Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Interferon regulatory factor 3, also known as IRF3, is an interferon regulatory factor.[5]

Function

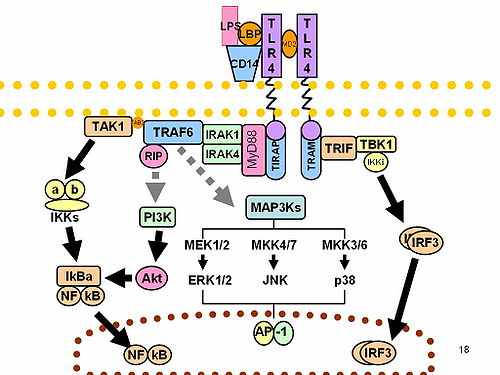

[edit]IRF3 is a member of the interferon regulatory transcription factor (IRF) family.[5] IRF3 was originally discovered as a homolog of IRF1 and IRF2. IRF3 has been further characterized and shown to contain several functional domains including a nuclear export signal, a DNA-binding domain, a C-terminal IRF association domain and several regulatory phosphorylation sites.[6] IRF3 is found in an inactive cytoplasmic form that upon serine/threonine phosphorylation forms a complex with CREBBP.[7] The complex translocates into the nucleus for the transcriptional activation of interferons alpha and beta, and further interferon-induced genes.[8]

IRF3 plays an important role in the innate immune system's response to viral infection.[9] Aggregated MAVS have been found to activate IRF3 dimerization.[10] A 2015 study shows phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING and TRIF at a conserved pLxIS motif recruits and specifies IRF3 phosphorylation and activation by the Serine/threonine-protein kinase TBK1, thereby activating the production of type-I interferons.[11] Another study has shown that IRF3-/- knockouts protect from myocardial infarction.[12] The same study identified IRF3 and the type I IFN response as a potential therapeutic target for post-myocardial infarction cardioprotection.[12]

Interactions

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000126456 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000003184 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Hiscott J, Pitha P, Genin P, Nguyen H, Heylbroeck C, Mamane Y, Algarte M, Lin R (1999). "Triggering the interferon response: the role of IRF-3 transcription factor". J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 19 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1089/107999099314360. PMID 10048763.

- ^ Lin R, Heylbroeck C, Genin P, Pitha PM, Hiscott J (Feb 1999). "Essential Role of Interferon Regulatory Factor 3 in Direct Activation of RANTES Chemokine Transcription". Mol Cell Biol. 19 (2): 959–66. doi:10.1128/MCB.19.2.959. PMC 116027. PMID 9891032.

- ^ Yoneyama M, Suhara W, Fujita T (2002). "Control of IRF-3 activation by phosphorylation". J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 22 (1): 73–6. doi:10.1089/107999002753452674. PMID 11846977.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: IRF3 interferon regulatory factor 3".

- ^ Collins SE, Noyce RS, Mossman KL (Feb 2004). "Innate Cellular Response to Virus Particle Entry Requires IRF3 but Not Virus Replication". J Virol. 78 (4): 1706–17. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.4.1706-1717.2004. PMC 369475. PMID 14747536.

- ^ Hou F, Sun L, Zheng H, Skaug B, Jiang QX, Chen ZJ (Aug 5, 2011). "MAVS Forms Functional Prion-Like Aggregates To Activate and Propagate Antiviral Innate Immune Response". Cell. 146 (3): 448–61. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.041. PMC 3179916. PMID 21782231.

- ^ Liu S, Cai X, Wu J, Cong Q, Chen X, Li T, Du F, Ren J, Wu Y, Grishin N, and Chen ZJ (Mar 13, 2015). "Phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF induces IRF3 activation". Science. 347 (6227) aaa2630. doi:10.1126/science.aaa2630. PMID 25636800.

- ^ a b King KR, Aguirre AD, Ye YX, Sun Y, Roh JD, Ng Jr RP, Kohler RH, Arlauckas SP, Iwamoto Y, Savol A, Sadreyev RI, Kelly M, Fitzgibbons TP, Fitzgerald KA, Mitchison T, Libby P, Nahrendorf M, Weissleder R (Nov 6, 2017). "IRF3 and type I interferons fuel a fatal response to myocardial infarction". Nature Medicine. 23 (12): 1481–1487. doi:10.1038/nm.4428. PMC 6477926. PMID 29106401.

- ^ Au WC, Yeow WS, Pitha PM (Feb 2001). "Analysis of functional domains of interferon regulatory factor 7 and its association with IRF-3". Virology. 280 (2): 273–82. doi:10.1006/viro.2000.0782. PMID 11162841.

Further reading

[edit]- Pitha PM, Au WC, Lowther W, Juang YT, Schafer SL, Burysek L, Hiscott J, Moore PA (1999). "Role of the interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) in virus-mediated signaling and regulation of cell growth". Biochimie. 80 (8–9): 651–8. doi:10.1016/S0300-9084(99)80018-2. PMID 9865487.

- Yoneyama M, Suhara W, Fujita T (2002). "Control of IRF-3 activation by phosphorylation". J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 22 (1): 73–6. doi:10.1089/107999002753452674. PMID 11846977.

- Au WC, Moore PA, Lowther W, Juang YT, Pitha PM (1996). "Identification of a member of the interferon regulatory factor family that binds to the interferon-stimulated response element and activates expression of interferon-induced genes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 (25): 11657–61. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.25.11657. PMC 40461. PMID 8524823.

- Yoneyama M, Suhara W, Fukuhara Y, Fukuda M, Nishida E, Fujita T (1998). "Direct triggering of the type I interferon system by virus infection: activation of a transcription factor complex containing IRF-3 and CBP/p300". EMBO J. 17 (4): 1087–95. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.4.1087. PMC 1170457. PMID 9463386.

- Weaver BK, Kumar KP, Reich NC (1998). "Interferon Regulatory Factor 3 and CREB-Binding Protein/p300 Are Subunits of Double-Stranded RNA-Activated Transcription Factor DRAF1". Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 (3): 1359–68. doi:10.1128/MCB.18.3.1359. PMC 108849. PMID 9488451.

- Lin R, Heylbroeck C, Pitha PM, Hiscott J (1998). "Virus-Dependent Phosphorylation of the IRF-3 Transcription Factor Regulates Nuclear Translocation, Transactivation Potential, and Proteasome-Mediated Degradation". Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 (5): 2986–96. doi:10.1128/MCB.18.5.2986. PMC 110678. PMID 9566918.

- Ronco LV, Karpova AY, Vidal M, Howley PM (1998). "Human papillomavirus 16 E6 oncoprotein binds to interferon regulatory factor-3 and inhibits its transcriptional activity". Genes Dev. 12 (13): 2061–72. doi:10.1101/gad.12.13.2061. PMC 316980. PMID 9649509.

- Bellingham J, Gregory-Evans K, Gregory-Evans CY (1999). "Mapping of human interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) to chromosome 19q13.3-13.4 by an intragenic polymorphic marker". Annals of Human Genetics. 62 (Pt 3): 231–4. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.1998.6230231.x. PMID 9803267. S2CID 46070705.

- Lowther WJ, Moore PA, Carter KC, Pitha PM (1999). "Cloning and functional analysis of the human IRF-3 promoter". DNA Cell Biol. 18 (9): 685–92. doi:10.1089/104454999314962. PMID 10492399.

- Kim T, Kim TY, Song YH, Min IM, Yim J, Kim TK (1999). "Activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 in response to DNA-damaging agents". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (43): 30686–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.43.30686. PMID 10521456.

- Kumar KP, McBride KM, Weaver BK, Dingwall C, Reich NC (2000). "Regulated Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Localization of Interferon Regulatory Factor 3, a Subunit of Double-Stranded RNA-Activated Factor 1". Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 (11): 4159–68. doi:10.1128/MCB.20.11.4159-4168.2000. PMC 85785. PMID 10805757.

- Suhara W, Yoneyama M, Iwamura T, Yoshimura S, Tamura K, Namiki H, Aimoto S, Fujita T (2000). "Analyses of virus-induced homomeric and heteromeric protein associations between IRF-3 and coactivator CBP/p300". J. Biochem. 128 (2): 301–7. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022753. PMID 10920266.

- Servant MJ, ten Oever B, LePage C, Conti L, Gessani S, Julkunen I, Lin R, Hiscott J (2001). "Identification of distinct signaling pathways leading to the phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor 3". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (1): 355–63. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007790200. PMID 11035028.

- Smith EJ, Marié I, Prakash A, García-Sastre A, Levy DE (2001). "IRF3 and IRF7 phosphorylation in virus-infected cells does not require double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase R or Ikappa B kinase but is blocked by Vaccinia virus E3L protein". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (12): 8951–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008717200. PMID 11124948.

- Au WC, Yeow WS, Pitha PM (2001). "Analysis of functional domains of interferon regulatory factor 7 and its association with IRF-3". Virology. 280 (2): 273–82. doi:10.1006/viro.2000.0782. PMID 11162841.

- Barnes BJ, Moore PA, Pitha PM (2001). "Virus-specific activation of a novel interferon regulatory factor, IRF-5, results in the induction of distinct interferon alpha genes". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (26): 23382–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.M101216200. PMID 11303025.

- Mach CM, Hargrove BW, Kunkel GR (2002). "The Small RNA gene activator protein, SphI postoctamer homology-binding factor/selenocysteine tRNA gene transcription activating factor, stimulates transcription of the human interferon regulatory factor-3 gene". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (7): 4853–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108308200. PMID 11724783.

- Morin P, Bragança J, Bandu MT, Lin R, Hiscott J, Doly J, Civas A (2002). "Preferential binding sites for interferon regulatory factors 3 and 7 involved in interferon-A gene transcription". J. Mol. Biol. 316 (5): 1009–22. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2001.5401. PMID 11884139.

- Dang O, Navarro L, Anderson K, David M (2004). "Cutting edge: anthrax lethal toxin inhibits activation of IFN-regulatory factor 3 by lipopolysaccharide". Journal of Immunology. 172 (2): 747–51. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.747. PMID 14707042.

External links

[edit]- Interferon+Regulatory+Factor-3 at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- FactorBook IRF3