Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Coelophysoidea

View on Wikipedia

| Coelophysoids Temporal range: Late Triassic-Early Jurassic, Possible Toarcian records due to uncertainty in age of Panguraptor

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of Coelophysis bauri, Cleveland Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Neotheropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Coelophysoidea Nopcsa, 1928 |

| Type species | |

| †Coelophysis bauri Cope, 1887

| |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Coelophysoidea is an extinct clade of theropod dinosaurs common during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods. They were widespread geographically, probably living on all continents. Coelophysoids were all slender, carnivorous forms with a superficial similarity to the coelurosaurs, with which they were formerly classified, and some species had delicate cranial crests. Sizes range from about 1 to 6 m in length. It is unknown what kind of external covering coelophysoids had, and various artists have portrayed them as either scaly or feathered. Some species may have lived in packs, as inferred from sites where numerous individuals have been found together.

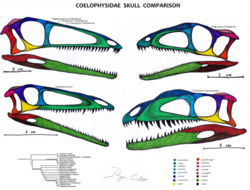

Examples of coelophysoids include Coelophysis, Procompsognathus and Liliensternus. Most dinosaurs formerly referred to as being in the dubious taxon "Podokesauridae" are now classified as coelophysoids. The family Coelophysidae, which is contained within Coelophysoidea, flourished in the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods, and has been found on numerous continents. Many members of Coelophysidae are characterized by long, slender skulls and light skeletons built for speed.[1] One member genus, Coelophysis, displays the earliest known furcula in a dinosaur.[2]

History of Study

[edit]Under cladistic analysis, Coelophysidae was first defined by Paul Sereno in 1998 as the most recent common ancestor of Coelophysis bauri and Procompsognathus triassicus, and all of that common ancestor's descendants.[1] However, Tykoski (2005) has advocated for the definition to change to include the additional taxa of "Syntarsus" kayentakatae and Segisaurus halli.[3] Coelophysidae is part of the superfamily Coelophysoidea, which in turn is a subset of the larger Neotheropoda clade.[1] As part of Coelophysoidea, Coelophysidae is often placed as sister to the Dilophosauridae family, however, the monophyly of this clade has often been disputed.[1] The older term "Podokesauridae", named 14 years prior to Coelophysidae (which would normally grant it priority), is now usually ignored, since its type specimen was destroyed in a fire and can no longer be compared to new finds.[4]

Anatomy

[edit]

Despite their very early occurrence in the fossil record (early to middle Norian),[5] coelophysoids have a number of derived features that separate them from primitive (basal) theropods. Among the most prominent of these derived features (apomorphies) is the way the upper jaw bones are connected (the premaxilla-maxilla articulation), which is flexible with a deep gap between the teeth in the two bones. A major source of disagreement among theropod experts is whether or not coelophysoids shared a more recent common ancestor with Ceratosauria (sensu stricto) than the ceratosaurs did with other theropods. Most recent analyses indicate the latter, that Coelophysoidea does not form a natural group with the ceratosaurians. Similarly, while Dilophosaurus and similar theropods have traditionally been classified as coelophysoids, several studies published in the late 2000s suggested that they may actually be more closely related to the tetanurans.[6]

Coelophysids are characterized by slender, skinny builds and long, narrow skulls with large fenestrae to allow for a lighter skull.[7] They are fairly primitive theropods, and so have fairly basal characteristics, such as hollow air sacs in the cervical vertebrae and obligate bipedalism.[7] Their slender builds allowed them to be fast and agile runners. All known members of Coelophysidae are carnivores. One species, Coelophysis bauri has the oldest known furcula (wishbone) of any dinosaur.[2]

It has also been speculated that some species within Coelophysidae, namely Coelophysis bauri, displayed cannibalism, although the fossil evidence behind these claims has been heavily debated (Rinehart et al., 2009; Gay, 2002; Gay, 2010).[8][9][10]

Classification

[edit]Coelophysoids are classified as basal neotheropods that lie outside of Averostra.[11] Many taxa that have been historically considered coelophysoids or coelophysids, have also been found elsewhere around the early theropod stem. Below is the phylogenetic analysis of Stephan Spiekman and colleagues from 2021, with taxa sometimes recovered as coelophysoids illustrated.[12][13]

| Theropoda |

| |||||||||||||

Paleoecology

[edit]

Fossils of members of Coelophysidae have been found across many continents, including North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa. Powellvenator podocitus was discovered in Northwestern Argentina.[14] Procompsognathus triassicus was discovered in Germany, and Camposaurus arizonensis is from Arizona in North America.[15][5] No coelophysid fossils were known from Asia until the discovery of Panguraptor lufengensis in 2014 in the Yunnan Province of China.[16] The genus Coelophysis has been found in North America, South Africa, and Zimbabwe.[17]

See also

[edit]- Eucoelophysis, an unrelated silesaurid

- Pangaea, the supercontinent where coelophysoids originated

- Timeline of coelophysoid research

- Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Hendrickx, C.; Hartman, S.A.; Mateus, O. (2015). "An overview of non-avian theropod discoveries and classification". PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 12 (1): 1–73. ISSN 1567-2158.

- ^ a b Rinehart, L.F.; Lucas, S.G.; Hunt, A.P. (2007). "Furculae in the Late Triassic theropod dinosaur Coelophysis bauri". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 81 (2): 174–180. Bibcode:2007PalZ...81..174R. doi:10.1007/BF02988391.

- ^ Tykoski, Ronald S. (2005). Anatomy, Ontogeny, and Phylogeny of Coelophysoid Theropods (PhD). University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ Sereno, P. (1999). "Taxon Search: Coelophysidae Archived 2007-10-07 at the Wayback Machine". Accessed 2009-09-02.

- ^ a b Ezcurra, M.D.; Brusatte, S.L. (2011). "Taxonomic and phylogenetic reassessment of the early neotheropod dinosaur Camposaurus arizonensis from the Late Triassic of North America". Palaeontology. 54 (4): 763–772. Bibcode:2011Palgy..54..763E. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01069.x.

- ^ Smith, N.D., Makovicky, P.J., Pol, D., Hammer, W.R., and Currie, P.J. (2007). "The dinosaurs of the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of the Central Transantarctic Mountains: Phylogenetic review and synthesis." In Cooper, A.K. and Raymond, C.R. et al. (eds.), Antarctica: A Keystone in a Changing World––Online Proceedings of the 10th ISAES, USGS Open-File Report 2007-1047, Short Research Paper 003, 5 p.; doi:10.3133/of2007-1047.srp003.

- ^ a b Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Smith, Nathan D.; Irmis, Randall B.; Turner, Alan H.; Downs, Alex; Norell, Mark A. (2009). "A Complete Skeleton of a Late Triassic Saurischian and the Early Evolution of Dinosaurs". Science. 326 (5959): 1530–1533. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1530N. doi:10.1126/science.1180350. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 20007898.

- ^ Rinehart, L.F.; Lucas, S.G.; Heckert, A.B.; Spielmann, J.A.; Celesky, M.D. (2009). "The paleobiology of Coelophysis bauri (Cope) from the Upper Triassic (Apachean) Whitaker quarry, New Mexico, with detailed analysis of a single quarry block". New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, A Division of the Department of Cultural Affairs Bulletin. 45: 260.

- ^ Gay, R.J. (2002). "The myth of cannibalism in Coelophysis bauri". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 57A.

- ^ Gay, R.J. (2010). Notes on Early Mesozoic Theropods (First ed.). Lulu press. pp. 9-24. ISBN 978-0-557-46616-0

- ^ Ezcurra, Martín D; Butler, Richard J; Maidment, Susannah C R; Sansom, Ivan J; Meade, Luke E; Radley, Jonathan D (2021-01-01). "A revision of the early neotheropod genus Sarcosaurus from the Early Jurassic (Hettangian–Sinemurian) of central England". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 191 (1): 113–149. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa054. hdl:11336/160038. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Tykoski, R.S.; Rowe, T.B. (2004). "Ceratosauria". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). University of California Press. pp. 47–70. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ Spiekman, S.N.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Butler, R.J.; Fraser, N.C.; Maidment, S.C.R. (2021). "Pendraig milnerae, a new small-sized coelophysoid theropod from the Late Triassic of Wales". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (10): 1–27. Bibcode:2021RSOS....810915S. doi:10.1098/rsos.210915. PMC 8493203. PMID 34754500.

- ^ Ezcurra, Martín D. (2017). "A New Early Coelophysoid Neotheropod from the Late Triassic of Northwestern Argentina". Ameghiniana. 54 (5): 506–538. Bibcode:2017Amegh..54..506E. doi:10.5710/amgh.04.08.2017.3100. hdl:11336/56719. ISSN 0002-7014.

- ^ Knoll, Fabien (2008). "On the Procompsognathus postcranium (Late Triassic, Germany)". Geobios. 41 (6): 779–786. Bibcode:2008Geobi..41..779K. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2008.02.002. ISSN 0016-6995.

- ^ You, Hai-Lu; Azuma, Yoichi; Wang, Tao; Wang, Ya-Ming; Dong, Zhi-Ming (2014-10-16). "The first well-preserved coelophysoid theropod dinosaur from Asia". Zootaxa. 3873 (3). doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3873.3.3. ISSN 1175-5334.

- ^ Bristowe, A.; Raath, M.A. (2004). "A juvenile coelophysoid skull from the Early Jurassic of Zimbabwe, and the synonymy of Coelophysis and Syntarsus". Palaeontologica Africana. 40: 31–41.

Sources

[edit]- Rauhut and Hungerbuhler (2000). "A review of European Triassic theropods." Gaia, 15: 75-88.

- Tykoski, R. S. (2005). "Anatomy, Ontogeny, and Phylogeny of Coelophysoid Theropods." Ph. D dissertation.

- Yates, A.M., 2006 (for 2005). "A new theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa and its implications for the early evolution of theropods." Palaeontologia Africana, 41: 105-122.