Akira S, Colonna M, Chen ZJ, Fitzgerald KA, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE (Aug 2009). "A host type I interferon response is induced by cytosolic sensing of the bacterial second messenger cyclic-di-GMP". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 206 (9): 1899–911. doi:10.1084/jem.20082874. PMC 2737161. PMID 19652017.

- ^ Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, Iwig JS, Eckert B, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE (Oct 2011). "STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP". Nature. 478 (7370): 515–8. Bibcode:2011Natur.478..515B. doi:10.1038/nature10429. PMC 3203314. PMID 21947006.

- ^ Zhang Z, Yuan B, Bao M, Lu N, Kim T, Liu YJ (Oct 2011). "The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells". Nature Immunology. 12 (10): 959–65. doi:10.1038/ni.2091. PMC 3671854. PMID 21892174.

- ^ Wu J, Sun L, Chen X, Du F, Shi H, Chen C, Chen ZJ (Feb 2013). "Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA". Science. 339 (6121): 826–30. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..826W. doi:10.1126/science.1229963. PMC 3855410. PMID 23258412.

- ^ Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ (Feb 2013). "Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway". Science. 339 (6121): 786–91. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..786S. doi:10.1126/science.1232458. PMC 3863629. PMID 23258413.

- ^ Kim S, Koch P, Li L, Peshkin L, Mitchison TJ (4 Jun 2017). "Evidence for a role of calcium in STING signaling". bioRxiv 10.1101/145854.

Further reading

[edit]- Wang Y, Tong X, Omoregie ES, Liu W, Meng S, Ye X (Oct 2012). "Tetraspanin 6 (TSPAN6) negatively regulates retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptor-mediated immune signaling in a ubiquitination-dependent manner". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (41): 34626–34. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.390401. PMC 3464568. PMID 22908223.

- Yin Q, Tian Y, Kabaleeswaran V, Jiang X, Tu D, Eck MJ, Chen ZJ, Wu H (Jun 2012). "Cyclic di-GMP sensing via the innate immune signaling protein STING". Molecular Cell. 46 (6): 735–45. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.029. PMC 3697849. PMID 22705373.

- Aguirre S, Maestre AM, Pagni S, Patel JR, Savage T, Gutman D, Maringer K, Bernal-Rubio D, Shabman RS, Simon V, Rodriguez-Madoz JR, Mulder LC, Barber GN, Fernandez-Sesma A (2012). "DENV inhibits type I IFN production in infected cells by cleaving human STING". PLOS Pathogens. 8 (10) e1002934. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002934. PMC 3464218. PMID 23055924.

- Li Y, Li C, Xue P, Zhong B, Mao AP, Ran Y, Chen H, Wang YY, Yang F, Shu HB (May 2009). "ISG56 is a negative-feedback regulator of virus-triggered signaling and cellular antiviral response". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (19): 7945–50. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.7945L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900818106. PMC 2683125. PMID 19416887.

- Conlon J, Burdette DL, Sharma S, Bhat N, Thompson M, Jiang Z, Rathinam VA, Monks B, Jin T, Xiao TS, Vogel SN, Vance RE, Fitzgerald KA (May 2013). "Mouse, but not human STING, binds and signals in response to the vascular disrupting agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid". Journal of Immunology. 190 (10): 5216–25. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300097. PMC 3647383. PMID 23585680.

- Abe T, Harashima A, Xia T, Konno H, Konno K, Morales A, Ahn J, Gutman D, Barber GN (Apr 2013). "STING recognition of cytoplasmic DNA instigates cellular defense". Molecular Cell. 50 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.039. PMC 3881179. PMID 23478444.

- Nazmi A, Mukhopadhyay R, Dutta K, Basu A (2012). "STING mediates neuronal innate immune response following Japanese encephalitis virus infection". Scientific Reports. 2 347. Bibcode:2012NatSR...2..347N. doi:10.1038/srep00347. PMC 3317237. PMID 22470840.

- Zhang J, Hu MM, Wang YY, Shu HB (Aug 2012). "TRIM32 protein modulates type I interferon induction and cellular antiviral response by targeting MITA/STING protein for K63-linked ubiquitination". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (34): 28646–55. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.362608. PMC 3436586. PMID 22745133.

- Ishikawa H, Barber GN (Oct 2008). "STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling". Nature. 455 (7213): 674–8. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..674I. doi:10.1038/nature07317. PMC 2804933. PMID 18724357.