Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Marshosaurus

View on Wikipedia

| Marshosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull cast | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Piatnitzkysauridae |

| Genus: | †Marshosaurus Madsen, 1976 |

| Species: | †M. bicentesimus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Marshosaurus bicentesimus Madsen, 1976

| |

Marshosaurus is a genus of carnivorous theropod dinosaur, belonging to the family Piatnitzkysauridae, from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of Utah and possibly Colorado.[1]

Discovery and naming

[edit]

During the 1960s, over fourteen thousand fossil bones were uncovered at the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry in central Utah. The majority of these belonged to Allosaurus but some were of at least two theropods new to science. In 1974 one of these was named by James Henry Madsen Jr. as the genus Stokesosaurus.

In 1976 the second was by Madsen named as the type species Marshosaurus bicentesimus. The generic name honoured the nineteenth century paleontologist Professor Othniel Charles Marsh, who described many dinosaur fossils during the Bone Wars. The specific name was chosen "in honor of the bicentennial of the United States of America".[1]

The holotype, UMNH VP 6373, was found in a layer of the Brushy Basin Member of the Morrison Formation dating from the late Kimmeridgian, approximately 155 - 152 mya. It is a left ilium, or upper pelvis bone. The paratypes consisted of three bones: the ischia UMNH VP 6379 and UMNH VP 380 and the pubic bone UMNH VP 6387. Three ilia and six jaw fragments were provisionally referred. The material represents at least three individuals.

In 1991, Brooks Britt referred tail vertebrae from Colorado, because they resembled non-identified tail vertebrae fragments from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry.[2] In 1993 a partial skeleton, CMNH 21704, from the Dinosaur National Monument was referred because its dorsal neural spines resembled non-identified spines from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry.[3] This specimen was also the subject of a 1997 SVP abstract.[4]

Description

[edit]

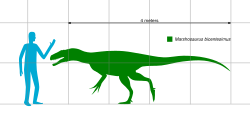

Marshosaurus was medium-sized for a theropod. In 2010, Gregory S. Paul estimated its length at 4.5 meters (15 ft) and its weight at 200 kilograms (440 lb).[5] The holotype ilium has a length of 37.5 centimeters (14.8 in). If the cranial material is correctly referred, the skull was about 60 centimeters (24 in) long.

In 2012, Matthew Carrano established one autapomorphy, a unique derived trait of the holotype: the suture between the pubic peduncle and the pubic bone is convex, curving upwards, at the front and concave at the rear.[6]

Classification

[edit]

Madsen originally was unsure about the phylogenetic position of Marshosaurus, placing it as Theropoda incertae sedis. Some later analyses showed Marshosaurus to be a member of Avetheropoda, a group of more bird-like theropods including Tyrannosaurus, Velociraptor and Allosaurus. However, Roger Benson (2010)[7] found it to be a megalosauroid in a phylogenetic analysis of Megalosaurus and 40 other theropods.

The position of Marshosaurus in the evolutionary tree, as a possible member of the Piatnitzkysauridae, is shown by the cladogram below.[7]

Paleobiology

[edit]

Pathology

[edit]One right ilium of a Marshosaurus bicentesimus is deformed by "an undescribed pathology" which probably originated as a consequence of injury. Another specimen has a pathological rib.[8] In a 2001 study conducted by Bruce Rothschild and other paleontologists, five foot bones referred to Marshosaurus were examined for signs of stress fracture, but none were found.[9]

Paleoecology

[edit]Habitat

[edit]The Morrison Formation is a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sediments which, according to radiometric dating, ranges between 156.3 million years old (Ma) at its base,[10] to 146.8 million years old at the top,[11] which places it in the late Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian, and early Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic period. This formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet and dry seasons. The Morrison Basin where dinosaurs lived, stretched from New Mexico to Alberta and Saskatchewan, and was formed when the precursors to the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains started pushing up to the west. The deposits from their east-facing drainage basins were carried by streams and rivers and deposited in swampy lowlands, lakes, river channels and floodplains.[12] This formation is similar in age to the Solnhofen Limestone Formation in Germany and the Tendaguru Formation in Tanzania. In 1877 this formation became the center of the Bone Wars, a fossil-collecting rivalry between early paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.

Paleofauna

[edit]The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs such as Camarasaurus, Brachiosaurus, Barosaurus, Diplodocus, and Apatosaurus. Dinosaurs that lived alongside Marshosaurus included the herbivorous ornithischians Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Stegosaurus and Othnielosaurus. Predators in this paleoenvironment included the theropods Saurophaganax, Torvosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Stokesosaurus, Ornitholestes and[13] Allosaurus, which accounted for 70 to 75% of theropod specimens and was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food web.[14] Stegosaurus is commonly found at the same sites as Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus.[15] Early mammals were present in this region, such as docodonts, multituberculates, symmetrodonts, and triconodonts. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of tree ferns, and ferns (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the Araucaria-like conifer Brachyphyllum.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Madsen, James H. (1976). "A second new theropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of east central Utah" (PDF). Utah Geology. 3 (1): 51–60. doi:10.34191/UG-3-1_51. S2CID 129534888.

- ^ Britt, Brooks (1991). "Theropods of Dry Mesa Quarry (Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic), Colorado, with emphasis on the osteology of Torvosaurus tanneri" (PDF). Brigham Young University Geology Studies. 37: 1–72.

- ^ Chure, D.; Britt, Brooks; Madsen, James H. (1993). "New data on the theropod Marshosaurus from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic: Kimmeridgian-Tithonian) of Dinosaur NM" (PDF). In Santucci (ed.). National Park Service Paleontology Research Abstract Volume. Technical Report NPS/NRPEFO/NRTR 93/11. p. 23.

- ^ Chure, D.; Britt, Brooks; Madsen, James H. (1997). "A new specimen of Marshosaurus bicentesimus (Theropoda) from the Morrison Formation (Late Jurassic) of Dinosaur National Monument". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (supp 3): 38A. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011028.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 91.

- ^ Carrano, Matthew T.; Benson, Roger B. J.; Sampson, Scott D. (2012). "The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 211–300. Bibcode:2012JSPal..10..211C. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.630927. S2CID 85354215.

- ^ a b Benson, Roger B. J. (2010). "A description of Megalosaurus bucklandii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bathonian of the UK and the relationships of Middle Jurassic theropods". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 158 (4): 882–935. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00569.x.

- ^ Molnar, R. E. (2001). "Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey". In Tanke, D. H.; Carpenter, K. (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press. pp. 337–363.

- ^ Rothschild, B.; Tanke, D. H.; Ford, T. L. (2001). "Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity". In Tanke, D. H.; Carpenter, K. (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press. pp. 331–336.

- ^ Trujillo, K. C.; Chamberlain, K. R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 38 (6): 7.

- ^ Bilbey, S. A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry - age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; Kirkland, J. I. (eds.). The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology. Vol. 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120. ISSN 0026-7775.

- ^ Russell, Dale A. (1989). An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America. Minocqua, Wisconsin: NorthWord Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-1-55971-038-1.

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix". Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327–329.

- ^ Foster, John R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- ^ Dodson, Peter; Behrensmeyer, A. K.; Bakker, Robert T.; McIntosh, John S. (1980). "Taphonomy and paleoecology of the dinosaur beds of the Jurassic Morrison Formation". Paleobiology. 6 (2): 208–232. doi:10.1017/s0094837300025768.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. Vol. 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.