Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Talapoin

View on Wikipedia

| Talapoins[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Subfamily: | Cercopithecinae |

| Tribe: | Cercopithecini |

| Genus: | Miopithecus I. Geoffroy, 1842 |

| Type species | |

| Simia talapoin Schreber, 1774

| |

| Species | |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

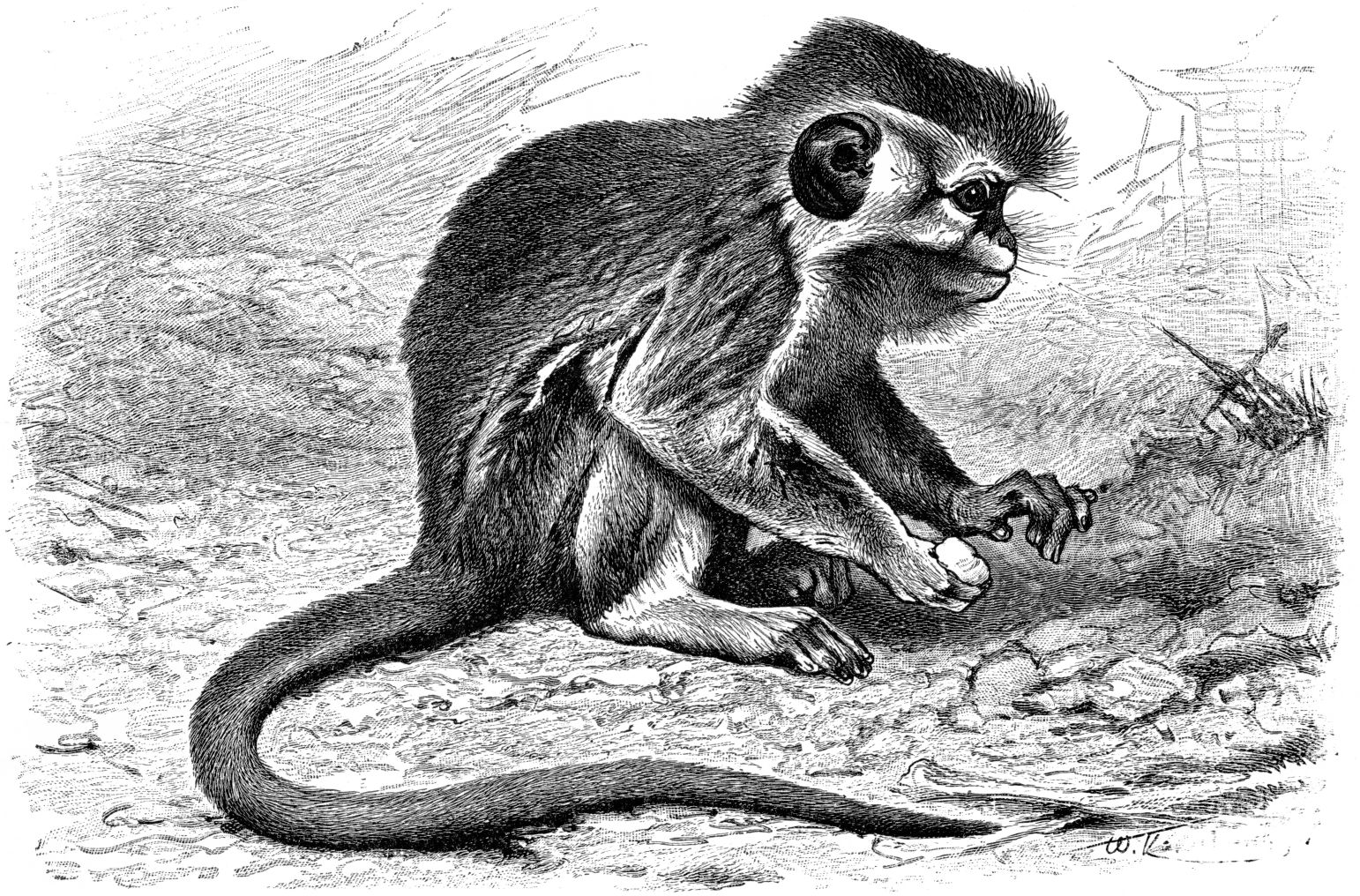

Talapoins (/ˈtæləpɔɪnz/) are the two species of Old World monkeys classified in genus Miopithecus. They live in central Africa, with their range extending from Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to Angola.

With a typical length of 32 to 45 centimetres (1 ft 1 in to 1 ft 6 in) and a weight of approximately 1.3 kilograms or 2.9 pounds (males) and 0.8 kilograms or 1.8 pounds (females), talapoins are the smallest Old World monkeys. Their fur is grey green on top and whitish on their underside, much like the vervet monkeys. The head is round and short-snouted with a hairless face.

Talapoins are diurnal and arboreal, preferring rain forest or mangroves near water. They are usually not found in open fields, nor do they seem to be disrupted by humans. Like Allen's swamp monkey, they can swim well and look in the water for food.

These monkeys live in groups of 60 to 100 individuals. They congregate at night in trees close to the water, dividing into smaller subgroups during the day to spread out to find food. Groups are composed of several fully mature males, numerous females and their offspring. Unlike the closely related guenons, they do not have any territorial behaviors. Their vocal repertoire is smaller, as well.

Talapoins are omnivores; their diet consists mainly of fruits, seeds, aquatic plants, insects, shellfish, bird eggs and small vertebrates.

Their 160-day gestation period (typically from November to March) results in the birth of a single young. Offspring are large, well developed — newborns weigh over 200 grams or 0.44 pounds or 7.1 ounces, which is about a quarter of the weight of the mother — and develop rapidly. Within six weeks, they eat solid food, and at three months of age, they are independent. The greatest recorded age of a talapoin in captivity was 28 years, while the life expectancy in the wild is not well known.

Species

[edit]| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angolan talapoin | M. talapoin (Schreber, 1774) |

Central Africa

|

Size: 32–45 cm (13–18 in) long, plus 36–53 cm (14–21 in) tail[2] Habitat: Forest and inland wetlands[3] Diet: Insects, leaves, seeds, fruit, water plants, grubs, eggs, and small vertebrates[2] |

VU

|

| Gabon talapoin | M. ogouensis Kingdon, 1997 |

Central Africa

|

Size: 23–36 cm (9–14 in) long, plus 31–45 cm (12–18 in) tail[4] Habitat: Forest[5] Diet: Fruit, seeds and insects[5] |

NT

|

Etymology

[edit]Talapoin is a 16th-century French word for a Buddhist monk, from Portuguese talapão, from Mon tala pōi "our lord"; originally jocular, from the appearance of the monkey.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). "GENUS Miopithecus". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Frederick, Bridget (2002). "Miopithecus talapoin". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Maisels, F.; Hart, J.; Ron, T.; Svensson, M.; Thompson, J. (2020) [amended version of 2019 assessment]. "Miopithecus talapoin". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020 e.T13572A166605916. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T13572A166605916.en.

- ^ Kingdon 2015, p. 145

- ^ a b c Maisels, F. (2019). "Miopithecus ogouensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019 e.T41570A17953573. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T41570A17953573.en.

- ^ "talapoin". Collins Concise English Dictionary © HarperCollins Publishers. WordReference.com. June 23, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

Sources

[edit]- Kingdon, Jonathan (2015). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (Second ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-2531-2.

External links

[edit]Talapoin

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Nomenclature

Classification

Talapoins belong to the order Primates, family Cercopithecidae (Old World monkeys), subfamily Cercopithecinae, tribe Cercopithecini, and genus Miopithecus.[2][7] As members of the Cercopithecidae, talapoins exhibit key Old World monkey traits that distinguish them from New World monkeys (family Cebidae), including non-prehensile tails that cannot grasp objects and the presence of cheek pouches for temporarily storing food.[8][9] These features reflect adaptations to terrestrial and arboreal lifestyles in African habitats, contrasting with the prehensile tails and lack of cheek pouches typical of New World species.[10] Phylogenetically, the genus Miopithecus is closely related to the guenons of genus Cercopithecus and other African cercopithecines, forming part of the diverse Cercopithecini tribe that arose during the Miocene epoch. Molecular studies using mitochondrial DNA and endogenous retroviruses confirm Miopithecus as a distinct lineage within this group, often described as "dwarf guenons" due to shared morphological and genetic similarities.[11] Historically, talapoins were classified as a subgenus of Cercopithecus based on superficial resemblances, but revisions in the late 20th century elevated Miopithecus to full genus status through comparative anatomy and phylogenetic analyses.[2][11] This separation was further supported by evidence of unique viral sequences and cellular markers distinguishing them from other guenons. The genus was initially considered monotypic until taxonomic studies in the late 1960s, including work by A. Machado in 1969, identified geographical variation warranting subspecies-level distinctions north and south of the Congo River; these were elevated to full species status in 1997.[2][12]Etymology

The term "talapoin" derives from the Portuguese "talapão," a word denoting a Buddhist monk or priest, which itself originates from the Mon language phrase "tala pōi," meaning "our lord." This nomenclature was adopted for the African primate in a humorous vein during the 16th century, reflecting early European perceptions of its diminutive stature and facial features.[13][14] The name entered scientific literature in the 18th century through descriptions of West African primates by European naturalists. Specifically, Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber provided the first formal scientific designation in 1774, naming the species Simia talapoin in his work on mammals, based on specimens from unknown localities in the region.[12] This usage persisted into the 19th century as naturalists like Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire further classified it within the genus Miopithecus in 1862.[15] Alternative common names include "dwarf guenon," where "guenon" stems from French, likely referring to the grimacing expression or trailing tail resembling ragged cloth (from "guenilles," meaning filthy rags). The genus name Miopithecus is derived briefly from Greek roots "mios" (small) and "pithekos" (ape), emphasizing its petite form.[16]Species

The genus Miopithecus includes two extant species of talapoins, both classified within the Old World monkey family Cercopithecidae.[5][6] The northern talapoin (Miopithecus ogouensis), also known as the Gabon talapoin, inhabits riparian and swamp forest habitats in southern Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the western Republic of the Congo, primarily centered around the Ogooué River basin.[5] Adults weigh 0.7–1.4 kg.[17] They exhibit minor morphological distinctions such as a shorter tail relative to body length.[18] The southern talapoin (Miopithecus talapoin), or Angolan talapoin, is distributed south of the Congo River in the southwestern Democratic Republic of the Congo and northern Angola, along rivers such as the Kasai, Cuanza, and Cuango.[6] It has adult males typically weighing 1.2–1.3 kg and females 0.75–0.82 kg, and shows subtle differences in facial pigmentation and pelage compared to the northern form.[6][18] These two species were recognized as distinct following a taxonomic revision in 1997 by Jonathan Kingdon, based on morphological variations including size, coat coloration, and geographic isolation by the Congo River; this split was further substantiated by genetic analyses of mitochondrial DNA and endogenous retroviruses in 2000, confirming significant divergence.[19][20] No extinct species are known within the genus Miopithecus, and its fossil record remains entirely absent, with the earliest related guenon fossils dating to the Pliocene epoch but not assignable to this lineage.[5][21]Physical Characteristics

Morphology

Talapoins (genus Miopithecus) are the smallest Old World monkeys, characterized by compact body proportions adapted for arboreal life.[3] Their average head-body length ranges from 32 to 45 cm, with tail lengths of 36 to 53 cm, exceeding the body length and aiding in balance during movement through dense vegetation.[2] Adults typically weigh between 0.8 and 1.9 kg, with sexual dimorphism resulting in males averaging around 1.3 kg at maturity and females closer to 0.8 kg.[2] Key anatomical features include a rounded head with a short snout and large eyes that enhance visual acuity in forested environments.[2] The tail is non-prehensile, covered in fur, and functions primarily for postural stability rather than grasping.[4] Like other Old World monkeys, talapoins possess opposable thumbs for precise manipulation of objects and ischial callosities—hardened skin pads on the buttocks that provide seating comfort during prolonged perching.[2] Skeletal proportions feature relatively short limbs relative to body size, facilitating agile quadrupedal locomotion and leaping in the canopy.[22] Ontogenetic studies reveal correlated allometry in these proportions, arising from reduced growth rates that result in a miniaturized form compared to larger cercopithecids, without independent heterochronic shifts in specific segments.[22]Coloration and Adaptations

Talapoins display a pelage adapted for concealment in dense, humid forest understories, with fur that is typically grey-green or greenish-yellow dorsally, speckled with gray, transitioning to whitish or pale yellow ventrally. This dorsal-ventral contrast enhances crypsis against predators by matching the mottled light and shadow of their arboreal and terrestrial environments. Around the eyes, golden or yellow fur forms distinctive patches, while a light-colored "bib" of whitish hair extends across the chest, blending seamlessly with the ventral fur. Limbs are paler, often chrome yellow with a buff or reddish tint, and the tail is darker gray-black above with yellowish undertones.[3][2][4] The bare facial skin of talapoins is hairless and prominently featured, with dark blackish bordering around the nose and ears, creating a masked appearance that contrasts with surrounding yellow whiskers and framing hair. In the Angolan talapoin (Miopithecus talapoin), this facial skin is blackish, while in the Gabon talapoin (M. ogouensis), it tends toward flesh-colored. These skin features, combined with the naked muzzle, facilitate visual communication in low-light conditions typical of their habitats. Sexual dimorphism in coloration is minimal but present; males generally exhibit more vibrant hues overall, with females appearing paler, though no pronounced seasonal changes in eye ring brightness have been documented.[3][2] Physiological adaptations in talapoins support their opportunistic foraging lifestyle in tropical environments. Prominent cheek pouches allow temporary storage of fruits, seeds, and insects, enabling efficient collection during brief foraging bouts amid predation risks. Like other cercopithecines, talapoins possess eccrine sweat glands distributed across the body, aiding thermoregulation through evaporative cooling in the hot, humid conditions of their range, where behavioral options like shade-seeking may be limited.[2][23]Distribution and Habitat

Geographic Range

Talapoins inhabit riparian zones and forested areas across Central Africa, with their overall range spanning from Cameroon in the north to Angola in the south and centered on the Congo River basin. Following the taxonomic split in 2019, the genus comprises two distinct species with separate ranges.[5][6] The northern talapoin (Miopithecus ogouensis) is restricted to coastal and near-coastal regions, including southern Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the western Republic of the Congo, where populations are closely tied to river systems such as the Ogooué River.[5][19] In contrast, the southern talapoin (Miopithecus talapoin) occupies more inland distributions along the Congo River and its tributaries, extending through the Democratic Republic of the Congo and northern Angola, with an estimated extent of occurrence covering approximately 400,000 km² (as of 2018).[24] Populations of both species are suspected to be declining due to habitat loss from deforestation, potentially leading to range contractions.[5][6]Habitat Preferences

Talapoins, comprising the northern talapoin (Miopithecus ogouensis) and southern talapoin (M. talapoin), primarily inhabit swamp forests, mangroves, riverine forests, and flooded woodlands within lowland equatorial regions of central Africa.[2][5] These environments provide dense, moist vegetation essential for their survival, with the species strictly associated with riparian zones where water bodies facilitate escape from predators via swimming and diving.[4][25] Their altitudinal range extends from sea level to approximately 700 meters, though they predominantly occupy low-elevation areas below 500 meters with closed-canopy forests, favoring sites with proximity to permanent or seasonal water sources.[24] Within these habitats, talapoins utilize microhabitats in the lower canopy layers for arboreal locomotion and resting, often sleeping in trees overhanging water to deter terrestrial predators.[2][26] They supplement this with ground-level foraging, particularly for seeds and invertebrates, which becomes more prominent in drier periods when understory access improves.[3][27] Seasonal variations influence their habitat use, as talapoins rely on evergreen riparian vegetation to maintain year-round resources amid fluctuating water levels in flooded woodlands. During periods of inundation, they remain in these swampy areas, leveraging their swimming abilities to navigate flooded zones, while drier seasons allow expanded ground activity without significant relocation.[2][25] This adaptability to seasonal flooding underscores their specialization in wetland ecosystems, where dense cover and water access are consistent features.[28]Behavior and Ecology

Social Structure

Talapoin monkeys (Miopithecus talapoin) live in large, cohesive troops typically numbering 70 to 100 individuals, exhibiting a multi-male, multi-female social structure that allows for flexible subgrouping during daily activities.[29] These troops divide into smaller units for foraging and movement, commonly consisting of all-male groups of adults and large juveniles, female-centered subgroups with infants and smaller juveniles, and mixed juvenile parties often led by a single adult male.[29] Outside the breeding season, adult males and females maintain spatial separation within the troop, with minimal direct interactions observed between the sexes, though subgroups may coalesce for synchronized travel across their home range.[30] The social hierarchy in talapoin societies is characterized by female philopatry, where females remain in their natal groups and form stable matrilineal kin networks that serve as the core of the troop's stability.[31] In contrast, males disperse from their birth groups upon reaching maturity, which contributes to relatively loose and fluid dominance relations among adult males, lacking the rigid linear hierarchies seen in many other Old World monkeys.[31] Female dominance over males is common, even though males are larger, and aggression is typically low outside of resource competition or breeding contexts, with grooming serving as a primary mechanism for maintaining alliances and reducing tension within kin groups.[32] Communication among talapoins relies on a combination of vocalizations, visual signals, and tactile behaviors to coordinate group activities and social bonds. Vocal repertoire includes chirps for cohesion and alert calls during threats, as well as screams in aggressive encounters, enabling rapid information sharing across subgroups. Facial expressions, often involving the bare skin around the eyes and anogenital region, convey submission or tension, such as through lip-smacking or "grin faces," while grooming facilitates bonding, particularly among females and their kin, and occurs in synchronized bouts during rest periods.[32] Talapoins are strictly diurnal, with daily activities centered on synchronized group travel for foraging, covering approximately 3 km within their home range, followed by evening congregation in tree clusters for sleeping.[29] This pattern enhances predator vigilance and resource access, with subgroups merging at night to form a unified sleeping party high in the canopy.[29]Diet and Foraging

Talapoins (genus Miopithecus) are omnivorous primates with a diet dominated by fruits, which constitute approximately 52% of their intake on average, though this can range from 0% to 90% depending on availability.[33] This frugivorous emphasis is supplemented by significant animal matter, including insects and other prey items that make up about 35% (ranging 0–50%), as well as leaves and shoots (5%, 0–22%), flowers (2%), stems, pith, or bark (4%, 0–10%), and grasses or crops (8%, 0–80%).[33] Aquatic plants, seeds, grubs, bird eggs, small vertebrates, and shellfish also feature regularly, reflecting their proximity to riverine habitats where such resources are accessible.[2] Near human settlements, talapoins opportunistically raid crops like manioc roots, increasing the proportion of tubers and roots in their diet when wild fruits are scarce.[2] Foraging occurs primarily during diurnal hours, with peaks in the early morning and late afternoon, and employs a mix of arboreal and terrestrial techniques adapted to swampy, forested environments. Individuals pick fruits and leaves from low understory vegetation or tree branches, while ground-level scavenging targets insects, aquatic plants, and roots near water edges; they are known to swim short distances to access food.[3] A key adaptation is the use of expandable cheek pouches to store and transport food items like seeds and insects, allowing efficient collection without immediate consumption and reducing time exposed to predators during feeding.[2] In the case of the Gabon talapoin (M. ogouensis), foraging includes active hunting of arthropods such as beetles, caterpillars, ants, and spiders in the undergrowth, as well as digging for roots like African ginger.[4] Dietary composition exhibits seasonal shifts tied to resource availability in their tropical habitats, with fruit intake peaking during wet seasons when abundance is high and dropping to near zero in dry periods, prompting reliance on insects, leaves, and fallback foods like pith, snails, or tubers.[33] For instance, animal prey such as orthopterans and shrimp may increase to one-third or more of the diet during fruit shortages, providing essential protein.[4] Group foraging in large troops (60–120 individuals) involves splitting into smaller, same-sex or mixed subgroups for coordinated travel to fruiting trees or insect-rich areas, minimizing competition and predation risk; vocalizations like "mew" calls help maintain contact and share information on food locations.[3] Juveniles learn these strategies by observing and following adults, enhancing group efficiency in exploiting patchy resources.[4]Reproduction and Life Cycle

Talapoins exhibit a promiscuous mating system within their multimale-multifemale troops, where females in estrus solicit copulations from multiple males, and breeding peaks during the dry season from May to September.[2] Gestation lasts 158 to 166 days.[2][18] Births typically occur from November to March, yielding a single precocial offspring, with twins being rare.[2] Newborns weigh approximately 180 grams (range 170–230 grams) and are initially carried ventrally by the mother, shifting to dorsal carriage as the infant develops mobility around two weeks of age.[34][2] Infants begin consuming solid food at about six weeks and are weaned at 3 to 4 months, achieving independence shortly thereafter.[2][35] Females reach sexual maturity at 3 to 4 years, while males do so at 4 to 5 years.[36][34] In the wild, lifespan is not precisely documented but is likely shorter than the up to 28 years observed in captivity, with estimates around 15 to 20 years based on comparative primate data.[2][37] Mothers provide primary parental care, including protection and provisioning, supplemented by allomothering from other group females, which helps mitigate risks in the social troop.[3] Infant mortality is high, largely due to predation by raptors, snakes, and mammals such as leopards.[38]Conservation

Threats

Talapoins, primarily inhabiting riverine and swamp forests in the Congo Basin, face severe habitat loss driven by deforestation for agriculture and commercial logging. In Angola, where the southern talapoin (Miopithecus talapoin) occurs, forest cover loss has accelerated rapidly, with approximately 2.4% of tree cover in its range disappearing between 2001 and 2016; this figure likely underestimates impacts on the species' narrow riparian habitats, which are particularly vulnerable to fragmentation.[39] Across the broader Congo Basin, intact forest cover declined from 78% to 67% between 2000 and 2016, affecting up to 23 million hectares and encroaching on talapoin habitats through expanding small-scale agriculture and timber extraction.[40] For instance, Quiçama National Park in Angola, a key site for the southern talapoin, lost 160 km² of forest since 2001.[39] Hunting poses a direct mortality threat, with talapoins targeted in the bushmeat trade for local consumption and sale, especially in rural communities of Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In Angola, southern talapoins appear at roadside bushmeat stalls and are hunted within protected areas like Quiçama National Park.[39] In the DRC, they are often caught incidentally in snares set for larger species but consumed regardless, exacerbating pressure on populations already stressed by habitat degradation.[39] The northern talapoin (Miopithecus ogouensis) faces similar small-scale hunting, though its smaller body size historically reduced targeting.[17] Additional threats include disease transmission from humans, heightened by bushmeat handling and habitat overlap, and climate-induced alterations to swampy environments. Climate change exacerbates risks via shifting weather patterns, including prolonged dry seasons and altered flooding regimes that disrupt seasonally flooded forests and mangroves essential for talapoin foraging and refuge.[39] These pressures have led to substantial population declines, with the southern talapoin estimated to have decreased by more than 30% over three generations (24 years, from 2005 to 2029) due to combined habitat loss and hunting.[39] The northern talapoin shows a continuing decline in mature individuals, classified as Near Threatened, while the overall genus faces range contraction in the Congo Basin's dynamic ecosystems.[17]Status and Protection

The northern talapoin (Miopithecus ogouensis) is classified as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List, with an assessment conducted in 2017 indicating a decreasing population trend due to ongoing habitat loss and hunting pressures. In contrast, the southern talapoin (Miopithecus talapoin) is listed as Vulnerable under the same framework, upgraded from Least Concern in 2020 based on evidence of substantial population declines exceeding 30% over three generations from habitat degradation and bushmeat trade. These classifications highlight the differing conservation priorities for the two species, with the southern talapoin facing more acute risks across its range in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola. Both talapoin species are protected under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which regulates international trade to prevent overexploitation while allowing sustainable commerce. Key protected areas support their conservation: the northern talapoin occurs in Lopé National Park in Gabon, a UNESCO World Heritage site where park management focuses on habitat preservation amid riparian forests. The southern talapoin is found within Salonga National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the largest tropical rainforest protected area in Africa, encompassing over 36,000 square kilometers of swamp and lowland forest essential for the species. Conservation initiatives emphasize habitat restoration and anti-poaching measures in these protected areas. Since 2010, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) has partnered with the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN) in Salonga National Park to enhance patrols, reduce illegal logging and poaching, and restore degraded swamp forests through community-based programs that promote sustainable livelihoods for local populations. Similarly, IUCN supports broader primate conservation in Central Africa, including monitoring and capacity-building efforts in Gabon's protected areas like Lopé to address threats such as agricultural expansion. These efforts have improved enforcement in select regions, though challenges persist due to limited funding and political instability. Despite these protections, significant research gaps remain, particularly the need for comprehensive population surveys post-2025 to update outdated data from the 2010s and assess the impact of climate change on riparian habitats. The future outlook for talapoins depends on strengthened transboundary cooperation and increased funding for anti-poaching, as ongoing threats like deforestation continue to drive local declines despite their protected status.References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Miopithecus