Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Theropoda

View on Wikipedia

| Theropoda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gallery of theropods (clockwise from top left) Carnotaurus, Coelophysis, Irritator, Archaeopteryx, Struthiomimus and Tyrannosaurus | |||||

| Scientific classification | |||||

| Kingdom: | Animalia | ||||

| Phylum: | Chordata | ||||

| Class: | Reptilia | ||||

| Clade: | Dinosauria | ||||

| Clade: | Saurischia | ||||

| Clade: | Theropoda Marsh, 1881 | ||||

| Subgroups[1] | |||||

| |||||

Theropoda (/θɪəˈrɒpədə/;[2] from ancient Greek θηρίο- ποδός [θηρίον, (therion) "wild beast"; πούς, ποδός (pous, podos) "foot"]) is one of the three major clades of dinosaur, alongside Ornithischia and Sauropodomorpha. Theropods, both extant and extinct, are characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. They are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs, placing them closer to sauropodomorphs than to ornithischians. They were ancestrally carnivorous, although a number of theropod groups evolved to become herbivores and omnivores. Members of the subgroup Coelurosauria were most likely all covered with feathers, and it is possible that they were also present in other theropods. In the Jurassic, birds evolved from small specialized coelurosaurian theropods, and are currently represented by about 11,000 living species, making theropods the only group of dinosaurs alive today.

Theropods first appeared during the Carnian age of the Late Triassic period 231.4 million years ago (Ma)[3] and included the majority of large terrestrial carnivores from the Early Jurassic until the end of the Cretaceous, about 66 Ma, including the largest terrestrial carnivorous animals ever, such as Tyrannosaurus and Giganotosaurus, though non-avian theropods exhibited considerable size diversity, with some non-avian theropods like scansoriopterygids being no bigger than small birds.

Biology

[edit]Traits

[edit]Various synapomorphies for Theropoda have been proposed based on which taxa are included in the group. For example, a 1999 paper by Paul Sereno suggests that theropods are characterized by traits such as an ectopterygoid fossa (a depression around the ectopterygoid bone), an intramandibular joint located within the lower jaw, and extreme internal cavitation within the bones.[4] However, since taxa like Herrerasaurus may not be theropods, these traits may have been more widely distributed among early saurischians rather than being unique to theropods.

Instead, taxa with a higher probability of being within the Theropoda may share more specific traits, such as a prominent promaxillary fenestra, cervical vertebrae with pleurocoels in the anterior part of the centrum leading to a more pneumatic neck, five or more sacral vertebrae, enlargement of the carpal bone, and a distally concave portion of the tibia, among a few other traits found throughout the skeleton. Like the early sauropodomorphs, the second digit in a theropod's hand is enlarged. Theropods also have a very well developed ball and socket joint near their neck and head.[5][6]

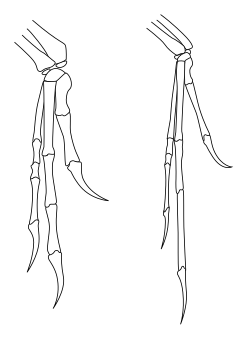

Most theropods belong to the clade Neotheropoda, characterized by the reduction of several foot bones, thus leaving three toed footprints on the ground when they walk (tridactyl feet). Digit V was reduced to a remnant early in theropod evolution and was gone by the late Triassic. Digit I is reduced and generally do not touch the ground, and greatly reduced in some lineages.[7] They also lack a digit V on their hands and have developed a furcula which is otherwise known as a wishbone.[5] Early neotheropods like the coelophysoids have a noticeable kink in the upper jaw known as a subnarial gap. Averostrans are some of the most derived theropods and contain the Tetanurae and Ceratosauria. While some used to consider coelophysoids and ceratosaurs to be within the same group due to features such as a fused hip, later studies showed that it is more likely that these were features ancestral to neotheropods and were lost in basal tetanurans.[8] Averostrans and their close relatives are united via the complete loss of any digit V remnants, fewer teeth in the maxilla, the movement of the tooth row further down the maxilla and a lacrimal fenestra. Averostrans also share features in their hips and teeth.[9]

Diet and teeth

[edit]

Theropods exhibit a wide range of diets, from insectivores to herbivores and carnivores. Strict carnivory has always been considered the ancestral diet for theropods as a group, and a wider variety of diets was historically considered a characteristic exclusive to the avian theropods (birds). However, discoveries in the late 20th and early 21st centuries showed that a variety of diets existed even in more basal lineages.[10] All early finds of theropod fossils showed them to be primarily carnivorous. Fossilized specimens of early theropods known to scientists in the 19th and early 20th centuries all possessed sharp teeth with serrated edges for cutting flesh, and some specimens even showed direct evidence of predatory behavior. For example, a Compsognathus longipes fossil was found with a lizard in its stomach, and a Velociraptor mongoliensis specimen was found locked in combat with a Protoceratops andrewsi (a type of ornithischian dinosaur). This was likely caused by a sand dune blowing over the two animals mid combat, resulting in fossilization.

The first confirmed non-carnivorous fossil theropods found were the therizinosaurs, originally known as "segnosaurs". First thought to be prosauropods, these enigmatic dinosaurs were later proven to be highly specialized, herbivorous theropods. Therizinosaurs possessed large abdomens for processing plant food, and small heads with beaks and leaf-shaped teeth. Further study of maniraptoran theropods and their relationships showed that therizinosaurs were not the only early members of this group to abandon carnivory. Several other lineages of early maniraptorans show adaptations for an omnivorous diet, including seed-eating (some troodontids) and insect-eating (many avialans and alvarezsaurs). Oviraptorosaurs, ornithomimosaurs and advanced troodontids were likely omnivorous as well, and some theropods (such as Masiakasaurus knopfleri and the spinosaurids) appear to have specialized in catching fish.[11][12]

Diet is largely deduced by the tooth morphology,[13] tooth marks on bones of the prey, and gut contents. Some theropods, such as Baryonyx, Lourinhanosaurus, ornithomimosaurs, and birds, are known to use gastroliths, or gizzard-stones.

The majority of theropod teeth are blade-like, with serration on the edges,[14] called ziphodont. Others are pachydont or folidont depending on the shape of the tooth or denticles.[14] The morphology of the teeth is distinct enough to tell the major families apart,[13] which indicate different diet strategies. An investigation in July 2015 discovered that what appeared to be "cracks" in their teeth were actually folds that helped to prevent tooth breakage by strengthening individual serrations as they attacked their prey.[15] The folds helped the teeth stay in place longer, especially as theropods evolved into larger sizes and had more force in their bite.[16][17]

Integument (skin, scales and feathers)

[edit]

Mesozoic theropods were also very diverse in terms of skin texture and covering. Feathers or feather-like structures (filaments) are attested in most lineages of coelurosaurs (see feathered dinosaur). However, outside the coelurosaurs, feathers may have been confined to the young, smaller species, or limited parts of the animal. Many larger theropods had skin covered in small, bumpy scales. In some species, these were interspersed with larger scales. This type of skin is best known in the ceratosaur Carnotaurus, which has been preserved with extensive skin impressions.[18] Osteoderms, scales with a bony core, are known from Ceratosaurus, which was discovered with segments of osteoderms on top of its neck and tail, probably forming a continuous row in life.[19] In carnosaurs rectangular scutate scales are known from the top of the feet and the underside of the tail in Concavenator, and from the underside of the neck in Allosaurus.[20]

There is evidence of some lineages of theropods being ancestrally feathered but losing them in favor of scales in later members. In tyrannosauroids, the early members Dilong and Yutyrannus are preserved with evidence of feathers, while in the later tyrannosaurids, like Tyrannosaurus, Tarbosaurus, Albertosaurus, Gorgosaurus, and Daspletosaurus, there is evidence of scales, though it is unknown if they lost all feathers entirely.[21]

The coelurosaur lineages most distant from birds had feathers that were relatively short and composed of simple, possibly branching filaments.[22] Simple filaments are also seen in therizinosaurs, which also possessed large, stiffened "quill"-like feathers. More fully feathered theropods, such as dromaeosaurids, usually retain scales only on the feet. Some species may have mixed feathers elsewhere on the body as well. Scansoriopteryx preserved scales near the underside of the tail,[23] and Juravenator may have been predominantly scaly with some simple filaments interspersed.[24] On the other hand, some theropods were completely covered with feathers, such as the anchiornithid Anchiornis, which even had feathers on the feet and toes.[25]

Based on a relationships between tooth size and skull length and also a comparison of the degree of wear of the teeth of non-avian theropods and modern lepidosaurs, it is concluded that theropods had lips that protected their teeth from the outside. Visually, the snouts of such theropods as Daspletosaurus had more similarities with lizards than crocodilians, which lack lips.[26]

Size

[edit]

Tyrannosaurus was for many decades the largest known theropod and best known to the general public. Since its discovery, however, a number of other giant carnivorous dinosaurs have been described, including Spinosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus, and Giganotosaurus.[27] The original Spinosaurus specimens (as well as newer fossils described in 2006) support the idea that Spinosaurus was probably 3 meters longer than Tyrannosaurus, though Tyrannosaurus might have been more massive than Spinosaurus.[28] Specimens such as Sue and Scotty are both estimated to be the heaviest theropods known to science. It is still not clear why these animals grew so heavy and bulky compared to the land predators that came before and after them.

The largest extant theropod is the common ostrich, up to 2.74 m (9 ft) tall and weighing between 90 and 130 kg (200 – 290 lb).[29] The smallest non-avian theropod known from adult specimens is the troodontid Anchiornis huxleyi, at 110 grams in weight and 34 centimeters (1 ft) in length.[25] When modern birds are included, the bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae) is smallest at 1.9 g and 5.5 cm (2.2 in) long.[30][31]

Recent theories propose that theropod body size shrank continuously over a period of 50 million years, from an average of 163 kilograms (359 lb) down to 0.8 kilograms (1.8 lb), eventually evolving into over 11,000 species of modern birds. This was based on evidence that theropods were the only dinosaurs to get continuously smaller, and that their skeletons changed four times as fast as those of other dinosaur species.[32][33]

Growth rates

[edit]In order to estimate the growth rates of theropods, scientists need to calculate both age and body mass of a dinosaur. Both of these measures can only be calculated through fossilized bone and tissue, so regression analysis and extant animal growth rates as proxies are used to make predictions. Fossilized bones exhibit growth rings that appear as a result of growth or seasonal changes, which can be used to approximate age at the time of death.[34] However, the amount of rings in a skeleton can vary from bone to bone, and old rings can also be lost at advanced age, so scientists need to properly control these two possibly confounding variables.

Body mass is harder to determine as bone mass only represents a small proportion of the total body mass of animals. One method is to measure the circumference of the femur, which in non-avian theropod dinosaurs has been shown to be a relatively proportional to quadrupedal mammals,[35] and use this measurement as a function of body weight, as the proportions of long bones like the femur grow proportionately with body mass.[35] The method of using extant animal bone proportion to body mass ratios to make predictions about extinct animals is known as the extant-scaling (ES) approach.[36] A second method, known as the volumetric-density (VD) approach, uses full-scale models of skeletons to make inferences about potential mass. The ES approach is better for wide-range studies including many specimens and doesn't require as much of a complete skeleton as the VD approach, but the VD approach allows scientists to better answer more physiological questions about the animal, such as locomotion and center of gravity.[36]

The current consensus is that non-avian theropods didn't exhibit a group wide growth rate, but instead had varied rates depending on their size. However, all non-avian theropods had faster growth rates than extant reptiles, even when modern reptiles are scaled up to the large size of some non-avian theropods. As body mass increases, the relative growth rate also increases. This trend may be due to the need to reach the size required for reproductive maturity.[37] For example, one of the smallest known theropods was Microraptor zhaoianus, which had a body mass of 200 grams, grew at a rate of approximately 0.33 grams per day.[38] A comparable reptile of the same size grows at half of this rate. The growth rates of medium-sized non-avian theropods (100–1000 kg) approximated those of precocial birds, which are much slower than altricial birds. Large theropods (1500–3500 kg) grew even faster, similar to rates displayed by eutherian mammals.[38] The largest non-avian theropods, like Tyrannosaurus rex, had similar growth dynamics to the largest living land animal today, the African elephant, which is characterized by a rapid period of growth until maturity, subsequently followed by slowing growth in adulthood.[39]

Stance and gait

[edit]

As a hugely diverse group of animals, the posture adopted by theropods likely varied considerably between various lineages through time.[40] All known theropods are bipedal, with the forelimbs reduced in length and specialized for a wide variety of tasks (see below). In modern birds, the body is typically held in a somewhat upright position, with the upper leg (femur) held parallel to the spine and with the forward force of locomotion generated at the knee. Scientists are not certain how far back in the theropod family tree this type of posture and locomotion extends.[40]

Non-avian theropods were first recognized as bipedal during the 19th century, before their relationship to birds was widely accepted. During this period, theropods such as carnosaurs and tyrannosaurids were thought to have walked with vertical femurs and spines in an upright, nearly erect posture, using their long, muscular tails as additional support in a kangaroo-like tripodal stance.[40] Beginning in the 1970s, biomechanical studies of extinct giant theropods cast doubt on this interpretation. Studies of limb bone articulation and the relative absence of trackway evidence for tail dragging suggested that, when walking, the giant, long-tailed theropods would have adopted a more horizontal posture with the tail held parallel to the ground.[40][41] However, the orientation of the legs in these species while walking remains controversial. Some studies support a traditional vertically oriented femur, at least in the largest long-tailed theropods,[41] while others suggest that the knee was normally strongly flexed in all theropods while walking, even giants like the tyrannosaurids.[42][43] It is likely that a wide range of body postures, stances, and gaits existed in the many extinct theropod groups.[40][44]

Nervous system and senses

[edit]Although rare, complete casts of theropod endocrania are known from fossils. Theropod endocrania can also be reconstructed from preserved brain cases without damaging valuable specimens by using a computed tomography scan and 3D reconstruction software. These finds are of evolutionary significance because they help document the emergence of the neurology of modern birds from that of earlier reptiles. An increase in the proportion of the brain occupied by the cerebrum seems to have occurred with the advent of the Coelurosauria and "continued throughout the evolution of maniraptorans and early birds."[45]

Studies show that theropods had very sensitive snouts. It is suggested they might have been used for temperature detection, feeding behavior, and wave detection.[46][47]

Forelimb morphology

[edit]

Shortened forelimbs in relation to hind legs were a common trait among theropods, most notably in the abelisaurids (such as Carnotaurus) and the tyrannosaurids (such as Tyrannosaurus). This trait was, however, not universal: spinosaurids had well developed forelimbs, as did many coelurosaurs. The relatively robust forelimbs of one genus, Xuanhanosaurus, led Dong Zhiming to suggest that the animal might have been quadrupedal.[48] However, this is no longer thought to be likely.[49]

The hands are also very different among the different groups. The most common form among non-avian theropods is an appendage consisting of three fingers; the digits I, II and III (or possibly II, III and IV), with sharp claws. Some basal theropods, like most Ceratosaurians, had four digits, and also a reduced metacarpal V (e.g. Dilophosaurus). The majority of tetanurans had three,[a][50] but some had even fewer.[51]

The forelimbs' scope of use is also believed to have also been different among different families. The spinosaurids could have used their powerful forelimbs to hold fish. Some small maniraptorans such as scansoriopterygids are believed to have used their forelimbs to climb in trees.[23] The wings of modern birds are used primarily for flight, though they are adapted for other purposes in certain groups. For example, aquatic birds such as penguins use their wings as flippers.

Forelimb movement

[edit]

Contrary to the way theropods have often been reconstructed in art and the popular media, the range of motion of theropod forelimbs was severely limited, especially compared with the forelimb dexterity of humans and other primates.[52] Most notably, theropods and other bipedal saurischian dinosaurs (including the bipedal prosauropods) could not pronate their hands—that is, they could not rotate the forearm so that the palms faced the ground or backwards towards the legs. In humans, pronation is achieved by motion of the radius relative to the ulna (the two bones of the forearm). In saurischian dinosaurs, however, the end of the radius near the elbow was actually locked into a groove of the ulna, preventing any movement. Movement at the wrist was also limited in many species, forcing the entire forearm and hand to move as a single unit with little flexibility.[53] In theropods and prosauropods, the only way for the palm to face the ground would have been by lateral splaying of the entire forelimb, as in a bird raising its wing.[52]

In carnosaurs like Acrocanthosaurus, the hand itself retained a relatively high degree of flexibility, with mobile fingers. This was also true of more basal theropods, such as herrerasaurs. Coelurosaurs showed a shift in the use of the forearm, with greater flexibility at the shoulder allowing the arm to be raised towards the horizontal plane, and to even greater degrees in flying birds. However, in coelurosaurs, such as ornithomimosaurs and especially dromaeosaurids, the hand itself had lost most flexibility, with highly inflexible fingers. Dromaeosaurids and other maniraptorans also showed increased mobility at the wrist not seen in other theropods, thanks to the presence of a specialized half-moon shaped wrist bone (the semi-lunate carpal) that allowed the whole hand to fold backward towards the forearm in the manner of modern birds.[53]

Paleopathology

[edit]In 2001, Ralph E. Molnar published a survey of pathologies in theropod dinosaur bone. He found pathological features in 21 genera from 10 families. Pathologies were found in theropods of all body size although they were less common in fossils of small theropods, although this may be an artifact of preservation. They are very widely represented throughout the different parts of theropod anatomy. The most common sites of preserved injury and disease in theropod dinosaurs are the ribs and tail vertebrae. Despite being abundant in ribs and vertebrae, injuries seem to be "absent... or very rare" on the bodies' primary weight supporting bones like the sacrum, femur, and tibia. The lack of preserved injuries in these bones suggests that they were selected by evolution for resistance to breakage. The least common sites of preserved injury are the cranium and forelimb, with injuries occurring in about equal frequency at each site. Most pathologies preserved in theropod fossils are the remains of injuries like fractures, pits, and punctures, often likely originating with bites. Some theropod paleopathologies seem to be evidence of infections, which tended to be confined only to small regions of the animal's body. Evidence for congenital malformities have also been found in theropod remains. Such discoveries can provide information useful for understanding the evolutionary history of the processes of biological development. Unusual fusions in cranial elements or asymmetries in the same are probably evidence that one is examining the fossils of an extremely old individual rather than a diseased one.[54]

Swimming

[edit]The trackway of a swimming theropod, the first in China of the ichnogenus named Characichnos, was discovered at the Feitianshan Formation in Sichuan.[55] These swim tracks support the hypothesis that theropods were adapted to swimming and capable of traversing moderately deep water. Dinosaur swim tracks are considered to be rare trace fossils, and are among a class of vertebrate swim tracks that also include those of pterosaurs and crocodylomorphs. The study described and analyzed four complete natural molds of theropod foot prints that are now stored at the Huaxia Dinosaur Tracks Research and Development Center (HDT). These dinosaur footprints were in fact claw marks, which suggest that this theropod was swimming near the surface of a river and just the tips of its toes and claws could touch the bottom. The tracks indicate a coordinated, left-right, left-right progression, which supports the proposition that theropods were well-coordinated swimmers.[55]

Evolutionary history

[edit]

During the late Triassic, a number of primitive proto-theropod and theropod dinosaurs existed and evolved alongside each other.

The earliest and most primitive of the theropod dinosaurs were the carnivorous Eodromaeus and, possibly, the herrerasaurids of Argentina. The herrerasaurs existed during the early late Triassic (Late Carnian to Early Norian). They were found in North America and South America and possibly also India and Southern Africa. The herrerasaurs were characterised by a mosaic of primitive and advanced features. Some paleontologists have in the past considered the herrerasaurians to be members of Theropoda, while other theorized the group to be basal saurischians, and may even have evolved prior to the saurischian-ornithischian split. Cladistic analysis following the discovery of Tawa, another Triassic dinosaur, suggests the herrerasaurs likely were early theropods.[56]

The earliest and most primitive unambiguous theropods are the Coelophysoidea. The coelophysoids were a group of widely distributed, lightly built and potentially gregarious animals. They included small hunters like Coelophysis and Camposaurus. These successful animals continued from the Late Carnian (early Late Triassic) through to the Toarcian (late Early Jurassic). Although in the early cladistic classifications they were included under the Ceratosauria and considered a side-branch of more advanced theropods,[57] they may have been ancestral to all other theropods (which would make them a paraphyletic group).[58][59]

Neotheropoda (meaning "new theropods") is a clade that includes coelophysoids and more advanced theropod dinosaurs, and is the only group of theropods that survived the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. Neotheropoda was named by R.T. Bakker in 1986 as a group including the relatively derived theropod subgroups Ceratosauria and Tetanurae, and excluding coelophysoids.[60] However, most later researchers have used it to denote a broader group. Neotheropoda was first defined as a clade by Paul Sereno in 1998 as Coelophysis plus modern birds, which includes almost all theropods except the most primitive species.[61] Dilophosauridae was formerly considered a small clade within Neotheropoda, but was later considered to be paraphyletic. By the Early Jurassic, all non-averostran neotheropods had gone extinct.[62]

Averostra (or "bird snouts") is a clade within Neotheropoda that includes most theropod dinosaurs, namely Ceratosauria and Tetanurae. It represents the only group of post-Early Jurassic theropods. One important diagnostic feature of Averostra is the absence of the fifth metacarpal. Other saurischians retained this bone, albeit in a significantly reduced form.[63]

The somewhat more advanced ceratosaurs (including Ceratosaurus and Carnotaurus) appeared during the Early Jurassic and continued through to the Late Jurassic in Laurasia. They competed alongside their more anatomically advanced tetanuran relatives and—in the form of the abelisaur lineage—lasted to the end of the Cretaceous in Gondwana.

The Tetanurae are more specialised again than the ceratosaurs. They are subdivided into the basal Megalosauroidea (alternately Spinosauroidea) and the more derived Avetheropoda. Megalosauridae were primarily Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous predators, and their spinosaurid relatives' remains are mostly from Early and Middle Cretaceous rocks. Avetheropoda, as their name indicates, were more closely related to birds and are again divided into the Allosauroidea (the diverse carcharodontosaurs) and the Coelurosauria (a very large and diverse dinosaur group including the birds).

Thus, during the late Jurassic, there were no fewer than four distinct lineages of theropods—ceratosaurs, megalosaurs, allosaurs, and coelurosaurs—preying on the abundance of small and large herbivorous dinosaurs. All four groups survived into the Cretaceous, and three of those—the ceratosaurs, coelurosaurs, and allosaurs—survived to end of the period, where they were geographically separate, the ceratosaurs and allosaurs in Gondwana, and the coelurosaurs in Laurasia.

Of all the theropod groups, the coelurosaurs were by far the most diverse. Some coelurosaur groups that flourished during the Cretaceous were the tyrannosaurids (including Tyrannosaurus), the dromaeosaurids (including Velociraptor and Deinonychus, which are remarkably similar in form to one of the oldest known birds, Archaeopteryx),[64][65] the bird-like troodontids and oviraptorosaurs, the ornithomimosaurs (or "ostrich Dinosaurs"), the strange giant-clawed herbivorous therizinosaurs, and the avialans, which include modern birds and is the only dinosaur lineage to survive the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.[66] While the roots of these various groups are found in the Middle Jurassic, they only became abundant during the Early Cretaceous. A few palaeontologists, such as Gregory S. Paul, have suggested that some or all of these advanced theropods were actually descended from flying dinosaurs or proto-birds like Archaeopteryx that lost the ability to fly and returned to a terrestrial habitat.[67]

The evolution of birds from other theropod dinosaurs has also been reported, with some of the linking features being the furcula (wishbone), pneumatized bones, brooding of the eggs, and (in coelurosaurs, at least) feathers.[32][33][68]

Classification

[edit]History of classification

[edit]

O. C. Marsh coined the name Theropoda (meaning "beast feet") in 1881.[69] Marsh initially named Theropoda as a suborder to include the family Allosauridae, but later expanded its scope, re-ranking it as an order to include a wide array of "carnivorous" dinosaur families, including Megalosauridae, Compsognathidae, Ornithomimidae, Plateosauridae and Anchisauridae (now known to be herbivorous sauropodomorphs) and Hallopodidae (subsequently revealed as relatives of crocodilians). Due to the scope of Marsh's Order Theropoda, it came to replace a previous taxonomic group that Marsh's rival E. D. Cope had created in 1866 for the carnivorous dinosaurs: Goniopoda ("angled feet").[49]

By the early 20th century, some palaeontologists, such as Friedrich von Huene, no longer considered carnivorous dinosaurs to have formed a natural group. Huene abandoned the name "Theropoda", instead using Harry Seeley's Order Saurischia, which Huene divided into the suborders Coelurosauria and Pachypodosauria. Huene placed most of the small theropod groups into Coelurosauria, and the large theropods and prosauropods into Pachypodosauria, which he considered ancestral to the Sauropoda (prosauropods were still thought of as carnivorous at that time, owing to the incorrect association of rauisuchian skulls and teeth with prosauropod bodies, in animals such as Teratosaurus).[49] Describing the first known dromaeosaurid (Dromaeosaurus albertensis) in 1922,[70] W. D. Matthew and Barnum Brown became the first paleontologists to exclude prosauropods from the carnivorous dinosaurs, and attempted to revive the name "Goniopoda" for that group, but other scientists did not accept either of these suggestions.[49]

In 1956, "Theropoda" came back into use—as a taxon containing the carnivorous dinosaurs and their descendants—when Alfred Romer re-classified the Order Saurischia into two suborders, Theropoda and Sauropoda. This basic division has survived into modern palaeontology, with the exception of, again, the Prosauropoda, which Romer included as an infraorder of theropods. Romer also maintained a division between Coelurosauria and Carnosauria (which he also ranked as infraorders). This dichotomy was upset by the discovery of Deinonychus and Deinocheirus in 1969, neither of which could be classified easily as "carnosaurs" or "coelurosaurs". In light of these and other discoveries, by the late 1970s Rinchen Barsbold had created a new series of theropod infraorders: Coelurosauria, Deinonychosauria, Oviraptorosauria, Carnosauria, Ornithomimosauria, and Deinocheirosauria.[49]

With the advent of cladistics and phylogenetic nomenclature in the 1980s, and their development in the 1990s and 2000s, a clearer picture of theropod relationships began to emerge. Jacques Gauthier named several major theropod groups in 1986, including the clade Tetanurae for one branch of a basic theropod split with another group, the Ceratosauria. As more information about the link between dinosaurs and birds came to light, the more bird-like theropods were grouped in the clade Maniraptora (also named by Gauthier in 1986[57]). These new developments also came with a recognition among most scientists that birds arose directly from maniraptoran theropods and, on the abandonment of ranks in cladistic classification, with the re-evaluation of birds as a subset of theropod dinosaurs that survived the Mesozoic extinctions and lived into the present.[49]

Major groups

[edit]

The following is a simplified classification of theropod groups based on their evolutionary relationships, and organized based on the list of Mesozoic dinosaur species provided by Holtz.[1] A more detailed version can be found at dinosaur classification. The dagger (†) is used to signify groups with no living members.

- †Coelophysoidea (small, early theropods; includes Coelophysis and close relatives)

- †Ceratosauria (generally elaborately horned, the dominant southern carnivores of the Cretaceous; includes Carnotaurus and close relatives, like Majungasaurus and Chenanisaurus)

- Tetanurae ("stiff tails"; includes most theropods)

- †Megalosauroidea (early group of large carnivores including the semi-aquatic spinosaurids)

- †Allosauroidea (Allosaurus and close relatives, like Carcharodontosaurus)

- †Megaraptora (A group of medium to large Orionides with unknown affinities, quite common in the southern hemisphere)

- Coelurosauria (feathered theropods, with a range of body sizes and niches)

- †Compsognathidae (early coelurosaurs with reduced forelimbs)

- †Tyrannosauroidea (Tyrannosaurus and close relatives; had reduced forelimbs)

- †Ornithomimosauria ("ostrich-mimics"; mostly toothless; carnivores to possible herbivores)

- Maniraptora ("hand snatchers"; had long, slender arms and fingers)

- †Alvarezsauroidea (small insectivores with reduced forelimbs each bearing one enlarged claw)

- †Therizinosauria (bipedal herbivores with large hand claws and small heads)

- †Scansoriopterygidae (small, arboreal maniraptors with long third fingers)

- †Oviraptorosauria (mostly toothless; their diet and lifestyle are uncertain)

- Paraves ("near-birds"; generally carnivorous, sickle-claws)

- †Anchiornithidae (small, winged protobirds)

- †Dromaeosauridae (small to medium-sized theropods)

- †Troodontidae (small, gracile theropods)

- Avialae (birds and extinct relatives)

- †Omnivoropterygidae (large, early short-tailed avialans)

- †Confuciusornithidae (small toothless birds)

- †Enantiornithes (primitive tree-dwelling, flying birds)

- Euornithes (advanced flying birds)

- †Yanornithiformes (toothed Cretaceous Chinese birds)

- †Hesperornithes (specialized aquatic diving birds)

- Aves (modern, beaked birds and their extinct relatives)

Relationships

[edit]The following family tree illustrates a synthesis of the relationships of the major theropod groups based on various studies conducted in the 2010s.[72]

| Theropoda | |

Averostra was named by G.S. Paul in 2002 as an apomorphy-based clade defined as the group including the Dromaeosauridae and other Avepoda with (an ancestor with) a promaxillary fenestra (fenestra promaxillaris) which can also be referred to as a maxillary fenestra,[73] an extra opening in the front outer side of the maxilla, the bone that makes up the upper jaw.[74] It was later re-defined by Martin Ezcurra and Gilles Cuny in 2007 as a node-based clade containing Ceratosaurus nasicornis, Allosaurus fragilis, their last common ancestor and all its descendants.[75] Mickey Mortimer commented that Paul's original apomorphy-based definition may make Averostra a much broader clade than the Ceratosaurus+Allosaurus node, potentially including all of Avepoda or more.[76]

A large study of early dinosaurs by Dr Matthew G. Baron, David Norman and Paul M. Barrett (2017) published in the journal Nature suggested that Theropoda is actually more closely related to Ornithischia, to which it formed the sister group within the clade Ornithoscelida. This new hypothesis also recovered Herrerasauridae as the sister group to Sauropodomorpha in the redefined Saurischia and suggested that the hypercarnivore morphologies that are observed in specimens of theropods and herrerasaurids were acquired convergently.[77][78] However, this phylogeny remains controversial and additional work is being done to clarify these relationships.[79]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Some genera within Avetheropoda, however, had four digits, see ""Theropoda I" on Avetheropoda". Department of Geology. University of Maryland. 14 July 2006.

See also

[edit]- Feathered dinosaurs

- Origin of birds

- Other major clades of dinosaur

References

[edit]- ^ a b Holtz, Thomas R., Jr. (Winter 2011). "Appendix" (PDF). Dinosaurs: The most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages (published 2012).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Theropoda". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Martínez, Ricardo N.; Sereno, Paul C.; Alcober, Oscar A.; Colombi, Carina E.; Renne, Paul R.; Montañez, Isabel P.; Currie, Brian S. (2011). "A basal dinosaur from the dawn of the dinosaur era in Southwestern Pangaea". Science. 331 (6014): 206–210. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..206M. doi:10.1126/science.1198467. hdl:11336/69202. PMID 21233386. S2CID 33506648.

- ^ Sereno, Paul C. (25 June 1999). "The evolution of dinosaurs". Science. 284 (5423): 2137–2147. doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2137. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10381873.

- ^ a b Novas, Fernando E.; Agnolin, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Temp Müller, Rodrigo; Martinelli, Agustín G.; Langer, Max C. (1 October 2021). "Review of the fossil record of early dinosaurs from South America, and its phylogenetic implications". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 110 103341. Bibcode:2021JSAES.11003341N. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103341. ISSN 0895-9811.

- ^ Dingus, Lowell; Rowe, Timothy (1998). The mistaken extinction: Dinosaur evolution and the origin of birds. New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-2944-0.

- ^ Harris, J.D. (1997). "Four-toed theropod footprints and a paleomagnetic age from the Whetstone Falls Member of the Harebell Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Maastrichtian), northwestern Wyoming" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 18 (1): 139. doi:10.1006/cres.1996.0053 – via Dixie State University, St. George, UT.

(Saurexallopus lovei)

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R.; Rey, Luis V. (2007). Dinosaurs: the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- ^ SMITH, NATHAN D.; MAKOVICKY, PETER J.; HAMMER, WILLIAM R.; CURRIE, PHILIP J. (October 2007). "Osteology of Cryolophosaurus ellioti (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Jurassic of Antarctica and implications for early theropod evolution". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 151 (2): 377–421. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00325.x. ISSN 1096-3642.

- ^ Zanno, Lindsay E.; Gillette, David D.; Albright, L. Barry; Titus, Alan L. (25 August 2010). "A new North American therizinosaurid and the role of herbivory in 'predatory' dinosaur evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1672): 3505–3511. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1029. PMC 2817200. PMID 19605396.

- ^ Longrich, Nicholas R.; Currie, Philip J. (February 2009). "Albertonykus borealis, a new alvarezsaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Maastrichtian of Alberta, Canada: Implications for the systematics and ecology of the Alvarezsauridae". Cretaceous Research. 30 (1): 239–252. Bibcode:2009CrRes..30..239L. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2008.07.005.

- ^ Holtz, T. R. Jr.; Brinkman, D. L.; Chandler, C. L. (1998). "Dental morphometrics and a possibly omnivorous feeding habit for the theropod dinosaur Troodon". GAIA. 15: 159–166.

- ^ a b Hendrickx, C; Mateus, O (2014). "Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal and dentition-based phylogeny as a contribution for the identification of isolated theropod teeth". Zootaxa. 3759: 1–74. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3759.1.1. PMID 24869965. S2CID 12650231.

- ^ a b Hendrickx, Christophe; Mateus, Octávio; Araújo, Ricardo (2015). "A proposed terminology of theropod teeth (Dinosauria, Saurischia)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (Submitted manuscript). 35 e982797. Bibcode:2015JVPal..35E2797H. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.982797. S2CID 85774247.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (28 July 2015). "One tough bite: T. rex's teeth had secret weapon". Fox News. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ "Special Serrations Gave Carnivorous Dinosaurs an Evolutionary Edge". 17 August 2015. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015.

- ^ Brink, K. S.; Reisz, R. R.; Leblanc, A. R. H.; Chang, R. S.; Lee, Y. C.; Chiang, C. C.; Huang, T.; Evans, D. C. (2015). "Developmental and evolutionary novelty in the serrated teeth of theropod dinosaurs". Scientific Reports. 5 12338. Bibcode:2015NatSR...512338B. doi:10.1038/srep12338. PMC 4648475. PMID 26216577. S2CID 17247595.

- ^ Hendrickx, Christophe; Bell, Phil R. (1 December 2021). "The scaly skin of the abelisaurid Carnotaurus sastrei (Theropoda: Ceratosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 128 104994. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12804994H. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104994. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Gilmore, Charles W. (1920). "Osteology of the carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with special reference to the genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus". Bulletin of the United States National Museum (110): i–159. doi:10.5479/si.03629236.110.i. hdl:10088/10107.

- ^ Hendrickx, Christophe; Bell, Phil R.; Pittman, Michael; Milner, Andrew R. C.; Cuesta, Elena; O'Connor, Jingmai; Loewen, Mark; Currie, Philip J.; Mateus, Octávio; Kaye, Thomas G.; Delcourt, Rafael (2022). "Morphology and distribution of scales, dermal ossifications, and other non-feather integumentary structures in non-avialan theropod dinosaurs". Biological Reviews. 97 (3): 960–1004. doi:10.1111/brv.12829. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 34991180.

- ^ Bell, Phil R.; Campione, Nicolás E.; Persons, W. Scott; Currie, Philip J.; Larson, Peter L.; Tanke, Darren H.; Bakker, Robert T. (7 June 2017). "Tyrannosauroid integument reveals conflicting patterns of gigantism and feather evolution". Biology Letters. 13 (6) 20170092. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0092. PMC 5493735. PMID 28592520.

- ^ Göhlich, U.B.; Chiappe, L.M. (16 March 2006). "A new carnivorous dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Solnhofen archipelago" (PDF). Nature. 440 (7082): 329–332. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..329G. doi:10.1038/nature04579. PMID 16541071. S2CID 4427002 – via doc.rero.ch.

- ^ a b Czerkas, S.A.; Yuan, C. (2002). "An arboreal maniraptoran from northeast China" (PDF). In Czerkas, S.J. (ed.). Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight. The Dinosaur Museum Journal. Vol. 1. Blanding, UT: The Dinosaur Museum. pp. 63–95.

- ^ Goehlich, U.B.; Tischlinger, H.; Chiappe, L.M. (2006). "Juraventaor starki (Reptilia, Theropoda) ein nuer Raubdinosaurier aus dem Oberjura der Suedlichen Frankenalb (Sueddeutschland): Skelettanatomie und Wiechteilbefunde". Archaeopteryx. 24: 1–26.

- ^ a b Xu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Norell, M.; Sullivan, C.; Hone, D.; Erickson, G.; Wang, X.; Han, F. & Guo, Y. (February 2009). "A new feathered maniraptoran dinosaur fossil that fills a morphological gap in avian origin". Chinese Science Bulletin. 54 (3): 430–435. Bibcode:2009SciBu..54..430X. doi:10.1007/s11434-009-0009-6. Abstract

- ^ Cullen, Thomas M.; Larson, Derek William; Witton, Mark P.; Scott, Diane; Maho, Tea; Brink, Kirstin S.; et al. (30 March 2023). "Theropod dinosaur facial reconstruction and the importance of soft tissues in paleobiology". Science. 379 (6639): 1348–1352. Bibcode:2023Sci...379.1348C. doi:10.1126/science.abo7877. PMID 36996202. S2CID 257836765.

- ^ Therrien, F.; Henderson, D. M. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86025320.

- ^ dal Sasso, C.; Maganuco, S.; Buffetaut, E.; Mendez, M. A. (2005). "New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (Submitted manuscript). 25 (4): 888–896. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0888:NIOTSO]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85702490.

- ^ "Ostrich". African Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Brusatte SL, O'Connor JK, Jarvis ED (October 2015). "The origin and diversification of birds". Current Biology. 25 (19): R888–98. Bibcode:2015CBio...25.R888B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.003. hdl:10161/11144. PMID 26439352. S2CID 3099017.

- ^ Hendry, Lisa (2023). "Are birds the only surviving dinosaurs?". The Trustees of The Natural History Museum, London. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ a b Borenstein, Seth (31 July 2014). "Study traces dinosaur evolution into early birds". AP News. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b Zoe Gough (31 July 2014). "Dinosaurs 'shrank' regularly to become birds". BBC.

- ^ Padian, Kevin; de Ricqlès, Armand J.; Horner, John R. (July 2001). "Dinosaurian growth rates and bird origins". Nature. 412 (6845): 405–408. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..405P. doi:10.1038/35086500. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11473307. S2CID 4335246.

- ^ a b Anderson, J.F.; Hall-Martin, A.; Russell, D.A. (1985). "Long-bone circumference and weight in mammals, birds and dinosaurs". Journal of Zoology. 207 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1985.tb04915.x. ISSN 1469-7998.

- ^ a b Campione, Nicolás E.; Evans, David C. (2020). "The accuracy and precision of body mass estimation in non-avian dinosaurs". Biological Reviews. 95 (6): 1759–1797. doi:10.1111/brv.12638. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 32869488. S2CID 221404013.

- ^ Lee, Andrew H.; Werning, Sarah (15 January 2008). "Sexual maturity in growing dinosaurs does not fit reptilian growth models". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (2): 582–587. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105..582L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708903105. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2206579. PMID 18195356.

- ^ a b Erickson, Gregory M.; Rogers, Kristina Curry; Yerby, Scott A. (July 2001). "Dinosaurian growth patterns and rapid avian growth rates". Nature. 412 (6845): 429–433. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..429E. doi:10.1038/35086558. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11473315. S2CID 4319534. (Erratum: doi:10.1038/nature16488, PMID 26675731, Retraction Watch)

- ^ Horner, John R.; Padian, Kevin (22 September 2004). "Age and growth dynamics of Tyrannosaurus rex". Proceedings of the Royal Society. B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1551): 1875–1880. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2829. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1691809. PMID 15347508.

- ^ a b c d e Hutchinson, J.R. (March–April 2006). "The evolution of locomotion in archosaurs" (PDF). Comptes Rendus Palevol. 5 (3–4): 519–530. Bibcode:2006CRPal...5..519H. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2005.09.002.

- ^ a b Newman, B.H. (1970). "Stance and gait in the flesh-eating Tyrannosaurus". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2 (2): 119–123. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1970.tb01707.x.

- ^ Padian, K.; Olsen, P.E. (1989). "Ratite footprints and the stance and gait of Mesozoic theropods". In Gillette, D.D.; Lockley, M.G. (eds.). Dinosaur Tracks and Traces. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–241.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (1998). "Limb design, function and running performance in ostrich-mimics and tyrannosaurs". Gaia. 15: 257–270.

- ^ Farlow, J. O.; Gatesy, S. M.; Holtz, T. R. Jr.; Hutchinson, J. R.; Robinson, J. M. (2000). "Theropod locomotion". Am. Zool. 40 (4): 640–663. doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.640.

- ^ "Abstract", in Chure (2001). Pg. 19.[full citation needed]

- ^ Barker, Chris Tijani; Naish, Darren; Newham, Elis; Katsamenis, Orestis L.; Dyke, Gareth (16 June 2017). "Complex neuroanatomy in the rostrum of the Isle of Wight theropod Neovenator salerii". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 3749. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.3749B. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-03671-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5473926. PMID 28623335.

- ^ Kawabe, Soichiro; Hattori, Soki (3 July 2022). "Complex neurovascular system in the dentary of Tyrannosaurus". Historical Biology. 34 (7): 1137–1145. Bibcode:2022HBio...34.1137K. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.1965137. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 238728702.

- ^ Dong, Z. (1984). "A new theropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Sichuan Basin". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 22 (3): 213–218.

- ^ a b c d e f Rauhut, O.W. (2003). The Interrelationships and Evolution of Basal Theropod Dinosaurs. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-901702-79-X.

- ^ Barta, D.E.; Nesbitt, S.J.; Norell, M.A. (2017). "The evolution of the manus of early theropod dinosaurs is characterized by high inter- and intraspecific variation". Journal of Anatomy. 232 (1): 80–104. doi:10.1111/joa.12719. PMC 5735062. PMID 29114853.

- ^ "The first single-fingered dinosaur". phys.org. January 2011.

- ^ a b Carpenter, K. (2002). "Forelimb biomechanics of nonavian theropod dinosaurs in predation". Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 82 (1): 59–76. doi:10.1007/BF03043773. S2CID 84702973.

- ^ a b Senter, P.; Robins, J.H. (July 2005). "Range of motion in the forelimb of the theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, and implications for predatory behaviour". Journal of Zoology. 266 (3). London, UK: 307–318. doi:10.1017/S0952836905006989.

- ^ Molnar, R.E. (2001). "Theropod paleopathology: A literature survey". In Tanke, D.H.; Carpenter, K. (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press. pp. 337–363.

- ^ a b Xing, L.D.; Lockley, M.G.; Zhang, J.P.; et al. (2013). "A new Early Cretaceous dinosaur track assemblage and the first definite non-avian theropod swim trackway from China". Chin Sci Bull. 58 (19): 2370–2378. Bibcode:2013ChSBu..58.2370X. doi:10.1007/s11434-013-5802-6.

- ^ Nesbitt, S.J.; Smith, N.D.; Irmis, R.B.; Turner, A.H.; Downs, A. & Norell, M.A. (11 December 2009). "A complete skeleton of a Late Triassic saurischian and the early evolution of dinosaurs". Science. 326 (5959): 1530–1533. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1530N. doi:10.1126/science.1180350. PMID 20007898. S2CID 8349110..

- ^ a b Rowe, T. & Gauthier, J. (1990). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P. & Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria. Berkeley, CA / Los Angeles, CA / Oxford, UK: University of California Press. pp. 151–168.

- ^ Mortimer, M. (4 July 2001). "Rauhut's Thesis". dml.cmnh.org. Dinosaur Mailing List Archives.

- ^ Carrano, M.T.; Sampson, S.D.; Forster, C.A. (2002). "The osteology of Masiakasaurus knopfleri, a small abelisauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 510–534. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0510:TOOMKA]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85655323.

- ^ Bakker, R.T. (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies (PDF). New York, NY: William Morrow – via doc.rero.ch.

- ^ Sereno, P. (1998). "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria". Abhandlungen. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie (annual). 210: 41–83. doi:10.1127/njgpa/210/1998/41.

- ^ Marsh, Adam D.; Rowe, Timothy B. (2020). "A comprehensive anatomical and phylogenetic evaluation of Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Dinosauria, Theropoda) with descriptions of new specimens from the Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona". Journal of Paleontology. 94 (S78): 1–103. Bibcode:2020JPal...94S...1M. doi:10.1017/jpa.2020.14. S2CID 220601744.

- ^ Sasso, Cristiano Dal; Maganuco, Simone; Cau, Andrea (19 December 2018). "The oldest ceratosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda), from the Lower Jurassic of Italy, sheds light on the evolution of the three-fingered hand of birds". PeerJ. 6 e5976. doi:10.7717/peerj.5976. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6304160. PMID 30588396.

- ^ Ostrom, J.H. (1969). "Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an unusual theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana". Peabody Museum Natural History Bulletin. 30: 1–165.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster Co. ISBN 0-671-61946-2.

- ^ Dingus, L.; Rowe, T. (1998). The Mistaken Extinction: Dinosaur evolution and the origin of birds. Freeman.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (2002). Dinosaurs of the Air: The evolution and loss of flight in dinosaurs and birds. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6763-0.

- ^ Lee, MichaelS.Y.; Cau, Andrea; Naish, Darren; Dyke, Gareth J. (1 August 2014). "Sustained miniaturization and anatomical innovation in the dinosaurian ancestors of birds". Science. 345 (6196): 562–566. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..562L. doi:10.1126/science.1252243. PMID 25082702. S2CID 37866029.

- ^ Marsh, O.C. (1881). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part V.". The American Journal of Science and Arts. 3. 21 (125): 417–423. Bibcode:1881AmJS...21..417M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-21.125.417. S2CID 219234316.

- ^ Matthew, W.D.; Brown, B. (1922). "The family Deinodontidae, with notice of a new genus from the Cretaceous of Alberta". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 46: 367–385.

- ^ Anderson, Ted R. (2006). Biology of the Ubiquitous House Sparrow: from Genes to Populations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-530411-X.

- ^ Hendrickx, C.; Hartman, S.A.; Mateus, O. (2015). "An overview of non-avian theropod discoveries and classification". PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 12 (1): 1–73.

- ^ Carr, Thomas (22 October 2013). "Osteology VIII: The antorbital cavity". Tyrannosauroidea central. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (2002). Dinosaurs of the Air. Baltimore, MD / London, UK: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6763-7 – via Google books.

- ^ Ezcurra, M.D.; Cuny, G. (2007). "The coelophysoid Lophostropheus airelensis, gen. nov.: A review of the systematics of "Liliensternus" airelensis from the Triassic-Jurassic outcrops of Normandy (France)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 73–86. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[73:TCLAGN]2.0.CO;2 – via researchgate.net.

- ^ Mortimer, Mickey (15 November 2010). "Averostra and Avepoda". The Theropod Database Blog. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Baron, M.G.; Norman, D.B.; Barrett, P.M. (2017). "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution" (PDF). Nature. 543 (7646): 501–506. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..501B. doi:10.1038/nature21700. PMID 28332513. S2CID 205254710. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "New study shakes the roots of the dinosaur family tree". cam.ac.uk. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge. 22 March 2017.

- ^ Langer, M.C.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Rauhut, O.W.M.; Benton, M.J.; Knoll, F.; McPhee, B.W.; et al. (2017). "Untangling the dinosaur family tree". Nature. 551 (7678): E1 – E3. Bibcode:2017Natur.551E...1L. doi:10.1038/nature24011. hdl:1983/d088dae2-c7fa-4d41-9fa2-aeebbfcd2fa3. PMID 29094688. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

External links

[edit] Media related to Theropoda at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Theropoda at Wikimedia Commons