Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

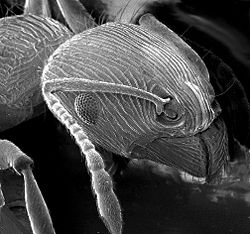

Electron microscope

View on Wikipedia

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of electrons as a source of illumination. It uses electron optics that are analogous to the glass lenses of an optical light microscope to control the electron beam, for instance focusing it to produce magnified images or electron diffraction patterns. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times smaller than that of visible light, electron microscopes have a much higher resolution of about 0.1 nm, which compares to about 200 nm for light microscopes.[1] Electron microscope may refer to:

- Transmission electron microscope (TEM) where swift electrons go through a thin sample

- Scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) which is similar to TEM with a scanned electron probe

- Scanning electron microscope (SEM) which is similar to STEM, but with thick samples

- Electron microprobe similar to a SEM, but more for chemical analysis

- Low-energy electron microscope (LEEM), used to image surfaces

- Photoemission electron microscope (PEEM) which is similar to LEEM using electrons emitted from surfaces by photons

Additional details can be found in the above links. This article contains some general information mainly about transmission and scanning electron microscopes.

History

[edit]Many developments laid the groundwork of the electron optics used in microscopes.[2] One significant step was the work of Hertz in 1883[3] who made a cathode-ray tube with electrostatic and magnetic deflection, demonstrating manipulation of the direction of an electron beam. Others were focusing of the electrons by an axial magnetic field by Emil Wiechert in 1899,[4] improved oxide-coated cathodes which produced more electrons by Arthur Wehnelt in 1905[5] and the development of the electromagnetic lens in 1926 by Hans Busch.[6] According to Dennis Gabor, the physicist Leó Szilárd tried in 1928 to convince him to build an electron microscope, for which Szilárd had filed a patent.[7]

To this day the issue of who invented the transmission electron microscope is controversial.[8][9][10][11] In 1928, at the Technische Hochschule in Charlottenburg (now Technische Universität Berlin), Adolf Matthias (Professor of High Voltage Technology and Electrical Installations) appointed Max Knoll to lead a team of researchers to advance research on electron beams and cathode-ray oscilloscopes. The team consisted of several PhD students including Ernst Ruska. In 1931, Max Knoll and Ernst Ruska[12][13] successfully generated magnified images of mesh grids placed over an anode aperture. The device, a replicate of which is shown in the figure, used two magnetic lenses to achieve higher magnifications, the first electron microscope. (Max Knoll died in 1969, so did not receive a share of the 1986 Nobel prize for the invention of electron microscopes.)

Apparently independent of this effort was work at Siemens-Schuckert by Reinhold Rüdenberg. According to patent law (U.S. Patent No. 2058914[14] and 2070318,[15] both filed in 1932), he is the inventor of the electron microscope, but it is not clear when he had a working instrument. He stated in a very brief article in 1932[16] that Siemens had been working on this for some years before the patents were filed in 1932, claiming that his effort was parallel to the university development. He died in 1961, so similar to Max Knoll, was not eligible for a share of the 1986 Nobel prize.[17]

In the following year, 1933, Ruska and Knoll built the first electron microscope that exceeded the resolution of an optical (light) microscope.[18] Four years later, in 1937, Siemens financed the work of Ernst Ruska and Bodo von Borries, and employed Helmut Ruska, Ernst's brother, to develop applications for the microscope, especially with biological specimens.[18][19] Also in 1937, Manfred von Ardenne pioneered the scanning electron microscope.[20] Siemens produced the first commercial electron microscope in 1938.[21] The first North American electron microscopes were constructed in the 1930s, at the Washington State University by Anderson and Fitzsimmons [22] and at the University of Toronto by Eli Franklin Burton and students Cecil Hall, James Hillier, and Albert Prebus. Siemens produced a transmission electron microscope (TEM) in 1939.[23] Although current transmission electron microscopes are capable of two million times magnification, as scientific instruments they remain similar but with improved optics.

In the 1940s, high-resolution electron microscopes were developed, enabling greater magnification and resolution.[24] By 1965, Albert Crewe at the University of Chicago introduced the scanning transmission electron microscope using a field emission source,[25] enabling scanning microscopes at high resolution.[26] By the early 1980s improvements in mechanical stability as well as the use of higher accelerating voltages enabled imaging of materials at the atomic scale.[27][28] In the 1980s, the field emission gun became common for electron microscopes, improving the image quality due to the additional coherence and lower chromatic aberrations. The 2000s were marked by advancements in aberration-corrected electron microscopy, allowing for significant improvements in resolution and clarity of images.[29][30]

Types of electron microscopes

[edit]Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

[edit]

The original form of the electron microscope, the transmission electron microscope (TEM), uses a high voltage electron beam to illuminate the specimen and create an image. An electron beam is produced by an electron gun, with the electrons typically having energies in the range 20 to 400 keV, focused by electromagnetic lenses, and transmitted through a thin specimen. When it emerges from the specimen, the electron beam carries information about the structure of the specimen that is then magnified by the lenses of the microscope. The spatial variation in this information (the "image") may be viewed by projecting the magnified electron image onto a detector. For example, the image may be viewed directly by an operator using a fluorescent viewing screen coated with a phosphor or scintillator material such as zinc sulfide. More commonly a high-resolution phosphor is coupled by means of a lens optical system or a fibre optic light-guide to the sensor of a digital camera. A different approach is to use a direct electron detector which has no scintillator, which addresses some of the limitations of scintillator-coupled cameras.[31]

For many years the resolution of TEMs was limited by aberrations of the electron optics, primarily the spherical aberration. In most recent instruments hardware correctors can reduce spherical aberration and other aberrations, improving the resolution in high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) to below 0.5 angstrom (50 picometres),[32] enabling magnifications of more than 50 million times.[33] The ability of HRTEM to determine the positions of atoms within materials is useful for many areas of research and development.[34]

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

[edit]An SEM produces images by probing the specimen with a focused electron beam that is scanned across the specimen (raster scanning). When the electron beam interacts with the specimen, it loses energy and is scattered in different directions by a variety of mechanisms. These interactions lead to, among other events, emission of low-energy secondary electrons and high-energy backscattered electrons, light emission (cathodoluminescence) or X-ray emission. All of these signals carrying information about the specimen, such as the surface topography and composition. The image displayed when using an SEM shows the variation in the intensity of any of these signals as an image. In these each position in the image corresponding to a position of the beam on the specimen when the signal was generated.[35]: 1–15

SEMs are different from TEMs in that they use electrons with much lower energy, generally below 20 keV,[36] while TEMs generally use electrons with energies in the range of 80-300 keV.[37] Thus, the electron sources and optics of the two microscopes have different designs, and they are normally separate instruments.[38]

Scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM)

[edit]A STEM combines features of both a TEM and a SEM by rastering a focused incident probe across a specimen, but now mainly using the electrons which are transmitted through the sample. Many types of imaging are common to both TEM and STEM, but some such as annular dark-field imaging and other analytical techniques are much easier to perform with higher spatial resolutions in a STEM instrument. One drawback is that image data is acquired in serial rather than in parallel fashion.[35]: 75–138

Main operating modes

[edit]

The most common methods of obtaining images in an electron microscope involve selecting different directions for the electrons that have been transmitted through a sample, and/or electrons of different energies. There are a very large number of methods of doing this, although not all are very common.

Secondary electrons

[edit]

In a SEM the signals result from interactions of the electron beam with atoms within the sample. The most common mode is to use the secondary electrons (SE) to produce images. Secondary electrons have very low energies, on the order of 50 eV, which limits their mean free path in solid matter to a few nanometers below the sample surface.[39] The electrons are detected by an Everhart–Thornley detector,[40] which is a type of collector-scintillator-photomultiplier system. The signal from secondary electrons tends to be highly localized at the point of impact of the primary electron beam, making it possible to collect images of the sample surface with a resolution of better than 1 nm, and with specialized instruments at the atomic scale.[41]

The brightness of the signal depends on the number of secondary electrons reaching the detector. If the beam enters the sample perpendicular to the surface, then the electrons come out symmetrically about the axis of the beam. As the angle of incidence increases, the interaction volume from which they cone increases and the "escape" distance from one side of the beam decreases, resulting in more secondary electrons being emitted from the sample. Thus steep surfaces and edges tend to be brighter than flat surfaces, which results in images with a well-defined, three-dimensional appearance that is similar to a reflected light image.[39]

Backscattered electrons

[edit]Backscattered electrons (BSE) are those emitted back out from the specimen due to beam-specimen interactions where the electrons undergo elastic and inelastic scattering. They are conventionally defined as having energies from 50 eV up to the energy of the primary beam. Backscattered electrons can be used for both imaging and to form an electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) image, the latter can be used to determine the crystallography of the specimen.[39]

Heavy elements (high atomic number) backscatter electrons more strongly than light elements (low atomic number), and thus appear brighter in the image, BSE images can therefore be used to detect areas with different chemical compositions.[39] To optimize the signal, dedicated backscattered electron detectors are positioned above the sample in a "doughnut" type arrangement, concentric with the electron beam, maximizing the solid angle of collection. BSE detectors are usually either scintillator or semiconductor types. When all parts of the detector are used to collect electrons symmetrically about the beam, atomic number contrast is produced. However, strong topographic contrast is produced by collecting back-scattered electrons from one side above the specimen using an asymmetrical, directional BSE detector; the resulting contrast appears as if there was illumination of the topography from that side. Semiconductor detectors can be made in radial segments that can be switched in or out to control the type of contrast produced and its directionality.[39]

Diffraction contrast imaging

[edit]Diffraction contrast uses the variation in either or both the direction of diffracted electrons or their amplitude as a function of position as the contrast mechanism. It is one of the simplest ways to image in a transmission electron microscope, and widely used.

The idea is to use an objective aperture below the sample and select only one or a range of different diffracted directions, then use these to form an image. When the aperture includes the incident beam direction the images are called bright field, since in the absence of any sample the field of view would be uniformly bright. When the aperture excludes the incident beam the images are called dark field, since similarly without a sample the image would be uniformly dark.[42][43] One variant of this is called weak-beam dark-field microscopy, and can be used to obtain high resolution images of defects such as dislocations.[44]

High resolution imaging

[edit]

In high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (also sometimes called high-resolution electron microscopy) a number of different diffracted beams are allowed through the objective aperture. These interfere, leading to images which represent the atomic structure of the material. These can include the incident beam direction, or with scanning transmission electron microscopes they typically are for a range of diffracted beams excluding the incident beam.[28] Depending upon how thick the samples are and the aberrations of the microscope, these images can either be directly interpreted in terms of the positions of columns of atoms, or require a more careful analysis using calculations of the multiple scattering of the electrons[45] and the effect of the contrast transfer function of the microscope.[46]

There are many other imaging variants that can also to lead to atomic level information. Electron holography uses the interference of electrons which have been through the sample and a reference beam.[47] 4D STEM collects diffraction data at each point using a scanning instrument, then processes them to produce different types of images.[48]

X-ray microanalysis

[edit]

X-ray microanalysis is a method of obtaining local chemical information within electron microscopes of all types, although it is most commonly used in scanning instruments. When high energy electrons interact with atoms they can knock out electrons, particularly those in the inner shells and core electrons. These are then filled by valence electron, and the energy difference between the valence and core states can be converted into an x-ray which is detected by a spectrometer. The energies of these x-rays is somewhat specific to the atomic species, so local chemistry can be probed.[39]

EELS

[edit]

Similar to X-ray microanalysis, the energies of electrons which have transmitted through a sample can be analyzed and yield information ranging from details of the local electronic structure to chemical information.[50]

Electron diffraction

[edit]Transmission electron microscopes can be used in electron diffraction mode where a map of the angles of the electrons leaving the sample is produced. The advantages of electron diffraction over X-ray crystallography are primarily in the size of the crystals. In X-ray crystallography, crystals are commonly visible by the naked eye and are generally in the hundreds of micrometers in length. In comparison, crystals for electron diffraction must be less than a few hundred nanometers in thickness, and have no lower boundary of size. Additionally, electron diffraction is done on a TEM, which can also be used to obtain other types of information, rather than requiring a separate instrument.[51][37]

There are many variants on electron diffraction, depending upon exactly what type of illumination conditions are used. If a parallel beam is used with an aperture to limit the region exposed to the electrons then sharp diffraction features are normally observed, a technique called selected area electron diffraction. This is often the main technique used. Another common approach uses conical illumination and is called convergent beam electron diffraction (CBED). This is good for determining the symmetry of materials. A third is precession electron diffraction, where a parallel beam is spun around a large angle, producing a type of average diffraction pattern.[52] These often have less multiple scattering.[53]

Other electron microscope techniques

[edit]- Cathodoluminescence - analysing photons due to the electron beam

- Charge contrast imaging - using how charging varies with position to produce images

- CryoEM - using frozen samples, almost always biological samples

- EBSD - using the back-scattered electrons, typically in a SEM

- TKD - using the Kikuchi lines in diffraction patterns

- ECCI - using contrast due to electron channelling

- EBIC - measuring the current produced as a function of the position of a small beam

- Electron tomography - methods to produce 3D information by combining images

- FEM - technique to interrogate nanocrystalline materials

- Immune electron microscopy - the use of electron microscopy in immunology

- Geometric phase analysis - a method to analyze high-resolution images

- Serial block-face scanning electron microscopy - a way to produce 3D information from many images

- WDXS - higher precision detection of x-rays to analyze local chemistry

Aberration corrected instruments

[edit]

Aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy (AC-TEM) is the general term for electron microscopes where electro optical components are introduced to reduce the aberrations that would otherwise limit the resolution of the images. Historically electron microscopes had quite severe aberrations, and until about the start of the 21st century the resolution was limited, able to image the atomic structure of materials if the atoms were far enough apart.[54] Around the turn of the century the electron optical components were coupled with computer control of the lenses and their alignment, enabling correction of aberrations. The first demonstration of aberration correction in TEM mode was by Harald Rose and Maximilian Haider in 1998 using a hexapole corrector, and in STEM mode by Ondrej Krivanek and Niklas Dellby in 1999 using a quadrupole/octupole corrector.[55]

As of 2025 correction of geometric aberrations is standard in many commercial electron microscopes, and they are extensively used in many different areas of science.[56][57] Similar correctors have also been used at much lower energies for LEEM instruments.[58]

Sample preparation

[edit]

Samples for electron microscopes mostly cannot be observed directly. The samples need to be prepared to stabilize the sample and enhance contrast. Preparation techniques differ vastly in respect to the sample and its specific qualities to be observed as well as the specific microscope used. Details can be found in the relevant main articles listed above.

Disadvantages

[edit]

Electron microscopes are expensive to build and maintain. Microscopes designed to achieve high resolutions must be housed in stable buildings (sometimes underground) with special services such as magnetic field canceling systems and anti vibration mounts.[59]

The samples largely have to be viewed in vacuum, as the molecules that make up air would scatter the electrons. An exception is liquid-phase electron microscopy[60] using either a closed liquid cell or an environmental chamber, for example, in the environmental scanning electron microscope, which allows hydrated samples to be viewed in a low-pressure (up to 20 Torr or 2.7 kPa) wet environment. Various techniques for in situ electron microscopy of gaseous samples have also been developed.[61]

Samples of hydrated materials, including almost all biological specimens, have to be prepared in various ways to stabilize them, reduce their thickness (ultrathin sectioning) and increase their electron optical contrast (staining). These processes may result in artifacts, but these can usually be identified by comparing the results obtained by using radically different specimen preparation methods. Since the 1980s, analysis of cryofixed, vitrified specimens has also become increasingly used.[63][64][65]

Many samples suffer from radiation damage which can change internal structures. This can be due to either or both radiolytic processes or ballistic, for instance with collision cascades.[66] This can be a severe issue for biological samples,[67][68]

See also

[edit]- List of materials analysis methods

- Electron diffraction

- Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS)

- Electron microscope images

- Energy filtered transmission electron microscopy (EFTEM)

- Environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM)

- Immune electron microscopy

- In situ electron microscopy

- Low-energy electron microscopy

- Microscope image processing

- Microscopy

- Scanning confocal electron microscopy

- Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

- Thin section

- Transmission Electron Aberration-Corrected Microscope

- Volumetric Electron Microscopy

References

[edit]- ^ "Electron microscope". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ Calbick CJ (1944). "Historical Background of Electron Optics". Journal of Applied Physics. 15 (10): 685–690. Bibcode:1944JAP....15..685C. doi:10.1063/1.1707371.

- ^ Hertz H (2019). "Introduction to Heinrich Hertz's Miscellaneous Papers (1895) by Philipp Lenard". In Mulligan JF (ed.). Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (1857-1894) : a collection of articles and addresses. Routledge. pp. 87–88. doi:10.4324/9780429198960-4. ISBN 978-0-429-19896-0.

- ^ Wiechert E (1899). "Experimentelle Untersuchungen über die Geschwindigkeit und die magnetische Ablenkbarkeit der Kathodenstrahlen" [Experimental Investigations on the Velocity and Magnetic Deflection of Cathode Rays]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie (in German). 305 (12): 739–766. Bibcode:1899AnP...305..739W. doi:10.1002/andp.18993051203.

- ^ Wehnelt A (1905). "X. On the discharge of negative ions by glowing metallic oxides, and allied phenomena". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 10 (55): 80–90. doi:10.1080/14786440509463347.

- ^ Busch H (1926). "Berechnung der Bahn von Kathodenstrahlen im axialsymmetrischen elektromagnetischen Felde" [Calculation of the trajectory of cathode rays in an axially symmetric electromagnetic field]. Annalen der Physik (in German). 386 (25): 974–993. Bibcode:1926AnP...386..974B. doi:10.1002/andp.19263862507.

- ^ Dannen, Gene (1998) Leo Szilard the Inventor: A Slideshow (1998, Budapest, conference talk). dannen.com

- ^ Mulvey T (1962). "Origins and historical development of the electron microscope". British Journal of Applied Physics. 13 (5): 197–207. doi:10.1088/0508-3443/13/5/303.

- ^ Tao Y (2018). "A Historical Investigation of the Debates on the Invention and Invention Rights of Electron Microscope". Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2018). Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. Atlantis Press. pp. 1438–1441. doi:10.2991/iccessh-18.2018.313. ISBN 978-94-6252-528-3.

- ^ Freundlich MM (October 1963). "Origin of the Electron Microscope". Science. 142 (3589): 185–188. Bibcode:1963Sci...142..185F. doi:10.1126/science.142.3589.185. PMID 14057363.

- ^ Rüdenberg R (2010). Origin and Background of the Invention of the Electron Microscope. Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics. Vol. 160. pp. 171–205. doi:10.1016/s1076-5670(10)60005-5. ISBN 978-0-12-381017-5..

- ^ Knoll M, Ruska E (1932). "Beitrag zur geometrischen Elektronenoptik. I". Annalen der Physik. 404 (5): 607–640. Bibcode:1932AnP...404..607K. doi:10.1002/andp.19324040506.

- ^ Knoll M, Ruska E (1932). "Das Elektronenmikroskop". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). 78 (5–6): 318–339. Bibcode:1932ZPhy...78..318K. doi:10.1007/BF01342199.

- ^ Rüdenberg R. "Apparatus for producing images of objects". Patent Public Search Basic. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Rüdenberg R. "Apparatus for producing images of objects". Patent Public Search Basic. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Rüdenberg R (July 1932). "Elektronenmikroskop". Die Naturwissenschaften. 20 (28): 522. Bibcode:1932NW.....20..522R. doi:10.1007/BF01505383.

- ^ "History of Electron Microscope". LEO Electron Microscopy. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Ruska, Ernst (1986). "Ernst Ruska Autobiography". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ Kruger DH, Schneck P, Gelderblom HR (May 2000). "Helmut Ruska and the visualisation of viruses". Lancet. 355 (9216): 1713–1717. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02250-9. PMID 10905259.

- ^ Von Ardenne M, Beischer D (1940). "Untersuchung von Metalloxyd-Rauchen mit dem Universal-Elektronenmikroskop" [Investigation of metal oxide smoking with the universal electron microscope]. Zeitschrift für Elektrochemie und Angewandte Physikalische Chemie (in German). 46 (4): 270–277. doi:10.1002/bbpc.19400460406.

- ^ History of electron microscopy, 1931–2000. Authors.library.caltech.edu (2002-12-10). Retrieved on 2017-04-29.

- ^ "North America's first electron microscope".

- ^ "James Hillier". Inventor of the Week: Archive. 2003-05-01. Archived from the original on 2003-08-23. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ Hawkes PW (2021). The Beginnings of Electron Microscopy. Part 1. London San Diego, CA Cambridge, MA Oxford: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-323-91507-6.

- ^ Crewe AV, Eggenberger DN, Wall J, Welter LM (1968-04-01). "Electron Gun Using a Field Emission Source". Review of Scientific Instruments. 39 (4): 576–583. Bibcode:1968RScI...39..576C. doi:10.1063/1.1683435.

- ^ Crewe AV (November 1966). "Scanning electron microscopes: is high resolution possible?". Science. 154 (3750): 729–738. Bibcode:1966Sci...154..729C. doi:10.1126/science.154.3750.729. PMID 17745977.

- ^ Smith DJ, Camps RA, Freeman LA, Hill R, Nixon WC, Smith KC (May 1983). "Recent improvements to the Cambridge University 600 kV High Resolution Electron Microscope". Journal of Microscopy. 130 (2): 127–136. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2818.1983.tb04211.x.

- ^ a b Spence JC (2013). High-Resolution Electron Microscopy. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668632.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-966863-2.[page needed]

- ^ Hawkes PW (28 September 2009). "Aberration correction past and present". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 367 (1903): 3637–3664. Bibcode:2009RSPTA.367.3637H. doi:10.1098/rsta.2009.0004. PMID 19687058.

- ^ Rose HH (June 2009). "Historical aspects of aberration correction". Journal of Electron Microscopy. 58 (3): 77–85. doi:10.1093/jmicro/dfp012. PMID 19254915.

- ^ Cheng Y, Grigorieff N, Penczek PA, Walz T (April 2015). "A primer to single-particle cryo-electron microscopy". Cell. 161 (3): 438–449. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.050. PMC 4409659. PMID 25910204.

- ^ Erni R, Rossell MD, Kisielowski C, Dahmen U (March 2009). "Atomic-resolution imaging with a sub-50-pm electron probe". Physical Review Letters. 102 (9) 096101. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102i6101E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.096101. OSTI 960283. PMID 19392535.

- ^ "The Scale of Things". Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy. 2006-05-26. Archived from the original on 2010-02-01. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ O'Keefe MA, Allard LF (2004-01-18). "Sub-Ångstrom Electron Microscopy for Sub-Ångstrom Nano-Metrology" (PDF). Information Bridge: DOE Scientific and Technical Information – Sponsored by OSTI.

- ^ a b Kohl H, Reimer L (2008). "Elements of a Transmission Electron Microscope". Transmission Electron Microscopy. Springer Series in Optical Sciences. Vol. 36. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-40093-8_4. ISBN 978-0-387-40093-8.

- ^ Dusevich V, Purk J, Eick J (January 2010). "Choosing the Right Accelerating Voltage for SEM (An Introduction for Beginners)". Microscopy Today. 18 (1): 48–52. doi:10.1017/s1551929510991190.

- ^ a b Saha A, Nia SS, Rodríguez JA (September 2022). "Electron Diffraction of 3D Molecular Crystals". Chemical Reviews. 122 (17): 13883–13914. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00879. PMC 9479085. PMID 35970513.

- ^ "Electron Microscopy | Thermo Fisher Scientific - US". 2022-04-07. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2024-07-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Goldstein J (2003-01-31). Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis: Third Edition. Springer US. ISBN 978-0-306-47292-3.

- ^ Everhart TE, Thornley, R. F. M. (1960). "Wide-band detector for micro-microampere low-energy electron currents" (PDF). Journal of Scientific Instruments. 37 (7): 246–248. Bibcode:1960JScI...37..246E. doi:10.1088/0950-7671/37/7/307.

- ^ Ciston J, Brown HG, D'Alfonso AJ, Koirala P, Ophus C, Lin Y, et al. (2015-06-17). "Surface determination through atomically resolved secondary-electron imaging". Nature Communications. 6 (1) 7358. doi:10.1038/ncomms8358. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4557350. PMID 26082275.

- ^ Hirsch PB, Howie A, Nicholson RB, Pashley DW, Whelan MJ (1965). Electron microscopy of thin crystals. London: Butterworths. ISBN 0-408-18550-3. OCLC 2365578.

- ^ Reimer L (1997). "Transmission Electron Microscopy". Springer Series in Optical Sciences. 36. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-14824-2. ISBN 978-3-662-14826-6. ISSN 0342-4111.

- ^ Cockayne DJ, Ray IL, Whelan MJ (1969-12-01). "Investigations of dislocation strain fields using weak beams". The Philosophical Magazine. 20 (168): 1265–1270. Bibcode:1969PMag...20.1265C. doi:10.1080/14786436908228210. ISSN 0031-8086.

- ^ Ishizuka K (2004-02-01). "FFT Multislice Method—The Silver Anniversary". Microscopy and Microanalysis. 10 (1): 34–40. doi:10.1017/S1431927604040292. ISSN 1431-9276.

- ^ Wade RH (1992-10-01). "A brief look at imaging and contrast transfer". Ultramicroscopy. 46 (1): 145–156. doi:10.1016/0304-3991(92)90011-8. ISSN 0304-3991.

- ^ Cowley JM (1992-06-01). "Twenty forms of electron holography". Ultramicroscopy. 41 (4): 335–348. doi:10.1016/0304-3991(92)90213-4. ISSN 0304-3991.

- ^ Ophus C (2019-06-01). "Four-Dimensional Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (4D-STEM): From Scanning Nanodiffraction to Ptychography and Beyond". Microscopy and Microanalysis. 25 (3): 563–582. doi:10.1017/S1431927619000497. ISSN 1431-9276.

- ^ Corbari, L, et al. (2008). "Iron oxide deposits associated with the ectosymbiotic bacteria in the hydrothermal vent shrimp Rimicaris exoculata". Biogeosciences. 5 (5): 1295–1310. Bibcode:2008BGeo....5.1295C. doi:10.5194/bg-5-1295-2008.

- ^ Egerton RF (1986), "An Introduction to Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy", Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 1–25, doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-6887-2_1, ISBN 978-1-4615-6889-6, retrieved 2025-02-25

- ^ Cowley JM (1995). Diffraction physics. North Holland personal library (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-82218-5.

- ^ Vincent R, Midgley P (1994). "Double conical beam-rocking system for measurement of integrated electron diffraction intensities". Ultramicroscopy. 53 (3): 271–82. doi:10.1016/0304-3991(94)90039-6.

- ^ Own, C. S.: PhD thesis, System Design and Verification of the Precession Electron Diffraction Technique, Northwestern University, 2005,http://www.numis.northwestern.edu/Research/Current/precession.shtml

- ^ Smith DJ (1997-12-01). "The realization of atomic resolution with the electron microscope". Reports on Progress in Physics. 60 (12): 1513–1580. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/60/12/002. ISSN 0034-4885.

- ^ Pennycook SJ (2012-12-01). "Seeing the atoms more clearly: STEM imaging from the Crewe era to today". Ultramicroscopy. Albert Victor Crewe Memorial Issue. 123: 28–37. doi:10.1016/j.ultramic.2012.05.005. ISSN 0304-3991. PMID 22727567.

- ^ Erni R (2015-03-23). Aberration-corrected Imaging In Transmission Electron Microscopy: An Introduction (2nd ed.). World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-78326-530-5.

- ^ Rose H (2006-07-01). "Aberration correction in electron microscopy". International Journal of Materials Research. 97 (7): 885–889. doi:10.1515/ijmr-2006-0143. ISSN 2195-8556.

- ^ Tromp R, Hannon J, Ellis A, Wan W, Berghaus A, Schaff O (June 2010). "A new aberration-corrected, energy-filtered LEEM/PEEM instrument. I. Principles and design". Ultramicroscopy. 110 (7): 852–861. doi:10.1016/j.ultramic.2010.03.005. PMID 20395048.

- ^ Song YL, Lin HY, Manikandan S, Chang LM (March 2022). "A Magnetic Field Canceling System Design for Diminishing Electromagnetic Interference to Avoid Environmental Hazard". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (6): 3664. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063664. PMC 8954143. PMID 35329350.

- ^ Williamson MJ, Tromp RM, Vereecken PM, Hull R, Ross FM (August 2003). "Dynamic microscopy of nanoscale cluster growth at the solid-liquid interface". Nature Materials. 2 (8): 532–536. Bibcode:2003NatMa...2..532W. doi:10.1038/nmat944. PMID 12872162.

- ^ Gai PL, Boyes ED (March 2009). "Advances in atomic resolution in situ environmental transmission electron microscopy and 1A aberration corrected in situ electron microscopy". Microscopy Research and Technique. 72 (3): 153–164. arXiv:1705.05754. doi:10.1002/jemt.20668. PMID 19140163.

- ^ Demina TA, Oksanen HM (2020-11-01). "Pleomorphic archaeal viruses: the family Pleolipoviridae is expanding by seven new species". Archives of Virology. 165 (11): 2723–2731. doi:10.1007/s00705-020-04689-1. ISSN 1432-8798. PMC 7547991. PMID 32583077.

- ^ Adrian M, Dubochet J, Lepault J, McDowall AW (1984). "Cryo-electron microscopy of viruses" (PDF). Nature (Submitted manuscript). 308 (5954): 32–36. Bibcode:1984Natur.308...32A. doi:10.1038/308032a0. PMID 6322001.

- ^ Sabanay I, Arad T, Weiner S, Geiger B (September 1991). "Study of vitrified, unstained frozen tissue sections by cryoimmunoelectron microscopy". Journal of Cell Science. 100 (1): 227–236. doi:10.1242/jcs.100.1.227. PMID 1795028.

- ^ Kasas S, Dumas G, Dietler G, Catsicas S, Adrian M (July 2003). "Vitrification of cryoelectron microscopy specimens revealed by high-speed photographic imaging". Journal of Microscopy. 211 (Pt 1): 48–53. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2818.2003.01193.x. PMID 12839550.

- ^ Egerton RF, Li P, Malac M (2004-08-01). "Radiation damage in the TEM and SEM". Micron. International Wuhan Symposium on Advanced Electron Microscopy. 35 (6): 399–409. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2004.02.003. ISSN 0968-4328.

- ^ Glaeser RM (1971-08-01). "Limitations to significant information in biological electron microscopy as a result of radiation damage". Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 36 (3): 466–482. doi:10.1016/S0022-5320(71)80118-1. ISSN 0022-5320.

- ^ Baker LA, Rubinstein JL (2010-01-01), Jensen GJ (ed.), "Chapter Fifteen - Radiation Damage in Electron Cryomicroscopy", Methods in Enzymology, Cryo-EM Part A Sample Preparation and Data Collection, vol. 481, Academic Press, pp. 371–388, doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(10)81015-8, retrieved 2025-05-15

External links

[edit]- An Introduction to Microscopy Archived 2013-07-19 at the Wayback Machine: resources for teachers and students

- Cell Centered Database – Electron microscopy data

- Science Aid: Electron Microscopy:By Kaden park

Electron microscope

View on GrokipediaPrinciples of operation

Electron optics and wave nature

The wave nature of electrons, first proposed by Louis de Broglie in 1924, enables their use in microscopy by associating a wavelength with particles based on their momentum. The de Broglie wavelength is given by the formula , where is Planck's constant and is the electron's momentum.[4] For accelerated electrons, this wavelength is inversely proportional to their velocity, allowing high-energy electrons (typically 100–300 keV in microscopes) to achieve de Broglie wavelengths on the order of picometers, such as approximately 3.88 pm at 100 keV.[5] This is orders of magnitude shorter than visible light wavelengths (around 400–700 nm), which limits light microscopy resolution to about 200 nm, whereas electrons enable sub-angstrom (less than 0.1 nm) imaging potential.[5][6] In electron microscopy, the interaction of the electron beam with matter primarily involves scattering events that form the basis for image contrast. Elastic scattering occurs when an electron is deflected without significant energy loss, preserving its kinetic energy while changing direction, often through Coulomb interactions with atomic nuclei; high-angle elastic events are described by Rutherford scattering, where the differential cross-section is proportional to and is the scattering angle.[7] In contrast, inelastic scattering involves energy transfer to the sample, such as exciting inner-shell electrons or phonons, leading to energy losses of a few electron volts to thousands, which can generate signals like X-rays or secondary electrons but also broadens the beam.[8] These interactions, dominated by elastic scattering for imaging due to its role in phase shifts and diffraction, allow electrons to probe atomic-scale structures far beyond light-based methods. Electron optics relies on magnetic fields to manipulate the beam, analogous to glass lenses in light microscopy but exploiting the charged nature of electrons. The focusing principle stems from the Lorentz force, , where is the electron charge, is its velocity, and is the magnetic field; in a solenoid or magnetic lens, the azimuthal field component causes off-axis electrons to spiral inward, converging the beam at a focal point. Electromagnetic lenses, combining static magnetic fields with variable currents, enable adjustable focal lengths and beam control, forming images through successive focusing stages. However, imperfections in these fields introduce aberrations that degrade image quality. Spherical aberration in electron optics arises from the lens's inability to focus rays parallel to the optic axis at the same point, with peripheral rays focusing closer than paraxial ones due to stronger field gradients at larger radii, resulting in a blurred disk of confusion proportional to the third power of the aperture angle.[9] Chromatic aberration occurs because electrons with slightly different energies (from beam energy spread or scattering) experience varying refractive indices in the magnetic field, causing lower-energy electrons to focus shorter than higher-energy ones and further limiting resolution.[9] These aberrations, inherent to static round lenses as proven by Scherzer's theorem in 1936, restrict practical resolutions despite the short de Broglie wavelength, though they can be mitigated in principle by optimizing lens design without altering the fundamental wave properties.[10]Resolution limits and magnification

The resolution in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is fundamentally governed by the Abbe diffraction limit, adapted for electron optics as , where is the minimum resolvable distance, is the de Broglie wavelength of the electrons, and is the semi-angle of the objective aperture.[11] This formula highlights how shorter electron wavelengths—on the order of picometers at typical accelerating voltages—combined with optimized aperture angles, enable resolutions far superior to light microscopy. However, practical implementation requires careful control of optical parameters to approach this theoretical bound. Magnification in electron microscopes is defined as the ratio of the image size to the object size, image size / object size, and serves to enlarge features for visualization. In TEM, practical magnification limits reach up to 50 million times, allowing detailed examination of atomic-scale structures, though higher values are often limited by specimen stability and detector capabilities rather than optical constraints.[12] Several factors impose practical limits on resolution beyond the diffraction barrier, including lens aberrations such as spherical and chromatic effects, which distort the electron beam focus; beam divergence, which reduces coherence; and stability requirements for voltage, current, and mechanical vibrations that prevent drift during imaging.[6] These elements collectively degrade image contrast and sharpness, necessitating precise instrumentation to mitigate their impact. A key distinction exists between point resolution and the information limit in electron microscopy. Point resolution refers to the smallest distance at which two points can be distinguished under ideal coherent illumination, primarily limited by spherical aberration in uncorrected systems. In contrast, the information limit accounts for partial coherence effects from chromatic aberration and energy spread in the electron source, which dampen high-frequency information transfer through an envelope function, effectively reducing resolvable details. Modern aberration-corrected instruments achieve effective resolutions around 0.05 nm by pushing this information limit, enabling atomic-scale imaging in materials science applications.[13][14] Across electron microscope types, resolution varies significantly: TEM and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) routinely attain sub-nanometer levels, often below 0.1 nm with corrections, while scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is typically limited to approximately 1 nm due to its surface-scanning nature and larger probe sizes.[15]History

Early development and invention

The discovery of the electron by J. J. Thomson in 1897 marked a pivotal moment in physics, as his experiments with cathode rays demonstrated that these rays consisted of negatively charged particles far smaller and lighter than atoms, which he termed "corpuscles" (later renamed electrons). This identification of the electron as a discrete particle provided the essential building block for subsequent technologies involving electron beams.[16] Building on this, Louis de Broglie proposed in 1924 that all matter, including electrons, exhibits wave-particle duality, hypothesizing that particles possess an associated wavelength inversely proportional to their momentum.[17] This revolutionary idea extended quantum concepts from light to matter, suggesting that electrons could be manipulated like waves for imaging purposes. The wave nature of electrons was experimentally verified in 1927 through the Davisson-Germer experiment, conducted at Bell Laboratories, where electrons diffracted off a nickel crystal lattice produced interference patterns consistent with de Broglie's predicted wavelength of approximately 0.165 nm for 54 eV electrons. This confirmation established electrons as suitable for high-resolution optics, far surpassing the wavelength limitations of visible light (around 500 nm).[18] These foundational concepts—electrons as particles with wave properties—directly inspired the development of electron microscopy in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In 1931, Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll at the Technical University of Berlin constructed the first prototype transmission electron microscope, using magnetic coils as lenses to focus an electron beam and achieve a magnification of 400× on a test grid, exceeding the resolution of contemporary light microscopes. This device demonstrated the feasibility of electron-optical imaging but suffered from beam instability and low contrast. Independently, in May 1931, Reinhold Rüdenberg at Siemens-Schuckertwerke filed a patent for an electron microscope design using electrostatic lenses (German patent application, leading to US Patent 2,058,914 in 1936).[19] By 1933, Ruska refined the prototype with improved magnetic lenses, attaining a magnification of 12,000× and enabling clearer imaging of fine structures, such as etched platinum sheets.[20] A key innovation came in 1932 when Ruska, in collaboration with Bodo von Borries, patented a short-focal-length magnetic polepiece lens (German Patent No. 680284), which minimized aberrations and allowed precise electron beam control essential for practical microscopy. This design became the basis for all subsequent magnetic electron microscopes.[20] These advancements culminated in 1939 with Siemens & Halske producing the first commercial transmission electron microscope, the Super Microscope, capable of 20,000× magnification and resolutions down to 10 nm, marking the transition from laboratory prototypes to industrial tools.[21] Parallel efforts in the United States during the 1930s, including early electron optics research at institutions like MIT, yielded prototypes such as the 1938 transmission electron microscope built at the University of Toronto (the first successful one in North America), but these initial designs achieved only limited resolution and stability compared to German innovations.[22]Key advancements and commercialization

During World War II, the United States emerged as a leader in electron microscopy development, driven by the need for advanced materials analysis in military applications. Vladimir Zworykin, leading a team at the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), oversaw the creation of improved transmission electron microscopes (TEMs) in the early 1940s, including a more affordable model demonstrated in 1942 that enabled broader wartime deployment for studying alloys and other materials.[23][24] The invention of the scanning electron microscope (SEM) built on early prototypes from the 1930s. In 1935, Max Knoll constructed the first SEM prototype, demonstrating basic scanning principles for surface imaging. Two years later, in 1937, Manfred von Ardenne advanced the design with a scanning transmission system using a finely focused electron probe, laying foundational concepts for high-resolution surface examination. Commercialization followed postwar, with practical prototypes developed in the early 1950s by Charles Oatley and his team at the University of Cambridge, culminating in the first commercial SEM, the Stereoscan, released by the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company in 1965, which facilitated industrial adoption for materials characterization.[25][26] Further innovations in the 1960s expanded electron microscopy capabilities. In 1966, Albert Crewe at the University of Chicago developed the scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) with an annular dark-field detector, enabling atomic-scale imaging by collecting scattered electrons from a focused probe, which improved contrast for heavy atoms in biological and materials samples.[27][28] Commercialization accelerated in the mid-20th century, particularly through Japanese manufacturers. Hitachi began producing electron microscopes in the 1940s and entered the international market in the 1950s with reliable TEM models, while Japan Electron Optics Laboratory (JEOL), founded in 1949, started manufacturing magnetic TEMs in 1950 and expanded globally by the mid-1950s, making high-vacuum instruments more accessible for research and industry. By the 1970s, advancements in lens design and electron sources pushed TEM resolution to 0.2 nm, as exemplified by JEOL's JEM-100B model introduced in 1968, which supported detailed crystallographic studies.[29][30][31] The field's impact was recognized in 1986 when Ernst Ruska received the Nobel Prize in Physics for his foundational work in electron optics and the design of the first electron microscope, highlighting its transformative role in scientific imaging up to that point.[32]Types of electron microscopes

Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

The transmission electron microscope (TEM) is configured such that a beam of accelerated electrons passes through an ultra-thin specimen, generally less than 100 nm in thickness, to produce an image from the electrons transmitted through the sample.[33] This electron-transparent preparation allows for the visualization of internal structures at the nanoscale, with the beam interacting via scattering and absorption to generate contrast.[34] The setup relies on electromagnetic lenses to focus the beam, similar to general electron optics principles.[33] In TEM imaging, two primary modes are employed: bright-field and dark-field. Bright-field imaging collects the direct, unscattered transmitted electrons, resulting in areas of higher mass-thickness appearing darker due to increased scattering.[34] Conversely, dark-field imaging utilizes scattered electrons, often those diffracted at specific angles, to highlight crystalline features and defects by blocking the direct beam.[33] TEM finds extensive applications in revealing biological ultrastructures, such as the morphology of viruses including polyomaviruses and coronaviruses, enabling direct visualization and diagnosis in clinical samples.[35] In materials science, it is used to examine defects like dislocations in metallic nanostructures and carbon-based materials, providing insights into phase evolution and atomic arrangements.[36] These capabilities support fields from virology to nanomaterial engineering.[37] TEM instruments achieve magnifications ranging from 10× to 1,000,000×, with resolutions approaching 0.1 nm in aberration-corrected systems, allowing atomic-scale imaging.[34] Historically, the first practical applications of TEM in metallurgy occurred in the 1940s, when Robert Heidenreich at Bell Labs used electrolytic thinning to study metal crystal textures in 1949.[28]Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) operates by directing a finely focused beam of electrons across the surface of a sample in a raster-scanning pattern, point by point, to generate images based on the emitted signals from electron-sample interactions.[38] This sequential scanning allows for the construction of detailed topographic maps of the specimen's surface, with the intensity of detected signals determining the brightness of each pixel in the resulting image.[39] SEM accommodates bulk samples up to several centimeters in scale, unlike transmission-based methods that require ultrathin sections, enabling the examination of three-dimensional objects without extensive dissection.[40] For biological samples, standard SEM requires chemical fixation to preserve structure (which kills the cells), followed by dehydration, critical point drying, and coating with a conductive material such as gold or carbon to mitigate charging effects in the high vacuum environment.[41] Additionally, environmental SEM variants operate at lower vacuum levels, facilitating imaging of hydrated or uncoated specimens such as biological materials—including wet cells or bacteria—allowing observation of dynamic surface processes without drying or coating, though long-term cell viability may be limited by the reduced vacuum and electron beam exposure.[42] The SEM's depth of field is approximately 300 times greater than that of optical microscopes, owing to the small interaction volume of the electron beam with the sample surface, which allows sharp focus across a wide range of heights in the specimen.[43] Typical SEM resolution ranges from 0.5 to 10 nm, depending on beam energy, probe current, and sample preparation, while magnification can reach up to 1,000,000× for high-detail surface features.[39][44] These capabilities arise from the short de Broglie wavelength of electrons and precise beam control, enabling visualization of nanoscale surface structures.[39] Emitted signals, such as secondary electrons for topography and backscattered electrons for compositional contrast, are detected to form the image.[38] SEM finds widespread applications in analyzing fracture surfaces to identify failure mechanisms in materials, such as crack propagation paths in metals or composites.[45] In biology, it reveals intricate surface details on specimens like insect exoskeletons or cellular membranes after appropriate coating.[46] Forensic investigations employ SEM to examine trace evidence, including gunshot residue particles or fiber morphologies for evidentiary matching.[47]Scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM)

The scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) is a versatile instrument that integrates the scanning probe approach with transmission electron microscopy principles, enabling high-resolution imaging of thin specimens at the atomic scale. In STEM, a finely focused electron beam is raster-scanned across the sample, allowing for the collection of transmitted electrons to form images that reveal internal structure and composition with exceptional detail. This hybrid design facilitates simultaneous acquisition of multiple signal types, making it particularly suited for analytical studies in materials science.[48] The basic setup of a STEM involves a high-brightness electron source, such as a field emission gun, which generates a probe beam converged to a sub-angstrom diameter and scanned over the specimen using deflection coils. The thin sample, typically less than 100 nm thick, is positioned such that electrons transmit through it, interacting via elastic and inelastic scattering processes. Multiple detectors are arranged below the sample to capture these transmitted electrons at various angles: a bright-field detector collects unscattered or low-angle scattered beams for phase-contrast information, while segmented or annular detectors record higher-angle scattering for amplitude-contrast details. This configuration allows for real-time imaging and simultaneous data collection from diverse signals, enhancing the efficiency of nanoscale characterization.[48][49] The development of STEM traces back to the pioneering efforts of Albert Crewe and his team at the University of Chicago in the late 1960s and 1970s, who constructed the first practical instrument capable of atomic-resolution imaging using a field-emission source and annular detectors. Crewe's innovations, including the demonstration of single-atom visibility in 1970, laid the foundation for modern STEM by emphasizing Z-contrast imaging over conventional bright-field modes. By the 1980s, commercial STEM systems emerged, and with the advent of aberration correction in the 2000s, STEM became a standard tool in analytical electron microscopy for its ability to combine high spatial resolution with spectroscopic capabilities. Today, STEM instruments are integral to advanced laboratories worldwide, supporting multidisciplinary research from condensed matter physics to nanotechnology.[50][51] A key imaging mode in STEM is annular dark-field (ADF) imaging, which employs a ring-shaped detector to collect high-angle scattered electrons, producing Z-contrast images where intensity scales with the square of the atomic number (Z²) due to incoherent Rutherford scattering. This sensitivity to atomic number enables clear visualization of heavy elements against lighter backgrounds without the phase contrast artifacts common in bright-field TEM, making ADF-STEM ideal for locating impurities or mapping elemental distributions in complex alloys. The contrast arises primarily from thermal diffuse scattering at elevated angles, minimizing contributions from crystalline diffraction and providing chemically intuitive images.[52][53] STEM finds extensive applications in atomic-scale materials analysis, particularly for studying catalyst nanoparticles where it reveals active site distributions and structural dynamics under operational conditions. For instance, in situ STEM observations of platinum-based catalysts during reactions provide insights into particle sintering and facet evolution, aiding the design of more efficient heterogeneous catalysts. Another prominent application is 4D-STEM, which records a full diffraction pattern at each scan position to enable strain mapping, quantifying lattice distortions in semiconductors or 2D materials with nanometer precision. This technique has been instrumental in analyzing strain fields around defects in graphene heterostructures, informing device performance optimization.[48][54][55] With aberration correction, STEM achieves sub-0.05 nm resolution, allowing direct imaging of atomic columns and even light elements like oxygen in oxides. This breakthrough, realized in instruments like the TEAM 0.5 project microscope in 2007, extends the probe size limit from ~0.1 nm to below 50 pm, enabling quantitative analysis of beam-sensitive materials without significant damage. Such resolutions have revolutionized fields like quantum materials research by permitting the observation of subtle bonding arrangements and electronic inhomogeneities.[56]Instrumentation and components

Electron sources

Electron sources in electron microscopes generate beams of electrons that are accelerated and focused to illuminate specimens, with the source type determining key beam properties such as brightness, coherence, and stability.[58] The primary types include thermionic emission guns and field emission guns (FEGs), each suited to different imaging demands based on their emission mechanisms and performance characteristics.[59] Thermionic guns, the most common for standard applications, rely on heating a cathode filament to emit electrons via thermal excitation. Typically, these use a tungsten hairpin filament heated to approximately 2700 K, producing a beam with moderate brightness of about 10^5 A/cm² sr.[59] This design is robust and cost-effective, making it widely adopted in conventional transmission electron microscopes (TEMs) and scanning electron microscopes (SEMs) where ultra-high resolution is not required.[60] However, the larger source size (crossover diameter around 50 μm) limits beam coherence compared to advanced sources.[61] Field emission guns (FEGs) offer superior performance for high-resolution imaging by extracting electrons through quantum tunneling under a strong electric field applied to a sharply pointed cathode. These include cold field emission guns, operating at room temperature, and Schottky (thermal-assisted) FEGs, which heat the emitter slightly to enhance stability.[62] FEGs achieve much higher brightness, typically 10^8 to 10^9 A/cm² sr, enabling smaller probe sizes and better signal-to-noise ratios in demanding applications.[63] Their use is prevalent in advanced TEMs and SEMs for atomic-scale imaging.[58] A fundamental limitation of all electron sources is shot noise, arising from the Poisson statistics of electron emission, where the variance in electron count equals the mean number of electrons, leading to fluctuations that degrade image quality.[64] Additionally, the energy spread (ΔE) of the emitted electrons—typically 1–3 eV for thermionic guns and 0.3–0.7 eV for FEGs—contributes to chromatic aberration downstream, as electrons of varying energies focus differently.[65] This spread is narrower in FEGs due to the absence of thermal broadening, improving resolution in aberration-sensitive systems.[66] Electrons from the source are accelerated by voltages ranging from 1 kV in low-energy SEMs to 400 kV in high-voltage TEMs, with 100–300 kV often providing an optimal balance between achieving short de Broglie wavelengths for high resolution and minimizing beam-induced sample damage in sensitive materials.[67] Higher voltages reduce the relative impact of energy spread on aberrations but increase penetration and potential structural alteration in specimens.[68]Lenses and beam control

In electron microscopes, electromagnetic lenses serve as the primary optical elements for focusing and directing the electron beam, replacing glass lenses used in light microscopy due to the inability of materials to refract electrons effectively. These lenses operate on the principle of the Lorentz force, where a magnetic field generated by current-carrying coils deflects charged electrons toward the optical axis. Solenoid designs consist of helical windings around a soft iron core to produce a uniform axial magnetic field, while aperture designs incorporate pole pieces and a central aperture to shape the field more precisely, enhancing focusing power and reducing aberrations. The focal length of such a magnetic lens is approximated by where is the accelerating voltage, is the electron charge, is the magnetic field strength, is the bore radius, and is the electron rest mass; this relation highlights the lens's sensitivity to field strength and beam energy.[69] Condenser lenses, typically one or two in series above the sample, control beam convergence and illumination intensity by adjusting the current to vary their focal length, allowing the electron beam—emanating from the source—to be demagnified into a fine probe or diverged for parallel illumination in diffraction experiments. The objective lens, positioned closest to the sample, collects and focuses transmitted or scattered electrons to form the initial image, with its short focal length (often 1–5 mm) enabling high magnification up to 1 million times while determining key resolution limits through beam-sample interactions. Together, these lenses form a compound optical system that achieves sub-angstrom precision in modern instruments.[70] In scanning modes, such as those employed in scanning electron microscopes (SEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopes (STEM), scanning coils provide beam deflection via orthogonal magnetic fields, rastering the focused probe across the sample in a pixel-by-pixel pattern to build images sequentially. These coils enable scan speeds up to points per second, balancing acquisition time with signal quality for dynamic or large-area imaging. Alignment systems, including stigmators and deflectors, ensure beam symmetry; stigmators apply differential currents to correct astigmatism arising from lens imperfections, while deflectors fine-tune the beam path to center it on the optical axis, preventing off-axis aberrations and maintaining resolution.[71]Detectors and vacuum systems

In electron microscopes, detectors are crucial for capturing the various signals generated by electron-sample interactions, such as transmitted electrons in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and secondary electrons in scanning electron microscopy (SEM). For transmitted electrons, which pass through thin samples to form images based on beam intensity, detectors typically consist of a scintillator that converts electron energy into light, coupled to a photodiode or photomultiplier tube for signal amplification and detection.[72] This setup enables high-sensitivity imaging of internal sample structures by quantifying the transmitted beam's variations. In contrast, the Everhart-Thornley detector, widely used for secondary electrons—low-energy electrons emitted from the sample surface providing topographic information—employs a scintillator biased to attract and accelerate these electrons, followed by a photomultiplier tube for efficient signal collection. Electron microscopes require high vacuum environments to minimize electron scattering by residual gas molecules, ensuring a mean free path sufficient for the electron beam to reach the sample unaltered. Operating pressures typically range from ~1 Pa (or higher, up to ~1000 Pa) in low-vacuum or environmental scanning modes to 10^{-10} Pa in ultra-high vacuum transmission systems, with conventional high-vacuum SEM and TEM operating around 10^{-5} to 10^{-7} Pa.[73] To achieve these levels, turbomolecular pumps, which use high-speed rotating blades to transfer momentum to gas molecules, are employed for initial high-vacuum evacuation, often backed by rotary vane roughing pumps.[73] Ion pumps, utilizing strong electric fields to ionize and bury gas molecules into a titanium cathode, maintain ultra-high vacuums without moving parts, complementing turbomolecular systems in critical regions like the electron gun. Differential pumping is essential in electron microscopes to accommodate varying pressure requirements across components, preventing contamination while allowing sample introduction. This involves separate vacuum chambers connected by small apertures: the electron gun chamber is maintained at approximately 10^{-7} Pa to protect the source from outgassing, while the sample chamber in SEMs operates at around 10^{-5} Pa for standard imaging.[74] Turbomolecular and ion pumps are strategically placed in each stage to sustain these gradients, with the aperture limiting gas flow between compartments. For imaging hydrated or beam-sensitive samples, variable pressure SEM (VP-SEM) or environmental SEM (ESEM) adaptations introduce controlled gas pressures up to several hundred Pa in the sample chamber, using differential pumping to isolate the high-vacuum column.[75] This allows observation of wet biological specimens without dehydration, as water vapor neutralizes charging and maintains sample integrity during secondary electron imaging.[76]Imaging and analytical modes

Surface imaging modes

Surface imaging modes in scanning electron microscopy (SEM) primarily rely on electrons emitted from the sample surface following interaction with the incident electron beam. These modes utilize secondary electrons (SE) and backscattered electrons (BSE) to generate images that reveal surface topography and compositional variations, respectively. By scanning the focused beam across the sample and detecting these emitted signals, high-resolution surface details can be visualized without requiring transmission through the specimen.[77] Secondary electrons are low-energy electrons, typically with energies less than 50 eV, generated through inelastic scattering events where the incident beam excites and ejects electrons from the sample's outer atomic shells.[78] These SEs originate from a very shallow depth, with an escape depth of approximately 1-5 nm, making them highly sensitive to surface topography and providing excellent contrast for features like edges, roughness, and texture.[79] In SE imaging, the yield of detected electrons varies with local surface orientation relative to the detector, enhancing the three-dimensional appearance of the image.[77] Backscattered electrons, in contrast, are high-energy electrons (generally >50 eV, approaching the incident beam energy) produced by elastic scattering within the sample, where primary electrons are redirected back toward the surface.[80] BSEs emerge from a larger interaction volume, on the order of micrometers in depth and lateral extent, and their yield depends strongly on the atomic number (Z) of the elements present, resulting in Z-contrast imaging where heavier elements appear brighter due to higher backscattering efficiency.[81] This mode is particularly useful for distinguishing phases or inclusions in materials based on composition, though it offers less topographic detail than SE imaging.[77] The efficiency of SE and BSE emission is characterized by yield curves, which plot the secondary electron yield δ(E₀) and backscattered electron yield η(E₀) as functions of the incident beam energy E₀. The SE yield δ(E₀) typically rises from near zero at low E₀, peaks at a maximum (often around 200-1000 eV depending on the material), and then decreases asymptotically, reflecting the balance between electron generation and escape probability.[82] Similarly, the BSE yield η(E₀) increases monotonically with E₀ and atomic number, approaching values up to 0.5-0.6 for high-Z materials at keV energies, which informs optimal beam conditions for imaging.[81] These curves, derived from experimental measurements and Monte Carlo simulations, guide the selection of accelerating voltage to maximize signal while minimizing beam damage or charging.[83] For non-conductive samples, which can accumulate charge under the electron beam and distort images, variable pressure (or environmental) SEM modes introduce a low-pressure gas (typically 0.1-10 Torr of water vapor or nitrogen) into the specimen chamber to facilitate charge neutralization.[84] The incident electrons ionize the gas molecules, producing positive ions that are attracted to negatively charged regions on the sample surface, while free electrons from ionization can also contribute to balancing the charge; this gas-mediated process allows direct imaging of insulators like biological tissues or polymers without conductive coatings.[85] The presence of gas slightly scatters the primary beam and amplifies secondary signals through cascades, but it enables hydrated or wet sample observation under near-native conditions.[86]Transmission and diffraction modes

In transmission electron microscopy (TEM), transmitted electrons are utilized to reveal internal structures and crystallographic details of thin specimens. These modes exploit the interaction of the electron beam with the sample, where unscattered or minimally scattered electrons pass through, while diffracted electrons provide information on atomic arrangements. Key techniques include bright-field imaging, dark-field imaging, electron diffraction patterns, and phase contrast methods, each offering distinct contrast mechanisms for analyzing materials from metals to biomolecules.[87] Bright-field TEM imaging employs the direct, unscattered electron beam to form the image, with an objective aperture blocking scattered electrons to enhance contrast. In this mode, regions of the sample that transmit more electrons appear brighter, while areas with higher mass density or thickness scatter electrons more effectively, resulting in darker features due to mass-thickness contrast. This contrast arises because heavier atoms or thicker sections increase electron scattering probability, reducing the intensity of transmitted electrons reaching the detector. Bright-field mode is particularly effective for visualizing overall morphology and identifying dense inclusions in materials like alloys or biological tissues stained for enhanced scattering.[87][88] Dark-field TEM imaging, in contrast, selects diffracted electrons by centering a specific diffraction spot on the optic axis while blocking the direct beam, producing a dark background with bright features from scattering sites. This mode highlights crystal defects such as dislocations or stacking faults, as these regions bend the lattice and direct diffracted electrons into the aperture, increasing local intensity. It is also valuable for distinguishing crystallographic phases in polycrystalline samples by selectively imaging electrons from particular orientations. By emphasizing scattered electrons, dark-field reveals structural heterogeneities that may be obscured in bright-field views.[87][89] Electron diffraction modes provide crystallographic information by analyzing the angular distribution of transmitted electrons. In selected area electron diffraction (SAD), a small aperture selects a region (typically 0.5–5 μm) of the sample, and a parallel electron beam produces a spot pattern on the detector, where spot positions correspond to reciprocal lattice vectors. These patterns obey Bragg's law, given by where is an integer, is the electron wavelength, is the interplanar spacing, and is the diffraction angle; measuring allows determination of for phase identification and orientation mapping. Convergent beam electron diffraction (CBED) improves resolution by using a focused, convergent beam (probe size <50 nm) to generate disk-like patterns with internal symmetry, enabling point group determination and thickness measurement from higher-order Laue zones. CBED offers higher spatial precision than SAD for local structure analysis in nanomaterials.[89][90][91] Phase contrast modes enhance visibility of weakly scattering objects, such as unstained biomolecules, by converting phase shifts in the electron wave to amplitude differences. The defocus method achieves this by slightly underfocusing the objective lens, transferring low-spatial-frequency phase information into contrast, though it limits resolution due to spherical aberration at larger defocus values. The Zernike phase plate method inserts a thin-film plate (e.g., amorphous carbon, ~30 nm thick with a central hole) in the back focal plane to shift the phase of unscattered electrons by relative to scattered ones, providing uniform contrast at focus without resolution loss. This approach has enabled high-resolution imaging of proteins like GroEL at ~1.2 nm and viruses, improving signal-to-noise for cryo-TEM applications.[92][93]Spectroscopic analysis modes

Spectroscopic analysis modes in electron microscopy utilize the interactions between the electron beam and sample to extract chemical composition, electronic structure, and bonding information. These techniques rely on detecting emitted X-rays or energy losses from inelastic scattering events, enabling elemental identification and quantification at high spatial resolutions. In transmission electron microscopes (TEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopes (STEM), such modes complement imaging by providing analytical data from regions as small as a few nanometers. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), also known as EDX, detects X-rays generated when incident electrons interact with sample atoms, producing both a continuous bremsstrahlung spectrum from decelerated electrons and characteristic X-rays unique to each element's atomic structure. The bremsstrahlung background provides information on beam energy, while characteristic peaks allow elemental identification from beryllium to uranium, with detection limits around 0.1 wt% for most elements. Quantification in thin specimens, typically less than 100 nm thick, employs the Cliff-Lorimer method, which relates the ratio of characteristic X-ray intensities from two elements to their concentration ratio using experimentally determined k-factors, assuming negligible absorption and fluorescence effects. This approach, developed for STEM applications, achieves accuracies of 1-5% relative error for major elements in alloys and minerals.[94] Electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) measures the energy lost by transmitted electrons due to inelastic scattering, typically in the range of 10-1000 eV, revealing details about electronic excitations and core-level transitions. Low-loss EELS (<50 eV) probes plasmons and valence electrons, while core-loss EELS (>50 eV) identifies elements via ionization edges analogous to X-ray absorption. The fine structure near these edges, known as energy-loss near-edge structure (ELNES), encodes bonding and coordination information by reflecting the density of unoccupied states; for example, shifts in the silicon L-edge ELNES indicate Si-O versus Si-Si bonding environments. EELS offers superior energy resolution (0.1-1 eV) compared to EDS, enabling analysis of light elements like lithium and hydrogen, though it requires thinner samples (<50 nm) to minimize multiple scattering. Wavelength-dispersive spectroscopy (WDS) provides higher energy resolution (about 5-20 eV) than EDS (typically 130 eV), making it particularly effective for resolving overlapping peaks and quantifying light elements such as boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen in electron microprobes and TEM attachments. By diffracting X-rays with a curved crystal analyzer tuned to specific wavelengths via Bragg's law, WDS achieves lower detection limits (down to 10 ppm) and better peak-to-background ratios, though it requires sequential scanning and longer acquisition times. This mode is valuable for precise compositional analysis in geological and materials samples where EDS sensitivity to light elements is limited. In STEM, spectrum imaging combines raster scanning with EDS or EELS acquisition at each pixel to generate nanoscale elemental maps, achieving spatial resolutions of 1-5 nm for heavy elements and 5-10 nm for lighter ones. This technique produces hyperspectral datasets where elemental distributions are extracted via background subtraction and peak fitting, enabling visualization of segregation, precipitates, or diffusion profiles; for instance, in bimetallic nanoparticles, it reveals core-shell structures with atomic percent precision. Such mapping supports correlative studies of structure-property relationships in nanomaterials.[95]Advanced techniques and instruments

Aberration correction